Abstract

Background

Prevalence estimates of the use of tobacco, alcohol, illegal drugs, and psychoactive medications and of substance-related disorders enable an assessment of the effects of substance use on health and society.

Methods

The data used for this study were derived from the 2018 Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (Epidemiologischer Suchtsurvey, ESA). The sample of the German adult population comprised 9267 persons aged 18 to 64 (response rate, 42%). Population estimates were obtained by extrapolation to a total resident population of 51 544 494 people.

Results

In the 30 days prior to the survey, 71.6% of the respondents (corresponding to 36.9 million persons in the population) had consumed alcohol, and 28.0% (14.4 million) had consumed tobacco. 4.0% reported having used e-cigarettes, and 0.8% reported having used heat-not-burn products. Among illegal drugs, cannabis was the most commonly used, with a 12-month prevalence of 7.1% (3.7 million), followed by amphetamines (1.2%; 619 000). The prevalence of the use of analgesics without a prescription (31.4%) was markedly higher than that of the use of prescribed analgesics (17.5%, 26.0 million); however, analgesics were taken daily less commonly than other types of medication. 13.5% of the sample (7.0 million) had at least one dependence diagnosis (12-month prevalence).

Conclusion

Substance use and the consumption of psychoactive medications are widespread in the German population. Substance-related disorders are a major burden to society, with legal substances causing greater burden than illegal substances.

Substance use is associated with a multitude of health and social effects. The results of the Global Burden of Disease Study clearly demonstrate that alcohol and tobacco use are among the main risk factors worldwide for premature mortality and life years lost due to disease and disability (1, 2). In 2015, every third person in Western Europe reported at least one episode of heavy drinking (= 60 g ethanol) in the preceding 30 days, every fifth person smoked tobacco daily, and 7% of respondents stated that they had consumed cannabis in the previous 12 months (3). Prevalence rates for the use of other illegal drugs such as amphetamines (0.6%), cocaine (1.1%), and opioids (0.4%) were much lower (3).

The consumption of psychoactive substances is associated with an increased risk for substance disorders. The number of individuals with a substance-related dependence per 100 000 people was estimated to be 881 for alcohol and 425 for cannabis in Western Europe in 2015. The number of deaths caused by substance use was reported to be 78 for tobacco, 19 for alcohol, and seven for illegal drugs per 100 000 people in the population (3).

The Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (Epidemiologischer Suchtsurvey, ESA) yields population-representative data on the prevalence of legal and illegal substance use, hazardous forms of use, as well as substance-related disorders according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). Projected prevalence estimates for various indicators of use make it possible to quantify the current burden caused by substance use and substance-related disorders.

Methods

Study design and sample

The 2018 ESA study population is made up of German-speaking individuals aged between 18 and 64 years living in private households in Germany. The sample was drawn in a two-stage selection process. In a first step, 254 municipalities (sample points) were randomly selected. In a second step, addresses were drawn from the respective population registers using a systematic random selection. Data was collected by means of written and online questionnaires or telephone interviews (mixed-method design). The adjusted sample included 9267 individuals (response rate = 41.6%). See the eMethods section for a detailed description of the methods used (mode effects, non-response analyses).

Instruments

Tobacco, e-products, and heat-not-burn products

Prevalence estimates for the use of traditional tobacco products, such as cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, and pipes, water pipes (hookahs), e-cigarettes, e-hookahs, e-pipes, e-cigars, and heat-not-burn products (tobacco heaters), are based on the preceding 30 days (4). Daily cigarette consumption is defined as daily use of at least one cigarette and heavy cigarette consumption as daily use of at least 20 cigarettes (30-day prevalence).

Alcohol

Prevalence estimates of alcohol consumption in the preceding 30 days were made using a beverage-specific quantity–frequency index. Episodic heavy drinking was defined as the consumption of five or more glasses of alcohol (approximately 70 g pure alcohol) on at least one day in the preceding 30 days. The daily consumption of more than 12 g (women) and 24 g (men) of pure alcohol was defined as the threshold for hazardous alcohol consumption (5, 6).

Illegals drugs

The 12-month prevalence for the use of illegal drugs was assessed for cannabis (hashish, marijuana), amphetamine and methamphetamine, ecstasy, LSD, heroin, other opiates, cocaine/crack cocaine, hallucinogenic mushrooms, and new psychoactive substances (NPS).

Medicines

The prevalence values for the use of medicines in the preceding 30 days, as well as their daily use, were recorded for analgesics, hypnotics or sedatives, analeptics, anorectics, antidepressants, and neuroleptics. Respondents allocated each medication they had taken to one of the categories in a list of the most common types of preparations.

Substance-related disorders

Abuse and dependence were recorded as substance-related disorders according to DSM-IV (7) criteria for the use of alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine, analgesics, as well as hypnotics and sedatives. The items in the Munich Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) were used for the purposes of classification. Dependence is the only diagnosis defined for tobacco.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data on substance use in the form of prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals are presented separately for the total population, as well as for men and women. In order to align the data with the distribution of the adult German population, all analyses were weighted (according to age, sex, education level, federal state, and municipality size class). The population size of 51 544 494 people (26 149 029 men; 25 395 465 women) as of 31.12.2017 was used for simple projections by extrapolation to the resident population aged between 18 and 64 years (10). Due to the complex sample design, standard errors were estimated using Taylor series (e1). All analyses were performed using Stata 14.1 (Stata Corp LP; College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Tobacco, e-products, and heat-not-burn products

The prevalence of use of traditional tobacco products within the preceding 30 days was 23.3% (12.0 million individuals) and the prevalence of daily tobacco use was 15.1% (7.8 million individuals) (table 1). Of the tobacco users, 23.4% (2.8 million) reported smoking more than 20 cigarettes a day. The prevalence of water pipe smoking was 4.2% (2.2 million individuals). In all, 4.0% (2.1 million individuals) reported using e-cigarettes and 0.8% (412 000 individuals) heat-not-burn products. Higher prevalence rates were seen among men compared to women across all three product categories.

Table 1. The 30-day prevalence of the use of tobacco, electronic-inhalation and heat-not-burn products, and the use of water pipes (hookahs), as well as projections to the 18- to 64-year old population.

| Tobacco | Men*4 | Women*4 | Total*4 | Projection*5*6 | |||||||

| n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | N | [95% CI] | |

| Cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, pipe | 959 | 26.4 | [24.5; 28.3] | 911 | 20.2 | [18.8; 21.7] | 1870 | 23.3 | [22.1; 24.6] | 12.0 Million | [11.4; 12.7] |

| – Daily use*1 | 524 | 17.0 | [15.3; 18.9] | 519 | 13.1 | [11.9; 14.5] | 1043 | 15.1 | [14.0; 16.3] | 7.8 Million | [7.2; 8.4] |

| – Heavy use*2, consumers | 179 | 29.6 | [25.3; 34.4] | 110 | 15.4 | [12.6; 18.7] | 289 | 23.4 | [20.6; 26.4] | 2.8 Million | [2.3; 3.3] |

| Water pipe (hookah) | 351 | 5.8 | [4.9; 6.7] | 217 | 2.7 | [2.3; 3.1] | 568 | 4.2 | [3.8; 4.8] | 2.2 Million | [2.0; 2.5] |

| e-Cigarette, e-hookah, e-pipe, e-cigar | 240 | 5.7 | [4.8; 6.8] | 120 | 2.2 | [1.8; 2.8] | 360 | 4.0 | [3.5; 4.6] | 2.1 Million | [1.8; 2.4] |

| Heat-not-burn products | 66 | 1.3 | [0.9; 1.8] | 15 | 0.3 | [0.2; 0.5] | 81 | 0.8 | [0.6; 1.1] | 412 | [309; 567] |

| At least one tobacco product*3 | 1247 | 32.5 | [30.5; 34.7] | 1092 | 23.2 | [21.7; 24.8] | 2339 | 28.0 | [26.6; 29.4] | 14.4 Million | [13.7; 15.1] |

*1Daily use of at least one cigarette; *2daily use of at least 20 cigarettes among cigarette users;

*3used cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, pipes, hookah, e-cigarettes, e-hookah, e-pipes, e-cigars, or heat-not-burn products at least once in the preceding 30 days;

*4n, unweighted number; %, weighted prevalence [95% confidence interval]; *5mean based on 51 544 494 people aged between 18 and 64 years (as of 31 December 2017, German Federal Statistical Office);

*6in thousands, except millions. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Alcohol

A total of 71.6% of respondents (36.9 million individuals) stated that they had consumed alcohol in the preceding 30 days (table 2). Of those that had consumed alcohol, 34.5% reported at least one episode of heavy drinking, with the prevalence for men (42.8%) being higher compared to women (24.6%). The prevalence of alcohol use in hazardous quantities was 18.1%, whereby there was no statistically significant difference between the prevalence among men (16.7%) and that among women (19.7%).

