Bees are important insect pollinators that may encounter environmental pollution when foraging upon plants grown in contaminated areas. Despite the pervasiveness of pollution, little is known about the effects of these toxicants on honey bee metabolism and their symbiotic microbiomes. Here, we investigated the impact of selenate and cadmium exposure on the gut microbiome and metabolome of honey bees. We found that exposure to these chemicals subtly altered the overall composition of the bees’ microbiome and metabolome and that exposure to toxicants may negatively impact both host and microbe. As the microbiome of animals can reduce mortality upon metal or metalloid challenge, we grew bee-associated bacteria in media spiked with selenate or cadmium. We show that some bacteria can remove these toxicants from their media in vitro and suggest that bacteria may reduce metal burden in their hosts.

KEYWORDS: Gilliamella, Lactobacillus, Snodgrassella, honey bee, toxicants

ABSTRACT

Honey bees are important insect pollinators used heavily in agriculture and can be found in diverse environments. Bees may encounter toxicants such as cadmium and selenate by foraging on plants growing in contaminated areas, which can result in negative health effects. Honey bees are known to have a simple and consistent microbiome that conveys many benefits to the host, and toxicant exposure may impact this symbiotic microbial community. We used 16S rRNA gene sequencing to assay the effects that sublethal cadmium and selenate treatments had over 7 days and found that both treatments significantly but subtly altered the composition of the bee microbiome. Next, we exposed bees to cadmium and selenate and then used untargeted liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) metabolomics to show that chemical exposure changed the bees’ metabolite profiles and that compounds which may be involved in detoxification, proteolysis, and lipolysis were more abundant in treatments. Finally, we exposed several strains of bee-associated bacteria in liquid culture and found that each strain removed cadmium from its medium but that only Lactobacillus Firm-5 microbes assimilated selenate, indicating the possibility that these microbes may reduce the metal and metalloid burden on their host. Overall, our report shows that metal and metalloid exposure can affect the honey bee microbiome and metabolome and that strains of bee-associated bacteria can bioaccumulate these toxicants.

IMPORTANCE Bees are important insect pollinators that may encounter environmental pollution when foraging upon plants grown in contaminated areas. Despite the pervasiveness of pollution, little is known about the effects of these toxicants on honey bee metabolism and their symbiotic microbiomes. Here, we investigated the impact of selenate and cadmium exposure on the gut microbiome and metabolome of honey bees. We found that exposure to these chemicals subtly altered the overall composition of the bees’ microbiome and metabolome and that exposure to toxicants may negatively impact both host and microbe. As the microbiome of animals can reduce mortality upon metal or metalloid challenge, we grew bee-associated bacteria in media spiked with selenate or cadmium. We show that some bacteria can remove these toxicants from their media in vitro and suggest that bacteria may reduce metal burden in their hosts.

INTRODUCTION

Pollination services provided by bees are critical to agricultural crop production and native plant fitness. These insects are responsible for increasing the yield of over half of food crops and for benefiting a wide variety of natural flora (1, 2). Of the pollinating insects, European honey bees (Apis mellifera) are the most intensively used species of bee in agriculture and contribute to billions of dollars in food production in the United States alone (3). Along with other species, bee populations are declining around the world, most likely due to a combination of disease, pesticides, and land use change resulting in a lack of floral forage (4). Relatively unstudied stressors include the metals and metalloids that are harmful to bees and that can affect their overall health when bees forage on plants grown in contaminated areas (5, 6). As bees may encounter various pollutants across environments (7), the capacity for diverse environmental stressors to affect bee health needs to be understood and mitigated.

Heavy metal and metalloid contamination can be found in industrialized areas around the world (5). Here, we chose to study cadmium (Cd) and selenium (Se) due to their importance in agricultural and industrialized areas. Cadmium is a nonessential toxic heavy metal that is deposited near operational locations of industries such as mining and battery production (8) and has been found in croplands (9). Selenate is an ionic form of selenium that is found in soils near operational locations of such industries as glass making and ink production or is deposited in naturally seleniferous agricultural soils (10). As mentioned above, bees may contact metals and metalloids when foraging on plants growing in polluted areas (11, 12). Plants can translocate toxicants from the soil into their pollen and nectar, which bees then forage upon and bring back to their colonies (5). The potential for plants to accumulate metals and metalloids varies widely. For example, flowers of the hyperaccumulator plant Stanleya pinnata have been found to contain over 2,000 mg selenate/kg of plant weight (13), and partridge pea pollen was shown to accumulate over 4,000 mg cadmium/kg in greenhouse experiments (14). In contrast, radishes grown in high concentrations of lead did not accumulate the metal in their flowers (11). Likewise, while the levels of accumulation of these toxicants under natural conditions are largely unknown, selenium and cadmium have been found in bee products (up to 0.83 mg/kg and 4.23 mg/kg, respectively) and in whole bees (up to 1.82 mg/kg and 15.81 mg/kg, respectively) in contaminated areas (15, 16), indicating that transmission of these compounds occurs. As the concentrations of cadmium or selenate that have been measured in flowers and bee products are near or above the levels shown to increase larval and pupal mortality and reduce the larval growth rate and the honey bee colony worker population (5, 17), bees living in contaminated areas are likely more stressed and less healthy than those living in pristine areas. Bees often forage regardless of the metallic content of nectar and pollen, as bees freely forage on plants grown in selenate-contaminated soil (12) and on aluminum-containing nectar (18). In contrast, bumble bees tend to avoid nectar spiked with nickel (18), indicating that bees are able to detect some metals, so the ability of bees to detect metals and metalloids warrants further study.

Honey bees harbor a simple and distinct microbiome that is largely consistent in all colonies worldwide (19, 20). This symbiotic relationship between microbe and host is thought to be the result of a long-lasting relationship (21) that is largely maintained through contact between colonymates (22). The bee microbiome is involved in many aspects of host health, including metabolization of toxic sugars (23), resistance to trypanosomes (24–26), bacterial pathogen defense (27), stimulation of the immune system (28), and weight gain in adult bees (29). Due to the importance of the bee microbiome, one would expect reduced vitality under conditions in which this symbiotic microbiome is absent or in a state of dysbiosis (30). Indeed, when the microbiome of social bees is perturbed or absent, bees are more susceptible to Nosema and Serratia infection (31–33), gut scab formation caused by Frischella perrara (34), and selenate toxicity (35).

The interaction between environmental metal pollution and animal microbiomes is an emerging field of study (36, 37). There has been a fair amount of investigation into the interactions between cadmium and animal microbiomes (reviewed in reference 38). Previous work has shown that cadmium exposure significantly alters the microbiome of rats (39), mice (40–42), earthworms (43), and spiders (44). To date, no research has investigated these interactions in any insect species. Much less is known about the effects of selenium on gut microbial communities, but subtle alterations in these microbe populations have been revealed by previous studies performed under conditions of exposure to selenium ions in mice (45, 46) and through our work with bumble bees (35). In light of the effects of toxicant exposure on the microbiome, research is now being conducted on the ability of this microbial community to protect its host against environmental exposures. For example, it was recently shown that the gut microbiome protects against arsenic challenge in mice (47), selenate toxicity in bumble bees (35), and lead or chromium exposure in chironomids (48). Likewise, various Lactobacillus spp. can accumulate copper (49), cadmium (50–52), aluminum (53), and chromium (54), which suggests that members of this genus have the potential to be administered as probiotics to reduce metal burden in the host.

While mortality in bees is relatively straightforward to assess, sublethal doses of toxicants can alter bee physiology in subtler ways. For example, at the organismal level, exposure to manganese increases bee foraging time (6), exposure to copper affects feeding behavior (55), and exposure to imidacloprid alters nest behaviors (56). Metabolically, exposing bees to heavy metals increases detoxification enzyme activity (57, 58) and metallothionein-like protein levels (59) while affecting their overall redox system (60), which may indicate a general response to toxic metal stress. Similarly, metals have been shown to hamper immunocompetence in bees (61), ants (62), and moths (63). While studies that investigate individual pathways or enzymes are useful, they may be missing subtle and important changes in the overall metabolism of an organism. By using untargeted metabolomics, we can now examine many metabolic compounds and pathways simultaneously (64) and can attempt to broadly cover the metabolism of toxicants in bees. Metabolomics analyses have been used to characterize bees’ metabolism of the insecticidal compounds thiacloprid (65) and nicotine (66) but not bees’ metabolism of metals or metalloids, so we used untargeted metabolomics to investigate the metabolites that bees produce in response to selenate and cadmium exposure.

Here, we investigated the interactions between the honey bee and its symbiotic microbiome and exposure to selenate and cadmium. We asked three questions. First, is the bee microbiome affected by exposure to selenate or cadmium, and does the microbial response vary over time? Second, what is the bioaccumulation potential of bee-associated bacteria grown in media spiked with selenate or cadmium? Third, what are the metabolic effects of selenate and cadmium exposure as measured through untargeted liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) metabolomics?

(This research was conducted by J. Rothman in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. degree from the University of California, Riverside [UC Riverside] [67].)

RESULTS

Alpha diversity of the honey bee gut microbiome under conditions of exposure to selenate or cadmium.

