Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the potential impact of intrapartum antibiotics, and their specific classes, on the infant gut microbiota in the first year of life.

Design

Prospective study of infants in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study (NHBCS).

Settings

Rural New Hampshire, USA.

Population or sample

Two hundred and sixty-six full-term infants from the NHBCS.

Methods

Intrapartum antibiotic use during labour and delivery was abstracted from medical records. Faecal samples collected at 6 weeks and 1 year of age were characterised by 16S rRNA sequencing, and metagenomics analysis in a subset of samples.

Exposures

Maternal exposure to antibiotics during labour and delivery.

Main outcome measure

Taxonomic and functional profiles of faecal samples.

Results

Infant exposure to intrapartum antibiotics, particularly to two or more antibiotic classes, was independently associated with lower microbial diversity scores as well as a unique bacterial community at 6 weeks (GUnifrac, P = 0.02). At 1 year, infants in the penicillin-only group had significantly lower α diversity scores than infants not exposed to intrapartum antibiotics. Within the first year of life, intrapartum exposure to penicillins was related to a significantly lower increase in several taxa including Bacteroides, use of cephalosporins was associated with a significantly lower rise over time in Bifidobacterium and infants in the multi-class group experienced a significantly higher increase in Veillonella dispar.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that intrapartum antibiotics alter the developmental trajectory of the infant gut microbiome, and specific antibiotic types may impact community composition, diversity and keystone immune training taxa.

Keywords: Gut, infant, intestinal microbiota, intrapartum antibiotics, neonate

Tweetable abstract

Class of intrapartum antibiotics administered during delivery relates to maturation of infant gut microbiota.

Introduction

As we begin to understand the important contributions of the developing microbiome to health, fundamental questions about the relationship of antibiotics to dysbiosis, and ultimate health effects, are being raised.1 A shift from a pathogen-dominated perspective of microbes to a focus on the beneficial aspects of the microbiota and its role in developing competent immune function has highlighted the importance of microbiome development.2,3 In particular, the impact of antibiotics in the critical window of an infant’s early life, during which microbes play a seminal role in immune training, is a major knowledge gap. Accumulating evidence shows that the establishment of the microbiome during this vulnerable developmental period fundamentally influences disease risk later in life.4,5 The Centers for Disease Control estimates that 20% of pregnant women are exposed to antibiotics before delivery, while 50% are exposed during the processes of labour and delivery in accordance with protocols for caesarean section, intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis against Group B streptococcus (GBS) colonisation and suspected intrauterine infection/chorioamnionitis.6

Acquisition of the microbiome in infancy is required for competent immune maturation.7–9 In healthy neonatal populations, colonisation may begin during fetal life,10–12 with a substantial introduction of microbes during the process of delivery,13–16 and in early infancy.17–20 Emerging data indicate that exposure to antibiotics during early infancy leads to persistent alterations in immune functions that are primarily implicated in the cause of allergic and atopic disease.21,22 Various clinical factors can necessitate the use of different classes of antibiotics, and it is increasingly evident that antibiotic-induced perturbation in the early microbiota may have profound consequences for later health.23,24 Clarifying the potential impact of specific antibiotic exposures in the perinatal, neonatal and infant period can highlight opportunities to alter these exposures, or identify interventions to alleviate the potential impact on the developing microbiome through diet, and altered antibiotic or probiotic regimens.

The objective of this study was to examine the relationship between intrapartum exposure to different classes of antibiotics and the developing infant intestinal microbiome in the first year of life within the prospective New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study (NHBCS).

Methods

Study population and design

Study participants were enrolled within the NHBCS, which is an ongoing birth cohort enrolling pregnant women aged 18–45 years at approximately 24 weeks of gestation.25,26 There was no participant engagement in the development of this study. Institutional review board approval was obtained at Dartmouth with yearly renewal. Participants provided written consent during pregnancy, and for their infant’s participation. Faecal samples from infants were collected prospectively at 6 weeks and 1 year of age. We restricted our analyses to infants who were vaginally delivered at full-term (>37 weeks of gestation) with available labour and delivery records. Infant diet was obtained throughout the first year of life from an interval telephone interview every 4 months that included questions regarding the duration of breastfeeding (where applicable) and the timing of formula and solid food introduction. Appendix S1 (see Supplementary material) includes additional details regarding infant feeding classification.

Data regarding all medications administered during labour and delivery were collected from maternal medical delivery records. Maternal antibiotic use was categorised into the following groups: (i) no antibiotics, (ii) penicillin-like only (amoxicillin, penicillin), (iii) cephalosporins only (cefazolin, cephalexin), (iv) multi-drug classes (involving two or more drugs under the category of penicillin, cephalosporin, vancomycin, clindamycin and/or gentamicin), and (v) other classes (aminoglycosides, glycopeptides or lincomycin only). This information, as well as additional variables including prenatal antibiotic and infant antibiotic exposure were derived from maternal medical records, interval telephone interviews and from neonatal hospital records for the period after delivery. Based on data from periodically administered questionnaires, infants with reported systemic (oral, injected or intravenous) administration of antibiotics were categorised as being exposed to systemic antibiotics in the first year of life.

Sample collection, processing and sequencing of 16S rRNA gene

Infant stool samples were collected at home by direct void into diapers which were wrap-folded, immediately frozen and subsequently brought to regularly scheduled maternal postnatal follow-up visits at 6 weeks postpartum and at the annual well-child visit. Frozen stool was thawed, split into aliquots using sterile swab and wood depressors and stored in RNAlater stabilising solution at −80°C. DNA was extracted using the ZR Fecal DNA MiniPrep™ kits (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA; D6010, 0.5 mm Bashing Bead Lysis Tubes). Quantity of DNA was determined by OD260/280 nanodrop or Qubit measurement. Positive reference stool controls and blank RNAlater negative controls were extracted and quantified to assess consistency and purity of yields. To further assess processing procedures for background microbiota contamination, a subset of negative controls was referred for 16S amplicon sequencing, but all negative controls failed to produce any amplicons in study-sequencing protocols.

