Abstract

Background

Patients' participation in medical decision making is an important aspect of patient‐centred care. However, there is often uncertainty about its applicability and feasibility in non‐Western countries.

Objective

To provide an overview and assessment of interventions that aimed to improve patients' participation in decision making in non‐Western countries.

Method

Ovid Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process, Other Non‐Indexed Citations, without Revisions and Daily Update and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, were searched from respective inception to February 2018. Studies were included if they (a) were randomized controlled trials, before‐and‐after studies and interrupted time series studies; (b) were conducted in non‐Western countries; (c) aimed to improve patients' participation in dyadic decision making; and (d) reported outcomes relevant to patient participation in decision making. Studies were excluded if they included children, were about triadic decision making or solely focused on information provision without reporting outcomes related to patient participation. Narrative synthesis method was used for data analysis and presentation.

Results

A total of 17 studies, 6 RCTs and 11 non‐RCTs, were included across ten countries. Intervention strategies included patient and/or provider communication skills training, decision aids and a question prompt material. Whilst most of the studies reported increased patient participation, those interventions which had provider or patient training in communication skills were found to be more effective.

Conclusion

Interventions to improve patient participation, within the context of dyadic decision making, in non‐Western countries can be feasible and effective if communication skills training is provided for health‐care providers and/or patients.

Keywords: decision making, health communication, patient participation, patient‐centred care, systematic reviews

1. INTRODUCTION

Participation in decision making is a process where engaged patients and health‐care providers partake in shared decision making through the meaningful exchange of information and experiences.1 It is a key characteristic of patient‐centred health care, a paradigm that has become popular in recent decades, replacing more paternalistic health‐care models. Recent evidence shows that greater participation in health‐care decisions increases patients' satisfaction, improves patient‐provider relationships, facilitates medication adherence and decreases health‐care costs.2, 3 There is also emerging evidence that participation in decisions may reduce health inequalities experienced by vulnerable groups such as racial and ethnic minorities, low literacy groups and seniors.4 However, issues such as time constraints, patient characteristics, low health literacy and cultural factors are often reported as barriers to participative decision making, with some saying that it is impractical amongst certain groups.5, 6, 7

Globally, this paradigm shift was reflected in the pronouncement of the Alma‐Ata Declaration in 1979, a landmark moment calling for greater participation from individuals and communities in their health‐care planning and implementation.8, 9 More recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) published the Framework on Integrated People‐Centred Health Services (IPCHS), promoting Universal Health Coverage through equal, responsive, affordable and quality health‐care services.10 An important strategy proposed by this Framework is to engage and empower individuals and families.11 A number of strategies, including shared clinical decision making, were proposed. However, the report fell short of providing recommended strategies, concept analyses and best practices.

In many Western countries, policies have been developed to support patients' participation in health‐care decision making and the use of decision aids, question prompt lists and training for both clinicians and patients.12, 13, 55 For example, in Australia, the statement ‘I have a right to be included in decisions and choices about my care’ is part of the Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights.14 However, less is known about how to effectively involve patients in health‐care decisions in non‐Western countries. In these settings, some have argued that the concepts of ‘patient centeredness’ and ‘active participation’ are based on the Western ideology of individual autonomy and are therefore less applicable.16, 17 In cultures where individuals see themselves as agents of a family, community or a tribe, within a hierarchical community, health‐care professionals are often to be respected.18, 19, 20 Questioning by patients is to be avoided to bring harmony during encounters.18, 19, 20 Other factors that may be prevalent in some non‐Western countries are high patient loads, lack of skills in participatory communication amongst health providers, a lack of relevant research evidence and low health literacy amongst patients.20, 21, 22 These lead to the question of whether patient‐centred care, and more specifically, patients' participation in health decisions, is a feasible and appropriate strategy in non‐Western country contexts. This systematic review aims to identify interventions designed to improve adult patients' participation in health‐care decisions in non‐Western countries, assess their feasibility and synthesize factors that influence their effectiveness.

2. METHODS

This systematic review is reported in accordance with preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses (PRISMA) (Appendix S1).23

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The PICOS (participants, intervention, comparator, outcome and study design) 23 approach was used to define the following eligibility criteria for study selection.

2.1.1. Participants

Studies were included if participants lived in non‐Western countries (defined as countries that are not members of UN classification of Western European and Other States Group (WEOG)).24 The same classification method was used in a previous systematic review 25 We excluded studies that included children (aged <18).

2.1.2. Interventions

We included studies which aimed to improve the participation of patients in the process of decision making. Studies were excluded if interventions: (a) only focused on information provision; (b) were about promoting self‐management of conditions; (c) were about patient participation in triadic decision making; and (d) aimed at promoting participation in clinical trials, patient safety measures or planning and development of health‐care programmes.

2.1.3. Outcomes

Outcomes related to patient activation, patient or provider participatory behaviours during the decision‐making encounters were analysed. Patient activation is a broad concept with a definition of ‘an individual's knowledge, skill, and confidence for managing their health and health care’.26 In this systematic review, we only included studies which reported patient activation outcomes in relation to individuals’ skills and confidence in participating in health‐care decision making.

2.1.4. Study designs

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), controlled or uncontrolled before‐and‐after studies with pre‐ and post‐test data available and interrupted time series studies were included.

2.2. Search strategy and study selection

We systematically searched databases using keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) related to pre‐specified PICOS criteria. Some segments of our search strategy were adapted from other published systematic reviews with similar concepts.4, 27 The search strategy was originally developed in Medline via OvidSP (Appendix S2) and later modified to other databases. We initially limited our search to humans, adults and the English language, and later expanded the search to the non‐English language records. Returned records from database searches were combined, duplicates removed using Endnote X8 software, and remaining references imported to the Covidence tool28 for screening, data extraction and quality assessment purposes. Two reviewers conducted title and abstract screening and full‐text screening of eligible studies on Covidence. Disagreement on the selection of certain studies was resolved by consensus.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

We extracted data using the Covidence online tool28 and an adaptation of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group data extraction template.29 We recorded country of origin, study design, participant numbers, intervention characteristics, theoretical framework, setting/conditions, outcome measures and detailed outcome results.

