Abstract

Lymphoepithelioma-like intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (LEL-ICC) is an uncommon lesion. Less than 100 cases of hepatic LELC, including IEL-HCC (hepatocellular carcinoma) and IEL-ICC, have been described, and the understanding of the LELC is very limited. We report the case of a 75-year-old woman with LEL-ICC. She complained of finding a lesion located in the left lateral liver during her last check-up 2 years ago. The contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a low-density mass located in the left lateral liver with an estimated magnitude of 20×16 mm. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated two T2 high-signal intensity foci in the left lateral liver, with similar size and signal manifestation in the arterial and portal venous phases. The patient underwent laparoscopic left lateral hepatectomy. The postoperative pathological and immunohistochemical examination findings allowed for the definitive diagnosis. A literature review indicated that a geriatric Asian female with a single lesion located in the liver should consider the possibility of LEL-ICC. An Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection might play a crucial role in the tumorigenesis of LEL-ICC, and surgical resection was the first choice for treating LEL-ICC.

Keywords: Lymphoepithelioma-like cholangiocarcinoma; liver, lesion; Epstein-Barr virus (EBV); literature review

Introduction

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC) is a rare malignancy and was first described in the nasopharynx in 1982, which is composed of undifferentiated epithelial cells with prominent lymphoid infiltration (1,2). Characterized by similar morphological features, this unique tumor has been identified in various locations, including the salivary glands, lungs, thymus, gastrointestinal tract, and urinary tract (3). LELC being found in the liver is extremely rare and can be divided into two types: lymphoepithelioma-like hepatocellular carcinoma (LEL-HCC) and lymphoepithelioma-like intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (LEL-ICC). The occurrence of hepatic LELC might result from a unique model of the immune response against the liver tumor, and in most cases (4), the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection was considered to play a crucial role in the carcinogenesis of LELC. Due to the lack of specific manifestations regarding the imaging findings and laboratory test results, the diagnosis of LELC is difficult to establish without post-operative histopathologic and immunohistochemical examinations. To the best of our knowledge, less than 100 cases of hepatic LELC, including IEL-HCC and IEL-ICC, have thus far been described, and the understanding of LELC is extremely limited. Thus, more reports are needed to describe the comprehensive features of hepatic LELC. Herein, we describe a case of LEL-ICC with an EBV infection in a 75-year-old Asian female, who received laparoscopic left lateral hepatectomy.

Case presentation

A 75-year-old female came to the out-patient department of the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, and complained of a lesion found in her left lateral liver during her last check-up 2 years ago. No further diagnosis and treatment were adopted at that time. Further inquiry revealed no specific symptoms and a history of viral hepatitis. Physical examinations discovered no abnormality. No elevation of tumor markers, including α-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cancer antigen 125 (CA125), and CA-19-9. Hepatitis virus markers were all negative, and liver function test was normal. Two weeks ago, she went to the local hospital for a routine check-up and received contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT). The lesion in the liver was noted, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed for further diagnosis.

