ABSTRACT

Collective invasion, the coordinated movement of cohesive packs of cells, has become recognized as a major mode of metastasis for solid tumors. These packs are phenotypically heterogeneous and include specialized cells that lead the invasive pack and others that follow behind. To better understand how these unique cell types cooperate to facilitate collective invasion, we analyzed transcriptomic sequence variation between leader and follower populations isolated from the H1299 non-small cell lung cancer cell line using an image-guided selection technique. We now identify 14 expressed mutations that are selectively enriched in leader or follower cells, suggesting a novel link between genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity within a collectively invading tumor cell population. Functional characterization of two phenotype-specific candidate mutations showed that ARP3 enhances collective invasion by promoting the leader cell phenotype and that wild-type KDM5B suppresses chain-like cooperative behavior. These results demonstrate an important role for distinct genetic variants in establishing leader and follower phenotypes and highlight the necessity of maintaining a capacity for phenotypic plasticity during collective cancer invasion.

KEY WORDS: Metastasis, Lung cancer, RNA-seq, Mutation, Epigenetic, Plasticity

Summary: Image-guided capture and sequencing of invasive cancer cells reveals novel leader- and follower-specific gene mutations, highlighting an important relationship between genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity during collective invasion.

INTRODUCTION

Metastatic disease is the cause of 90% of deaths among cancer patients (Mehlen and Puisieux, 2006). In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which comprises 80–85% of all lung cancer diagnoses, metastases are commonly observed in the bones, lungs, brain, liver and adrenal glands. Patients presenting with metastatic disease have significantly worse prognoses than those with early-stage disease; for example, the 5-year survival rate for stage I NSCLC is 55%, while stage IV disease (in which distant metastases are present) carries a mere 4% five-year survival rate (Siegel et al., 2017). Successful colonization of distant sites requires that cells from the primary tumor gain the capacity to invade through the surrounding basement membrane, travel through the bloodstream or lymphatic system, and ultimately expand to establish colonies at the metastatic site (Leber and Efferth, 2009; Fidler, 2003).

Cells migrate through the microenvironment via multiple mechanisms. A classic example is the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), where cells lose epithelial features, such as expression of E-cadherin, and gain mesenchymal features, including expression of vimentin and N-cadherin. This shift is thought to promote cellular detachment and enable cancer cells to undergo single-cell invasion. In contrast, collective cell migration refers to the coordinated movement of a group of cohesive cells (Friedl and Gilmour, 2009). This phenomenon is well-described in embryonic development and wound healing, and histological evidence from primary patient tumor samples (Westcott et al., 2015; Cheung et al., 2013; Kabla, 2012; Friedl et al., 2012; Ewald et al., 2012), mouse models of metastasis (Gilbert-Ross et al., 2017; Richardson et al., 2018) and 3D cultures (Friedl et al., 1995; Hegerfeldt et al., 2002; Nabeshima et al., 1999; Cheung et al., 2013; Konen et al., 2017; Leighton et al., 1960) suggest that cells from solid tumors often also migrate and invade in cohesive packs. These collective invasion packs and streams vary in width, shape and cell number, as well as in the mechanisms guiding their movement (Friedl, 2004; Alexander et al., 2008; 2013; Friedl and Wolf, 2010; Haeger et al., 2014; van Zijl et al., 2011; Pandya et al., 2017).

Understanding the mechanisms that underlie the outgrowth of metastatic clones is further complicated by the heterogeneous mix of cell populations within each tumor. This intratumor heterogeneity arises from cell-to-cell variation in the genetic background, each expanding to create a unique subclonal population (McGranahan and Swanton, 2017). Superimposed upon this subclonal genomic heterogeneity is the potential for epigenetic heterogeneity reflected in variations in gene expression even among genetically identical cells. Recently, multiregional sequencing of primary lung tumors characterized the intratumor heterogeneity of NSCLC and showed that upwards of 24% to 30% of mutations went undetected in at least one sampling region, demonstrating that almost a third of mutations are occurring in spatially distinct subclonal populations and may have been missed in broad-scale data based on single sampling, such as those analyzed as part of the TCGA project (de Bruin et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). These unique subpopulations may be endowed with properties that enhance attributes beneficial to tumor cells, such as resistance to drug therapy, or the ability to invade and metastasize (Waclaw et al., 2015; Lipinski et al., 2016; McPherson et al., 2016; Campbell et al., 2010). For instance, the clonal profile of metastatic disease often does not reflect the profile of the primary tumor, but instead includes one or just a few subpopulations from the primary site (McPherson et al., 2016; Rinner et al., 2012; Gerlinger et al., 2012; Cheung et al., 2016).

One example of phenotypic heterogeneity associated with invasive behavior includes rare specialized leader cells that lead collective invasive packs, and follower cells that adhere to and follow behind the leaders, both of which cooperate to achieve collective invasion (Konen et al., 2017; Cheung et al., 2013; Westcott et al., 2015; Haeger et al., 2015; Pandya et al., 2017). We developed a novel platform (Spatiotemporal Genomic and Cellular Analysis; SaGA) to isolate specific leader and follower cell populations from collectively invading NSCLC cells (Konen et al., 2017). Characterization of these cell types revealed that isolated follower cells are highly proliferative but poorly invasive, while isolated leader cells are highly invasive, but poorly proliferative (Konen et al., 2017). These cellular subtypes cooperate through an atypical angiogenic signaling pathway that is dependent upon VEGF. These previous data suggest a symbiotic relationship, in which both leader and follower cells are necessary for collective invasion to proceed successfully; however, key questions remain as to what drives the biology and emergence of leader and follower cells from a tumor cell population.

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the role of genetic heterogeneity on collective invasion. We analyzed invading leader and follower populations arising from a common H1299 parental NSCLC cell line grown as 3D spheroids. Strikingly, this revealed mutational landscapes that differ significantly between leader and follower cells, including several expressed mutations that were found exclusively in one cell type or the other. To our knowledge this is the first identification of leader- and follower-specific gene mutations within the same collectively invading tumor cell population.

RESULTS

Leader and follower cell populations contain distinct mutational profiles

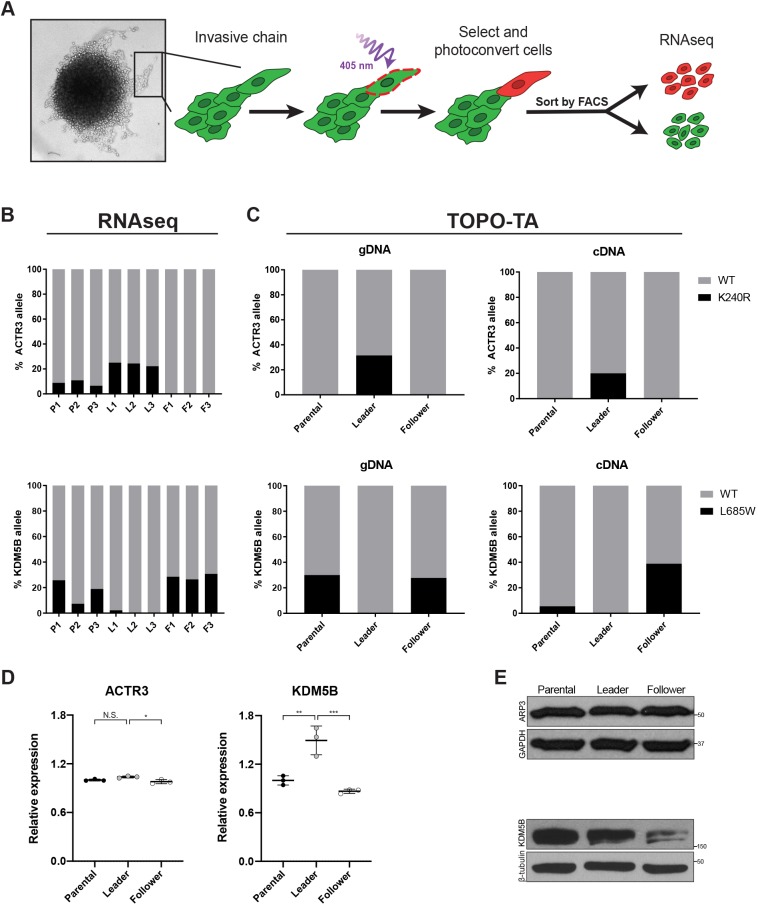

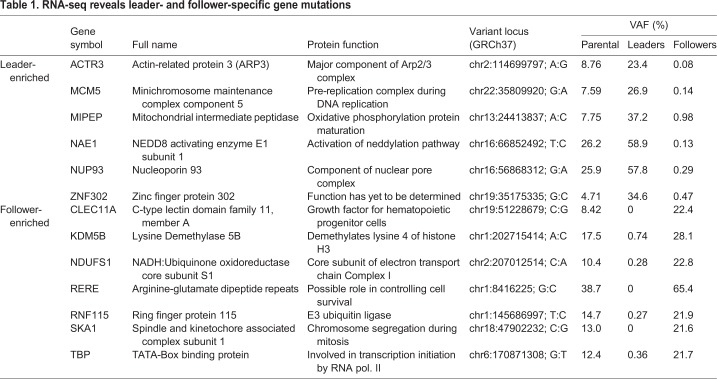

We previously developed the SaGA technique for isolation of leader and follower cells from collectively invading packs of human NSCLC cancer cells (Konen et al., 2017). Briefly, cells expressing the Dendra2 green-to-red photoconvertible fluorescent protein are formed into multicellular spheroids, embedded in Matrigel and allowed to invade for 24 h. Leader or follower cells are then selected based upon physical positioning within invasive chains, optically highlighted by photoconversion using a 405 nm laser and separated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Fig. 1A). By using this approach, we isolated three follower populations and two leader populations from H1299 parental cells. Following expansion of each population in 2D culture, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed in triplicate, using three separate passages of parental H1299 cells, the three separately isolated populations of follower cells and the two separately isolated populations of leader cells (including two passages of one of the leader populations). Sequence variants were determined for each population (leader, follower or parental) independently by mapping the RNA-seq profiles to human reference genome Hg19 (GRCh37), resulting in a total of 6240 filtered variants combined in the three populations (see Materials and Methods for details). Notably, when comparing variant allele frequencies (VAF) via pairwise t-test analysis, a number of variants were disproportionately present in the leader versus follower populations. We therefore further filtered for those variants that exhibited >20% VAF in either leaders or the followers and <1% in the other (VAF P<0.01 between leaders and followers; Student's t-test). For the purposes of this study, we further excluded those located in 5′ or 3′ UTRs and known SNPs. Application of these criteria identified 14 missense mutations – six were leader specific and eight follower specific (Table 1). This represents the first identification of leader- and follower-specific mutations within the collective invasion pack.