The quality of RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias).30 The quality of non‐randomized studies was assessed using the modified Downs and Black's checklist,31 rating each study numerically against 27‐item questions, and the total score ranged from 0 to 28.

2.4. Data analysis

Due to the wide variation of study designs, intervention strategies and outcome measures used in the included studies, a narrative synthesis method was used. Narrative synthesis is a process of exploring study characteristics and their relationships within (and between) included studies in order to identify factors influencing the effectiveness and implementation of interventions.32 The process of narrative synthesis was partially guided by recommendations by Popay et al.32 We used textual description, grouping and tabulation methods for preliminary synthesis and exploration of patterns across studies.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

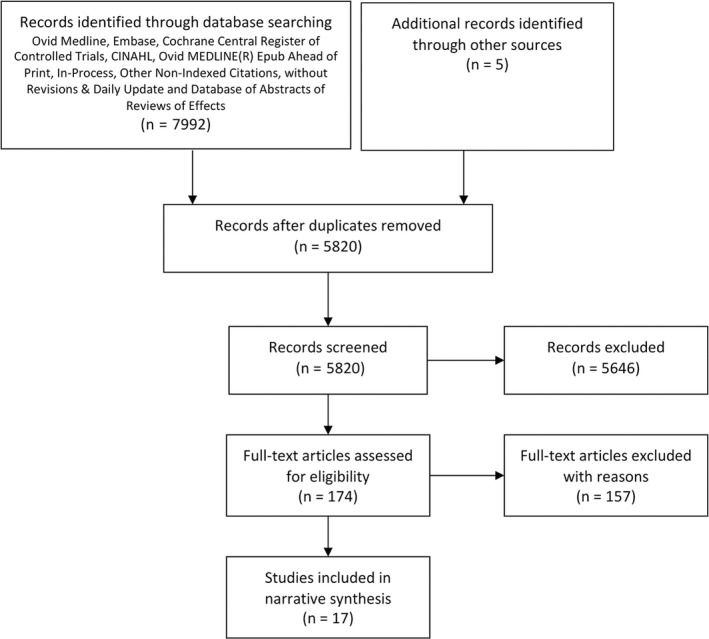

A total of 7992 studies were identified through the initial search of publications in the English language. Two additional studies were added by recalling previously known studies and further three from citation searching. The search for non‐English language papers within the same databases identified 476 studies; however, none of these were eligible for inclusion. Seventeen studies (6 RCTs and 11 non‐RCTs) were included in the final stage of data extraction and quality assessment (Figure 1). The included studies were conducted in 10 countries, including Hong Kong and mainland China (n = 3), Japan (n = 3), South Korea (n = 2), Mexico (n = 2), Nicaragua (n = 1), Iran (n = 1), Indonesia (n = 2), Namibia (n = 1), Trinidad and Tobago (n = 1) and Honduras (n = 1). There were a variety of clinical conditions featured in these studies, including family planning (n = 5), general consultations (n = 3), breast cancer treatment (n = 2), dental consultations, carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), primary open‐angle glaucoma (POAG), birth choice, mental health, HIV antiretroviral treatment and advanced care (see Table 1 and Table 2).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 1.

Summary of intervention strategies used in included studies

| Study | Theoretical framework | Target population | Intervention elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provider communication skills training | |||

| Roter 199833 (Trinidad & Tobago) | Interpersonal communication and counselling (IPC/C) | Ambulatory care doctors |

|

| Brown 200034 (Honduras) | Interpersonal communication and counselling (IPC/C) | Ambulatory care doctors |

|

| Kim 200035 (Indonesia) | Client‐centred care | family planning providers in rural areas |

|

| Kim 200236 (Mexico) | Interpersonal communication and counselling (IPC/C) | Resident doctors working at rural clinics |

|

| Patient communication skills training | |||

| Kim 200337 (Indonesia) | Interpersonal communication and counselling (IPC/C) | Family planning clinics |

|

| Maclachlan 201638 (Namibia) | Social cognitive theory of self‐efficacy (Bandura, 1977) | Hospitals with high HIV patient load |

|

| An 201739 (South Korea) | Nil | Mental hospital |

|

| Patient decision aids (± training) | |||

| Lam 201340 (Hong Kong, China) | International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration criteria | Government‐funded breast centres |

|

| Gong 201741 (South Korea) | IPDAS criteria | Outpatient clinic at a tertiary referral setting |

|

| Osaka 201742 (Japan) | Ottawa Decision Support Framework (ODSF), IPDAS criteria, social comparison theory, social learning theory | Nil |

|

| Kim 200543 (Mexico) | Normative model of client‐provider communication for family planning decision making (unpublished) | Government health facilities |

|

| Kim 200744 (Nicaragua) | Normative model of client‐provider communication for family planning decision making (unpublished) | Government health facilities |

|

| Hu 200845 (China) | nil | Public general dental hospital and individual clinics |

|

| Farrokh‐Eslamlou 201446 (Iran) | WHO DMT tool | Urban and rural public health facilities |

|

| Shum 201747 (Hong Kong, China) | IPDAS criteria | Ophthalmology outpatient clinic |

|

| Torigoe 201648 (Japan) | Ottawa Decision Support Framework (ODSF) | Obstetric institutions that permitted VBAC |

|

| Question prompt material | |||

| Shirai 201249 (Japan) | Social cognitive theory of self‐efficacy (Bandura, 1977) | National Cancer Centre Hospital |

|

Table 2.

