Abstract

Introduction

Five U.S. states have proposed policies to require health warnings on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), but warnings’ effects on actual purchase behavior remain uncertain. This study evaluated the impact of SSB health warnings on SSB purchases.

Study design

Participants completed one study visit to a life-sized replica of a convenience store in North Carolina, U.S. Participants chose six items (two beverages, two foods, and two household products). One item was randomly selected for them to purchase and take home. Participants also completed a questionnaire. Researchers collected data in 2018 and conducted analyses in 2019.

Setting/participants

Participants were a demographically diverse convenience sample of 400 adult SSB consumers (usual consumption ≥12 ounces/week).

Intervention

Research staff randomly assigned participants to a health warning arm (SSBs in the store displayed a front-of-package health warning) or a control arm (SSBs displayed a control label).

Main outcome measures

The primary trial outcome was SSB calories purchased. Secondary outcomes included reactions to trial labels (e.g., negative emotions) and SSB perceptions and attitudes (e.g., healthfulness).

Results

All 400 participants completed the trial and were included in analyses. Health warning arm participants were less likely to be Hispanic and to be overweight/obese than control arm participants. In intent-to-treat analyses adjusting for Hispanic ethnicity and overweight/obesity, health warnings led to lower SSB purchases (adjusted difference, –31.4 calories; 95% CI= –57.9, –5.0). Unadjusted analyses yielded similar results (difference, –32.9 calories; 95% CI= –58.9, – 7.0). Compared with the control label, SSB health warnings also led to higher intentions to limit SSB consumption and elicited more attention, negative emotions, thinking about the harms of SSB consumption, and anticipated social interactions. Trial arms did not differ on perceptions of SSBs’ added sugar content, healthfulness, appeal/coolness, or disease risk.

Conclusions

Brief exposure to health warnings reduced SSB purchases in this naturalistic RCT. SSB health warning policies could discourage SSB consumption.

Trial registration

This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov .

INTRODUCTION

Excess consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) such as sodas, fruit drinks, and sports drinks is a pressing public health issue in the U.S. Average SSB consumption among U.S. adults remains well above recommended levels,1–3 increasing risk for several of the most common preventable chronic diseases in the U.S., including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.4–7 Nutrition education and other behavioral interventions can yield small reductions in SSB consumption among those they reach.8 However, the consensus among experts is that policy action is needed to achieve meaningful population-wide improvements in dietary behaviors and diet-related diseases.9–12 Requiring health warnings on SSB containers is one promising policy for addressing overconsumption of SSBs.

Five U.S. states have proposed policies that would require health warnings on the front of SSB containers.13–18 Experimental research on SSB warnings can inform future policies in the U.S. and globally. Several online studies have assessed SSB health warnings’ impact on hypothetical intentions to purchase SSBs.19–21 However, intentions are an imperfect predictor of behavior,22 and few studies have assessed behavioral outcomes. One quasi-experiment conducted in a hospital cafeteria found that graphic SSB health warnings (but not text SSB health warnings) were associated with lower SSB purchases,23 but this study did not use a randomized design. Another study used a randomized design and measured beverage purchases, but displayed beverages and health warnings on a computer screen, not in a retail environment.24 To understand the impact of SSB health warnings on purchase behaviors, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in naturalistic retail settings are needed. Such trials provide strong causal inference while also mimicking many real-world conditions consumers would experience if SSB health warning policies were implemented.

To inform obesity prevention policy, this study conducted an RCT in an immersive, naturalistic convenience store laboratory to estimate the impact of SSB health warnings on SSB purchases. This study also assessed the impact of SSB health warnings on behavioral intentions, cognitive and affective message reactions, and SSB perceptions and attitudes.

METHODS

Study Population

Participants were adults aged ≥18 years; could read, write, and speak English; and were current SSB consumers, defined as consuming at least one serving (12 ounces) per week of SSBs as assessed using an adapted version of the BEVQ-15 beverage frequency questionnaire.25 Research staff recruited and enrolled participants from May to September 2018 using Craigslist, Facebook, e-mail lists, university participant pools, in-person recruitment, and flyers. The University of North Carolina IRB approved all study procedures and all participants provided their written informed consent.