We obtained 6,879,949 quality-filtered 16S rRNA gene reads that clustered into 126 exact sequence variants (ESVs) across 263 samples, with an average of 26,160 reads per sample (see File SF1 in the supplemental material for the full ESV table). Through rarefaction analyses (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), we determined that our data had acceptable diversity and coverage at a sequencing depth of 10,340 reads per sample, which left us with 249 samples which we used for diversity analyses. We found that neither treatment exposure nor sampling time point significantly affected alpha diversity as measured by Shannon’s diversity index (P = 0.22 or P = 0.06, respectively) or Faith’s phylogenetic diversity (P = 0.82 or P = 0.15, respectively).

Beta diversity of the honey bee gut microbiome under conditions of exposure to selenate or cadmium.

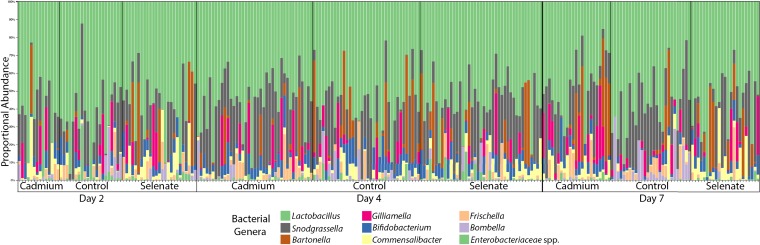

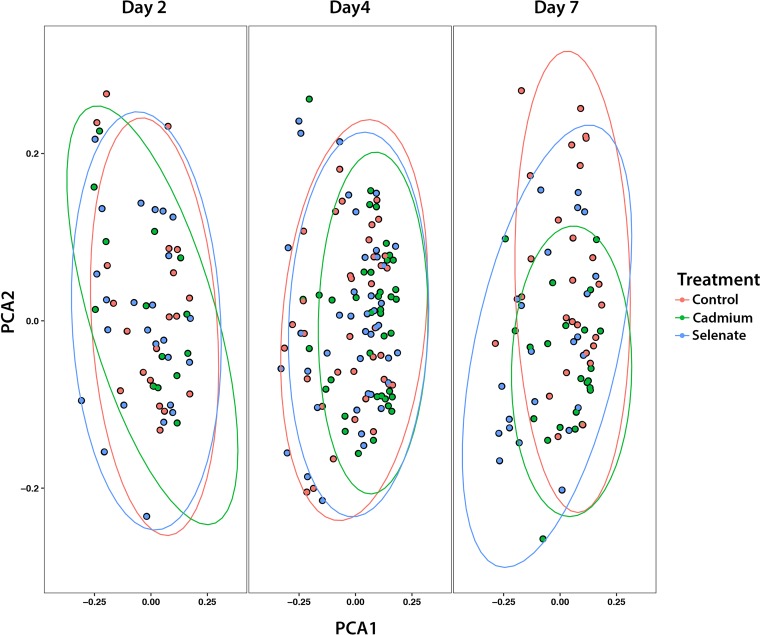

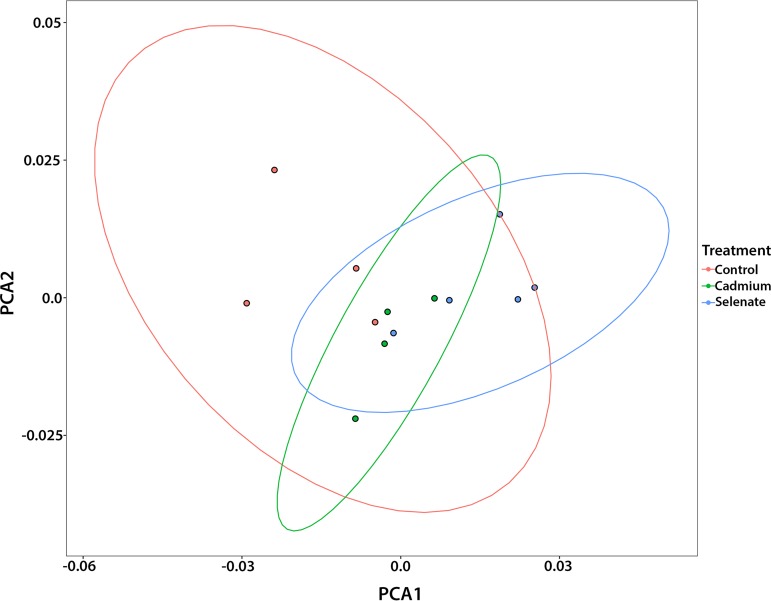

Across all of our samples, we found the following genera of bacteria present at greater than 1% proportional abundance of 16S rRNA gene reads: Lactobacillus, Snodgrassella, Bartonella, Gilliamella, Bifidobacterium, Commensalibacter, Frischella, and Bombella (Fig. 1). We analyzed the beta diversity of our samples through Adonis testing (permutational multivariate analysis of variance [PERMANOVA] with 999 permutations) of the generalized UniFrac distances and found that, overall, treatment (F = 2.96, R2 = 0.02, P = 0.004), sampling time point (F = 2.11, R2 = 0.02, P = 0.017), and the interaction between treatment and time point (F = 1.68, R2 = 0.02, P = 0.023) significantly affected the microbiome of our samples, although our principal-component-analysis (PCA) ordinations did not show any obvious clustering by these terms (Fig. 2). As we had two toxicant treatments, we also analyzed the generalized UniFrac distances for comparisons of each treatment versus controls. We found that under conditions of cadmium exposure, treatment (F = 2.39, R2 = 0.02, P = 0.036), time point (F = 2.19, R2 = 0.03, P = 0.016), and the interaction between treatment and time point (F = 2.33, R2 = 0.03, P = 0.01) all significantly affected the bee microbiome. Similarly, we analyzed the beta diversity of our selenate-exposed samples and found that treatment (F = 3.13, R2 = 0.02, P = 0.005) and the interaction between treatment and time point (F = 1.78, R2 = 0.02, P = 0.044) significantly altered the bee gut community whereas time point alone did not (F = 1.55, R2 = 0.02, P = 0.105). We note that the effects of treatment and time point on the bees’ gut microbial communities were very subtle. We then proceeded to analyze the differential abundances of individual ESVs to understand the interactions between treatment and microbe more thoroughly.

FIG 1.

Stacked bar plot showing bacterial genera present at greater than 1% proportional abundance in each sample. Treatment and sampling time point data are separated by vertical lines.

FIG 2.

PCA plot of the generalized UniFrac distances of all samples. Overall, treatment (F = 2.96, R2 = 0.02, P = 0.004) and sampling time point (F = 2.11, R2 = 0.02, P = 0.017) and the interaction between treatment and time point (F = 1.68, R2 = 0.02, P = 0.023) significantly affected the bee microbiome. Post hoc testing showed that both selenate treatment and cadmium treatment significantly affected the beta diversity of our samples (Benjamini-Hochberg-corrected Padj values of <0.04 for each). Ellipses denote 95% confidence intervals.

Differential abundances of individual ESVs by treatment and sampling time point.

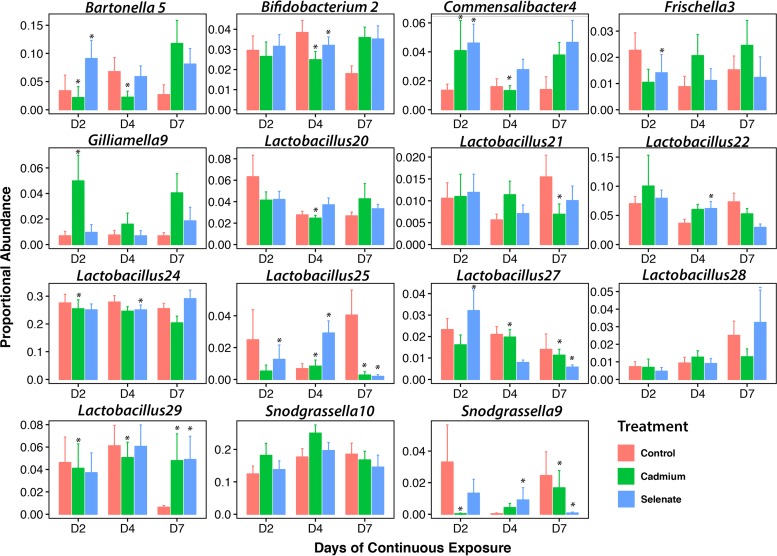

To establish more biologically meaningful effects, we analyzed the differential abundances of individual ESVs present at at least 1% proportional abundance across all samples using DESeq2 software. As we had multiple treatments and multiple sampling time points, we compared ESVs in treatments versus control at each time point and found the following ESVs to be significantly differentially proportional across our analyses (Benjamini-Hochberg-corrected adjusted P [Padj] values of <0.05) (Fig. 3) (for ESV identities and statistics, see Table ST1 in the supplemental material). After 2 days of continuous exposure, we observed an increase of one Commensalibacter ESV (Commensalibacter4) in both treatments; a decrease of one ESV in each of Frischella (Frischella3) and Lactobacillus (Lactobacillus25), and an increase in another ESV of Lactobacillus (Lactobacillus27) and Bartonella (Bartonella5) in selenate treatments; and a decrease of an ESV of Lactobacillus, Snodgrassella, and Bartonella in cadmium treatments (Lactobacillus29, Snodgrassella9, and Bartonella5, respectively). After 4 days continuous exposure, we saw a decrease in an ESV of Bifidobacterium (Bifidobacterium2) and Lactobacillus (Lactobacillus24) but an increase in another Lactobacillus ESV (Lactobacillus25) in both treatments; an increase in an ESV of Lactobacillus (Lactobacillus22) and Snodgrassella (Snodgrassella9) in selenate treatments; and a decrease in an ESV of Bartonella (Bartonella5) and Commensalibacter (Commensalibacter4) and in three ESVs of Lactobacillus (Lactobacillus20, Lactobacillus27, and Lactobacillus29) and an increase in an ESV of Gilliamella in cadmium treatments. Our last sampling time point was 7 days of continuous exposure, where we saw a decrease of two Lactobacillus ESVs (Lactobacillus25 and Lactobacillus27) and one Snodgrassella ESV (Snodgrassella9) and an increase in another Lactobacillus ESV (Lactobacillus29) in both treatments and a decrease in a Lactobacillus ESV (Lactobacillus21) in cadmium treatments only. While we are unable to assign true “strain-level” classifications to our bacterial ESVs with the fragment of the 16S rRNA gene that we sequenced, BLAST search results suggest that Lactobacillus20 is likely from the Firm-4 clade of lactobacilli, Lactobacillus21, Lactobacillus22, Lactobacillus24, Lactobacillus25, and Lactobacillus29 are likely members of the Firm-5 clade, and Lactobacillus27 is likely L. kunkeei.

