Abstract

The 3-(3-hydroxyalkanoyloxy)alkanoate (HAA) synthase RhlA is an essential enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of HAAs in Pseudomonas and Burkholderia species. RhlA modulates the aliphatic chain length in rhamnolipids, conferring distinct physicochemical properties to these biosurfactants exhibiting promising industrial and pharmaceutical value. A detailed molecular understanding of substrate specificity and catalytic performance in RhlA could offer protein engineering tools to develop designer variants involved in the synthesis of novel rhamnolipid mixtures for tailored eco-friendly products. However, current directed evolution progress remains limited due to the absence of high-throughput screening methodologies and lack of an experimentally resolved RhlA structure. In the present work, we used comparative modeling and chimeric-based approaches to perform a comprehensive semi-rational mutagenesis of RhlA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Our extensive RhlA mutational variants and chimeric hybrids between the Pseudomonas and Burkholderia homologs illustrate selective modulation of rhamnolipid alkyl chain length in both Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia glumae. Our results also demonstrate the implication of a putative cap-domain motif that covers the catalytic site of the enzyme and provides substrate specificity to RhlA. This semi-rational mutant-based survey reveals promising ‘hot-spots’ for the modulation of RL congener patterns and potential control of enzyme activity, in addition to uncovering residue positions that modulate substrate selectivity between the Pseudomonas and Burkholderia functional homologs.

Keywords: lipids, biosurfactants, enzymes, substrate specificity, microbiology

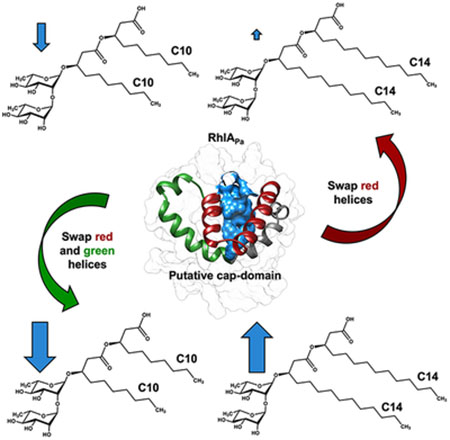

Graphical Abstract

Chimeric hybrids between the Pseudomonas and Burkholderia homologs of RhlA illustrate selective modulation of rhamnolipid alkyl chain length production (blue arrows), implicating a putative cap-domain motif that covers the catalytic site and provides substrate specificity to the enzyme. This semi-rational mutant-based survey reveals promising ‘hot-spots’ for the modulation of rhamnolipid congener patterns and potential control of enzyme activity, in addition to uncovering residue positions that modulate substrate selectivity between these functional homologs.

INTRODUCTION

Rhamnolipids (RLs) are glycolipid compounds produced by a limited number of bacterial species, including Pseudomonas and Burkholderia spp. [1]. RLs are attractive biosurfactants exhibiting good biodegradability, broad structural diversity and low toxicity [1, 2]. These features make them promising biotechnological metabolites in a wide variety of applications [3], including the cosmetic [4], detergent [5], agricultural [6], pharmaceutical [7], oil recovery [8], and bioremediation fields [9, 10]. RLs belong to a family of amphiphilic compounds that share a hydroxylated lipidic moiety (3-(3-hydroxyalkanoyloxy)alkanoate (HAA) coupled with a sugar moiety corresponding to one or two rhamnose units [11, 12]. RLs are produced through a multi enzymatic process involving enzymes RhlA, RhlB, RhlC, and RmlBDAC. The lipidic precursor of RLs (HAA) is synthesized by RhlA, which catalyzes the esterification between two units of hydroxylated fatty acids to form a di-lipid [13–16] (Figure 1). RhlB further catalyzes the condensation of one unit of dTDP-L-rhamnose through an O-glycosidic bond with the HAA moiety [12, 13, 16]. A second unit of dTDP-L-rhamnose can be condensed with the mono-rhamnolipid formed through an α-1,2-glycosidic bond catalyzed by RhlC [17, 18]. Enzymes encoded by the rmlBDAC operon provide the TDP-L-rhamnose [19]. Two metabolic pathways have been proposed to provide hydroxylated fatty acids for HAA synthesis. While Zhu and Rock showed that fatty acids are linked to an acyl carrier protein (ACP) to be used by RhlA in vitro – thus suggesting that FAS II is the default metabolic pathway [15] – recent isotopic tracing investigation performed in vivo suggested that β-oxidation is the main supplier of lipid precursors to RLs [20, 21].

Figure 1.

Proposed hydroxyacyl esterification mechanism catalyzed by RhlA. The top left panel shows the free enzyme with the putative catalytic triad (Ser102, Asp223 and His251) and two main chain amide groups (NH) acting as the oxyanion hole. The first step of the reaction involves binding of the first substrate to the active site, i.e. hydroxyacyl-ACP (in blue). His251 acts as a catalytic base to deprotonate Ser102, which becomes reactive and performs nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of the substrate, yielding an enzyme-substrate complex with respective tetrahedral intermediate stabilization (top and middle right panels). Breakdown of the tetrahedral intermediate leads to the release of ACP and formation of a hydroxyacyl enzyme intermediate (middle and bottom right panels). A second hydroxyacyl-ACP substrate binds to the acyl-enzyme intermediate (bottom right panel). His251 deprotonates the hydroxyl group of the β-fatty acid carbon on the second substrate molecule to activate it, catalyzing the nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of the hydroxyacyl enzyme complex to form a second tetrahedral intermediate (bottom right and left panels). Lastly, breakdown of this tetrahedral intermediate releases a dilipid and restores the free enzyme state (middle and top left panels). This proposed catalytic mechanism is based upon classical enzyme-catalyzed esterification reactions and ester hydrolysis mechanisms catalyzed by proteases [93, 94].

The industrial use of RLs currently poses two major challenges, i.e. they are produced as a complex mixture of congeners with significantly distinct structural and molecular properties [2, 22, 23], in addition to being produced at much higher costs relative to synthetic surfactants [24]. As a result, improving production yields and achieving competitive advantage in the biosurfactant market requires combining approaches that lower production costs with strategies that target high-performance RL cell synthesis [25]. Furthermore, the ability to manipulate RL congener mixture composition would offer significant advantage to better exploit RL properties in selected applications [23, 26, 27]. To this day, many studies have addressed these challenges by using genetically engineered, non-pathogenic microbial hosts to synthesize RLs [23, 28–31]. However, engineered strains are often incapable of achieving high production yields relative to the well-characterized high RL producer Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This is attributed to the complexity of the genetically regulated pathways controlling in vivo RL production and/or the inability of efficiently controlling heterologous gene expression leading to metabolic perturbations. In fact, expression of rmlBDAC, rhlAB and rhlC in P. aeruginosa is mainly regulated by the rhl quorum sensing system [18, 32, 33], which in turn is part of a complex genetic regulation cascade [34]. According to a previous report [35], RhlA is overexpressed in cultures optimized for the overproduction of RLs, suggesting that RhlA acts as a key enzyme providing the lipidic flux toward the RL biosynthesis pathway. Thus, HAA biosynthesis could act as the rate-limiting step of RL production.

To the best of our knowledge, only one study previously reported the molecular evolution of RhlB to improve RL production from the RL biosynthesis pathway [27]. The lack of a reliable high-throughput screening methodology for RL production and the absence of a crystallographically-resolved protein structure for RhlA, RhlB, or RlhC severely restrict the possibility of using directed evolution approaches to improve RL biosynthesis. To partly overcome such limitations, we combined homology modeling and targeted structural mutagenesis of RhlA from P. aeruginosa (RhlAPa) to investigate its potential to increase RL production and to modulate RL congener mixtures in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia glumae. We performed homology modeling of the RhlAPa enzyme using structural homologs of the α/β hydrolase superfamily to perform structure-guided rational mutagenesis at targeted positions. Experimental validation of selected positions by alanine scanning allowed us to identify the catalytic site of RhlAPa, which was found to be covered by a putative cap-domain motif. Since cap-type domains play a crucial role in α/β hydrolase ligand selectivity [36–41], we also performed the mutational exploration of this potentially important RhlA motif. Since various Burkholderia species have the ability to produce RLs that differ in RL alkyl chain length relative to P. aeruginosa [42–45], we also used RhlA from Burkholderia glumae (RhlABg) as a comparative partner to develop chimeric RhlABg-RhlAPa hybrid biocatalysts. Our aim was to characterize the structure-function relationship between the putative cap-domain and substrate binding/selectivity in these structural and functional homologs. Results from chimeric RhlA enzymes from Pseudomonas and Burkholderia species illustrate that substrate selectivity of RhlAPa is partly located in the putative cap-domain motif. Finally, we found that selected point mutants are sufficient to increase the catalytic efficiency of RhlAPa expressed in P. aeruginosa and B. glumae. We identified nine mutations with increased in vivo RL biosynthesis, resulting in doubling of RL production relative to WT RhlAPa. Our results suggest that these replacements could be involved in stabilization of RhlA substrates during HAA synthesis.

RESULTS

Substrate selectivity of RhlA from P. aeruginosa and B. glumae.

P. aeruginosa produces RLs with fatty acid chain lengths varying from 8 to 12 carbons (C8-C12), favoring the predominant C10-C10 dilipid [46]. RhlAPa also shows remarkably high in vitro preference for C10 (87.3 %) alkyl chain length over C8 (8.5 %) and C12 (4.1 %) substrates [15]. Nevertheless, enzyme selectivity for longer 3-hydroxyalkyl chain lengths (C14 and C16) remains uncharacterized. To verify whether P. aeruginosa produces C14 and C16 fatty acid precursors that could be used in RL biosynthesis, we cultured a PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7 strain in minimal medium supplemented with glycerol as the sole carbon source and analyzed the pattern of free 3-hydroxyfatty acids in early stationary growth phase by GC/MS. We observed that the rhlA-depleted PA14 strain supplies 3-hydroxyfatty acids with chain lengths varying from C8 to C14, with C8 and C10 being the most abundant (Table 1). The relative abundance of C14 was only ~2 % and C16 hydroxylated fatty acid was not detected. Since P. aeruginosa primarily synthesizes medium-sized chain hydroxyfatty acids (C8-C12) in early stationary phase, the production of larger alkyl chain HAA congeners is unlikely to be achieved with glycerol as the sole carbon source.

Table 1.