16S rDNA V4–V5 amplicons were generated from these purified genomic DNA samples using fusion primers and sequenced at the Marine Biological Laboratory (Woods Hole, MA, USA), using established and previously described methods.27,28 More details on the amplification and sequencing protocol can be found in the Supplementary material (Appendix S1). The resulting trimmed and quality-filtered sequences were stored and subsequently retrieved from the Visualization and Analysis of Microbial Population Structures (VAMPS) website (http://vamps2.mbl.edu) for downstream analyses.29

Bioinformatics pipeline and statistical analysis

Sequence processing and analyses were performed in R v.3.4.1 (http://www.R-project.org) using the DADA2 sequence processing pipeline (v.1.6.0)30 to infer the amplicon sequence variants present and their relative abundances across samples. Thereafter, taxonomic assignment was performed on amplicon sequence variants using the Green-genes classifier and reference data set.31 Within the phyloseq package,32 amplicon sequence variant abundances were used to calculate α diversity indices. To determine statistical significance of the difference in α diversity indices between groups, F tests, Student’s t tests and linear regression analyses were performed. Using a midpoint-rooted phylogenetic tree generated from phangorn (v.2.4.0), overall community differences between samples (β diversity) were tested within vegan (v.2.4.6) by permutational multivariate analysis of variance of pairwise generalised UniFrac distance matrices, with 1000 permutations. To identify taxa that had a significant change over time based on the types of intrapartum antibiotic exposure, we employed a marginalised zero-inflated logistic normal (MZILN) model.33 This regression model does not require imputation of zero sequencing counts with a pseudo count and can handle compositional structure and inter-taxa correlation. The model adjusted for time of sample collection, antibiotic use in pregnancy and infancy, feeding mode at the time of sample collection and time of solid food introduction. A regularisation approach – minimax concave penalty34 – was incorporated into the analysis to deal with high dimensionality.

Processing and analysis of metagenomic samples

Metagenomic sequencing libraries were prepared at the Marine Biological Laboratory. Extracted DNA samples were sheared to a mean insert size of 400 bp using a Covaris S220 focused ultrasonicator. The sequencing libraries were constructed using Nugen’s Ovation Ultralow V2 protocol. Functional genomic profiles of the data set were generated using HUMAnN2 version 0.5.0. pipeline. Quality-filtered DNA reads were merged, trimmed with KNEAD/Trimmomatic and input in the HUMAnN2 pipeline under default parameters. With the resulting output for pathway abundances, we identified enriched and depleted pathways based on intrapartum antibiotic exposure using the STAMP software package35 with a false discovery rate adjusted P-value threshold of 0.10.

The study was funded by the US National Institutes for Health and US Environmental Protection Agency. The sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or in the writing of the report.

No core outcome set was used in this study.

Results

Study design and participants

Two hundred and sixty-six vaginally delivered mother–infant pairs enrolled in the NHBCS were included in the analysis.

The median (interquartile range) age – in days – of infants at sample collection were 44 (6.4) and 372 (25) for 6-week and 1-year samples, respectively. Table 1 shows the maternal and infant characteristics from the 266 mother–infant pairs stratified by intrapartum antibiotic exposure and type of antibiotic use. The majority of mothers were white and non-smokers. Mothers of 87 infants (33%) received antibiotics during labour or delivery. Neonates exposed to intrapartum antibiotics were more likely to have lower birthweight (P < 0.01) compared with those not exposed, GBS positivity (26%) was significantly different across the different antibiotic categories, and as expected, GBS positivity was markedly more strongly represented in the penicillin group compared with the unexposed group (91% versus 5%; P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population (n = 266)

| No antibiotics n = 179 |

Penicillina n = 55 |

Cephalosporinsb n = 14 |

Multi-classc n = 12 |

Othersd n = 6 |

P valuee | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | ||||||

| Age at delivery, years (SD) | 31.6 (4.4) | 32.5 (4.4) | 32.5 (3.0) | 31.0 (4.8) | 29.2 (6.6) | 0.35 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| White | 173 (97.8) | 54 (98.2) | 14 (100) | 12 (100) | 6 (100) | 0.85 |

| Other | 6 (2.2) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Parity (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 62 (35) | 23 (42.6) | 9 (64.3) | 7 (58.3) | 4 (66.7) | 0.17 |

| 1 | 79 (46) | 18 (33.3) | 5 (36.7) | 5 (41.7) | 1 (16.7) | |

| >2 | 35 (19) | 14 (26.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | |

| Prenatal antibiotics (%) | ||||||

| No | 154 (86) | 43 (78.2) | 11 (78.6) | 10 (83.3) | 6 (100) | 0.49 |

| Yes | 25 (14) | 12 (21.8) | 3 (21.4) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Group B streptococcus positive (%) | ||||||

| No | 176 (95.2) | 5 (9.1) | 13 (92.8) | 3 (36.1) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 3 (4.8) | 50 (90.9) | 1 (7.2) | 9 (63.9) | 6 (100) | |

| Child characteristics | ||||||

| Sex (%) | ||||||

| Male | 86 (48.8) | 33 (60) | 6 (42.8) | 9 (63.9) | 2 (33.3) | 0.18 |

| Female | 93 (51.2) | 22 (40) | 8 (57.1) | 3 (36.1) | 4 (66.6) | |

| Mean birthweight, g (SD) | 3556 (448) | 3370 (437) | 3365 (444) | 3415 (189) | 3244 (542) | 0.03 |

| Mean gestation, weeks (SD) | 39.5 (1.1) | 39.2 (1.2) | 39.0 (1.2) | 39.8 (1.1) | 39.6 (1.6) | 0.19 |

| Postpartum antibiotics (%) | ||||||

| No | 177 (98.9) | 53 (96.4) | 14 (100) | 12 (100) | 6 (100) | 0.54 |

| Yes | 2 (0.1) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

Includes amoxicillin, penicillin or ampicillin.