Intervention

The trial took place in a naturalistic convenience store laboratory located in the Fuqua Behavioral Lab at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, U.S. The trial store is a life-sized replica of a typical convenience store, selling foods, beverages, and household products at real-world prices. Naturalistic laboratory stores like the one used in this study provide an immersive experience that simulates a real shopping trip.26,27

Beverages for sale included popular SSBs in seven beverage categories: sodas, fruit drinks, sports drinks, energy drinks, sweetened ready-to-drink (RTD) teas, sweetened RTD coffees, and calorically flavored waters (Appendix Table 1). Research staff examined household purchase data from North Carolina28 to identify up to five popular products by volume purchased in each of the seven beverage categories. For all categories except sodas and fruit drinks, the store sold one product; the store sold five types of soda and two types of fruit drinks because these beverage categories comprise the majority of SSB calories consumed by U.S. adults.1,29 SSB containers were 8.0–16.9 ounces, reflecting the typical amount consumed in a single sitting.30

For each SSB sold, the store also sold a non-SSB that closely matched the selected SSB in brand, flavor, and container size (Appendix Table 1). Each soda, sports drink, energy drink, sweetened RTD tea, and flavored water was matched to the diet/low-calorie version of the product. Sweetened RTD coffee was matched to an unsweetened version of the same coffee, and fruit drinks were matched to similar 100% fruit juices. To more fully reflect the retail environment, the store also sold unflavored bottled water and non-calorically flavored sparkling water, despite these beverages having no corresponding SSBs.

The store also sold a variety of foods (e.g., chips, cookies, crackers, packaged fruit cups, nuts, cereal, canned soup, pasta) in both single-serving and multipack/family sizes as well as household products (e.g., shampoo, soap, toothpaste, napkins, garbage bags, over-the-counter medications, notebooks). These products were selected prior to the present study by the Behavioral Lab to interest participants and mimic a typical convenience store.

Beverages were priced to match standard retail prices in stores in lower- and middle-income areas surrounding the laboratory, similar to the approach used by others.24 To ensure participants selected beverages based on their preferences, rather than simply selecting the least expensive items, prices were held constant across conditions, and each SSB and its corresponding non-SSB were priced identically (Appendix Table 1). Prices for foods and household products remained at the levels that the Behavioral Lab had set previously to reflect real-world prices.

Research staff screened individuals for eligibility using an online questionnaire, inviting those eligible to schedule a time to visit Behavioral Lab to complete the study. At the study visit, participants enrolled and provided written informed consent. Recruitment materials and consent documents indicated that the study intended to examine factors affecting consumer behavior but did not reveal the study’s focus on SSBs or health warnings.

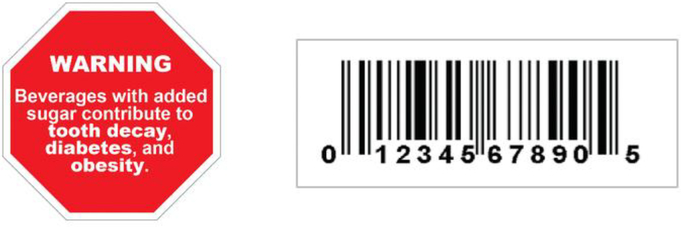

When participants arrived for their study visit, research staff assigned them to one of two trial arms: health warning or control. Study staff consulted a randomly ordered, pre-populated list of allocations and assigned participants to the next allocation on the list. The list was generated prior to study start by an independent biostatistician using simple randomization in a 1:1 allocation ratio. In the health warning arm, research staff applied a health warning label (Figure 1) directly to the front of all SSB containers in the trial store. The label displayed the message “WARNING: Beverages with added sugar contribute to tooth decay, diabetes, and obesity” in white text on a red octagon (1.5”-wide span) with a thin white border. This design was chosen for the SSB health warning because it performed well in an online randomized experiment.31 For the control arm, staff applied a 1” X 2.625” barcode label (Figure 1) to the front of all SSB containers. A barcode image was chosen for the control label because beverage containers already display barcodes. Using a control label, rather than a no-label control arm, ensured that the study controlled for the effect of putting a label on SSB containers.

Figure 1.

Sugar-sweetened beverage health warning label (left) and control label (right) used in the trial (actual sizes).

When participants entered the store, they received a shopping basket and $10 in cash. Research staff asked participants to shop as they usually would and to choose six items: two household products, two foods, and two beverages. Researchers asked participants to place their choices in their basket and instructed them that one of these six items would be randomly selected for them to purchase and take home using the $10 cash incentive provided at the start of the shopping task. This procedure ensured that selections were “real stakes” (i.e., that all six items participants chose were items they actually wished to purchase).

Research staff left the store while participants completed the shopping task. When participants were ready to check out, research staff recorded all of the products in their basket. Then, the researcher numbered the products and drew a number out of a basket to randomly select one item for the participant to purchase with the incentive cash at the product’s listed price. The researcher gave the participant the change owed in cash. Participants then completed a questionnaire on a computer in a private room. Afterward, they received the item they had purchased in the shopping task and were debriefed about the purpose of the study.

Measures

The primary trial outcome was SSB calories purchased, calculated as the sum of calories per container from all SSBs in the participants’ shopping basket when they completed the shopping task. Secondary purchase outcomes included purchase of any SSB, the number of SSBs purchased, and total calories purchased (from all products, including SSBs, non-SSBs, and foods).

