Abstract

The first complete genome of the biotechnologically important species Sulfobacillus thermotolerans has been sequenced. Its 3 317 203-bp chromosome contains an 83 269-bp plasmid-like region, which carries heavy metal resistance determinants and the rusticyanin gene. Plasmid-mediated metal resistance is unusual for acidophilic chemolithotrophs. Moreover, most of their plasmids are cryptic and do not contribute to the phenotype of the host cells. A polyphosphate-based mechanism of metal resistance, which has been previously unknown in the genus Sulfobacillus or other Gram-positive chemolithotrophs, potentially operates in two Sulfobacillus species. The methylcitrate cycle typical for pathogens and identified in the genus Sulfobacillus for the first time can fulfill the energy and/or protective function in S. thermotolerans Kr1 and two other Sulfobacillus species, which have incomplete glyoxylate cycles. It is notable that the TCA cycle, disrupted in all Sulfobacillus isolates under optimal growth conditions, proved to be complete in the cells enduring temperature stress. An efficient antioxidant defense system gives S. thermotolerans another competitive advantage in the microbial communities inhabiting acidic metal-rich environments. The genomic comparisons revealed 80 unique genes in the strain Kr1, including those involved in lactose/galactose catabolism. The results provide new insights into metabolism and resistance mechanisms in the Sulfobacillus genus and other acidophiles.

Subject terms: Applied microbiology, Bacterial genomics

Introduction

Extremely acidophilic chemolithotrophic microorganisms (ACM) form a unique group of polyextremophiles due to their ability to adapt to diverse extreme factors, including exceptionally low pH (≤1) and high concentrations of toxic heavy metals and metalloids. These microorganisms are present in ore deposits, coal mines, acid hot springs, hydrothermal vents, and acid mine drainage1. Ferrous iron (Fe2+), elemental sulfur (S0), reduced sulfur compounds (S2−), and hydrogen serve as inorganic electron donors and energy sources in different ACM. These characteristics make it possible to use the communities of acidophilic chemolithotrophic bacteria and archaea in biohydrometallurgical (biomining) approaches for the recovery of precious and non-ferrous metals2–6. Nowadays, biomining is applied worldwide and recognized as a more environmentally friendly and economically advantageous method for processing of sulfide raw materials.

Bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus, which are common inhabitants of extremely acidic metal-rich ecological niches, are successfully used in the bioleaching/biooxidation of sulfide ores (including refractory pyrite–arsenopyrite gold-bearing ores) and ore concentrates. Members of the genus Sulfobacillus play a leading role in both Fe2+ and S0/S2− oxidation in the communities of ACM1,7,8. Previous studies of carbon and energy metabolism have shown that bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus are facultative chemolithotrophs with an optimal mixotrophic type of growth in the presence of organic matter (0.02–0.05%). They are also capable of chemoorganoheterotrophic growth during several or continuous transfers9,10. Sulfobacillus isolates use yeast extract and glucose as carbon and energy sources under mixotrophic and heterotrophic conditions11. They are also facultative anaerobes capable of ferric iron respiration12–15.

The genus Sulfobacillus currently includes three moderately thermophilic species and one subspecies: S. thermosulfidooxidans16, S. thermosulfidooxidans subsp. asporogenes17, S. acidophilus18, and S. sibiricus19. S. thermotolerans20 and S. benefaciens13 are two known thermotolerant species. Two genomes of S. acidophilus21,22 and five genomes of S. thermosulfidooxidans23–25 have been previously reported. Five more genomes assigned to S. thermosulfidooxidans, S. benefaciens, and S. acidophilus have been discussed26. In total, nine genomes of S. thermosulfidooxidans, two genomes of S. benefaciens, three genomes of S. acidophilus, and two genomes of Sulfobacillus spp. are available in the GenBank databases. Plasmid sequences of S. thermotolerans L15 and Y0017 have been published and analyzed27.

The object of the present research is S. thermotolerans, which is applied in bioleaching/ biooxidation of sulfidic ores and ore concentrates, containing precious (gold and silver) and non-ferrous metals. This thermotolerant species is of high industrial importance in the biotechnologies for sulfidic raw material processing at temperatures above 35 °C in the presence of elevated concentrations of toxic components2,20,28–32. S. thermotolerans proved to be resistant to high ambient concentrations of Zn2+ (>765 mM), Cu2+ (>80 mM), and Pb2+ (>2 mM)33. For S. thermosulfidooxidans, the minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of Cu2+, Ni2+, and Zn2+, respectively, were >230, 292, and >800 mM34. In contrast to Sulfobacillus species, MIC of Cu2+, Cd2+, Ni2+, and Zn2+ for metal tolerant Cupriavidus metallidurans and Escherichia (E.) coli were 3–13 mM35 and 0.5–4 mM36,37, respectively.

Our research aims at providing new insights into the metabolic pathways and resistance mechanisms in bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus and ACM in general. Here we present the first complete genome of the species S. thermotolerans and its comparison to other Sulfobacillus genomes. In addition to genome analysis, this work describes phenotypic and phylogenetic characteristics of Sulfobacillus species. We focus on the features that have been previously unknown in the genus Sulfobacillus, differentiate S. thermotolerans from other Sulfobacillus organisms or are unusual for acidophilic chemolithotrophs.

Results

General description of S. thermotolerans Kr1 genome

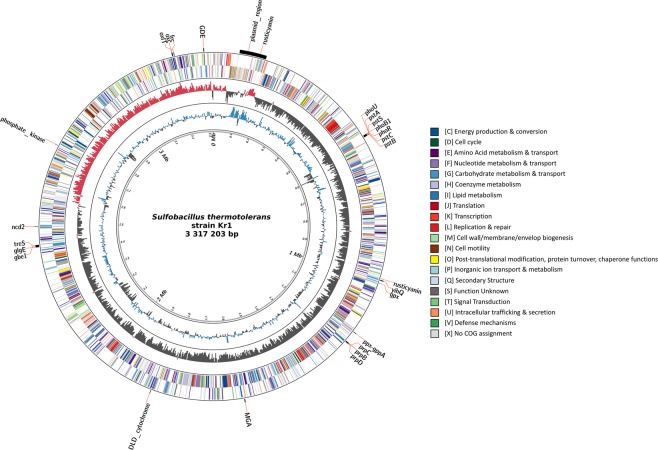

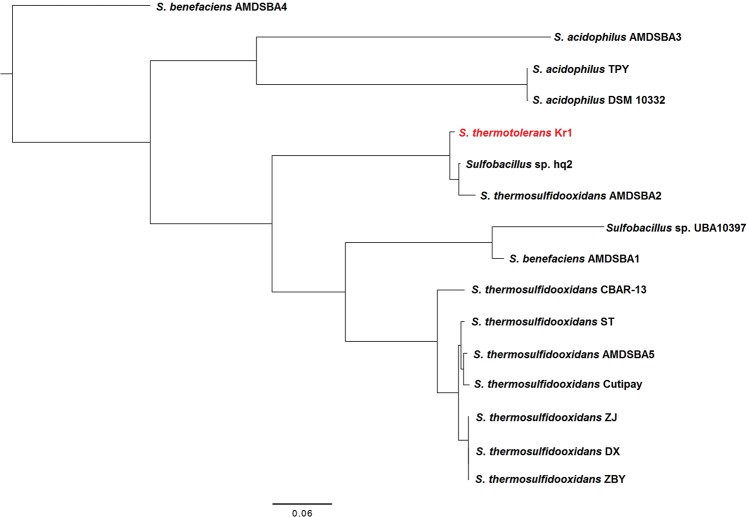

The genome of S. thermotolerans Kr1T consists of one circular chromosome (3 317 203 bp) with an overall G + C content of 52.4% (Fig. 1, Table 1). A total of 3239 genes were predicted. Among them, 3121 protein-coding genes, 67 non-translated RNAs, and 51 pseudogenes were identified. Genes with unclear functions were annotated as hypothetical proteins. Analysis of gene ontology and functional annotation of genes were carried out. The genome of S. thermotolerans Kr1 was compared to all available Sulfobacillus genomes to reveal species-specific and strain-specific features of S. thermotolerans Kr1. A total of 80 genes (proteins) turned out to be unique in the strain Kr1 (Table S1). Among them, we identified possible plasmid, transposon, and phage integrations, as well as MFS transporters, zinc metalloprotease, putative c-type cytochrome, components of the lactose/galactose catabolism, and a large number of hypothetical proteins of unknown functions. Figure 2 shows the phylogenetic position of S. thermotolerans Kr1 among Sulfobacillus strains. The phylogenetic tree is a consensus tree inferred from all orthogroups and constructed using the STAG (Species Tree Inference from All Genes) method. Sulfobacillus sp. hq2 proved to be the closest phylogenetic relative of the type strain Kr1.

Figure 1.