Summary of included studies

| Author year | Study design | Country | Relevant outcome measure/s | Number | Outcome | Change in decisional conflict/Preparedness | Patient participatory behaviours | Provider participatory behaviours | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider communication skills training | |||||||||

| Roter 199833 | CBA | Trinidad and Tobago | Interaction analysis of audiotaped clinical encounters using RIAS, patient exit interviews, self‐administered questionnaire for health providers | 18 doctors | Compared to untrained doctors, trained doctors experienced significant improvements in terms of using facilitators in their talk (change score: 3.12 vs −0.89, P = 0.015), using open questions (change score: 2.33 vs −0.35, P = 0.023) and being rated friendlier (change score: 0.75 vs −0.40, P = 0.007). No significant difference in change in medical information giving, medical and lifestyle counselling | ↑ | 19 | ||

| Brown 200034 | CBA | Honduras | Interaction analysis of audiotaped clinical encounters using RIAS, patient exit interviews, self‐administered questionnaire for health providers | 49 health‐care providers, 220 patient consultations pre‐test, 218 post‐test | Compared to untrained doctors, trained doctors talked more (mean scores: 136.6 vs 94.4, P = 0.0001), used more positive talk (15.93 vs 7.99, P = 0.001), less negative talk (0.11 vs 0.59, P = 0.018), more emotional talk (15.7 vs 5.5, P = 0.021), and provided more medical counselling (17.3 vs 11.3, P = 0.026). Patients of trained doctors talked more (mean score: 113.8 vs 79.6, P = 0.011) and disclosed more medical information (54.7 vs 41.7, P = 0.002) | ↑ | ↑ | 16 | |

| Kim 200036 | CBA | Indonesia | Interaction analysis of audiotaped clinical encounters using RIAS, provider interviews, patient exit interviews | 201 providers from 170 clinics | Providers experienced significant increase in their frequency of facilitative communication after the training (from 15 to 30, P < 0.001). Clients of trained doctors experienced significant increase in their frequency of active communication (from 3.3 to 7.0, P < 0.001) and numbers of questions they asked (from 1.6 to 3.3, P < 0.001). Both the providers and clients in the self‐assessment and peer review groups experienced significant improvements in their facilitative communication and active communication, whilst the control group without reinforcement did not experience further improvement | ↑ | ↑ | 13 | |

| Kim 200235 | CBA | Mexico | Interaction analysis of audiotaped clinical encounters using RIAS | 60 doctors and 232 patients | Doctors in the intervention group experienced a 238% increase in their frequency of facilitative communication (from 13.6 to 45.9, P < 0.001), whilst the increase in the control group was 124% (14.6‐32.7, P < 0.001). After controlling for confounds, the increase was only significant in the intervention group but not in the control group. Frequency of patient participatory behaviours during consultations improved significantly from baseline to follow‐up with no significant differences between the intervention (from 2.4 to 12.7, P < 0.001) and control groups (from 2.6 to 13.0, P < 0.01) | ↑ | ↑ | 18 | |

| Patient communication skills training/coaching | |||||||||

| Kim 200338 | Cluster RCT | Indonesia | Interaction analysis of audiotaped clinical encounters using RIAS; exit interviews | 768 women, 384 in the intervention group, 384 in the control group | Compared to the control group, smart patient coaching patients asked significantly more questions (6.3 vs 4.9, P < 0.01) and expressed concerns and opinions (6.7C vs 5.4, P < 0.05). No difference in seeking clarification (1.8 vs 1.5) | ↑ | See Figure 2 | ||

| Maclachlan 201637 | RCT | Namibia | Interaction analysis of audiotaped clinical encounters using RIAS | 589 patients, 299 in the intervention group, 290 in the control group | Doctors of patients in the intervention group scored higher on facilitation and patient activation (adjusted difference in score 1.19, 95% CI 0.39‐1.99, P = 0.004) and gathered more information (adjusted difference in scores 2.96, 95% CI 1.42‐4.50, P = 0.000). Other doctor communication variables were also higher in the intervention group, however not statistically significant. Patients in the intervention group asked more questions (adjusted difference in score 0.48, 95% CI 0.11‐0.85, P = 0.012) | ↑ | ↑ | See Figure 2 | |

| An 201739 | CBA | South Korea | Administration of Self‐Esteem Scale and Problem‐Solving Inventory | 29 in the intervention group, 31 in the control group | Compared to the control group, the intervention group achieved significantly more positive changes in self‐esteem (mean change ± SD: 4.06 ± 4.42 vs − 1.06 ± 3.66, P < 0.001) and problem‐solving (mean change ± SD: 17.31 ± 19.55 vs −0.54 ± 7.47, P < 0.001) | ↑ | 21 | ||

| Patient decision aid (±training) | |||||||||

| Lam 201342 | RCT | Hong Kong, China | Decision Conflict Scale; Videotape analysis using OPTION scale | 138 women in the intervention group; 138 women in the control group | There was no significant difference in shared decision‐making OPTION scores of providers between the decision aid group and the control group (mean = 33.01, SD = 9.71 vs mean = 32.06, SD = 0.45). The decision aid group had significantly less decisional conflict at one‐week post‐intervention than the control group (mean = 15.8, SD = 15.5 vs mean = 19.9, SD = 16.3, P = 0.016). There was no difference in decision‐making difficulties between the intervention and control groups (17.5 vs 19.2, P = 0.064) | ↑ | ↔ | See Figure 2 | |

| Gong 201748 | RCT | South Korea | Decisional Conflict Scale | 40 in the intervention group, 40 in the control group | There was no significant difference in decisional conflict scores between the intervention and control groups (22 vs 23, P = 0.76). The intervention group had significantly better knowledge than the treatment group (P = 0.04) | ↔ | See Figure 2 | ||