Fig. 1.

ARP3 K240R and KDM5B L685W are validated mutations in H1299 leader and follower cells. (A) Schematic of the SaGA protocol used to isolate leader and follower cell populations. (B) Variant allele frequencies for ACTR3 and KDM5B from RNA-seq of H1299 parental (P), leader (L) and follower (F) cells. n=3 separate populations per group. (C) TOPO-TA cloning and subsequent Sanger sequencing confirms the presence of ARP3 K240R and KDM5B L685W mutations in both cDNA and genomic DNA (gDNA) from parental, leader and follower cells, respectively. n=20 colonies (ARP3 parental, follower gDNA and parental, leader cDNA and KDM5B parental gDNA); 19 colonies (ARP3 leader gDNA and KDM5B leader gDNA); 18 colonies (ARP3 follower cDNA and KDM5B follower gDNA and parental, follower cDNA); and 17 colonies (KDM5B leader cDNA). Association between the genotype and cell phenotype was determined by Fisher's exact test as follows: mutant versus wild type, leader versus follower ARP3 gDNA P=0.008, ARP3 cDNA P=0.11, KDM5B gDNA P=0.02, and KDM5B cDNA P=0.008. (D) Relative mRNA expression (via RNA-seq; normalized to parental average) and (E) protein levels (via western blotting) of ACTR3 (ARP3) and KDM5B in H1299 parental, leader, and follower populations. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; N.S., not significant (one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test).

Table 1.

RNA-seq reveals leader- and follower-specific gene mutations

Given the cell type specificity, we hypothesized that these mutations could be key contributors to the emergence of leader versus follower phenotypes from the parental population. To test this, we chose two candidate mutations for further study – one leader-enriched, ACTR3 chr2:114699797 A to G, which results in a mutation in ARP3 at K240 (ARP3 K240R), and one follower-enriched, KDM5B chr1:202715414 A to C, resulting in a mutation at L685 (KDM5B L685W) (Fig. 1B). We first confirmed these mutations by Sanger sequencing of genomic DNA and cDNA from the parental H1299 population, as well as the isolated leader and follower populations (Fig. S1). Both variants were detectable at subclonal levels in genomic DNA, indicating that they were unlikely to have arisen de novo during transcription, but represented a subpopulation of genomic alleles in the parental population. Moreover, the selectivity for the leader or follower population observed at the RNA levels was preserved at the genomic DNA level (Fig. S1; Fig. 1C). Analysis of ARP3 and KDM5B expression in H1299 parental, leader and follower cells showed that ARP3 mRNA and protein levels were comparable between the populations (Fig. 1D,E). KDM5B mRNA and protein were significantly reduced in follower cells relative to leaders (Fig. 1D,E). Despite the reduced overall levels, KDM5B mRNA in follower cells retained the ∼2:1 ratio of wild type versus mutant observed at the genomic DNA level (Fig. 1C) suggesting that the follower-enriched KDM5B L685W mutation is expressed. Similarly, while there was some variation in the frequency of both mutations in the parental population between methods and DNA/RNA samples isolated at different times, there was little variation in the allelic balance in leader and follower populations, which maintained a consistent frequency of their respective mutations at both DNA and RNA level, suggesting that there is no allelic bias in the expression of the mutant version in either case. Thus, our selection of leader and follower cells based on phenotypic criteria also selected for subpopulations with distinct allelic balance of expressed mutations.

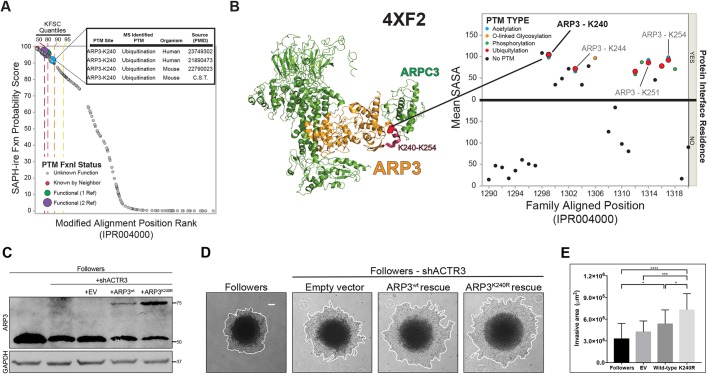

Predicted functional impact of the leader-enriched ARP3 K240R mutation

We next sought to characterize the potential impact of the observed mutations. We started with the leader-enriched ACTR3 mutation, which results in a K to R shift in ARP3 (K240R). ARP3 is a key component of the Arp2/3 complex that helps facilitate cellular migration by promoting lamellipodia protrusion (Goley and Welch, 2006). Overexpression of ARP3 has been correlated with invasion, metastasis and poor survival in multiple cancer types, including gastric, colorectal, liver and gallbladder (Zheng et al., 2008; Iwaya et al., 2007; Lv et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2013). Furthermore, several mass spectrometry studies have indicated that ARP3 K240 is a post-translational modification (PTM) site, with evidence of both ubiquitylation and acetylation (Mertins et al., 2013; Wagner et al., 2011, 2012) (Fig. 2A, inset). To evaluate the functional impact of the K240R mutation on the ARP3 protein, we used Structural Analysis of PTM Hotspots (SAPH-ire) (Torres et al., 2016), which predicts the functional potential of PTMs in protein families that have existing experimental and 3D structure data. SAPH-ire calculates a Function Probability Score (FPS) using a neural network model trained with an array of protein sequence and PTM-specific features extracted from PTMs with established functional impact. Consistent with these data, K240 had among the highest FPS values of all known modified residues within the ARP3 protein family and was among the top 90% of PTMs with well-established functional significance (i.e. in four or more publications) across all protein families (Fig. 2A). SAPH-ire also revealed six experimental ubiquitylation sites in the ARP3 protein family between residues alignment positions 1298–1315, four of which correspond to ubiquitylation of ARP3 specifically (K240, K244, K251 and K254). Of these, K240 had the highest mean solvent accessible surface area (SASA) and was also proximal to a protein interaction interface (Fig. 2B). The high solvent accessibility, proximity to a protein–protein interaction interface, and predicted functional impact of the ARP3 K240 site suggest that this mutation could indeed be altering the activity of ARP3 in leader cells.

Fig. 2.

PTM hotspot analysis of ARP3 K240 suggests that the K240R mutation has a functional impact. (A) Plot of SAPH-ire probability score by rank for all modified alignment positions in the ARP protein family IPR004000. The ARP3 K240 ubiquitylation site is highly ranked along with other MAPs that contain PTMs with well-established function (four or more supporting references), as indicated by known function source count (KFSC) quantiles. Inset, table of ARP3 K240 PTMs identified by mass spectrometry of human and mouse tissues, including literature sources. (B) Local PTM topology of the ARP3 family near ARP3 K240. PTM sites plotted by solvent accessible surface area (SASA) and proximity to the interface of a protein–protein interaction. Human ARP3 PTMs are labeled, revealing multiple ubiquitylation sites between K240 and K254. Left, structure of the Arp2/3 complex (PDB 4XF2) indicating ARP3 K240 (spheres) within the K240–K254 region of ARP3 (red). (C) Western blot showing exogenous (upper band) versus endogenous (lower band) ARP3 expression in unmodified followers, and shACTR3-expressing followers rescued with either empty vector (EV), wild-type ARP3 (ARP3wt), or ARP3K240R. Rescue constructs were mCherry-tagged to allow for visualization within invasive chains. (D) Images of invasion in Matrigel at 24 h of spheroids comprised of unmodified follower cells, or shACTR3-expressing followers transfected with either empty vector, wild-type ARP3, or ARP3 K240R constructs. The edge of the spheroid is highlight by a white line. (E) Quantification of spheroid invasive area (mean±s.d., n=17, 15, 16, and 17 spheroids per group, respectively, across N=3 experiments). *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test). Scale bar: 100 µm.

ARP3 K240R promotes invasion and leader cell behavior

We next sought to determine the function of the leader-specific ACTR3 mutation by introducing this mutation into a follower cell background and determining the impact on collective invasion and the outgrowth of cells with leader behavior. Given the relatively low VAF (23.4%) of mutant ACTR3 in leader cell DNA and RNA, we sought to replicate the leader cell ACTR3 allelic balance by employing a rescue approach. ARP3 levels were first stably knocked down using two separate short hairpin RNAs (Fig. S2A,B), including one (shACTR3 #2) targeted to the 5′ UTR of endogenous ACTR3. Knockdown of ARP3 significantly reduced 3D invasion in H1299 parental, leader and follower cells compared to pLKO.1 controls (Fig. S2C,D). Using a sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay to measure cell growth, we found little difference upon ARP3 knockdown until 96 h in the leader and follower populations, and 120 h in the parental population, when proliferation was decreased (Fig. S2E).