Table 2. The 30-day prevalence of alcohol use, as well as projections to the 18- to 64-year-old population.

| Alcohol | Men*3 | Women*3 | Total*3 | Projection*4. *5 | |||||||

| n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | N | [95% CI] | |

| Prevalence of use | 3296 | 76.5 | [74.6; 78.4] | 3563 | 66.5 | [64.7; 68.2] | 6859 | 71.6 | [70.2; 72.9] | 36.9 Million | [36.2; 37.6] |

| Episodic heavy drinking*1, consumers | 1512 | 42.8 | [40.2; 45.3] | 976 | 24.6 | [22.8; 26.6] | 2488 | 34.5 | [32.8; 36.3] | 12.7 Million | [11.9; 13.6] |

| Consumption of hazardous quantities*2, consumers | 598 | 16.7 | [15.1; 18.4] | 718 | 19.7 | [18.2; 21.3] | 1316 | 18.1 | [16.9; 19.3] | 6.7 Million | [6.1; 7.3] |

*1Episodic heavy drinking: consumption of five or more alcoholic beverages on at least one of the preceding 30 days; *2hazardous consumption: average consumption of more than 12 g (women) or 24 g (men) of pure alcohol per day; *3n, unweighted number; % = weighted prevalence [95% confidence interval]; *4mean based on 51 544 494 individuals aged between 18 and 64 years (as of 31 December 2017, German Federal Statistical Office); *5 in millions95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Illegal drugs

With a 12-month prevalence of 7.1% (3.7 million individuals), cannabis was the most frequently used illegal drug, followed by amphetamine at 1.2% (619 000 individuals) (table 3). The use of cocaine/crack cocaine and ecstasy was each reported by 1.1% of respondents. Methamphetamine had the lowest prevalence at 0.2%. Sex differences in substance use were largely not statistically significant—only for cannabis and illegal drugs in general was consumption higher among men compared to women.

Table 3. The 12-month prevalence of illegal drug use, as well as projections to the 18- to 64-year-old population.

| Illegal drugs | Men*2 | Women*2 | Total*2 | Projection*3. *4 | |||||||

| n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | N | [95% CI] | |

| Cannabis | 517 | 8.9 | [8.0; 10.0] | 392 | 5.3 | [4.6; 6.1] | 909 | 7.1 | [6.5; 7.8] | 3.7 Million | [3.4; 4.0] |

| Amphetamine/methamphetamine | 64 | 1.5 | [1.1; 2.1] | 60 | 0.9 | [0.7; 1.3] | 124 | 1.2 | [0.9; 1.6] | 619 | [464; 825] |

| Amphetamine | 64 | 1.5 | [1.1; 2.1] | 60 | 0.9 | [0.7; 1.3] | 124 | 1.2 | [0.9; 1.6] | 619 | [464; 825] |

| Methamphetamine | 7 | 0.3 | [0.1; 0.9] | 3 | 0.1 | [0.0; 0.3] | 10 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.5] | 103 | [52; 258] |

| Ecstasy | 60 | 1.2 | [0.8; 1.6] | 63 | 1.0 | [0.7; 1.3] | 123 | 1.1 | [0.8; 1.4] | 567 | [412; 722] |

| LSD | 29 | 0.5 | [0.3; 0.8] | 10 | 0.1 | [0.1; 0.3] | 39 | 0.3 | [0.2; 0.5] | 155 | [103; 258] |

| Heroin/other opiates | 27 | 0.5 | [0.3; 0.8] | 16 | 0.4 | [0.2; 0.8] | 43 | 0.4 | [0.3; 0.7] | 206 | [155; 361] |

| Cocaine/crack cocaine | 57 | 1.4 | [1.0; 2.0] | 50 | 0.8 | [0.6; 1.2] | 107 | 1.1 | [0.8; 1.5] | 567 | [412; 773] |

| Hallucinogenic mushrooms | 30 | 0.6 | [0.3; 0.9] | 15 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.4] | 45 | 0.4 | [0.3; 0.6] | 206 | [155; 309] |

| New psychoactive substances | 41 | 1.1 | [0.6; 1.8] | 40 | 0.8 | [0.5; 1.2] | 81 | 0.9 | [0.7; 1.3] | 464 | [361; 670] |

| At least one drug*1 | 557 | 10.2 | [9.1; 11.3] | 435 | 6.4 | [5.6; 7.3] | 992 | 8.3 | [7.6; 9.1] | 4.3 Million | [3.9; 4.7] |

*1Cannabis, amphetamines, methamphetamine, ecstasy, LSD, heroin/other opiates, cocaine/crack cocaine, hallucinogenic mushrooms, and new psychoactive substances (NPS); *2n, unweighted number; %, weighted prevalence [95% confidence interval];

*3mean based on 51 544 494 people aged between 18 and 64 years (as of 31.12.2017, German Federal Statistical Office); *4in thousands, except millions; 95% CI; 95% confidence interval

Medicines

In the 30 days prior to the survey, prescription (17.5%; 9.0 million) as well as over-the-counter analgesics (31.4%; 16.2 million individuals) were the most commonly used medicines, with significantly higher prevalence rates among women than among men (table 4). Antidepressants were the second most frequently used prescription medicines at 4.1% (2.1 million individuals). Of the over-the-counter medicines, hypnotics and sedatives (2.0%; 1.0 million individuals) were the second most commonly used. If prescribed by a physician, women took antidepressants significantly more frequently than men. The percentages for the daily use of prescription antidepressants (87.7%) and neuroleptic agents (78.0%) were the highest. The daily use of non-prescription medications was significantly lower.

Table 4. The 30-day prevalence of medicine use and daily use, as well as projections to the 18- to 64-year-old population.

| Medicine | Medicine prescribed by a physician | Medicine not prescribed by a physician | |||||||||||

| Men*2 | Women*2 | Total*2 | Men*2 | Women*2 | Total*2 | Projection*3. *4. *5 | |||||||

| n | % [95% CI] | n | % [95% CI] | n | % [95% CI] | n | % [95% CI] | n | % [95% CI] | n | % [95% CI] | N [95% CI] | |

| Prevalence of use | |||||||||||||

| Analgesics | 535 | 15.2 [13.7; 16.9] | 906 | 20 [18.4; 21.7] | 1441 | 17.5 [16.3; 18.8] | 1035 | 26 [24.3; 27.9] | 1884 | 37.1 [35.4; 38.9] | 2919 | 31.4 [30.2; 32.7] | 26.0 [25.3; 26.7]*5 |

| Hypnotics or sedatives | 68 | 2.2 [1.6; 3.0] | 111 | 2.2 [1.7; 2.9] | 179 | 2.2 [1.8; 2.7] | 83 | 1.8 [1.3; 2.4] | 126 | 2.3 [1.8; 2.8] | 209 | 2.0 [1.7; 2.4] | 2.3 [2.1; 2.7]*5 |

| Analeptics | 17 | 0.6 [0.3; 1.3] | 8 | 0.2 [0.1; 0.4] | 25 | 0.4 [0.2; 0.7] | 37 | 0.6 [0.4; 0.9] | 25 | 0.3 [0.2; 0.4] | 62 | 0.4 [0.3; 0.6] | 464 [309; 619]*4 |

| Anorectics | 2 | 0.0 [0.0; 0.1] | 1 | 0.0 [0.0; 0.1] | 3 | 0.0 [0.0; 0.1] | 4 | 0.1 [0.0; 0.2] | 15 | 0.2 [0.1; 0.5] | 19 | 0.1 [0.1; 0.3] | 103 [52; 155]*4 |

| Antidepressants | 122 | 3.2 [2.5; 4.1] | 210 | 5.0 [4.3; 5.8] | 332 | 4.1 [3.6; 4.7] | 4 | 0.1 [0.0; 0.4] | 1 | 0.0 [0.0; 0.1] | 5 | 0.1 [0.0; 0.2] | 2.2 [1.9; 2.5]*5 |

| Neuroleptics | 29 | 1.0 [0.6; 1.7] | 47 | 1.0 [0.7; 1.5] | 76 | 1.0 [0.8; 1.4] | 2 | 0.0 [0.0; 0.1] | 0 | – | 2 | 0.0 [0.0; 0.1] | 515 [412; 722]*4 |

| Daily use*1 | |||||||||||||

| Analgesics | 97 | 8.0 [6.3; 10.2] | 155 | 6.5 [5.2; 8.0] | 252 | 7.2 [6.1; 8.4] | 7 | 0.5 [0.2; 1.2] | 11 | 0.3 [0.2; 0.6] | 18 | 0.4 [0.2; 0.7] | 1.9 [1.6; 2.2] *5 |

