Abstract

Recent randomised trials on screening with low-dose CT have shown important reductions in lung cancer (LC) mortality and have triggered international efforts to implement LC screening. Detection rates of stage I LC with volume CT approaching 70% have been demonstrated. In April 2019 ‘ESMO Open – Cancer Horizons’ convened a roundtable discussion on the challenges and potential solutions regarding the implementation of LC screening in Europe. The expert panel reviewed the current evidence for LC screening with low-dose CT and discussed the next steps, which are covered in this article. The panel concluded that national health policy groups in Europe should start to implement CT screening as adequate evidence is available. It was recognised that there are opportunities to improve the screening process through ‘Implementation Research Programmes’.

Keywords: Lung cancer screening, patient recruitment, nodule management, lung cancer mortality, secondary care pathways

Video Abstract.

Introduction

Recent large randomised trials on low-dose CT screening, including the American National Cancer Institute-sponsored National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) as well as the Dutch/Belgian NELSON (Nederlands-Leuvens Longkanker Screenings Onderzoek) trial, have shown significant reductions in lung cancer (LC) mortality of 20%–26% and have triggered international efforts to implement LC screening.1–3 As demonstrated by the results from the International Early Lung Cancer Action Project (I-ELCAP) and the NELSON clinical trials groups, detection rates of stage I LC with volume CT could approach 70%.

In April 2019 ‘ESMO Open – Cancer Horizons’ convened a roundtable discussion on the challenges and potential solutions regarding the implementation of LC screening in Europe. The expert panel reviewed the current evidence for LC screening with low-dose CT and discussed the next steps, which are covered in this article.

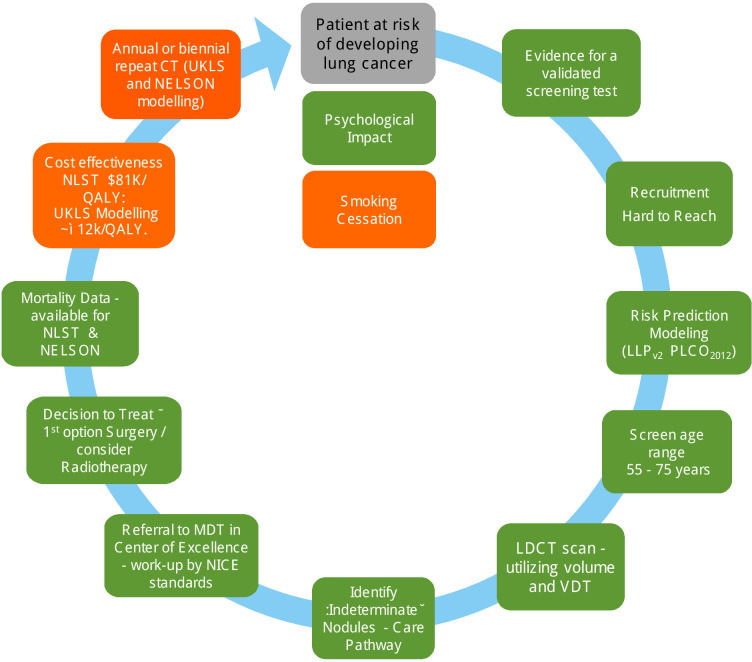

Figure 1 shows levels of evidence for implementation of LC screening in Europe.

Figure 1.

Levels of evidence for implementation of lung cancer screening in Europe.4 Amended/updated in 2019 from a figure published in ref 4 in 2016. Colour codes: green: sufficient evidence; amber: borderline evidence. LDCT, low-dose CT; LLP, Liverpool Lung Project; MDT, multidisciplinary team; NELSON, Nederlands-Leuvens Longkanker Screenings Onderzoek; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NLST, National Lung Screening Trial; PLCO, Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; UKLS, UK Lung Cancer Screening Trial; VDT, volume doubling time.