Circular map of the Sulfobacillus thermotolerans Kr1 genome. Rings from the outside in: (1) genes of interest and plasmid region; (2) protein-coding genes on the forward strand (color-coded by the functional categories, see legend); (3) protein-coding genes on the reverse strand (color-coded by the functional categories, see legend); (4) GC skew; (5) G + C content; (6) scale marks. Abbreviations of the genes and relevant proteins: GDE, glycogen debranching enzyme [EC 3.2.1.133]; phoU, phosphate transport system protein; pstA, phosphate transport system permease protein; pstS, phosphate transport system substrate-binding protein; phoB1, phosphatase synthesis response regulator PhoP; phoR, phosphate regulon sensor histidine kinase PhoR [EC:2.7.13.3]; pstC, phosphate transport system permease protein; pstB, phosphate transport system ATP-binding protein; yihQ, alpha-glucosidase [EC 3.2.1.20]; gpx, glutathione peroxidase [EC:1.11.1.9]; ppx-gppA, exopolyphosphatase/guanosine-5′-triphosphate,3′-diphosphate pyrophosphatase [EC 3.6.1.11 3.6.1.40]; prpC, 2-methylcitrate synthase [EC 2.3.3.5]; prpB, methylisocitrate lyase [EC 4.1.3.30]; prpD, 2-methylcitrate dehydratase [EC 4.2.1.79]; MGA, glucoamylase [EC 3.2.1.3]; DLD_cytochrome, D-lactate dehydrogenase (cytochrome) [EC 1.1.2.4]; treS, maltose alpha-D-glucosyltransferase/alpha-amylase [EC 5.4.99.16 3.2.1.1]; glgE, starch synthase (maltosyl-transferring) [EC 2.4.99.16]; gbe1; 1,4-alpha-glucan branching enzyme [EC 2.4.1.18]; ncd2, nitronate monooxygenase [EC 1.13.12.16].

Table 1.

Statistics of the genome of Sulfobacillus thermotolerans Kr1.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 3317203 | 100.00 |

| DNA Coding region (bp) | 2842887 | 85.70 |

| DNA G + C content (bp) | 1738272 | 52.40 |

| Number of replicons | 2 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 3239 | 100.00 |

| RNA genes | 67 | 2.06 |

| rRNA operons | 6 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 3121 | 96.36 |

| Pseudo genes | 51 | 1.57 |

| Genes with function prediction | 2716 | 83.85 |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 522 | 16.72 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2175 | 67.15 |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 2393 | 73.88 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 83 | 2.56 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 842 | 25.99 |

| CRISPR repeats | 4 (6) |

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic position of Sulfobacillus thermotolerans Kr1 among other strains of the genus Sulfobacillus. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the STAG (species tree inferred from all orthogroups) method (https://github.com/davidemms/STAG; OrthoFinder software package99) and visualized with FigTree v.1.4.3 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). The tree is a consensus species tree from trees from all orthogroups (in which all Sulfobacillus strains were present).

Identification and characterization of the plasmid-like region integrated into the chromosome of S. thermotolerans Kr1

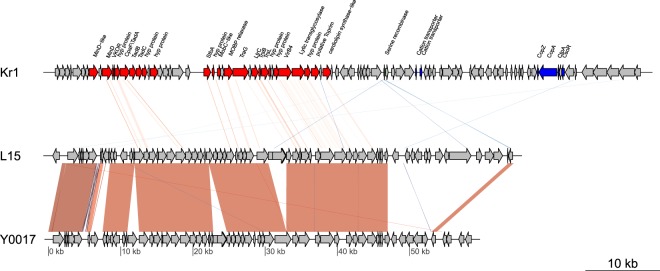

No extrachromosomal plasmids were identified in the strain Kr1, although each of the closest phylogenetic relatives, S. thermotolerans L15 and Y0017, carried cryptic plasmids (65 903 and 59 212 bp, respectively) with 63.5% overall nucleotide sequence similarity between them27. However, we identified a putative 83 269-bp plasmid region (ORFs BXT84_00415–00865) integrated into the chromosome of the strain Kr1 (Figs 1, 3 and Table S2). The G + C content of this region was 56–58%, which was higher than 52.4% G + C content of the chromosomal DNA (Fig. S1, Table 1).

Figure 3.

The plasmid-like region of the Sulfobacillus thermotolerans Kr1 genome aligned with the plasmid sequences of S. thermotolerans L15 and S. thermotolerans Y0017. The genes on the S. thermotolerans Kr1 chromosome, homologous to the genes of S. thermotolerans L15 and Y0017 plasmids, are colored red. Homologs involved in metal resistance are colored blue. The red bars connecting the plasmid genes represent direct orthologous matches. The blue bars represent reversed matches. Darker colors correspond to higher blast scores. Table S2 contains detailed information on the homology levels of the genes. The regions of high homology between the plasmids pL15 and pY0017 are colored red. Abbreviations: VKOR, vitamin K epoxide reductase; hyp protein, hypothetical protein; MOBP relaxase, MOBP-type family relaxase.

Out of 46 ORFs located within a 40 944-bp fragment of the plasmid region, 26 of them showed close homology to the plasmid sequences of S. thermotolerans L15 and Y0017 (Figs 3, S2 and Table S2). A common “backbone” region coding for a probable plasmid stability system and nonpheromone conjugation system containing homologs of both type IV and II secretion systems (T4SS and T2SS) of pL15 and pY001727 was identified. The genes of the common backbone region encode the MinD-like protein, CpaF-like (TadA) Flp pilus assembly ATPase-like proteins and TadB/TadC-like proteins (putative T2SS), StbA family protein (plasmid stability), relaxase, TraG-like coupling protein (a conjugation protein involved in T4SS), LtrC-like protein (primase), TrsL/TrsB putative conjugation proteins, VirB4-like protein (T4SS), and putative lytic transglycosylase (Table S2). The pL15 and pY0017 plasmids and a 40 944-bp fragment of the identified plasmid region of the strain Kr1 share accessory genes and the genes encoding eight hypothetical proteins (Fig. 3, Table S2). They include hypothetical vitamin K epoxide reductase, the phosphatidylserine/phosphatidylglycerophosphate/cardiolipin synthase-like protein, and two hypothetical proteins (ORFs BXT84_00480 and BXT84_00500) unique for the genus Sulfobacillus (28 and 26% a. a. identity to the cytochrome c-type biogenesis protein of Myxococcus sp. and cytochrome c-type biogenesis protein CcmF of Glaciecola arctica, respectively). The Kr1 plasmid-like region harbors a transposon containing the transposase gene (ORF BXT84_00675) with the closest similarity to Desulforudis audaxviator and Desulfosporosinus acidophilus transposases. Resolvases of the strain Kr1 are homologous to the resolvase-like proteins of pL15 and pY0017.

At the same time, the determination of possible integrations into the chromosome of S. thermotolerans Kr1 revealed a putative integrative and conjugation element (ICE with T4SS) within the candidate plasmid-like region (ORFs BXT84_00415–00770). However, in addition to the features of the ICE, this integrated element contained the genes specific for plasmids and the backbone and accessory genes similar to those of pL15 and pY0017 (Table S2). We, therefore, suggest that this region of the Kr1 chromosome was derived from the conjugative plasmid, which could be inserted into the genome as a result of the transposition of the Tn3-like mobile element (IS5; ORF BXT84_00675). Similarly, the genome of S. acidophilus TPY contains the genes of S. acidophilus NAL plasmids, integrated into two sites of the chromosome22.

We also revealed other probable gene integrations upstream of the region of homology between pL15, pY0017, and the plasmid-like region of the strain Kr1. Tn3 (ORF BXT84_00730), a transposase (ORF BXT84_00780) similar to the transposase of Rhodopirellula baltica, and Tn7 (ORFs BXT84_00850–BXT84_00865) could mediate them. Many genes encoded by the putative plasmid region of S. thermotolerans Kr1 are non-related to any genes of sequenced Sulfobacillus genomes (Tables S1 and S2). They are homologous to the genes of phylogenetically distinct microorganisms and, therefore, were likely acquired by horizontal gene transfer (HGT).

Interestingly, the plasmid-like region of S. thermotolerans Kr1 carries genetic determinants of resistance to heavy metals. These are a cation transporter homologous to that of Acidithiobacillus (At.) ferrooxidans and a protein homolog of the Co/Zn/Cd transporter (cation diffusion facilitator family) of Alicyclobacillus (Al.) macrosporangiidus. The putative integrated plasmid also codes for a copper chaperone (CopZ), two copper-translocating P-type ATPases (CopA and CtpA), and a copper-sensitive operon repressor (CsoR) (Fig. 3, Table S2). Moreover, the plasmid-like region encodes rusticyanin and a hypothetical protein homologous to the conserved hypothetical electron transporter (rnfE) of Thiolapillus brandeum (41% similarity; 82% coverage), which may be components of electron transport chains.

Specific characteristics of carbon and energy metabolism

TCA cycle

We identified all the genes encoding the TCA cycle enzymes, including 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH) complex, in S. thermotolerans Kr1 (Table S3). OGDH activity was measured in cell-free extracts of S. thermotolerans Kr1 grown at optimal (40 °C) and limiting (12 and 55 °C) growth temperatures under mixotrophic conditions. The OGDH protein possessed no detectable enzymatic activity at optimal and suboptimal (12 °C) temperatures. However, an increase in the growth temperature from 40 to 55 °C induced OGDH activity from zero to 6.7–6.9 nmol/min mg protein (enzyme assays were carried out in three replicates).

