Abstract

Objective:

We describe the development of a lay-delivered behavioral intervention (“Do More, Feel Better”) for depressed senior center clients, and we present preliminary data from a pilot RCT on 1. the feasibility of training lay volunteers to fidelity; and 2. the acceptability, impact, and safety of the intervention.

Methods:

We trained 11 volunteers at two aging service settings in “Do More, Feel Better” and randomized 18 depressed clients to receive the Intervention or Referral to mental health services.

Results:

Pilot data indicated that we can successfully train and certify 64% of older volunteers, and that depressed clients receiving the intervention reported high levels of session attendance and satisfaction. While there were no significant differences in 12-week reduction in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores between groups, Intervention clients showed an 8-point reduction in comparison to 0-point reduction among Referral clients.

Conclusions:

“Do More, Feel Better” has the potential of transferring evidence-based behavioral interventions to the hands of supervised lay volunteers, and can address the insufficient workforce providing geriatric mental health services.

Clinical Trials Number:

Keywords: depression, behavioral activation, lay-health workers, task-sharing, geriatrics, aging service settings

Introduction

The 2012 IOM report “Mental Health and Substance Abuse Workforce for Older Adults” highlighted the dearth of mental health providers for older adults and the need to develop a workforce of nontraditional providers to serve this growing population.1 Some investigators have proposed that lay community health workers may be able to screen and provide brief psychosocial interventions for geriatric mental health and substance abuse disorders, given an expanding evidence base for the feasibility and effectiveness of such efforts2.

In light of this movement, we have simplified Behavioral Activation for delivery by lay volunteers in senior centers and labelled it “Do More, Feel Better”. Our work and others has demonstrated the need for such an intervention given the high prevalence of elevated depressive symptoms in aging service settings3 and lack of available and acceptable mental health services.4,5

In this paper we describe the background for and development of “Do More, Feel Better” for depressed senior center clients. We present data from a small pilot RCT on the intervention’s feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary impact.

Senior center clients

Older adults who attend senior centers across the country represent large numbers of mid to low-income seniors with multiple social service needs.6–8 The Older Americans Act (OAA) in 1965 spurred the growth of senior centers, with more recent amendments calling on increased accessibility and services for those with low income and limited resources.9 There are approximately 10,000 senior centers in the U.S., and each provides a variety of social, recreational, nutritional, case assistance, and health promotion programs and services. Many centers also support volunteer services, including volunteer-assisted health promotion efforts such as chronic disease self-management groups, exercise classes, stress management groups, and peer companionship programs.

Depression among senior center clients

Individuals who attend senior center have high rates of elevated depressive symptoms and are underserved. Ten percent of older adults experience clinically significant depression in New York City senior centers.3 In response to the growing mental health needs of older adults, some senior centers have begun to screen for depressive symptoms and offer mental health referrals. Even when treatment is available, however, elderly depressed individuals rarely accept a referral4 or engage in evidence-based treatment.5, 10–12 The unmet need we and others have documented is due to lack of available depression treatment within senior centers as well as poor client satisfaction with available community services. The public health significance of this problem is underscored given robust associations between untreated depression in older adults and poor health and mental health outcomes, and excessive and costly service use.13–16 Even milder forms of depression are associated with diminished quality of life among older adults.17

The need to develop a geriatric workforce of nontraditional providers:

At the national level, SAMSHA and the National Council on Aging have issued briefs highlighting the need to integrate mental health programs into aging service settings.9,18 These recommendations follow the lead set by primary care initiatives where mental health treatment is brought to the patient via Collaborative Care and other integrated models.19–20 As the geriatric mental health workforce is currently too small to meet the needs of community-dwelling older adults, the IOM report and others have identified nontraditional providers as a viable solution.1,2 Moreover, in a review supporting the effectiveness of para-professional therapists for a variety of mental health conditions, further research is called for given the limited number of professional therapists, cutbacks in third-party payments, and patient preferences for alternative treatments.21

Lay-delivered interventions may improve outcomes of depression, and may be both more cost effective and acceptable to seniors. However, integration of a new group of lay mental health providers into aging services requires that we build the evidence base that these providers are capable of offering quality services that yield effective outcomes. As part of these efforts, we must identify training and supervision needs in aging service settings, reliable methods to assure intervention fidelity, and protocols to evaluate and ensure client safety. Our long term agenda is to investigate strategies to grow the field capable of providing geriatric mental health services and to address the shortage of sustainable psychosocial interventions.