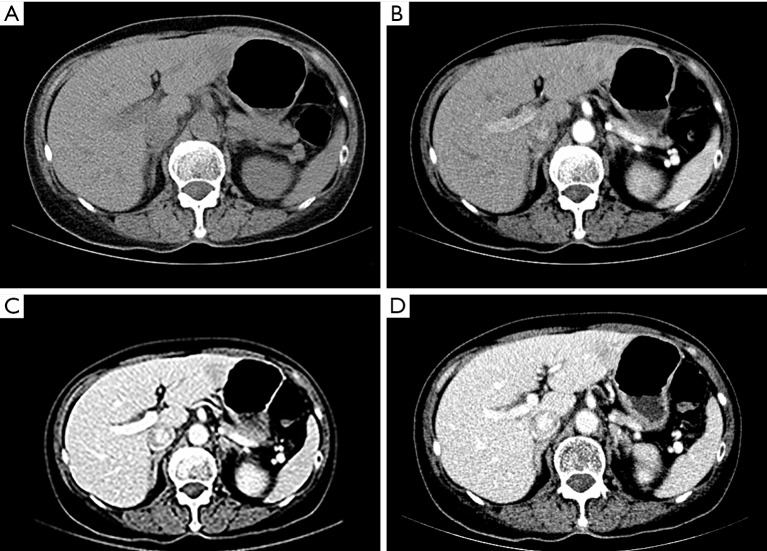

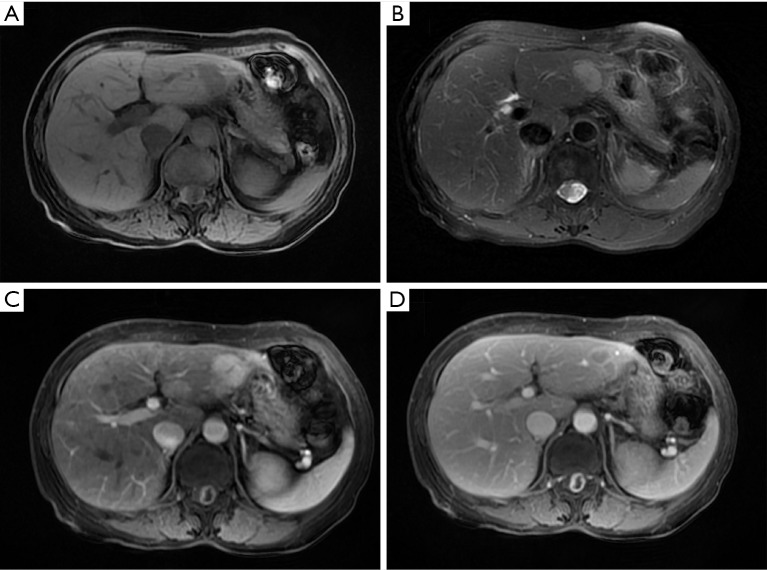

The CT scan revealed a low-density mass located in the left lateral liver with an estimated magnitude of 20 mm × 16 mm; a vague margin was also observed in the CT scan (Figure 1A). The mass showed mild-median signal enhancement in the arterial phase and a faded signal in the portal venous and delayed phases (Figure 1B,C,D). Another low-density lesion with an estimated magnitude of 13 mm × 19 mm was located in the left lateral liver. The lesion showed partial signal enhancement in the arterial phase and was further enhanced in the portal venous phase. No other abnormalities were noted. MRI demonstrated two T1 low signal intensity foci (Figure 2A) and T2 high-signal intensity foci (Figure 2B) in the left lateral liver. A similar size and signal manifestation in the arterial and portal venous phases (Figure 2C,D) were observed in MRI, as in CT scan. Under the assumption of an HCC diagnosis, the patient underwent laparoscopic left lateral hepatectomy. The operation lasted for 1.5 hours, and the intra-operative blood loss was about 200 mL. The post-operative recovery was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 8. During the routine follow-up 1 and 3 months after surgery, no evidence of recurrence was noted, and the liver function of the patient remained normal.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography before surgery. A low-density mass located in left lateral liver with an estimated magnitude of 20 mm × 16 mm and a vague margin was also observed in the CT scan. The mass showed mild-median signal enhancement in arterial phase and faded signal in portal venous and delayed phases. (A) scan phase; (B) arterial phase; (C) portal venous phase; (D) delayed phase. CT, computed tomography.

Figure 2.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging before surgery. MRI demonstrated two T2 high signal intensity and T1 low signal intensity foci in the left lateral liver. The lesion showed enhancement on arterial phase and faded signal on portal and delayed phases. (A) T1-weighted image; (B) T2-weighted image; (C) arterial phase; (D) portal venous phase. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