| Osaka 201743 | RCT | Japan | Decisional Conflict Scale | 210 women | Before the surgery and after the intervention, there was no significant difference in total decisional conflict scores between the decision aid, decision aid with narratives and control group (28.7 vs 29.8 vs 31.7). At 1 month post‐surgery, both the decision aid groups had significantly lower decisional conflict scores than the control group (26.5 vs 26.9 vs 32.1) | ↑↔ | See Figure 2 | ||

| Kim 200540 | UCBA | Mexico | Interaction analysis of videotaped clinical encounters using Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS); Assessment of decision‐making process using adapted OPTION tool | 13 providers; 35 consultations at baseline and 45 consultations post‐intervention | There were significant improvements (P < 0.001) in the numbers of sessions where minimum desired level of participatory behaviours by both the clients and providers were met after the intervention. For providers, significant changes in behaviours included the following: validating client preference (73.3% vs 0%), checking clients’ understandings (75.6% vs 0%) and discussing patient participation in decision (37.8% vs 0%). For clients, changes included acknowledging right to choose (40.0% vs 0%), deliberating preference (57.8% vs 0%) and seeking clarifications (68.9% vs 0%). Providers’ overall decision‐making score increased from 19 at baseline to 32 post‐intervention. Clients’ overall decision‐making score increased from 20 to 34 post‐intervention | ↑ | ↑ | 14 | |

| Kim 200741 | UCBA | Nicaragua | Assessment of decision‐making process using adapted OPTION tool; Assessment of quality of consultations and key issues being discussed using client‐provider interaction (CPI) checklist | 59 providers; 426 family planning clients | For new clients, providers’ overall decision‐making score increased significantly from 28.6 at baseline to 36.8 post‐intervention (P < 0.001). For continuing clients, providers’ overall score increased from 24.1 to 27.3 (P < 0.01). Both new and continuing clients experienced significant improvements in their own overall decision‐making scores (new clients: from 22.5 to 27.6, P < 0.001; continuing clients: from 18.1 to 19.9, P < 0.01). The intervention had greater impact on overall decision‐making performances of both providers and clients on sessions involving new clients compared to continuing clients | ↑ | ↑ | 12 | |

| Hu 200847 | UCBA | China | Questionnaires assessing patient satisfaction, comprehension and perceptions | 179 patients | Participants were more likely to rate themselves having participated in decision making after the intervention (OR 5.938, 95%, CI 2.741‐12.865) and at their second visit (OR 2.601, 95% CI 1.205‐5.614) compared to baseline | ↑ | ↑ | 15 | |

| Farrokh‐Eslamlou 201444 | UCBA | Iran | Observation of consultations; exit interviews | 448 clients at baseline and 547 clients post‐intervention | There were significant increases (P < 0.05) in the proportion of sessions where sufficient level of provider participatory behaviours were observed. These included significant increase in giving information about methods (from 58% to 80%), method efficacy (from 54% to 88%), how to use the chosen method (from 81% to 98%) and complication of the chosen method (from 67% to 94%). There were also significant increases in behaviours such as engaging clients to speak (from 75% to 93%) and answering all the client questions (from 89% to 99%) | ↑ | 17 | ||

| Shum 201745 | UCBA | Hong Kong, China | Decisional Conflict Scale | 65 patients | There was significant reduction in decisional conflict after receiving the decision aid tool compared to baseline (mean decisional conflict score 34.3 ± 20.3 vs 48.9 ± 20.4, P < 0.01). | ↑ | 16 | ||

| Torigoe 201846 | UCBA | Japan | Modified Decisional Conflict Scale | 33 women | There was significant reduction in decisional conflict after the decision support intervention compared to baseline (mean decisional conflict score: 2.18 ± 0.36 vs 2.54 ± 0.49, P < 0.001) | ↑ | 17 | ||

| Question prompt materials | |||||||||

| Shirai 201249 | RCT | Japan | Patient satisfaction with the consultation was assessed using five items adapted from a previous study. The number and contents of the questions were measured using interview method immediately after the consultation | 32 cancer patients in the intervention and 31 in the control group | There was no difference between the Question Prompt Sheet (QPS) group and the Hospital Induction Sheet (HIS) group in terms of percentages of patients reporting had asked question (s) (63% vs 71%), numbers (both: median = 1, interquartile range = 2) and types of questions been asked and satisfaction with the consultation, such as satisfaction with asking questions (mean: 6.8 vs 7.8, P = 0.177). The QPS group rated the usefulness of the material in helping them asking questions significantly higher than the Hospital Induction Sheet (HIS) group (4.4 ± 3.6 vs 2.7 ± 2.8, P = 0.003) | ↑ | ↔ | See Figure 2 | |

Abbreviations: CBA: controlled before‐and‐after studies; CI: confidence intervals; N: total number; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RIAS: Roter interaction analysis system; RR: relative risk; SD: standard deviation; UCBA: uncontrolled before‐and‐after or time series studies; empty cells indicate that the outcome was not assessed; ↑ positive effect; ↔ no effect/difference.