Lay-delivery of Behavioral Activation in senior centers:

Conceptual foundation:

In considering psychosocial interventions to adapt for delivery by lay volunteers for depressed senior center clients, we chose Behavioral Activation (BA) given its potential as a straightforward evidence-based intervention.22,23 Retaining key therapeutic strategies of BA, we simplified the intervention to match the skill set of lay volunteers. In this vein, we labelled our 12-session intervention “Do More, Feel Better” and described it as a wellness program.

BA is based on a model in which depression arises from a chronic reduction of positively reinforcing events.24,25 Depressed mood in turn leads to further avoidance and withdrawal from usual activities, creating a downward spiral in which fewer opportunities are available to experience positively reinforcing events. BA attempts to reverse this spiral by guiding individuals to reengage in potentially reinforcing pleasant and rewarding activities through a number of behavioral strategies (e.g., self-monitoring mood and activity level; activity scheduling).24,26–28 BA is well-suited to older adults; poor health and impairment in functioning often lead to diminished activity levels, a cycle further exacerbated by depression. BA encourages older adults to gradually increase activities that are feasible for them, and may increase self-efficacy through success experiences.29 Given its straightforward nature and structured format, BA may also be particularly helpful for individuals with low education or mild cognitive impairment.30

Empirical support:

BA, while a component of many cognitive-behavioral therapies, has been found effective as a stand-alone treatment for mid-life24,31–36 and elderly37–42 depressed patients in a variety of settings, with some evidence of benefits extending to 2 years.43–44 Several trials have investigated the use of Behavioral Activation (BA) by non-specialists, given the assertion that BA is a simple intervention that can be easily learned and disseminated.22,23 A randomized trial found that BA as delivered by mental health workers without psychotherapy experience was associated with greater improvement than primary care physicians’ usual care in depressive symptoms and social functioning.45 The community-based Healthy Ideas program, in which non-mental health case managers provided BA to individuals with mild depression, also demonstrated pre-post reductions in depression severity.46 International trials have found that lay health workers can successfully administer psychosocial interventions involving behavioral activation in primary care and other community-based settings.47 According to a systematic review, BA as a guided self-help treatment with minimal professional contact is effective for mild to moderate depression.48 In addition, an internet-based behavioral activation intervention with lay-health worker support has been shown to reduce symptoms of depression.49

Using a small randomized pilot design, our study aims were to examine: 1. the feasibility of training lay volunteers to fidelity in “Do More, Feel Better”; and 2. the acceptability, preliminary impact, and safety of the Intervention, in comparison to Referral to mental health services, by reporting client attendance at sessions, satisfaction, and 12-week reduction in depression severity (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HAM-D).50

Methods

Overview:

We piloted our lay volunteer training methods among 11 volunteers at two aging service settings in New York City: Lenox Hill Senior Center and Parkchester Naturally Occurring Retirement Community. We randomized 18 depressed clients to receive the “Do More, Feel Better” Intervention or Referral to mental health services, and we conducted follow up assessments at week 12. The study was approved by the Weill Cornell Medical College IRB. All volunteer and client participants provided written informed consent.

Study Participants:

Lay Volunteers: Senior center staff described the study and “Do More, Feel Better” intervention to volunteers whom they believed possessed good interpersonal skills. Eligibility criteria were: age≥60 years, and English-speaking. Clients: Eligibility criteria included: attended Lenox Hill or Parkchester; age≥60; English-speaking; PHQ-9≥10;51 MMSE≥24.52 Exclusion criteria included passive or active suicidal ideation; and diagnoses of bipolar depression, psychosis, or current alcohol or substance abuse as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM.53 We did not exclude clients currently receiving psychotherapy or antidepressant medication.

Randomization:

We randomized 18 depressed clients to receive the “Do More, Feel Better” Intervention or Referral to mental health services. Study investigators provided referrals to clients in both arms and encouraged them to follow through. RAs were aware of randomization status following baseline assessment but not of study aims.