| Hypnotics or sedatives | 28 | 28.3 [18.9; 40.0] | 27 | 15.3 [9.9; 22.8] | 55 | 21.4 [15.9; 28.3] | 5 | 1.7 [0.7; 4.3] | 7 | 3.2 [1.4;7.2] | 12 | 2.5 [1.3; 4.6] | 543 [371; 801]*4 |

| Analeptics | 7 | 23.9 [6.9; 56.9] | 5 | 19.1 [5.7; 48.1] | 12 | 22.6 [8.6; 47.7] | 7 | 11.2 [3.8; 28.5] | 3 | 9.3 [2.6; 28.1] | 10 | 10.7 [4.6; 23.1] | 144 [49; 320]*4 |

| Anorectics | 1 | 16.2 [0.8; 81.7] | 0 | – | 1 | 4.1 [0.5; 28.1] | 0 | – | 4 | 30.9 [7.8; 70.5] | 4 | 23 [5.9; 58.7] | 26 [4; 88]*4 |

| Antidepressants | 108 | 85.8 [75.2; 92.4] | 191 | 89 [82.2; 93.5] | 299 | 87.7 [81.9; 91.9] | 3 | 3.1 [0.7; 12.0] | 0 | – | 3 | 1.3 [0.3; 5.1] | 1.9 [1.6; 2.3]*5 |

| Neuroleptics | 26 | 80.4 [48.0; 94.8] | 35 | 75.6 [57.1; 87.8] | 61 | 78.0 [61.7; 88.7] | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | 398 [252; 635]*5 |

*1In relation to: users of the respective medication group; *2 n, unweighted number; %, weighted prevalence [95% confidence interval]; *3 mean based on 51 544 494 individuals aged between 18 and 64 years for the 30-day prevalence of prescribed and ?non-prescribed medicines (as of 31 December 2017, German Federal Statistical Office); *4 in thousands; *5 in millions; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Substance-related disorders

With a 12-month prevalence of 8.6% (4.4 million individuals), tobacco dependence as defined in DSM-IV was the most common substance-related disorder, followed by analgesic (3.2%; 1.6 million individuals) and alcohol dependence (3.1%; 1.6 million individuals) (table 5). The prevalence rates for dependence on illegal drugs as well as hypnotics/sedatives were both under 1.0%. The percentage for analgesic abuse was highest at 7.6%, followed by alcohol abuse at 2.8%. With the exception of analgesic dependence (men: 2.7%; women: 3.6%), substance-related disorders were more common in men compared to women.

Table 5. The 12-month prevalence of substance-related disorders according to DSM-IV, as well as projections to the 18- to 64-year-old population.

| Disorder according to DSM-IV | Men*1 | Women*1 | Total*1 | Projection*2. 3 | ||||||||

| n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | N | [95% CI] | ||

| Tobacoo | – Dependence | 306 | 9.8 | [8.5; 11.3] | 291 | 7.3 | [6.3; 8.4] | 597 | 8.6 | [7.8; 9.5] | 4.4 Million | [4.0; 4.9] |

| Alcohol | – Abuse | 189 | 4.0 | [3.3; 4.9] | 94 | 1.5 | [1.1; 2.0] | 283 | 2.8 | [2.4; 3.3] | 1.4 Million | [1.2; 1.7] |

| – Dependence | 232 | 4.5 | [3.7; 5.3] | 131 | 1.7 | [1.4; 2.1] | 363 | 3.1 | [2.7; 3.6] | 1.6 Million | [1.4; 1.9] | |

| Cannabis | – Abuse | 41 | 0.7 | [0.5; 1.1] | 24 | 0.4 | [0.2; 0.6] | 65 | 0.5 | [0.4; 0.7] | 309 | [206; 361] |

| – Dependence | 43 | 1.0 | [0.6; 1.5] | 20 | 0.3 | [0.2; 0.5] | 63 | 0.6 | [0.4; 0.9] | 309 | [206; 464] | |

| Cocaine | – Abuse | 5 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.6] | 1 | 0.0 | [0.0; 0.1] | 6 | 0.1 | [0.0; 0.3] | 57 | [21; 144] |

| – Dependence | 5 | 0.1 | [0.0; 0.3] | 3 | 0.0 | [0.0; 0.2] | 8 | 0.1 | [0.0; 0.2] | 41 | [21; 88] | |

| Amphetamines | – Abuse | 5 | 0.1 | [0.1; 0.5] | 5 | 0.1 | [0.0; 0.2] | 10 | 0.1 | [0.0; 0.3] | 57 | [21; 149] |

| – Dependence | 7 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.5] | 10 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.4] | 17 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.4] | 103 | [52; 206] | |

| Analgesics | – Abuse | 274 | 7.9 | [6.9; 9.2] | 374 | 7.2 | [6.4; 8.1] | 648 | 7.6 | [6.9; 8.4] | 3.9 Million | [3.6; 4.3] |

| – Dependence | 77 | 2.7 | [2.0; 3.8] | 146 | 3.6 | [2.9; 4.4] | 223 | 3.2 | [2.7; 3.7] | 1.6 Million | [1.4; 2.0] | |

| Hypnotics or sedatives | – Abuse | 25 | 0.8 | [0.5; 1.2] | 30 | 0.5 | [0.3; 0.8] | 55 | 0.7 | [0.5; 0.9] | 361 | [258; 464] |

| – Dependence | 24 | 0.9 | [0.5; 1.5] | 30 | 0.6 | [0.4; 0.9] | 55 | 0.7 | [0.5; 1.1] | 361 | [258; 567] | |

*1n, Unweighted number; %, weighted prevalence [95% confidence interval]; *2mean based on 51 544 494 individuals aged between 18 and 64 years (as of 31 December 2017, German Federal Statistical Office); *3in thousands, except millions; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

In all, 13.5% of respondents exhibited at least one of the dependence disorders shown in Table 5, which corresponds to 7.0 million 18- to 64-year-olds in the population. Excluding tobacco dependence, 6.7% of respondents, or 3.5 million individuals, qualified for a dependence disorder (data not shown).

Discussion

Tobacco

With 14.4 million current smokers, tobacco use is widespread in Germany. As such, the percentage of current smokers in Germany is significantly higher compared to Belgium, the Netherlands, Great Britain, Ireland, Denmark, Sweden, and Finland, with a prevalence that holds a mid-position among European Union countries (11). Tobacco use is associated with significant risks for cancer as well as cardiovascular, respiratory, and vascular diseases (12, 13, e2). The total number of tobacco-related deaths in Germany in 2013 was estimated at 121 000, with more deaths among men (85 000) compared to women (36 000) (12). Based on the 2018 ESA data, one can assume that 4.4 million of 18- to 64-year-olds in Germany are tobacco-dependent.

Although the use of electronic inhalation products has increased in Germany (14– 16), the prevalence rates for e-cigarette and heat-not-burn product use are still low at 4.0% and 0.8%, respectively. The DEBRA study reported similar rates for e-cigarette use (17, 18). Since the aerosol produced by e-cigarettes contains fewer harmful substances than the smoke from traditional tobacco cigarettes, e-cigarette use is associated with fewer health risks for smokers (19). However, studies on the long-term health effects of e-cigarettes are still lacking. E-cigarettes are often used for smoking cessation and are therefore primarily used by smokers (14, 18, 20, e3). An analysis of ESA data from 2015 showed that 11% of smokers were able to quit with the help of e-cigarettes (14). However, a number of studies suggest that the use of e-cigarettes increases the risk among former smokers and non-smokers, in particular adolescents, of (re-)starting the use of traditional combustible tobacco products (19, 21, e4, e5).

Alcohol

In international comparisons, Germany is one of the high-consumption countries with a pro capita consumption of 10.7 liters of pure alcohol (3), which leads to high alcohol-related morbidity and mortality (22). While heavy alcohol consumption increases the long-term risk for a number of non-communicable diseases, e.g., cardiovascular diseases and cancer (23), episodic heavy drinking is a risk factor for acute effects such as falls or traffic accidents, as well as irreversible damage to the brain and nervous system (24– 26). Moreover, third parties may suffer injury, e.g., due to alcohol consumption during pregnancy or as a result of traffic accidents. For example, the annual number of children born with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) in Germany is estimated to be 12 650, and 45.1% of all third-party deaths in traffic accidents (e.g., pedestrians) can be causally attributed to alcohol consumption (27). The present study revealed approximately 3.1% of respondents to be alcohol-dependent, which corresponds to 1.6 million individuals in the population. The annual economic cost of alcohol consumption in Germany is estimated at 26.7 billion Euro, compared to the far lower tax revenues from the alcohol tax of 3.2 billion Euro (28, 29, e6).