Recruitment for national LC screening programmes

The aim regarding recruitment for national LC screening programmes is to achieve an informed participation focusing on high-risk (hard-to-reach) individuals. Those at highest risk of LC are those who are most likely to benefit from screening (even when considering comorbidity); however, they are less likely to participate in LC screening and are more likely to be of lower socioeconomic background and to be current smokers.4

Recruitment challenges

Screening approaches

It is a difficult balance between the availability of systematic risk data of a relatively large group of approachable individuals (health registers, primary care registers, questionnaires, online surveys) and ensuring equity, versus the less systematic and less costly approaches for smaller groups, which are likely to be the worried well (through clinics and advertising).

Age

It has been argued whether to start recruitment at age 60 or 55. Screening strategies for Switzerland indicate a starting age of 60 and include those up to 79 years of age. The National Health Service (NHS) England Protocol,5 however, argues for screening between 55 and 75 years of age. A number of risk prediction models have been developed, of which the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO)20126 (1.6% risk over 6 years) and the Liverpool Lung Project (LLP)v27 8 (2.5% risk over 5 years) have both been included in the recent NHS England Protocol.

In the USA, the US Preventive Services Task Force9 on LC screening has a much less stringent selection criteria, which is based on the NLST and the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network.10

Smoking

Some consider one basic inclusion question would suffice: ‘have you ever smoked?’

Information technology

Investment into information technology systems is needed to collate patients’ risk data and also to manage and monitor LC CT-screened patients. In the UK this has recently been amplified by Sir Professor Richards’ interim report on UK cancer screening.11

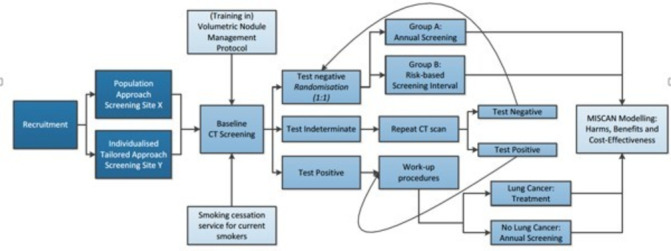

Role-out of LC screening in Europe

The roundtable panel recognised that LC screening can be initiated in Europe; however, there is room for improvement in several areas, and the recommendation discussed is provided in figure 2.

Figure 2.

European implementation trials needed (source: Harry de Koning (PI) Erasmus MC. Towards individually tailored invitations, screenings intervals, and integrated co-morbidity reducing strategies in lung cancer screening (acronym: 4-IN-THE-LUNG-RUN). European Research Council; H2020-SC1-BHC-2018-2020; grant848294; 2019.)

LC screening

Radiology protocol

The most recent European protocol for the management of CT-detected nodules was published in Lancet Oncology in 2017,3 which was developed as a consensus document by experts from nine countries within Europe. Using volume doubling time (VDT) biomarker reduces invasive procedures, biopsies and surgery by tenfold12 compared with the NLST data.1

Recently, it has been recognised that new nodules are common in follow-up CT scans (3%–13% screenings)13 14 and comprise a significantly higher LC probability, which are at smaller size, thus the recommendation for new nodules during the screening process.

These more stringent cut-off values should be mandatory:

Negative screen result: <30 mm3 (LC probability <1%).

Indeterminate screen result: 30–200 mm3 (LC probability ~3%).

Positive screen result: >200 mm3 (LC probability ~17%).

Screening interval

The screening interval, annual versus biennial, has been debated in the literature.15–17 Clearly the optimal screen intervals should consider using the previous CT screen results to estimate LC risk. However, in the light of the recent NELSON results given at the World Conference on Lung Cancer (WCLC) in 2018,2 the annual screening frequency is considered the default until more data supporting other approaches may be available. Nevertheless, it is recognised that there is a potential avenue to select individuals with a low risk of developing LC using their baseline scan, and depending on their overall risk profile they could be considered for biennial screening.18–20 This would need continued monitoring during the screening lifetime of the patient.

Quality assurance

Quality assurance (QA) in CT screening has been poorly implemented. Therefore, the prospect of setting up LC CT screening imaging core laboratories for QA as well as benchmarking the automated CT scan software and postprocessing procedures are attractive options. However mature, validated tools for these purposes are not yet widely available. In the mean time, there is a preference for the delivery of LC screening care in dedicated clinical centres of excellence and using virtual central reading of the CT scans.