FIG 3.

Proportional abundances of individual exact sequence variants (ESVs) that were significantly different between at least one treatment and one control as analyzed by DESeq2, separated by time point (D, day). Asterisks (*) denote significant differences between treatment and control (Benjamini-Hochberg-corrected Padj, <0.05), and error bars denote standard errors.

The responses of individual ESVs to treatments varied throughout the experiment. For example, several ESVs of Lactobacillus Firm-5 were affected by the treatments; Lactobacillus25 was negatively impacted by both toxicants, while Lactobacillus29 grew to a much higher proportional abundance after 7 days of exposure. Other ESVs showed interesting trends. After 2 days of continuous exposure to cadmium, an ESV of Bartonella apis showed a slight decrease in proportional abundance, while selenate caused a large upshift in abundance, these proportions then generally leveled off for the remainder of the experiment. Similarly, an ESV of Commensalibacter showed a pattern of increased proportional abundance after 2 days of exposure to both treatments and then leveled off again. Finally, an ESV of Snodgrassella alvi (Snodgrassella9) was generally found at lower proportional abundance in treatments compared to controls.

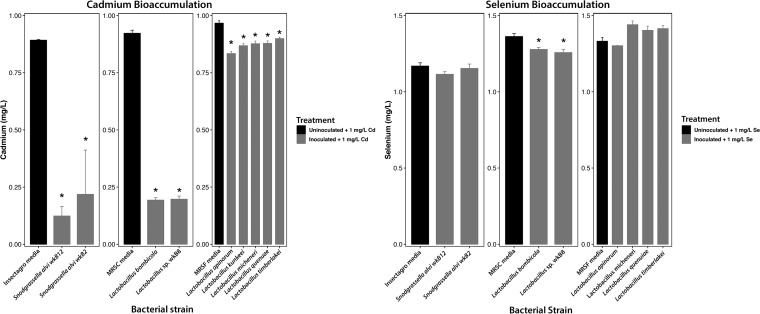

Bacterial removal of selenate or cadmium.

As our bacteria grew in three separate types of media, we separately analyzed the abilities of our bacterial strains to remove selenium and cadmium from their respective media. We found that, overall, the S. alvi strains significantly removed cadmium from their media [F(2,4) = 18.16, P = 0.01], and post hoc testing indicated that both strains did so in a statistically significant manner (wkB12 Padj = 0.010; wkB2 Padj = 0.022). Neither S. alvi strain removed selenium [F(2,5) = 1.35, P = 0.34, Tukey’s honestly significant difference [HSD] test Padj > 0.05]. Next, we found that both Lactobacillus bombicola and wkB8 removed cadmium [F(2,5) = 9.58, P < 0.001, Tukey’s HSD Padj < 0.001 for each] and selenium [F(2,5) = 8.25, P = 0.026, Tukey’s HSD Padj = 0.05 and 0.02, respectively]. We also found that each strain grown in MRS–2% fructose (MRSF) broth (L. micheneri, L. timberlakei, L. quenuiae, L. kunkeei, and L. apinorum) removed cadmium from its medium in a statistically significant manner [F(5,11) = 17.15, P < 0.001], with Tukey’s HSD testing indicating that each strain removed cadmium (Padj < 0.009 for all strains). Finally, while the overall model showed statistical significance, none of the MRSF-grown strains removed selenium from their media in a statistically significant manner [F(4,8) = 5.57, P = 0.02, Tukey’s HSD Padj > 0.05 for all post hoc analyses] (Fig. 4). We also analyzed each medium without bacterial inoculation or toxicant addition in duplicate to account for toxicants inherent in the media and found that no media contained measurable levels of cadmium, while each medium contained selenium (Insectagro, 0.142 mg/liter; MRS–0.25% cysteine [MRSC], 0.260 mg/liter; MRSF, 0.308 mg/liter), albeit at levels lower than those seen in our assay.

FIG 4.

Bar plot showing the amount of cadmium or selenium (in milligrams/liter) present in either bacterium-inoculated media (gray bars) or uninoculated media (black bars) after 2 days of incubation separated by bacterial strain. Asterisks (*) denote significant differences as analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests (Benjamini-Hochberg [BH]-corrected adjusted P value [Padj] < 0.05), and error bars denote standard errors.

Overall metabolite diversity and effect of treatment.

We compared the metabolomic profiles of our whole-abdomen (including the gut) samples through univariate and multivariate statistical analyses. We generated Jaccard distance matrices for the metabolites identified from our LC-MS analyses to assess the overall differences in composition. We then used Adonis software to analyze our results for statistical significance and generated a PCA ordination to visualize the effects of treatments on our samples. Overall, exposure to cadmium and selenate significantly altered the honey bee metabolome (Cd, F = 2.14, R2 = 0.26, P = 0.047; Se, F = 5.23, R2 = 0.43, P = 0.013). Likewise, we saw obvious no clustering by treatment for either cadmium or selenate treatment in the honey bee metabolome (Fig. 5). We note that our data were not heterogeneously dispersed, as indicated through Levene’s test (F = 0.48, P = 0.63).

FIG 5.

PCA plot of the Jaccard distances of individual bee metabolomes in treatments versus control. Exposure to cadmium and selenate significantly altered the honey bee metabolome (for Cd, F = 2.14, R2 = 0.26, P = 0.047; for Se, F = 5.23, R2 = 0.43, P = 0.013). Ellipses denote 95% confidence intervals.

Differential abundances of individual metabolites and biochemical pathways.

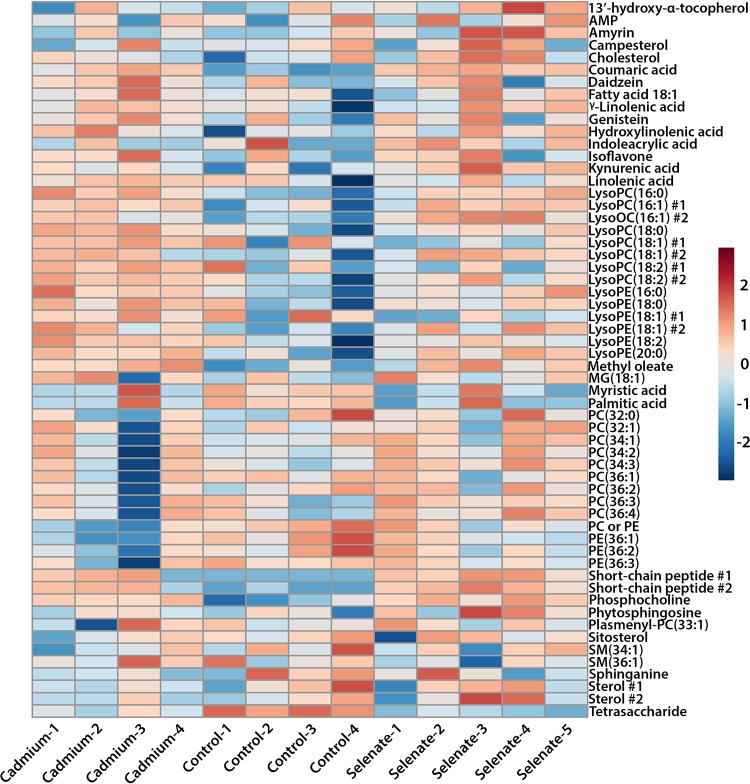

We performed two-tailed Welch’s t tests on log2-transformed individual metabolites identified in our samples in comparisons between treatments to assess statistical significance and corrected for multiple comparisons with a Benjamini-Hochberg-corrected adjusted P value (Padj). We then generated a heat map to visualize the fold change and variability of the metabolites (Fig. 6) and performed metabolite set enrichment analyses (MSEA) to assay the effects that treatment might have had on the bees’ metabolic pathways (Fig. S2). We obtained a profile of 391 metabolites, among which we positively identified 58 (see File SF2 in the supplemental material for the full metabolite list). Examining honey bees treated with cadmium versus controls, we found two metabolites that significantly differed between treatment and control (Padj < 0.05), namely, a coumaric acid-like molecule and a tetrasaccharide (Table 1). MSEA indicated that the phospholipid biosynthesis pathway was significantly different (Padj = 0.004). Next, we examined the effects of selenate exposure on honey bees and found that seven metabolites were significantly different between the selenate and control treatments (Padj < 0.05), namely, a coumaric acid-like molecule, a tetrasaccharide, two short-chain peptides, a lysophosphatidylcholine [LysoPC(16:0)], a LysoPC(16:1), and phosphocholine (Table 1). Again, MSEA showed that phospholipid biosynthesis was impacted by treatment (Padj = 0.01).