Illegal drugs

In an international comparison, the 12-month prevalence of cannabis use in Germany of 7.1% is in line with the total European average (30). Cannabis dependence was found in 0.6% of study participants. Prescription of cannabis medication by physicans was legalized in Germany in 2017. Against the backdrop of the current political debate on regulation, a recent study emphasizes the fact that the health risks of cannabis consumption should not be underestimated (31). For example, there is a link between cannabis use and the development of anxiety disorders and depression, and there is also an increased risk for the re-emergence of bipolar symptoms (e7, e8). Furthermore, the marked increase in the concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in recent years is accompanied by incalculable health risks (32).

At 1.2%, the prevalence of amphetamine use in Germany was more than twice the European total (0.5%) (30). Interestingly, the prevalence for new psychoactive substances (NPS) (0.9%) is higher than for methamphetamine (0.2%). A regional comparison also shows that methamphetamine use was statistically significantly more widespread in Saxony, Thuringia, and Bavaria in 2015 compared to other German federal states, whereas NPS use was almost evenly distributed across federal states (33). The higher methamphetamine prevalence in the regions close to the Czech Republic has been confirmed by recent wastewater analyses. Compared to other cities investigated in the study, Dresden has the highest inhabitant-specific load (34).

Medicines

In order for medicines to confer a therapeutic benefit, they need to be used as prescribed and not over a long time period (35, 36). This applies not only to addictive analgesics, but also to over-the-counter non-opioid analgesics, for instance. Incorrect use over a longer period of time (= 15 days/month) can cause medication-overuse headache and promote the use of further painkillers, thereby in turn increasing the likelihood for developing medication abuse or dependence (36). Projections put the number of analgesic-dependent 18- to 64-year-olds at 1.6 million. Analyses using the ESA data from 2015, which make a distinction between opioid and non-opioid analgesics, estimated the prevalence of opioid analgesic use disorders according to DSM-V at 1% and the percentage of all mental disorders caused by analgesics at 12% (37). According to the available evidence, the majority of analgesic dependence disorders can be attributed to non-opioid analgesics that were obtained either by private prescriptions or as pharmacy-only medications. This share can be explained by the high prevalence of use combined with the psychological dependence potential of non-opioid analgesics (36). The prevalence of hypnotic/sedative use (30 days) in the population is much lower than that for analgesics, which is reflected in the lower prevalence of dependence disorders.

The vast majority of antidepressants and neuroleptic agents used were prescribed by a physician (population prevalence). The clearly low figures for the daily use of almost all medicines not prescribed by a physician suggests that abuse of these medication groups, with the exception of analgesics, is rare. With regard to analgesics, the high concordance between the population estimate on daily use (1.9 million individuals) and the estimate on analgesic dependence (1.6 million individuals) clearly demonstrates the high dependence potential of these medications.

Limitations

By virtue of its multi-method design, complex sample, and suitable sample size, the 2018 Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse yields reliable, population-representative data on the general adult population aged 18–64 years. Biases may be caused by the systematic non-participation of certain user groups (38). For example, non-responders who filled in the non-response-questionnaire more often exhibited problematic consumption patterns, such as episodic heavy drinking, compared to study participants, but had a lower prevalence for overall consumption (eMethods). Therefore, consumption prevalence is likely to be overestimated and the prevalence of problematic consumption patterns underestimated. Limitations also arise from the fact that the responses of those questioned differ according to the survey method used, and that the estimates are based on self-reported information (38, 39, e9). When interpreting the results, one must bear in mind that the present study design precluded the possibility of reaching population groups such as homeless individuals or prison inmates in whom higher prevalence rates for substance use and substance-related disorders are assumed (40). Consequently, the fact that certain subgroups are inaccessible increases the underestimation of reported prevalence rates on substance use with increasing subgroup marginalization.

Conclusion

In summary, the results of this study indicate that substance use and hazardous consumption patterns are widespread in the general German population and that substance-related disorders, particularly due to legal substances such as tobacco and alcohol, as well as over-the-counter analgesics, represent a considerable burden on society.

Supplementary Material

eMETHODS

Study design and sampling

The population studied in the 2018 Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (ESA) 2018 includes German-speaking people aged between 18 and 64 years (born between 1954 and 2000) living in private households, and covers approximately 51.5 million individuals (German Federal Statistical Office, as of 31. 12. 2017). Sample selection was performed in two stages: first, municipalities (sample points) and then individuals living in these sample points were randomly selected. Municipalities were drawn on the basis of municipal data from the German Federal Statistical Office as well as regional statistical offices. These data were stratified into 10 cells by municipality size category. The distribution of government districts and federal states was taken into account when randomly drawing the municipalities from within the stratified cells. Due to their population size, cities can be represented with several sample points. A total of 254 sample points were drawn.

The target individuals in the sample points were drawn on the basis of population registers using systematic random selection. In order to calculate the requisite initial sample, a minimum targeted sample size of n = 8000 completed surveys was taken as a basis. It was assumed that 50% of the selected individuals would not participate in the survey and approximately 20% would not belong to the study population, since they either did not speak German, did not belong to the age group, or the address was unknown. Therefore, 80 addresses needed to be drawn per sample point, corresponding to an initial sample size of n = 25,158. Due to the uneven distribution of birth cohorts in the study population, younger cohorts, which were not as strongly represented in the study population as older cohorts, were selected more frequently and older cohorts less frequently (disproportionate sampling).

Fieldwork implementation

Fieldwork was carried out by the infas Institute for Applied Social Sciences between March and August 2018. The survey was conducted using written and online questionnaires as well as telephone interviews. The initial sample was divided into a telephone arm and a written arm depending on whether a telephone number could be determined for the respective address. All selected individuals received written correspondence comprising study information, a data privacy statement, an online access code, and an accompanying letter from the German Federal Ministry of Health. They were given the choice of arranging an appointment for an interview or filling out the questionnaire, either in writing or online. The questionnaire could be answered on a variety of mobile devices, such as smartphones or tablets.

The individuals in the telephone arm were informed in the initial correspondence that they would be contacted by telephone. Interviews were conducted by trained telephone interviewers. In those cases where telephone contact was unsuccessful, the written questionnaire was sent by post and the online access code once again provided. Individuals in the written study arm also received the written questionnaire with the initial correspondence. If questionnaires were unreturned, two written reminders were sent with a four-week interval. However, anyone in the written study arm could take part in a telephone interview.

Instruments

The aim of the survey was to record physical and mental health status, dietary behavior, use of tobacco, alcohol, illegal substances, and psychoactive medications, as well as mental disorders and disorders associated with the above-mentioned substances. The survey also recorded a wide range of sociodemographic data (for the questionnaire, see www.esa-survey.de/studie/instrumente.html).

Sociodemography

Sociodemographic characteristics were recorded in line with the demographic standards of the German Federal Statistical Office (e10). In addition to sex and year of birth, data was also recorded on migrant background (country of birth and nationality of the respondents and their parents), family situation (marital status, pregnancy, children, size of household), religious affiliation, education (school education, vocational training), employment (employment status, occupational status), and net household income.

Health and health-related behavior

General health status was recorded using two five-point ratings on physical and mental health (response category 1, “very good” to 5, “very bad”). Furthermore, respondents were asked to state whether they suffered from one or more chronic diseases and whether they had ever been medically diagnosed with a neurological disorder.

Dietary behavior was surveyed using the short form of the “food list” (Lebensmittelliste, LML) (e11). The LML-6 records the frequency of consumption of healthy foods according to the recommendations of the German Nutrition Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung, DGE). Participants were also asked about their physical activities, such as recreational or occupational activities, as well as their views on health risks related to excessive alcohol consumption, such as heart disease, diabetes, overweight, and cancer.

To screen for mental disorders, 11 screening questions from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) were used (e12). The questions related to the presence of psychosomatic symptoms, anxiety disorders (panic, general anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, fear of public places), depression, mania, and post-traumatic stress disorders. Respondents were also asked whether they had ever received psychological, psychiatric, or psychotherapeutic treatment.

Substance use

30-day, 12-month, and lifetime prevalence was recorded for each of the substances listed below.

Tobacco use

The use of cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, pipes, and water pipes (hookahs), as well as e-cigarettes, e-cigars, e-pipes, e-hookahs, and tobacco heaters (heat-not-burn products) was recorded. To determine consumption quantities, respondents were asked about the number of days of use (within the preceding 30 days). For traditional tobacco products such as cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, and pipes, they were additionally asked about the average quantity consumed per day of use.