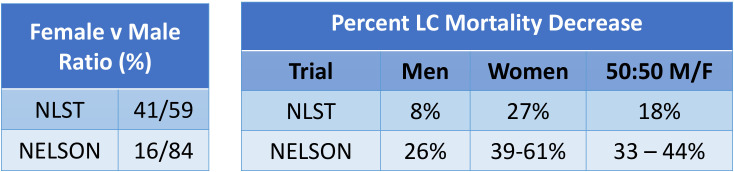

Mortality reduction in women

The NELSON presentation at the WCLC in 20182 provides evidence for LC mortality reduction in women (39%–61%).2 21 In the NLST this figure was 27% for women (figure 3). The implication for the higher mortality gain in women compared with men is poorly understood and requires further investigation.

Figure 3.

LC CT screening: NLST and Nelson mortality data presented at WCLC 2018.2 Source: Data provided by de Koning at WCLC 2018.2 21 F, female; LC, lung cancer; M, male; NELSON, Nederlands-Leuvens Longkanker Screenings Onderzoek; NLST, National Lung Screening Trial; WCLC, World Conference on Lung Cancer.

Prolonged low-dose CT screening

The Multicentric Italian Lung Detection (MILD) trial recently evaluated the benefit of prolonged low-dose CT screening beyond 5 years, and its impact on overall and LC-specific mortality at 10 years.22 MILD prospectively randomised 4099 participants, to a screening arm (n ¼ 2376), with further randomisation to annual (n ¼ 1190) or biennial (n ¼ 1186) low-dose CT for a median period of 6 years, or a control arm (n ¼ 1723) without intervention.

In the MILD trial, 2005 and 2018 and 39 293 person-years of follow-up were accumulated. The primary outcomes were 10-year overall and LC-specific mortality. The low-dose CT arm showed a 39% reduced risk of LC mortality at 10 years (HR 0.61; 95% CI 0.39 to 0.95), compared with control arm, and a 20% reduction of overall mortality (HR 0.80; 95% CI 0.62 to 1.03). The MILD trial provides further evidence that prolonged screening beyond 5 years can enhance the benefit of early detection and achieve a greater overall and LC mortality reduction compared with NLST trial.

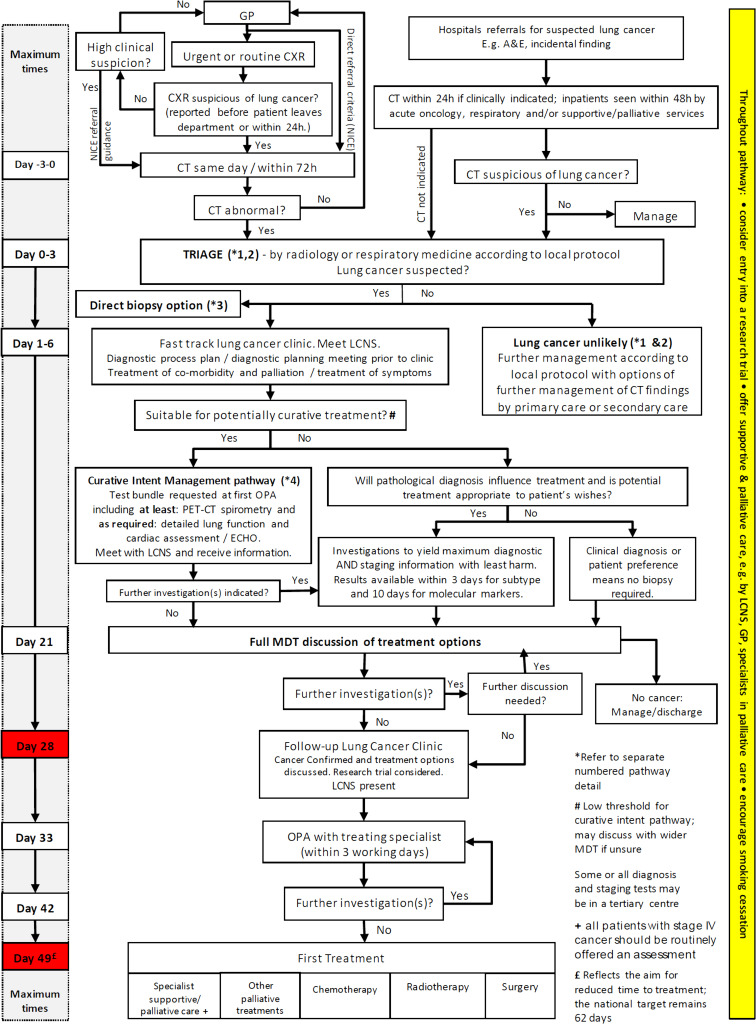

Secondary care pathways: UK protocols to assist the implementation of LC screening

The UK National Optimal Lung Cancer Pathway (NOLCP) is a timed secondary care pathway approved by NHS England (figure 4).