To test the functional consequences of ARP3 mutation, follower cells expressing shACTR3 #2 were then ‘rescued’ by stably expressing empty vector, mCherry-tagged wild-type ARP3 or mCherry-tagged ARP3 K240R, under the control of the moderate activity UBC promoter (Qin et al., 2010). Higher expression was achieved for ARP3 K240R than wild-type ARP3 (Fig. 2C, upper bands), suggesting that ARP3 K240R may be more stable than the wild-type protein. When grown as a spheroid, embedded in a Matrigel matrix, and allowed to invade for 24 h (Fig. 2D), ARP3-knockdown follower cells reconstituted with ARP3 K240R, and to a lesser extent those reconstituted with wild-type ARP3, exhibited significantly higher invasive area compared with unmodified followers or those reconstituted with empty vector (Fig. 2E). This indicates that ARP3 expression, and especially ARP3 K240R expression, can increase invasive capacity even in normally poorly invasive follower cells.

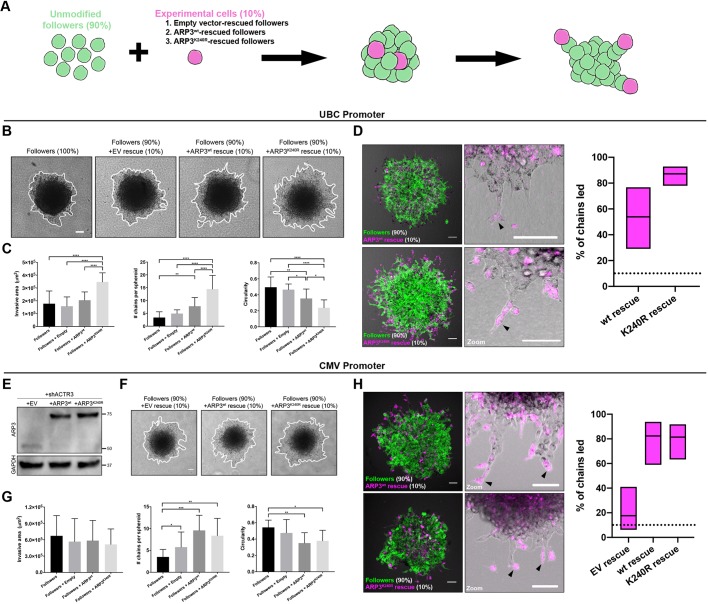

Next, we sought to examine whether ARP3 K240R could specifically promote leader cell behavior (i.e. facilitate collective invasion and travel at the front of invasive chains) in a heterogeneous population. We created 3D spheroids comprised of 90% unmodified H1299 followers and 10% ARP3-depleted followers rescued with either empty vector, wild-type ARP3 or ARP3 K240R (Fig. 3A). After 24 h embedded in Matrigel, we observed a significant increase in invasive area and average number of chains per spheroid, and decreased circularity (indicating more chain-like and less sheet-like invasion) in the mixed spheroids containing 10% ARP3 K240R-rescued followers, as compared with the other three conditions (Fig. 3B,C). To determine whether the ARP3 K240R-rescued followers were in fact leading these invasive chains, we used confocal fluorescence imaging to quantify the fraction of chains that exhibited mCherry–ARP3 K240R-rescued followers in the leader position. In spheroids containing 10% wild-type ARP3-rescued followers, we found rescued cells in the leader position in 53.8% of those chains (95% c.i. of 29.1% to 76.8%; Fig. 3D). By contrast, in spheroids containing 10% ARP3 K240R-rescued followers, rescue cells were found in the leader position in 87.2% of chains (95% c.i. of 78.0% to 92.9%; Fig. 3D). Thus, while both wild-type ARP3-rescued and ARP3 K240R-rescued cells led chains at a higher frequency than expected by random chance, the ARP3 K240R-rescued cells were more efficient in this regard. Together, these data indicate that ARP3 K240R confers key leader-like behaviors onto follower cells, including increased invasive capacity, increased numbers of invasive chains and a greater ability to lead those chains.

Fig. 3.

ARP3 K240R confers leader-like properties when expressed in follower cells. (A) Illustration of spheroid-mixing experimental setup. Spheroids comprised either 100% unmodified followers, or 90% unmodified followers plus 10% of shACTR3-expressing followers rescued with either empty vector, wild-type ARP3 (ARP3wt) or ARP3 K240R (ARP3K240R). (B) Invasion of mixed spheroids in Matrigel after 24 h. Rescue constructs were expressed under the control of the UBC promoter. Representative images shown for each condition. The edge of the spheroid is highlight by a white line. (C) Quantification of invasive area, circularity and average number of chains per spheroid for each condition (mean±s.d., n=14, 11, 18 and 16 spheroids for unmodified followers, EV rescue, wild-type ARP3 rescue, and ARP3 K240R rescue, respectively, across N=3 experiments). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test). (D) Confocal fluorescence imaging of mixed spheroids, with unmodified followers shown in green and mCherry-ARP3 K240R-rescued cells or mCherry-wild-type ARP3-rescued cells shown in magenta. Black arrowheads indicate invasive chains being led by experimental rescue cells. Graphs show percentage of chains (mean±95% c.i.) led by wild-type ARP3-rescued and ARP3 K240R-rescued followers. The dotted line denotes the level at which 10% of chains are led, corresponding to the proportion of ARP3-rescued cells in the mixed spheroids. (E) Western blot showing protein expression levels of ARP3 in followers after knockdown of endogenous ARP3 and rescue with empty vector (EV), wild-type ARP3 or ARP3 K240R. Rescue constructs were expressed under control of the CMV promoter. (F,G) 24 h invasion of mixed spheroids in Matrigel. Representative images (F) and quantification (G) of invasive area, circularity and average numbers of chains per spheroid shown for each condition (mean±s.d., n=12, 12, 12 and 11 spheroids per group, respectively, across N=2 experiments). In F, the edge of the spheroid is highlight by a white line. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test). (H) Confocal fluorescence imaging of mixed spheroids, with unmodified followers shown in green and mCherry-wild-type ARP3-rescued cells or mCherry-ARP3 K240R-rescued cells shown in magenta. Black arrowheads indicate invasive chains being led by experimental rescue cells. Graphs show the percentage of chains (mean±95% c.i.) led by mCherry-empty-vector-rescued, wild-type ARP3-rescued and ARP3 K240R-rescued followers. The dotted line denotes the proportion of ARP3 rescued cells in the mixed spheroids, thus the 10% of chains expected to be led based on random chance. Scale bars: 100 µm.

As noted above, the K240R-reconstituted ARP3 knockdown cells express higher levels of ARP3 than those reconstituted with wild-type ARP3. To distinguish the impact of ARP3 dosage from that of ARP3 K240R mutation, we re-created the same rescue cell lines using a CMV promoter (Fig. 3E) and repeated the above experiments creating mixed spheroids with 10% rescued cells (Fig. 3F). At this higher protein expression level, there was no significant difference in invasive area between the groups (Fig. 3G). Additionally, while chain number increased and circularity decreased in spheroids containing either wild-type ARP3-rescued or ARP3 K240R-rescued followers (Fig. 3G), there was no significant difference between the two, suggesting that the functional difference between ARP3 K240R and wild-type ARP3 is mitigated at higher expression levels. Furthermore, both wild-type ARP3-rescued followers (81.5% of chains led; 95% c.i. of 63.3% to 91.8%) and ARP3 K240R-rescued followers (84.2% of chains led; 95% c.i. of 62.4% to 94.5%) promoted leader cell behavior when mixed with 90% unmodified followers (Fig. 3H). The specificity of the effect was further confirmed by mixing experiments with mCherry empty vector-rescued follower cells, which led only 17.7% of chains (95% c.i. of 6.19% to 41.0%; Fig. 3H), suggesting that the enhanced leader ability of the ARP3 K240R cells was not simply due to the different cell types segregating within the spheroid. Based upon these findings, it appears that an increased dosage of ARP3 is sufficient to promote leader-like behavior, and that the selective ability of ARP3 K240R to lead invasive chains and drive collective invasion at lower expression levels may arise, in part, from increased effective dose of ARP3 protein.