Alcohol use

The average quantity of alcohol consumed was recorded using a quantity–frequency index separately for beer, wine/sparkling wine, spirits, and alcoholic mixed drinks. Participants were asked to give the number of days (within the preceding 30 days) on which each beverage had been consumed, as well as the number of units of each beverage consumed on a typical day of use. The total volume of pure alcohol consumed (in grams) and an average daily volume was calculated from their responses. To convert liters per beverage into grams of pure alcohol, beverage-specific alcohol contents were used for beer (4.8 vol %), wine/sparkling wine (11.0 vol %), and spirits (33.0 vol %), which corresponds to alcohol volumes of 38.1 g, 87.3 g, and 262.0 g, respectively, of pure alcohol per liter (e13). The estimated average alcohol content of a glass (0.3–0.4 l) of an alcoholic mixed drink was put at 0.04 L of spirits. Individual drinking behavior was divided into five categories using recommended daily tolerable upper alcohol intake levels for low-risk alcohol consumption (e14, e15):

Occasional heavy alcohol consumption (episodic heavy drinking) was recorded by the frequency with which five or more glasses of alcohol (approximately 14 g pure alcohol per glass, i.e., 70 g pure alcohol or more) were consumed on one day, using the following response categories:

Participants that had not consumed alcohol for some time were questioned about their reasons for abstaining and asked to select their response from seven possible reasons why people abstain from alcohol. Using a five-point Likert scale, participants were also asked to evaluate the importance of their stated motives for the decision not to consume alcohol.

Illegal drug use

The prevalence and frequency of use of illegal drugs was recorded for cannabis (hashish, marijuana), amphetamine and methamphetamine, ecstasy, LSD, heroin, other opiates (e.g., codeine, methadone, opium, morphine), cocaine/crack cocaine, inhalants, hallucinogenic mushrooms, and new psychoactive substances (NPS).

Medication use

The prevalence and frequency of use of psychoactive drugs such as analgesics, hypnotics, sedatives, analeptics, anorectics, antidepressants, neuroleptics, and anabolics were surveyed with the following response categories:

Respondents allocated each medication they had taken to one of the categories in a list of the most common types of preparations.

Substance-related disorders

The criteria for substance-related disorders due to alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine, analgesics, hypnotics, and sedatives were recorded using the written version of the Munich Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) for the preceding 12-month period (e12, e16). Dependence according to DSM-IV is present if at least three of seven criteria have been met in the preceding 12 months. In relation to cannabis, three of six criteria need to be met, since the DSM-IV does not define a withdrawal syndrome. For substance abuse, at least one of four criteria needs to be met without dependence on the respective substance being present (e17). There is no abuse diagnosis for tobacco. The items to record substance-related disorders were only given to those respondents that had reported use of the respective substance or relevant medication in the preceding 12 months.

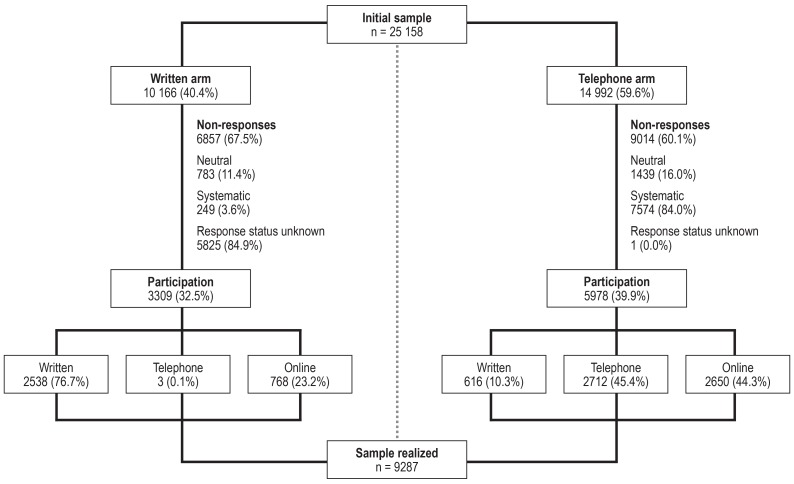

The realized sample

Of the n = 25 158 individuals in the initial sample, 40.4% (n = 10 166) were in the written and 59.6% (n = 14 992) in the telephone arm of the study. While 67.5% in the written study arm did not participate, this was the case for 60.1% in the telephone study arm. With regard to participants in the written study arm, 76.7% used the written questionnaire, 23.2% the online questionnaire, and only 0.1% answered the questionnaire on the telephone. In the telephone study arm, 45.4% preferred the telephone, with only a small percentage (44.3%) favoring the online questionnaire, while 10.3% used the written questionnaire. In total, n = 9287 individuals (realized sample) took part in the survey (efigure).

Response rate

The response rate denotes the ratio of the number of realized cases to the initial sample, whereby this needs to be adjusted for those cases that have no systematic effect on sample selection. These include “person unknown,” “invalid telephone number,” “person does not speak German,” “person does not fulfill the selection criteria,” or “person deceased” (neutral non-response: 8.8%). This proportion was somewhat higher in the telephone study arm (9.6%) compared to the written study arm (7.7%). The percentages on which the calculations of the response rate are based are shown in eTable 1 for both study arms: evaluable questionnaires (36.8%), response status unknown (23.2%), and systematic non-response (31.1%). The latter relates to individuals that were available in principle for the study, but did not participate, i.e., they explicitly declined to participate, were not available during the fieldwork period, could not be questioned due to health problems, failed to return the questionnaire or complete it online despite notification, or failed to keep a telephone appointment. The percentage of systematic non-response was significantly higher in the telephone study arm compared to the written study arm (50.6 % versus 2.5%), with the majority of cases falling into the categories “declined” and “unavailable.” In addition, of the 9287 surveys conducted as part of data validation, 20 cases (0.1%) had to be excluded, meaning that the study sample consisted of altogether n = 9267.

The unknown percentage of neutral non-responses in the group of people whose response status is unknown is estimated as the percentage of neutral non-response (n = 2222) within the number of persons with a known response status (initial sample: n = 25 158 minus number with unknown response status: n = 5826; yields n = 19 332), resulting in a percentage of 11.5%. Thus the initial sample is reduced by the number of neutral non-responses as well as by the estimated number of neutral non-responses among the number of people with no response status (11.5% of 5826 = 670), meaning that the adjusted initial sample is reduced to n = 22 266 individuals (25 158 – 2222 – 670). The response rate for the evaluable cases (n = 9267) from the adjusted initial sample (n = 22 266) is 41.6%.

Weighting

The aim of the 2018 ESA is to make representative statements on the German population aged between 18 and 64 years. To adjust the realized sample to the distribution of central characteristics in the study population, three weights were calculated: a design weight, a post-stratification weight for cross-sectional analysis, and a post-stratification weight for trend analysis. The design weight adjusts for the disproportionate drawing of the sample according to birth cohorts. This weighting factor, which is inversely proportional to the selection probability, is calculated for each of the respective selection stages and takes a minimum value of 0.44 and a maximum of 1.89. To evaluate the effect of weighting, an effective case number was calculated and the effectiveness measure E derived from this (e18, e19). The effectiveness measure of the design weight of 84.3% means that the effective case number in the study sample is reduced from 9267 to 7657.

The post-stratification weights are calculated on the basis of an iterative proportional fitting algorithm (e20). In addition to the design weight, the marginal distributions of the external characteristics federal state, district size, sex, and highest school-leaving qualification in the 18- to 64-year-old population from the 2017 microcensus (e21) were used. Due to the inclusion of additional external weighting variables, the weight necessarily has a greater impact on the effective case number compared to the design weight. With an effectiveness measure of 59.2%, weighting reduces the study sample for cross-sectional analysis to 5381 cases. The weighting factor range is between 0.14 and 8.78.

The adjustment characteristic highest school-leaving qualification was dispensed with for trend analyses, since it could not be included in weighting in surveys up to 2009. With an effective case number of 7387, this weighting factor achieves an effectiveness of 81.3%. The range is between 0.25 and 3.41.

Mode effects

The selection of a particular survey mode depends on a variety of individual characteristics. For example, the percentage of men among online respondents was higher (56.6%) compared to telephone (51.5%) and written respondents (55.9%). Individuals that took part in the study by telephone were older (M = 45.3 years) compared to those who took part in writing (M = 38.2 years) and online (M = 41.0 years). Furthermore, significantly more people that had gained a general qualification for university entrance took part in the online survey (50.0%) than in the written (39.8%) and telephone survey mode (27.6%).

Even when controlling for individual characteristics, which influence the choice of survey mode, there were a number of statistically significant differences between modes (etable 2). Online respondents had a lower prevalence of tobacco and cannabis use compared to individuals that completed the written questionnaire. Likewise, the number of cannabis users among telephone respondents was lower compared to written respondents. Furthermore, the prevalence of alcohol consumption among telephone respondents was lower compared with the written mode, whereas the prevalence of episodic heavy drinking was higher.