Figure 4.

National Optimal Lung Cancer Pathway for suspected and confirmed LC: referral to treatment 2017 V.2 update produced by the Clinical Expert Group for Lung Cancer; NHSE, National Health Service England; CXR, chest X-ray; GP, general practitioner; LC, lung cancer; MDT, multidisciplinary team; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; PET, positron emission tomography.

Key features of the early part of the NOLCP include recommendations for rapid access to a CT of the thorax (within 72 hours of referral or chest radiograph) and a subsequent triage process. The latter stratifies patients with suspicious CT findings into fast-track cancer clinics, with subsequent rapid investigations for and management of LC, or appropriately diverts others from cancer pathways into alternative services. This includes the management of pulmonary nodules according to the British Thoracic Society guideline.23

The integration of the NOLCP with CT screening provides an opportunity to transform care, as it maximises the benefits of each and ensures that optimal care is provided to patients throughout their clinical pathway. The current UK cancer waiting times and unwarranted variations in care reflect systemic problems in organisational process and capacity. Thus, this must be driven nationally with regional and local coordination of funding and services.

Multidisciplinary clinics: planning for long-term treatment of CT-screened patients with LC

It is important that medical oncologists are part of the long-term treatment planning of CT-screened patients with a diagnosis of LC; the same is true for radiologists, pulmonologists, surgeons, nuclear medicine physicians and cancer nurses. A critical member of the team is the smoking cessation counsellor, as the enhanced feedback associated with annual attention to smoking cessation seems to enhance quit rates. The cost of medical care in older smokers can be significantly reduced (by about one-third) by inclusion of best practice smoking cessation advice24–26 and greatly enhance the cost utility of this integrated screening service.

Large-scale implementation of LC screening within nationwide screening programmes in Europe will significantly change the landscape of treatment strategies for patients due to earlier diagnosis. Hopefully, fewer patients with advanced stages will need more palliative approaches with systemic treatment (chemotherapy, chemoimmunotherapy, immunotherapy), but more patients may need adjuvant and consolidation systemic treatments (stages II and III, chemotherapy, immunotherapy). Furthermore, conversations should also be starting on how to use best practice guidelines to manage the large number of asymptomatic screening subjects who will be found to have objective evidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or advanced coronary calcifications. Important trials in the Netherlands25 and China are already exploring this critical new avenue of public health investigation.

Medical oncologists may also need to shift their interest from the approaches to advanced disease to ‘multidisciplinary approaches’ of stages II, IIIA, IIIB and IVA of LC. Further clinical trials with systemic treatments for very early LC stages (immunotherapy, chemoimmunotherapy, targeted therapy) can be foreseen. As new cancer precursors are detected within the screening population, a new generation of chemoprevention trials can be expected. This could potentially include immunological manipulation of the early cancer development process.

LC biomarkers in early LC detection

The ‘holy grail’ in biomarker research is to identify other early detection biomarker(s) beyond the above-discussed imaging biomarkers. Despite a massive investment of resources, non-imaging biomarkers have had limited success. A recent systematic review on serum and blood-based biomarkers for LC screening provided an excellent update of this topic.27 It evaluated the diagnostic performance of EarlyCDT-Lung (an antibody-based biomarker screening panel), microRNA (miRNA) signature classifier (a plasma-based 24 miRNA risk score) and miR-test (a serum-based 13 miRNA signature), and their impact on LC-related mortality and all-cause mortality. Three phase III studies were identified, and all three biomarker assays show promise for the detection of LC. However, there was a lack of definitive evidence to justify integration into clinical practice.