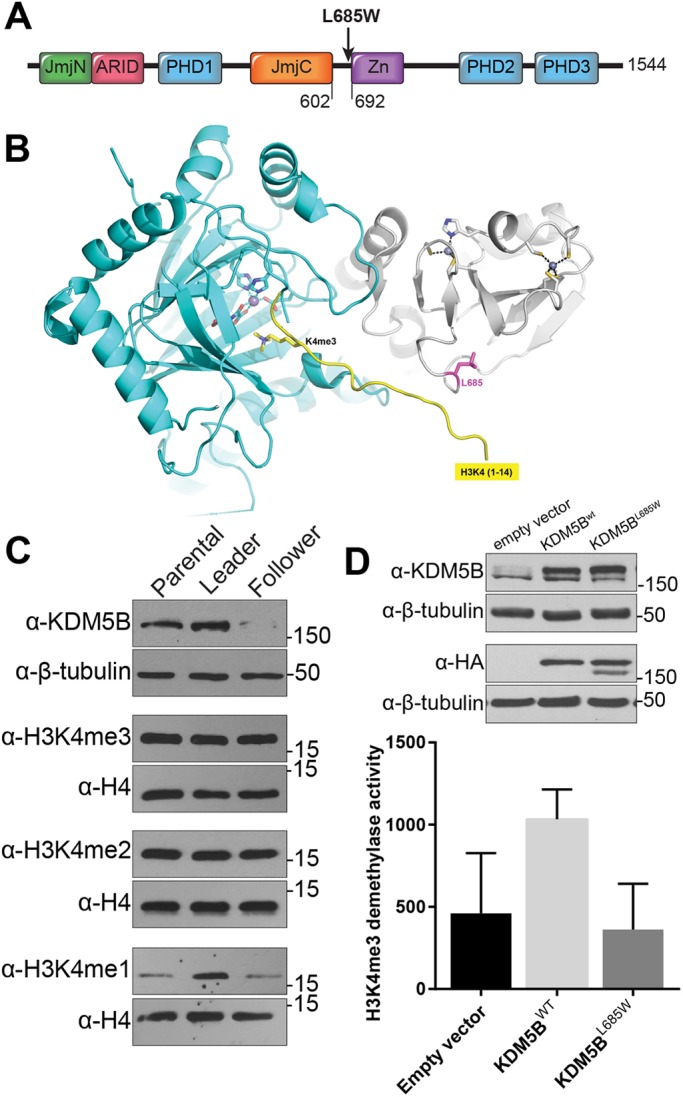

Functional impact of the follower-enriched KDM5B L685W mutation

Subsequently, we sought to assess the effects of a follower-specific mutation on collective invasion. As noted above, the KDM5B L685W mutation was selectively expressed in the parental and follower populations but was absent from the leader population (Fig. 1B). KDM5B is a lysine demethylase that catalyzes the removal of di- and trimethylation from histone H3 methylated at K4 (H3K4me2, H3K4me3). As an epigenetic regulator, KDM5B is uniquely situated among the identified mutations to influence multiple pathways directly involved in guiding invasive behavior (Table 1) (Han et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2019; Tam and Weinberg, 2013). Indeed, KDM5B has been implicated in the regulation of invasive and migratory behavior across many cancer types, including hepatocellular, gastric, breast, lung and prostate (Tang et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Bamodu et al., 2016; Viré et al., 2014; Kuo et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2015). The point mutation observed in followers results in a L685W substitution and lies in close proximity to the KDM5B zinc finger domain, a region necessary for demethylase activity in vitro and in cells (Horton et al., 2016a; Yamane et al., 2007) (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, structural modeling of KDM5B bound to the histone H3 tail showed that residue 685 sits in a hydrophobic pocket within KDM5B, near the binding site of the N-terminal tail of histone H3 (Fig. 4B). As a tryptophan residue has a much bulkier sidechain than a leucine residue, the introduction of this large aromatic sidechain has the potential to alter or disrupt the interaction of KDM5B with histone H3 (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of the follower-enriched KDM5B L685W mutation. (A) Diagram of KDM5B protein domains and relative position of amino acid residue 685 to the zinc finger domain. (B) Partial model of KDM5B L685W with the H3 N-terminal tail (residues 1–14). The model was generated by superimposing a structure of KDM5B (PDB 5A1F) with that of KDM6A in complex with histone H3 peptide (PDB 3AVR), which placed a trimethylated H3K4 in the active site of KDM5B, near the Fe(II)-binding site, and the C-terminal tail of histone H3 near L685. (C) Western blot analysis of KDM5B expression and mono, di- and tri-methylated H3K4 in lysates from H1299 parental, leader, and follower cell populations. Loading controls β-tubulin and H4 are probed from the same blot as preceding bands. The experiment was repeated on three separate protein collections from cells at different passages (N=3). (D) In vitro H3K4 demethylation assay performed on lysates derived from three separate, biological replicates of parental H1299 cells expressing empty vector, wild-type KDM5B (KDM5BWT) or KDM5B L685W (mean±s.d. specific activity; N=3 biological replicates).

Overall, the follower cells expressed less KDM5B protein than leader cells or the parental H1299 population (Figs 1E and 4C), and, as noted above, at least a fraction of those follower cells, if not all (see below), would be expected to harbor the L685W mutation. Comparison of the global levels of the KDM5 substrates showed that while H3K4me2 and me3 were similar across populations, follower cells had reduced global levels of H3K4 monomethylation (H3K4me1), the end-product of KDM5B catalytic activity, suggesting reduced cellular H3K4 demethylase activity in follower cells versus leader cells (Fig. 4C). To test this directly, we generated parental H1299 cells stably overexpressing HA-tagged wild-type KDM5B or KDM5B L685W and performed in vitro demethylation assays on cell lysates (Fig. 4D). Whereas overexpression of wild-type KDM5B trended toward increased cellular H3K4 demethylation activity by ∼2-fold, overexpression of KDM5B L685W had no impact on endogenous H3K4 demethylation activity despite similar levels of wild-type and mutant expression (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these data indicate that the KDM5B L685W mutation seen in the followers is associated with reduced cellular KDM5 activity.

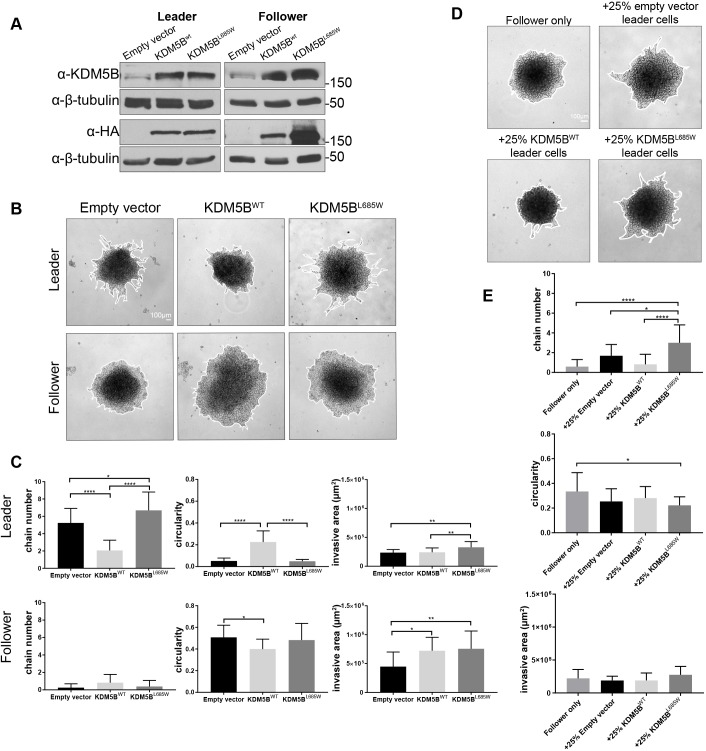

KDM5B L685W modulates collective invasion by tipping the balance towards follower cell behavior

The above data suggest that KDM5B L685W may confer a partial loss of function or decreased activity on the follower cells, and further that this mutation is selected against in the leader population (addressed in more detail below). We therefore sought to determine how the expression of the L685W might behave in the context of an otherwise wild-type KDM5B background (to mimic the mixed genotype observed in followers) by expressing KDM5B L685W in leader cells and determining the impact on collective invasion in 3D spheroid culture (Fig. 5A,B). Interestingly, overexpression of wild-type KDM5B in leader cells suppressed their propensity for chain-like invasion, as indicated by an increase in circularity and a decrease in the number of chains relative to cells expressing empty vector (Fig. 5B,C). However, invasive area was similar between leaders expressing empty vector and wild-type KDM5B, suggesting that the wild-type KDM5B-expressing leaders retain invasive capabilities but lose some of the collective (cooperative) behavior manifested as chain-like invasion. By contrast, overexpression of the KDM5B L685W mutant enhanced slightly the chain-like invasion, with spheroid behavior resembling the high chain number and low circularity observed in empty vector-expressing leader cells (Fig. 5B,C).

Fig. 5.

Wild-type KDM5B suppress and KDM5B L685W drives chain-like invasion. (A) Western blot analysis demonstrating successful expression of HA-tagged wild-type (WT) and L685W KDM5B in leader and follower cell populations. (B) Images of invasion in Matrigel at 24 h of leader and follower spheroids expressing empty vector, wild-type HA–KDM5B or HA–KDM5B L685W. (C) Quantification of invasive area, circularity and chain number from spheroids depicted in B [mean±s.d., n=16 spheroids (follower empty vector, leader KDM5BWT, and leader KDM5BL685W), n=17 spheroids (leader empty vector and follower KDM5BWT), n=18 spheroids (follower KDM5BL685W), across N=3 independent experiments]. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test). (D) Images of invasion in Matrigel at 24 h of spheroids composed of 75% follower cells and 25% leader cells expressing either empty vector, wild-type HA–KDM5B, or HA–KDM5B-L685W. The edges of the spheroids are highlight by a white line in B and D. (E) Quantification of invasive area, circularity and chain number from spheroids depicted in D [mean±s.d., n=16 spheroids (+25% leader empty vector), n=17 spheroids (follower only and +25% leader KDM5BWT), n=18 spheroids (+25% leader KDM5BL685W), across three independent experiments]. *P<0.05, ****P<0.0001 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test).

To reconcile these findings, we considered the possibility that heterogeneity in KDM5B expression and/or activity might be required for cells in a population to take on the cooperative roles necessary to form an invasive chain. Even in spheroids derived from a purified leader population, such as those shown above, there must be at least some cells that take the trailing position, or evolve follower-like behavior, even in the absence of new genetic events. One interpretation of the above data is that overexpression of wild-type KDM5B may prevent the emergence of cells with follower behavior, thus suppressing chain-like cooperative behavior; by pushing the balance even further towards high KDM5B activity, the reduced population plasticity might decrease the probability that cells can take on the follower role. By contrast, overexpression of KDM5B L685W might allow for greater variation in KDM5B activity, promoting heterogeneity and the emergence of cells with follower behavior, further enhancing collective behavior. If this is the case, then one might predict that ectopic expression of wild-type KDM5B or KDM5B L685W would have relatively little impact on follower cells, which on their own do not exhibit significant cooperative behavior. Indeed, when expressed in follower cells, the further expression of KDM5B or KDM5B L685W had a negligible impact on circularity or the chain number of follower-only spheroids (Fig. 5B,C). These data also indicate that increasing the concentration of wild-type KDM5B is in itself not sufficient to impose leader behavior on follower cells.

The benchmark test for leader cell activity is to determine how such cells behave when mixed with followers in 3D invasion assays. As noted above for ARP3, leader cells can have a strong effect on chain formation, even when they make up a very small proportion of the total cells in a spheroid. We therefore tested directly how expression of KDM5B L685W affects the ability to lead in a heterogenous population by creating mixed spheroids comprised of predominantly (75%) unmodified follower cells into which leader cells overexpressing wild-type KDM5B or KDM5B L685W (25%) had been added, and monitoring chain-like invasion (Fig. 5D,E). We found again that even in the context of unmodified followers, overexpression of wild-type KDM5B suppressed chain-like behavior relative to control (vector only) leaders. In contrast, expression of KDM5B L685W not only retained but even somewhat enhanced the ability of cells to lead invasive chains compared to those expressing either empty-vector or wild-type KDM5B (Fig. 5D,E). These data suggest that overexpression of KDM5B L685W sustains chain-like cooperative behavior. Taken together, these data support the idea that wild-type KDM5B supports the leader phenotype in part by suppressing emergence of follower-like behavior, while expression of the L685W mutant supports, and even somewhat promotes chain-like invasion.