Non-response effects

In the non-response survey, differences were seen in substance use between participants and non-participants (etable 3). Individuals that did not take part in the main study consumed statistically significantly less alcohol in the 30 days prior to the survey and had a lower lifetime prevalence in relation to cannabis than did study participants. Non-participants used less cannabis and fewer analgesics in the preceding 12 months. In contrast to this, almost twice as many non-participants as participants reported having consumed five or more glasses of alcohol at least once in the preceding 30 days (episodic heavy drinking). Non-participants also reported having taken hypnotics more frequently in the preceding 12 months compared to participants.

Representativity

The aim of the Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse is to provide population-representative estimates of the use of psychoactive substances and problematic consumption patterns in the general adult population in Germany. The use of different survey methods and weighting of data ensures that analyses are representative for the whole population in terms of distribution according to federal state, size of municipality (according to the German system for classifying municipalities), sex, birth cohort, and school education.

The total number of participants achieved by the 2018 ESA was 9267, hence the desired sample size. This represents a net coverage of 41.6 %, which, although a decline in response rate compared to the previous survey (2015: 52.2%), is nevertheless comparable to other population studies. The Study on Adult Health in Germany (DEGS1) also achieved a response rate of 42% of individuals invited to participate for the first time (e22).

Compared to the previous ESA survey in 2015, it is also noteworthy that the percentage of systematic non-response rose in the telephone study arm (50.6% versus 39.4%), i.e., more target people declined to participate in the study. This has a negative effect on the response rate. In addition, more in-field addresses needed to be drawn in order to achieve the targeted sample size of at least 8000 individuals (25 000 versus 20 000). Analysis of the mode effects also showed that different groups of people favored certain survey methods and that response behavior varies between modes even when controlled for sociodemographic variables.

Although the higher prevalence rates among participants compared to non-participants of socially undesirable behavior, such as episodic heavy drinking, might be explained by socially desirable response behavior, the higher prevalence rates for alcohol, cannabis, and analgesic use observed in participants do not support this hypothesis. In the setting of a survey on substance use, it is more reasonable to assume that especially those individuals with an interest in the subject will participate in the survey. Given that only 12.7% of all non-participants responded to the non-responder questionnaire, the results are merely indicative and should be interpreted with caution. Overall, one can assume that non-participants create little bias in the present sample and the estimates it yields on largely socially acceptable substances such as alcohol, tobacco, and even cannabis. On the other hand, prevalence values for substances and patterns of consumption predominantly found in groups that are highly unlikely to be reached by surveys are underestimated as these groups become ever more marginalized. These include homeless individuals and prison inmates, as well as subgroups exhibiting high and excessive consumption behavior.

Lifelong abstinence

Abstinent in the preceding 12 months

Abstinent in the preceding 30 days

Low-risk consumption (men: = 24 g, women: = 12 g)

High-risk consumption (men: >24 g, women: >12 g).

Episodic heavy drinking never occurred

1–3 days on which episodic heavy drinking occurred

4 or more days on which episodic heavy drinking occurred

Not used

Less than once a week

Once a week

Several times a week

Daily

Key Messages.

Approximately 75% of the German population consumes alcohol and around 25% smokes tobacco (30-day prevalence).

Analgesics, both prescribed and over-the-counter, have the highest prevalence of use; however, their daily use is less frequent compared to other medications (30-day prevalence).

Projected to the German population as a whole, 7.0 million 18- to 64-year-olds qualify for at least one diagnosis of dependence or abuse according to DSM-IV criteria (for tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine, analgesics, hypnotics, and sedatives). At 4.4 million individuals, tobacco dependence accounts for the largest share among the substance-related disorders (12-month prevalence).

The use of illegal and legal psychoactive substances is widespread in Germany.

The social burden due to the use of legal substances is considerably higher compared to that due to illegal substance use.

eFigure.

Course of data collection and response according to study arm

eTable 1. Response according to study arm, n (%).

| Written | Telephone | Total | |

| Initial sample | 10 166 (100.0) | 14 992 (100.0) | 25 158 (100.0) |

| Evaluable questionnaires after data validation | 3289 (32.3) | 5978 (48.6) | 9267 (36.8) |

| Non-evaluable questionnaires after data validation | 20 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (0.1) |

| Response status unknown | 5825 (57.3) | 1 (0.0) | 5826 (23.2) |

| Neutral non-responses | 783 (7.7) | 1439 (9.6) | 2222 (8.8) |

| – Target person unknown | 764 (7.5) | 227 (1.5) | 991 (3.9) |

| – Telephone number invalid | – | 908 (6.1) | 908 (3.6) |

| – Target person does not speak sufficient German | 8 (0.1) | 145 (1.0) | 153 (0.6) |

| – Target person not in the target group | 6 (0.1) | 140 (0.9) | 146 (0.6) |

| – Target person deceased | 5 (0.0) | 19 (0.1) | 24 (0.1) |

| Systematic non-responses | 249 (2.5) | 7574 (50.6) | 7823 (31.1) |

| – Declined | 119 (1.2) | 3790 (25.3) | 3909 (15.5) |

| – Not available | 118 (1.2) | 2812 (18.8) | 2930 (11.6) |

| – Health problems | 5 (0.0) | 68 (0.5) | 73 (0.3) |

| – Target person wishes to respond* | 7 (0.1) | 904 (6.0) | 911 (3.7) |

*The target person wishes to complete the written questionnaire and send it by post, or complete it online or in a telephone interview

eTable 2. A comparison of consumer variables according to type of survey method, n (%) *1.

| Written | Telephone | Online | |

| n = 3154 | n = 2715 | n = 3418 | |

| Alcohol use | |||

| – 30-Day prevalence | 2291 (71.3) | 1974 (69.5)*3 | 2561 (73.8) |

| – Episodic heavy drinking, preceding 30 days*2 | 823 (33.6) | 704 (34.7)*4 | 954 (35.4) |

| Tobacco use | |||

| – 30-Day prevalence | 731 (27.2) | 568 (24.4) | 563 (18.4)*3 |

| – Average number of cigarettes per day, M (SD)*2 | 11.2 (12.2) | 12.7 (9.9) | 10.3 (8.6) |

| Cannabis use | |||

| – Lifetime prevalence | 1139 (35.1) | 656 (21.0)*3 | 1036 (28.0)*3 |

| – 12-Month prevalence | 421 (10.6) | 177 (4.1)*3 | 306 (6.4)*3 |

| Medication use, preceding 12 months | |||

| – Analgesics | 2176 (70.1) | 1852 (69.1) | 2286 (66.8) |

| – Hypnotics | 179 (6.4) | 113 (3.9) | 147 (4.4) |

*1Logistic and linear regression model adjusted according to age, sex, federal state, school education, and net household income (control variables) * 2 In relation to 30-day consumers; * 3 p <0.01 for comparison with “written”; * 4 p <0.05

eTable 3. A comparison of variables of use according to willingness to participate, n (%)*1.

| Participants | Non-participants*2 | |

| n = 9267 | n = 1204 | |

| Alcohol use | ||

| 30-Day prevalence | 6859 (74.2) | 786 (66.3)*4 |

| Episodic heavy drinking in the preceding 30 days*3 | 2488 (36.6) | 445 (60.4)*4 |

| Tobacco use | ||

| 30-Day prevalence | 1870 (20.2) | 256 (21.7) |

| Average number of cigarettes per day, M (SD)*3 | 9.5 (9.1) | 10.1 (8.5) |

| Cannabis use | ||

| Lifetime prevalence | 2850 (30.8) | 232 (19.4)*4 |

| 12-Month prevalence | 909 (9.8) | 72 (6.0)*4 |

| Medication use in the preceding 12 months | ||

| Analgesics | 6341 (69.0) | 782 (65.5)*5 |

| Hypnotics | 441 (4.8) | 75 (6.3)*5 |

*1Logistic and linear regression model adjusted according to age, sex, federal state, and interview type;

*2individuals that completed the “non-response” questionnaire (12.7% of all non-responders);

*3in relation to 30-day consumers; *4p <0.01 for comparison with “participants”; *5p <0.05 for comparison with “participants”

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Christine Rye.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The 2018 Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (ESA) was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit, BMG) (ref: ZMVI1–2517DSM200). Funding is not subject to conditions.