GC/MS analysis of free 3-hydroxy fatty acids from a PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7 strain in early stationary growth phase.

| Species | MW1 | MW2 of trimethylsilyl derivatives2 | Retention time (min) | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-OH-C8 | 160.1 | 304.2 | 10.54 | 33.9 |

| 3-OH-C10 | 188.1 | 332.2 | 11.23 | 50.5 |

| 3-OH-C12 | 216.1 | 360.3 | 11.80 | 13.7 |

| 3-OH-C14 | 244.1 | 388.2 | 12.31 | 1.9 |

Molecular weight calculations are based on the exact mass.

Trimethylsilyl derivative is of both the carboxylic group and the 3-hydroxyl group.

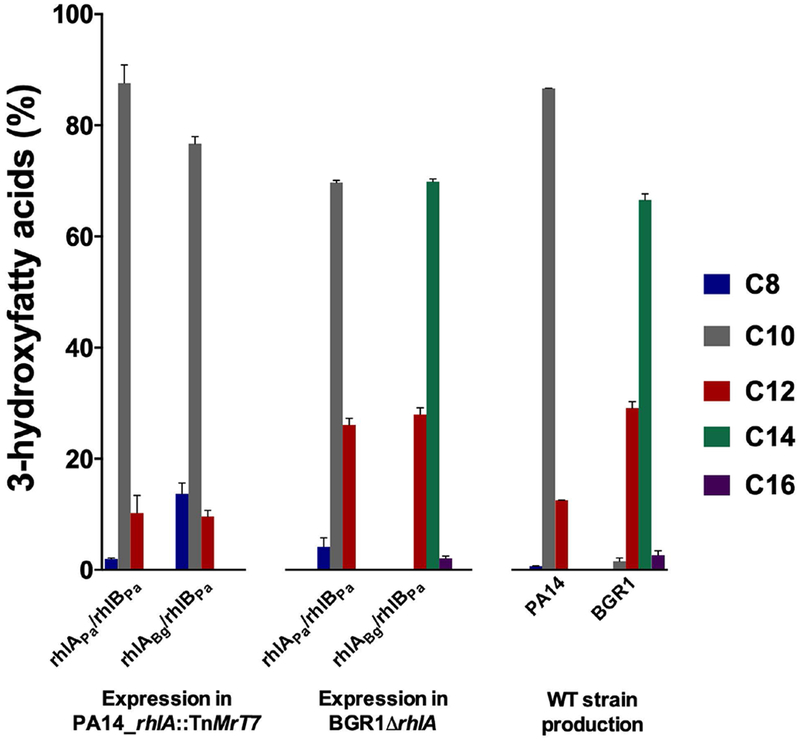

To circumvent the lack of longer C14 and C16 hydroxyfatty acids produced in P. aeruginosa, we considered the fact that B. glumae produces RLs with fatty acid chain lengths varying from C12 to C16, favoring the most abundant dilipid congener C14-C14 [45]. Thus, we complemented a B. glumae BGR1ΔrhlA mutant with native operon rhlAPa/rhlBPa. Again, we observed that the RL pattern exhibits 3-hydroxyfatty acid chain lengths ranging from C8 to C12, without production of C14 or C16 alkyl chains, similar to the wild-type RL pattern observed in P. aeruginosa (Figure 2). This result confirms that the fatty acid composition of the RL mixture observed in P. aeruginosa is due to the preference of RhlAPa for medium-sized substrates (C8 - C12) instead of the predominant length of the 3-hydroxyalkyl chain species provided by the bacterial host. Furthermore, we observed that B. glumae supplies a wider range of hydroxyfatty acid species than P. aeruginosa, including alkyl chain lengths ranging from C8 to C16. Nevertheless, upon expression of the hybrid operon rhlABg/rhlBPa in a BGR1ΔrhlA mutant, RLs carrying C12-C16 alkyl chains were detected, similar to the RL congener mixture observed in WT B. glumae (Figure 2). In contrast, expression of the hybrid operon rhlABg/rhlBPa in a PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7 mutant produces only RLs with alkyl chain lengths ranging from C8 to C12. Although RhlABg is a more permissive enzyme that produces both medium-sized and long-sized chain HAAs, this result suggests that the significant production yields of C14-HAAs in B. glumae is not exclusively dependent on the available 3-hydroxyfatty acids in this host, but also due to the intrinsic lower selectivity of RhlABg.

Figure 2.

3-hydroxyfatty acids produced by RhlAPa and RhlABg upon cross complementation assays with strains PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7 and BGR1ΔrhlA (WT operon rhlAPa/rhlBPa and hybrid operon rhlABg/rhlBPa). 3-hydroxyfatty acid production was calculated based on total HAAs, with mono- and di-RLs detected by LC/MS. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Error bars were calculated from standard deviation of three independent measurements (n = 3).

Substrate selectivity in RhlA.

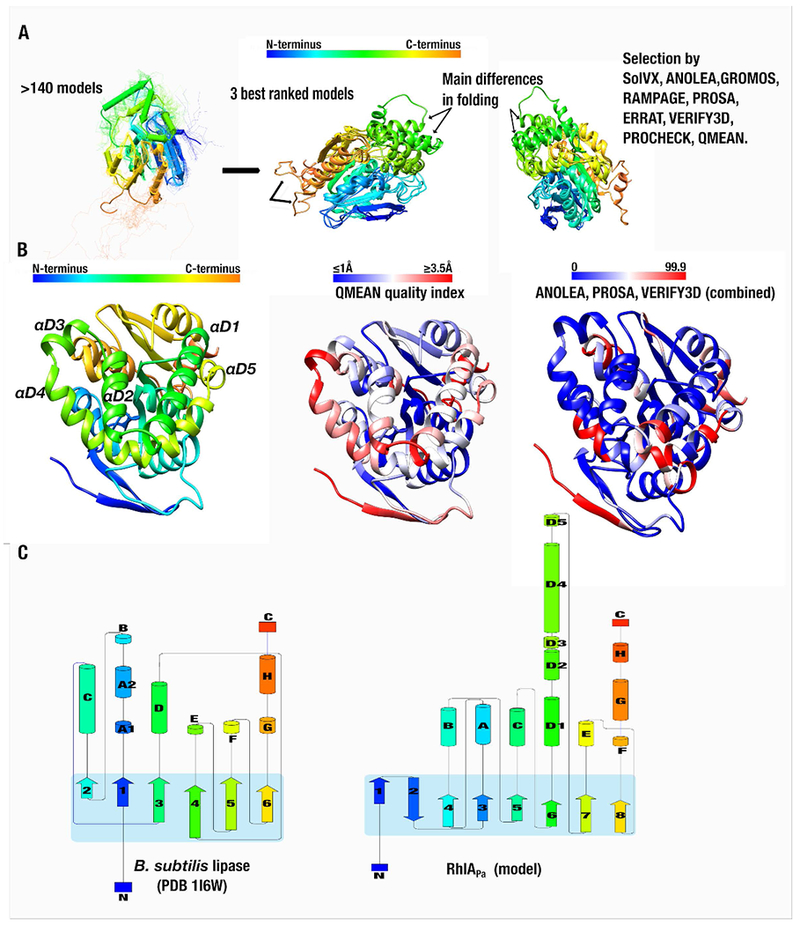

The three-dimensional structure of the RhlA enzyme has not been resolved. Consequently, to rationalize RL production yields and to understand RL congener selectivity at the molecular level, we used PSI-Blast and HHblits algorithms to identify the best structural template candidates to perform homology modeling on the RhlAPa target sequence [47, 48]. Both algorithms were intended to cover close and remote homolog detection. Template structures of proline iminopeptidase-related protein TTHA1809 (PDB entry 2YYS), amidohydrolase VinJ (PDB entry 3WMR), and α/β hydrolase from P. aeruginosa PAO1 (PDB entry 3OM8) were selected as the most promising template candidates. Although these all preserve the canonical α/β hydrolase fold, they nevertheless exhibit low sequence identity with RhlAPa (22%, 28.4%, and 21%, respectively). Because inaccuracies in homology modeling typically arise from errors in initial sequence alignments — and therefore inadequate template selection [49] — we used T-Coffee Expresso to evaluate local sequence alignment reliability between RhlAPa and the three template candidates. We also opted to build and challenge the validity of distinct homology model predictions for all three templates. This was warranted on the basis that templates exhibiting sequence identities below 30% tend to display broadly similar folds with different side chain packing and orientation, potentially leading to serious mispredictions [50]. As a result, we selected the prediction convergence of all template models to increase the reliability of our RhlA model (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

RhlAPa homology modeling procedure and validation. A) Based on template structures of proline iminopeptidase-related protein TTHA1809 (PDB entry 2YYS), amidohydrolase VinJ (PDB entry 3WMR), and α/β hydrolase from P. aeruginosa PAO1 (PDB entry 3OM8), 140 models were computed by independent homology modeling protocols. The most structurally and energetically favorable models were evaluated for a second round of validation (see Materials & Methods, Table 2, and Figure S1 for details). All models exhibited similar protein backbone architecture (left section of panel A). B) Comparison between the QMEAN quality index (middle section) and the combined tools of ANOLEA, PROSA, and VERIFY3D. The QMEAN index provides a scoring function for the quality estimation of protein structure models, highlighting the degree of confidence for every residue within the model structure (in Å). Similarly, the combined tools (right section of panel B) illustrate structure prediction certainty, represented by a scoring range value between 0 and 99.9 (high and low certainty, respectively). C) Comparative schematic topology between the best ranked RhlAPa model and the minimal α/β hydrolase fold of the Bacillus subtilis lipase (PDB entry 1I6W). The RhlAPa topology illustrates a central subdomain of 8 β-sheets (blue square), which is highly conserved in the α/β hydrolase superfamily (SCOP annotation [52]). N- to C-terminus color palettes are shared in all sections of the figure, except for the right sections of panel B.

Three independent homology modeling procedures (SWISS-MODEL, I-TASSER, and Robetta) were used, yielding a pool of 140 predicted RhlAPa structures with nearly identical fold and main structural differences located in the loop environments (Figure 3A). The best ranked models were subjected to a second round of robust structural and energetic validation, including atomic solvation to qualify side chain packing, Cα geometry structural evaluation, stereochemical quality, packing quality, and composite scoring function for quality estimation of homology models [51] (see Materials & Methods, Figure 3, and Table 2 for details). The best ranked structure supports the methodology and confirms that the topology of RhlAPa resembles that of the conserved α/β hydrolase superfamily (SCOP annotation [52]), preserving 8 β-strands at the core of the enzyme fold (Figure 3B–C). The main difference between the RhlAPa model and the canonical α/β hydrolase fold is the addition of a set of 5 α-helices in structural motif D (αD1-αD5, Figure 3C). As expected, the overall quality estimation index (QMEAN) and the combined tools of ANOLEA and VERIFY-3D confirmed that the N-terminal portion and the αD4 motif exhibit the lowest structural accuracy. Nevertheless, the predicted protein structure exhibits a global quality value comparable to similarly sized and folded experimental structures reported in the Protein Data Bank (Figures S1C).