To further test the impact of KDM5B L685W population heterogeneity on collective invasion, we mixed leader lines expressing empty vector, wild-type KDM5B and KDM5B L685W with unmodified leaders expressing mCherry at different proportions and monitored chain-like invasion in 3D spheroids (Fig. S3). As both lines already express Dendra2, we quantified the fraction of chains led by red/magenta-positive cells (mCherry, unmodified leaders) or green-only cells (KDM5B modified lines) (Fig. S3B). We found that overexpression of wild-type KDM5B again suppressed chain formation in spheroids (Fig. S3E, 100% KDM5B WT) relative to empty vector, which was recovered proportionally as the fraction of unmodified leaders in the spheroid increased (Fig. S3E). Despite this suppression in total chains, the fraction that were led by a green-only, wild-type KDM5B-overexpressing leader was roughly proportional to their abundance in the mixed spheroid (compare Fig. S3 panels D and E, 90% versus 10% wild-type KDM5B). By contrast, leaders expressing L685W showed no suppression of chain-like behavior relative to vector-only cells (Fig. S3E, 100% KDM5B L685W), and exhibited a similar frequency of green-only versus magenta (unmodified leaders) cells in the lead position regardless of their relative proportions. These data support the idea that overexpression of wild-type KDM5B may suppress the emergence of cooperative behavior necessary to form a chain, such cells nevertheless retain the capacity to lead in a mixed population.

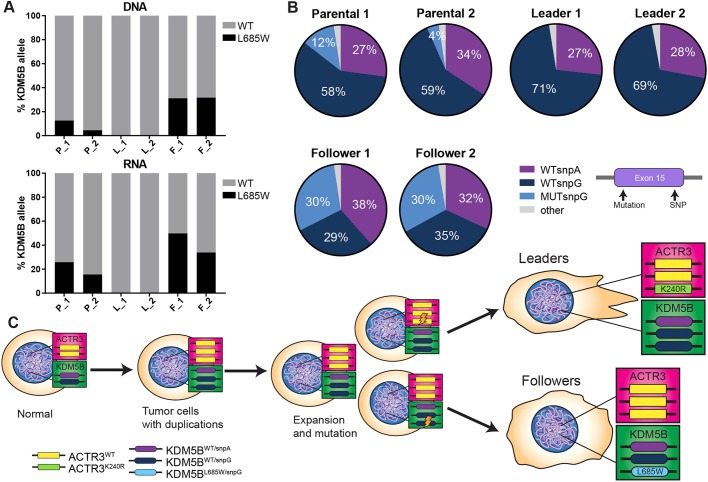

SNP analysis suggests distinct leader and follower cell lineages

If high expression of wild-type KDM5B enforces the leader phenotype and/or suppresses the emergence of an alternate phenotype (e.g. followers), and this has an impact on collective behavior, then one might predict that there would be a selection against the expression of KDM5B L685W in leader cells and selection for KDM5B L685W in follower cells independently captured from H1299 spheroids relative to the parental population. Fortuitously, a common SNP (rs1141108, chr1: 202715284, G to A) is located within the same exon as the KDM5B mutation, and the H1299 cell line was determined to be heterozygous for this SNP in our initial sequence analysis. Targeted deep resequencing of an amplicon including the region containing both the mutation (chr1:202715414) and the SNP (chr1: 202715284) in genomic DNA thus enabled us to trace the relationship between allelic balance and the frequency of the KDM5B L685W mutation in each cell population (average depth, 348,327 reads).

We first found that approximately one third of alleles in each population carried the A variant and two thirds carry the G variant at rs1141108, leading us to conclude that there are three copies of KDM5B and/or chromosome 1 in our strain of H1299 cells and that this ploidy is maintained across the three populations. The ACTR3 mutation that gives rise to ARP3 K240R on chromosome 2 also occurs in approximately one third of reads from genomic DNA in leader cells (Fig. 1B). Focal copy number alterations in the genomic regions surrounding ACTR3 and KDM5B have not been detected in H1299 cells by SNP copy number analyses (COSMIC Cell Lines Project: https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cell_lines). These data suggest that our strain of H1299 cells are functionally triploid. We further ascertained that the KDM5B variant (chr1:202715414: A>C) giving rise to the L685W mutation resides exclusively in cis with the SNP rs1141108 G allele (99.7% concordance across 267,414 total reads containing the mutation). The analysis further confirmed the proportions of KDM5B wild-type versus mutant alleles shown in Fig. 1, including the more variable mutation frequency observed among different isolates of the parental population, the complete absence of the KDM5B L685W mutation (<0.00001%) in the leader cells and the very consistent ∼30% of alleles with the KDM5B mutation in the follower cells (Fig. 6A). Additionally, the relative proportions of the wild-type and variant expressed at the mRNA level were largely reflective of the proportion at the genomic DNA level across all three populations, again suggesting that there was no allelic bias in expression of the wild-type versus mutant forms of KDM5B (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Leader and follower cells are derived from two separate populations defined by mutational profile. (A) Deep targeted resequencing across KDM5B exon 15 in genomic DNA (top) and RNA (bottom) isolated from parental, leader and follower populations (N=2 independent isolates of DNA or RNA at separate passages of cells derived from a single phenotypic isolation; average depth=348,327 reads per sample). (B) Pie charts depicting proportions of KDM5B genotypes across parental, leader and follower populations as determined from the deep amplicon sequencing shown in A. (C) Model of the potential history of leader and follower populations from parental cell population as inferred from the genetic profiles of KDM5B and ARP3.

The finding that the KDM5B L685W mutation was exclusive to the G allele while the A allele was exclusively wild-type allowed us to trace the relative proportions of the three genotypes (wild type/A, wild type/G and mutant/G) across the parental, leader and follower populations. These data showed that whereas 4–12% of the parental population carries the KDM5B mutant/G allele, this allele was excluded from the leader population, which exhibited essentially none of the KDM5B mutant/G alleles (Fig. 6B), but was nearly 2-fold enriched in the isolated followers (30%) (P=0.008; ANOVA plus Tukey's post-hoc correction) and approached the expected frequency (if each allele is independently sorted). Taken together, these data suggest that whereas the parental population varies in the fraction of cells containing the mutant/SNP G allele, growth in 3D culture, SaGA-based capture and subsequent expansion of leader cells selectively enriches for cells expressing only wild-type KDM5B, whereas that of followers selects for a population in which nearly every cell contains (and expresses) one copy of the mutant KDM5B L685W allele.

DISCUSSION

The greatest threat to cancer patient mortality is the metastatic spread of tumor cells from the primary site (Mehlen and Puisieux, 2006). Collective migration and invasion are major contributors to the dispersion of metastatic cancer cells (Friedl and Gilmour, 2009; Bronsert et al., 2014; Haeger et al., 2015; Mayor and Etienne-Manneville, 2016). Collective invasion is typified by the coordinated movement of a group of cohesive cells, often including multiple heterogeneous cell populations with specialized functions. One well-studied example of collective invasion is that of chain-like invasion, in which specialized leader cells lead groups of cells termed follower cells, out of the tumor (Konen et al., 2017; Mayor and Etienne-Manneville, 2016; Haeger et al., 2015), with both populations playing important roles in the process of invasion. Until now, studies of the distinct populations within invasive chains have been limited by the inability to separate these populations. Development of the SaGA technique (Konen et al., 2017), enabled us to independently analyze leader and follower cells with different phenotypes to gain insight into population dynamics and the emergence of populations that differ in cell behavior. Our results identify a set of expressed mutations that define leader and follower cells, representing, to our knowledge, the first known instance of distinct mutations as contributors to the leader and follower phenotypes within collectively invading packs.

We confirmed the importance of the leader cell-enriched mutation ARP3 K240R to the invasive leader cell phenotype by introducing it into a population of non-invasive H1299 follower cells. Both in pure spheroids and when mixed with 90% unmodified followers, ARP3 K240R-expressing followers displayed an increased ability to invade and lead collective chains at both lower and higher protein expression levels. Rescue with wild-type ARP3 also conferred leader cell behavior, but only when expressed at supra-physiological levels. One potential explanation is that ARP3 K240R increases the effective dosage of ARP3 protein, essentially recapitulating ARP3 overexpression even at low expression. Indeed, ARP3 K240R accumulated to higher levels than wild-type ARP3 when exogenously expressed from the same vector. The K240R mutation might interfere with ubiquitylation at K240, resulting in either decreased ARP3 turnover or enhanced ARP3 activity. Ubiquitylation at K240 has previously been observed by mass spectroscopy in multiple human cell lines as well as mouse tissue, and K240R was predicted by SAPH-ire to have a high likelihood of functional consequence. Further experiments will be necessary to determine whether ARP3 K240R is indeed resistant to ubiquitylation, and whether this impacts the activity of ARP3 in leader cells. ARP3 is a key subunit of the Arp2/3 complex that regulates intracellular actin dynamics in a number of processes, including lamellipodia protrusion during cell motility (Goley and Welch, 2006). Indeed, we observed significantly reduced invasion in parental, leader, and follower cells upon ARP3 knockdown, supporting its importance for cell migration and invasion. Overexpression of Arp2/3 complex subunits, including ARP2, ARP3, ARPC2 and ARPC5, has been shown to promote invasion in multiple cancer types including lung, colorectal, glioblastoma and others (Liu et al., 2013; Zheng et al., 2008; Iwaya et al., 2007; Semba et al., 2006; Kinoshita et al., 2012; Lv et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2013). Our results now further indicate a role for ARP3 as contributing to tumor collective invasion by promoting the leader cell phenotype.