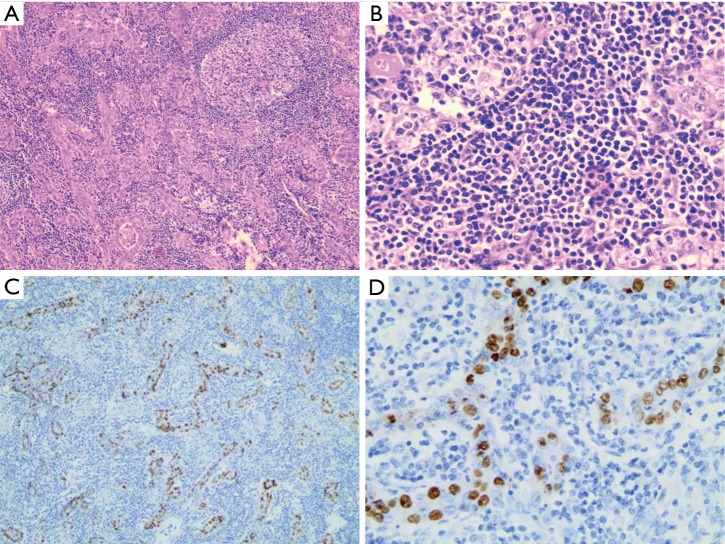

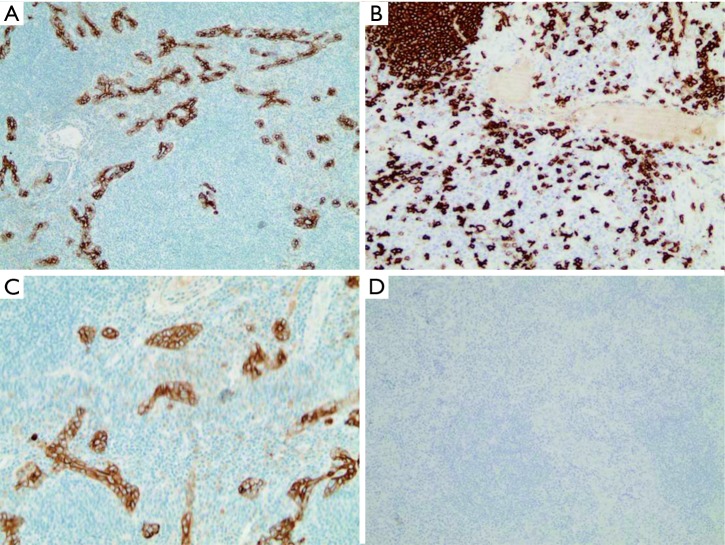

Gross examination showed two gray foci measuring 15×15 and 14×11 mm in the resected segment. Microscopically, the larger lesion composed of undifferentiated epithelial cells with vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and significant lymphocytic infiltration (Figure 3A,B). EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) in situ hybridization was performed and found positive in tumor tissues (Figure 3C,D). Immunohistochemical examination revealed positive in CK (pan), EMA, CD3, CD20, Ki-67, and negative in P63, CK19, CK5/6 (Figure 4). The tumor-free surgical margin was at least 10 mm. All features fulfilled the diagnosis of LEL-ICC. The smaller lesion was confirmed to be a cavernous hepatic hemangioma.

Figure 3.

Pathological and EBER in situ hybridization examinations after surgery. Microscopically, the larger lesion composed of undifferentiated epithelial cells with vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli and significant lymphocytic infiltration. EBER-encoded RNA was found positive in tumor tissues. (A) HE ×100; (B) HE ×400; (C) EBER in situ hybridization ×100; (D) EBER in situ hybridization ×400. EBER, EBV-encoded RNA; HE, hematoxylin and eosin.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical examinations after surgery. Microscopically, CK (pan) and CD 20 were confirmed as positive, while CK19 and CK5/9 were negative in tumor tissues. (A) CK (pan) ×100; (B) CD 20 ×200; (C) CK19 ×200; (D) CK5/9 ×100.

Discussion

LELC is defined as a tumor composed of undifferentiated epithelial cells with prominent lymphoid infiltration (2). So far, it has been reported in the salivary glands (5), esophagus (6), stomach (7), trachea (8), lungs (9), colon (10), urinary bladder (11), uterine cervix (12), ovaries (13), and other locations. Hepatic LEL is extremely rare and usually found by accident. To the best of our knowledge, 67 cases of LEL-HCC, and 25 cases of LEL-ICC (Table 1) have been reported in the literature (2,14-17). A summary of the previously reported cases of LEL-ICC and the present case are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the patients is 55 years old (range, 19–79 years old), with 69.2% (18/26) being female and 88.5% (23/26) being Asian. The lesions of LEL-ICC were usually single (92.3%, 24/26) ranging from 15 to 120 mm, and in most cases, were larger than 20 mm.

Table 1. Reported cases of lymphoepithelioma-like cholangiocarcinoma (Data statistics as 2017/4/15, N=26).

| No | Reference | Age | Sex | Race | Symptom | Number of lesion | Size (mm) | Site | HBV | HCV | EBV | Follow-up (mouth) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hsu | 47 | F | Asian | Abdominal fullness | 2 | 120 | L | N | N | P | 48 | DOD |

| 2 | Kim | 64 | M | Asian | Incidental finding | 1 | 20 | R | N | P | N | NA | NA |

| 3 | Ortiz | 19 | F | White | Abdominal fullness | 1 | 55 | L | N | N | P | 44 | DOD |

| 4 | Jeng | 42 | M | Asian | Incidental finding | 1 | 30 | R | N | N | P | 84 | AWOD |

| 5 | 67 | F | Asian | Incidental finding | 1 | 30 | L | N | N | P | 7 | AWOD | |