Seijo and colleagues28 have recently proposed a number of principles to optimise LC biomarker discovery projects. They provided an overview of promising molecular candidates, such as autoantibodies, complement fragments, miRNAs, circulating tumour DNA, DNA methylation, blood protein profiling, and RNA airway or nasal signatures. The emerging biomarkers include exhaled breath biomarkers, metabolomics, sputum cell imaging, genetic predisposition studies and the integration of next-generation sequencing into the study of circulating DNA. All of these need to be considered in the scope of future implementation research in LC screening, together with imaging, radiomics and artificial intelligence.29

Recent innovative research programmes: which can impact on future LC screening implementation research?

Early Lung Imaging Confederation

Since the global implementation of LC screening is only starting just now, there has not been the time nor the resources so far to create specialised imaging tools to enable easy and rapid LC screening management. The Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance organised by the Radiological Society of North America has been working to define scalable solutions to ensure robust and accurate use of volumetric CT imaging to guide screening work-up,30 as already published in the UK Lung Cancer Screening Trial (UKLS)8 and NELSON trial.3 Large collections of thoracic CT images with known clinical outcomes are urgently needed to develop and validate LC imaging management tools.31

The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) is committed to developing a large collection of thoracic CT images to address this bottleneck.32 The IASLC with a large multidisciplinary team has begun to develop the Early Lung Imaging Confederation (ELIC). The goal is to make this cloud-based image collection/research resource accessible to all IASLC investigators as well as others, as an open resource to accelerate the development of imaging and other tools to manage early LC.

Institute for Diagnostic Accuracy Management System

The Institute for Diagnostic Accuracy (iDNA) Management System has been developed from the NELSON and UKLS screening trial databases.8 12 It is a highly configurable client tracking system where clients are screening participants (or patients) and where all types of events are stored in the client’s history. This client history contains all relevant details needed for logistical and data management, including features specifically designed for LC screening purposes, such as nodule evaluation across multiple evaluations and across multiple scan moments. This allows central review of CT scans, automated calculations on VDTs and automated classification of screening results (based on the optimised NELSON protocol). Second, the software is designed to support clear and secure communication between the screening site and the screening participants on undertaking LC risk assessment (LLPv2 and PLCO2012), making appointments, completion of questionnaires (eg, on smoking history and informed consent), reporting on screening results, integration with email and the use of configurable templates for standard notifications and letters. With the iDNA Management System all the screening sites’ specific needs on data collection, logistics and communication can be configured by local administrators, ensuring full compliance with local requirements.

Collection of radiological metadata is organised in multiple steps and levels, which is based on a direct link between the radiologist’s workstation and the iDNA Management System: a screening participant can have more than one CT scan record; one CT scan record can have multiple readings/observations; and one observation can have multiple nodules and other findings.

The primary application of the iDNA Management System is the registration and management of nodules in LC screening programmes. The iDNA system has been extended with registration and management of calcium scores (for cardiovascular diseases),30 33 which can be used by collaborative screening sites.34 Other radiological features include the validated import of XML (eXtensible Markup Language) files generated by local workstations directly into the study database.

Other comparable systems are being developed, including a collaborative effort between the Veterans Administration in the USA working with the I-ELCAP with support from the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation using an open-source software environment.

General Data Protection Regulation

The recommendation of a European registry for collection of LC CT screening data was discussed at the round table and that the IASLC is exploring options in this regard.32 Ideally a registry for screened LC CT images should be developed. However, the changing laws around the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) are making this more difficult as it is practically impossible to anonymise CT Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine images. This is a challenge not just within the LC community; it impacts on all radiological imaging and needs to be resolved within the European Parliament. It would be tragic if reasonable measures to ensure personal data protections were to unintentionally delay or even block progress in improving curative outcomes for Europe’s most lethal adult cancer.

Conclusion

The conclusion reached by the roundtable panel was that national health policy groups in Europe should start to implement CT screening now as adequate evidence is available (figure 1).4 It was recognised that there are opportunities to improve the ‘screening process’ through ‘Implementation Research Programmes’. Areas which need specific consideration are around cost-effectiveness (UKLS data indicate £12 000/quality-adjusted life year) and if biennial screening is appropriate for a subset of individuals with appropriately delivered integrated smoking cessation programmes in place.