Includes cephalexin or cefazolin.

Includes a combination of two or more classes of antibiotics.

Includes aminoglycosides, glycopeptides or lincomycins.

One-way ANOVA test or chi-square test was performed where appropriate.

Bold text to highlight significant differences between groups (P < 0.05).

Infant intestinal microbial analysis

Illumina sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene V4–V5 hyper-variable regions yielded a total of 97 854 200 (mean 61 588.75, range 2292–10 959 892) sequences for 6-week samples and a total of 98 461 252 (mean 623 172.88, range 74 876–4 113 488) sequences for 1-year samples. Amplicon sequence variants from 6-week samples were taxonomically represented by four phyla and 29 genera, whereas samples taken at 1 year of age were represented by 16 phyla and 157 genera. Overall bacterial richness and evenness (α diversity) increased over time (from 6 weeks to 1 year) (see Supplementary material, Figure S1).

Relationship between intrapartum antibiotic use and infant microbial diversity and community composition

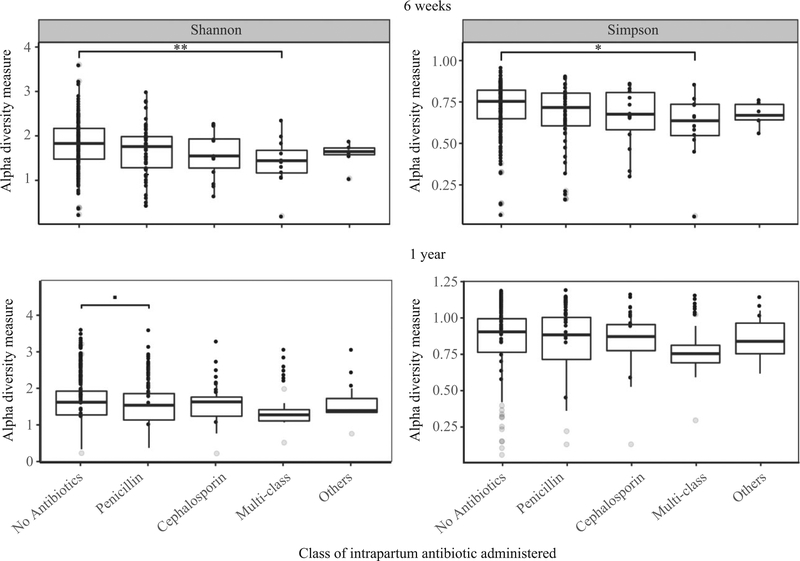

Alpha diversity indices were consistently lower for infants whose mothers received any type of intrapartum antibiotic compared with infants whose mothers did not at both time-points (see Supplementary material, Figure S2). At 6 weeks, this difference was statistically significant when comparing the multi-class group with the no-antibiotics group (Shannon t statistic = −2.374, adjusted P = 0.02; Simpson t statistic = −1.907, adjusted P = 0.06; Figure 1). At 1 year postpartum, microbial diversity (mean Shannon index) in the penicillin-only group was lower compared with the no-antibiotics group, although it did not reach significance (Shannon t statistic = −1.731; adjusted P = 0.09; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Infant gut microbial α diversity by specific class of maternal intrapartum antibiotic administered. Box plots of the α diversity scores (Shannon and Simpson). Significance values from linear models adjusted for infant birthweight, feeding mode, prenatal antibiotic use and infant postpartum antibiotic use: 6 weeks (n = 266), 1 year (n = 152). **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ■P < 0.1.

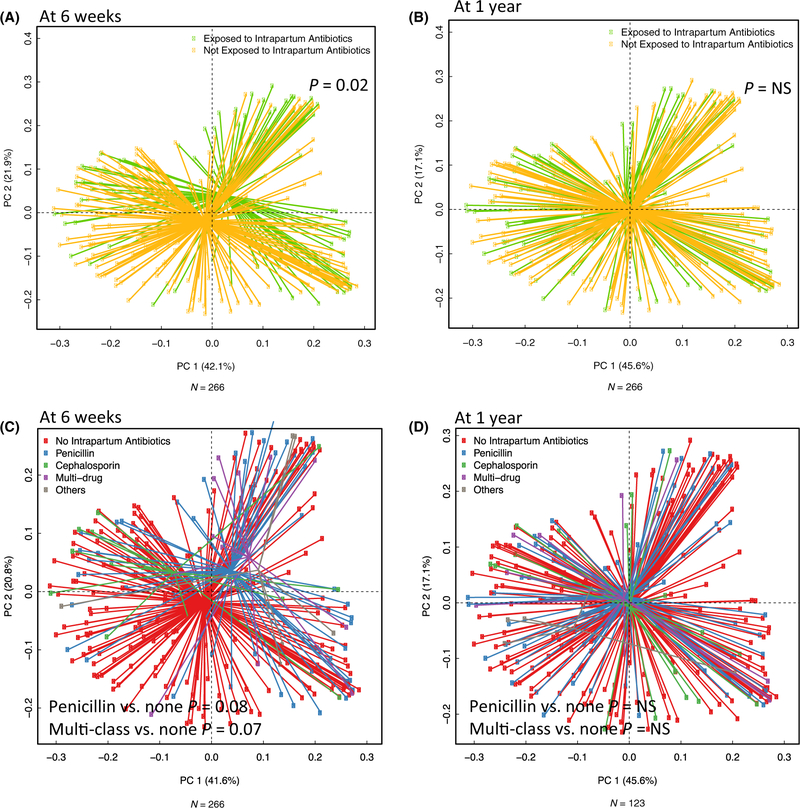

Bacterial community structure and composition of the infants’ intestinal microbiota at 6 weeks differed significantly based on intrapartum antibiotic use even after adjusting for antibiotic use during pregnancy and infancy, feeding mode, duration of breastfeeding and infant antibiotic use [permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) F statistic = 2.32; P < 0.05; Figure 2A). When examining the antibiotic classes administered with principle coordinates analysis plots, infants in the penicillin and multi-class groups clustered separately (but were not different at a 5% significance level) from those who were not exposed to any class of intrapartum antibiotic at 6 weeks (penicillin PERMANOVA F statistic = 1.8; P < 0.1; multi-class PERMANOVA F statistic = 1.7; P < 0.1; Figure 2B). The clustering with principle coordinates analysis, however, did not persist at 1 year of age (Figure 2C, D).