Table 2.

Scoring functions obtained for the best ranking RhlAPa models calculated by homology modeling.

| Tool/Model | I-Tasser | Robetta | SWISS-MODEL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rampagea | |||

| AA in favored regions (%) | 79.5 | 94.9 | 89.3 |

| AA in allowed regions (%) | 14.7 | 4.1 | 8.9 |

| AA in outlier regions (%) | 5.8 | 1 | 1.9 |

| SolVXb | −31.2 | −129 | −68.3 |

| Verify3Dc (%) | 77.97 Warning |

90.85 Pass |

83.46 Pass |

| ERRATd (%) | 93.031 | 94.386 | 85.714 |

| PROCHECK (errors) | 23 | 18 | 27 |

| ANOLEA,GROMOSe (%) | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| QMEAN6 scoref | 0.62 | 0.742 | 0.627 |

Percentage of amino acid residues (AA) in favored, allowed, or outlier regions.

Solvation index: more negative values illustrate better structural packing, typically correlating with better model validation.

Percentage of amino acid residues in favored conformations, according to their local environment.

Percentage of residues with <95% confidence of statistical rejection compared to highly refined experimental structures.

Relative ranking of the best three models considering combined simulation outcomes performed using ANOLEA and GROMOS.

Absolute QMEAN6 quality score, ranging from 0 to 1 (higher value = higher model reliability).

We used the TM-align and COACH tools on the best ranked structure to identify residues potentially involved in the catalytic function of RhlAPa [53, 54]. A set of 8 residues were identified as catalytically relevant positions (A36, M37, W103, A128, L131, L199, E224 and Y225), with S102, D223, and H251 acting as a potential catalytic triad (Figure 4A). An alanine scanning exploration of this putative catalytic triad showed that substitution of any of the residues at positions 102, 223, and 251 generated a catalytically inactive RhlA enzyme. This was confirmed by the lack of HAA or RL production in a PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7 strain expressing these single-site mutational variants (Figure 4B). The potential role of the proximal E224 residue as the acid component of the catalytic triad was discarded due to the fact that the loss-of-function E224A variant did not affect RL production in P. aeruginosa (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Single-site mutagenesis of putative active-site residues in RhlAPa. A) Structural location of targeted residues for mutagenesis, based on TM-align and COACH predictions. The putative catalytic triad is depicted in blue and side-chains of other targeted residues are color-coded. Amino acid substitutions that reduced enzyme activity ≥ 50% are shown in red, residue positions where at least one amino acid substitution decreased RL synthesis ≤ 50% are shown in yellow, and residue positions where at least one amino acid substitution increased enzyme activity relative to WT are shown in green. Secondary structure labels are identical as in Figure 3B. B) Total rhamnolipid production of a P. aeruginosa (PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7) strain expressing single-site mutational variants of RhlAPa. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Error bars were calculated from standard deviation of three independent measurements (n = 3). C) Geometry and orientation of the predicted RhlA catalytic triad is compared to experimental α/β hydrolase structures, i.e. lipase B from Pseudozyma antarctica (PDB entry 1TCA) and triacylglyceride lipase from Rhizomucor miehei (PDB entry 3TGL).

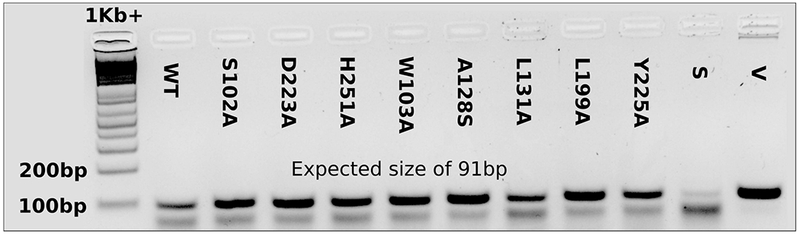

Since the P. aeruginosa and B. glumae bacterial systems used to test rhamnolipid production express RhlA at constitutive levels and therefore yield low cellular enzyme concentrations, it was impossible for us to confirm WT or mutant RhlA expression on SDS-PAGE over empty strain controls. The lack of either a proper expression tag and/or lack of commercially available anti-RhlA antibody also precluded us from performing Western Blot analyses to confirm protein expression of all RhlA variants. Consequently, we used a reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to confirm that the mutated genes of inactive variants are well transcribed in the PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7 system (Figure 5). These results suggest that loss of rhamnolipid synthesis by RhlA is caused by loss-of-function mutations rather than lack of proper enzyme expression or misfolding. This observation is further supported by the fact that no RhlA protein band was ever observed on SDS-PAGE, including for the highly active WT RhlA enzyme and for all rhamnolipid producing mutational variants. Overall, these results support the hypothesis that S102, D223, and H251 act as the catalytic triad of RhlAPa, which is further supported by strict evolutionary sequence conservation and highly similar structural organization of the putative catalytic triad residues between RhlA and homologous α/β hydrolase superfamily members (Figure 4C).

Figure 5.

Gene expression evaluation of RhlA variants in P. aeruginosa PA14_ rhlA::MrT7-. RNA was extracted from fresh cultures, treated with Turbo™ DNase and submitted to reverse transcription using oligo(dT)20 as primers to generate cDNA. PCR was performed on cDNA obtained from strains transformed with wild type (WT) or RhlA mutant expression vectors, using primers RT-RhlA-F: 5’-TTTCACATCGACCAGGTGCT-3’, and RT-RhlA-R: 5’-TGCCGTTGATGAAATGCACG-3’. The untransformed strain (S) as well as the pUCP26A expression vector containing the wild type protein sequence (V) are shown as controls. PCR products were separated on a 3% agarose gel and visualized using GelRed™.

Our homology model suggests that catalytic residues S102, D223, and H251 are not surface-exposed but rather located in the core of the enzyme and covered by the abovementioned structural α-helix motif (αD1– αD5), spanning residues 132-190 between strands β6 and β7 (Figure 4A). Homologous α/β hydrolases, such as lipases, also exhibit buried active sites under similarly shaped secondary structure elements, forming a flap (or a cap-domain) that can experience a conformational change to allow substrate access [55]. These extra helices in RhlAPa could therefore act as a similarly shaped cap-domain previously reported in other α/β hydrolases (Figure 6A) [56]. Therefore, we hypothesized that residues 132-190 in RhlAPa could act as a key domain allowing substrate recognition and discrimination, whereby this α-helix motif would be critical to substrate selectivity in RhlAPa.

Figure 6.

Selectivity performance of the RhlA chimeric proteins. A) Chimeric α-helix motif swapping from RhlABg to RhlAPa. RhlAH-1 corresponds to RhlAPa with swapping of helices αD1 and αD2 from RhlABg (dark red); RhlAH-2 corresponds to RhlAH-1 with swapping of αD3 and a section of αD4 from RhlABg (green); and RhlAH-3 corresponds to RhlAH-2 with additional swapping of the terminal αD4 motif (gray). The surface of the putative active-site channel is depicted in blue. B) Synthetic profiles of RhlAH-1, RhlAH-2, and RhlAH-3 relative to wild-type RhlA from P. aeruginosa and B. glumae (RhlAPa and RhlABg, respectively) under the metabolic environments of PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7 (left) and BGR1ΔrhlA (right). 3-hydroxyfatty acid yields were calculated from total HAAs, including mono- and di-RLs detected by LC/MS. Error bars were calculated from standard deviation of three independent measurements (n = 3).

To experimentally challenge this hypothesis, we considered the fact that RhlAPa and RhlABg display distinct substrate selectivity. Both RhlAPa and RhlABg share the α/β hydrolase fold with conserved catalytic residues, exhibiting 62% (45%) sequence similarity (identity) and preserving the abovementioned putative cap-domain motif. To explore the role of specific residues in substrate recognition and discrimination within the putative cap-domain, we performed single-site amino acid substitutions at non-conserved residue positions between RhlAPa and RhlABg (Figure 7). Based on total production yields of HAA and RL congeners detected by LC/MS, we compared changes in chain length incorporation for each RhlAPa variants. Seven amino acid substitutions in the putative cap-domain of RhlAPa completely obliterated the production of RLs, while some point mutations induced the production of RLs at low levels, thus preventing the analysis of specific congeners and further confirming the catalytic importance of this motif in RhlA (Table 3). Among active RhlAPa variants, amino acid substitutions did not exhibit changes in congener chain length ratios. However, the A182P substitution (predicted on αD4) exhibited a ≈7% increase (20% to 27%) in C12 chain length production when expressed in strain BGR1ΔrhlA (Table 4).

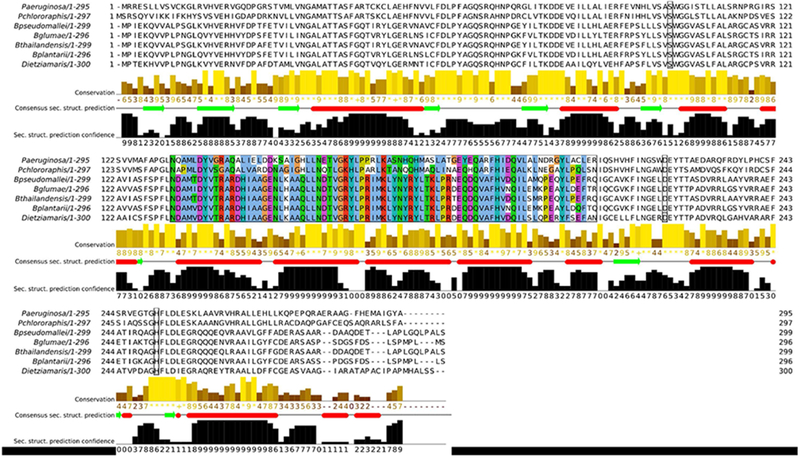

Figure 7.

Multiple sequence alignment of RhlA homologs. Sequence alignment shows conserved catalytic residues 102, 223 and 251 (black border), and conserved positions within the putative cap-domain (Clustal default coloring code). RhlA sequences were selected from RL producer strains expressing genes involved in RL biosynthesis. Clustal default coloring code corresponds to: blue, hydrophobic residues (A, I, L, M, F, W and V); red, positively charged residues (K and R); magenta, negatively charged residues (E and D); green, polar residues (N, Q, S and T); pink, cysteine residues; orange, glycine residues; yellow, proline residues; cyan, aromatic residues (H and Y); and white, non-conserved residues and gaps. Alignment was generated with Clustal Omega [95–97]. Consensus secondary structure prediction was performed with JPred4 [98].