We also investigated the role of the follower cell enriched mutation KDM5B L685W. Surprisingly, overexpression of wild-type KDM5B in leader cells suppressed invasive chains, as well as the ability to lead invasive chains when mixed with followers. By contrast, overexpression of KDM5B L685W supports chain-like invasion. Interestingly, these data are seemingly at odds with published data showing that overexpression of wild-type KDM5B in cancer cells increases their migration and invasion in 2D assays (Tang et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Bamodu et al., 2016; Viré et al., 2014; Kuo et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2015), including in H1299 cells (Shen et al., 2015), and may be a reflection of the differences in the assessment of invasion in 2D, which focuses on the behavior of single cells, and that of cells grown as spheroids and undergoing collective invasion. Collective invasion requires cooperation between cell phenotypes, and the ability of cells in the population to take on distinct roles upon suspension in 3D. One interpretation of our data is that overexpression of wild-type KDM5B suppresses chain-like invasion by suppressing phenotypic plasticity, tipping the balance away from cooperative behavior, and that KDM5B L685W is somehow deficient in this regard. KDM5B acts as a transcriptional repressor, and its sustained expression in leader cells may act to promote phenotypic stability by repressing the follower ‘program’, thus preventing the emergence of the alternative (follower) phenotype. Consistent with this idea, the isolation of cells that take the lead position in 3D invasive streams from the parental favors those that have retained parental levels of KDM5B and lack the mutation, while cells that take the follower position are selectively enriched for mutant KDM5B and exhibit significantly reduced overall KDM5B expression and a skewed intracellular H3K4me2/3-to-H3K4me1 ratio relative to leaders, consistent with reduced/compromised intracellular KDM5 activity. It is also possible that whereas other ‘dominant-acting’ mutations (such as ARP3 and potentially others) directly promote leader behavior, wild-type KDM5B may be a passive participant in the selective outgrowth of leaders. Indeed, wild-type KDM5B expression was not sufficient to drive leader activity in follower cells. Rather, we favor the hypothesis that reduced KDM5B activity and/or expression facilitates population plasticity and cooperative behavior. Interestingly, KDM5B was recently identified as a key suppressor of transcriptomic heterogeneity. Whereas KDM5B overexpression enforces the phenotypic stability of luminal breast cancer cells, its depletion or inhibition has been shown to promote transcriptional plasticity and to facilitate breast cancer cells to overcome therapeutic resistance (Hinohara et al., 2018). Reduced KDM5B expression and/or activity and the ensuing transcriptomic heterogeneity may also be a necessary step for the emergence of the specialized leader and follower phenotypes that define collectively invading chains. In this regard, it is interesting to note that leader cell cultures tend to be phenotypically stable over time and retain their highly invasive phenotype, whereas follower cultures exhibit a greater degree of phenotypic plasticity, with a tendency to spin off new invasive chains (and hence take on leader characteristics) over time (Konen et al., 2017), suggesting that at least some components of collective behavior are epigenetically driven. At least in some cases, knockdown of KDM5B in H1299 parental cells (but not isolated leaders or followers) promotes an increase in chain number and invasive area (Fig. S4).

Previous studies have suggested that cooperation between phenotypically and genetically distinct subpopulations derived from a common tumor cell population are necessary to promote invasion and/or metastasis in vivo. For example, Calbo et al. (Calbo et al., 2011) found that neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine-like clones derived from a common primary murine SCLC tumor were incapable of completing metastasis on their own, but once re-mixed became highly metastatic. Shared copy number variations confirmed a common clonal origin, but some genetic alterations (e.g. amplification of Mycl1) were only observed in the neuroendocrine-like population. Likewise, Mateo et al. (Mateo et al., 2014) found that co-culture of phenotypically distinct subpopulations isolated from the PC-3 prostate cancer cell line promoted invasion and metastasis over either population in isolation. Other studies have shown that the post-hoc mixing of cells engineered to undergo EMT or to express activated HRAS with the non-engineered control population was necessary to fully complete metastasis (Tsuji et al., 2008) or to promote collective motility of breast epithelial cells (Liu et al., 2012). The necessity for heterogeneity in the transcriptional program, even when genetically driven, is an emerging theme, and is consistent with our observations here.

Emerging research regarding how followers cooperate with leaders to promote their invasive capabilities center on concepts such as contact inhibition of locomotion (CIL) and movement along a chemical gradient (Mayor and Etienne-Manneville, 2016; Jolly et al., 2018). CIL occurs when a migrating cell contacts another cell and begins forming protrusions opposite the site of contact to move in the opposite direction (Abercrombie, 1970; Abercrombie and Heaysman, 1953; Mayor and Carmona-Fontaine, 2010). In this case, follower cells contact leader cells, forcing them to polarize and move in a forward direction. Follower cells also regulate signaling to leader cells, often through creation of chemical gradients that motivate leader cells to move in a particular direction (Mayor and Etienne-Manneville, 2016; Theveneau et al., 2010; Malet-Engra et al., 2015; Valentin et al., 2007; Dona et al., 2013; Muinonen-Martin et al., 2014). Indeed, we previously discovered that follower and leader cells engage in a symbiotic relationship, in which follower cells promote the survival and proliferation of leader cells, which in turn secrete VEGFA to promote the motility of follower cells (Konen et al., 2017).

Our sequencing data and the ability to discern the clonality of the distinct leader and follower subpopulations, relative to that of the parental population from which they were derived, allows us to construct a model of the population origins (Fig. 6C). In a population of tumor cells that are already functionally triploid, ACTR3 and KDM5B undergo mutation, each in separate cells. These mutational events are the beginning of the divergent paths that will develop two separate but cooperative subpopulations. Cells containing mutant ACTR3 go on to form the highly invasive, slow-proliferating leader cells, while cells containing the KDM5B mutation ultimately become the follower population of invasion-deficient rapidly proliferating cells. Expressing the leader-specific ACTR3 mutation in follower cells increases chain-like invasion. Likewise, expressing the follower-specific KDM5B mutation in leader cells increases chain-like invasion. Our phenotypic data adds to this model the necessity for cells exhibiting both the leader phenotype and a follower phenotype to the cooperative behavior demonstrated in collective invasion.

The approach used herein, while innovative, does have certain limitations. First, the work focuses on the characterization of leader and followers isolated from a single NSCLC-derived cell line. How universal the identified mutations/genes might be in contributing to leader/follower behavior in other cell lines or cancer types is currently unknown. In addition, while our functional characterization supports a potential role for ACTR3 and KDM5B in modulating collective invasion in this setting, these were only two of the phenotype-selective mutations identified. It is possible that no single alteration in isolation is sufficient to fully drive either phenotype, but rather the combinatorial effects of multiple genetic and epigenetic alterations contribute to collective behavior. Studies aimed at similar analyses of multiple cell lines, or collective invasion models and across cancer types may converge on critical ‘drivers’ or pathways. Ultimately the identification of such key alterations may help in clinical decision-making by identifying predictive biomarkers or new therapeutic targets. Indeed, several molecular inhibitors of the KDM5 family are currently under development, particularly in the setting of combination therapy and therapy resistance (Horton et al., 2016a,b; Vazquez-Rodriguez et al., 2018; Nie et al., 2018; Vinogradova et al., 2016; Johansson et al., 2016; Tumber et al., 2017; Bayo et al., 2018). Chemical inhibition of KDM5B as an anti-metastatic modality has not yet been tested. Moreover, a recently discovered Arp2/3 inhibitor CK-666 (Nolen et al., 2009) has been shown to inhibit cell motility in vivo (Ilatovskaya et al., 2013). An alternative approach would be targeting other components of the Arp2/3 pathway. One such target, PLK4, has been implicated as a driver of cancer invasion and metastasis in part through its interaction with Arp2/3 subunits (Kazazian et al., 2017), and PLK4 inhibitors are currently under clinical investigation for patients with advanced solid tumors. Our identification of a panel of mutations delineating leader and follower cell phenotypes in a non-small cell lung cancer tumor population is an initial step towards elucidation of how heterogeneous genetic mutations contribute to cancer metastasis and how these vulnerabilities can be exploited to circumvent the development of metastasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and transfections

Leader and follower cells isolated via the SaGA technique from the H1299 human NSCLC cell line (Konen et al., 2017), as well as the parental H1299 cell line (ATCC, Manassas, VA), were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 units ml−1 of penicillin-streptomycin and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. H1299 cells were mycoplasma tested and authenticated using SNP analysis through the Emory Genomics Core as previously described (Konen et al., 2017). H1299 cells had been transfected with the Dendra2 as previously described (Konen et al., 2017). HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 units ml−1 of penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2.

For ARP3 lines, lentivirus was prepared by seeding 2×106 HEK293T cells in a 100 cm dish and co-transfecting with 5 µg transfer vector, 0.5 µg pMD2.G (Addgene plasmid #12259), 5 µg psPAX2 (Addgene plasmid #12260), and 1 µg of lentiviral vector. After 24 h, medium was replaced with 5 ml fresh complete medium, then virus-containing medium was collected after 24 h. Medium was centrifuged for 3 min at 200 g, 4°C, and then supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 µm low protein-binding filter.

Target cells were seeded at 70% confluence in a six-well plate one day prior to lentivirus collection. After virus collection, target cell media was replaced with 1 ml complete medium plus 340 µl virus stock and 1.34 µl polybrene (10 mg ml−1 stock), added dropwise. After 24 h, medium was replaced with 2 ml complete medium. Selection antibiotics (shRNA: puromycin; ARP3 expression vectors: hygromycin) were added 48 h after viral infection.

shACTR3 constructs were obtained from Millipore Sigma TRCN0000029383 and TRCN0000380403. mCherry-ARP3 lentiviral constructs were created by cloning ARP3-pmCherryC1 [Addgene plasmid #27682, deposited by Christien Merrifield (Taylor et al., 2011)] into the pCDH-UBC-MCS-EF1 Hygro backbone. The UBC promoter was subsequently exchanged for a CMV promoter. The ARP3 K240R mutation was created using site-directed mutagenesis.