FIG 6.

Heat map of bee metabolomes separated by individual sample and metabolite for identified metabolites in control-, selenate-, and cadmium-treated bees. Heat color corresponds to the autoscaled Euclidean distance between samples. LysoPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LysoPE, lysophosphatidylethanolamine; MG, monoacylglycerol; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; SM, sphingomyelin. Number signs (#) denote similarly identified compounds that had distinct m/z values.

TABLE 1.

Significantly different metabolites in treatments versus controls and their m/z, BH-corrected Padj, and fold change valuesa

| Treatment | Metabolite | Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m/z | t test Padj | Fold change | ||

| Cadmium/control | Coumaric acid-like | 165.0547 | 0.03 | +1.31 |

| Tetrasaccharide | 689.2115 | 0.03 | −1.36 | |

| Selenate/control | Coumaric acid-like | 165.0547 | <0.001 | +1.34 |

| Tetrasaccharide | 689.2115 | <0.001 | −1.58 | |

| Short-chain peptide | 273.2172 | <0.001 | +3.13 | |

| Short-chain peptide | 296.1968 | 0.003 | +2.78 | |

| LysoPC(16:1) | 494.3242 | 0.03 | +1.11 | |

| Phosphocholine | 184.0733 | 0.04 | +1.28 | |

| LysoPC(16:0) | 496.3398 | 0.04 | +1.11 | |

Benjamini-Hochberg (BH)-corrected adjusted P values (Padj values) of <0.05 represent significantly different results. LysoPC, lysophosphatidylcholine.

Genes involved in cadmium or selenate resistance/transport.

We annotated the publicly available genomes of bee-associated bacteria (n = 18 genomes, using type strains when possible) that corresponded to taxa observed in our amplicon sequencing study or selenium/cadmium accumulation experiment performed with the RAST server (Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology server) and found that some or all of the following genes were present in each genome: genes encoding selenium ion transporters DedA (68) and TsgA (69) and putative selenium ion and sulfate importer CysA (70); genes encoding components of selenocysteine metabolism, including SelA, SelB, and SelD (71); genes encoding CzcABC, which are components of a cation transporter involved in cadmium resistance (72); the gene encoding cadmium response regulator CzcD (73), and a gene encoding the cadmium-responsive transcriptional regulator CadR (74).

Each strain of bacteria analyzed had the genes corresponding to cadmium resistance gene products CadR and CzcD, although only Commensalibacter intestini had a complete CzcABC protein complex and, presumably, higher cadmium tolerance. Likewise, each bacterial strain except B. apis also had one or more of the putative sulfate/selenium ion transporters TsgA, DedA, and CysA, which may confer selenate resistance, while only B. apis and L. mellifer had genes (encoding SelA, SelB, and SelD) corresponding to selenocysteine metabolism (Fig. S3).

DISCUSSION

Exposure to cadmium or selenate impacted both the microbiomes and metabolomes of honey bees. Cadmium or selenate treatments subtly changed the composition of the honey bee microbiome and changed the proportional abundances of several ESVs of core symbiotic bacterial phylotypes (ESVs with ≥97% sequence identity to previously defined honey bee core phylotypes [20]) based on our 16S rRNA gene sequences. Overall, these subtle changes suggest that the honey bee microbiota is mostly resilient with respect to metal and metalloid exposure, but further research is necessary to determine whether these subtle effects affect host health. Our toxicant removal assays, however, showed that bee-associated bacteria can take up cadmium but (generally) not selenate, possibly protecting the host against heavy metals but not metalloid exposure. Sublethal toxicant exposure led to changes in the bee metabolome, including upregulation of a coumaric acid-like metabolite. p-Coumaric acid is known to upregulate detoxification genes in honey bees (75), suggesting that detoxification pathways may be stimulated by toxicant exposure. Together, these data suggest that metal and metalloid toxicants cause slight perturbations to the honey bee gut microbiome but that the microbiome’s resiliency, the capability of the microbes to remove toxicants, and metabolic responses may help the host deal with these insults.

Previous studies have examined the effects of cadmium on the microbes associated with mice (76) and spiders (44) and the effects of selenate on bumble bee microbes (35). Host-associated microbes can detoxify or sequester toxic metals, including arsenic (47), selenate (35), lead and chromium (48), copper (49), and cadmium (50–52). Our research extends this work by showing that bee-associated microbes can be affected by metal(loid) exposure and are able to bioaccumulate some of these compounds and that the metabolome is changed in response to selenate and cadmium poisoning.

Overall, treatment with either selenate or cadmium slightly altered the honey bee microbiome over the course of our experiment. While the community-wide effects of treatments were subtle and suggested that, overall, the microbiome is mostly resilient to metal or metalloid challenge, there were shifts in the proportional abundance of specific ESVs. Changes in the relative abundance of specific ESVs suggest that exposure to cadmium and selenate may affect symbiont growth in vivo, which could lead to gut dysbiosis and allow disease to proliferate in stressed bees (30, 32). Further work determining whether metal and metalloid challenge leads to dysbiosis or whether these subtle changes indicate resiliency is needed, especially by challenging bees with multiple stressors. While our results suggest that individual ESVs can be affected by metal or metalloid exposure, our data are proportional (77) and we may be observing differential growth in the overall microbiome instead of reduction in individual ESVs or vice versa. Likewise, we recognize that regardless of treatment, the proportional abundances of several ESVs changed over time, which may confound our results. Similar research has been conducted in earthworms showing that cadmium exposure alters the proportional abundance of several ESVs (43), and in mice, where cadmium moderately affects the microbiome (39). Our results also agree with previous experiments that indicated that selenium ion exposure slightly alters the microbiomes of bumble bees (35) and mice (46), suggesting that toxicant exposure may subtly change the microbiome of diverse hosts.

As mentioned above, the proportional abundances of several ESVs were changed by treatment whereas others were apparently unaffected. We used RAST annotations of publicly available honey bee gut bacterial genomes to search for putative mechanisms for toxicant tolerance or sensitivity, although we note that automatic genome annotations do not necessarily correspond to the correct function of each gene. We show that genes corresponding to cadmium resistance and selenium transport are common in the bee gut microbiome, and, as bee symbionts have functionally diverse genomes (78–83), strain-level variation may explain the differences in treatment response between individual ESVs of bacteria corresponding to the same phylotype. Furthermore, putative toxicant resistance genes may not predict symbiont response to toxicants in the dynamic environment of the bee gut, within which diverse host/microbe interactions occur (84). In the case of the bees’ responses to toxicant exposure, immune function may be hampered, which could allow suboptimal population control of gut-associated bacteria (28), leading to the microbiome being in a state of flux. Finally, as we were sampling at distinct time points, we are likely seeing only a snapshot of the bee microbiome and shotgun metagenomic studies may be needed to truly understand community-wide responses to toxicant exposure.

As many of the honey bee gut microbes were resilient to metal or metalloid challenge, we next determined whether common bee-associated bacteria can remove these toxicants from their immediate environment. The potential for bacteria to protect their host from toxic metal exposure through bioaccumulation is an emerging topic of investigation in several systems, including humans (51, 85), mice (49, 52), and insects (48). We exposed strains of bee-associated bacteria to cadmium in vitro and found that all assayed taxa removed a significant amount of cadmium from their growth media after 2 days of incubation. The strains that removed the most cadmium were enteric bacteria isolated from social bees (Lactobacillus sp. wkB8, L. bombicola, and both strains of S. alvi) (86), which indicates that these taxa may remove metal from the host gut. We also found that bacteria associated with solitary bees (L. micheneri, L. quenuiae, and L. timberlakei) (87) and the honey bee crop (L. apinorum and L. kunkeei) (88, 89) removed less cadmium than enteric symbionts but may still provide some protection to host bees. As our sample sizes were small, we recognize that more strains of bacteria are needed to test the hypothesis that enteric bacteria accumulate more cadmium than nonenteric strains. We exposed the same bacteria to selenate in vitro and found that only Firm-5 lactobacilli (Lactobacillus sp. wkB8 and L. bombicola) removed a small but significant amount of the metalloid from their media. These data suggest that the gut microbiome may protect honey bees from cadmium by removing it from the gut, although this needs to be tested in vivo. In our previous research we found that the presence of a normal gut microbiome increases survival of bumble bees challenged with selenate (35), but our results obtained with closely related honey bee microbes suggest that this phenotype may not be the result of direct removal of selenate from the bumble bee gut. Further in vivo experiments are needed to test possible mechanisms. Likewise, we did not measure the overall growth of the bacteria, so toxicant accumulation differences may have been due to varied bacterial density in culture, although we note that visually obvious pellets formed in the media.