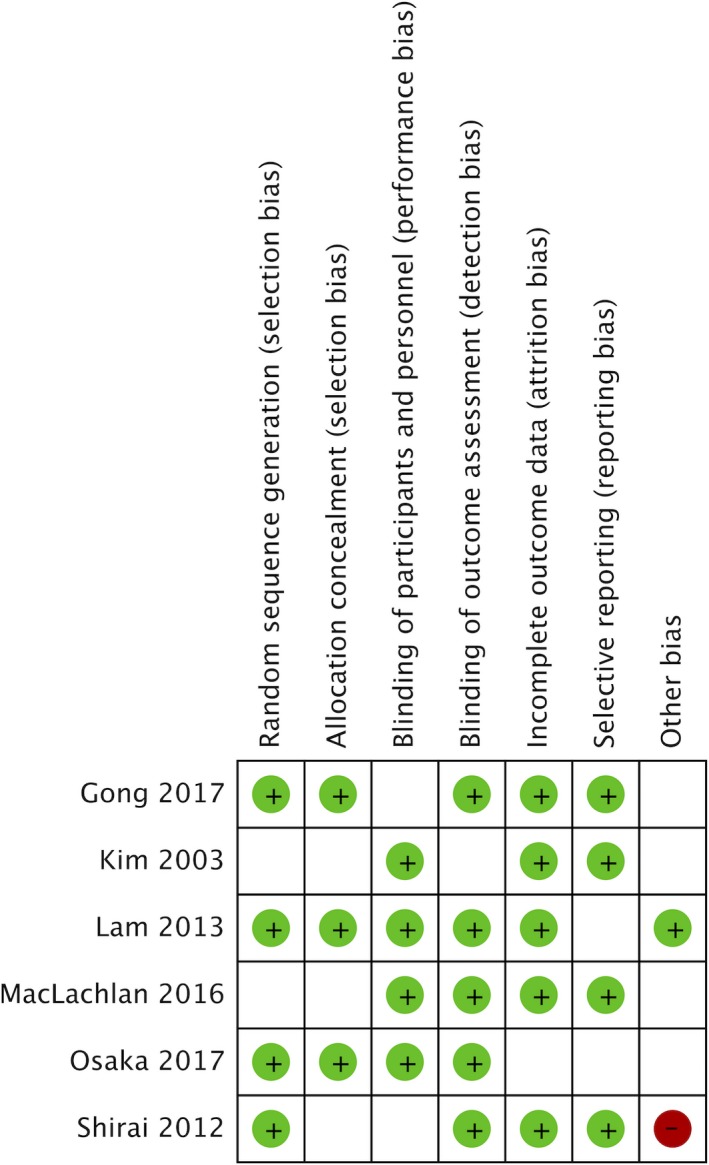

The methodological quality of the included RCTs varied across studies (Figure 2). Two (2/6) did not provide sufficient information on random sequence generation methods, and three (3/6) studies did not describe or have allocation concealment. Blinding of participants and personnel was lacking in two (2/6) studies, and in one study, outcome assessment was not reported in detail to permit a judgement. The Downs and Black quality scores for non‐randomized studies ranged from 12 to 21 (see Table 2).

Figure 2.

RCT studies rated against the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool 59. Green cells indicate low risk; red cells indicate high risk; blank cells indicate unclear risk

3.2. Data synthesis

There were four types of intervention strategies in the included studies; provider communication skills training (n = 4), patient communication skills training (n = 3), question prompt material (n = 1) and patient decision aids (n = 9). Details of elements of each intervention strategies, theoretical background and development processes are summarized in Table 1. Based on our pre‐defined outcome inclusion criteria and emergent patterns in the extracted data, we categorized study outcomes into three groups: (a) change in decisional conflict or preparedness; (b) patient participatory behaviours; and (c) provider participatory behaviours (see Table 2).

3.2.1. Provider communication skills training

Four studies used the conceptual framework of Interpersonal Communication and Counselling (IPC/C) 33, 34, 35 or client‐centred counselling36 for provider communication skills training, and all four were controlled before‐and‐after studies. Two studies33, 34 measured the effects of stand‐alone provider interpersonal communication skills training, whilst the other two35, 36 assessed the impact of self‐assessment, peer review and supervision on the maintenance of provider communication skills. They all used interaction analysis of audiotaped clinical encounters using the Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS). All four studies reported significant improvements in trained doctors’ facilitative talking behaviours, such as using open‐ended questions,33 facilitators (checking for understanding and asking for opinions),33, 34, 35 emotional talk33, 34 and partnership building35, 36 when compared with doctors in the control groups. Improvements in patient active communication, such as asking questions36 and providing medical information,33, 34 were also reported.

3.2.2. Patient communication skills training

Three studies provided communication training for patients. One RCT from Namibia used a curriculum with three components: learning to speak to providers, using tools to help communication and overcoming barriers to communication.37 The second cluster‐randomized study from Indonesia provided individual coaching to patients on asking questions, requesting clarification and expressing concerns prior to their consultations.38 Finally, a controlled before‐and‐after study from South Korea developed a shared decision‐making training programme for people with schizophrenia.39

The Namibian training programme for patients resulted in the doctors of trained participants performing significantly better in facilitating (adjusted difference in score 1.19, P = 0.004) and gathering information (adjusted difference in scores 2.96, P = 0.000) than control group doctors. These trained patients also asked significantly more questions during consultations (adjusted difference in score 0.48, P = 0.012).37 The Indonesian study of individual coaching for patients also resulted in the coached patients asking significantly more questions than those in the control group (6.3 vs 4.9, P < 0.01).38 Similarly, the shared decision‐making training in South Korea found a significant positive change in self‐esteem in the intervention group compared to control (mean change ± SD: 4.06 ± 4.42 vs −1.06 ± 3.66, P < 0.001) which could be seen as empowerment in decision making.39

3.2.3. Decision aids

Patient decision aids (PDAs) were utilized in nine of the 17 included studies and the PDAs were either paper‐based40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 or computer‐delivered.47, 48 Five of these studies (5/9), all from East Asian countries, used the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration checklist to guide the development of their decision aids.42, 43, 45, 46, 48 Of the nine included studies of PDAs, three were RCTs.42, 43, 48 We note that none of the RCTs42, 43, 48 included training as part of their intervention and that the studies which did were all of a weaker study design as uncontrolled before‐and‐after studies (n = 6).40, 41, 44, 45, 46, 47 Nevertheless, amongst these nine studies evaluating patient decision aids, there was a consistent improvement in the patient and provider participatory behaviours in those studies which included provider and/or patient training as part of the intervention.40, 41, 44, 45, 46, 47

The Hong Kong RCT found that the decision aid tool significantly reduced decisional conflict compared with a standard information booklet at one‐week post‐intervention (mean = 15.8, SD = 15.5 vs mean = 19.9, SD = 16.3, P = 0.016). However, there was no difference in providers' participatory behaviours, as analysed on consultation videotapes (mean = 33.01, SD = 9.71 vs mean = 32.06, SD = 0.45). The RCT from Japan found that decisional conflict was significantly reduced for both the decision aid groups one month after receiving them and after having the selected surgery (26.5 vs 26.9 vs 32.1), but not immediately after the intervention and before the surgery (28.7 vs 29.8 vs 31.7).43 Conversely, the RCT study from South Korea 48 which assessed a PDA for carpal tunnel syndrome did not find any difference in the decisional conflict between the PDA (video format) group and the regular information group (control) (22 vs 23, P = 0.76).