Table 3.

Catalytic performance of RhlA from P. aeruginosa upon substitution of non-conserved residues on the cap-domain (relative to RhlA from B. glumae).

| Mutation | Relative activity (%)ab | Mutation | Relative activity (%)ab |

|---|---|---|---|

| A144D | 78 (± 2)d | S173Y | 10 (± 1)c |

| L145H | 60 (± 4)d | H177Y | 0 |

| E147A | 85 (± 5)d | A179T | 73 (± 4)d |

| L148A | 106 (± 1)d | A182P | 39 (± 2) |

| D149G | 86 (± 11)d | T183R | 0 |

| K151N | 8 (± 2)c | G184D | 84 (± 3)d |

| S152L | 29 (± 2)c | Y186Q | 0 |

| A153H | 24 (± 7)c | E187D | 0 |

| H156Q | 66 (± 9)d | R190A | 0 |

| E160D | 80 (± 6)d | D194N | 63 (± 3)d |

| K164R | 156 (± 13)d | A198E | 105 (± 3)d |

| P168R | 0 | L199M | 4 (± 2)c |

| R169I | 16 (± 2)c | R202E | 0 |

Catalytic activity is relative to the WT RhlAPa performance with standard deviation (SD) obtained from triplicate experiments.

Rhamnolipid congeners detected by LC/MS.

Low production yields of this mutant hampered proper identification and quantification of congeners.

No differences were observed in the RL congener pattern with respect to WT.

Table 4.

Rhamnolipid congener pattern observed upon expression of the RhlAPa-A182P/RhlBPa variant with respect to RhlAPa-WT/RhlBPa in a BGR1ΔrhlA background.

| Variant | C8 (%)* | C10 (%)* | C12 (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| RhlAPa-WT | 5.4 (± 0.6) | 74.3 (± 0.6) | 20.3 (± 0.6) |

| RhlAPa-A182P | 7.9 (± 0.6) | 65.1 (± 1.1) | 27.0 (± 1.3) |

Fatty acid contribution were calculated from LC/MS negative mode analysis of congeners C8-C8 (m/z 301.3), Rha-C8-C8 (m/z 447.3), Rha-Rha-C8-C8 (m/z 593.5), C8-C10/C10-C8 (m/z 329.3), Rha-C8-C10/Rha-C10-C8 (m/z 475.4), Rha-Rha-C8-C10/Rha-Rha-C10-C8 (m/z 621.6), C10-C10 (m/z 357.3), Rha-C10-C10 (m/z 503.4), Rha-Rha-C10-C10 (m/z 649.5), C10-C12/C12-C10 (m/z 385.3), Rha-C10-C12/Rha-C12-C10 (m/z 531.4), Rha-Rha-C10-C12/Rha-Rha-C12-C10 (m/z 677.5), C12-C12 (m/z 413.6), Rha-C12-C12 (m/z 559.7), and Rha-Rha-C12-C12 (m/z 705.5). No others congeners longer than C12 were detected.

Since point mutations were insufficient to fully explain the involvement of the putative cap-domain in substrate recognition, we further opted to sequentially swap residues 132-165, 132-190, and 132-210 of RhlABg with the corresponding positions in RhlAPa, generating chimeric enzymes RhlAH-1, RhlAH-2, and RhlAH-3, respectively. Chimeric enzymes were built and expressed using the constitutive expression vector pUCP26, yielding plasmids pCD6 (rhlAH-1/rhlBPa), pCD7 (rhlAH-2/rhlBPa), and pCD8 (rhlAH-3/rhlBPa) (Figures 6, S2, and S3). This effectively encoded full length RhlAPa with αD1-αD2 from RhlABg (RhlAH-1), full length RhlAH-1 with swapping of αD3 and a section of αD4 from RhlABg (RhlAH-2), and RhlAH-2 with additional swapping of the terminal αD4 motif (RhlAH-3) (Figure 6A). Upon expression of these chimeric enzymes in strain PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7, HAA and RL analyses showed a downward trend in C10 substrate synthesis (≈30% lower production for RhlAH-2 and RhlAH-3) and an increase in incorporation of C12 (≈20%) relative to ratios observed with WT RhlAPa (Figure 6B). Nevertheless, the resulting 3-hydroxyfatty acids consumed by these chimeric enzymes retained C8 to C12 chain lengths, consistent with prior identification of the 3-hydroxyfatty acid pool available in this bacterium (Table 1).

To evaluate the relative contribution of αD1-αD5 in the modulation of RhlA selectivity, the chimeric enzymes (RhlAH-1, RhlAH-2 and RhlAH-3) were also expressed in the BGR1ΔrhlA strain. This provided a broader range of 3-hydroxyfatty acid synthesis profiles, including chain lengths ranging from C8 to C16. Interestingly, RhlAH-1 expression exhibited ≈50% decrease in C10 and ≈100% increase in C12 congener synthesis relative to WT RhlAPa (Figure 6B). Unlike WT RhlAPa, this chimera can synthesize C14-HAA and RL congeners. Also, RhlAH-2 and RhlAH-3 synthesize a higher ratio of longer alkyl chain HAAs, mainly the C12 and C14 congeners (with only minor differences). These results confirm the involvement of residues within αD1-αD3 and the first half of αD4 (132-190) in the selectivity of R-3-hydroxyfatty acids exhibiting C12 to C14 chain lengths in RhlABg (Figure 6B). Furthermore, the fact that C12 production was doubled after αD1 and αD2 substitution (residues 132-165) strongly suggests that C12 chain length selectivity partly resides within these α-helices of the putative RhlA cap-domain. In contrast, C14 hydroxy fatty acid selectivity appears to lie within the αD3 and αD4 helices, as illustrated by the significantly increased C14 profiles of RhlAH-2 and RhlAH-3 chimeras (Figure 6B).

Exploring potential active-site residues that increase the catalytic efficiency of RhlAPa.

To increase the catalytic activity of RhlAPa, we first explored residues in the vicinity of the modeled catalytic triad of RhlAPa (Figure 4A). Based on our TM-align and COACH analyses (see Materials & Methods for details), we explored eight residue positions that could be involved in stabilization of the substrate-enzyme complex, i.e. A36, M37, W103, A128, L131, L199, E224, and Y225 [54, 57]. Through alanine scanning, we showed that M37, W103, L199, and Y225 were critical to RhlAPa activity, as their alanine substitutions led to the complete abrogation of enzyme activity (Figure 4B). To identify whether mutations at these positions could potentially increase RhlAPa activity, substitutions with similar physicochemical properties were also performed. M37L was the only beneficial replacement, exhibiting increased RL production (≈25% improvement). From the eight positions explored, all were shown to be important for RhlAPa activity and/or stability since all substitutions (except for M37L) decreased RhlAPa activity at least 50%.

Targeting residues 132-210 as a promising strategy to increase or modulate the catalytic activity of RhlA.

Considering that the putative cap-domain (residues 132-210) participates in substrate recognition, this region represents a promising mutagenesis target for modulating or controlling RhlA activity and/or specificity. Since protein hinges are often involved in controlling conformational exchange linked with enzyme activity [58], we explored putative cap-domain hinge regions for mutagenesis, selecting positions located in close proximity to the N-terminal of the αD1 helix (132, 227, 230), between αD2-αD3 helices (169 and 256), between αD3-αD4 helices (66, 69, 167, 168, and 192), and in C-terminal of the αD4 helix (79, 202, and 204) (Figure 8 and Table 5). We were especially interested in polar and electrostatic residues, as time-resolved forming and breaking of electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding interactions were shown to affect local flexibility and/or stability, potentially promoting broader conformational changes of cap-domain helices involved in catalysis.

Figure 8.

Catalytic performance of RhlAPa mutants after extensive mutagenesis exploration of the putative cap-domain motif. A) Effect of point mutations in the putative cap-domain of RhlAPa (blue helices), color-coded by % rhamnolipid production levels relative to WT RhlAPa. B) Top panel: Predicted RhlAPa cap-domain access channels that connect the solvent environment with the active-site cavity of the enzyme (in yellow). Bottom panel: specific mutations that increase catalytic activity of RhlAPa, with channels numbered 1 through 4 according to their respective volume and surface entrance (biggest to smallest). All panels maintain the same color scheme and orientation as panel A. Only side chains of favorable substitutions are illustrated (in purple) and the catalytic triad is depicted in red. C) Increased rhamnolipid production of favorable mutations relative to WT RhlAPa. Error bars were calculated from standard deviation of three independent measurements (n = 3).

Table 5.

Catalytic performance of RhlAPa variants explored in this study.

| Mutation | Relative activity* | Mutation | Relative activity* | Mutation | Relative activity* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A36L | 6 | D137A | 32 (± 3) | R169K | 126 (± 10) |

| A36V | 13 (± 2) | D137E | 51 (± 8) | E185A | 12 (± 1) |

| A36M | 43 (± 7) | Y138A | 12 (± 1) | Q188N | 29 (± 3) |

| A36I | 7 | Y138F | 14 (± 1) | A189P | 1 |

| A36G | 2 | R141A | 63 (± 5) | H192R | 1 |

| M37A | 0 | R141A-K164R | 97 (± 5) | H192A | 9 (± 2) |

| M37V | 43 (± 4) | R141K | 121 (± 11) | H192K | 5 (± 1) |

| M37I | 9 (± 1) | R141A-T161A-K164R | 0 | A198P | 10 (± 1) |

| M37L | 123 (± 6) | A142P | 2 | L199A | 0 |

| M37F | 12 (± 1) | A142P-A144P | 2 | L199M | 4 (± 2) |

| Q66R | 68 (± 7) | L145H | 60 (± 4) | L199V | 29 (± 9) |

| Q69K | 8 (± 1) | L145A | 27 (± 4) | L199I | 54 (± 13) |

| Q69N | 138 (± 10) | L145I | 23 (± 2) | R202K | 201 (± 4) |

| Q69R | 0 | L146I | 56 (± 9) | R202E | 0 |

| K79Q | 6 | L148I | 86 (± 13) | R202D | 0 |

| K79R | 9 (± 1) | L157A | 5 | Y204E | 93 (± 7) |

| S102A | 0 | L157I | 18 (± 4) | Y204D | 88 (± 7) |

| W103A | 11 (± 1) | L157P | 2 | D223A | 0 |

| W103Y | 9 (± 1) | L158A | 3 | E224A | 99 (± 18) |

| A128G | 63 (± 14) | L158P | 2 | E224D | 134 (± 2) |

| A128V | 55 (± 8) | L158I | 101 (± 5) | Y225A | 0 |

| A128L | 7 (± 1) | E160A | 2 | Y225F | 14 (± 1) |

| A128I | 5 (± 2) | T161A | 57 (± 3) | Y225S | 6 |

| A128W | 0 | T161S | 23 (± 5) | T227E | 31 (± 2) |

| A128S | 57 (± 7) | K164R-T227S | 60 (± 8) | T227D | 38 (± 2) |

| L131A | 21 (± 2) | K164R-Y165F | 59 (± 6) | T227S | 145 (± 15) |

| L131V | 0 | K164A | 55 (± 10) | T227D | 38 (± 6) |

| L131I | 86 (± 24) | Y165A | 4 | D230E | 148 (± 24) |

| N132K | 3 | Y165F | 187 (± 16) | H251A | 0 |

| N132R | 15 (± 1) | Y165F-T227S | 13 | E256D | 0 |

| N132Q | 11 (± 1) |

Catalytic activity is relative to the WT RhlAPa performance with standard deviation (SD) obtained from triplicate experiments.