Besides removal of toxicants from the gut, the host and microbiota may respond to toxicant challenge by upregulating metabolites involved in detoxification. We used untargeted LC-MS analyses to assay the metabolites present in cadmium-treated or selenate-treated bees compared to controls and found that both treatments altered the overall metabolome of the bees along with several individual metabolites. Two metabolites were differentially abundant in the two treatments: a tetrasaccharide (lower abundance in treatments) and a coumaric acid-like molecule (higher abundance in treatments). As tetrasaccharides are common storage carbohydrates in plants (90) and as we fed a soy-based pollen substitute to the bees, the reduction of tetrasaccharide levels in toxicant-exposed bees may have been due to treatments causing bees to decrease diet consumption. While honey bees are not known to be able to detect cadmium or selenate in their diet (55, 91), the chronic effects of sublethal toxicant exposure on the gustatory response of honey bees are unknown and should be assayed in future experiments. Coumaric acid is involved in upregulating detoxification genes in honey bees (75), but its metabolites are unknown, so the “coumaric acid-like” compound that we detected may be part of the bees’ metabolism or may have come directly from their diet. Regardless of its source, as coumaric acid is important in honey bee detoxification, future experiments determining its role in metal and metalloid tolerance and whether the microbiome has a role in production of the coumaric acid-like metabolite are needed. We also observed an increase in the abundance of short-chain peptides in selenate-exposed bees, which probably indicates that protein degradation occurred as a response to treatment (92), as selenium ions have been shown to increase protein degradation in cell models (93, 94). Finally, we saw higher proportional abundances of the phospholipid precursor phosphocholine (95) and of two lysophosphatidylcholines—products of oxidized phospholipids (96)—in selenate treatments as well as MSEA results that indicated overexpression of phospholipid biosynthesis metabolites in both treatments. We posit that the higher proportional abundances of these phospholipid metabolites may have been due to the oxidative stress that toxic doses of metals or metalloids can produce, as has been shown previously in yeast (97) and in honey bees (98). While our metabolomic results yield insights, we note that our small sample size may have prevented us from finding more finely scaled changes to individual metabolites. Previous work has shown that the bumble bee microbiome reduces mortality upon selenate challenge (35), and as the bee microbiome is involved in suppressing oxidative damage (29, 31), antioxidant activity may explain the mechanism of microbially mediated protection against toxicants. We suggest future research that will investigate the ability of antioxidants to remedy the effects of toxicant exposure on insects.

Conclusion.

Bees are important insect pollinators that are excellent for studying host/microbe interactions and the toxicology of chemical compounds. Our interdisciplinary study indicated that the honey bee microbiome is mostly resilient with respect to cadmium and selenate exposure but that there are potentially susceptible strains of core symbionts. We also show that several bee-associated strains of bacteria can bioaccumulate cadmium—and, to a lesser degree, selenate—which may provide a protective mechanism for bees against metal and metalloid pollution and provide genes putatively involved in detoxification to these chemicals. Finally, we report metabolic responses by honey bees upon toxicant exposure and posit that these toxicants may cause oxidative damage to proteins and lipids while also possibly upregulating detoxification genes, although much more investigation into the bee metabolome is needed. We suggest that future research investigate the interactions of toxicants and subcellular through organismal responses of both symbionts and honey bees to understand the complex interplay within this system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bee care and cage rearing.

We removed one frame of brood each from five healthy honey bee colonies with marked Italian queens and housed them in a hive body at 35°C and 50% humidity under conditions of constant darkness. We then allowed the bees to emerge, mixed the newly emerged workers (NEWs) to randomize their colony of origin, and placed 50 NEWs each into 39 separate 13-cm-by-10.5-cm-by-6.5-cm wire cages equipped with two feeders, one containing 35 ml of deionized water and one with 35 ml 50% sucrose. We also provided an artificial pollen patty to each cage of bees consisting of 269 g corn syrup, 113 g sucrose, and 113 g Bee Pro (Mann Lake, Hackensack, MN). To inoculate the newly emerged workers with their “core” microbiome, we collected 50 ml of foragers from the source hives of the NEWs, immobilized the bees at 4°C, aseptically dissected the abdomens, and macerated the whole abdomens in 50% sucrose. We added 1 ml of the resulting slurry to 34 ml of 50% sucrose solution and fed it to the NEWs. We allowed the bees to feed ad libitum on the macerated abdomen/sucrose mixture for 2 days before replacing the feeders with 50% sucrose alone. We allowed the bees to feed for 3 more days to fully establish a microbiome (22).

Once the bees had an established microbiome, we prepared treatment feeding solutions of 50% sucrose (as a no-metal/metalloid control), 50% sucrose spiked with 0.6 mg/liter sodium selenate or 50% sucrose with 0.24 mg/liter cadmium chloride (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA), and pollen patties spiked with either 6.0 mg/liter selenium or 0.46 mg/liter cadmium as described previously by Hladun et al. (5). Using a random-number generator, we randomly assigned treatments (13 each control, cadmium, and selenate) to each cage and again allowed the bees to feed ad libitum. We sampled three bees from each cage after 2, 4, and 7 days of exposure and immediately placed the samples on dry ice, followed by long-term storage at –80°C.

DNA extractions and 16S rRNA gene sequencing library preparation.

We used a DNA extraction protocol described previously by Engel et al. (99), Pennington et al. (100), and Rothman et al. (101). We subjected whole-bee samples to gentle vortex mixing in 0.1% sodium hypochlorite followed by three rinses with ultrapure water for surface sterilization. We then used sterile forceps to dissect the whole gut from each bee and transferred the gut into DNeasy blood and tissue kit lysis plates (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) containing approximately 100 μl of 0.1-mm-diameter glass beads, one 3.4-mm-diameter steel-chrome bead (Biospec, Bartlesville, OK), and 180 μl of buffer ATL. We then homogenized the guts with a Qiagen TissueLyser at 30 Hz for 6 min. We followed the remainder of the Qiagen blood and Tissue protocol after homogenization. To control for reagent contamination, we also included blanks which we extracted, prepared, and sequenced in the same fashion as the samples.

We prepared 16S rRNA gene libraries for paired-end Illumina MiSeq sequencing using the protocol previously described by McFrederick and Rehan (102), Pennington et al. 2017 (103) and Rothman et al. (104). We incorporated the 16S rRNA gene primer sequence, unique barcode sequence, and Illumina adapter sequence as described previously (105). We used the primers 799F-mod3 (106) and 1115R (105) to amplify the V5-V6 region of the 16S rRNA gene under PCR conditions that included the use of 4 μl of template DNA, 0.5 μl of 10 μM 799F-mod3, 0.5 μl of 10 μM 1115R, 10 μl PCR-grade water, and 10 μl Pfusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and an annealing temperature of 52°C and subjected the reaction mixture to 30 cycles in a C1000 Touch thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). We then removed excess primers and deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) with a PureLink Pro 96 PCR purification kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). We used the cleaned PCR products as the template for a second PCR using 1 μl of the cleaned PCR amplicons as a template with primers PCR2F and PCR2R to complete the Illumina adapter sequence (105). We performed PCR using 0.5 μl of 10 μM forward primer, 0.5 μl of 10 μM reverse primer, 1 μl of template, 13 μl of ultrapure water, and 10 μl of Pfusion DNA polymerase at an annealing temperature of 58°C for 15 cycles. We normalized the resulting libraries with a SequalPrep normalization kit following the supplied protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). We pooled 5-μl volumes from all of the normalized libraries and performed a final cleanup step with a single-column PureLink PCR purification kit. Finally, we checked the normalized amplicons on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) and sequenced the multiplexed libraries using a V3 reagent kit at 2 × 300 cycles on an Illumina MiSeq sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA) at the Genomics Core Facility of UC Riverside.

Bioinformatics and statistics.

We used QIME2-2019.1 (107) to process the 16S rRNA gene sequence libraries. We first visualized and trimmed the low-quality ends of the reads with QIIME2 and then used DADA2 (108) to assign our sequences to exact sequence variants (ESVs; 16S rRNA gene sequences that are 100% matches), remove chimeras, and remove reads with more than two expected errors. We assigned taxonomy to the ESVs using the q2-feature-classifer (109) trained to the 799-to-1,115 region of the 16S rRNA gene with the SILVA database (110). We also conducted local BLASTn searches against the NCBI 16S microbial database and nt/nr (accessed April 2019). We filtered out features from the resulting ESV table that corresponded to contaminants as identified in our blanks (111) or that were present at only one read (singletons). We used the MAFFT aligner (112) and FastTree v2.1.3 to generate a phylogenetic tree of our sequences (113). We used the resulting tree and ESV table to analyze alpha diversity and to tabulate a generalized UniFrac distance matrix (114) for beta diversity comparisons. We visualized the UniFrac distances through two-dimensional principal-component analysis (PCA) with the R package ggplot2 (115). We analyzed the alpha diversity of our samples by the use of Shannon’s diversity index and Faith’s phylogenetic diversity using the Kruskal-Wallis test in QIIME2. We tested our beta diversity data for statistical significance in R v3.5.1 (116) with the packages vegan (117) and DESeq2 (118).

Bacterial accumulation of cadmium or selenate.