Previous research on SSB19–21 and cigarette health warnings32–34 informed selection of secondary psychological outcomes. These outcomes were assessed in the post-shopping questionnaire with items and scales that have been validated or used in previous studies (Appendix Exhibit 1). Psychological secondary outcomes included intentions to limit consumption of SSBs, including intentions to limit consumption of “beverages with added sugar” and intentions to limit consumption of the specific categories of SSBs sold in the trial store (e.g., “sodas,” “fruit drinks”). Questionnaires also assessed whether participants noticed the label applied to the SSBs (health warning or control) and four message reactions (i.e., responses to the trial labels): attention elicited by the label, cognitive elaboration (thinking about the label and thinking about the harms of SSB consumption), negative emotions elicited by the label (e.g., fear, regret), and anticipated social interactions about the label. Because the attention, elaboration, emotion, and social interactions items queried participants’ responses to their trial label (e.g., How much did the labels on the beverages make you feel anxious?), only participants who indicated noticing the trial label received these items. Among participants who reported they did not notice the label, researchers coded responses to these items with the lowest value. Additionally, the questionnaire assessed four SSB perceptions and attitudes: perceived amount of added sugar in SSBs sold in the trial store, perceived healthfulness of consuming beverages with added sugar, positive attitudes (appeal and coolness) toward SSBs sold in the trial store, and negative outcome expectations (i.e., disease risk perceptions) regarding consuming beverages with added sugar.

Questionnaires also assessed participants’ beliefs about the purpose of the study using an open-ended question presented before any other items. Researchers coded responses to this item to determine whether participants correctly guessed the purpose of the study (i.e., to assess the impact of SSB health warnings on purchase behavior).

Statistical Analysis

Power analyses used G*Power,35 version 3.1 to calculate sample size needs for detecting an effect of health warnings on SSB purchases using linear regression. Previous studies of SSB health warnings have examined purchase intentions (rather than actual purchases) as the primary outcome, finding medium19,20 and large effect sizes.21 To provide a conservative estimate of required sample size accounting for the intention–behavior gap, power analyses assumed a small standardized effect (Cohen’s f2 =0.02). Analyses indicated that the target enrollment of 400 adults would provide 80% power to detect this effect or larger, assuming α=0.05.

Analyses of trial outcomes included all randomized participants (intent-to-treat analyses). Analyses examined differences between trial arms in participant characteristics using chi-square tests and t-tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Analyses used a critical α=0.05 and two-tailed statistical tests. Analyses used Stata SE, version 15.1 in 2019.

Analyses examined the impact of trial arm on SSB calories purchased controlling for any participant characteristics found to differ between trial arms. Although the pre-analysis plan specified using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to examine SSB calories purchased, this outcome was zero-inflated, and a two-part model better fit the data (Akaike information criterion (AIC), two-part model: 3,332; OLS: 5,068). Thus, analyses of the primary outcome used a two-part model with logistic regression to examine probability of purchasing any SSB calories and OLS regression to examine amount of SSB calories purchased conditional on having purchased any SSB calories. Sensitivity analyses excluding participants who correctly identified the purpose of the study (n=18, 4.5% of the sample) revealed similar results, so subsequent analyses included all participants. To examine whether the effect of the health warnings on SSB purchases differed by participant characteristics, analyses added participant characteristics and their interaction with trial arm to separate models for each characteristic.

To examine secondary outcomes, analyses used two-part models for non-SSB calories (which were zero-inflated), OLS regression for all other continuous outcomes, and logistic regression for dichotomous outcomes, again controlling for participant characteristics that differed between trial arms. Though the pre-analysis plan specified using Poisson regression for count outcomes (i.e., number of SSBs purchased), the data were overdispersed, so these analyses instead used negative binomial regression.36 To account for potential heteroskedasticity, all models for continuous variables used robust SEs. Results report unadjusted point estimates (means, proportions) and adjusted differences (ADs) controlling for participant characteristics that differed between arms. Unadjusted differences were very similar (Appendix Table 2). No interim analyses were conducted. Except where noted, all outcomes and analyses described were prespecified in the trial’s Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan (available from http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03511937).