Intervention:

We developed a “Do More, Feel Better” intervention manual, structured agendas for each meeting in the form of checklists, and supporting in-session materials. The agenda for initial meetings consists of: 1. Introduction of the “Do More, Feel Better” program and the role of a coach; 2. Review of PHQ-9 symptoms; 3. Psychoeducation about depression and the rationale for “Do More, Feel Better”, with corresponding client education forms; 4. Compilation of a list of pleasant and rewarding social, physical and recreational activities, each rated for their current difficulty level by the client (easy, medium, hard); and 5. Daily activity scheduling for the week. The agenda for the remaining 11 weekly sessions consists of: 1. Monitoring symptom severity via the PHQ-9; 2. Homework review and trouble-shooting; and 3. Ongoing daily activity scheduling for the week.

Assessment and management of clinical deterioration:

Coaches administer the PHQ-9 at the start of every meeting. Client endorsement of suicidal ideation on PHQ-9 item 9, or total scores that increase by >30% for 2 consecutive meetings trigger an assessment by study investigators and mental health referrals as indicated. Clients with active suicidal ideation are removed from the program and followed up by study investigators until they are connected to care. Coaches, however, do continue to meet with clients reporting passive suicidal ideation or increased depressive severity, and they provide ongoing support for clients’ pursuit of mental health care.

Volunteer training and supervision:

Volunteers undergo a rigorous training and certification process. Training consists of 4 2-hour sessions over 1 month and involves didactic and repeated role play experiences. Particular attention is given to issues of confidentiality, scope of role as a coach, interpersonal boundaries, handling client distress, and procedures for detection of clinical deterioration. Formal certification follows procedures we have developed for our psychotherapy studies and involve receiving “satisfactory” ratings of overall intervention fidelity by study investigators on simulated cases (scores ≥3 on the “Do More, Feel Better” Fidelity form). Ratings are made on a 6-point scale ranging from “very poor” to “very good”. Individual items reflect key elements of the intervention: symptom review, homework review, activity scheduling, agenda setting and time management, and communication and interpersonal skills, with a final global rating integrating all sets of skills. If volunteers do not achieve certification after a maximum of 5 simulated case attempts, they are dropped from ongoing participation. Following successful certification, volunteer coaches are approved to see depressed clients for the program, and they receive weekly supervision by study clinicians.

Measures:

Coach fidelity:

We assessed coach fidelity to “Do More, Feel Better” in two ways. First, volunteers documented via agenda checklists the number of session activities they completed per session; we report percentage complete across all sessions. Second, investigators assigned fidelity ratings based on in-person supervision of each session; we report percentage of sessions meeting “satisfactory” or higher fidelity (scores ≥3 on the “Do More, Feel Better” Fidelity form).

Client measures:

The PHQ-9 was administered routinely by senior center staff, and was used as a screen for further assessment by research assistants (RAs). In addition, RAs conducted PHQ-9 screening on-site to supplement recruitment efforts. Following consent of clients who screened positive, RAs assessed cognitive functioning with the MMSE and depressive symptoms using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM, with diagnoses assigned by the PI after review of symptoms. RAs assessed depressive symptom severity with the HAM-D at baseline and week 12. We report on number of “Do More, Feel Better” sessions attended out of 12 for each client, as well as use of psychotherapy and antidepressant medication. We assessed client satisfaction at week 12 using 3 items on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), and open-ended questions. We used ANCOVA to examine differences across groups in reduction in HAM-D scores, and report pre-post change scores within groups.

Results

Client participant flow and characteristics:

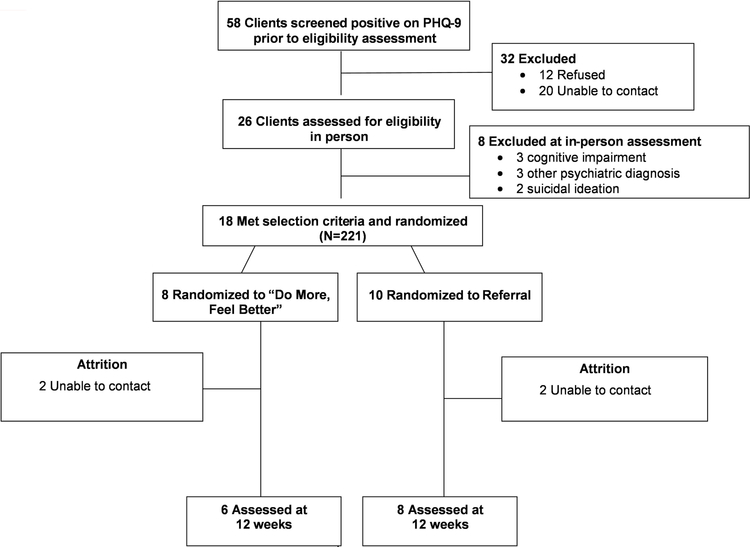

The study identified 58 clients scoring PHQ-9≥10 by center staff or RA (Figure 1). Twenty-six clients (45%) consented for baseline assessment, while 12 (21%) refused and 20 were unable to be contacted (34%). Of the 26 baselines, 18 met study eligibility criteria. Eight clients were excluded: 3 had a history of manic or psychotic episodes; 2 reported suicidal ideation; and 3 scored <24 on the MMSE. All eligible clients were willing to be randomized to receive the Intervention (n=8) versus Referral (n=10). Enrolled clients (n=18) had mean age of 76 (sd=8.3); 83% female; 11% non-Hispanic Black, 11% Hispanic; mean education 15 years (sd=2.6). 73% met SCID criteria for major depression, 14% for minor depression, and 13% endorsed subthreshold symptoms. At baseline, 3 Intervention and 3 Referral clients were receiving psychotherapy or antidepressant medication. 12-week data were available on 6 Intervention and 8 Referral clients, as four clients were unable to be contacted and lost to follow-up.

Figure 1.

Consort Chart for Pilot Trial of “Do More, Feel Better”

Feasibility: Lay volunteer certification and session fidelity:

Across the two centers, we trained 11 volunteers. Seven met rigorous certification standards, and 4 dropped out prior to training completion. Of the 7 certified coaches, 5 were female; 5 were Caucasian, 1 African-American, and 1 Native American; and 6 completed undergraduate education or higher. All coaches had a history of volunteerism and were naïve to delivery of mental health interventions. Certified coaches reported via agenda checklists that they completed 95% of session activities across all sessions. Investigator ratings based on in-person supervision indicated that 85% of sessions meet criteria for “satisfactory” fidelity (scores ≥3 on the “Do More, Feel Better” Fidelity form).

Acceptability:

Of 8 clients assigned to “Do More, Feel Better”, 7 attended 12 meetings and 1 attended 11. Mean total client satisfaction was 11 out of 12 (sd=1.7) at 12 weeks (available n=6), indicating high levels of satisfaction. Four clients indicated that “most or all of their needs were met” by the program and 2 that “some needs were met”; 6 were “mostly or very satisfied” with the program, and 5 that they “would come back to the coach if they were to seek help again”. Select client quotes at 12 weeks were: “My coach was great at encouraging me to do pleasurable activities”; “My coach told me about new ways I didn’t know about to feel better”; “She gave me new information and techniques to cope with depression.”

Preliminary impact:

We report on 6 “Do More, Feel Better” and 8 Referral subjects with 12-week follow up. An ANCOVA failed to reveal significant differences in 12-week HAM-D scores between groups (F(1,11)=2.475; p=0.144). Depressed clients randomized to “Do More, Feel Better” showed an 8 point reduction in HAM-D scores at 12 week follow-up (baseline mean=21.2 (sd=3.7) versus 12 week mean=13.2 (sd=4.3). Referral subjects in contrast showed no change in HAM-D scores (baseline mean=18.6 (sd=4.0) versus 12 week mean=18.6 (sd=7.5). Three Intervention and 4 Referral subjects received psychotherapy or antidepressant medication over the 12-week period.

Safety:

No client reported suicidal ideation on either coach-administered weekly PHQ-9s or RA-assessed HAM-D. None showed other evidence of clinical deterioration, as defined as total PHQ-9 scores that increased by >30% for 2 consecutive program meetings.

Case example:

The following case example represents a composite of our experiences providing “Do More, Feel Better” to depressed senior center clients.