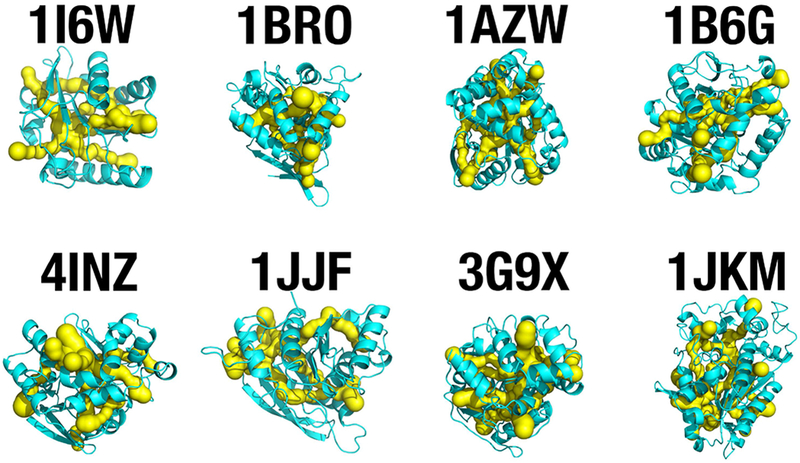

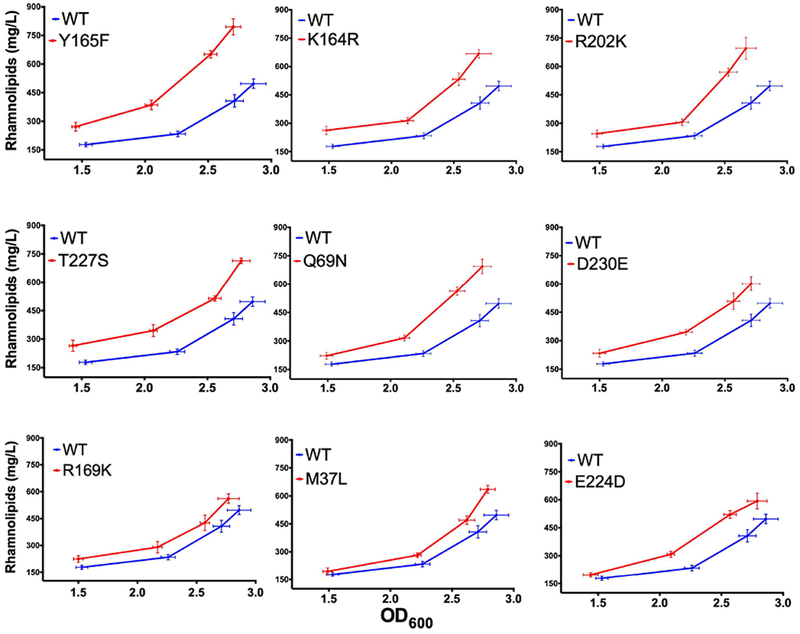

Based on the common occurrence of active-site access channels in the canonical α/β hydrolase fold (Figure 9), we also used our model to identify putative substrate access channels in RhlAPa (Figure 8B). Our observation provided justification for the mutational exploration of positions surrounding potential active-site channels (141, 161, 164, 165, and 224). Selected residues were replaced by amino acids with similar physicochemical properties and size (Table 5). Mutagenesis of potential hinges, access channels, and C-terminal helices resulted in 85 distinct point mutants at 39 positions, offering broad exploration of this particular RhlA motif (Figure 8A and Table 5). Most mutants exhibited similar substrate selectivity as WT RhlAPa, with an increase in synthetic activity for RhlAPa variants Q69N, K164R, Y165F, R169K, R202K, E224D, T227S, and D230E. The maximum increase in RL synthetic activity was observed for variants Y165F and R202K, both respectively showing ≈100% improvement relative to WT RhlAPa (Figure 8). Within these 8 activity-promoting variants, the only non-polar replacement was found to be the Tyr to Phe residue at position 165 (near the catalytic serine), with other substitutions preserving polar and electrostatic properties, and 6 out of 8 changes primarily reducing length or size of the residue side chain without affecting physicochemical properties. Surprisingly, with the exception of Q69N (which is located in a loop below αD4), these mutations delineate three potential access channels that could be involved in connecting the surface of RhlAPa to its active site (Figure 8B). Additionally, three mutations that promote catalytic activity in RhlAPa (K164R, Y165F, E224D) delineate the main active-site channel in our model (Figure 8B, channel 1).

Figure 9.

SCOP active-site access channel extraction from 8 distinct members of the canonical α/β hydrolase superfamily [52]. The CHEXVIS tool [81] was applied to analyze whether internal packing of these α/β hydrolase members allows for internal channel formation, as observed with the RhlAPa model (Figure 8B). Predicted access channels that connect the solvent environment with the active-site cavity of the enzyme are shown in yellow. The experimental structures used are: minimal lipase from Bacillus subtilis (PDB entry 1I6W), bromoperoxidase from Kitasatospora aureofaciens (1BRO), proline iminopeptidase from Xanthomonas citri (1AZW), haloalkane dehalogenase from Xanthobacter autotrophicus (1B6G), epoxide hydrolase from Bacillus megaterium (4INZ), carboxylesterase from Clostridium thermocellum (1JJF), haloalkane dehalogenase from Rhodococcus rhodochrous (3G9X), and carboxylesterase from Bacillus subtilis (1JKM).

Two factors affecting RhlAPa mutant efficiency were considered to further corroborate our experimental data: (1) the fact that our activity screen was performed using in vivo models, which are expected to exhibit cell growth differences, and (2) the fact that RL production is controlled by quorum sensing, imposing a delayed RL production to clones exhibiting slower growth, therefore lowering cell density. To eliminate cell growth effects on quantification, we experimentally validated whether the proposed substitutions would improve HAA and RL production during the entire fermentation period. Strains expressing engineered RhlAPa variants demonstrated increased RL production during the whole fermentation period relative to the strain carrying WT RhlAPa (Figure 10). Overexpression of variants Q69N, R202K, and T227S led to strains producing up to 700 mg/L RLs, while the Y165F variant reached the maximum value recorded in this study, i.e. 800 mg/L RL production. This variant showed 100% increased yield relative to PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7 complemented with WT RhlAPa, further confirming the rate-limiting function of RhlAPa in bacterial RL biosynthesis.

Figure 10.

Kinetics of rhamnolipid production for improved rhlA variants under the metabolic pressure of PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7. Experiments were performed for 72 h at 34 °C in MSM-glycerol broth. RL analysis includes all mono- and di-RLs detected by LC/MS.

Combinatorial amino acid substitutions.

To investigate cooperativity between important positions near the modeled active site of RhlAPa (Figure 8B), we combined favorable point mutations with the aim to further enhance RL production. We found that the combination of active point mutants K164R, Y165F, and T227S did not provide significant increases in enzyme activity relative to WT RhlAPa (Table 5). Similarly, combining unfavorable and favorable mutations also further reduced the catalytic activity of RhlAPa (e.g. R141A-K164R and R141A-T161A-K164R). Unfortunately, the lack of a reliable high throughput screening method for the in vivo production of RLs currently precludes proper screening of large combinatorial or randomized RhlA mutant libraries. However, to experimentally validate whether the combination of our previously selected favorable residue positions is advantageous when permutations are combinatorially mutated with a broader range of amino acid replacements, we pursued the discrete random combination of the abovementioned RhlAPa variants with the theoretical generation of 197 mutants (Figure S4). We quantified RL production with the orcinol method, using the constitutive expression of the new RhlAPa variants in a PA14ΔrhlA background [59, 60]. Surprisingly, we found a remarkably lower RL production in RhlAPa variants relative to WT RhlAPa. Unexpectedly, mutational combinations at these positions produced deleterious effects in terms of RhlAPa activity. As a result, whether point mutants M37N, Q69N, K164R, Y165F, R169K, R202K, E224D, T227S, and D230E can cooperatively contribute to improving the catalytic efficiency of RhlAPa remains elusive.

DISCUSSION

RhlA catalyses the esterification of two hydroxylated fatty acid units to produce HAA, the lipid precursor of RLs [15, 30, 46] (Figure 1). This catalytic reaction represents a crucial step in RL biosynthesis, positioning RhlA as an interesting engineering target to increase precursor flux for the production of this biosurfactant. The catalytic role of RhlA in RL biosynthesis suggests that this enzyme modulates fatty acid chain length observed in different RL mixtures [15]. The importance of improving RL production and controlling RL alkyl chain length composition remains an important goal for the effective design of biosurfactants. The present work represents the first attempt at quantifying the relationship between the putative cap-domain and substrate selectivity in RhlAPa, illustrating how increased HAA biosynthesis impacts total RL production. We showed that RhlAPa is directly responsible for the diversity of alkyl chain lengths in RLs. Our cross-complementation assay (rhlAPa/rhlBPa operon expressed in BGR1ΔrhlA) confirmed the restricted selectivity of RhlAPa toward C8-C12 substrates within a metabolic background, providing C8-C16 hydroxyfatty acids (Figure 2). In contrast, RhlABg exhibited wider selectivity, adjusting its catalytic behavior to the environmental availability of the precursor (rhlABg/rhlBPa in PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7). Under this metabolic pressure, RhlABg can synthesize short chain RLs such as C8 and C12 (an outlier behavior for this enzyme), while still exhibiting clear preference for C14 and C12 substrates when the proper environmental availability is provided by the B. glumae strain (with glycerol as sole carbon source).