The HA-KDM5B, pLKO-scrambled, pLKO-KDM5Bsh1 and pLKO-KDM5Bsh2 constructs were a kind gift from Dr Qin Yan (Department of Pathology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT) (Sayegh et al., 2013). The puromycin selection marker was exchanged for a hygromycin cassette, and the KDM5B L685W mutation was introduced by site-directed mutagenesis. H1299 cells were transfected with 2 µg plasmid vector to 105 cells per well of a six-well plate with Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After 48 h, transduced cells were selected with 500 µg ml−1 hygromycin.

Lentivirus was prepared by seeding 9×105 HEK293T cells in a 6 cm dish and co-transfecting with 0.1 µg VSV.G (viral envelope plasmid), 0.9 µg dR8.2 (viral packaging plasmid) and 1 µg of lentiviral vector at 24 h post-seeding. After an additional 24 h, medium was replaced with 6 ml fresh complete medium, then virus-containing medium was collected after a further 24 h. Medium was centrifuged for 3 min at 200 g, 4°C, and then supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 µm low protein-binding filter. Target cells (H1299 parental, leader and follower cell lines) were seeded at 105 cells per well in a six-well plate. Target cells were infected the next day by overlay with 1 ml complete medium plus 300 µl viral stock and 10 µg ml−1 polybrene. After 24 h, medium was replaced with 2 ml complete medium. Cells were selected with 3 µg ml−1 puromycin at 48 h after viral infection.

RNA-seq and variant calling

RNA-seq was performed in triplicate on H1299 parental, leader and follower cells. For parental cells, three different passages were used. For follower cells, three separately isolated populations were used. For leader cells, two separately isolated populations were used: one passage of one population, and two passages of the other. RNA library preparation and sequencing were carried out by the Emory Integrated Genomics core and Omega Bio-Tek, Inc. using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA kit, followed by quantification using a Quantus Fluoremeter (Promega) and integrity assessment using an Agilent 2200 Tapestation instrument. Sequencing was performed using a HiSeq2500 instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA), with 50 million total sequencing reads generated per sample using the PE100 run format.

Data processing and statistical analyses were performed by the Emory Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource. Raw paired-end fastq reads were assessed for quality and contamination using FastQC (Andrews, 2010) and trimmed with Trimmomatic v0.32 (Bolger et al., 2014). Quality-filtered reads were mapped against human reference genome hg19 using STAR aligner v2.3.0 (Dobin et al., 2012). Picard tools v1.111 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard) was used to assess post-alignment quality control and to remove PCR duplicates. With an average yield of 30 million post-filtered reads, 88% of the reads mapped uniquely with 78% of reads covered in the coding and UTR region. Genomic variants from RNA-seq were called using SamTools v0.1.19 mpileup (Li et al., 2009) with Varscan v2.3.6 (Koboldt et al., 2012) and functionally annotated using ANNOVAR (Wang et al., 2010). A filtering criterion was applied requiring that each reported variant had ≥6× depth of coverage, with more than two supporting alternate reads in all samples. Variants associated with intronic, intergenic or synonymous changes, pseudogenes, non-coding RNAs or sex chromosomes were excluded. Variants were filtered if they were known in dbSNP v137 (Sherry et al., 2001) but not present in COSMIC v67 database (Tate et al., 2019). This resulted in a total of 6240 variants. A pairwise two-sided independent t-test was done to compare cell populations mean variant allele frequencies between the groups. RNA-seq data generated as part of this project have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession #PRJNA542374 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA542374).

Western blotting

Total cellular protein expression was assessed via western blotting as previously described (Konen et al., 2016). For histone detection, trypsinized cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed with Triton X-100 extract buffer [PBS containing 0.5% Triton X 100, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 0.02% sodium azide] for 10 min on ice. Samples were collected by centrifugation for at 4°C for 10 min at 500 g. Histones were then acid extracted in 0.2 M HCl by rotation overnight at 4°C. Samples were then electrophoresed on a 6.5% SDS-PAGE gel and subject to western blotting.

Reagents and antibodies

Primary antibodies for western blot: ARP3 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, cat. no. sc-48344 – immunogen: residues 1–110 of human ARP3) was used at 1:1000. KDM5B antibody (Sigma, cat. no. HPA 027179 – immunogen: residues 1401–1481 of human KDM5B) was used at 1:500. GAPDH antibody (Cell Signaling, cat. no. 2118) was used at 1:30,000. Anti-β-tubulin antibody was used (Sigma, cat. no. T4026) at 1:5000. Anti-HA antibody (Biolegend cat. no. 901501) was used at 1:1000. Anti-H3K4me3 and -H3K4me2 antibodies (Millipore cat. nos 07-473 and 07-030, respectively) were used at 1:10,000. Anti-H3K4me1 antibody (Cell Signaling cat. no. 5326T) was used at 1:5000. Anti-H4 antibody (Millipore cat. no. 05-858R) was used at 1:20,000. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used at 1:10,000 for western blotting.

3D invasion assays, spheroid microscopy and image analysis

Spheroids were generated as previously described (Konen et al., 2016) and embedded in 2 mg ml−1 Matrigel (BD Biosciences) diluted in complete medium. Images were taken at 0 h, 24 h and, in some cases, 48 h post-embedding at 4× using either an Olympus IX51 or CKX41 microscope.

For mixed spheroid experiments, cells were plated together in low-adhesion wells in the indicated ratios with 3000 total cells per spheroid and embedded as previously described. After 24 h, spheroids were imaged using a Leica SP8 inverted confocal microscope. Invasive area and spheroid circularity were measured using ImageJ as previously described (Konen et al., 2017).

Target validation

DNA and RNA were isolated from H1299 parental, leader and follower cells using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit and the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), respectively. Isolation of samples occurred in two independent biological replicates. RNA was reverse transcribed with M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to generate cDNA. Primers were designed and used to amplify regions surrounding each locus of interest subject to Sanger sequencing at GENEWIZ (South Plainfield, NJ). Primer sequences are listed in Table S1. PCR products were cloned into the pCR4-TOPO TA vector by TOPO-TA cloning (Thermo Fisher Scientific 450071, Carlsbad, CA) and transformed into bacteria. Fifty individual colonies for each gene in each cell type were re-streaked on a new ampicillin plate, and 20 colonies each sent to GENEWIZ for Sanger sequencing.

Cell proliferation assay

H1299 cells expressing constructs for either overexpression or knockdown of KDM5B or ARP3 were seeded at 103 cells per well in six wells each of a 96-well plate. After 24–120 h growth, cells were fixed with 100 µl per well cold 10% trichloroacetic acid for 1 h at 4°C, washed three times in water and air dried. Cells were then stained with 100 µl 0.4% sulforhodamine B in 1% acetic acid for 30 min, washed three times in 1% acetic acid and dried. Dye was reconstituted in 200 µl 10 mM Tris-HCl base (pH 10.5) for 30 min. Optical density (OD) at 510 nm was measured, and the fold-change in OD determined as: (ODX hours)/(OD24 hours).

Targeted deep resequencing and analysis

The targeted region of KDM5B surrounding exon 15 was PCR amplified using primer sequences listed in Table S1. Amplified products were purified with SPRI beads (KAPA Biosystems, Cape Town, South Africa). Libraries were then created with custom TruSeq compatible adapters and KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (KAPA Biosystems, Cape Town, South Africa). Quality for each library was checked using an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA) using 150 bp paired-end sequencing at NYU Genome Technology Center. Quality trimmed reads were mapped to the human genome (GRCh37) using Bowtie 2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). Variant allele frequencies for the KDM5B SNP (rs1141108) and the linked KDM5B L685W mutation were quantified as the fraction of reads (average depth=348,327 reads per line) exhibiting the A or G allele at position chr1: 202715284 or the A or C variant at position chr1:202715414 using R packages Rsamtools, ShortRead, GenomicAlignments and BSgenome.Hsapiens.UCSC.hg19 (Lawrence et al., 2013; Morgan et al., 2009; 2017; R Core Team, 2017; The Bioconductor Dev Team, 2014). Differences in KDM5B variant allele frequencies were based on analysis of variance with Tukey's post-hoc correction using the R functions ‘aov’ and ‘TukeyHSD’, respectively.

Histone demethylase activity assay

For direct quantification of H3K4me3 demethylase activity, cells were lysed by sonication in PBS (three times for 4 s) in the presence of protease inhibitors. Equal amounts of protein were incubated with a histone H3K4me3 substrate for 2 h at 37°C before specific immunodetection of the H3K4me2 product using Epigenase™ JARID demethylase activity/inhibition assay kit (Epigentek P-3083, Farmingdale, NY). Detailed reaction conditions were as previously described (Wang et al., 2013; Dalvi et al., 2017).

Statistical analysis

A two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test was used to assess statistical significance between any two conditions. Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test was used for experiments in which three or more conditions were being compared. The c.i. of proportions in the mixed spheroid experiments were calculated via the Wilson–Brown method. Fisher's exact test was used to test the association of the identified mutations and the phenotypes (e.g. mutant versus wild-type, leader versus follower) in TOPO-TA cloning experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr Qin Yan (Yale University) for the KDM5B expression constructs, and Dr Zhengjia (Nelson) Chen (Emory Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource) for his assistance with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: E.L.Z., B.P., J. Konen, X.C., E.D.M., M.P.T., A.I.M., P.M.V.; Methodology: E.L.Z., B.P., J. Konen, N.S., M.P.T.; Software: B.D., M.R., N.S., J.R.H., C.Z., B.G.B., X.C., M.P.T., J. Kowalski; Formal analysis: E.L.Z., B.P., B.D., M.R., N.S., L.W., C.Z., B.G.B., E.D.M., J. Kowalski; Investigation: E.L.Z., B.P., J. Konen, B.D., M.R., N.S., L.W., J.R.H., C.Z., B.G.B.; Resources: X.C.; Data curation: B.D., M.R., J. Kowalski; Writing - original draft: E.L.Z., B.P.; Writing - review & editing: E.L.Z., B.P., J. Konen, B.D., M.R., N.S., L.W., J.R.H., C.Z., B.G.B., X.C., E.D.M., M.P.T., J. Kowalski, A.I.M., P.M.V.; Visualization: E.L.Z., B.P., N.S., L.W., J.R.H.; Supervision: X.C., E.D.M., M.P.T., J. Kowalski, A.I.M., P.M.V.; Project administration: E.L.Z., B.P., A.I.M., P.M.V.; Funding acquisition: E.L.Z., B.P., A.I.M., P.M.V.