| 6 | 50 | M | Asian | Vague epigastric pain | 1 | 40 | R | N | N | P | 16 | AWOD | |

| 7 | 50 | F | Asian | Incidental finding | 1 | 40 | R | N | N | P | 2 | AWOD | |

| 8 | Chen | 67 | F | Asian | Abdominal pain | 1 | 50 | R | N | N | P | <1 | POD |

| 9 | 41 | M | Asian | Abdominal pain | 1 | 30 | L | P | N | N | 8 | AWOD | |

| 10 | Szekely | 61 | M | NA | Incidental finding | 1 | 60 | NA | N | N | N | 11 | AWOD |

| 11 | Huang | 60 | F | Asian | Incidental finding | 1 | 35 | R | N | N | P | 24 | AWOD |

| 12 | Adachi | 64 | M | Asian | Fever | 1 | 52 | L | N | N | N | 3 | AWOD |

| 13 | Henderson-Jackson | 63 | F | Asian | Right-sided flank and back pain | 1 | 40 | R | N | N | P | 6 | AWOD |

| 14 | Hur | 57 | F | Asian | Incidental finding | 1 | 20 | R | N | N | N | 60 | AWOD |

| 15 | Lee | 79 | M | Asian | Incidental finding | 2 | 35 | L | P | N | N | 54 | AWOD |

| 16 | Chan | 53 | F | Asian | Incidental finding | 1 | 16 | R | P | N | P | 165 | AWOD |

| 17 | 40 | F | Asian | Incidental finding | 1 | 75 | R | P | N | P | 56 | AWD | |

| 18 | 57 | F | Asian | Non-painful vague And abdominal mass | 1 | 71 | L | N | N | P | 128 | AWOD | |

| 19 | 56 | F | Asian | Dyspepsia and reflux symptoms | 1 | 60 | L | N | N | P | 69 | DOD | |

| 20 | 59 | F | Asian | Incidental finding | 1 | 60 | L | P | N | P | 72 | AWOD | |

| 21 | 45 | F | Asian | Biliary colic | 1 | 30 | L | N | N | P | 71 | AWD | |

| 22 | 57 | F | Asian | Incidental finding | 1 | 30 | R | N | N | P | 58 | AWOD | |

| 23 | Liao | 35 | F | NA | Incidental finding | 1 | 16 | L | P | N | P | NA | NA |

| 24 | Aosasa | 65 | F | NA | Incidental finding | 1 | 64 | C | N | P | N | 20 | AWOD |

| 25 | Labgaa | 58 | M | Asian | Incidental finding | 1 | 22 | L | P | N | P | 61 | AWOD |

| 26 | This case | 75 | F | Asian | Incidental finding | 1 | 15 | L | N | N | P | 3 | AWOD |

F, female; M, male; NA, not available; L, lift lobe; R, right lobe; C, Caudate lobe; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; P, positive; N, negative; AWD, alive with disease; AWOD, alive without disease; DOD, died of disease; POD, postoperative dead.

The LELC is considered to be strongly associated with EBV infection (17). Among the 26 cases, 19 (73.1%) patients were EBV positive, and only 3% of LEL-HCC was confirmed to be infected with EBV (2). This finding indicates that EBV might play a crucial role in the tumorigenesis of LEL-ICC, which might result from the immune response caused by EBV infection. In LEL-ICC with EBV infection, the infiltrating lymphocytes produced several cytokines and chemokines. These lymphocytes do not control the tumor growth but, conversely, promote the progression of the tumor. Further molecular changes associated with EBV infection in LEL-ICC might exist and needed further clarification. However, Adachi stated that there were no obvious histopathologic differences between EBV-positive and EBV-negative LEL-ICC (14). Therefore, due to the rarity of LEL-ICC, the association between LEL-ICC and EBV is still controversial and inconclusive.

As for other viruses, like the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), only 26.9% (7 of 26) and 7.7% (2 of 26) patients were HBV and HCV positive, respectively. This low incidence of HBV and HCV infection suggests that these two viruses may not be significant factors in the pathogenesis of LEL-ICC. However, further study is still needed to confirm this hypothesis.