RESULTS

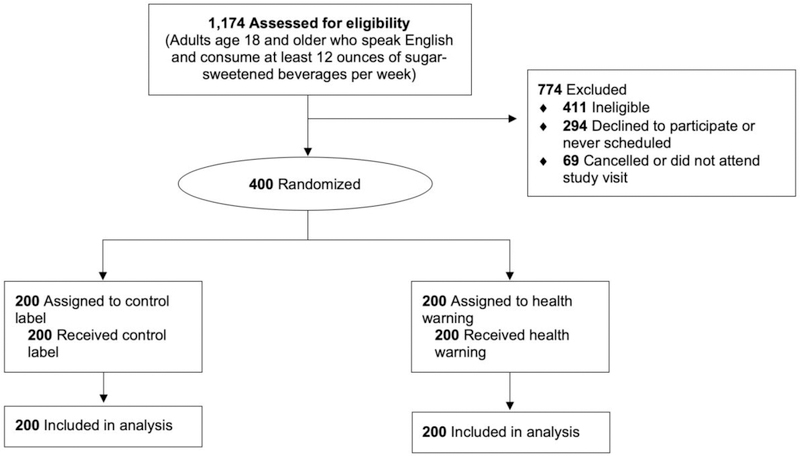

A total of 400 adult SSB consumers enrolled in the study. All received their allocated intervention and were included in analyses (Figure 2). The average age in the sample was 29.0 (SD=10.3) years. Participants were diverse: More than half were non-white; 10% identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual; and more than half had an annual household income <$50,000 (Table 1). Of the 11 conducted balance tests, two were statistically significant. Participants in the control arm were more likely than participants in the health warning arm to be Hispanic (p=0.004) and to have a BMI in the overweight/obese range (BMI ≥25 kg/m2, p=0.03).

Figure 2.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Trial Arm

| Characteristics | Control arm n=200 n (%) | Health warning arm n=200 n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| 18–29 | 125 (63) | 132 (66) |

| 30–39 | 47 (24) | 41 (21) |

| 40–54 | 22 (11) | 19 (10) |

| ≥55 | 6 (3) | 8 (4) |

| Mean (SD) | 29.0 (10.3) | 29.0 (10.5) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 83 (42) | 76 (38) |

| Female | 115 (58) | 121 (61) |

| Transgender or other | 2 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Gay, lesbian, or bisexual | 21 (11) | 20 (10) |

| Hispanic | 25 (13) | 9 (5) |

| Race | ||

| White | 87 (44) | 93 (47) |

| Black or African American | 46 (23) | 43 (22) |

| Asian | 47 (24) | 51 (26) |

| Other/multiraciala | 17 (9) | 12 (6) |

| Low education (some college or less)b | 47 (24) | 47 (24) |

| Limited health literacyc | 40 (20) | 34 (17) |

| Household income, annual | ||

| $0–$24,999 | 47 (24) | 49 (25) |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 61 (31) | 54 (27) |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 22 (11) | 34 (17) |

| ≥$75,000 | 69 (35) | 63 (32) |

| Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption | ||

| Low (≤60 oz/weekd) | 103 (52) | 100 (50) |

| High (>60 oz/weekd) | 97 (49) | 100 (50) |

| Overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) | 93 (47) | 72 (36) |

Note: Missing demographic data ranged from 0% to 1%. In the 11 balance tests conducted, two statistically significant differences between the health warning and control arm were observed: proportion Hispanic (p=0.004) and proportion overweight (p=0.03).

Includes participants who marked “other race,” American Indian/Native American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or who marked multiple races.

Educational attainment for participants ≤25 years (who may still be completing degrees) was assessed using mother’s or father’s educational attainment, whichever was higher.

“Possibility” or “high likelihood” of limited health literacy based on score on the Newest Vital Sign questionnaire.50

Sample median.

Participants in the control arm purchased an average of 143.2 (SE=9.7) calories from SSBs, the primary trial outcome (Table 2). Participants in the health warning arm purchased 109.9 (SE=9.5) calories from SSBs. In adjusted analyses, health warnings led to a reduction of –31.4 calories of SSBs purchased (95% CI= –57.9, –5.0). Unadjusted analyses yielded similar results (difference, –32.9 calories; 95% CI= –58.9, –7.0). The effect of SSB health warnings on SSB purchases did not differ by any of the ten examined participant characteristics (i.e., age, gender, sexual orientation, Hispanic ethnicity, race, educational attainment, income, health literacy, usual SSB intake, and overweight/obese status; p>0.20 for all interactions) (Appendix Table 3). Health warnings also led to lower likelihood of purchasing an SSB (64% vs 50%, AD= –13 percentage points, 95% CI= –23%, –4%]) and lower number of SSBs purchased (0.9 beverages vs 0.7 beverages, AD= –0.2 SSBs, 95% CI= –0.4, –0.1). Results were similar in unadjusted analyses (Appendix Table 2).

Table 2.

Impact of Sugar-sweetened Beverage Health Warnings on Purchase Behaviors and Psychological Outcomes, n=400 Adults

| Outcome | Control n=200 Unadjusted mean (SE) | Health warning n=200 Unadjusted mean (SE) | Adjusted impact of SSB health warninga (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase behaviors | ||||

| Calories purchased by source | ||||

| SSBs (primary outcome) | 143.2 (9.7) | 109.9 (9.5) | −31.4 (−57.9, −5.0) | 0.020* |

| Non-SSBsb | 32.9 (4.5) | 47.1 (5.5) | 12.5 (−1.6, 26.6) | 0.082 |

| Foodsb | 2,259.5 (75.6) | 2,208.7 (81.3) | −49.5 (−271.3, 172.3) | 0.661 |

| Total calories purchased | 2,435.6 (77.5) | 2,365.6 (82.9) | −69.4 (−295.5, 156.6) | 0.546 |