Glyoxylate and methylcitrate cycles

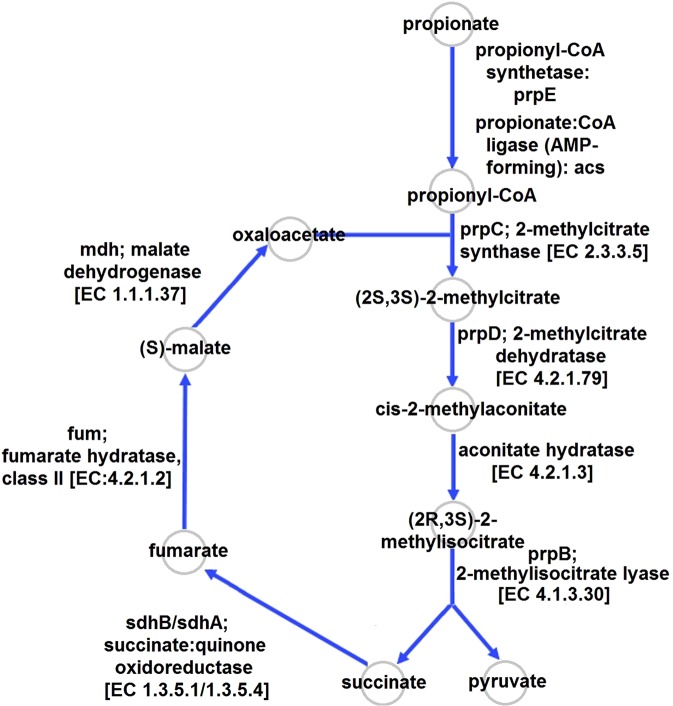

The glyoxylate cycle of S. thermotolerans Kr1 is incomplete due to the absence of the isocitrate lyase gene, although the malate synthase gene is present in the genome of this strain (Table S3). Nevertheless, genome analysis revealed the genes encoding the methylcitrate cycle in S. thermotolerans Kr1 (Fig. 4, Table S4). The key methylcitrate cycle enzymes—2-methylcitrate synthase (MCS), 2-methylcitrate dehydratase, and methylisocitrate lyase (MCL)—were identified. The comparison of the genome of the strain Kr1 to other Sulfobacillus genomes indicated the genes encoding these enzymes only in S. thermosulfidooxidans, S. benefaciens, and the strain hq2. The key methylcitrate cycle enzymes of these species share 73–99.5% a. a. identity (97–100% coverage). MCS activity in the extracts of the Kr1 cells grown in the medium containing propionate (0.02–0.08%) was shown to increase with an increase in propionate content in the cultivation medium. The values of MCS activity were close in the presence of 0.02–0.04% propionate: 30.9–34.2 units/min mg protein. When concentrations of propionate were increased to 0.06 and 0.08%, MCL activities reached 51.8–55.4 and 70.2–72.5 units/min mg protein, respectively. At the same time, the maximal cell yields decreased (2.1–2.2 and 1.5–1.8 × 108 cells/ml in the presence of 0.02–0.04 and 0.06–0.08% propionate, respectively) in comparison with the optimal mixotrophic variant (3.5 × 108 cells/ml).

Figure 4.

The methylcitrate cycle predicted in Sulfobacillus thermotolerans Kr1. Arrows indicate reactions catalyzed by the enzymes encoded in the genome.

Oxalate degradation

The gene cluster coding for the formyl-CoA transferase (Frc) and oxalyl-CoA decarboxylase (Oxc) enzymes and the oxalate: formate antiport protein (OxlT) gene were identified in S. thermotolerans Kr1 (Table S5). These proteins are involved in the oxalate degradation pathway. The genomic comparisons between the members of the genus Sulfobacillus indicated that S. thermotolerans, Sulfobacillus sp. hq2, S. benefaciens, and S. acidophilus harbored all three proteins of this pathway. The level of identity (a. a.) between the proteins of S. thermotolerans Kr1 and other Sulfobacillus species was within 72‒100% (95‒100% coverage).

Lactose and galactose catabolism

The components of the lactose–galactose catabolism pathway were identified in the S. thermotolerans Kr1 genome. It codes for α- and β-galactosidases, as well as other proteins of lactose/galactose catabolism (transporters and Lac I family transcriptional regulator, in particular) (Table S1). No other Sulfobacillus genomes encode these proteins. Most of the closest protein homologs belong to bacteria of the genus Alicyclobacillus, which are also members of the communities of ACM. The closest homologs of α- and β-galactosidases of the strain Kr1 belong to Paenibacillus and Alicyclobacillus spp. (52–57% similarity; 94–99% coverage) and Thermoanaerobacter and Alicyclobacillus spp. (46–47.1% similarity; 96–98% coverage), respectively. The Lac I family transcriptional regulator was most similar to that of Alicyclobacillus spp. (47.2–48.3% similarity; 96–97% coverage). The closest homologs of the carbohydrate ABC transporter permease, lactose ABC transporter permease, and sugar ABC transporter substrate-binding protein belonged to Alicyclobacillus spp. as well: 61.2–65.9% similarity (99–100% coverage), 62.2–67.2% similarity (97–98% coverage), and 49.6–64.2% similarity (91–98% coverage), respectively.

Ferrous iron oxidation and electron transfer chain

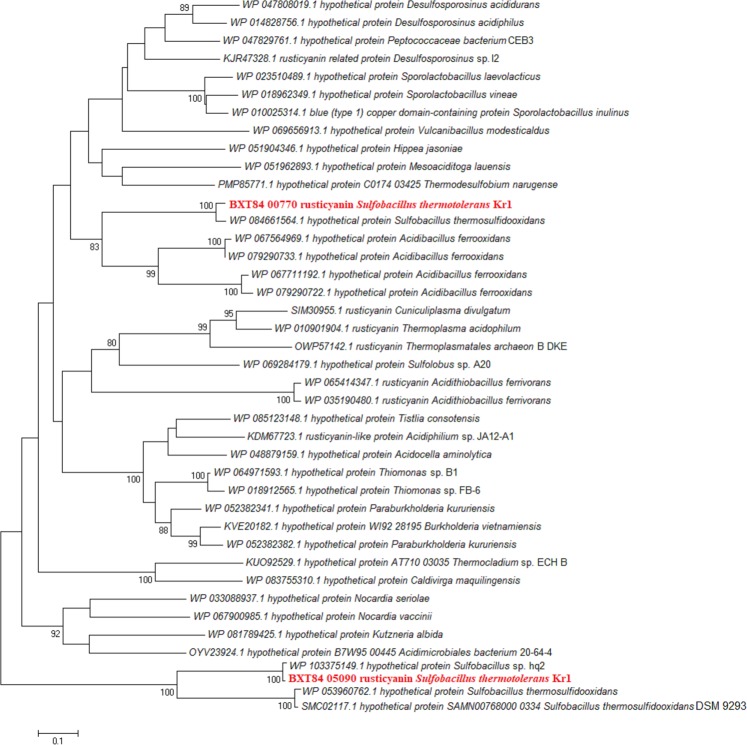

Table S6 shows electron transfer components encoded in the genome of S. thermotolerans Kr1. Interestingly, we identified two genes coding for rusticyanins. The results of alignment indicated a 30% a. a. similarity between these rusticyanins (Fig. S3). A comparison of their amino acid sequences to protein databases and subsequent phylogenetic analysis showed the following. Apart from the hypothetical protein of S. thermosulfidooxidans 9293 (96% a. a. similarity; 100% coverage), the proteins of Acidibacillus ferrooxidans proved to be the closest homologs of the rusticyanin-like protein of the strain Kr1 (42–43% a. a. similarity; 62–68% coverage). Thus, the rusticyanin-like proteins of S. thermotolerans Kr1 and S. thermosulfidooxidans 9293 occupy a common branch in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5). Another rusticyanin of the strain Kr1, together with the closest rusticyanin homolog of Sulfobacillus sp. hq2 (99.3% similarity; 100% coverage), shows a 53–54% a. a. similarity (100% coverage) to S. thermosulfidooxidans proteins. Therefore, rusticyanins of these Sulfobacillus species form a common cluster, which consists of two separate branches (Fig. 5). The rusticyanin-related protein of Desulfosporosinus sp. is the next closest protein to this rusticyanin of the strain Kr1 (35% a. a. identity; 80% coverage).

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic positions of the rusticyanin proteins of Sulfobacillus thermotolerans Kr1. The phylogenetic tree was constructed in MEGA7109. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor-joining method110. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method112. The analysis involved 40 amino acid sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 87 positions in the final dataset. The percentage of replicate trees, in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates), are shown next to the branches111 (values lower than 80% are hidden).

Three genes of S. thermotolerans Kr1 were annotated as sulfocyanins with the closest homology to the sulfocyanin proteins of the strain hq2 and S. benefaciens. The genome of the strain Kr1 also encodes three cytochromes c homologous to the proteins of other bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus.

While the bc1 complex was not identified in the strain Kr1, cytochrome b subunit of the bc1 complex (2 copies) and NADH dehydrogenase (14 subunits and F-type ATPase) were present (Table S6). S. thermotolerans Kr1 contained the genes coding for three terminal oxidase complexes. Components of the cytochrome c oxidase (three clusters of the coxBAC genes), cytochrome aa3 menaquinol oxidase (qoxABCD), and three copies of the cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase were identified (Table S6).

Stress resistance and defense systems

Oxidative stress defense

We revealed several enzymes, which were associated with defense mechanisms against reactive oxygen species in the strain Kr1 (Table S7). Glutathione (GSH) peroxidase was found only in the Kr1 and hq2 strains. The closest homologs of the GSH peroxidase of S. thermotolerans belong to Al. macrosporangiidus and Aphanothece hegewaldii. The genome of the strain Kr1 harbors superoxide dismutase (SOD) and several peroxiredoxins/alkyl hydroperoxide reductases, which are also present in S. thermosulfidooxidans and S. acidophilus genomes26, as well as in the strain hq2 and S. benefaciens (this study). Atypical 2-cys peroxiredoxin was revealed in S. thermotolerans Kr1, Sulfobacillus sp. hq2, and two strains of S. acidophilus and S. thermosulfidooxidans. GSH peroxidase and SOD possessed activities of 4.4–4.6 units/min mg protein in cell-free extracts of S. thermotolerans Kr1 grown at partial pressure of atmospheric oxygen. When S. thermotolerans cells were subsequently cultivated at intense aeration, activities of antioxidant enzymes increased from 4.5–4.6 to 36.9–38.9 units/min mg protein (GSH peroxidase) and from 4.4–4.5 to 57.0–61.2 units/min mg protein (SOD). Thus, activities of these two enzymes of the oxidative stress defense were up-regulated in response to active aeration.