Funding

This project has been funded in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants 2R01CA077337 (to P.M.V.), R01CA201340-01 and 1U54CA209992 (to A.I.M.), R01GM117400 (to M.P.T.), R01GM114306 (to J.R.H. and X.C.) and SPORE grant P50CA70907 (to E.D.M). Additional support was provided to M.P.T. by the Georgia Clinical & Translational Science Alliance of the National Institutes of Health under award number UL1TR002378, to E.D.M (RP160493) and J.R.H. and X.C. (RR160029) by the CPRIT Program, and to E.D.M. by The Welch Foundation (I-1878). E.L.Z. was supported by NIH Predoctoral Fellowship 1F31CA186511. B.P. was support by NIH Predoctoral Fellowship 1F31CA225049. B.G.B. was supported by postdoctoral fellowship PF-17-109-1-TBG from the American Cancer Society. Support of the Emory Integrated Genomics Core Shared Resource, the Emory University Integrated Cellular Imaging Microscopy Core, and the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource is provided by the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University core grant under award number 2P30CA138292. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Data availability

RNA-seq data generated as part of this project have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession #PRJNA542374.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.231514.supplemental

References

- Abercrombie M. (1970). Contact inhibition in tissue culture. In Vitro 6, 128-142. 10.1007/BF02616114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abercrombie M. and Heaysman J. E. M. (1953). Observations on the social behaviour of cells in tissue culture: I. Speed of movement of chick heart fibroblasts in relation to their mutual contacts. Exp. Cell Res. 5, 111-131. 10.1016/0014-4827(53)90098-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander S., Koehl G. E., Hirschberg M., Geissler E. K. and Friedl P. (2008). Dynamic imaging of cancer growth and invasion: a modified skin-fold chamber model. Histochem. Cell Biol. 130, 1147-1154. 10.1007/s00418-008-0529-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander S., Weigelin B., Winkler F. and Friedl P. (2013). Preclinical intravital microscopy of the tumour-stroma interface: invasion, metastasis, and therapy response. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 25, 659-671. 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S. (2010). FastQC: A Quality Control tool for High Throughput Sequence Data.

- Bamodu O. A., Huang W. C., Lee W. H., Wu A., Wang L. S., Hsiao M., Yeh C. T. and Chao T. Y. (2016). Aberrant KDM5B expression promotes aggressive breast cancer through MALAT1 overexpression and downregulation of hsa-miR-448. BMC Cancer. 10.1186/s12885-016-2108-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayo J., Tran T. A., Wang L., Peña-Llopis S., Das A. K. and Martinez E. D. (2018). Jumonji inhibitors overcome radioresistance in cancer through changes in H3K4 methylation at double-strand breaks. Cell Rep. 25, 1040-1050.e5. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A. M., Usadel B. and Lohse M. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114-2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronsert P., Enderle-Ammour K., Bader M., Timme S., Kuehs M., Csanadi A., Kayser G., Kohler I., Bausch D., Hoeppner J. et al. (2014). Cancer cell invasion and EMT marker expression: a three-dimensional study of the human cancer-host interface. J. Pathol. 234, 410-422. 10.1002/path.4416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calbo J., Van Montfort E., Proost N., Van Drunen E., Beverloo H. B., Meuwissen R. and Berns A. (2011). A functional role for tumor cell heterogeneity in a mouse model of small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell 19, 244-256. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell P. J., Yachida S., Mudie L. J., Stephens P. J., Pleasance E. D., Stebbings L. A., Morsberger L. A., Latimer C., Mclaren S., Lin M.-L. et al. (2010). The patterns and dynamics of genomic instability in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Nature 467, 1109-1113. 10.1038/nature09460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung K. J., Gabrielson E., Werb Z. and Ewald A. J. (2013). Collective invasion in breast cancer requires a conserved basal epithelial program. Cell 155, 1639-1651. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung K. J., Padmanaban V., Silvestri V., Schipper K., Cohen J. D., Fairchild A. N., Gorin M. A., Verdone J. E., Pienta K. J., Bader J. S. et al. (2016). Polyclonal breast cancer metastases arise from collective dissemination of keratin 14-expressing tumor cell clusters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, E854-E863. 10.1073/pnas.1508541113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalvi M. P., Wang L., Zhong R., Kollipara R. K., Park H., Bayo J., Yenerall P., Zhou Y., Timmons B. C., Rodriguez-Canales J. et al. (2017). Taxane-platin-resistant lung cancers co-develop hypersensitivity to JumonjiC Demethylase inhibitors. Cell Rep. 19, 1669-1684. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin E. C., Mcgranahan N., Mitter R., Salm M., Wedge D. C., Yates L., Jamal-Hanjani M., Shafi S., Murugaesu N., Rowan A. J. et al. (2014). Spatial and temporal diversity in genomic instability processes defines lung cancer evolution. Science 346, 251-256. 10.1126/science.1253462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A., Davis C. A., Zaleski C., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Chaisson M., Batut P., Jha S. and Gingeras T. R. (2012). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15-21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dona E., Barry J. D., Valentin G., Quirin C., Khmelinskii A., Kunze A., Durdu S., Newton L. R., Fernandez-Minan A., Huber W. et al. (2013). Directional tissue migration through a self-generated chemokine gradient. Nature 503, 285-289. 10.1038/nature12635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald A. J., Huebner R. J., Palsdottir H., Lee J. K., Perez M. J., Jorgens D. M., Tauscher A. N., Cheung K. J., Werb Z. and Auer M. (2012). Mammary collective cell migration involves transient loss of epithelial features and individual cell migration within the epithelium. J. Cell Sci. 125, 2638-2654. 10.1242/jcs.096875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler I. J. (2003). The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 453-458. 10.1038/nrc1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P. (2004). Prespecification and plasticity: shifting mechanisms of cell migration. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16, 14-23. 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P. and Gilmour D. (2009). Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 445-457. 10.1038/nrm2720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P. and Wolf K. (2010). Plasticity of cell migration: a multiscale tuning model. J. Cell Biol. 188, 11-19. 10.1083/jcb.200909003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P., Noble P. B., Walton P. A., Laird D. W., Chauvin P. J., Tabah R. J., Black M. and Zanker K. S. (1995). Migration of coordinated cell clusters in mesenchymal and epithelial cancer explants in vitro. Cancer Res. 55, 4557-4560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P., Locker J., Sahai E. and Segall J. E. (2012). Classifying collective cancer cell invasion. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 777-783. 10.1038/ncb2548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlinger M., Rowan A. J., Horswell S., Math M., Larkin J., Endesfelder D., Gronroos E., Martinez P., Matthews N., Stewart A. et al. (2012). Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 883-892. 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert-Ross M., Konen J., Koo J., Shupe J., Robinson B. S., Wiles W. G. T., Huang C., Martin W. D., Behera M., Smith G. H. et al. (2017). Targeting adhesion signaling in KRAS, LKB1 mutant lung adenocarcinoma. JCI Insight 2, e90487 10.1172/jci.insight.90487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goley E. D. and Welch M. D. (2006). The ARP2/3 complex: an actin nucleator comes of age. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 713-726. 10.1038/nrm2026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeger A., Krause M., Wolf K. and Friedl P. (2014). Cell jamming: collective invasion of mesenchymal tumor cells imposed by tissue confinement. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1840, 2386-2395. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeger A., Wolf K., Zegers M. M. and Friedl P. (2015). Collective cell migration: guidance principles and hierarchies. Trends Cell Biol. 25, 556-566. 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M., Xu W., Cheng P., Jin H. and Wang X. (2017). Histone demethylase lysine demethylase 5B in development and cancer. Oncotarget 8, 8980-8991. 10.18632/oncotarget.13858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegerfeldt Y., Tusch M., Bro E.-B. and Friedl P. (2002). Collective cell movement in primary melanoma explants. Cancer Res. 62, 2125-2130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinohara K., Wu H.-J., Vigneau S., Mcdonald T. O., Igarashi K. J., Yamamoto K. N., Madsen T., Fassl A., Egri S. B., Papanastasiou M. et al. (2018). KDM5 histone demethylase activity links cellular transcriptomic heterogeneity to therapeutic resistance. Cancer Cell 34, 939-953.e9. 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton J. R., Engstrom A., Zoeller E. L., Liu X., Shanks J. R., Zhang X., Johns M. A., Vertino P. M., Fu H. and Cheng X. (2016a). Characterization of a linked Jumonji domain of the KDM5/JARID1 family of histone H3 lysine 4 demethylases. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 2631-2646. 10.1074/jbc.M115.698449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton J. R., Liu X., Gale M., Wu L., Shanks J. R., Zhang X., Webber P. J., Bell J. S. K., Kales S. C., Mott B. T. et al. (2016b). Structural basis for KDM5A histone lysine demethylase inhibition by diverse compounds. Cell Chem. Biol. 23, 769-781. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilatovskaya D. V., Chubinskiy-Nadezhdin V., Pavlov T. S., Shuyskiy L. S., Tomilin V., Palygin O., Staruschenko A. and Negulyaev Y. A. (2013). Arp2/3 complex inhibitors adversely affect actin cytoskeleton remodeling in the cultured murine kidney collecting duct M-1 cells. Cell Tissue Res. 354, 783-792. 10.1007/s00441-013-1710-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaya K., Oikawa K., Semba S., Tsuchiya B., Mukai Y., Otsubo T., Nagao T., Izumi M., Kuroda M., Domoto H. et al. (2007). Correlation between liver metastasis of the colocalization of actin-related protein 2 and 3 complex and WAVE2 in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 98, 992-999. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00488.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]