In order to assay the ability of bee-associated bacterial species to remove cadmium or selenate from their environment, we streaked out individual colonies of strains wkB2 and wkB12 of Snodgrassella alvi on plates containing tryptic soy agar (Neogen, Lansing, MI) plus 5% defibrinated sheep blood (Hemostat Labs, Dixon, CA) (TSAB) in a 5% CO2 environment; Lactobacillus bombicola and the Lactobacillus Firm-5 strain wkB8 on De Man Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS)–0.05% cysteine agar (MRSC; Research Products Inc., Mt. Prospect, IL); and L. micheneri, L. timberlakei, L. quenuiae, L. kunkeei strain 3L, and L. apinorum in MRS–2% fructose agar (MRSF; Research Products Inc., Mt. Prospect, IL). We then transferred individual colonies of the S. alvi strains into 15 ml of Insectagro media (Corning Inc., Corning, NY); L. bombicola and Lactobacillus sp. wkB8 into 15 ml of MRSC media; and L. micheneri, L. timberlakei, L. quenuiae, L. kunkeei, and L. apinorum into 15 ml of MRSF media spiked with either 1 mg/liter sodium selenate or 1 mg/liter cadmium chloride (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA). We incubated the S. alvi cultures at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere without shaking and the Lactobacillus spp. at 32°C with shaking at 150 rpm for 2 days. While the strains likely grew to different densities, we measured their ability to remove toxicants independently of their final density. All assays were conducted in triplicate, and we also included sterile medium samples with or without spiking of 1 mg/liter of each treatment as controls.

After incubation was performed, we pelleted the bacterial samples via centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 10 min, followed by three washes with 18-MΩ ultrapure water and subsequent centrifugations. We then transferred the supernatant and washed volumes to 110-ml Teflon-lined vessels and added 5 ml of TraceMetal-grade concentrated HNO3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) followed by digestion in a 570-W microwave oven (CEM Corp., Matthews, NC) for 20 min. Finally, we diluted the samples with TraceMetal-grade HCl (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) (6 M), heated them for 20 min at 90°C, and filtered the samples through a 0.45-μm-pore-size syringe filter as previously described by Hladun et al. (5). We then analyzed the selenium and cadmium concentrations of the media via inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) performed with a Perkin-Elmer Optima 7300DV spectrometer in the Environmental Sciences Research Laboratory at UC Riverside and tested for differences in our bacterial accumulation data by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s HSD test for post hoc comparisons.

Sample preparation for untargeted metabolomics.

We sampled three bees from 13 cages after 4 days of continuous exposure of the bees to the treatments described above and immediately placed the samples on dry ice, followed by long-term storage at –80°C. We then pooled three bee abdomens from each cage, freeze-dried the samples, and homogenized the abdomens to a fine powder at 4°C using a bead mill homogenizer. Next, we extracted 10 to 12 mg of the powder in a 1.5-ml tube with 100 μl of ice-cold extraction solvent (30:30:20:20 acetonitrile-methanol-water-isopropanol) per milligram of tissue. We sonicated the samples for 5 min in an ice bath and then subjected them to vortex mixing for 30 min at 4°C. Finally, we centrifuged the samples at 16,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and analyzed the supernatant with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

Untargeted LC-MS metabolomics.

We used a Synapt G2-Si quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA) coupled to an I-class ultraperformance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system (Waters) for LC-MS analyses in the UC Riverside Metabolomics Core Facility. We carried out separations on a CSH phenyl-hexyl column (Waters, Milford, MA) (2.1 by 100 mm, 1.7 μM pore size) at a flow rate of 250 μl/min at 40°C with the following mobile phases: phase A, water–0.1% formic acid; phase B, acetonitrile–0.1% formic acid. We injected 2 μl of sample extract, and the gradient steps were as follows: 0 min, 1% phase B; 1 min, 1% phase B; 8 min, 40% phase B; 24 min, 100% phase B; 26.5 min, 100% phase B; 27 min, 1% phase B. We operated the MS instrument in positive-ion mode (50 to 1,200 m/z) with 100 ms of scan time and acquired tandem MS (MS/MS) data at 1 MS/MS scan per MS scan. We set the source and desolvation temperatures to 150°C and 600°C, respectively. We set the desolvation gas flow rate to 1,100 liters/h and the cone gas flow rate to 150 liters/h, with all gases being nitrogen except the collision gas, which was argon, and set the capillary voltage to 1 kV. We generated a quality control sample by pooling equal aliquots of all samples and analyzed the pool every 3 to 4 injections to monitor system stability and performance. We analyzed samples in random order and used leucine enkephalin infusion for mass correction.

Metabolomics data processing.

We processed the metabolite data (peak picking, alignment, deconvolution, integration, normalization, and spectral matching) with Progenesis Qi software (Nonlinear Dynamics, Durham, NC). We normalized the resulting data to the total ion abundance and removed features with a coefficient of variation greater than 20% or an average abundance less than 200 in the quality control injections as described previously (119, 120). To aid in the identification of features belonging to the same metabolite, we assigned features a cluster identifier (ID) using RAMClust (121). Next, we used a slightly modified version of the metabolomics standard initiative guidelines to assign annotation level confidence (122, 123): Annotation level 1 indicates a match of MS and MS/MS or of MS and retention time to an in-house database generated with authentic standards. Level 2a indicates a match of MS and MS/MS to an external database. Level 2b indicates a match of MS and MS/MS to the LipidBlast database (124) or a match of MS and diagnostic evidence (i.e., the dominant presence of an m/z 85 fragment ion for acylcarnitines). We searched against several mass spectral metabolite databases, including Metlin, Massbank of North America (124, 125), and an in-house database in the UC Riverside Metabolomics Core Facility. After metabolites were identified and quantified, we used MetaboAnalyst v4.0 (126) for data handling, log2 normalization, statistical testing through Welch’s t test (identified metabolites only), quantitative metabolite pathway enrichment analysis (using MSEA), and heat map plotting. Additionally, we built Jaccard distance matrices and tested our treatments for statistical significance through Adonis testing (PERMANOVA with 999 permutations) and Levene’s test in the vegan R package (117) and plotted PCA ordinations with the R package ggplot2.

Genomic annotations and metal/metalloid detoxification genes.

We downloaded publicly accessible genome sequences from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) for the following bacterial species: Bartonella apis, Bifidobacterium asteroides, Bombella intestini, Commensalibacter intestini, Frischella perrara, Gilliamella apicola, Lactobacillus apinorum, L. apis, L. bombicola, L. helsingborgensis, L. kullabergensis, L. kunkeei, L. mellifer, L. melliventris, L. micheneri, L. quenuiae, Lactobacillus sp. wkB8 (Firm-5), L. timberlakei, and Snodgrassella alvi (see Table ST2 for accession numbers). We then used the RAST server (Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology server) (127) to annotate the genomes and identify genes from the subsystem categories “Cobalt-zinc-cadmium resistance,” “Uptake of selenate and selenite,” and “Selenocysteine metabolism” to find a genomic basis for toxicant tolerance and uptake.

Data availability.

Raw sequencing data are available on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession number PRJNA543376. Raw metabolome data are available on the NIH Metabolomics Data Repository and Coordinating Center Metabolomics Workbench under study number ST001187 (https://www.metabolomicsworkbench.org/data/DRCCMetadata.php?Mode=Study&StudyID=ST001187&StudyType=MS&ResultType=2).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Genomics Core facility staff of UC Riverside, for their next-generation sequencing expertise; the UC Riverside Metabolomics Core facility staff for their assistance with metabolomics analyses; and the UC Riverside Environmental Sciences Research Laboratory staff for ICP analyses. We also thank Kaleigh Russell and Hoang Vuong for assistance with bee collection and Nancy Moran, Waldan Kwong, and Eli Powel for bacterial strains.