| Purchase of an SSB, % (N) | 64 (128) | 50 (100) | −13 (−23%, −4%) | 0.006** |

| Number of SSBs purchased | 0.9 (0.06) | 0.7 (0.06) | −0.2 (−0.4, −0.1) | 0.010* |

| Behavioral intentions | ||||

| Intentions to limit consumption of beverages with added sugarc | 4.7 (0.13) | 4.8 (0.13) | 0.2 (−0.2, 0.5) | 0.403 |

| Intentions to limit consumption of SSBs in trial storec | 5.0 (0.12) | 5.5 (0.10) | 0.4 (0.1, 0.8) | 0.005** |

| Responses to trial labels | ||||

| Noticed trial label, % (N) | 33 (65) | 75 (150) | 37 (32, 43) | <0.001*** |

| Attention to labeld,e | 1.5 (0.06) | 3.1 (0.11) | 1.7 (1.4, 1.9) | <0.001*** |

| Thinking about warning message/harmsd,e | 1.2 (0.04) | 2.3 (0.09) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) | <0.001*** |

| Negative emotions elicited by labeld,e | 1.1 (0.02) | 1.5 (0.05) | 0.4 (0.3, 0.5) | <0.001*** |

| Anticipated social interactions about labeld,e | 1.3 (0.05) | 2.2 (0.09) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | <0.001*** |

| SSB perceptions and attitudes | ||||

| Perceived amount of added sugar in SSBs in trial storef | 3.6 (0.02) | 3.6 (0.02) | 0.07 (−0.001, 0.13) | 0.055 |

| Perceived healthfulness of consuming SSBs in trial storec | 2.4 (0.06) | 2.3 (0.06) | −0.10 (−0.27, 0.07) | 0.258 |

| Positive product attitudes toward SSBs in trial storec | 4.1 (0.08) | 4.1 (0.07) | −0.09 (−0.30, 0.13) | 0.416 |

| Negative outcome expectations about beverages with added sugarc | 6.1 (0.07) | 6.2 (0.06) | 0.05 (−0.14, 0.24) | 0.609 |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Adjusted differences in predicted means (continuous or count outcomes) or predicted probabilities (dichotomous outcomes) between health warning and control arms.

Calories purchased from non-sugar-sweetened beverages and from foods were not registered as secondary outcomes.

Response scale for intentions, perceived healthfulness of SSB consumption, positive SSB product attitudes, and negative outcome expectations ranged from 1 to 7, with 7 indicating higher quantity or stronger endorsement.

Participants who indicated that they did not notice the trial label were not shown items about attention, cognitive elaboration, negative emotions, or anticipated social interactions; their responses to these items were coded with the lowest value.

Response scale for attention, thinking about warning message/harms, negative emotions, and social interactions ranged from 1 to 5, with 5 indicating higher quantity or stronger endorsement.

Response scale for perceived amount of added sugar ranged from 1 to 4, with 4 indicating higher quantity.

SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

The SSB health warnings led to higher intentions to limit consumption of the SSBs sold in the trial store (e.g., intentions to limit consumption of “sodas,” “fruit drinks”) (p=0.005), but intentions to limit consumption of “beverages with added sugar” did not differ between trial arms (p=0.403) (Table 2). Participants in the health warning arm were more likely to notice the trial label (p<0.001) and reported greater attention to the label (p<0.001). The health warning also led to more thinking about the trial label and harms of SSB consumption, higher levels of negative emotions, and higher anticipation of talking with others about the label (all p<0.001). Perceived amount of added sugar in SSBs, perceived healthfulness, positive product attitudes, and negative outcome expectations did not differ by trial arm.

To understand purchase behaviors more broadly, analyses also examined the impact of health warnings on calories purchased from foods, from non-SSBs, and from all sources (i.e., total calories from SSBs, non-SSBs, and foods) (Table 2). Only the latter, total calories from all sources, was pre-registered as a secondary outcome. Participants in the health warning arm purchased somewhat more calories from non-SSBs than participants in the control arm (driven almost entirely by higher juice purchases), although the difference was not significant (AD=12.5 calories, 95% CI= –1.6, 26.6). Trial arms did not differ on calories purchased from foods (AD= – 49.5 calories, 95% CI= –271.3, 172.3) or in total calories purchased from all sources (AD= –69.4, 95% CI= –295.5, 156.6).

DISCUSSION

This naturalistic RCT with 400 U.S. adults found that health warnings reduced SSB purchases. Consistent with previous studies,19,20,31 the effectiveness of SSB health warnings did not differ across diverse population groups, including racial/ethnic minorities as well as adults with limited health literacy, lower education, lower income, and an overweight/obese BMI. The observed reduction of 31 SSB calories per transaction represents a 22% decrease over the control arm and could have meaningful population-level health implications if sustained over time. For example, recent microsimulation studies37–39 have found that reducing average SSB intake by about 25 to 30 calories per day could lower obesity prevalence by 1.5 to 2.4% and Type 2 diabetes incidence by up to 2.6%.