Figure 2.

(A–D) Bacterial community composition at 6 weeks and 1 year. Generalized UniFrac principle components analysis plots illustrating that although samples from the infant gut microbiome at 6 weeks and 1 year overlap based on specific class of intrapartum antibiotic administered, there was some visual separation at 6 weeks that was not evident at 1 year. The association between intrapartum antibiotic use and microbiome community profiles at (A) 6 weeks (and (B) 1 year. The association between specific classes of intrapartum antibiotic use and microbiome community profiles at (C) 6 weeks and (D) 1 year. Values of P were derived from multivariable PERMANOVA models (adjusted for antibiotic use during pregnancy and infancy, feeding mode, duration of breastfeeding and infant antibiotic use).

Taxa associated with intrapartum antibiotic use

To determine taxa that were differentially abundant, we used results from the MZILN model (adjusted for feeding mode, time of solid food introduction, and antibiotic use during pregnancy and infancy). Intrapartum antibiotic use was associated with the abundance of several taxa at 6 weeks and 1 year of age. Using data from both time-points, exposure to any class of intrapartum antibiotic was significantly associated with a reduction in proportional abundance of Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Blautia, Roseburia and Ruminococcus; and increased levels of Oscillospora, Pseudobacter and Veillonella dispar irrespective of age at sample collection (see Supplementary material, Table S1).

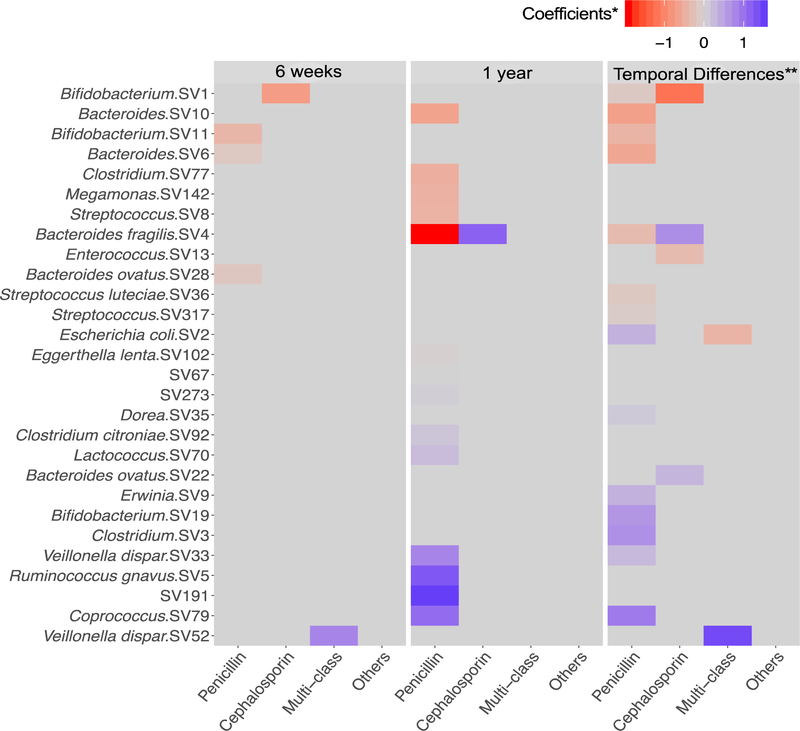

With respect to specific classes of antibiotics administered, the stool microbiota at 6 weeks revealed that the amplicon sequence variants annotated as Bacteroides, Bacteroides ovatus and Bifidobacterium, were significantly lower in abundance in infants in the penicillin group compared with unexposed infants. Bifidobacterium was also markedly lower in infants exposed to cephalosporins, compared with unexposed infants, whereas Veillonella dispar was significantly greater in abundance in the multi-class group compared with the unexposed group (Figure 3). At 1 year, several taxa including Bacteroides, Bacteroides fragilis, Clostridium, Meganomas and Streptococcus, were significantly lower, whereas Coprococcus and Ruminococcus gnavus were in significantly higher abundance in infants in the penicillin group compared with unex-posed infants (Figure 3). In contrast to the penicillin group, the use of cephalosporins was significantly associated with higher levels of Bacteroides fragilis.

Figure 3.

Taxa that are significantly associated with maternal antibiotic exposure (unexposed infants as the reference group). Heatmap highlights results from the MZILN model. Using the log-scale changes in absolute abundance, the MZILN coefficients identify taxa that were associated with specific classes of maternal antibiotic exposure for 6-week samples and 1-year samples. **Additionally, abundance data from both time-points were used to examine taxa that significantly differed in the change over time from 6 weeks to 1 year (temporal changes) comparing infants exposed to maternal intrapartum antibiotics with those who were not.

To reveal taxa that significantly differed over time when comparing antibiotic-exposed and unexposed infants, we used abundance data from both time-points and compared changes over time (temporal change from 6 weeks to 1 year). Many taxa such as Bacteroides fragilis, Bifidobacterium, Clostridium, Streptococcus and Coprococcus were observed to have significantly different changes in abundance over time when comparing the penicillin group with those unexposed to intrapartum antibiotics (Figure 3). Specifically, we observed a significantly lower increase in taxa from genera Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium; a greater proportional rise in Coprococcus and a greater reduction in abundance of Escherichia coli over time in infants exposed to penicillins. Bifidobacterium and Enterococcus had significantly lower increases over time in infants exposed to cephalosporins. The use of penicillins and cephalosporins was associated with a differential rise in Bacteroides fragilis over time but in different directions (penicillins were associated with a smaller rise whereas cephalosporins were associated with a greater rise). Similarly, the penicillin and multi-class groups were associated with the level of decline of Escherichia coli over time in differing directions (Figure 3).