To overcome the lack of an experimental structure and to investigate potential structural elements involved in RhlAPa selectivity, we built a homology model of the enzyme and explored it using semi-rational single-site mutagenesis. It has been suggested that 30% sequence identity is a reliable cutoff to build trustworthy protein homology models [50]. Our best template exhibited 28.4% sequence identity and reliably predicted the canonical α/β hydrolase fold, in addition to predicting the catalytic triad of homologous experimental structures (Figure 4C). Despite the inherent limitations of this approach, we broadly used this model as structural guidance to perform experimental site directed mutagenesis and chimeric analysis of RhlAPa (Figures 4 and 8). Mutational analyses and alanine scanning investigation adequately identified the catalytic pocket of RhlAPa, localizing the S102, D223, and H251 catalytic residues within an enzyme core primarily formed by residues 132-210 and 221-227. Residues 132-210 are predicted to form five α-helices (αD1-αD5) of a putative cap-domain, a well-known structural feature providing substrate specificity within homologous α/β hydrolase family members [56, 61] (Figure 6A). Since RhlAPa and RhlABg clearly show distinct substrate selectivity, we also performed sectional swapping of the putative RhlABg cap-domain within the RhlAPa background, yielding chimeras RhlAH-1, RhlAH-2, and RhlAH-3 (Figure 6A). Expression of these chimeric enzymes in BGR1ΔrhlA yielded biosynthesis of two new RL mixtures, with a remarkably higher ratio of larger chain lengths in comparison with WT RhlAPa. While RhlAH-1 increased the incorporation of C12 over C10 hydroxyfatty acids into HAAs, RhlAH-2 and RhlAH-3 exhibited increased incorporation of C12 over C14 substrates (Figure 6B). These results demonstrate the involvement of C-terminal residues 132-190 in RhlA substrate selectivity.

The fact that this specific region modulates substrate selectivity illustrates its direct role in providing the active site of RhlA with an adequate physicochemical environment for optimal catalysis. Lid swapping has been reported as an effective approach to modify substrate specificity and enantioselectivity in lipases [36–41]. Hence, the abundant diversity of RhlAs producing a range of different congeners showcases the importance of targeting this region as a source of designed RhlA variants to produce new HAA/RL mixtures and/or pure HAA or RL congeners.

In our attempt to identify positions that promote the biocatalytic activity of RhlAPa, we uncovered interesting amino acid replacements located in the vicinity of the active site (Figure 4A). Except for E224, mutated residues located in this specific region significantly affected catalytic activity upon substitution by alanine (Table 5). Specifically, Arg and Tyr replacements at positions 164 and 165 play critical roles in enzyme activity due to their significant decrease in HAA and RL production. Interestingly, substitutions K164R, Y165F, and E224D showed an increase in RL production up to ≈90% (Figure 8C and Table 5), with the most significant increase resulting from the loss of a polar terminal hydroxyl group in variant Y165F. The additive behavior of mutations was also tested by combining negative and positive substitutions. The negative effect of variant R141A on catalysis (≈37% depletion in rhamnolipid production) was nearly recovered to WT levels after introduction of mutation K164R (see double mutant R141A/K164R, Table 5). In contrast, complete loss of RhlAPa activity was observed after addition of a second negative mutation in the context of this double variant (see triple mutant R141A/T161A/K164R). Future structural studies will be required to investigate whether beneficial mutations (e.g. K164R and E224D on the putative αD1-αD2 helices) favor rhamnolipid synthesis due to protein/substrate stabilization and/or promoting access to the active-site pocket (Figure 8B).

It is also possible that selected mutations in the active-site channels could perturb their shape and volume, in addition to affecting conformational dynamics of the cap-domain, which we have shown to be possible by performing normal mode analysis (NMA) (Figure 11). Such conformational exchange could also create new access channels to the active site within the cap-domain. Likewise, we cannot exclude the possibility that positive surface substitutions (e.g. at positions 164, 169, 224, 227 and 230) could be involved in protein (de)stabilization, recognition of acyl carrier protein (ACP), and ACP-RhlA complex formation, which provides hydroxylated fatty acids to RhlA during HAA synthesis [15]. Overall, we do expect the cap-domain of RhlA to play an integral part in safeguarding specificity and/or optimal catalytic efficiency in RhlA, much like the cap-domain of other α/β hydrolases was shown to be essential for enzyme activity.

Figure 11.

Conformational exchange of the putative cap-domain in RhlA. A) Conformational dynamics modeled by Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) of the minimized RhlA model structure using elNémo [77]. B) Effects of cap-domain dynamics on access channel shape and orientation. Nine conformational states are showed. Channel surfaces and cavities are shown in yellow and the cap-domain is colored blue. Access channels are numbered as in Figure 8 and the formation of new channels is labeled by letter N. Only open channels are shown.

Mutagenesis exploration of the active-site environment revealed that all 29 substitutions severely reduced rhamnolipid synthesis in RhlAPa, except for two mutations at positions 37 and 224 (Figure 4B). This alanine scanning and selective mutagenesis replacement (i.e. amino acid replacements with similar physicochemical features) confirm the importance of these residue positions in maintaining the synthetic ability of RhlAPa. In contrast, the M37L replacement increased the catalytic activity of RhlAPa. Interestingly, this favorable leucine substitution in RhlAPa occurs at a normally conserved leucine position in functional homologs, whereby the only exception is the methionine residue found among Pseudomonas RhlA members (Figure 7). This observation suggests a specific role for this methionine in the Pseudomonas genus. It is worth mentioning that 7 of the best 8 mutations that increase the synthetic activity of RhlAPa are located in the vicinity of potential molecular channels connecting the active-site cavity to the protein surface (Figure 8B). Mutagenesis at these positions yielded favorable effects on RhlAPa catalysis, with most replacements (Y165F, R169K, R202K, E224D, and T227S) exhibiting similar physicochemical features and smaller side-chain changes (i.e. polar substitutions, except at position 165). These results suggest that lower side-chain size could increase active-site volume and access, further promoting substrate transit and improved catalytic activity.

α/β hydrolase homology and careful RhlA model analysis predict that the main active-site cavity can only accommodate one substrate unit at a time, in apparent contradiction with the fact that RhlA catalyzes the esterification of two substrate molecules to produce HAA. Consequently, it is highly probable that the cap-domain either experiences conformational exchange and/or relies on the existence of extra channels to accommodate the two additional substrate units required to synthesize HAA (Figure 11). This hypothesis is in accordance with the previously reported sequential mechanism for HAA synthesis, whereby smaller fatty acid molecules enter the active-site cavity first, followed by sequential addition of a second larger substrate molecule [62]. As a result, catalytic activity could be favored by minor conformational adjustments resulting from mutations R169K, R202K, T227S, and D230E, which are localized far from the active-site pocket, but in the predicted cap-domain vicinity.

Although the lack of an experimentally resolved RhlAPa structure currently precludes confirmation of these modeled observations, our comprehensive mutational exploration of the RhlA structure strongly positions the putative cap-domain motif as an important functional and engineering ‘hot spot’ to modulate the catalytic activity of this enzyme. Similarly, the role of αD3-αD4 helices on RhlAPa selectivity favors this region as one of the most promising targets for future studies aimed at the development of RhlAPa variants with improved substrate selectivity. Ongoing structural, biophysical, and functional studies on the most relevant RhlAPa variants will provide additional information on the relative importance of selected mutations in expression, stability, and/or activity in this enzyme. Overall, the molecular investigation of RhlAPa variants will likely offer better tools to engineer the biosynthesis of new rhamnolipid mixtures exhibiting promising biosurfactant properties.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Homology modeling of RhlAPa.

PSI-Blast and HHblits algorithms were used to identify the best structural template candidates for homology modeling with the RhlAPa target [47, 48], i.e. template structures of proline iminopeptidase-related protein TTHA1809 (PDB entry 2YYS), amidohydrolase VinJ (PDB entry 3WMR), and α/β hydrolase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (PDB entry 3OM8). T-Coffee Expresso was used to evaluate the local reliability of the templates found by PSI-BLAST and HHblits [63]. Homology modeling outputs of three individual servers were compared: Robetta [64–66], SWISS-MODEL [67, 68], and I-Tasser [53, 69]. PDB templates 2YYS (chain A), 3WMR (chain A), and 3OM8 (chain A) were used for Robetta, SWISS-MODEL, and I-Tasser, respectively. The best computed models for each server were independently ranked and selected by their own scoring functions for further validation. Additional model validation included evaluation of the best atomic solvation and molecular packing by SolVX [70], structural validation by Cα carbon geometry (RAMPAGE [71]), statistical error evaluation by model regions calculated based on non-bonded interactions between different atom types relative to a curated database of highly refined structures (ERRAT [72]), determination of model compatibility with its own residue sequence based on local environment (VERIFY_3D [73]), stereochemical quality of the protein structure (PROCHECK [74]), energy validation of model packing quality (ANOLEA [75]), biomolecular molecular dynamics simulations (GROMOS [76]), and composite scoring function for homology model quality estimation (QMEAN [51]). RhlAPa homology model selection and validation is summarized in Table 2 and Figure S1.

Normal Mode Analysis.

To simulate conformational dynamics in RhlA, the best Robetta model was used as input structure to calculate the elastic network provided by the server elNémo [77]. Ten models of the lowest-frequency normal modes were computed, with minimal and maximum perturbation range of −100. Elastic interactions cutoff was fixed at 8 Å. RMSD values and residues were automatically grouped according to default parameters. The best elastic network model was manually selected based on best frequency and collectivity scores.

Selection of target residue positions and structural exploration of the RhlA mutants.

To identify potential ligand binding sites corresponding to common substrates of the α/β hydrolase fold, a combination of TM-align and COACH tools were employed to scan the closest protein structures in the Protein Data Bank [54, 57]. The RosettaBackrub server was employed to predict backbone effects upon mutagenesis of RhlAPa [78, 79]. The Computed Atlas of Surface Topography of proteins was used to calculate the concomitant modifications of surfaces and cavities after mutagenesis of the RhlAPa homology model [80]. The CHEXVIS tool was applied to the molecular channel extraction of the cap-domain using a PyMOL plugin to analyze results and generate images in Figure 8B [81]. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC) and USCF Chimera 1.1 were used for all analyses and molecular structure visualization performed in this work. Carton models were created using the Pro-origami package and the motif topology search was obtained from the SA tableau tool [82, 83].