These findings fill an important gap in research on SSB health warnings. Few studies of SSB health warnings have measured actual behavior, instead assessing hypothetical purchase intentions.19–21 Those that have measured behavioral outcomes either lacked a randomized design23 or displayed beverages and health warnings on a computer screen, not in a retail environment.24 RCTs in naturalistic, immersive settings like the laboratory store used in the present study have the benefit of providing both a controlled environment while also simulating many of the conditions consumers would experience in the real world if SSB health warning policies were implemented.

Experience with tobacco litigation suggests that this type of a study—an RCT examining a behavioral outcome—could be important in determining the legal fate of SSB warnings. The implementation of a 2009 law requiring pictorial cigarette warnings in the U.S. has been stalled since the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit struck down the Food and Drug Administration’s proposed warnings in R.J. Reynolds vs. FDA.40 The decision centered in part on the lack of causal evidence of behavioral impact of the proposed warnings: Despite substantial evidence of pictorial warnings’ benefits from observational studies with behavioral endpoints and randomized experiments with non-behavioral endpoints,34,41 the court asserted that the Food and Drug Administration had “not provided a shred of evidence” that pictorial warnings would reduce actual smoking rates.40 By examining a behavioral outcome using a randomized design, studies like the present one can help build an evidence base to inform SSB warning policymaking and potential litigation.

The weight loss benefits of reducing SSB consumption depend on the extent to which individuals compensate for decreased SSB consumption by increasing caloric intake from other sources.42,43 This trial provides some insights on compensatory behaviors. SSB health warnings induced a not-statistically-significant 12.5 calorie increase in purchases of non-SSBs (mostly juice), partially offsetting the reduction in SSB calories purchased. Trial arms did not differ on calories purchased from foods or in total calories purchased from all sources. This could be due to the large variance in these outcomes overwhelming the differences between trial arms. For example, the SD in total calories purchased (1,134 calories) was more than an order of magnitude larger than the impact of health warnings on this outcome (–69 calories). There remains debate about whether policies should narrowly target SSBs, or expand to include additional products.11,44,45 Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to more fully elucidate the effect of health warnings on calories purchased from different sources, particularly from caloric beverages not legally defined as “SSBs,” such as fruit juice.

Two previous studies have evaluated the impact of text SSB health warnings on real-stakes beverage purchases. In contrast to the present study, neither found that the text warnings reduced consumers’ SSB purchases.23,24 One possible explanation for the differing results is that the warnings tested in the studies used different designs. Previous work has found that front-of-package labels that describe health effects,31,46 are octagon-shaped,31,47 and use red to signal unhealthfulness31,47–49 may be more effective than labels without these characteristics. The warnings used in the present study used all three characteristics, whereas those tested previously each lacked one or more of these characteristics, and it may be that these design features are important for maximizing warnings’ behavioral impacts.

Few studies have examined how SSB health warnings exert their effects on behavior. The Tobacco Warnings Model32,34 proposes that warnings operate by increasing attention, which in turn elicits stronger negative emotions, more social interactions with others about the warning, more thinking about harms, and ultimately greater motivation for behavior change. The current study found support for this model. In this trial, SSB health warnings elicited more attention, stronger negative emotions, higher likelihood of social interactions, and more thinking about the harms of SSB consumption than control labels. Health warnings also increased participants’ intentions to limit consumption of the SSBs sold in the trial store. By contrast, there were no differences between trial arms in perceptions of added sugar content in SSBs, positive attitudes toward SSBs, or expectations that SSB consumption increases disease risk. These results stand in contrast to online studies reporting that SSB health warnings influence perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs about SSBs,19–21 but are consistent with studies of pictorial cigarette warnings that find little effect of warnings on attitudes or perceptions of disease risk.32,33