References

- 1.GBD 2017 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1923–1994. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32225-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1659–1724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peacock A, Leung J, Larney S, et al. Global statistics on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use: 2017 status report. Addiction. 2018;113:1905–1926. doi: 10.1111/add.14234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. WHO Press. Geneva: 1998. Guidelines for controlling and monitoring the tobacco epidemic. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burger M, Bronstrup A, Pietrzik K. Derivation of tolerable upper alcohol intake levels in Germany: a systematic review of risks and benefits of moderate alcohol consumption. Prev Med. 2004;39:111–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seitz HK, Bühringer G, Mann K. Deutsche Hauptstelle für Suchtfragen, editor. Grenzwerte für den Konsum alkoholischer Getränke Jahrbuch Sucht 2008. Geesthacht: Neuland. 2008:205–208. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC: 1994. DSM-IV Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wittchen HU, Beloch E, Garczynski E, et al. Max-Planck-Institut für Psychiatrie, Klinisches Institut. München: 1995. Münchener Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI), paper-pencil 22, 2/95. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Statistisches Bundesamt. Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes Deutschland. Ergebnisse auf Grundlage des Zensus 2011. www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsstand/Bevoelkerungsstand.html 2019. (last accessed on 10 January 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Union. Special Eurobarometer 458 “Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes”. http://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/S2146_87_1_458_ENG Directorate-General for Communication 2017 (last accessed on 19 July 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mons U, Kahnert S. Neuberechnung der tabakattributablen Mortalität - Nationale und regionale Daten für Deutschland. Gesundheitswesen. 2019;8:24–33. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-123852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atzendorf J, Gomes de Matos E, Kröger C, Kraus L, Piontek D. Die Nutzung von E-Zigaretten in der deutschen Bevölkerung - Ergebnisse des Epidemiologischen Suchtsurvey 2015. Das Gesundheitswesen. 2019;81:137–143. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-119079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orth B, Merkel C. Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung. Köln: 2018. Rauchen bei Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen in Deutschland Ergebnisse des Alkoholsurveys 2016 und Trends. BZgA-Forschungsbericht. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orth B, Merkel C. Der Rückgang des Zigarettenkonsums Jugendlicher und junger Erwachsener in Deutschland und die zunehmende Bedeutung von Wasserpfeifen, E-Zigaretten und E-Shishas. Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2018;61:1377–1387. doi: 10.1007/s00103-018-2820-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotz D, Kastaun S. E-Zigaretten und Tabakerhitzer: repräsentative Daten zu Konsumverhalten und assoziierten Faktoren in der deutschen Bevölkerung (die DEBRA-Studie) Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2018;61:1407–1414. doi: 10.1007/s00103-018-2827-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotz D, Böckmann M, Kastaun S. The use of tobacco, e-cigarettes, and methods to quit smoking in Germany—a representative study using 6 waves of data over 12 months (the DEBRA study) Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:235–242. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press 2018. www.doi.org/10.17226/24952 (last accessed on 13 March 2019) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahman MA, Hann N, Wilson A, Mnatzaganian G, Worrall-Carter L. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122544. e0122544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutra LM, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarettes and conventional cigarette use among US. adolescents: a cross-sectional study. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:610–617. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.5488. Erratum in: JAMA Pediatr 2014; 168: 684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraus L, Pabst A, Piontek D, et al. Temporal changes in alcohol-related morbidity and mortality in Germany. Eur Addict Res. 2015;21:262–272. doi: 10.1159/000381672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 2018;392:1015–1035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Järvenpää T, Rinne JO, Koskenvuo M, Räihä I, Kaprio J. Binge drinking in midlife and dementia risk. Epidemiology. 2005;16:766–771. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000181307.30826.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valencia-Martín JL, Galán I, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. The joint association of average volume of alcohol and binge drinking with hazardous driving behaviour and traffic crashes. Addiction. 2008;103:749–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mundt MP, Zakletskaia LI, Fleming FM. Extreme college drinking and alcohol-related injury risk. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1532–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00981.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraus L, Seitz NN, Shield KD, Gmel G, Rehm J. Quantifying harms to others due to alcohol consumption in Germany: a register-based study. BMC Medicine. 2019;17:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1290-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaertner B, Freyer-Adam J, Meyer C, John U. Deutsche Hauptstelle für Suchtfragen Alkohol - Zahlen und Fakten zum Konsum Jahrbuch Sucht 2015. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers. 2015:39–71. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams M, Effertz T. Volkswirtschaftliche Kosten des Alkohol- und Tabakkonsums Alkohol und Tabak. Grundlagen und Folgeerkrankungen. In: Singer MV, Batra A, Mann K, editors. Georg Thieme Verlag KG. Stuttgart: 2011. pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 30.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) European Drug Report 2018. Trends and developments. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union 2018. www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/edr/trends-developments/2018_en (last accessed on 19 July 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider M, Friemel CM, von Keller R, et al. Cannabiskonsum zum Freizeitgebrauch Cannabis: Potenzial und Risiko. Eine wissenschaftliche Bestandsaufnahme. In: Hoch E, Friemel CM, Schneider M, editors. Springer. Berlin: 2018. pp. 65–264. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandra S, Radwan MM, Majumdar CG, Church JC, Freeman TP, ElSohly MA. New trends in cannabis potency in USA and Europe during the last decade (2008-2017) Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;269:5–15. doi: 10.1007/s00406-019-00983-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gomes de Matos E, Hannemann TV, Atzendorf J, Kraus L, Piontek D. The consumption of new psychoactive substances and methamphetamine—analysis of data from 6 German federal states. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:49–55. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) Wastewater analysis and drugs—a European multi-city study. www.emcdda.europa.eu/topics/pods/waste-water-analysis (last accessed on 29 March 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glaeske G. Deutsche Hauptstelle für Suchtfragen e. V. (DHS), editor. Medikamente 2016 - Psychotrope und andere Arzneimittel mit Missbrauchs- und Abhängigkeitspotenzial Jahrbuch Sucht 18. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers. 2018:85–104. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soyka M. Schattauer. Stuttgart: 2016. Medikamentenabhängigkeit: Entstehungsbedingungen - Klinik - Therapie. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aydin D. Konsumstörungen im Zusammenhang mit opioidhaltigen und nicht opioidhaltigen Schmerzmitteln - Prävalenz in der Bevölkerung und prädiktive Effekte (Bachelorarbeit) FernUniversität in Hagen. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piontek D, Kraus L, Gomes de Matos E, Atzendorf J. Der Epidemiologische Suchtsurvey 2015: Studiendesign und Methodik. Sucht. 2016;62:259–269. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorber SC, Schofield-Hurwitz S, Hardt J, Levasseur G, Tremblay M. The accuracy of self-reported smoking: a systematic review of the relationship between self-reported and cotinine-assessed smoking status. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:12–24. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fazel S, Khosla V, Doll H, Geddes J. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLOS Medicine. 2008;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225. e225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Heeringa SG, West BT, Berglund PA. Applied survey data analysis 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- E2.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Tobacco smoke and involuntary smoking. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, Vol. 83. Lyon, France 2004. https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/mono83.pdf. (last accessed on 19 July 2019) [Google Scholar]

- E3.Pearson JL, Richardson A, Niaura RS, Vallone DM, Abrams DB. E-cigarette awareness, use, and harm perceptions in US adults. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1758–1766. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Morgenstern M, Nies A, Goecke M, Hanewinkel R. E-cigarettes and the use of conventional cigarettes—a cohort study in 10th grade students in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:243–248. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Schneider S, Diehl K. Vaping as a catalyst for smoking? An initial model on the initiation of electronic cigarette use and the transition to tobacco smoking among adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:647–653. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Effertz T. Peter Lang. Frankfurt am Main: 2015. Die volkswirtschaftlichen Kosten gefährlichen Konsums Eine theoretische und empirische Analyse für Deutschland am Beispiel Alkohol, Tabak und Adipositas. [Google Scholar]

- E7.Hoch E, Schneider M, von Keller R, et al. Wirksamkeit, Verträglichkeit und Sicherheit von medizinischem Cannabis: Potenzial und Risiko. Eine wissenschaftliche Bestandsaufnahme. In: Hoch E, Friemel CM, Schneider M, editors. Springer. Berlin: 2018. pp. 265–426. [Google Scholar]

- E8.Hoch E, Niemann D, von Keller R, et al. How effective and safe is medical cannabis as a treatment of mental disorders? A systematic review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;1:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s00406-019-00984-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Stockwell T, Zhao J, Greenfield T, Li J, Livingston M, Meng Y. Estimating under- and over-reporting of drinking in national surveys of alcohol consumption: identification of consistent biases across four English-speaking countries. Addiction. 2016;111:1203–1213. doi: 10.1111/add.13373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Statistisches Bundesamt. Demographische Standards Ausgabe 2010 Statistik und Wissenschaft. Wiesbaden. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- E11.Keller S. Zur Validität des Transtheoretischen Modells - Eine Untersuchung zur Veränderung des Ernährungsverhaltens Marburg 1998. http://archiv.ub.unimarburg.de/diss/z1998/ 0303/html/ (last accessed on 19 July 2019) [Google Scholar]