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth media.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 6 and S1. For molecular biology experiments, lysogeny broth (LB) was used for all cultures. Bacteria were grown at 37°C in a TC-7 roller drum (New Brunswick) or on LB agar plates. For RL production experiments on P. aeruginosa, MSM-glycerol broth was used [84]. Composition of MSM-glycerol broth is 15 g/L glycerol, 0.9 g/L Na2HPO4, 0.7 g/L KH2PO4, 0.1 g/L CaCl2•2H2O, 0.4 g/L MgSO4•7H2O, 2 g/L NaNO3, 2 mL/L trace element solution (TES), pH 7 ± 0.1. Composition of TES is 2 g/L FeSO4•7H2O, 1.5 g/L MnSO4•H2O, 0.6 g/L (NH4)6Mo7O24•4H2O). Bacteria were grown at 34°C in TC-7. For RL production experiments on B. glumae, cultures were performed on nutrient broth (NB; Difco™) supplemented with 20 g/L mannitol.

Table 6.

Bacterial strains used in this study.

| Strains | Characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa PA14 | Clinical isolate UCBPP-PA14 | [89] |

| PA14_ rhlA::MrT7− | Inactivation of rhlA in PA14 (rhlA::MrT7) (polar mutant) | [90] |

| B. glumae BGR1 | Wild-type, RifR | [91] |

| B. glumae BGR1 rhlA− | Deletion of rhlA in BGR1 (polar mutant) | [92] |

| E. coli DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (Φ80lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | Invitrogen |

| E. coli 5-alpha | DH5α derivate. fhuA2 Δ(argF-lacZ)U169 phoA glnV44 Φ80 Δ(lacZ)M15 gyrA96 recA1 relA1 endA1 thi-1 hsdR17 | NEB |

Rhamnolipid production in P. aeruginosa.

To test the production of RLs in P. aeruginosa, at least three positive clones of each strain or mutant were grown overnight at 37°C with shaking in 5 mL LB broth, with addition of antibiotics, as needed. Overnight pre-cultures were washed once with sterile PBS and once with MSM broth. Cultures were carried out in 5 mL MSM-glycerol broth starting at an initial OD600 = 0.1, or in 50 mL for kinetic characterization. Appropriate antibiotics were included as needed. Cultures were carried out at 34°C with shaking for ~75 h. Supernatants were prepared for LC/MS analysis by adding an equal volume of methanol supplemented with 10 mg/L 5,6,7,8-tetradeutero-4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinolone (HHQd4) and 50 mg/L 16-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid as internal standards. Supernatants were then collected by centrifugation at 10,000g for 15 minutes. RLs were analyzed and quantified by LC/MS (see below).

Rhamnolipid production in B. glumae.

Rhamnolipid production in B. glumae followed the P. aeruginosa procedure described above, with the following modifications. Cultures were carried out in NB-mannitol broth supplemented with antibiotic, as needed. The initial OD600 was 0.05 and cultures were carried out at 37°C with shaking for ~120 h. The internal standards HHQd4 and 16-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid were added to 3.5 mL culture supernatant and the solution acidified to pH 2 with 150 μL 12 N HCl. RLs were then extracted three times with 1 mL ethyl acetate. The organic fractions were pooled, evaporated to dryness and the dry extract was finally resuspended in 350 μl MS negative buffer (30% acetonitrile, 1 % acetic acid). Samples were finally filtered with a 0.2 μm pore size PTFE filter membrane (Sigma-Aldrich) and analyzed by LC/MS.

Site-directed mutagenesis of rhlAPa.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the rhlAPa gene was performed using plasmid pAS25 (Table S1) as template and following either a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis procedure [85] or a SPPCR protocol [86] to yield plasmid pAS25M. Primers were generated using the QuikChange primer design tool of Agilent Technologies [87]. For QuikChange mutagenesis, PCR was carried out using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher), while Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB) was used for SPPCR. rhlA-mutated genes were confirmed by DNA sequencing. rhlA-mutated fragments of pAS25M were digested by EcoRI and HindIII, respectively, and inserted into the same sites of the multicopy plasmid pUCP26 to yield pAS23M.

Quantification of free intracellular 3-hydroxyfatty acids in P. aeruginosa.

The free intracellular 3-hydroxyfatty acid pool of P. aeruginosa PA14 in early stationary growth phase was analyzed by GC/MS. To reduce interference from RLs and HAAs, which require additional hydrolysis steps, we performed the experiment with a PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7 mutant. The selected strain was cultivated as described for RL production, in MSM-glycerol broth medium at 34°C for 72 h at 300 rpm. Cells were recovered by centrifugation (4,400g, 10 min) from 10 mL culture. The pellet was resuspended in 1 mL PBS and the internal standard methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate was added at a final concentration of 20 ppm. Cells were then lysed by sonication and the lysate was acidified to pH 2 with 12 N HCl. 3-hydroxyfatty acids were then extracted three times with 2 mL ethyl acetate. The organic phases were combined and evaporated to dryness under a stream of nitrogen gas, then resuspended in 1 mL ethyl acetate and dehydrated by adding Na2SO4. A sample of 100 μL was prepared for silylation by adding 30 μL BSTFA and 90 μL acetonitrile, then incubated overnight at 70°C. The sample was diluted with acetonitrile to a volume of 1 mL prior to injection into the gas chromatograph. The GC/MS analytical method was performed using a Trace GC Ultra - Polaris Q (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) equipped with a ZB-5MS (ZebronTM) capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm internal diameter, 0.25 μM film thickness, Phenomenex®) using the electron impact ionization mode. The GC program used an oven temperature of 70°C held for 5 min, then increased at a rate of 20°C/min to reach 140°C, then increased at a rate of 30°C/min to reach 160°C, then increased at a rate of 40°C/min to reach 310°C, which was held for 3 min with an overall oven run time of 15.92 min. The sample injection volume was 1 μL. The mass spectrometer (Polaris Q) was operated in full scan positive ion mode covering the mass range of 70-600 with a total scan time of 0.54 second. MS scan started at 6.6 min and the ion source temperature was set at 250 °C. The injector and detector (ion source) temperatures were both set at 250 °C. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1.1 ml/min. Quantification was performed by comparing integration data of M•+ fragment ions resulting from the electron impact of the trimethylsilyl esters of 3-hydroxyfatty acids with those of the 3-hydroxyalkanoic acid standards prepared and analyzed using the same procedure. Free C8, C10, C12 and C14 hydroxyfatty acids were detected with m/z=304.2 at 10:54 min, m/z=322.2 at 11:23 min, m/z=360.3 at 11:80 min, and m/z=388.2 at 12:31 min, respectively. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Error bars were calculated from standard deviation of three independent measurements (n = 3).

Construction of the rhlAPa/rhlBPa hybrid operon.

To express the rhlABg gene within the polar mutant PA14_rhlA::TnMrT7, the rhlABg gene was swapped in the rhlAPa/rhlBPa wild-type operon of plasmid pAS23. Three PCR fragments were generated (Tables 6–S1, Figure S3). Fragments 1 and 3 (bases −90 to −1 of rhlAPa and −65 to 1346 of rhlBPa, respectively) were obtained by PCR from the genomic DNA of PA14 using primers P-EcoRI-F/P1-90-R and P3-65-F/P-HindIII-R, respectively. Fragment 2, which corresponds to the rhlABg coding sequence, was PCR-amplified from the genomic DNA of BGR1 as template and primers P2-rhlABg-F/P2-rhlABg-R. These three PCR amplicons were purified using a DNA gel extraction kit (Bio Basic) and fused together by overlap extension PCR and primers P-EcoRI-F/P-HindIII-R. The PCR product obtained was purified and sequentially digested with EcoRI and HindIII (Thermo Fisher). In parallel, pAS23 (carrying the wild-type operon rhlAPa/rhlBPa) was digested and purified using similar conditions. Ligation was carried out with the T4 DNA ligase (NEB) and transformation was performed in chemically competent E. coli DH5α cells. The chimeric operon was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The functional expression of rhlABg/rhlBPa was confirmed by complementation of a polar BGR1ΔrhlA mutant and RL detection by LC/MS.

Construction of chimeric rhlA genes.

Three chimeric rhlA genes were built by swapping bases 397-495, 397-597, and 397-630 of rhlABg in rhlAPa. Chimeric fragments 2, 3, and 4 (bases 397-495, 397-597 and 397-630, respectively) were generated by PCR amplification from genomic rhlABg using primers P234F/P2R, P234F/P3R, and P234F/P4R, respectively. Upstream fragment 1 (bases −90-396) and downstream fragments 5, 6, and 7 (bases 496-789, 598-789 and 631-789, respectively) were obtained by PCR amplification from genomic rhlAPa using primers P-EcoRI-F/P1R, P5F/P-SacII-R, P6F/P-SacII-R, and P7F/P-SacII-R, respectively. Chimeric genes rhlAPa-H1, rhlAPa-H2, and rhlAPa-H3 were obtained by overlap extension PCR with fragments 1-2-5, 1-3-6, and 1-4-7, respectively, using primers P-EcoRI-F/P-SacII-R. Finally, chimeric rhlA genes were digested with EcoRI and SacII prior to cloning into plasmid pAS23, yielding plasmids pCD6, pCD7, and pCD8, respectively (Tables S1 and S2, Figure S2). Chimeric rhlA genes were confirmed by DNA sequencing. All amplicons were generated using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher).

Randomized combinations of selected RhlAPa amino acid substitutions.

Single rhlA variants M37L, Q69N, K164R, Y165F, R169K, R202K, E224D, T227S, D230E, and double variants K164R/Y165F, K164R/T227S, and Y165F/T227S were used as template to generate 7 rhlA fragment groups that were randomly recombined and assembled with fragment 1 using the Gibson assembly cloning kit (NEB) (Figure S4). Fragment 1 corresponds to linear plasmid pAS29 (pET28a-rhlABPA14) obtained by PCR amplification using Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB) with primers PG1F/PG1R. Transformed E. coli cells were selected on LB agar plates containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin. Randomized mutational combinations were verified by sequencing the rhlA-combined genes from 20 clones. Clones were picked from a Petri dish colony growth and collected cells were used for standard miniprep DNA extraction (BioBasic). rhlA-recombined variants were then subcloned into constitutive expression vector pUCP26 using XbaI and HindIII restriction sites to yield plasmids pCD9M, which were finally transformed into a PA14ΔrhlA mutant. Quantification of in vivo RL production was performed using the orcinol spectrophotometric assay [59].

RL quantification based on the orcinol assay.