Amongst the remaining six uncontrolled before‐and‐after studies, three studies using the WHO family planning decision‐making tool (DMT) reported positive changes in provider and client participatory behaviours (see Table 2).40, 41, 44 The other two studies from China (PDA in POAG) and Japan (PDA in birth choices) reported a reduction in decisional conflict after patients were given PDAs with a short briefing45 and decisional support.46 The study from mainland China, using a 3D multimedia system able to display relevant dental anatomy as an aid for patient‐provider communication, reported that patients felt more involved in decision making, understood decisions and treatment planning.47

3.2.4. Question prompt materials

One study (an RCT) in Japan compared the use of a Question Prompt Sheet (QPS) and standard Hospital Introduction Sheet (HIS) for advanced cancer patients.49 Participants who received the QPS were more likely to find the materials useful in helping them asking questions compared to the HIS group (4.4 ± 3.6 vs 2.7 ± 2.8, P = 0.003); however, there were no differences in asking questions (63% vs 71%) nor total questions asked (both median 1) between these two groups.49

4. DISCUSSION

This systematic review used a narrative synthesis method to summarize the effects of interventions for improving patient participation in health‐care decisions within non‐Western countries. Seventeen studies from 10 countries were included, covering a variety of health topics. These studies evaluated four main strategies, including patient or/and provider communication skills training, PDAs and question prompt material. We summarized the impact of these studies on three outcomes, namely patient decisional conflict, patient participatory behaviours and provider participatory behaviours.

Our findings show an evolution of patient participation research in non‐Western countries over the past two decades which parallels, but is less developed than in Western countries. For example, the earliest studies (Trinidad and Tobago 199833; Honduras 200034; Indonesia 200036; Mexico 200235) focused on training for health‐care providers in communication and counselling skills. These were funded by USAID, and two of these 33, 34 were part of a Quality Assurance Project replicating research from high‐income countries.50 Stand‐alone provider training based on IPC was found to be effective when characterized by two‐way communication, partnership, a caring environment and bridging the social distance.33, 34, 50 These findings were further validated by Kim and her colleagues, who incorporated ongoing supervision and self‐assessment of provider communication skills with the Interpersonal Communication and Counselling (IPC/C) training in Indonesia and Mexico and achieved long‐term maintenance of provider communication skills.35, 36 They suggested that incorporating specific supervision on provider IPC/C skills to the already existing functional provider performance supervision system could be a cost‐effective option in developing countries.35, 36

Communication skills training was evaluated amongst Indonesian patients of providers who had previously received client‐centred counselling skills training.36, 38 Patients received individual coaching which increased their participatory communication behaviours and confirmed the importance of explicit permission or endorsement from providers for patients to speak up and ask questions.38 This supports the notion that patient coaching could complement provider communication skills training in strengthening the partnership relationship during medical consultations.

A patient decision aid, the WHO family planning Decision‐Making Tool (DMT), began to be evaluated next in Mexico (2005),40 Nicaragua (2007)41 and Iran (2014).44 The DMT tool was developed by WHO in 2001 to promote client‐centred counselling and client active participation in decision making.51, 52 It has been translated into 20 languages and utilized by nearly 50 countries.51 These evaluative studies were developed as part of the USAID Information and Knowledge for Optimal Health (INFO) project, which had a mission of disseminating best practices in reproductive health care by facilitating knowledge sharing.53 The studies in Nicaragua 41 and Mexico40 showed that the use of the tool during family planning consultations improved provider participatory behaviours as well as patient participation in decision making.40, 41, 44, 51 Like the Indonesian study of patient coaching, these decision aid interventions included provider training on how to effectively use the tool and some briefings on counselling skills. The use of this tool was initiated by the health‐care providers during client encounters, which may have created an environment where clients felt safe and encouraged to play an active role. The more recent study from Iran also reinforced the positive effects of the DMT and provider training on patient participation in decision making.44

Our results highlight that the early studies in our review were international aid‐funded in low‐ and middle‐income settings, testing the transfer of Western country‐developed concepts such as patient‐centred counselling and shared decision making. The key effective components were as follows: (a) provider communication skills training in patient‐centred counselling; (b) ongoing supervision, peer review and self‐assessment of provider participatory communication and counselling skills; (c) targeted and tailored patient communication skills coaching or training; and (d) provision of a decision aid, to be used during the consultation by the provider.

By contrast, more recent studies included in this review (n = 9) were from high‐ and upper‐middle‐income East Asian countries (Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and mainland China).37, 42, 43, 45, 46, 48, 54 Decision aids which met the IPDAS criteria were predominately tested in the studies from East Asia (5/8), especially since 2013.42, 43, 45, 46, 48 These studies mainly assessed the effect on decisional conflict; the three RCT studies42, 43, 48 within this group showed mixed and inconsistent results. However, as noted earlier, the non‐RCT PDA studies from East Asia which had provider47 or patient communication training39, 45, 46 components resulted in significant improvements to patient participation.