Resistance to heavy metals and metalloids

Apart from the metal resistance determinants localized within the putative chromosome integrated plasmid, the genome of S. thermotolerans Kr1 encodes other metal resistance systems. Similarly to other species of the genus Sulfobacillus, metal efflux, which involves metal ion efflux proteins24, can be an essential mechanism of defense against heavy metals in the cells of S. thermotolerans Kr1. Thus, metal efflux can occur via transport systems composed of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily and major facilitator superfamily (MFS) proteins, as well as cation translocating P-type ATPases (Table S7). The genome of S. thermotolerans Kr1 encodes another resistance determinant: the MerA mercuric reductase. The genes participating in the mechanisms of resistance to arsenic were identified in S. thermotolerans Kr1 as well (Table S7). Although the repressor of the arsenic resistance operon (ArsR) was present in S. thermotolerans Kr1, no arsenate reductase (ArsC) was identified. S. thermosulfidooxidans strains Cutipay23 and ST24 contained the arsC and arsR genes. The two-gene ars operon is speculated to give resistance to only trivalent metalloid salts of As, whereas ArsC is required for arsenate resistance38. At the same time, the ArsA/ArsB ATPase pump predicted to export arsenite and antimonite39 was found in S. thermotolerans Kr1 and all other sequenced Sulfobacillus genomes.

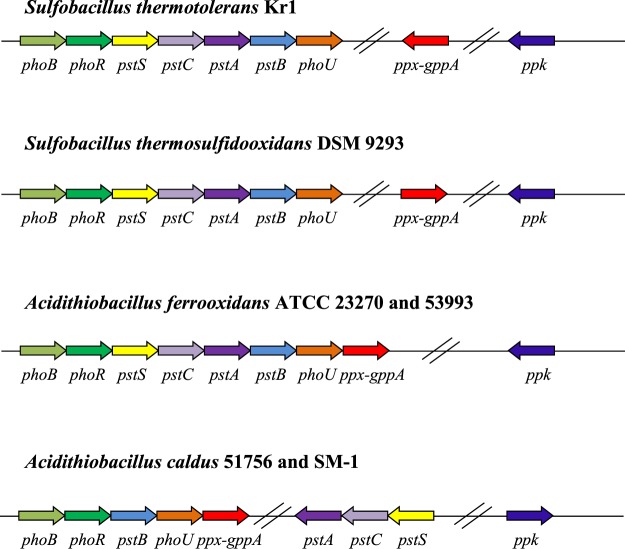

For the first time, we identified a putative Pho regulon consisting of phoB, phoR, pstS, pstC, pstA, pstB, and phoU, as well as the ppx and ppk genes, in S. thermotolerans Kr1 and bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus in general (Fig. 6, Table S7). These genes are involved in the polyP-based mechanism of resistance to heavy metals. The comparison of the genome of S. thermotolerans Kr1 to other Sulfobacillus genomes available in the databases revealed a putative polyP-based resistance mechanism in S. thermosulfidooxidans as well: 61–62 and 70% a. a. identity for PPK and PPX, respectively, and 76–100% a. a. identity for the proteins encoded by the Pho regulon. We also identified the Pho regulon genes in S. acidophilus genomes, which, however, lacked the ppk and ppx genes.

Figure 6.

Putative Pho regulon and the polyphosphate kinase and exopolyphosphatase genes, involved in the polyphosphate-based mechanism of metal resistance in Sulfobacillus thermotolerans Kr1 and S. thermosulfidooxidans DSM 9293 (the genome sequence accession number NZ_FWWY00001), in comparison to those of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and At. caldus strains41. Abbreviations of the genes encoding the corresponding proteins: phoB, phosphatase synthesis response regulator PhoP; phoR, phosphate regulon sensor histidine kinase PhoR; pstS, phosphate transport system substrate-binding protein; pstC, phosphate transport system permease protein; pstA, phosphate transport system permease protein; pstB, phosphate transport system ATP-binding protein; phoU, phosphate transport system protein; ppx-gppA, exopolyphosphatase/guanosine-5′-triphosphate,3′-diphosphate pyrophosphatase; ppk, polyphosphate kinase.

Discussion

Some ACM, including members of the genus Sulfobacillus, were shown to withstand extremely high concentrations of heavy metals in the environment33,34,40,41. Heavy metals and metalloids reach high concentrations in the mine drainage waters, industrial bioleaching tanks, mine deposits, and sulfide ore heaps. S. thermotolerans Kr1 is tolerant to high concentrations of zinc, copper and other heavy metals (more than 1–2 orders of magnitude higher in comparison to the majority of the known organisms)33. Extremely high resistance of S. thermotolerans Kr1 to heavy metals is of particular interest since communities of ACM resistant to high concentrations of metals are essential for the efficient microbial stage of oxidation in industrial processes. Analysis of the first sequenced genome of S. thermotolerans, together with other results reported in the current paper, provided new insights into resistance capacities of this species.

In general, the exact mechanisms of extreme resistance in ACM are still not evident41. Analyses of the ACM genomes revealed metal resistance determinants varying in content and quantity. Acidophilic chemolithotrophs harbor metal resistance systems responsible for import and efflux of heavy metal ions, as well as their extra- and intracellular sequestration and transformation to less toxic compounds24,41–44. At the same time, the presence of an increased number of metal resistance genes has not been shown to increase resistance in acidophiles45. High metal resistance was found to be associated with complexation of free metals by sulfate ions and passive tolerance to metal influx via an internal positive cytoplasmic transmembrane potential45.

The study of the expression of the genes determining resistance to copper in At. ferrooxidans, together with comparative proteomics, revealed regulation of the copper resistance genes and proteins in response to Cu. Thus, RND-type Cus systems and different RND-type efflux pumps were up-regulated, while the proteins involved in the influx of cations into the cell were down-regulated41,43,46–50. Analysis of transcriptional expression in the cells of Ferroplasma (F.) acidarmanus and Sulfolobus (Sl.) metallicus archaea, exposed to high copper, indicated increased transcript levels of several copper resistance determinants. At the same time, the proteomic study of these archaea revealed only the regulation of protein expression associated with energy production and conversion, biosynthesis of amino acids, and general stress response44,51. No regulation of expression of the components of the zinc resistance system was revealed in the cells of At. caldus and Acidimicrobium (Am.) ferrooxidans in response to zinc either, while an increased synthesis of the efflux Zn transporter and several hypothetical proteins of unknown functions was observed in F. acidarmanus52. However, the published data do not provide a complete understanding of the phenomenon of extreme metal resistance, which can involve unknown mechanisms of defense, and give no information about the mechanisms of metal resistance in the genus Sulfobacillus.

Our data indicate that apart from the identified metal resistance determinants common for ACM and listed above and in Table S7, S. thermotolerans probably uses an additional mechanism for metal resistance, which has not been previously known in Gram-positive ACM (Fig. 6). This mechanism is based on the metal ion sequestration with polymers of inorganic polyphosphate (polyP) and has been reported in several acidophilic archaea and Gram-negative bacteria. Thus, a polyP-dependent copper resistance mechanism was proposed for polyP-accumulating acidophiles: At. ferrooxidans53, Sulfolobus metallicus54, Metallosphaera sedula, At. thiooxidans43,55,56, and At. caldus52. The polyphosphate kinase (PPK) enzyme catalyzes the reversible conversion of the terminal phosphate of ATP into polyP, which is hydrolyzed to inorganic phosphate by exopolyphosphatase (PPX). Inorganic phosphate, in turn, binds metal cations forming a metal-phosphate complex transported out of the cell by phosphate transporters. In E. coli, the ppk and ppx genes belong to the same operon and are co-regulated at the transcriptional level. Thus, accumulation of polyP granules is not observed in E. coli, since the PPK and PPX catalyze opposite reactions57. In At. ferrooxidans and At. caldus, the ppk and ppx genes are located in different operons (Fig. 6), which implicates separate regulation of polyP synthesis and degradation41,58. These Acidithiobacillus isolates were also shown to contain putative Pho regulons different from each other and from the Pho regulons of other bacteria41,52,58. The genetic organization of the components of the polyP mechanism in S. thermotolerans Kr1 turned out to be different from those of the known ACM. Thus, in contrast to acidithiobacilli, the PPX and PPK of the strain Kr1 were separated from the pho and pst genes and did not belong to the same operon either (Fig. 6). In our previous paper, we showed the presence of polyphosphate granules in the cells of S. thermotolerans Kr129. A comparison to other Sulfobacillus genomes revealed that the type strain S. thermosulfidooxidans 9293, which is also highly resistant to heavy metals34,40,43, harbored all the components for the polyP-dependent mechanism as well (Fig. 6). These two Sulfobacillus species, which are highly resistant to metals (in contrast to S. acidophilus and S. benefaciens that are tolerant to lower metal content in the environment13,33,34,40), together with the ACM listed above, seem to possess the polyP-dependent mechanism, which can also contribute to the extreme metal tolerance.