Intrapartum antibiotic use and taxonomic composition and function of gut bacterial metagenome

Given the observed effects of intrapartum antibiotics on the infant gut microbiome, we sought to gain insight into differences in species-level composition and functional capabilities present in bacterial communities using metagenomics. Due to the limited sample size (paired samples from a subset of 32 infants were included in this analysis) we compared infants exposed to maternal intrapartum antibiotics with those who were not. Infants born to mothers who received antibiotics during labour and delivery had differentially abundant functional meta-genomes at 6 weeks and 1 year (see Supplementary material, Figure S3A–B). We found a lower representation of genes involved in γ-aminobutyric acid36 shunt (a detour to the tricarboxylic acid cycle) at 6 weeks; and in genes involved in an incomplete tricarboxylic acid cycle at 1 year.

Discussion

Main findings

We investigated the potential impact of maternal intrapartum antibiotic exposure on the developing microbiome of her offspring in 266 mother–infant dyads. Intrapartum antibiotics were associated with indicators of the maturation of the infant gut microbiome based on differences in bacterial diversity, community composition and diminution of taxa prominent in immune modulation, such as Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium, in the first year of life. We observed that the class of antibiotic administered during labour and delivery was related to microbial developmental trajectories of keystone taxa in the infants.

Our results represent one of the largest cohorts addressing the impact of protocols for antibiotic prophylaxis during labour and delivery in the USA. We have found that the infant microbiome differs over the course of the first year of life with respect to intrapartum antibiotics exposure in the context of GBS prophylaxis, preoperative procedures, intrapartum fever or chorioamnionitis. Despite their widespread use, there are few published data on the potential effects of antibiotics on the infant and maternal microbiome during the process of labour and delivery at term gestation.37–44 To our knowledge, no large cohort study has examined the effect of specific classes of antibiotics on the developing infant intestinal microbiota of full-term infants. This is relevant in practice because different classes of antibiotics are chosen for various indications, and awareness of the differing impacts on the infant might inform interventions for the infant such as antibiotic-recovery probiotics.

In our study, we observed that intrapartum antibiotic exposure was independently associated with the decreased abundance of several bacteria including Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium and Blautia in the first year of life. Our findings support other studies that suggested a particular microbiome signature, with low abundance of Bacteroides, with intrapartum antibiotic use.39–41,45 In our study, Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium also differed in abundance over time when comparing infants exposed to penicillin-like antibiotics with infants who were not exposed to any type of antibiotic during labour and delivery. This finding is similar to those of previous studies focused on the use of maternal antibiotics in general, particularly with the decrease in Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium.38–43,46,47 One study40 observed significant effects of GBS prophylaxis on the infant gut microbiome at 6 months among 150 pregnancies for members of Clostridiaceae, Ruminococcoceae and Enterococcaceae whereas another41 (n = 83) found lower levels of Bifidobacterium and Escherichia at 12 weeks of life in infants of mothers exposed to intrapartum antibiotics.

Our study also suggests that the class of antibiotic administered (and possibly the underlying indication) has significant and differing effects on the infant microbiome, and that penicillins have the most sustained impact in the first year of life. The impact of two or more classes of drugs (multi-class group) administered at labour and delivery on the early gut microbiome has not been described before in full-term infants. A previous study48 reported that multi-drug high-risk clones present in neonates in the intensive care unit (ICU) were absent at 2 years of age, suggesting that the gut of a preterm infant recovers fully when the infant is discharged from the ICU. However, Gasparrini et al.49 observed that the use of b-lactam antibiotics in the ICU in premature infants acutely perturbs the infant gut microbiota whereas other drugs, such as aminoglycosides (e.g. gentamicin), were less disruptive. Our findings do not suggest the need to reassess prophylaxis protocols, neither do they infer detrimental effects of intrapartum antibiotics on the infant. Rather, these results offer opportunities to understand how these interventions potentially impact the infant long-term, and highlight potential opportunities to intervene with dietary, pre- or probiotic regimens. Although our data suggest that the impact of multi-class antibiotics does not seem to persist beyond 6 weeks, it is important to consider that the resulting effect of perturbation at a critical window of immune programming in early infancy may have long-term implications for competent immune development.7–9,50–52

Many of the genera decreased in association with intrapartum antibiotic exposure have been implicated in critical immune training.53,54 Antibiotic exposure has been shown to cause altered immune function and atopic disease in murine models where loss of keystone taxa resulted in reduced regulatory T cells,55 reduced maturation of natural killer T cells,56,57 increased immunoglobulins (IgE), and prevention of postnatal T helper type 1 cell maturation.58,59 Distinct community composition patterns have been associated with atopic disease later in life, including reduced overall diversity and decreased Bacteroides in early infancy,60–62 which was an important ‘missing microbe’ in the antibiotics-exposed infants in our study. Associations between antibiotic exposure during infancy and risk of immune-mediated diseases have been reported,63–66 but there remains a paucity of data highlighting the potential mediating effects of antibiotics on longitudinal microbial acquisition.