- E12.Wittchen HU, Beloch E, Garczynski E, et al. Max-Planck-Institut für Psychiatrie, Klinisches Institut. München: 1995. Münchener Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI), paper-pencil 22, 2/95. [Google Scholar]

- E13.Bühringer G, Augustin R, Bergmann E, et al. Alkoholkonsum und alkoholbezogene Störungen in Deutschland Schriftenreihe des Bundesministeriums für Gesundheit.. Bd. 128. ed. Baden-Baden Nomos. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- E14.Burger M, Bronstrup A, Pietrzik K. Derivation of tolerable upper alcohol intake levels in Germany: a systematic review of risks and benefits of moderate alcohol consumption. Prev Med. 2004;39:111–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Seitz HK, Bühringer G, Mann K, Jahrbuch Sucht 2008 Grenzwerte für den Konsum alkoholischer Getränke Deutsche Hauptstelle für Suchtfragen. Geesthacht: Neuland. 2008:205–208. [Google Scholar]

- E16.Lachner G, Wittchen HU, Perkonigg A, et al. Structure, content and reliability of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) substance use sections. Eur Addict Res. 1998;4:28–41. doi: 10.1159/000018922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Saß H, Wittchen HU, Zaudig M, Houben I. Diagnostische Kriterien DSM-IV. Göttingen: Hogrefe. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- E18.Gabler S, Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik J, Krebs D. Gewichtung in der Umfragepraxis. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- E19.Little RJ, Lewitzky S, Heeringa S, Lepkowski J, Kessler RC. Assessment of weighting methodology for the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:439–449. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Gelman A, Carlin J. Poststratification and weighting adjustments Survey nonresponse. In: Groves RM, Eltinge JL, Little RJA, editors. John Wiley and Sons. New York: 2002. pp. 289–303. [Google Scholar]

- E21.Bundesamt S. Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes Deutschland Ergebnisse auf Grundlage des Zensus. www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungs stand/Bevoelkerungsstand.html2019 (last accessed on 10 January 2019) 2011 [Google Scholar]

- E22.Kamtsiuris P, Lange M, Hoffmann R, et al. Die erste Welle der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1) Stichprobendesign, Response, Gewichtung und Repräsentativität, Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2013;56:620–630. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1650-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMETHODS

Study design and sampling

The population studied in the 2018 Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (ESA) 2018 includes German-speaking people aged between 18 and 64 years (born between 1954 and 2000) living in private households, and covers approximately 51.5 million individuals (German Federal Statistical Office, as of 31. 12. 2017). Sample selection was performed in two stages: first, municipalities (sample points) and then individuals living in these sample points were randomly selected. Municipalities were drawn on the basis of municipal data from the German Federal Statistical Office as well as regional statistical offices. These data were stratified into 10 cells by municipality size category. The distribution of government districts and federal states was taken into account when randomly drawing the municipalities from within the stratified cells. Due to their population size, cities can be represented with several sample points. A total of 254 sample points were drawn.

The target individuals in the sample points were drawn on the basis of population registers using systematic random selection. In order to calculate the requisite initial sample, a minimum targeted sample size of n = 8000 completed surveys was taken as a basis. It was assumed that 50% of the selected individuals would not participate in the survey and approximately 20% would not belong to the study population, since they either did not speak German, did not belong to the age group, or the address was unknown. Therefore, 80 addresses needed to be drawn per sample point, corresponding to an initial sample size of n = 25,158. Due to the uneven distribution of birth cohorts in the study population, younger cohorts, which were not as strongly represented in the study population as older cohorts, were selected more frequently and older cohorts less frequently (disproportionate sampling).

Fieldwork implementation

Fieldwork was carried out by the infas Institute for Applied Social Sciences between March and August 2018. The survey was conducted using written and online questionnaires as well as telephone interviews. The initial sample was divided into a telephone arm and a written arm depending on whether a telephone number could be determined for the respective address. All selected individuals received written correspondence comprising study information, a data privacy statement, an online access code, and an accompanying letter from the German Federal Ministry of Health. They were given the choice of arranging an appointment for an interview or filling out the questionnaire, either in writing or online. The questionnaire could be answered on a variety of mobile devices, such as smartphones or tablets.

The individuals in the telephone arm were informed in the initial correspondence that they would be contacted by telephone. Interviews were conducted by trained telephone interviewers. In those cases where telephone contact was unsuccessful, the written questionnaire was sent by post and the online access code once again provided. Individuals in the written study arm also received the written questionnaire with the initial correspondence. If questionnaires were unreturned, two written reminders were sent with a four-week interval. However, anyone in the written study arm could take part in a telephone interview.

Instruments

The aim of the survey was to record physical and mental health status, dietary behavior, use of tobacco, alcohol, illegal substances, and psychoactive medications, as well as mental disorders and disorders associated with the above-mentioned substances. The survey also recorded a wide range of sociodemographic data (for the questionnaire, see www.esa-survey.de/studie/instrumente.html).

Sociodemography

Sociodemographic characteristics were recorded in line with the demographic standards of the German Federal Statistical Office (e10). In addition to sex and year of birth, data was also recorded on migrant background (country of birth and nationality of the respondents and their parents), family situation (marital status, pregnancy, children, size of household), religious affiliation, education (school education, vocational training), employment (employment status, occupational status), and net household income.

Health and health-related behavior

General health status was recorded using two five-point ratings on physical and mental health (response category 1, “very good” to 5, “very bad”). Furthermore, respondents were asked to state whether they suffered from one or more chronic diseases and whether they had ever been medically diagnosed with a neurological disorder.

Dietary behavior was surveyed using the short form of the “food list” (Lebensmittelliste, LML) (e11). The LML-6 records the frequency of consumption of healthy foods according to the recommendations of the German Nutrition Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung, DGE). Participants were also asked about their physical activities, such as recreational or occupational activities, as well as their views on health risks related to excessive alcohol consumption, such as heart disease, diabetes, overweight, and cancer.

To screen for mental disorders, 11 screening questions from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) were used (e12). The questions related to the presence of psychosomatic symptoms, anxiety disorders (panic, general anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, fear of public places), depression, mania, and post-traumatic stress disorders. Respondents were also asked whether they had ever received psychological, psychiatric, or psychotherapeutic treatment.

Substance use

30-day, 12-month, and lifetime prevalence was recorded for each of the substances listed below.

Tobacco use

The use of cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, pipes, and water pipes (hookahs), as well as e-cigarettes, e-cigars, e-pipes, e-hookahs, and tobacco heaters (heat-not-burn products) was recorded. To determine consumption quantities, respondents were asked about the number of days of use (within the preceding 30 days). For traditional tobacco products such as cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, and pipes, they were additionally asked about the average quantity consumed per day of use.

Alcohol use

The average quantity of alcohol consumed was recorded using a quantity–frequency index separately for beer, wine/sparkling wine, spirits, and alcoholic mixed drinks. Participants were asked to give the number of days (within the preceding 30 days) on which each beverage had been consumed, as well as the number of units of each beverage consumed on a typical day of use. The total volume of pure alcohol consumed (in grams) and an average daily volume was calculated from their responses. To convert liters per beverage into grams of pure alcohol, beverage-specific alcohol contents were used for beer (4.8 vol %), wine/sparkling wine (11.0 vol %), and spirits (33.0 vol %), which corresponds to alcohol volumes of 38.1 g, 87.3 g, and 262.0 g, respectively, of pure alcohol per liter (e13). The estimated average alcohol content of a glass (0.3–0.4 l) of an alcoholic mixed drink was put at 0.04 L of spirits. Individual drinking behavior was divided into five categories using recommended daily tolerable upper alcohol intake levels for low-risk alcohol consumption (e14, e15):

Occasional heavy alcohol consumption (episodic heavy drinking) was recorded by the frequency with which five or more glasses of alcohol (approximately 14 g pure alcohol per glass, i.e., 70 g pure alcohol or more) were consumed on one day, using the following response categories:

Participants that had not consumed alcohol for some time were questioned about their reasons for abstaining and asked to select their response from seven possible reasons why people abstain from alcohol. Using a five-point Likert scale, participants were also asked to evaluate the importance of their stated motives for the decision not to consume alcohol.

Illegal drug use

The prevalence and frequency of use of illegal drugs was recorded for cannabis (hashish, marijuana), amphetamine and methamphetamine, ecstasy, LSD, heroin, other opiates (e.g., codeine, methadone, opium, morphine), cocaine/crack cocaine, inhalants, hallucinogenic mushrooms, and new psychoactive substances (NPS).

Medication use

The prevalence and frequency of use of psychoactive drugs such as analgesics, hypnotics, sedatives, analeptics, anorectics, antidepressants, neuroleptics, and anabolics were surveyed with the following response categories:

Respondents allocated each medication they had taken to one of the categories in a list of the most common types of preparations.

Substance-related disorders