Interestingly, S. thermotolerans Kr1 carried genetic determinants of heavy metal resistance, which probably belonged to the putative chromosome integrated conjugative plasmid containing homologs of both type IV and II secretion systems (T4SS and T2SS) (Fig. 3, Table S2). A putative integrative and conjugation element (ICE) with T4SS, identified within this region, was probably integrated into the chromosome of the Kr1 strain as a part of the plasmid or separately from other integrations that are located upstream of the ICE region. It should be noted that most ACM harbor cryptic plasmids, which do not contribute to the phenotype of the host cells. Localization of heavy metal resistance determinants on plasmids or integrative and conjugative elements is not typical for acidophilic chemolithotrophs. These genes are primarily located on the chromosomes outside mobile element regions or integrated extrachromosomal elements. The determinants of copper resistance, located within the genomic island of the Gram-negative bacterium At. ferrooxidans ATCC 5399347, and determinants of zinc resistance, localized on the megaplasmid of At. caldus SM-159, are exceptions reported to date. The copper resistance genes are also suggested to be present within the metagenomic island in the At. ferrivorans genome60.

The functions of the metal resistance determinants identified within the integrated plasmid of S. thermotolerans Kr1 are associated with the tolerance to copper and some other bivalent cations of heavy metals. The repressor encoded on the plasmid of the strain Kr1 responds to stressors, including Cu2+, Zn2+, Ag+, Cd2+, and Ni2+ ions61, while P-type ATPases and copper chaperones transfer metal ions such as Cu2+, Cd2+, Co2+, and Zn2+ 62,63. However, while the copA, copZ, and csoR genes are also localized on the chromosome of S. thermotolerans Kr1, other metal resistance determinants of the integrated plasmid are present only within the plasmid region. The involvement of the rusticyanin gene localized in the vicinity of these metal determinants in metal resistance mechanisms is also not excluded. Thus, the CopZ-like protein and periplasmic rusticyanin of At. ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 contributed to its high-level copper resistance64. In this bacterium, copper cupredoxins (rusticyanin, in particular) not only function as components of the ferrous iron oxidation pathway but also may bind excess copper in the periplasm, most likely playing a role in high copper resistance64.

Our previous study of the polymorphism of plasmid profiles in different Sulfobacillus strains revealed alterations in the number of S. thermotolerans Kr1 plasmids (from one to three) depending on the presence of heavy metals in the cultivation media. The variant grown in the medium with high concentrations of zinc contained a single plasmid33. This may indicate that the stable integration of the plasmid into the chromosome was relatively recent during the period when the strain Kr1 was maintained in our laboratory. Localization of the metal resistance determinants on plasmids can be advantageous under the conditions of extremely high concentrations of heavy metals in the natural and technogenic habitats specific for ACM.

Our current research revealed new data on the carbon metabolism in bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus as well. Although all the genes encoding the TCA cycle enzymes were identified in all Sulfobacillus genomes, the TCA cycle was supposed to be incomplete due to the lack of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH) activity9. The cell-free extracts of S. thermotolerans Kr1 grown under mixotrophic, organotrophic or autotrophic conditions lacked OGDH activity29, similarly to S. sibiricus65, S. thermosulfidooxidans, and S. thermosulfidooxidans subsp. asporogenes9. We detected no OGDH activity in the cell-free extracts of S. thermosulfidooxidans and S. thermosulfidooxidans subsp. asporogenes, grown in the presence of high zinc (0.8 M Zn2+) in the medium or low ambient pH 1.266. The results obtained in the present study confirmed our previous data on zero OGDH activity in S. thermotolerans Kr1 at 40 and 12–14 °C29. Nevertheless, the change in the temperature of cultivation from 40 to 55 °C induced OGDH activity. It was also detected in two thermophilic species of the genus Sulfobacillus under stress growth conditions: at the limiting growth temperature of 18 °C (S. sibiricus N1) and under unfavorable autotrophic conditions (S. thermosulfidooxidans) (our unpublished data). Thus, the incomplete TCA cycle could switch to the complete version under specific adverse conditions. The disrupted TCA cycle does not generate energy (no ATP or reductive equivalents are produced) but provides precursors for biosynthetic processes. However, when Sulfobacillus organisms endure stress, a complete TCA cycle fulfills its common energetic function and probably provides for a higher respiration rate required to withstand such conditions.

In the present work, we revealed only one key enzyme of the glyoxylate bypass, malate synthase, encoded in the genome of S. thermotolerans Kr1; the isocitrate lyase gene was not identified. The biochemical study of the cell-free extracts of the Kr1 strain indicated no isocitrate lyase activity either, irrespective of the growth temperature or nutrition type, whereas malate synthase activity was detected under all cultivation conditions29. S. thermosulfidooxidans, S. thermosulfidooxidans subsp. asporogenes, and S. sibiricus lacked the functional glyoxylate bypass either9,65. At the same time, the glyoxylate cycle plays a vital role in anaplerosis, converting acetyl-CoA (derived from the oxidation of both odd- and even-chain length fatty acids) into oxaloacetate (the intermediate of the citric acid cycle)67,68.

However, we identified the genes coding for the key enzymes of the methylcitrate cycle previously unknown in the genus Sulfobacillus (Fig. 4). This cycle is a modified version of the TCA cycle, and it metabolizes propionyl-CoA generated by β-oxidation of odd-chain-length fatty acids and converts it into pyruvate69. Our prior study revealed that cultivation of S. thermosulfidooxidans, S. sibiricus, and S. thermotolerans resulted in the accumulation of propionate and acetate in the media under the conditions of oxygen deficiency and the continuous consumption of these exometabolites during the subsequent growth14. In natural habitats and biotechnological processes, bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus can be subjected to unfavorable conditions of decreased oxygen content (e.g., in sulfide ore deposits, thermal springs, bioleaching heaps, and zones of bioleaching tanks with poor aeration), when propionate is accumulated. The culture liquid contained propionate (0.9 mg/l) at the late-exponential phase of growth of S. thermotolerans at atmospheric oxygen partial pressure (without intense aeration) in the medium supplemented with Fe2+, yeast extract, and glucose14. Propionate and its derivative were also detected among the metabolites of S. thermotolerans Kr1, which predominated in the communities of ACM forming biofilms on the pyrite-arsenopyrite ore concentrate in the presence of yeast extract (0.02%) in percolators (our unpublished data). In the present study, we showed that S. thermotolerans Kr1 was capable of growth in the presence of propionate (0.02–0.08%) under mixotrophic conditions. The growth parameters decreased gradually with an increase in propionate concentration, indicating the toxic effect of the latter.

The methylcitrate pathway is predominantly found in pathogenic bacteria: Neisseria meningitides, Salmonella enterica, E. coli, Mycobacterium (M.) tuberculosis, and M. smegmatis70. These microorganisms use the methylcitrate pathway to utilize propionate for carbon and energy and/or to prevent its intracellular accumulation to toxic levels. Thus, propionate catabolism can be an alternative detoxification mechanism71,72. In our current study, we analyzed other Sulfobacillus genomes for the presence of the key enzymes of the methylcitrate cycle as well. Apart from S. thermotolerans, the genes encoding these enzymes were revealed in S. thermosulfidooxidans and S. benefaciens. Remarkably, we identified no genes encoding the components of the methylcitrate cycle in S. acidophilus. On the contrary, the complete glyoxylate cycle containing both isocitrate lyase and malate synthase was predicted only in S. acidophilus TPY and 1033226. Enzyme assays revealed an increase in 2-methylcitrate synthase activity (MCS, the key enzyme of the methylcitrate cycle) in the cell-free extracts of S. thermotolerans in response to increased concentrations of propionate in the medium of growth. Similar direct interrelations between the propionate concentration and MCS activity were shown for S. thermosulfidooxidans DSM 9293 and S. sibiricus N1 (our unpublished data). We suggest that propionyl-CoA conversion to pyruvate in the methylcitrate cycle and further to PEP can contribute to the replenishment of biosynthesis precursors (anaplerosis) and gluconeogenesis in the Sulfobacillus strains that lack anaplerotic glyoxylate cycle. The methylcitrate cycle can also be a detoxification mechanism.

In contrast to all other Sulfobacillus genomes, the genome of the strain Kr1 contains the genes involved in the catabolism of lactose and galactose. The closest homologs of the lactose catabolism proteins of the strain Kr1 belong to Alicyclobacillus species, which are also members of acidophilic chemolithotrophic communities. Therefore, we suggest that these genes were acquired by S. thermotolerans Kr1 as a result of HGT. It is unclear whether corresponding proteins can function in this strain. Nevertheless, β-galactosidase of Al. acidocaldarius proved to be thermostable, highly active and potentially useful as a commercial product for lactose hydrolysis73.

Ferrous iron oxidation in the Sulfobacillus genus is another aspect, which is of both environmental and biotechnological importance. Although the investigation of this problem started almost 30 years ago74–78, Fe2+ oxidation in bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus is still poorly understood. The initial electron transfer components accepting electrons directly from Fe2+ remain to be elucidated.

In the present study, we identified two rusticyanin genes in S. thermotolerans Kr1. These rusticyanins proved to occupy separate branches in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5). S. acidophilus lacks homologs of rusticyanins typically found in iron-oxidizing acidophiles24. The rusticyanin proteins were annotated only in the species S. thermosulfidooxidans and the strain AMDSB526. Rusticyanins are periplasmic blue copper proteins, which are components of electron transport chains involved in the oxidation of ferrous iron and reduced sulfur compounds in Gram-negative chemolithotrophic bacteria and some archaea79–81. Interestingly, the role of rusticyanins in Gram-positive ACM, which differ from Gram-negative bacteria in the cell wall structure, is unclear. We suggest that identified rusticyanins can participate in the initial stages of the ferrous iron oxidation process in S. thermotolerans Kr1. Rusticyanins, together with cytochromes c, may also be involved in Fe3+ respiration system82–84.