This research was supported by Initial Complement funds, NIFA Hatch funds (CA-R-ENT-5109-H), and an IIGB Metabolomics Seed Grant from UC Riverside to Q.S.M. L.L. was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (ID no. 2019237595). Support was also provided through fellowships awarded to J.A.R. by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration MIRO Fellowships in Extremely Large Data Sets (award no. NNX15AP99A), a United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture Predoctoral Fellowship (award no. 2018-67011-28123), and a Dissertation Research Grant from UC Riverside. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01411-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klein A-M, Vaissière BE, Cane JH, Steffan-Dewenter I, Cunningham SA, Kremen C, Tscharntke T. 2007. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc Biol Sci 274:303–313. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilar R, Ashworth L, Galetto L, Aizen MA. 2006. Plant reproductive susceptibility to habitat fragmentation: review and synthesis through a meta-analysis. Ecol Lett 9:968–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calderone NW. 2012. Insect pollinated crops, insect pollinators and us agriculture: trend analysis of aggregate data for the period 1992–2009. PLoS One 7:e37235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goulson D, Nicholls E, Botias C, Rotheray EL. 2015. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science 347:1255957. doi: 10.1126/science.1255957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hladun KR, Di N, Liu T-X, Trumble JT. 2016. Metal contaminant accumulation in the hive: consequences for whole-colony health and brood production in the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.). Environ Toxicol Chem 35:322–329. doi: 10.1002/etc.3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sovik E, Perry CJ, LaMora A, Barron AB, Ben-Shahar Y. 2015. Negative impact of manganese on honeybee foraging. Biol Lett 11:20140989. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Celli G, Maccagnani B. 2003. Honey bees as bioindicators of environmental pollution. Bull Insectology 56:137–139. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tchounwou PB, Yedjou CG, Patlolla AK, Sutton DJ. 2012. Heavy metal toxicity and the environment, p 133–164. In Luch A. (ed), Molecular, clinical and environmental toxicology. Experientia supplementum, vol 101 Springer, Basel, Switzerland. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7643-8340-4_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmgren GGS, Meyer MW, Chaney RL, Daniels RB. 1993. Cadmium, lead, zinc, copper, and nickel in agricultural soils of the United States of America. J Environ Qual 22:335. doi: 10.2134/jeq1993.00472425002200020015x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vickerman DB, Trumble JT, George GN, Pickering IJ, Nichol H. 2004. Selenium biotransformations in an insect ecosystem: effects of insects on phytoremediation. Environ Sci Technol 38:3581–3586. doi: 10.1021/es049941s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hladun KR, Parker DR, Trumble JT. 2015. Cadmium, copper, and lead accumulation and bioconcentration in the vegetative and reproductive organs of Raphanus sativus: implications for plant performance and pollination. J Chem Ecol 41:386–395. doi: 10.1007/s10886-015-0569-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hladun KR, Parker DR, Tran KD, Trumble JT. 2013. Effects of selenium accumulation on phytotoxicity, herbivory, and pollination ecology in radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Environ Pollut 172:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn CF, Prins CN, Freeman JL, Gross AM, Hantzis LJ, Reynolds RJB, Yang SI, Covey PA, Bañuelos GS, Pickering IJ, Fakra SC, Marcus MA, Arathi HS, Pilon-Smits EAH, Yang S. 2011. Selenium accumulation in flowers and its effects on pollination. New Phytol 192:727–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henson TM, Cory W, Rutter MT. 2013. Extensive variation in cadmium tolerance and accumulation among populations of Chamaecrista fasciculata. PLoS One 8:e63200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conti ME, Botrè F. 2001. Honeybees and their products as potential bioindicators of heavy metals contamination. Environ Monit Assess 69:267–282. doi: 10.1023/A:1010719107006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roman A. 2010. Levels of copper, selenium, lead, and cadmium in forager bees. Polish J Environ Stud 19:663–669. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di N, Hladun KR, Zhang K, Liu TX, Trumble JT. 2016. Laboratory bioassays on the impact of cadmium, copper and lead on the development and survival of honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) larvae and foragers. Chemosphere 152:530–538. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meindl GA, Ashman T-L. 2013. The effects of aluminum and nickel in nectar on the foraging behavior of bumblebees. Environ Pollut 177:78–81. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinson VG, Danforth BN, Minckley RL, Rueppell O, Tingek S, Moran NA. 2011. A simple and distinctive microbiota associated with honey bees and bumble bees. Mol Ecol 20:619–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moran NA, Hansen AK, Powell JE, Sabree ZL. 2012. Distinctive gut microbiota of honey bees assessed using deep sampling from individual worker bees. PLoS One 7:e36393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwong WK, Medina LA, Koch H, Sing K-W, Soh EJY, Ascher JS, Jaffé R, Moran NA. 2017. Dynamic microbiome evolution in social bees. Sci Adv 3:e1600513. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell JE, Martinson VG, Urban-Mead K, Moran NA. 2014. Routes of acquisition of the gut microbiota of the honey bee Apis mellifera. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:7378–7387. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01861-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng H, Nishida A, Kwong WK, Koch H, Engel P, Steele MI, Moran NA. 2016. Metabolism of toxic sugars by strains of the bee gut symbiont Gilliamella apicola. mBio 7:e01326-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01326-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer-Young EC, Raffel TR, McFrederick QS. 2018. Temperature-mediated inhibition of a bumblebee parasite by an intestinal symbiont. Proc R Soc B 285:20182041. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2018.2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarz RS, Moran NA, Evans JD. 2016. Early gut colonizers shape parasite susceptibility and microbiota composition in honey bee workers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:9345–9350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606631113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koch H, Schmid-Hempel P. 2011. Socially transmitted gut microbiota protect bumble bees against an intestinal parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:19288–19292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110474108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raymann K, Coon KL, Shaffer Z, Salisbury S, Moran NA. 2018. Pathogenicity of Serratia marcescens strains in honey bees. mBio 9:e01649-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01649-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwong WK, Mancenido AL, Moran NA. 2017. Immune system stimulation by the native gut microbiota of honey bees. R Soc Open Sci 4:170003. doi: 10.1098/rsos.170003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng H, Powell JE, Steele MI, Dietrich C, Moran NA. 2017. Honeybee gut microbiota promotes host weight gain via bacterial metabolism and hormonal signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:4775–4780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701819114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson KE, Ricigliano VA. 2017. Honey bee gut dysbiosis: a novel context of disease ecology. Curr Opin Insect Sci 22:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maes P, Rodrigues P, Oliver R, Mott BM, Anderson KE. 2016. Diet related gut bacterial dysbiosis correlates with impaired development, increased mortality and Nosema disease in the honey bee Apis mellifera. Mol Ecol 25:5439–5450. doi: 10.1111/mec.13862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raymann K, Shaffer Z, Moran NA. 2017. Antibiotic exposure perturbs the gut microbiota and elevates mortality in honeybees. PLoS Biol 15:e2001861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li JH, Evans JD, Li WF, Zhao YZ, DeGrandi-Hoffman G, Huang SK, Li ZG, Hamilton M, Chen YP. 2017. New evidence showing that the destruction of gut bacteria by antibiotic treatment could increase the honey bee’s vulnerability to Nosema infection. PLoS One 12:e0187505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engel P, Bartlett KD, Moran NA. 2015. The bacterium Frischella perrara causes scab formation in the gut of its honeybee host. mBio 6:e00193-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00193-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothman JA, Leger L, Graystock P, Russell K, McFrederick QS. 26 April 2019, posting date The bumble bee microbiome increases survival of bees exposed to selenate toxicity. Environ Microbiol. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Claus SP, Guillou H, Ellero-Simatos S. 2016. The gut microbiota: a major player in the toxicity of environmental pollutants? NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2:16003. doi: 10.1038/npjbiofilms.2016.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evariste L, Barret M, Mottier A, Mouchet F, Gauthier L, Pinelli E. 2019. Gut microbiota of aquatic organisms: a key endpoint for ecotoxicological studies. Environ Pollut. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVPOL.2019.02.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tinkov AA, Gritsenko VA, Skalnaya MG, Cherkasov SV, Aaseth J, Skalny AV. 2018. Gut as a target for cadmium toxicity. Environ Pollut 235:429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richardson JB, Dancy BCR, Horton CL, Lee YS, Madejczyk MS, Xu ZZ, Ackermann G, Humphrey G, Palacios G, Knight R, Lewis JA. 2018. Exposure to toxic metals triggers unique responses from the rat gut microbiota. Sci Rep 8:6578. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24931-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ba Q, Li M, Chen P, Huang C, Duan X, Lu L, Li J, Chu R, Xie D, Song H, Wu Y, Ying H, Jia X, Wang H. 2017. Gender-dependent effects of cadmium exposure in early life on gut microbiota and fat accumulation in mice. Environ Health Perspect 125:437–446. doi: 10.1289/EHP360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y, Li Y, Liu K, Shen J. 2014. Exposing to cadmium stress cause profound toxic effect on microbiota of the mice intestinal tract. PLoS One 9:e85323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Breton J, Massart S, Vandamme P, De Brandt E, Pot B, Foligné B. 2013. Ecotoxicology inside the gut: impact of heavy metals on the mouse microbiome. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 14:62. doi: 10.1186/2050-6511-14-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Srut M, Menke S, Höckner M, Sommer S. 2019. Earthworms and cadmium—heavy metal resistant gut bacteria as indicators for heavy metal pollution in soils? Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 171:843–853. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.12.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang H, Wang J, Lv Z, Tian J, Peng Y, Peng X, Xu X, Song Q, Lv B, Chen Z, Sun Z, Wang Z. 2018. Metatranscriptome analysis of the intestinal microorganisms in Pardosa pseudoannulata in response to cadmium stress. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 159:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhai Q, Cen S, Li P, Tian F, Zhao J, Zhang H, Chen W. 2018. Effects of dietary selenium supplementation on intestinal barrier and immune responses associated with its modulation of gut microbiota. Environ Sci Technol Lett 5:724–730. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.8b00563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kasaikina MV, Kravtsova MA, Lee BC, Seravalli J, Peterson DA, Walter J, Legge R, Benson AK, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. 2011. Dietary selenium affects host selenoproteome expression by influencing the gut microbiota. FASEB J 25:2492–2499. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-181990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coryell M, McAlpine M, Pinkham NV, McDermott TR, Walk ST. 2018. The gut microbiome is required for full protection against acute arsenic toxicity in mouse models. Nat Commun 9:5424. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07803-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Senderovich Y, Halpern M. 2013. The protective role of endogenous bacterial communities in chironomid egg masses and larvae. ISME J 7:2147–2158. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tian F, Xiao Y, Li X, Zhai Q, Wang G, Zhang Q, Zhang H, Chen W. 2015. Protective effects of Lactobacillus plantarum CCFM8246 against copper toxicity in mice. PLoS One 10:e0143318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumar N, Kumar V, Panwar R, Ram C. 2016. Efficacy of indigenous probiotic Lactobacillus strains to reduce cadmium bioaccessibility—an in vitro digestion model. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7779-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daisley BA, Monachese M, Trinder M, Bisanz JE, Chmiel JA, Burton JP, Reid G. 2019. Immobilization of cadmium and lead by Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 mitigates apical-to-basolateral heavy metal translocation in a Caco-2 model of the intestinal epithelium. Gut Microbes 10:321–333. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1526581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhai Q, Wang G, Zhao J, Liu X, Tian F, Zhang H, Chen W. 2013. Protective effects of Lactobacillus plantarum CCFM8610 against acute cadmium toxicity in mice. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:1508–1515. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03417-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu L, Zhai Q, Liu X, Wang G, Zhang Q, Zhao J, Narbad A, Zhang H, Tian F, Chen W. 2015. Lactobacillus plantarum CCFM639 alleviates aluminium toxicity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-7135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu G, Xiao X, Feng P, Xie F, Yu Z, Yuan W, Liu P, Li X. 2017. Gut remediation: a potential approach to reducing chromium accumulation using Lactobacillus plantarum TW1-1. Sci Rep 7:15000. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15216-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burden CM, Morgan MO, Hladun KR, Amdam GV, Trumble JJ, Smith BH. 2019. Acute sublethal exposure to toxic heavy metals alters honey bee (Apis mellifera) feeding behavior. Sci Rep 9:4253. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40396-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crall JD, Switzer CM, Oppenheimer RL, Ford Versypt AN, Dey B, Brown A, Eyster M, Guérin C, Pierce NE, Combes SA, de Bivort BL. 2018. Neonicotinoid exposure disrupts bumblebee nest behavior, social networks, and thermoregulation. Science 362:683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.aat1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nikolić TV, Kojić D, Orčić S, Vukašinović EL, Blagojević DP, Purać J. 2019. Laboratory bioassays on the response of honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) glutathione S-transferase and acetylcholinesterase to the oral exposure to copper, cadmium, and lead. Environ Sci Pollut Res 26:6890. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3950-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Badiou-Bénéteau A, Benneveau A, Géret F, Delatte H, Becker N, Brunet JL, Reynaud B, Belzunces LP. 2013. Honeybee biomarkers as promising tools to monitor environmental quality. Environ Int 60:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gauthier M, Aras P, Jumarie C, Boily M. 2016. Low dietary levels of Al, Pb and Cd may affect the non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity in caged honey bees (Apis mellifera). Chemosphere 144:848–854. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jumarie C, Aras P, Boily M. 2017. Mixtures of herbicides and metals affect the redox system of honey bees. Chemosphere 168:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Polykretis P, Delfino G, Petrocelli I, Cervo R, Tanteri G, Montori G, Perito B, Branca JJV, Morucci G, Gulisano M. 2016. Evidence of immunocompetence reduction induced by cadmium exposure in honey bees (Apis mellifera). Environ Pollut 218:826–834. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sorvari J, Rantala LM, Rantala MJ, Hakkarainen H, Eeva T. 2007. Heavy metal pollution disturbs immune response in wild ant populations. Environ Pollut 145:324–328. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu G, Yi Y. 2015. Effects of dietary heavy metals on the immune and antioxidant systems of Galleria mellonella larvae. Comp Biochem Physiol Part C Toxicol Pharmacol 167:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patti GJ, Yanes O, Siuzdak G. 2012. Metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13:263–269. doi: 10.1038/nrm3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shi T, Burton S, Wang Y, Xu S, Zhang W, Yu L. 2018. Metabolomic analysis of honey bee, Apis mellifera L. response to thiacloprid. Pestic Biochem Physiol 152:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Du Rand EE, Smit S, Beukes M, Apostolides Z, Pirk CWW, Nicolson SW. 2015. Detoxification mechanisms of honey bees (Apis mellifera) resulting in tolerance of dietary nicotine. Sci Rep 5:11779. doi: 10.1038/srep11779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rothman JA. 2019. Effects of toxicant exposure on honey bee and bumble bee microbiomes and impacts on host health. PhD dissertation. University of California, Riverside, Riverside, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ledgham F, Quest B, Vallaeys T, Mergeay M, Covès J. 2005. A probable link between the DedA protein and resistance to selenite. Res Microbiol 156:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guzzo J, Dubow MS. 2000. A novel selenite- and tellurite-inducible gene in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:4972–4978. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.11.4972-4978.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lindblow-Kull C, Kull FJ, Shrift A. 1985. Single transporter for sulfate, selenate, and selenite in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 163:1267–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Forchhammer K, Bock A. 1991. Selenocysteine synthase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 266:6324–6328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nies DH. 1995. The cobalt, zinc, and cadmium efflux system CzcABC from Alcaligenes eutrophus functions as a cation-proton antiporter in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 177:2707–2712. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2707-2712.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Anton A, Grosse C, Reissmann J, Pribyl T, Nies DH. 1999. CzcD is a heavy metal ion transporter involved in regulation of heavy metal resistance in Ralstonia sp. strain CH34. J Bacteriol 181:6876–6881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brocklehurst K, Megit S, Morby A. 2003. Characterisation of CadR from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a Cd(II)-responsive MerR homologue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 308:234–239. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01366-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mao W, Schuler MA, Berenbaum MR. 2013. Honey constituents up-regulate detoxification and immunity genes in the western honey bee Apis mellifera. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:8842–8846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303884110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhai Q, Li T, Yu L, Xiao Y, Feng S, Wu J, Zhao J, Zhang H, Chen W. 2017. Effects of subchronic oral toxic metal exposure on the intestinal microbiota of mice. Sci Bull 62:831–840. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2017.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gloor GB, Macklaim JM, Pawlowsky-Glahn V, Egozcue JJ. 2017. Microbiome datasets are compositional: and this is not optional. Front Microbiol 8:2224. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ellegaard KM, Engel P. 2019. Genomic diversity landscape of the honey bee gut microbiota. Nat Commun 10:446. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08303-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Engel P, Stepanauskas R, Moran NA. 2014. Hidden diversity in honey bee gut symbionts detected by single-cell genomics. PLoS Genet 10:e1004596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Engel P, Martinson VG, Moran NA. 2012. Functional diversity within the simple gut microbiota of the honey bee. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:11002–11007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202970109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ellegaard KM, Engel P. 2016. Beyond 16S rRNA community profiling: intra-species diversity in the gut microbiota. Front Microbiol 7:1475. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ellegaard KM, Brochet S, Bonilla-Rosso G, Emery O, Glover N, Hadadi N, Jaron KS, van der Meer JR, Robinson-Rechavi M, Sentchilo V, Tagini F, Engel P. 2019. Genomic changes underlying host specialization in the bee gut symbiont Lactobacillus Firm5. Mol Ecol 28:2224–2237. doi: 10.1111/mec.15075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vuong HQ, McFrederick QS. 2019. Comparative genomics of wild bee and flower isolated Lactobacillus reveals potential adaptation to the bee host. Genome Biol Evol 11:2151–2161. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evz136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Näpflin K, Schmid-Hempel P. 2018. Host effects on microbiota community assembly. J Anim Ecol 87:331–340. doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.12768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bisanz JE, Enos MK, Mwanga JR, Changalucha J, Burton JP, Gloor GB, Reid G. 2014. Randomized open-label pilot study of the influence of probiotics and the gut microbiome on toxic metal levels in Tanzanian pregnant women and school children. mBio 5:e01580-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01580-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kwong WK, Engel P, Koch H, Moran NA. 2014. Genomics and host specialization of honey bee and bumble bee gut symbionts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:11509–11514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405838111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McFrederick QS, Vuong HQ, Rothman JA. 2018. Lactobacillus micheneri sp. nov., Lactobacillus timberlakei sp. nov. and Lactobacillus quenuiae sp. nov., lactic acid bacteria isolated from wild bees and flowers. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Olofsson TC, Alsterfjord M, Nilson B, Butler E, Vasquez A. 2014. Lactobacillus apinorum sp. nov., Lactobacillus mellifer sp. nov., Lactobacillus mellis sp. nov., Lactobacillus melliventris sp. nov., Lactobacillus kimbladii sp. nov., Lactobacillus helsingborgensis sp. nov. and Lactobacillus kullabergensis sp. nov., isolated from the honey stomach of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 64:3109–3119. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.059600-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Corby-Harris V, Maes P, Anderson KE. 2014. The bacterial communities associated with honey bee (Apis mellifera) foragers. PLoS One 9:e95056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Avigad G, Dey PM. 1997. Carbohydrate metabolism: storage carbohydrates, p 143–204. In Dey PM, Harborne JB (ed), Plant biochemistry. Elsevier, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hladun KR, Smith BH, Mustard JA, Morton RR, Trumble JT. 2012. Selenium toxicity to honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) pollinators: effects on behaviors and survival. PLoS One 7:e34137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kirkwood JS, Miranda CL, Bobe G, Maier CS, Stevens JF. 2016. 18O-tracer metabolomics reveals protein turnover and CDP-choline cycle activity in differentiating 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes. PLoS One 11:e0157118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Plateau P, Saveanu C, Lestini R, Dauplais M, Decourty L, Jacquier A, Blanquet S, Lazard M. 2017. Exposure to selenomethionine causes selenocysteine misincorporation and protein aggregation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Sci Rep 7:44761. doi: 10.1038/srep44761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhao J, Zhou R, Hui K, Yang Y, Zhang Q, Ci Y, Shi L, Xu C, Huang F, Hu Y. 2017. Selenite inhibits glutamine metabolism and induces apoptosis by regulating GLS1 protein degradation via APC/C-CDH1 pathway in colorectal cancer cells. Oncotarget 8:18832–18847. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vance DE. 1990. Phosphatidylcholine metabolism: masochistic enzymology, metabolic regulation, and lipoprotein assembly. Biochem Cell Biol 68:1151–1165. doi: 10.1139/o90-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Choi J, Zhang W, Gu X, Chen X, Hong L, Laird JM, Salomon RG. 2011. Lysophosphatidylcholine is generated by spontaneous deacylation of oxidized phospholipids. Chem Res Toxicol 24:111–118. doi: 10.1021/tx100305b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]