Mrs. A is a 75 year-old African American woman who occasionally attends a nearby senior center for lunch. After lunch one day, a research assistant asked Mrs. A if she would be willing to sit down with her for a few minutes to fill out a brief “wellness” questionnaire. Mrs. A endorsed depressed mood, lack of interest, fatigue, and sleep difficulty on the PHQ-9. Her total score was 12, and so the research assistant sought informed consent for the study. Mrs. A was randomized to the “Do More, Feel Better” program, and she agreed to meet with a volunteer coach at the senior center.

At the first meeting, the volunteer coach introduced her role and further described the “Do More, Feel Better” program. The coach reviewed the client’s PHQ-9 and inquired about which symptoms were most distressing to Mrs. A and how they interfered with her life. Mrs. A discussed her difficulties coping with several chronic medical problems and following all or her doctors’ treatment recommendations. She also reported that she wasn’t getting things done around the house lately, and that she felt less connected and needed since her daughter moved away. The coach explained to Mrs. A that the goals of “Do More, Feel Better” were to re-establish routines that were important to her, and increase the quality of her life by engaging in more activities that were rewarding and meaningful to her. The coach discussed what depression looks like in older adults and how the “Do More, Feel Better” program could help. Mrs. A and her coach filled out a list of potentially pleasant and rewarding activities for her, and rated each for their difficulty level (see Figure 2). The coach ensured that they discussed a variety of activity domains, including self-care, physical, social, and recreational activities. Mrs. A then filled out a form with her coach to schedule several activities for the week that she felt she could accomplish and that might be “mood boosters” (see Figure 3).

Figure 2.

List of Pleasant and Rewarding Activities

Figure 3.

Weekly Activity Scheduling

Mrs. A and her coach met on a weekly basis to review the severity of her depression symptoms, review successes and challenges of her activity plans, and create new weekly activity plans. As meetings progressed, Mrs. A was able to continue to engage in activities that she found enjoyable and she felt more energy to do so. For example, she expanded the activities she attended at the senior center beyond lunch, including regular yoga classes and a political discussion group. At the conclusion of the 12-week program, Mrs. A’s PHQ-9 score went down to a 3. She reported feeling better about managing her household, attending to her health, and staying connected with her family and friends.

Discussion

Our pilot data provide preliminary evidence for the feasibility of “Do More, Feel Better.” First, we successfully trained and certified 64% of older volunteers as coaches. Volunteers who failed to certify dropped out of training prior to its completion in one month, either due to competing time priorities, lack of interest, or lack of perceived proficiency in the intervention. While some drop out or failure to certify is to be expected, we note the desirability of obtaining higher certification rates before disseminating our program on a wider basis. To this end we suggest use of more structured and focused interviews with volunteers to determine their eligibility for training, in line with those used by some mental health peer specialist programs.54,55 Second, we documented that 85% of the sessions of certified coaches meet “satisfactory” fidelity criteria as determined by in-session supervision. We hope to raise this rate in the future by incorporating audiotape review of sessions and more targeted feedback to coaches.

Our pilot data also showed acceptability of the intervention to depressed client participants, who demonstrated high attendance and satisfaction levels. While we did not observe significant differences in depression reduction between groups, clients who received “Do More, Feel Better” showed a promising signal in reduction in depression severity.

Study limitations include a small sample size of volunteers, clients, and senior centers. Secondly, the comparison group, referral to mental health services, was not an active intervention. Thirdly, while acceptable, the 85% intervention fidelity rate we achieved could be improved by refining our training and supervision methods. In light of these limitations, our work has demonstrated the potential of transferring such an evidence-based intervention to the hands of supervised lay providers, and calls for more rigorous examination of its feasibility, acceptability, safety, and clinical impact.

Conclusion

“Do More, Feel Better” is a lay volunteer-delivered Behavioral Activation intervention with potential to address a growing problem in health care today, as documented by the 2012 IOM report on the mental health workforce for older adults. Through increased screening in aging service settings, depression detection has increased but without the capacity to meet the steady increase of individuals in need or to provide the services that depressed clients are willing to accept. Training lay volunteers to work with older depressed adults using the “Do More, Feel Better” program provides an innovative alternative model that can help moderate this increased need. Advantages of the “Do More, Feel Better” program are that it: consists of evidence-based behavioral techniques geared to the skill set of older volunteers; makes use of existing volunteer resources that can address the insufficient workforce providing geriatric mental health services; and has potential for being an acceptable and sustainable real-world program.