Large observational studies, although unable to determine a causal relationship, have highlighted the association between prenatal antibiotic use,67–69 postnatal antibiotics63 and increased risk of asthma, allergy and atopy in childhood.64,65,70,71 A large cohort has identified risk of asthma in preschool-aged children with antibiotic use in any trimester of pregnancy, but more significantly in the third trimester, supporting the potential role of shifts in the maternal microbiome, vertical transmission and early-life intestinal microbiota in asthma development.72 Additionally, studies such as the Prevention of RSV: Impact on Morbidity and Asthma cohort found cumulative effects of the exposure to antibiotics on the risk of childhood asthma.73 These studies support the association between antimicrobials during pregnancy, delivery and infancy with immune-mediated disease, and the potential role of perturbations in microbial community composition in increased disease risk.3

Strengths and limitations

The smaller number of infants observed in the non-penicillin groups (the multi-class and other-class groups) might have impacted our ability to identify taxa associated with the multi-class or other groups. Data regarding the timing, dose and duration of intrapartum antibiotics were not collected in this study. However, it is unlikely that the protocol for antibiotic administration differed because this is a single-site study. Furthermore, being a single US cohort, our findings require further validation in more diverse populations. Despite these limitations, a major strength of this study was the use of the MZILN model, a model that allows for evaluation of compositional data and adjustment for key variables including birthweight, feeding mode, and prenatal and infant antibiotic use. The longitudinal analysis of multiple samples from the same subjects allows evaluation of the developmental trajectory of the microbiome in relationship to exposures in this critical window. The study of metagenomics also affords the opportunity to explore the metabolic pathways of microbial communities during this dynamic time of microbiome acquisition. However, additional studies are required to determine whether these observed differentially abundant metagenome functions are associated with specific taxonomic changes due to intrapartum antibiotic use.

Interpretation

Overall, our data suggest that the effect of intrapartum antibiotics on the infant intestinal microbiome might persist until at least age 1 year. Alterations in the early gut microbiota by intrapartum antibiotics might impact immune training and lifelong risk; however, additional prospective studies are required – particularly to evaluate the effect of specific types of antibiotics.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight that exposure to maternal intrapartum antibiotics is associated with lower diversity, altered community composition and differential abundance of specific microbes in infants as their microbiome develops over the first year of life. Our findings highlight the possibility that the altered development of the microbiome in early life and the subsequent impact on early immune training might be the mechanism behind the associations identified in large epidemiological studies linking early-life antibiotic exposure and increased risk of immune-mediated diseases such as asthma, allergy and atopy. Specific classes of antibiotics administered, and their indications, may have varying impacts on the infant gut colonisation pattern. Clarifying the impact of the different classes of antibiotics during labour and delivery on infant microbial colonisation patterns is essential for understanding the potential health implications and identifying strategies to intervene and preserve a healthy microbiome that promotes a balanced immune function.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Bacterial richness and evenness (α diversity) increased over time (from 6 weeks to 1 year). All differences were statistically different (P < 0.0001).

Figure S2. Boxplots of α diversity scores based on intrapartum antibiotic exposure at (A) 6 weeks (n = 266); and (B) 1 year (n = 152).

Figure S3. Differentially abundant functional metagenomes at 6 weeks and 1 year. Functional characterisation of the infant faecal microbiome differs at (A) 6 weeks and (B) 1 year (n = 32).

Appendix S1. Supplementary Methods.

Table S1. Marginalised zero-inflated logistic normal (MZILN) results for any intrapartum MZILN model estimates (P<0.05) for amplicon sequence variants that were significantly associated with intrapartum antibiotic use.

Acknowledgements

Our heartfelt appreciation goes to the participating families and staff members of the NHBCS. We specially thank the entire labour and delivery staff (including clinical and administrative teams) at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center for their continued support of the NHBCS.

Funding

US National Institutes Health (NIH) under award numbers 1P20ES018175–02, NIEHS P01ES022832, NIEHS P20ES018175, NIGMS P20GM104416 and NLM K01LM011985; and the US Environmental Protection Agency (RD83459901 and RD83544201). The awarded grant included external peer review for scientific quality. NIH’s role as the primary sponsor for this work was principally to ensure the study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice.

Footnotes

Disclosure of interests

None declared. Completed disclosure of interest forms are available to view online as supporting information.

Details of ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth (14 May 2013; STUDY00020844: New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study).

Additional information

The sequence data have been deposited and are available from the Sequence Read Archive with the repository accession number PRJNA296814.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