Sulfocyanins (the blue copper redox proteins commonly found in archaea) encoded in the genome of the strain Kr1 were previously identified in S. thermosulfidooxidans strains24,25,78. A high level of expression of sulfocyanins was registered in the cells of S. thermosulfidooxidans ST grown on the medium with ferrous iron24. These proteins belong to the archaeal cluster of sulfocyanins.

The presence of the cytochrome c, rusticyanin, and sulfocyanin genes in the genome of S. thermotolerans Kr1 may suggest that the membrane-bound cytochrome c directly reduced by Fe2+ transfers electrons to sulfocyanin, rusticyanin or other components of the transport chain. All sequenced Sulfobacillus genomes were shown to harbor one or few cytochrome c copies, except for S. benefaciens AMDSBA126. Identification of the prosthetic cytochrome groups in the cells of S. thermotolerans Kr1 predicted the presence of heme c29.

The bc1 complex, functioning in reverse and encoded by the petI operon85, was not identified in the strain Kr1. Only the strain AMBDSBA4 (divergent from the known Sulfobacillus species) was predicted to harbor bc complex, which can be involved in the reverse electron transfer26. The genome of S. thermotolerans Kr1 encodes only a cytochrome b subunit of the bc1 complex (2 copies) (Table S6), similarly to S. acidophilus and S. thermosulfidooxidans genomes. NADH dehydrogenase (14 subunits and F-type ATPase) is present as well. The terminal oxidase complexes (cytochrome c oxidase, cytochrome aa3 menaquinol oxidase, and bd ubiquinol oxidase) identified in S. thermotolerans Kr1 are probably responsible for the terminal stage of iron oxidation. S. thermosulfidooxidans TH1, S. acidophilus ALV, and S. sibiricus N1 possessed cytochrome aa3-type oxidase activity74–76, while S. thermosulfidooxidans DSM 9293 yielded spectra dominated by a-type cytochromes77. Cytochromes and cytochrome oxidases were upregulated during the growth of S. thermosulfidooxidans DSM 9293 when the chalcopyrite ore concentrate was the sole source of iron78.

The genes involved in oxalate degradation were revealed in bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus for the first time. They were identified in S. thermotolerans, S. benefaciens, and S. acidophilus species. Some oxalate-degrading microorganisms are known to use oxalate as a carbon and energy source, while others do not require oxalate for growth and decompose it at concentrations toxic for cells86–88. The presence of these genes in the S. thermotolerans Kr1 genome implies high metabolic capacities of this thermotolerant species, as well as the possible detoxification mechanism against high concentrations of oxalate.

S. thermotolerans has developed a more complex antioxidant system in comparison to other species of the genus Sulfobacillus. This system consists of superoxide dismutase (SOD), several peroxiredoxins/alkyl hydroperoxide reductases, 2-cys peroxiredoxin, and glutathione (GSH) peroxidase, which reduces hydroperoxides by GSH. The genomic comparisons revealed that no other species of the genus Sulfobacillus harbored GSH peroxidase. At the same time, oxidative stress is one of the main factors inhibiting microbial growth and substrate oxidation under aerobic conditions89. Diverse redox-active metal ions (iron, copper, cobalt, and nickel) also cause oxidative stress90. Biotank processes of leaching of sulfide raw materials by microbial communities (including bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus) are associated with intense aeration and metal accumulation in the liquid phase. Our results showed that GSH and SOD activities in S. thermotolerans Kr1 depended on the aeration mode and increased 8.3–13.3 times at intense aeration. Thus, the induction of the antioxidant defense enzymes, including GSH peroxidase, is one of the strategies of S. thermotolerans Kr1 against adverse effects of intense aeration. Since the closest homologs of the GSH peroxidase belong to phylogenetically distinct microorganisms, the GSH peroxidase gene was probably acquired by S. thermotolerans as a result of HGT.

This work reports the first sequenced and annotated genome of the biotechnologically significant species S. thermotolerans isolated from the industrial process. Analysis of its genome sequence, genomic comparisons to other Sulfobacillus, as well as physiological and biochemical characteristics, provide new insights into versatile metabolic pathways and resistance mechanisms in the genus Sulfobacillus. We suggest that the probable plasmid-mediated resistance to heavy metals, propionate metabolism, methylcitrate cycle, effective oxidative stress defense, oxalate degradation, as well as flexible carbon and energy metabolism, gave this strain a competitive advantage in the communities of ACM under unstable conditions of natural metal-rich environments and industrial bioleaching processes.

Our data on the S. thermotolerans Kr1 genes and proteins, which are phylogenetically distinct from those of Sulfobacillus strains and similar to those of other microbial taxa that inhabit the same environments, indicate genetic exchange between members of the communities of ACM. These proteins are involved in metabolic and resistance systems, which suggests that HGT played a vital role in the development of the highly resistant phenotype of S. thermotolerans. Future research should further develop our findings on resistance to heavy metals and toxic compounds, defense strategies against unfavorable factors, constructive metabolism, and energy processes in bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus. The results will help to gain deeper understanding of ecological functions of Sulfobacillus organisms and interactions among members of the natural and industrial communities of acidophilic chemolithotrophs.

Material and Methods

Cultivation of S. thermotolerans Kr1

S. thermotolerans strain Kr1T (VKM B-2339T = DSM 17362T)20 was cultivated at 39 ± 1°С in 2500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 1500 ml of the modified 9K medium91 supplemented with yeast extract (0.02%, wt/vol). The 9K medium contained the following (g/l): (NH4)2SO4, 3.0; KCl, 0.1; KH2PO4, 0.5; MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.5; Ca(NO3)2 · 4H2O, 0.01; and FeSO4 · 7H2O, 15 g/l (36 mM Fe2+). The pH values and concentrations of Fe3+ and Fe2+ were measured as described31. The solutions of H2SO4 (10 N) and NaHCO3 (20%) were used to adjust the initial pH value to 1.8. The amount of inoculum was 10% (vol/vol).

S. thermotolerans Kr1 used for the subsequent genome sequencing was grown in the medium of the abovementioned composition, supplemented with 400 mM Zn2+. To determine 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase activity, S. thermotolerans Kr1 was grown under mixotrophic conditions at optimal (40°С) and nonoptimal (12 and 55°С) temperatures. The cultivation was carried out with mixing by air agitation (sterile air was supplied at a flow rate of 2 l min–1) in Redline RI53 incubators (Binder, Germany).

For measurements of antioxidant enzyme activities, S. thermotolerans Kr1 was cultivated in the modified 9K medium containing ferrous iron and yeast extract at atmospheric oxygen partial pressure or intense aeration. Methylcitrate synthase was determined in the extracts of the cells grown at atmospheric oxygen partial pressure in the medium containing ferrous iron, yeast extract, and propionate (0.02, 0.04, 0.06, and 0.08%).

Microscopy and quantitative assessment of cells

Quantitative assessment of the strain Kr1 cells was carried out by direct counts in the Goryaev chamber and by the method of serial terminal tenfold dilutions31. A Mikmed-2 microscope (LOMO, Russia) equipped with a phase contrast device was used.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Late-exponential cells of S. thermotolerans Kr1 were collected by centrifugation (10 000 g, 15 min, 4 °C) and washed twice with acidified 9K medium without energy sources (pH 1.8) for the subsequent genome sequencing. Total DNA was extracted by phenol/chloroform method with the lysis buffer containing the following: 1 M sucrose; 150 mM NaCl; 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0); 50 mM EDTA; lysozyme, 2 mg/ml (Sigma, Germany); and proteinase K, 0.5 mg/ml (Sigma, Germany). Genome sequencing was performed using the Roche 454 Life Sciences Genome Sequencer GS FLX+ Genetic Analyzer (Roche 454 Life Science, United States) according to the standard protocol for a shotgun genome library. Assembly of raw sequencing reads with an average length of 694 bases was performed by the GS de novo assembly software Newbler version 2.9 (Roche 454 Life Science, United States). Primary assembly resulted in 46 contigs (>2000 bp in size) and an estimated genome size of 3.3 Mb. Relevant amplicons were generated and sequenced by conventional Sanger capillary methods on ABI Prism 3730 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, United States; Hitachi, Japan) to fill the gaps between contigs. After gaps between contigs were filled, the size of the full sequence of the circular chromosome was 3 317 203 bp.

Genome annotation and analysis

The complete genome sequence of S. thermotolerans Kr1 was annotated using Prokka v1.1092 and the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (United States, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/annotation_prok/).

Functional characterization of the genome of S. thermotolerans Kr1 was carried out using the KOALA (KEGG Orthology and Links Annotation) system93. Local BLAST (BlastX threshold e-value = 1 × 10−6, BLOSUM-62 matrix) and the nr database were used. Blast2GO was also used to analyze gene ontology and to functionally annotate genes (COG, PFAM, and signal peptides). G + C content and skew were calculated by gcSkew.pl script (https://github.com/abremges/2015-pseudo). Positions of the genes and plasmid insertions, COG, GC-skew, and G + C content were drawn using Circos94. MetaCyc95 and Pathway collages96 were used to construct metabolic maps.

Glimmer 3, a system for finding genes in microbial DNA, was used to analyze target regions containing the genes of interest97,98. Unknown proteins were annotated using the HHpred server for protein remote homology detection (https://toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/#/tools/hhpred). The annotation was manually improved by further comparison to the Sulfobacillus genomes. We used annotated genome sequences of 16 phylogenetically diverse strains assigned to S. acidophilus, S. thermosulfidooxidans, S. benefaciens, and Sulfobacillus spp. hq2 and UBA10397, available in the NCBI GenBank databases (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/?term=Sulfobacillus), for the nucleotide and protein sequence comparisons. The sequences were compared using the NCBI Basic Local Alignment Tool (United States, https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and by analysis of orthology groups (OG).