Key points:

There is a need to investigate lay-delivered psychosocial interventions for geriatric mental health disorders, given lack of available professional mental health services.

Our pilot data support the feasibility and acceptability of lay-delivered Behavioral Activation for depressed senior center clients.

Lay-delivered Behavioral Activation has high potential for sustainability given existing volunteer resources in senior centers.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: National Institute of Mental Health R34 MH111849; P30 MH085943

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no interests to disclose.

Data Availability

The data generated during and/or analyzed in this study are available from praue@uw.edu on reasonable request or may be accessed via Synapse, and open access data repository, https://www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn18691337/files/56

References

- 1.Eden J, Maslow K, Le M, Blazer D. The Mental Health and Substance Use Workforce for Older Adults: In Whose Hands? : National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartels SJ, Aschbrenner KA, Rolin SA, Hendrick DC, Naslund JA, Faber MJ. Activating older adults with serious mental illness for collaborative primary care visits. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2013;36(4):278–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman J, Furst L. Addressing the needs of depressed older New Yorkers: A public-private partnership: EASE-D and other interventions. Internal Report: NYC Department for the Aging 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sirey JA. Engaging to improve engagement. Psychiat Serv 2013;64(3):205–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gum AM, Hirsch A, Dautovich ND, Ferrante S, Schonfeld L. Six-Month Utilization of Psychotherapy by Older Adults with Depressive Symptoms. Community mental health journal 2014;50(7):759–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calsyn RJ, Winter JR. Predicting older adults’ knowledge of services. Journal of social service research 1999;25(4):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pardasani MP. Senior centers: Increasing minority participation through diversification. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 2004;43(2–3):41–56. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner KW. Senior citizens centers: What they offer, who participates, and what they gain. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 2004;43(1):37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 9.NCOA. Annual Report: Improving the Lives of Older Americans. National Council on Aging 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pepin R, Leggett A, Sonnega A, Assari S. Depressive symptoms in recipients of home- and community-based services in the United States: Are older adults receiving the care they need? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2017; 25(12):1351–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olfson M, Blanco C, Marcus SC. Treatment of adult depression in the United States. JAMA Intern Med, 2016. 176(10): p. 1482–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byers AL, Arean PA, Yaffe K. Low use of mental health services among older Americans with mood and anxiety disorders. Psychiatric Services 2012;63(1):66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 2012 380: 2197–2223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eggermont LH, Penninx BW, Jones RN, et al. Depressive symptoms, chronic pain, and falls in older community-dwelling adults: the MOBILIZE Boston study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2012. 60:230–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byers AL, Sheeran T, Mlodzianowski AE, et al. Depression and risk for adverse falls in older home health care patients. Res Gerontol Nurs, 2008. 1:245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Hirsch JK, et al. Health status and suicide in the second half of life. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2010. 25:371–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia H and Lubetkin EI, Incremental decreases in quality-adjusted life years (QALY) associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms for U.S. Adults aged 65 years and older. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2017. 15(1): p. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SAMHSA. Behavioral Health, United States, 2012 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013; Rockville, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbody SM, IMPACT collaborative care programme reduces suicide ideation in depressed older adults. Evid Based Ment Health, 2007. 10:51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF, Bruce ML et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT study. Am J Psychiatry, 2009. 166:882–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christensen A, Jacobson NS. Who (or what) can do psychotherapy: the status and challenge of nonprofessional therapies. Psychological Science 1994;5(1):8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanter JW, Busch AM, Rusch LC. Behavioral activation: Distinctive features Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazzucchelli T, Kane R, Rees C. Behavioral activation treatments for depression in adults: a meta‐analysis and review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2009;16(4):383–411. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dimidjian S, Barrera M Jr., Martell C, Munoz RF, Lewinsohn PM. The origins and current status of behavioral activation treatments for depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2011;7:1–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewinsohn PM. A behavioral approach to depression. In: Katz RJFMM, ed. The psychology of depression: Contemporary theory and research Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1974:xvii, 318. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hopko DR, Lejuez C, Ruggiero KJ, Eifert GH. Contemporary behavioral activation treatments for depression: Procedures, principles, and progress. Clinical Psychology Review 2003;23(5):699–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lejuez C, Hopko D, Hopko S. The brief behavioral activation treatment for depression (BATD): A comprehensive patient guide. The brief Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression (BATD): A comprehensive patient guide 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martell CR, Addis ME, Jacobson NS. Depression in context: Strategies for guided action WW Norton & Co; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blazer DG. Self-efficacy and depression in late life: A primary prevention proposal. Aging & mental health 2002;6(4):315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter JF, Spates CR, Smitham S. Behavioral Activation group therapy in public mental health settings: a pilot investigation. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 2004;35(3):297. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coffman SJ, Martell CR, Dimidjian S, Gallop R, Hollon SD. Extreme nonresponse in cognitive therapy: can behavioral activation succeed where cognitive therapy fails? J Consult Clin Psychol 2007;75(4):531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Behavioral activation treatments of depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 2007;27(3):318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74(4):658–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ekers D, Richards D, Gilbody S. A meta-analysis of randomized trials of behavioural treatment of depression. Psychological Medicine 2008;38(05):611–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Truax PA, et al. A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 1996;64(2):295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazzucchelli T, Kane R, Rees C. Behavioral activation treatments for depression in adults: a meta‐analysis and review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2009;16(4):383–411. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cernin PA, Lichtenberg PA. Behavioral treatment for depressed mood: a pleasant events intervention for seniors residing in assisted living. Clinical Gerontologist 2009/05/27 2009;32(3):324–331. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chartier IS, Provencher MD. Behavioural activation for depression: Efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Journal of affective disorders 2013;145(3):292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gallagher DE, Thompson LW. Treatment of major depressive disorder in older adult outpatients with brief psychotherapies. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice 1982;19(4):482. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meeks S, Looney SW, Van Haitsma K, Teri L. BE-ACTIV: a staff-assisted behavioral intervention for depression in nursing homes. The Gerontologist 2008;48(1):105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snarski M, Scogin F, DiNapoli E, Presnell A, McAlpine J, Marcinak J. The effects of behavioral activation therapy with inpatient geriatric psychiatry patients. Behavior therapy 2011;42(1):100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson LW, Gallagher D, Breckenridge JS. Comparative effectiveness of psychotherapies for depressed elders. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 1987;55(3):385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallagher-Thompson D, Hanley-Peterson P, Thompson LW. Maintenance of gains versus relapse following brief psychotherapy for depression. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 1990;58(3):371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gortner ET, Gollan JK, Dobson KS, Jacobson NS. Cognitive–behavioral treatment for depression: Relapse prevention. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 1998;66(2):377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ekers D, Richards D, McMillan D, Bland JM, Gilbody S. Behavioural activation delivered by the non-specialist: phase II randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry January 1, 2011 2011;198(1):66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quijano LM, Stanley MA, Petersen NJ, et al. Healthy IDEAS: a depression intervention delivered by community-based case managers serving older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology 2007;26(2):139–156. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnett ML, Gonzalez A, Miranda J, Chavira DA, Lau AS. Mobilizing community health workers to address mental health disparities for underserved populations: A systematic review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research July 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chartier IS, Provencher MD. Behavioural activation for depression: Efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Journal of affective disorders 2013; 145(3):292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arjadi R, Nauta MH, Scholte WF, et al. Internet-based behavioural activation with lay counsellor support versus online minimal psychoeducation without support for treatment of depression: A randomised controlled trial in Indonesia. The Lancet Psychiatry 2018;5(9):707–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamilton M A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2001;16(9):606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III—R (SCID): I History, rationale, and description. Archives of General Psychiatry 1992;49(8):624–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Compton MT, Hankerson-Dyson D, Broussard B, et al. Public-academic partnerships: Opening Doors to Recovery: a novel community navigation service for people with serious mental illnesses. Psychiat Serv 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reed TA, Broussard B, Moore A, Smith KJ, Compton MT. Community navigation to reduce institutional recidivism and promote recovery: initial evaluation of opening doors to recovery in southeast Georgia. Psychiatric Quarterly 2014;85(1):25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raue PJ; 2019; Lay-delivered Behavioral Activation for depressed senior center clients: pilot RCT; Synapse [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]