Overall recommendations

Implementation of LC screening should be a priority in Europe. It needs to be driven scientifically, politically and also using patient advocacy.

Europe needs to plan ‘Implementation Research Programmes’.

Investment is needed into recruitment challenges especially in ‘hard to reach’ communities.

Ensure thoracic radiologists reporting on CT-screened individuals use volume and VDT and are provided with the necessary training and work, with QA procedures in place.

The issues around current GDPR need to be resolved, in order to enable the development of a European registry for collection of LC CT screening data.

Secondary care pathways are aligned with the imminent implementation of LC screening, together with service provision and availability of screening platforms.

Develop a collegiate approach to the work-up and treatment of patients with LC in multidisciplinary clinics, identified through CT screening programmes. All clinical specialties should be fully engaged, including medical oncologists.

The role of non-imaging early detection biomarkers is still in an early phase; however, the LC screening community should be fully engaged and participate in the developing integrated research programmes using molecular/radiomics and artificial intelligence approaches.

Innovative research programmes (eg, ELIC and iDNA) provide enormous potential which can impact on LC screening and save lives.

LC CT screening will happen in Europe. It is up to the community to make it happen now.

Acknowledgments

Dr Christiane Rehwagen has organised the round table and provided medical writing support.

Footnotes

Contributors: The manuscript was drafted by JKF and reviewed by all authors.

Funding: This initiative is sponsored by AstraZeneca through the provision of an unrestricted educational grant to BMJ. AstraZeneca has had no influence over the content other than a review of the paper for medical accuracy. The participants/authors received an honorarium and travel expenses for their participation in the round table from BMJ.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:395–409. 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koning DB, van Aalst CM, Ten Haaf K. Effects of volumetric CT lung cancer screening: mortality results of the Nelson randomised-controlled population based trial WCLC2018. Toronto: IASLC, 2018: 2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oudkerk M, Devaraj A, Vliegenthart R, et al. . European position statement on lung cancer screening. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:e754–66. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30861-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghimire B, Maroni R, Vulkan D, et al. . Evaluation of a health service adopting proactive approach to reduce high risk of lung cancer: the Liverpool healthy lung programme. Lung Cancer 2019;134:66–71. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NHS-Eng-National-Cancer-Programme Targeted screening for lung cancer with low radiation dose computed tomography; standard protocol prepared for the targeted lung health checks programme, 2019. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/targeted-lung-health-checks-standard-protocol-v1.pdf [Accessed 16 Apr 2019].

- 6.Tammemagi CM, Pinsky PF, Caporaso NE, et al. . Lung cancer risk prediction: prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian cancer screening trial models and validation. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1058–68. 10.1093/jnci/djr173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassidy A, Myles JP, van Tongeren M, et al. . The LLP risk model: an individual risk prediction model for lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2008;98:270–6. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field JK, Duffy SW, Baldwin DR, et al. . The UK lung cancer screening trial: a pilot randomised controlled trial of low-dose computed tomography screening for the early detection of lung cancer. Health Technol Assess 2016;20:1–146. 10.3310/hta20400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.USPSTF Uspstf lung cancer screening 2015, 2015. Available: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/lung-cancer-screening [Accessed 29 May 2018].

- 10.de Koning HJ, Meza R, Plevritis SK, et al. . Benefits and harms of computed tomography lung cancer screening strategies: a comparative modeling study for the U.S. preventive services Task force. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:311–20. 10.7326/M13-2316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards M. Independent review of national cancer screening programmes in England: interim report of emerging findings, 2019. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/independent-review-of-cancer-screening-programmes-interim-report.pdf [Accessed 04 Jun 2019].