Protein sequences for OG were obtained from 16 Sulfobacillus strains using the NCBI databases. OGs were obtained using the OrthoFinder software with default parameters99. The phylogenetic tree showing the position of Sulfobacillus strains was constructed using the STAG (Species Tree Inference from All Genes) method (https://github.com/davidemms/STAG), which is built into the algorithms of the OrthoFinder software program99. The phylogenetic tree was visualized using FigTree v.1.4.3 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Plasmid-like region analysis

We used the method of GC profiling to identify the boundaries of the plasmid region in the chromosome100,101. The ICEberg web-based resource102 (http://db-mml.sjtu.edu.cn/ICEberg/) and the web-based ICEfinder tool for the detection of ICEs/IMEs in the bacterial genomes (http://202.120.12.136:7913/ICEfinder/ICEfinder.html) were also used to identify the integrated DNA elements. The candidate plasmid region containing the putative ICE was aligned with the pL15 plasmid sequence of S. thermotolerans L15 (NC_025041) and pY0017 sequence of S. thermotolerans Y0017 (NC_016040), using Mauve 2.4.0103 and BlastN algorithm (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Visualization was carried out with the GenoPlotR package104.

Enzyme assays

In order to determine the specific enzyme activities of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH, EC 1.2.4.2), superoxide dismutase (SOD, EC 1.15.1.1), glutathione (GSH) peroxidase (EC 1.11.1.9), and 2-methylcitrate synthase (MCS) (EC 2.3.3.5), late-exponential cells were collected by centrifugation (10 000 g, 15 min, 4 °C). The cell precipitates were washed twice with acidified 9K medium (pH 1.8) without energy sources and resuspended in 0.1 M Tris HCl buffer (pH 7.4) (OGDH), 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) (SOD and GSH peroxidase), or HEPES-NaOH buffer (pH 7.1) (MCS). Cell-free extracts were obtained by pellet sonification using the UZDN-2T ultrasonic disintegrator (Russia) (1.5 min with 2-min intervals for cooling, four times; 22 Hz, 40 mA) and centrifuged at 40 000 g (4 °C, 30 min). The supernatant was assayed for the enzymatic activity of OGDH (nmol/min mg protein) judged from NAD reduction in the presence of 2-oxoglutarate, thiamine pyrophosphate, and coenzyme A105. SOD activity was determined in the cell-free extracts by the inhibition of the reduction of nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT); one unit of SOD activity was that amount of SOD, which inhibited the reaction by 50%106. GSH peroxidase activity was assayed in the cell-free extracts by a decrease in NADPH content in the reaction mixture107. MCS activity was determined by the oxalate-stimulating production of free propionyl-CoA71. A PE-5400UV spectrophotometer (ECROS, Russia) was used for enzyme activity assays. Protein content was measured by the Lowry method108.

Alignments and phylogenetic analysis of proteins

The protein sequences were aligned using the NCBI BlastP algorithm (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), MEGA7109, and the Lasergene software package ver. 8.1.3(4) (DNASTAR, Inc., United States).

The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the MEGA7109 software package. Evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor-joining method110 and amino acid sequences of phylogenetically close microbial proteins. The bootstrap test (1000 replicates) was applied111. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method112 and are in the units of the number of amino acid substitutions per site.

Statistics

The experiments, including enzyme assays, were carried out in three parallels with 3–5 replicates; the significance of the results was assessed using the Student’s t-test at the significance level P ≤ 0.05.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor T.F. Kondrat’eva for valuable comments and discussion of the work. This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation.

Author contributions

A.E.P. and A.V.L. conceived the work that led to the submission. A.E.P., A.V.L., E.S.K. and V.V.B. participated in the design of work. A.E.P., V.V.B., O.V.S., A.S.N., M.A.L. and I.A.T. carried out experimental work. A.E.P., A.V.L., E.S.K. and V.V.B. interpreted the results. A.E.P. drafted the manuscript. V.V.B. and A.E.P. prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Data availability

The genome sequence of S. thermotolerans Kr1 was deposited in the GenBank databases under the accession number CP019454 and is public at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/CP019454.1?report=genbank. Sequence read achieve (SRA) was submitted under SRA accession number SRP143515.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-51486-1.