Limitations

Two key strengths of this study are the use of an RCT and the objective measurement of a behavioral outcome. Other strengths include the diverse sample of SSB consumers and the laboratory store setting that mimicked a true convenience store environment and displayed SSB health warnings on actual SSB containers. One limitation of this study is that participants had only a brief exposure to SSB health warnings. If SSB warning policies were implemented, consumers would see warnings every time they shopped for beverages. Donnelly and colleagues23 found that the impact of graphic SSB health warnings on purchases was consistent over a 2-week intervention period in their quasi-experiment, but effects beyond this timeframe remain unknown. Another limitation is that the naturalistic trial store had some differences from real stores, including that the store sold beverages off of the shelf instead of from a refrigerated display case. The SSB health warning labels also obscured the branding on some products; to control for this, researchers placed both the health warning and control labels in similar locations on SSB containers. Additionally, participants were aware that their purchases would be recorded and this knowledge may have influenced their behavior. However, purchases were recorded in both trial arms, and few participants correctly guessed the trial’s purpose, making it unlikely that knowledge of being assessed influenced the trial findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Five U.S. states have proposed but not yet implemented SSB health warning policies. Findings from this naturalistic RCT suggest that SSB health warning policies could reduce SSB purchases, providing timely information for policymakers as they seek to identify strategies to reduce overconsumption of SSBs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Chulpan Khristamova for exceptional management of the Fuqua Behavioral Lab; Carmen Prestemon, Jane Schmid, and Dana Manning for assistance with data collection; Emily Busey for assistance with graphic design; Natalie R. Smith for assistance with randomization and data preparation; and Edwin B. Fisher and Leah Frerichs for feedback on study design and the manuscript.

The research presented in this paper is that of the authors and does not reflect official policy of the NIH.

This project was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH, through Grant Award Number UL1TR002489 (internal grant 2KR951708 to AHG and LST), and through the University of North Carolina Family Medicine Innovations Award (no award number, to AHG and LMR). AHG received training support from the NIH (CPC P2C HD050924, T32 HD007168) and the University of North Carolina Royster Society of Fellows. AHG and LST received general support from the NIH (CPC P2C HD050924). MGH received training support from the NIH (T32 CA057726). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The study was approved by the University of North Carolina IRB (#17–3375); first approval, January 30, 2018; renewal, January 23, 2019.

Footnotes

Author roles were as follows: AHG conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and oversaw all aspects of the study. LST and MGH provided input on study design and measures. SDG and LMR provided input on study design. NTB provided expert guidance on each stage of the project, including study design, measure development, and data analysis and interpretation. All authors provided critical feedback on manuscript drafts and approved the final manuscript.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bleich SN, Vercammen KA, Koma JW, Li Z. Trends in beverage consumption among children and adults, 2003–2014. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26(2):432–441. 10.1002/oby.22056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(8):933–944. 10.1161/cir.0b013e31820a55f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.HHS, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020. 8th edition. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/. Published 2015. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- 4.Malik V, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):1084–1102. 10.3945/ajcn.113.058362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després J-P, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2010;121(11):1356–1364. 10.1161/circulationaha.109.876185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imamura F, O’Connor L, Ye Z, et al. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. BMJ. 2015;351:h3576 10.1136/bmj.h3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu F Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev. 2013;14(8):606–619. 10.1111/obr.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vargas Garcia E, Evans C, Sykes Prestwich A Muskett B, Hooson J, Cade J. Interventions to reduce consumption of sugar sweetened beverages or increase water intake: evidence from a systematic review and meta analysis. Obes Rev. 2017;18(11):1350–1363. 10.1111/obr.12580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804–814. 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberto CA, Swinburn B, Hawkes C, et al. Patchy progress on obesity prevention: emerging examples, entrenched barriers, and new thinking. Lancet. 2015;385(9985):2400–2409. 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61744-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawkes C, Smith TG, Jewell J, et al. Smart food policies for obesity prevention. Lancet. 2015;385(9985):2410–2421. 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61745-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Office of the Surgeon General, CDC, NIH. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General; 2001. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44206/. Accessed January 17, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monning B Sugar-Sweetened Beverages: Safety Warnings. http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200SB347. Published 2019. Accessed February 27, 2019.

- 14.Robinson J Concerning Mitigation of the Adverse Impacts of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages. http://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=2798&Year=2016. Published 2016. Accessed June 24, 2019.

- 15.Kobayashi B, Lopresti M, Morikawa D. Relating to Health. www.capitol.hawaii.gov/measure_indiv.aspx?billtype=HB&billnumber=1209&year=2017. Published 2017. Accessed June 24, 2019.

- 16.Stevens T, Carr S. An Act Related to Health and Safety Warnings on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages. https://legislature.vermont.gov/bill/status/2018/H.433. Published 2017. Accessed July 3, 2019.

- 17.Rivera G Requires Sugar-Sweetened Beverages to Be Labeled with a Safety Warning. www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2017/S162. Published 2017. Accessed June 24, 2019.