It is worth noting that a recent Special Issue on Shared Decision Making (SDM) published in conjunction with the International Shared Decision‐Making Conference in Lyon 2017 reported on the status of SDM implementation in over 20 countries.55 By contrast to the previous special issue in 2011,56 this issue included articles from several non‐Western countries and regions (Africa, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Iran, Malaysia, Peru and Taiwan).55 Most of these countries reported a growing interest in patient participation but faced challenges in implementation. Therefore, at this time, there is a unique opportunity to expand and implement the evidence we have highlighted in this review. Ironically, the earliest work in non‐Western low‐income countries which showed considerable efficacy has not progressed and should be urgently revisited.

Our review was not able to explore specific cultural aspects of patient participation, but it did highlight the potential for this to be successfully achieved, particularly if provider training is incorporated. Learnings from the studies that used IPC should be particularly noted, due to the unique way that they emphasized reducing social distance, an aspect of culture not strongly featured in Western countries. Social distance can be a ‘virtual barrier’ between providers and patients created by the subjective feelings of alienation in class and status due to age, sex, race and social, educational, economic and cultural backgrounds.50 Therefore, such cultural and local aspects of patient‐provider communication in non‐Western should not be overlooked when designing interventions to promote patient active participation.

One of the limitations of this systematic review is that we focused our systematic review on participation in dyadic decision making amongst patients living in non‐Western countries. We acknowledge that family and significant others can play a significant role in the process of decision making in some patients from non‐Western cultural backgrounds.57 However, one recent study58 has suggested this may be less homogenous within cultures than previously thought. Another limitation is that we only included studies that were published in English and were identified from major databases in medical research. To draw more complete conclusions on the evidence from non‐Western countries, a comprehensive search of the literature in non‐Western country‐specific databases that collect local language studies might be needed in the future.

In conclusion, people in non‐Western countries can successfully be involved in their health‐care decisions, and this should not be overlooked as this is a core component of a people‐centred health‐care system as advocated by the Alma‐Ata Declaration and the WHO framework for IPCHS. Our study highlights the ability of communication skills training for patients and providers to increase patient participation and involvement in health‐care decisions. Such intervention strategies should be further developed and implemented as a priority in non‐Western countries regardless of their income status.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Dolan H, Li M, Trevena L. Interventions to improve participation in health‐care decisions in non‐Western countries: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Health Expect. 2019;22:894–906. 10.1111/hex.12933

Funding information

Financial support for this study was provided by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)/Centres of Research Excellence project: Testing, Translation and Uptake of Evidence in General Practice: A systems approach to rapid translation. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing and publishing the report.

Data Availability Statement: Data for this systematic review were derived from published articles which are available in the public domain and may be subject to copyright. Relevant data supporting the conclusions of this systematic review are included within the article and supporting files.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data for this systematic review were derived from published articles which are available in the public domain and may be subject to copyright. Relevant data supporting the conclusions of this systematic review are included within the article and supporting files.

REFERENCES

- 1. Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W, Van Hecke A. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient‐centeredness in hospital care: a concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(12):1923‐1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Osborn R, Squires D. International perspectives on patient engagement: results from the 2011 Commonwealth Fund Survey. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2012;35(2):118‐128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:Cd001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Durand M‐A, Carpenter L, Dolan H, et al. Do interventions designed to support shared decision‐making reduce health inequalities? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gravel K, Légaré F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision‐making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health professionals' perceptions. Implement Sci. 2006;1(1). 10.1186/1748-5908-1-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bruera E, Willey JS, Palmer JL, Rosales M. Treatment decisions for breast carcinoma: patient preferences and physician perceptions. Cancer. 2002;94(7):2076‐2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shepherd HL, Tattersall MH, Butow PN. Physician‐identified factors affecting patient participation in reaching treatment decisions. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1724‐1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization . Declaration of Alma Ata: International conference on primary health care. Paper presented at: Alma Ata, USSR: International Conference on Primary Health Care; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Topp SM, Call AS. for papers—the Alma Ata Declaration at 40: reflections on primary healthcare in a new era. BMJ Global Health. 2018;3(2):e000791. [Google Scholar]

- 10. WHO . Framework on integrated people‐centred health services; 2016. http://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/framework/en/. Accessed February 27, 2017.

- 11. WHO . Framework on integrated people‐centred health services: an overview; 2016. http://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/fullframe.pdf?ua=1. Accessed February 27, 2017.

- 12. Hoffmann TC, Légaré F, Simmons MB, et al. Shared decision making: What do clinicians need to know and why should they bother? Med J Aust. 2014;201:35‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walczak A, Mazer B, Butow PN, et al. A question prompt list for patients with advanced cancer in the final year of life: development and cross‐cultural evaluation. Palliat Med. 2013;27(8):779‐788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) . Australian charter of healthcare rights 2007. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Charter-PDf.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2018.

- 15. Nathan AG, Marshall IM, Cooper JM, Huang ES. Use of decision aids with minority patients: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):663‐676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Obeidat RF, Homish GG, Lally RM. Shared decision making among individuals with cancer in non‐western cultures: a literature review. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:454‐463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Back MF, Huak CY. Family centred decision making and non‐disclosure of diagnosis in a South East Asian oncology practice. Psychooncology. 2005;14(12):1052‐1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Setlhare V, Couper I, Wright A. Patient‐centredness: Meaning and propriety in the Botswana, African and non‐Western contexts. Afr J Primary Health Care Family Med. 2014;6:1‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moore M. What does patient‐centred communication mean in Nepal? Med Educ. 2008;42(1):18‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Claramita M, Nugraheni M, van Dalen J, van der Vleuten C. Doctor–patient communication in Southeast Asia: a different culture? Adv Health Sci Educ. 2013;18(1):15‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee YK, Lee PY, Cheong AT, et al. Share or not to share: Malaysian healthcare professionals' views on localized prostate cancer treatment decision making roles. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0142812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ng C‐J, Lee P‐Y, Lee Y‐K, et al. An overview of patient involvement in healthcare decision‐making: a situational analysis of the Malaysian context. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):1‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. UN . United Nations regional groups of member states; 2014. http://www.un.org/depts/DGACM/RegionalGroups.shtml. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 25. Ito E, Walker GJ, Liang H. A systematic review of non‐Western and cross‐cultural/national leisure research. J Leisure Res. 2014;46(2):226. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1918‐1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gionfriddo MR, Leppin AL, Brito JP, et al. A systematic review of shared decision making interventions in chronic conditions: a review protocol. Syst Rev. 2014;3:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Covidence systematic review software . www.covidence.org. Accessed June 01, 2016.