LELC had a better prognosis than other neoplasms in the stomach and lungs (17). In patients diagnosed with LEL-ICC, the 5-year survival rate was 100% and 13.2% in classical cholangiocarcinomas (16). Radical treatment contributed to the prognosis of LEL-ICC. In all cases reported, as, in ours, surgical resection was the sole choice of treatment. There is as yet no consensus on the standardized treatment protocol for LELC. However, postoperative radiotherapy, postoperative chemotherapy, or targeted therapy was rarely adopted. Lee reported a patient with lymph node metastasis who underwent postoperative radiation and was still alive without recurrence 54 months after the surgery (15). A similar case was introduced by Aosasa et al. and the patient was alive without recurrence more than 20 months after the surgery and post-operative radiation (17). Nevertheless, these promising results have still not been confirmed to be a result of post-operative radiation due to the commonly positive prognosis of LEL-ICC. Therefore, adjuvant therapies after surgery still needed to be adopted.

In the present report, we described a rare case of LEL-ICC associated with EBV infection in a geriatric Asian female. The patient received laparoscopic left lateral hepatectomy based on the clinical diagnosis of HCC and was found to be LEL-ICC after histopathologic and immunohistochemical examinations. A literature review indicated that a geriatric Asian female with a single lesion located in the liver should consider the possibility of LEL-ICC. An EBV infection might play a crucial role in the tumorigenesis of LEL-ICC, and surgical resection was still the first choice for treating LEL-ICC. The favorable prognosis could be generally achieved after radical surgery, and post-operative adjuvant therapies should be adopted prudently.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Public Welfare Technology Research Project of Zhejiang Province (No. LGD19C040006), the Medical Health Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Provincial (No.2 016KYB083), the General Research Project of the Zhejiang Provincial Education Department (No. Y201840044), and the Clinical Medical Innovation Center of Precision Diagnosis and Treatment for Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Disease of Zhejiang University (No. 2017-02-06).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All participants had signed written informed consent. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, China, in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki (committee’s reference number: 2017-388). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Applebaum EL, Mantravadi P, Haas R. Lymphoepithelioma of the nasopharynx. Laryngoscope 1982;92:510-4. 10.1288/00005537-198205000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Labgaa I, Stueck A, Ward SC. Lymphoepithelioma-Like Carcinoma in Liver. Am J Pathol 2017;187:1438-44. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solinas A, Calvisi DF. Lessons from rare tumors: hepatic lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:3472-9. 10.3748/wjg.v21.i12.3472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang JK, Jin YW, Hu HJ, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report and brief review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e9416. 10.1097/MD.0000000000009416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao W, Deng N, Gao X, et al. Primary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of salivary glands: a clinicopathological study of 21 cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014;7:7951-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khokhar N, Nasir H, Amir M, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-Like Carcinoma of the Esophagus: A Rare Tumor. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2017;27:S114-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong X, Zhao J, Sun Z. Lymphoepithelioma-Like Gastric Carcinoma Misdiagnosed as a Submucosal Tumor. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:e87. 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi H, Harada M, Ito T, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the trachea. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;13:191-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie M, Wu X, Wang F, et al. Clinical Significance of Plasma Epstein-Barr Virus DNA in Pulmonary Lymphoepithelioma-like Carcinoma (LELC) Patients. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:218-27. 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Díaz Del Arco C, Esteban Collazo F, Fernández Aceñero MJ. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the large intestine: A case report and literature review. Rev Esp Patol 2018;51:18-22. 10.1016/j.patol.2017.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang AW, Pooli A, Lele SM, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like, a variant of urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a case report and systematic review for optimal treatment modality for disease-free survival. BMC Urol 2017;17:34. 10.1186/s12894-017-0224-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yun HS, Lee SK, Yoon G, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Obstet Gynecol Sci 2017;60:118-23. 10.5468/ogs.2017.60.1.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ambrosio MR, Rocca BJ, Onorati M, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the ovary. Int J Surg Pathol 2011;19:514-7. 10.1177/1066896909354336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adachi S, Morimoto O, Kobayashi T. Lymphoepithelioma-like cholangiocarcinoma not associated with EBV. Pathol Int 2008;58:69-74. 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02192.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee W. Intrahepatic lymphoepithelioma-like cholangiocarcinoma not associated with epstein-barr virus: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 2011;4:68-73. 10.1159/000324485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan AW, Tong JH, Sung MY, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoepithelioma-like cholangiocarcinoma: a rare variant of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with favourable outcome. Histopathology 2014;65:674-83. 10.1111/his.12455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aosasa S, Maejima T, Kimura A, et al. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma With Lymphoepithelioma-like Carcinoma Components Not Associated With Epstein-Barr Virus: Report of a Case. Int Surg 2015;100:689-95. 10.9738/INTSURG-D-14-00117.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]