References

- 1.Kondrat’eva TF, et al. Diversity of the communities of acidophilic chemolithotrophic microorganisms in natural and technogenic ecosystems. Microbiology. 2012;81:1–24. doi: 10.1134/S0026261712010080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dopson M, Lindstrӧm EB. Analysis of community composition during moderately thermophilic bioleaching of pyrite, arsenical pyrite, and chalcopyrite. Microb. Ecol. 2004;48:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s00248-003-2028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vera M, Schippers A, Sand W. Progress in bioleaching: part A: fundamentals and mechanisms of bacterial metal sulfide oxidation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;97:7529–7541. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-4954-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brierley CL, Brierley JA. Progress in bioleaching: part B: applications of microbial processes by the minerals industries. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;97:7543–7552. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niu J, et al. The shift of microbial communities and their roles in sulfur and iron cycling in a copper ore bioleaching system. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34744. doi: 10.1038/srep34744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaksonen, et al. Recent progress in biohydrometallurgy and microbial characterisation. Hydrometallurgy. 2018;180:7–25. doi: 10.1016/j.hydromet.2018.06.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bond PL, Druschel GK, Banfield JF. Comparison of acid mine drainage microbial communities in physically and geochemically distinct ecosystems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:4962–4971. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.11.4962-4971.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rawlings DE, Johnson DB. The microbiology of biomining: development and optimization of mineral-oxidizing microbial consortia. Microbiology. 2007;153:315–324. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/001206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsaplina IA, et al. Carbon metabolism in Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans subsp. asporogenes, strain 41. Microbiology. 2000;69:271–276. doi: 10.1007/BF02756732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karavaiko GI, et al. Growth and carbohydrate metabolism of sulfobacilli. Microbiology. 2001;70:245–250. doi: 10.1023/A:1010463007138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhuravleva AE, Ismailov AD, Tsaplina IA. Electron donors at oxidative phosphorylation in bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus. Microbiology. 2009;78:811–814. doi: 10.1134/S0026261709060228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bridge TAM, Johnson DB. Reduction of soluble iron and reductive dissolution of ferric iron-containing minerals by moderately thermophilic ironoxidizing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998;64:2181–2186. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.6.2181-2186.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson DB, Joulian C, d’Hugues P, Hallberg KB. Sulfobacillus benefaciens sp. nov., an acidophilic facultative anaerobic Firmicute isolated from mineral bioleaching operations. Extremophiles. 2008;12:789–798. doi: 10.1007/s00792-008-0184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsaplina IA, et al. Response to oxygen limitation in bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus. Microbiology. 2010;79:13–22. doi: 10.1134/S0026261710010029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hedrich S, Johnson DB. Aerobic and anaerobic oxidation of hydrogen by acidophilic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2013;349:40–45. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golovacheva RS, Karavaiko GI. Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans gen. nov., sp. nov., a facultatively thermophilic organism isolated from a sulfide ore deposit. Microbiology. 1978;47:815–822. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vartanyan NS, Pivovarova TA, Tsaplina IA, Lysenko AM, Karavaiko GI. New thermoacidophilic bacterium of the genus Sulfobacillus. Microbiology. 1988;57:268–274. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norris PR, Clark DA, Owen JP, Waterhouse S. Characteristics of Sulfobacillus acidophilus sp. nov. and other moderately thermophilic mineralsulphide-oxidizing bacteria. Microbiology. 1996;142:775–783. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-4-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melamud VS, et al. Sulfobacillus sibiricus sp. nov., a new moderately thermophilic bacterium. Microbiology. 2003;72:681–688. doi: 10.1023/A:1026007620113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogdanova TI, et al. Sulfobacillus thermotolerans sp. nov., a thermotolerant, chemolithotrophic bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006;56:1039–1042. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li B, Chen Y, Liu Q, Hu S, Chen X. Complete genome analysis of Sulfobacillus acidophilus strain TPY, isolated from a hydrothermal vent in the Pacific Ocean. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:5555–5556. doi: 10.1128/JB.05684-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson I, et al. Complete genome sequence of the moderately thermophilic mineral-sulfide-oxidizing firmicute Sulfobacillus acidophilus type strain (NAL(T)) Stand. Genomic. Sci. 2012;6:1–13. doi: 10.4056/sigs.2736042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Travisany D, et al. Draft genome sequence of the Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans Cutipay strain, an indigenous bacterium isolated from a naturally extreme mining environment in Northern Chile. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:6327–6328. doi: 10.1128/JB.01622-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo X, et al. Comparative genome analysis reveals metabolic versatility and environmental adaptations of Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans strain ST. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, et al. Adaptive evolution of extreme acidophile Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans potentially driven by horizontal gene transfer and gene loss. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;83:e03098–16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03098-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Justice NB, et al. Comparison of environmental and isolate Sulfobacillus genomes reveals diverse carbon, sulfur, nitrogen, and hydrogen metabolisms. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deane SM, Rawlings DE. Two large, related, cryptic plasmids from geographically distinct isolates of Sulfobacillus thermotolerans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:8175–8180. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06118-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan GL, et al. Culturable and molecular phylogenetic diversity of microorganisms in an open-dumped, extremely acidic Pb/Zn mine tailings. Extremophiles. 2008;12:657–664. doi: 10.1007/s00792-008-0171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsaplina IA, et al. Phenotypic properties of Sulfobacillus thermotolerans: Comparative aspects. Microbiology. 2008;77:654–664. doi: 10.1134/S0026261708060027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bulaev AG, et al. Changes in the species composition of a thermotolerant community of acidophilic chemolithotrophic microorganisms upon switching to the oxidation of a new energy substrate. Microbiology. 2012;81:391–396. doi: 10.1134/S0026261712040029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panyushkina AE, Tsaplina IA, Grigor’eva NV, Kondrat’eva TF. Thermoacidophilic microbial community oxidizing the gold-bearing flotation concentrate of a pyrite-arsenopyrite ore. Microbiology. 2014;83:539–549. doi: 10.1134/S0026261714040146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Panyushkina AE, Tsaplina IA, Kondrat’eva TF, Belyi AV, Bulaev AG. Physiological and morphological characteristics of acidophilic bacteria Leptospirillum ferriphilum and Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans, members of the chemolithotrophic microbial consortium. Microbiology. 2018;87:326–338. doi: 10.1134/S0026261718030086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tupikina OV, et al. Strain polymorphism of the plasmid profiles in Sulfobacillus species. Microbiology. 2009;78:593–597. doi: 10.1134/S0026261709050105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watkin ELJ, et al. Metals tolerance in moderately thermophilic isolates from a spent copper sulfide heap, closely related to Acidithiobacillus caldus, Acidimicrobium ferrooxidans and Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009;36:461–465. doi: 10.1007/s10295-008-0508-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monsieurs P, et al. Heavy metal resistance in Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 is governed by an intricate transcriptional network. Biometals. 2011;24:1133–1151. doi: 10.1007/s10534-011-9473-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nies DH. The cobalt, zinc, and cadmium efflux system CzcABC from Alcaligenes eutrophus functions as a cation-proton antiporter in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:2707–2712. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2707-2712.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nies DH. Microbial heavy-metal resistance. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999;51:730–750. doi: 10.1007/s002530051457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosen BP. Families of arsenic transporters. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:207–212. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(99)01494-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Páez-Espino D, Tamames J, de Lorenzo V, Canovás D. Microbial responses to environmental arsenic. Biometals. 2009;22:117–130. doi: 10.1007/s10534-008-9195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watling HR, Perrot FA, Shiers DW. Comparison of selected characteristics of Sulfobacillus species and review of their occurrence in acidic and bioleaching environments. Hydrometallurgy. 2008;93:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.hydromet.2008.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Navarro CA, von Bernath D, Jerez CA. Heavy metal resistance strategies of acidophilic bacteria and their acquisition: importance for biomining and bioremediation. Biol. Res. 2013;46:363–371. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602013000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dopson M, Holmes D. Metal resistance in acidophilic microorganisms and its significance for biotechnologies. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;98:8133–8144. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5982-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orell A, Navarro CA, Arancibia R, Mobarec JC, Jerez CA. Life in blue: Copper resistance mechanisms of bacteria and archaea used in industrial biomining of minerals. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010;28:839–848. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orell, A., Remonsellez, F., Arancibia, R. & Jerez, C. A. Molecular characterization of copper and cadmium resistance determinants in the biomining thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus metallicus. Archaea289236, 10.1155/2013/289236 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Dopson M, Ossandon FJ, Lövgren L, Holmes DS. Metal resistance or tolerance? Acidophiles confront high metal loads via both abiotic and biotic mechanisms. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:157. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Navarro CA, Orellana LH, Mauriaca C, Jerez CA. Transcriptional and functional studies of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans genes related to survival in the presence of copper. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:6102–6109. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00308-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Orellana LH, Jerez CA. A genomic island provides Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 53993 additional copper resistance: a possible competitive advantage. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011;92:761–767. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3494-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu X, et al. Metal resistance-related genes are differently expressed in response to copper and zinc ion in six Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans strains. Curr. Microbiol. 2014;69:775–784. doi: 10.1007/s00284-014-0652-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Almárcegui RJ, et al. Response to copper of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 grown in elemental sulfur. Res. Microbiol. 2014;165:761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salazar C, et al. Analysis of gene expression in response to copper stress in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans strain D2, isolated from a copper bioleaching operation. Adv. Mat. Res. 2013;825:157–161. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baker-Austin C, et al. Molecular insight into extreme copper resistance in the extremophilic archaeon ‘ Ferroplasma acidarmanus’ Fer1. Microbiology. 2005;151:2637–2646. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mangold S, Potrykus J, Björn E, Lövgren L, Dopson M. Extreme zinc tolerance in acidophilic microorganisms from the bacterial and archaeal domains. Extremophiles. 2013;17:75–85. doi: 10.1007/s00792-012-0495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alvarez S, Jerez CA. Copper ions stimulate polyphosphate degradation and phosphate efflux in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:5177–5182. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.9.5177-5182.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Remonsellez F, Orell A, Jerez CA. Copper tolerance of the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus metallicus: possible role of polyphosphate metabolism. Microbiology. 2006;152:59–66. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Orell A, Navarro CA, Rivero M, Aguilar JS, Jerez CA. Inorganic polyphosphates in extremophiles and their possible functions. Extremophiles. 2012;16:573–583. doi: 10.1007/s00792-012-0457-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rivero, M. et al. Inorganic polyphosphate, exopolyphosphate, and Pho-84-like transporters may be involved in copper resistance mechanism in Metallosphaera sedula DSM 5348T. Archaea5251061, 10.1155/2018/5251061 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Rao NN, Gómez-García MR, Kornberg A. Inorganic polyphosphate: essential for growth and survival. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:605–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.083007.093039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vera M, Guiliani N, Jerez CA. Proteomic and genomic analysis of the phosphate starvation response of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Hydrometallurgy. 2003;71:125–132. doi: 10.1016/S0304-386X(03)00148-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.You XY, et al. Unraveling the Acidithiobacillus caldus complete genome and its central metabolisms for carbon assimilation. J. Genet. Genomics. 2011;38:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.González C, et al. Genetic variability of psychrotolerant Acidithiobacillus ferrivorans revealed by (meta)genomic analysis. Res. Microbiol. 2014;165:726–734. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu T, et al. CsoR is a novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis copper-sensing transcriptional regulator. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:60–68. doi: 10.1038/nchembio844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rensing C, Fan B, Sharma R, Mitra B, Rosen BP. CopA: An Escherichia coli Cu(I)-translocating P-type ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:652–656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jordan IK, Natale DA, Galperin MY. Copper chaperones in bacteria: association with copper-transporting ATPases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:480–481. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01662-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Navarro CA, von Bernath D, Martínez-Bussenius C, Castillo RA, Jerez CA. Cytoplasmic CopZ-Like protein and periplasmic rusticyanin and AcoP proteins as possible copper resistance determinants in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 23270. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;82:1015–1022. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02810-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zakharchuk LM, et al. Activity of the enzymes of carbon metabolism in Sulfobacillus sibiricus under various conditions of cultivation. Microbiology. 2003;72:553–557. doi: 10.1023/A:1026039132408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krasil’nikova EN, Tsaplina IA, Zakharchuk LM, Bogdanova TI. Effects of exogenous factors on enzymes of carbon metabolism in thermoacidophilic bacteria of the genus Sulfobacillus. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2001;37:358–362. doi: 10.1023/A:1010289618564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kornberg HL, Krebs HA. Synthesis of cell constituents from C2-units by a modified tricarboxylic acid cycle. Nature. 1957;179:988–991. doi: 10.1038/179988a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cronan JE, Jr., Laporte D. Tricarboxylic acid cycle and glyoxylate bypass. EcoSal Plus. 2005 doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.3.5.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Textor S, et al. Propionate oxidation in Escherichia coli: evidence for operation of a methylcitrate cycle in bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 1997;168:428–436. doi: 10.1007/s002030050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Catenazzi MC, et al. A large genomic island allows Neisseria meningitidis to utilize propionic acid, with implications for colonization of the human nasopharynx. Mol. Microbiol. 2014;93:346–355. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Muñoz-Elías EJ, Upton AM, Cherian J, McKinney JD. Role of the methylcitrate cycle in Mycobacterium tuberculosis metabolism, intracellular growth, and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;60:1109–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dolan SK, et al. Loving the poison: the methylcitrate cycle and bacterial pathogenesis. Microbiology. 2018;164:251–259. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yuan T, et al. Heterologous expression of a gene encoding a thermostable β-galactosidase from Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008;30:343–348. doi: 10.1007/s10529-007-9551-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barr DW, Ingledew WJ, Norris PR. Respiratory chain components of iron-oxidizing acidophilic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1990;70:85–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb03781.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blake RC, II, Shute EA, Greenwood MM, Spencer GH, Ingledew WJ. Enzymes of aerobic respiration on iron. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1993;11:9–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1993.tb00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dinarieva TY, Zhuravleva AE, Pavlenko OA, Tsaplina IA, Netrusov AI. Ferrous iron oxidation in moderately thermophilic acidophile Sulfobacillus sibiricus N1(T) Can. J. Microbiol. 2010;56:803–808. doi: 10.1139/W10-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Blake RC, II, et al. In situ spectroscopy reveals that microorganisms in different phyla use different electron transfer biomolecules to respire aerobically on soluble iron. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1963. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Christel S, et al. Weak iron oxidation by Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans maintains a favorable redox potential for chalcopyrite bioleaching. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:3059. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yarzábal A, Duquesne K, Bonnefoy V. Rusticyanin gene expression of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 33020 in sulfur- and in ferrous iron media. Hydrometallurgy. 2003;71:107–114. doi: 10.1016/S0304-386X(03)00146-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]