RL quantification was also performed using the orcinol assay, whereby RLs were extracted three times from a 5-mL culture (acidified with 200 μL HCl 12 N) with 1 mL ethyl acetate. Samples were mixed by vortexing, with subsequent phase separation by centrifugation. The organic phase was evaporated to dryness and the dry extract was then resuspended in 100 μL H2O, to which 100 μL orcinol solution (1.6% orcinol in H2O) and 800 μL H2SO4 (60%) were added prior to incubation at 80°C for 30 min. Samples developed a blue-green color that was measured spectrophotometrically at 421 nm [59]. A standard curve was prepared with rhamnose for quantification and a correction factor of 2.25 was applied to compensate for the extra mass of the RL lipidic portion [46].

Detection and quantification of HAAs and RLs by LC/MS.

LC/MS analyses were performed on a Waters system composed of a triple quadrupole Quattro Premier XE interfaced to a Waters 2795 HPLC (Waters, Mississauga, ON). Samples were separated on a Phenomenex Luna Omega PS C18 column (100 × 3 mm, 5 μm) under isocratic conditions with a mobile phase composed of water and acetonitrile containing 1% acetic acid. Quantification of various HAA and rhamnolipids was performed using HHQ-d4 as internal standard, as described previously [88]. The mass spectrometer was operated in negative electrospray ionization mode with a capillary voltage of 5 kV and a cone voltage of 30 V. Nitrogen was the nebulizer gas and the source was held at 120 °C. Scanning was performed in full scan mode with a mass range of 130 to 930 m/z. In negative mode, 2 mM ammonium acetate was included in the water and acetonitrile mobile phases. Fatty acid contribution within congeners were calculated from detected pseudomolecular ions [(C8-C8)-H]− (m/z 301.3), [(Rha-C8-C8)-H]− (m/z 447.3), [(Rha-Rha-C8-C8)-H]− (m/z 593.5), [(C8-C10)-H]−/ [(C10-C8)-H]− (m/z 329.3), [(Rha-C8-C10)-H]−/[(Rha-C10-C8)-H]− (m/z 475.4), [(Rha-Rha-C8-C10)-H]−/[(Rha-Rha-C10-C8)-H]− (m/z 621.6), [(C10-C10)-H]− (m/z 357.3), [(Rha-C10-C10)-H]− (m/z 503.4), [(Rha-Rha-C10-C10)-H]− (m/z 649.5), [(C10-C12/C12-C10)-H]− (m/z 385.3), [(Rha-C10-C12)-H]−/Rha-C12-C10)-H]− (m/z 531.4), [(Rha-Rha-C10-C12)-H]−/[(Rha-Rha-C12-C10)-H]− (m/z 677.5), [(C12-C12)-H]− (m/z 413.6), [(Rha-C12-C12)-H]− (m/z 559.7), [(Rha-Rha-C12-C12)-H]− (m/z 705.5), [(C12-C14)-H]−/ [(C14-C12)-H]− (m/z 441.4), [(Rha-C12-C14)-H]−/[(Rha-C14-C12)-H]− (m/z 587.4), [(Rha-Rha-C12-C14)-H]−/[(Rha-Rha-C14-C12)-H]− (m/z 733.5), [(C14-C14)-H]− (m/z 469.4), [(Rha-C14-C14)-H]− (m/z 615.5), [(Rha-Rha-C14-C14)-H]− (m/z 761.6), [(C14-C16)-H]−/ [(C16-C14)-H]− (m/z 497.4), [(Rha-C14-C16)-H]−/[(Rha-C16-C14)-H]− (m/z 643.5), [(Rha-Rha-C14-C16)-H]−/[(Rha-Rha-C16-C14)-H]− (m/z 789.6), [(C16-C16)-H]− (m/z 525.4), [(Rha-C16-C16)-H]− (m/z 671.5) and [(Rha-Rha-C16-C16)-H]− (m/z 817.6).

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Plasmids used in this study.

Table S2. Primers used in this study.

Figure S1. Second validation round of the best ranking homology models of RhlAPa.

Figure S2. Strategy for construction of rhlAPa-H-1, rhlAPa-H-2, and rhlAPa-H-3 chimeric genes.

Figure S3. Strategy for construction of the rhlABg/rhlBPa hybrid operon.

Figure S4. Strategy for random combination of selected rhlAPa amino acid substitutions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Marie-Christine Groleau, Sylvain Milot and Andrés M. Rueda for helpful technical assistance and discussions. This work was supported in part by Discovery grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) under award numbers RGPIN-2016-05557 (to ND) and RGPIN-2015-03931 (to ED), in addition to a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award R01GM105978 (to ND). CED was the recipient of PhD scholarships from the Fondation Armand-Frappier, the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Nature et technologies (FRQNT), the Regroupement québécois de recherche sur la fonction, l’ingénierie et les applications des protéines (PROTEO), and the Groupe de recherche axé sur la structure des protéines (GRASP). YLS held a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Merit Scholarship Program for Foreign Students of the Ministère de l’éducation, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche du Québec (File number 194706). ED holds a Canada Research Chair (CRC) in sociomicrobiology, and ND is the recipient of a Fonds de Recherche Québec – Santé (FRQS) Research Scholar Junior 2 Career Award (number 32743).

Abbreviations:

- HAA

3-(3-hydroxyalkanoyloxy)alkanoate

- RL

rhamnolipid

- ACP

acyl carrier protein

- RhlAPa

RhlA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- RhlABg

RhlA from Burkholderia glumae

- RT-PCR

reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- NMA

normal mode analysis

Footnotes

Database: Model data are available in the PMDB database under the accession number PM0081867.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdel-Mawgoud AM, Aboulwafa MM & Hassouna NA (2009) Characterization of rhamnolipid produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate Bs20, Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 157, 329–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdel-Mawgoud AM, Lépine F & Déziel E (2010) Rhamnolipids: diversity of structures, microbial origins and roles, Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 86, 1323–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vatsa P, Sanchez L, Clement C, Baillieul F & Dorey S (2010) Rhamnolipid biosurfactants as new players in animal and plant defense against microbes, Int J Mol Sci. 11, 5095–5108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeSanto K (2011) Rhamnolipid mechanism. US Patent 201,101,236,23 A1, US Patent 201,101,236,23 A1.

- 5.Parry AJ, Parry NJ, Peilow C & Stevenson PS (2013) Combinations of rhamnolipids and enzymes for improved cleaning, Patent No EP 2596087A1.

- 6.Sachdev DP & Cameotra SS (2013) Biosurfactants in agriculture, Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 97, 1005–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piljac A, Stipcevic T, Piljac-Zegarac J & Piljac G (2008) Successful treatment of chronic decubitus ulcer with 0.1% dirhamnolipid ointment, J Cutan Med Surg. 12, 142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y & Miller RM (1992) Enhanced octadecane dispersion and biodegradation by a Pseudomonas rhamnolipid surfactant (biosurfactant), Appl Environ Microbiol. 58, 3276–3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Q, Bao M, Fan X, Liang S & Sun P (2013) Rhamnolipids enhance marine oil spill bioremediation in laboratory system, Mar Pollut Bull. 71, 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chrzanowski L, Dziadas M, Lawniczak L, Cyplik P, Bialas W, Szulc A, Lisiecki P & Jelen H (2012) Biodegradation of rhamnolipids in liquid cultures: effect of biosurfactant dissipation on diesel fuel/B20 blend biodegradation efficiency and bacterial community composition, Bioresour Technol. 111, 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergström S, Theorell H & Davide H (1946) Pyolipic acid. A metabolic product of Pseudomonas pyocyanea active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis., Arch Biochem Biophys. 10, 165–166. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarvis FG & Johnson MJ (1949) A glyco-lipid produced by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, J Am Chem Soc. 71, 4124–4126. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Déziel E, Lépine F, Milot S & Villemur R (2003) rhlA is required for the production of a novel biosurfactant promoting swarming motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: 3-(3-hydroxyalkanoyloxy)alkanoic acids (HAAs), the precursors of rhamnolipids, Microbiology. 149, 2005–2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burger MM, Glaser L & Burton RM (1963) The enzymatic synthesis of a rhamnose-containing glycolipid by extracts of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, J Biol Chem. 238, 2595–2602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu K & Rock CO (2008) RhlA converts beta-hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein intermediates in fatty acid synthesis to the beta-hydroxydecanoyl-beta-hydroxydecanoate component of rhamnolipids in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, J Bacteriol. 190, 3147–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ochsner UA, Reiser J, Fiechter A & Witholt B (1995) Production of Pseudomonas aeruginosa rhamnolipid biosurfactants in heterologous hosts, Appl Environ Microbiol. 61, 3503–3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards JR & Hayashi JA (1965) Structure of a rhamnolipid from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Arch Biochem Biophys. 111, 415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahim R, Ochsner UA, Olvera C, Graninger M, Messner P, Lam JS & Soberon-Chavez G (2001) Cloning and functional characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa rhlC gene that encodes rhamnosyltransferase 2, an enzyme responsible for di-rhamnolipid biosynthesis, Mol Microbiol. 40, 708–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahim R, Burrows LL, Monteiro MA, Perry MB & Lam JS (2000) Involvement of the rml locus in core oligosaccharide and O polysaccharide assembly in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Microbiology. 146, 2803–2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdel-Mawgoud AM, Lépine F & Déziel E (2014) A stereospecific pathway diverts beta-oxidation intermediates to the biosynthesis of rhamnolipid biosurfactants, Chem Biol. 21, 156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Veres-Schalnat TA, Somogyi A, Pemberton JE & Maier RM (2012) Fatty acid cosubstrates provide beta-oxidation precursors for rhamnolipid biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, as evidenced by isotope tracing and gene expression assays, Appl Environ Microbiol. 78, 8611–8622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendes A, Filgueiras L, Pinto J & Nele M (2015) Physicochemical properties of rhamnolipid biosurfactant from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA1 to applications in microemulsions, J Biomater Nanobiotechnol. 6, 64–79. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiso T, Zauter R, Tulke H, Leuchtle B, Li WJ, Behrens B, Wittgens A, Rosenau F, Hayen H & Blank LM (2017) Designer rhamnolipids by reduction of congener diversity: production and characterization, Microb Cell Fact. 16, 225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Randhawa KKS & Rahman PKSM (2014) Rhamnolipid biosurfactants, past, present, and future scenario of global market, Front Microbiol. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovaglio RB, Silva VL, Ferreira H, Hausmann R & Contiero J (2015) Rhamnolipids know-how: Looking for strategies for its industrial dissemination, Biotechnol Adv. 33, 1715–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchant R & Banat IM (2012) Microbial biosurfactants: challenges and opportunities for future exploitation, Trends Biotechnol. 30, 558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han L, Liu P, Peng Y, Lin J, Wang Q & Ma Y (2014) Engineering the biosynthesis of novel rhamnolipids in Escherichia coli for enhanced oil recovery, J Appl Microbiol. 117, 139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]