- 29. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group . Data extraction template; 2016. http://cccrg.cochrane.org/author-resources. Accessed July 23, 2016.

- 30. Higgins J, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343: d5928‐d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non‐randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 1998;52(6):377‐384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Prod ESRC Methods Progr Version. 2006;1:b92. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roter D, Rosenbaum J, de Negri B, Renaud D, DiPrete‐Brown L, Hernandez O. The effects of a continuing medical education programme in interpersonal communication skills on doctor practice and patient satisfaction in Trinidad and Tobago. Med Educ. 1998;32(2):181‐189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brown LD, de Negri B, Hernandez O, Dominguez L, Sanchack JH, Roter D. An evaluation of the impact of training Honduran health care providers in interpersonal communication. Int J Qual Health Care. 2000;12(6):495‐501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim Y‐M, Figueroa ME, Martin A, et al. Impact of supervision and self‐assessment on doctor–patient communication in rural Mexico. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002;14(5):359‐367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim YM, Putjuk F, Basuki E, Kols A. Self‐assessment and peer review: improving Indonesian service providers' communication with clients. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;4–12. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maclachlan EW, Shepard‐Perry MG, Ingo P, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of patient education and empowerment to improve patient‐provider interactions in antiretroviral therapy clinics in Namibia. AIDS Care ‐ Psychol Socio‐Med Aspects AIDS/HIV. 2016;28(5):620‐627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kim YM, Putjuk F, Basuki E, Kols A. Increasing patient participation in reproductive health consultations: an evaluation of "Smart Patient" coaching in Indonesia. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50(2):113‐122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. An SY, Kim GH, Kim JY. Effectiveness of shared decision‐making training program in people with schizophrenia in South Korea. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2017;53(2):111‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim YM, Kols A, Martin A, et al. Promoting informed choice: evaluating a decision‐making tool for family planning clients and providers in Mexico. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2005;31(4):162‐171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim YM, Davila C, Tellez C, Kols A. Evaluation of the World Health Organization's family planning decision‐making tool: improving health communication in Nicaragua. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(2):235‐242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lam WW, Chan M, Or A, Kwong A, Suen D, Fielding R. Reducing treatment decision conflict difficulties in breast cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(23):2879‐2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Osaka W, Nakayama K. Effect of a decision aid with patient narratives in reducing decisional conflict in choice for surgery among early‐stage breast cancer patients: a three‐arm randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(3):550‐562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Farrokh‐Eslamlou H, Aghlmand S, Eslami M, Homer CS. Impact of the World Health Organization's Decision‐Making Tool for Family Planning Clients and Providers on the quality of family planning services in Iran. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2014;40(2):89‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shum J, Lam W, Choy B, Chan J, Ho WL, Lai J. Development and pilot‐testing of patient decision aid for use among Chinese patients with primary open‐angle glaucoma. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2017;2(1):e000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Torigoe I, Shorten A. Using a pregnancy decision support program for women choosing birth after a previous caesarean in Japan: a mixed methods study. Women Birth. 2018;31(1):e9‐e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hu J, Yu H, Shao J, Li Z, Wang J, Wang Y. An evaluation of the dental 3D multimedia system on dentist‐patient interactions: a report from China. Int J Med Inf. 2008;77(10):670‐678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gong HS, Park JW, Shin YH, Kim K, Cho KJ, Baek GH. Use of a decision aid did not decrease decisional conflict in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shirai Y, Fujimori M, Ogawa A, et al. Patients' perception of the usefulness of a question prompt sheet for advanced cancer patients when deciding the initial treatment: a randomized, controlled trial. Psycho‐Oncology. 2012;21(7):706‐713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Negri DB, Brown D, Hernández O, Rosenbaum J, Roter D. Improving interpersonal communication between health care providers and clients. Quality Assurance Methodol Refinement Ser, Center for Human Services (CHS). 1997;12:2013. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Johnson SL, Kim YM, Church K. Towards client‐centered counseling: development and testing of the WHO Decision‐Making Tool. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81(3):355‐361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. World Health Organization . Decision‐making tool for family planning clients and providers [electronic resource]; 2005.

- 53. Comminit ; 2002. http://www.comminit.com/global/content/information-and-knowledge-optimal-health-project-info-global. Accessed May 10, 2018.

- 54. World Bank . Historical classification by income in XLS format, World Bank country and lending classification. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed June 10, 2018.

- 55. Zeitschrift fur Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualitat im Gesundheitswesen. 2017;123‐124(International Accomplishments in Shared Decision Making). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56. Zeitschrift fur Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualitat im Gesundheitswesen. 2011;105 (Policy and practice developments in the implementation of shared decision making: an international perspective). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57. Mead EL, Doorenbos AZ, Javid SH, et al. Shared decision‐making for cancer care among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):e15‐e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Alden DL, Friend J, Lee PY, et al. Who decides: me or we? Family involvement in medical decision making in eastern and western countries. Med Decis Making. 2017;38(1):14‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Review Manager (Revman) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data for this systematic review were derived from published articles which are available in the public domain and may be subject to copyright. Relevant data supporting the conclusions of this systematic review are included within the article and supporting files.