References

- 1.Langdon A, Crook N, Dantas G. The effects of antibiotics on the microbiome throughout development and alternative approaches for therapeutic modulation. Genome Med 2016;8:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vangay P, Ward T, Gerber JS, Knights D. Antibiotics, pediatric dysbiosis, and disease. Cell Host Microbe 2015;17:553–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Life at the beginning: perturbation of the microbiota by antibiotics in early life and its role in health and disease. Nat Immunol 2014;15:307–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinross JM, Darzi AW, Nicholson JK. Gut microbiome–host interactions in health and disease. Genome Med 2011;3:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sjogren YM, Tomicic S, Lundberg A, Bottcher MF, Bjorksten B, Sverremark-Ekstrom E, et al. Influence of early gut microbiota on the maturation of childhood mucosal and systemic immune responses. Clin Exp Allergy 2009;39:1842–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez de Tejada B Antibiotic use and misuse during pregnancy and delivery: benefits and risks. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:7993–8009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science (New York, NY) 2012;336:1268–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renz H, Brandtzaeg P, Hornef M. The impact of perinatal immune development on mucosal homeostasis and chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2011;12:9–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL, Shima T, Karaoz U, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell 2009;139:485–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker RW, Clemente JC, Peter I, Loos RJF. The prenatal gut microbiome: are we colonized with bacteria in utero? Pediatric Obesity 2017;12:3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stinson LF, Payne MS, Keelan JA. Planting the seed: origins, composition, and postnatal health significance of the fetal gastrointestinal microbiota. Crit Rev Microbiol 2017;43:352–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nuriel-Ohayon M, Neuman H, Koren O. Microbial changes during pregnancy, birth, and infancy. Front Microbiol 2016;7:1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eggesbo M, Moen B, Peddada S, Baird D, Rugtveit J, Midtvedt T, et al. Development of gut microbiota in infants not exposed to medical interventions. APMIS 2011;119:17–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mshvildadze M, Neu J, Shuster J, Theriaque D, Li N, Mai V. Intestinal microbial ecology in premature infants assessed with non-culture-based techniques. J Pediatr 2010;156:20–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turroni F, Ribbera A, Foroni E, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. Human gut microbiota and bifidobacteria: from composition to functionality. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2008;94:35–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer C, Bik EM, DiGiulio DB, Relman DA, Brown PO. Development of the human infant intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol 2007;5:e177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skurnik D, Ruimy R, Ready D, Ruppe E, Bernede-Bauduin C, Djossou F, et al. Is exposure to mercury a driving force for the carriage of antibiotic resistance genes? J Med Microbiol 2010;59:804–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adlerberth I, Wold AE. Establishment of the gut microbiota in Western infants. Acta Paediatr 2009;98:229–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adlerberth I Factors influencing the establishment of the intestinal microbiota in infancy. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program 2008;62:13–29; discussion 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penders J, Thijs C, Vink C, Stelma FF, Snijders B, Kummeling I, et al. Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics 2006;118:511–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker WA. Bacterial colonization of the newborn gut, immune development, and prevention of disease. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser 2017;88:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujimura KE, Lynch SV. Microbiota in allergy and asthma and the emerging relationship with the gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 2015;17:592–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka M, Nakayama J. Development of the gut microbiota in infancy and its impact on health in later life. Allergol Int 2017;66:515–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butel MJ, Waligora-Dupriet AJ, Wydau-Dematteis S. The developing gut microbiota and its consequences for health. J Dev Orig Health Dis 2018;9:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farzan SF, Karagas MR, Chen Y. In utero and early life arsenic exposure in relation to long-term health and disease. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2013;272:384–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert-Diamond D, Emond JA, Baker ER, Korrick SA, Karagas MR. Relation between in utero arsenic exposure and birth outcomes in a cohort of mothers and their newborns from New Hampshire. Environ Health Perspect 2016;124:1299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newton RJ, McLellan SL, Dila DK, Vineis JH, Morrison HG, Eren AM, et al. Sewage reflects the microbiomes of human populations. MBio 2015;6:e02574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huse SM, Young VB, Morrison HG, Antonopoulos DA, Kwon J, Dalal S, et al. Comparison of brush and biopsy sampling methods of the ileal pouch for assessment of mucosa-associated microbiota of human subjects. Microbiome 2014;2:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huse SM, Mark Welch DB, Voorhis A, Shipunova A, Morrison HG, Eren AM, et al. VAMPS: a website for visualization and analysis of microbial population structures. BMC Bioinform 2014;15:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJ, Holmes SP. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods 2016;13:581–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006;72:5069–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e61217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z, Lee K, Karagas MR, Madan JC, Hoen AG, O’Malley AJ, et al. Conditional regression based on a multivariate zero-inflated logistic normal model for microbiome relative abundance data. arXiv:170907798v2 [statAP]. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang CH. Nearly unbiased variable selection under minimax concave penalty. Ann Stat 2010;38:894–942. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parks DH, Tyson GW, Hugenholtz P, Beiko RG. STAMP: statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics 2014;30:3123–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atlas C, Aad G, Abajyan T, Abbott B, Abdallah J, Abdel Khalek S, et al. Jet energy measurement and its systematic uncertainty in proton–proton collisions at s = 7 TeV with the ATLAS detector. Eur Phys J C Part Fields 2015;75:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Power ML, Quaglieri C, Schulkin J. Reproductive microbiomes. Reprod Sci (Thousand Oaks, Calif) 2017;24:1482–1492. 1933719117698577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roesch LF, Silveira RC, Corso AL, Dobbler PT, Mai V, Rojas BS, et al. Diversity and composition of vaginal microbiota of pregnant women at risk for transmitting Group B Streptococcus treated with intrapartum penicillin. PLoS ONE 2017;12:e0169916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stearns JC, Simioni J, Gunn E, McDonald H, Holloway AC, Thabane L, et al. Intrapartum antibiotics for GBS prophylaxis alter colonization patterns in the early infant gut microbiome of low risk infants. Sci Rep 2017;7:16527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Sitarik A, Levin AM, Lynch SV, Havstad S, Ownby DR, et al. Maternal group B Streptococcus and the infant gut microbiota. J Dev Orig Health Dis 2016;7:45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Azad MB, Konya T, Persaud RR, Guttman DS, Chari RS, Field CJ, et al. Impact of maternal intrapartum antibiotics, method of birth and breastfeeding on gut microbiota during the first year of life: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 2016;123:983–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corvaglia L, Tonti G, Martini S, Aceti A, Mazzola G, Aloisio I, et al. Influence of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis for group B streptococcus on gut microbiota in the first month of life. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;62:304–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Persaud RR, Azad MB, Chari RS, Sears MR, Becker AB, Kozyrskyj AL, et al. Perinatal antibiotic exposure of neonates in Canada and associated risk factors: a population-based study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2015;28:1190–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aloisio I, Mazzola G, Corvaglia LT, Tonti G, Faldella G, Biavati B, et al. Influence of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis against group B Streptococcus on the early newborn gut composition and evaluation of the anti-Streptococcus activity of Bifidobacterium strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2014;98:6051–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mueller NT, Whyatt R, Hoepner L, Oberfield S, Dominguez-Bello MG, Widen EM, et al. Prenatal exposure to antibiotics, cesarean section and risk of childhood obesity. Int J Obes 2015;39:665–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van de Wijgert JH, Jespers V. The global health impact of vaginal dysbiosis. Res Microbiol 2017;168:859–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chernikova DA, Koestler DC, Hoen AG, Housman ML, Hibberd PL, Moore JH, et al. Fetal exposures and perinatal influences on the stool microbiota of premature infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29:99–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moles L, Gomez M, Jimenez E, Fernandez L, Bustos G, Chaves F, et al. Preterm infant gut colonization in the neonatal ICU and complete restoration 2 years later. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015;21:936 e1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gasparrini AJ, Crofts TS, Gibson MK, Tarr PI, Warner BB, Dantas G. Antibiotic perturbation of the preterm infant gut microbiome and resistome. Gut Microbes 2016;7:443–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Atarashi K, Honda K. Microbiota in autoimmunity and tolerance. Curr Opin Immunol 2011;23:761–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mazmanian SK, Round JL, Kasper DL. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature 2008;453:620–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yassour M, Vatanen T, Siljander H, Hamalainen AM, Harkonen T, Ryhanen SJ, et al. Natural history of the infant gut microbiome and impact of antibiotic treatment on bacterial strain diversity and stability. Sci Transl Med 2016;8:343ra81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell 2012;148:1258–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Donnet-Hughes A, Perez PF, Dore J, Leclerc M, Levenez F, Benyacoub J, et al. Potential role of the intestinal microbiota of the mother in neonatal immune education. Proc Nutr Soc 2010;69:407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Russell SL, Gold MJ, Hartmann M, Willing BP, Thorson L, Wlodarska M, et al. Early life antibiotic-driven changes in microbiota enhance susceptibility to allergic asthma. EMBO Rep 2012;13:440–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Noverr MC, Falkowski NR, McDonald RA, McKenzie AN, Huffnagle GB. Development of allergic airway disease in mice following antibiotic therapy and fungal microbiota increase: role of host genetics, antigen, and interleukin-13. Infect Immun 2005;73:30–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olszak T, An D, Zeissig S, Vera MP, Richter J, Franke A, et al. Microbial exposure during early life has persistent effects on natural killer T cell function. Science (New York, NY) 2012;336:489–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hill DA, Siracusa MC, Abt MC, Kim BS, Kobuley D, Kubo M, et al. Commensal bacteria-derived signals regulate basophil hematopoiesis and allergic inflammation. Nat Med 2012;18:538–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oyama N, Sudo N, Sogawa H, Kubo C. Antibiotic use during infancy promotes a shift in the TH1/TH2 balance toward TH2-dominant immunity in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;107:153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abrahamsson TR, Jakobsson HE, Andersson AF, Bjorksten B, Engstrand L, Jenmalm MC. Low diversity of the gut microbiota in infants with atopic eczema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;129:434–40 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bjorksten B, Sepp E, Julge K, Voor T, Mikelsaar M. Allergy development and the intestinal microflora during the first year of life. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108:516–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bisgaard H, Li N, Bonnelykke K, Chawes BL, Skov T, Paludan-Muller G, et al. Reduced diversity of the intestinal microbiota during infancy is associated with increased risk of allergic disease at school age. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:646–52 e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Metsala J, Lundqvist A, Virta LJ, Kaila M, Gissler M, Virtanen SM. Prenatal and post-natal exposure to antibiotics and risk of asthma in childhood. Clin Exp Allergy 2015;45:137–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnson CC, Ownby DR, Alford SH, Havstad SL, Williams LK, Zoratti EM, et al. Antibiotic exposure in early infancy and risk for childhood atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;115:1218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dom S, Droste JH, Sariachvili MA, Hagendorens MM, Oostveen E, Bridts CH, et al. Pre- and post-natal exposure to antibiotics and the development of eczema, recurrent wheezing and atopic sensitization in children up to the age of 4 years. Clin Exp Allergy 2010;40:1378–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johnson CC, Ownby DR. Allergies and asthma: do atopic disorders result from inadequate immune homeostasis arising from infant gut dysbiosis? Exp Rev Clin Immunol 2016;12:379–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lapin B, Piorkowski J, Ownby D, Freels S, Chavez N, Hernandez E, et al. Relationship between prenatal antibiotic use and asthma in at-risk children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015;114:203–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Timm S, Schlunssen V, Olsen J, Ramlau-Hansen CH. Prenatal antibiotics and atopic dermatitis among 18-month-old children in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Clin Exp Allergy 2017;47:929–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wegienka G, Havstad S, Zoratti EM, Kim H, Ownby DR, Johnson CC. Combined effects of prenatal medication use and delivery type are associated with eczema at age 2 years. Clin Exp Allergy 2015;45:660–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ong MS, Umetsu DT, Mandl KD. Consequences of antibiotics and infections in infancy: bugs, drugs, and wheezing. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014;112:441–5.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Droste JH, Wieringa MH, Weyler JJ, Nelen VJ, Vermeire PA, Van Bever HP. Does the use of antibiotics in early childhood increase the risk of asthma and allergic disease? Clin Exp Allergy 2000;30:1547–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mulder B, Pouwels KB, Schuiling-Veninga CC, Bos HJ, de Vries TW, Jick SS, et al. Antibiotic use during pregnancy and asthma in preschool children: the influence of confounding. Clin Exp Allergy 2016;46:1214–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu P, Feldman AS, Rosas-Salazar C, James K, Escobar G, Gebretsadik T, et al. Relative importance and additive effects of maternal and infant risk factors on childhood asthma. PLoS ONE 2016;11:e0151705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Bacterial richness and evenness (α diversity) increased over time (from 6 weeks to 1 year). All differences were statistically different (P < 0.0001).

Figure S2. Boxplots of α diversity scores based on intrapartum antibiotic exposure at (A) 6 weeks (n = 266); and (B) 1 year (n = 152).

Figure S3. Differentially abundant functional metagenomes at 6 weeks and 1 year. Functional characterisation of the infant faecal microbiome differs at (A) 6 weeks and (B) 1 year (n = 32).

Appendix S1. Supplementary Methods.

Table S1. Marginalised zero-inflated logistic normal (MZILN) results for any intrapartum MZILN model estimates (P<0.05) for amplicon sequence variants that were significantly associated with intrapartum antibiotic use.