- 12.van Klaveren RJ, Oudkerk M, Prokop M, et al. . Management of lung nodules detected by volume CT scanning. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2221–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa0906085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heuvelmans MA, Walter JE, Vliegenthart R, et al. . Disagreement of diameter and volume measurements for pulmonary nodule size estimation in CT lung cancer screening. Thorax 2018;73:779–81. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walter JE, Heuvelmans MA, Ten Haaf K, et al. . Persisting new nodules in incidence rounds of the Nelson CT lung cancer screening study. Thorax 2019;74:247–53. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yousaf-Khan U, van der Aalst C, de Jong PA, et al. . Final screening round of the Nelson lung cancer screening trial: the effect of a 2.5-year screening interval. Thorax 2017;72:48–56. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baldwin DR, Duffy SW, Devaraj A, et al. . Optimum low dose CT screening interval for lung cancer: the answer from Nelson? Thorax 2017;72:6–7. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heuvelmans MA, Oudkerk M. Appropriate screening intervals in low-dose CT lung cancer screening. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2018;7:281–7. 10.21037/tlcr.2018.05.08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horeweg N, van Rosmalen J, Heuvelmans MA, et al. . Lung cancer probability in patients with CT-detected pulmonary nodules: a prespecified analysis of data from the Nelson trial of low-dose CT screening. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:1332–41. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70389-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robbins HA, Berg CD, Cheung LC, et al. . Identification of candidates for longer lung cancer screening intervals following a negative low-dose computed tomography result. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019;111:996–9. 10.1093/jnci/djz041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pastorino U, Sverzellati N, Sestini S, et al. . Ten-Year results of the multicentric Italian lung detection trial demonstrate the safety and efficacy of biennial lung cancer screening. Eur J Cancer 2019;118:142–8. 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Field JK. Discussant : de Koning H, Presentation, effects of volume CT lung cancer screening — mortality results of the Nelson randomised-controlled population-based screening trial. IASLC 19th world conference on lung cancer. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: IASLC, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pastorino U, Silva M, Sestini S, et al. . Prolonged lung cancer screening reduced 10-year mortality in the mild trial: new confirmation of lung cancer screening efficacy. Ann Oncol 2019;30:1162–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdz117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callister MEJ, Baldwin DR, Akram AR, et al. . British thoracic Society guidelines for the investigation and management of pulmonary nodules. Thorax 2015;70 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):ii1–54. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pyenson B, Dieguez G. 2016 reflections on the favorable cost-benefit of lung cancer screening. Ann Transl Med 2016;4 10.21037/atm.2016.04.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pyenson BS, Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, et al. . Offering lung cancer screening to high-risk Medicare beneficiaries saves lives and is cost-effective: an actuarial analysis. Am Health Drug Benefits 2014;7:272–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villanti AC, Jiang Y, Abrams DB, et al. . A cost-utility analysis of lung cancer screening and the additional benefits of incorporating smoking cessation interventions. PLoS One 2013;8:e71379 10.1371/journal.pone.0071379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu GCW, Lazare K, Sullivan F. Serum and blood based biomarkers for lung cancer screening: a systematic review. BMC Cancer 2018;18:181 10.1186/s12885-018-4024-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seijo LM, Peled N, Ajona D, et al. . Biomarkers in lung cancer screening: achievements, promises, and challenges. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:343–57. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.11.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amos CI, Brennan PJ, Hung RJ, et al. . Integrative analysis of lung cancer etiology and risk, 2018. Available: http://grantome.com/grant/NIH/U19-CA203654-01A1 [Accessed 12 Mar 2019].

- 30.Rydzak CE, Armato SG, Avila RS, et al. . Quality assurance and quantitative imaging biomarkers in low-dose CT lung cancer screening. Br J Radiol 2018;91:20170401 10.1259/bjr.20170401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sevick-Muraca EM, Frank RA, Giger ML, et al. . Moonshot acceleration factor: medical imaging. Cancer Res 2017;77:5717–20. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Field JK, Mulshine JL. IASLC leads the International collaboration on data sharing (IASLC- ELIC-CCTRR) world conference lung cancer 2018.

- 33.Xia C, Rook M, Pelgrim GJ, et al. . Early imaging biomarkers of lung cancer, COPD and coronary artery disease in the general population: rationale and design of the ImaLife (imaging in lifelines) study. Eur J Epidemiol 2019;18 10.1007/s10654-019-00519-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Assen M, van Dijk R, Kuijpers D, et al. . T1 reactivity as an imaging biomarker in myocardial tissue characterization discriminating normal, ischemic and infarcted myocardium. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;35:1319–25. 10.1007/s10554-019-01554-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]