- 18.Falbe J, Madsen K. Growing momentum for sugar-sweetened beverage campaigns and policies: costs and considerations. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):835–838. 10.2105/ajph.2017.303805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberto CA, Wong D, Musicus A, Hammond D. The influence of sugar-sweetened beverage health warning labels on parents’ choices. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20153185 10.1542/peds.2015-3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.VanEpps EM, Roberto CA. The influence of sugar-sweetened beverage warnings: a randomized trial of adolescents’ choices and beliefs. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(5):664–672. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bollard T, Maubach N, Walker N, Mhurchu CN. Effects of plain packaging, warning labels, and taxes on young people’s predicted sugar-sweetened beverage pan experimental study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:95 10.1186/s12966-016-0421-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webb TL, Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(2):249–268. 10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donnelly G, Zatz L, Svirsky D, John L. The effect of graphic warnings on sugary-drink purchasing. Psychol Sci. 2018;29(8):1321–1333. 10.1177/0956797618766361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acton R, Hammond D. The impact of price and nutrition labelling on sugary drink purchases: results from an experimental marketplace study. Appetite. 2018;121:129–137. 10.1016/j.appet.2017.11.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedrick VE, Savla J, Comber DL, et al. Development of a brief questionnaire to assess habitual beverage intake (BEVQ-15): sugar-sweetened beverages and total beverage energy intake. J Am Diet Assoc. 2012;112(6):840–849. 10.1016/j.jand.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shadel WG, Martino SC, Setodji CM, et al. Hiding the tobacco power wall reduces cigarette smoking risk in adolescents: using an experimental convenience store to assess tobacco regulatory options at retail point-of-sale. Tob Control. 2016;25(6):679–684. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shadel WG, Martino SC, Setodji C, et al. Placing antismoking graphic warning posters at retail point-of-sale locations increases some adolescents’ susceptibility to future smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;21(2):220–226. 10.1093/ntr/ntx239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng SW, Popkin BM. Monitoring foods and nutrients sold and consumed in the United States: dynamics and challenges. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(1):41–45. 10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kit BK, Fakhouri TH, Park S, Nielsen SJ, Ogden CL. Trends in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among youth and adults in the United States: 1999–2010. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(1):180–188. 10.3945/ajcn.112.057943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bleich SN, Wang YC, Wang Y, Gortmaker SL. Increasing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among U.S. adults: 1988–1994 to 1999–2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;89(1):372–381. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grummon AH, Hall MG, Taillie LS, Brewer NT. How should sugar-sweetened beverage health warnings be designed? A randomized experiment. Prev Med. 2019;121:158–166. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brewer N, Parada H Jr., Hall M, Boynton M, Noar S, Ribisl K. Understanding why pictorial cigarette pack warnings increase quit attempts. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(3):232–243. 10.1093/abm/kay032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brewer NT, Hall MG, Noar SM, et al. Effect of pictorial cigarette pack warnings on changes in smoking behavior: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):905–912. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noar SM, Hall MG, Francis DB, Ribisl KM, Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Pictorial cigarette pack warnings: a meta-analysis of experimental studies. Tob Control. 2015;25(3):341–354. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–191. 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wooldridge J Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. 5th ed. Mason, OH: South-Western, Cengage Learning; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long MW, Gortmaker SL, Ward ZJ, et al. Cost effectiveness of a sugar-sweetened beverage excise tax in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(1):112–123. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Coxson P, Shen Y-M, Goldman L, Bibbins-Domingo K. A penny-per-ounce tax on sugar-sweetened beverages would cut health and cost burdens of diabetes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(1):199–207. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Basu S, Seligman HK, Gardner C, Bhattacharya J. Ending SNAP subsidies for sugar-sweetened beverages could reduce obesity and type 2 diabetes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(6):1032–1039. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. Food and Drug Admin. U.S. Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noar SM, Francis DB, Bridges C, Sontag JM, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. The impact of strengthening cigarette pack warnings: systematic review of longitudinal observational studies. Soc Sci Med. 2016;164:118–129. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edwards RD. Commentary: soda taxes, obesity, and the shifty behavior of consumers. Prev Med. 2011;52(6):417–418. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall KD, Sacks G, Chandramohan D, et al. Quantification of the effect of energy imbalance on bodyweight. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):826–837. 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60812-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gill JM, Sattar N. Fruit juice: just another sugary drink? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(6):444–446. 10.1016/s2213-8587(14)70013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arsenault BJ, Lamarche B, Despres J-P. Targeting overconsumption of sugar-sweetened beverages vs. overall poor diet quality for cardiometabolic diseases risk prevention: place your bets! Nutrients. 2017;9(6):600 10.3390/nu9060600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baig SA, Byron MJ, Boynton MH, Brewer NT, Ribisl KM. Communicating about cigarette smoke constituents: an experimental comparison of two messaging strategies. J Behav Med. 2017;40(2):352–359. 10.1007/s10865-016-9795-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cabrera M, Machín L, Arrúa A, et al. Nutrition warnings as front-of-pack labels: influence of design features on healthfulness perception and attentional capture. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(18):3360–3371. 10.1017/s136898001700249x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawley KL, Roberto CA, Bragg MA, Liu PJ, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. The science on front-of-package food labels. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(3):430–439. 10.1017/s1368980012000754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cecchini M, Warin L. Impact of food labelling systems on food choices and eating behaviours: a systematic review and meta analysis of randomized studies. Obes Rev. 2016;17(3):201–210. 10.1111/obr.12364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):514–522. 10.1370/afm.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.