Abstract

Background

Changes in the use of psychoactive substances and medications and in the occurrence of substance-related disorders enable assessment of the magnitude of the anticipated negative consequences for the population.

Methods

Trends were analyzed in the consumption of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis and other illegal drugs, analgesics, and hypnotics/sedatives, as well as trends in substance-related disorders, as coded according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). The data were derived from nine waves of the German Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (Epidemiologischer Suchtsurvey, ESA) from 1995 to 2018. The data were collected in written form or by means of a combination of paper and internet-based questionnaires or telephone interviews.

Results

The estimated prevalence rates of tobacco and alcohol consumption and the use of hypnotics/sedatives decreased over time. On the other hand, increasing prevalence rates were observed for the consumption of cannabis and other illegal drugs and the use of analgesics. The trends in substance-related disorders showed no statistically significant changes compared to the reference values for the year 2018, except for higher prevalence rates of nicotine dependence, alcohol abuse and dependence, analgesic dependence, and hypnotic/sedative dependence in the year 2012 only.

Conclusion

Trends in tobacco and alcohol consumption imply a future decline in the burden to society from the morbidity, mortality, and economic costs related to these substances. An opposite development in cannabis use cannot be excluded. No increase over time was seen in the prevalence of analgesic dependence, but the observed increase in the use of analgesics demands critical attention.

In the years 2006 and 2016, tobacco use was the leading global risk factor for early death and loss of life years due to disability (e1). In 1990, tobacco had occupied third place among 86 comparable risk factors. Alcohol consumption was the fourth most important risk factor in 2016 (fifth in 1990), while illegal drugs were listed in 18th place (21st in 1990). In the USA the prescription of pain-relieving drugs has been debated in connection with the threefold increase in opioid overdoses between 2010 and 2014 (1, 2) and a related decrease in life expectancy (3).

Observations of changes in the use of psychoactive substances and medications and in the occurrence of substance-related disorders enable assessment of the magnitude of the anticipated negative consequences for the population and are thus of wide-reaching importance for health policy (e2). Given the causal connection between use and negative consequences such as illness and death, trends in indicators of consumption permit conclusions regarding the future development of such consequences. In Germany, the Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (Epidemiologischer Suchtsurvey; ESA) has been conducting regular cross-sectional surveys of substance use and related disorders in the adult population (18 to 64 years) since 1995 (4).

The study reported here was designed to analyze:

Trends in use of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and other illegal drugs together with intake of analgesics and hypnotics/sedatives

Trends in substance-related disorders as coded according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV).

Methods

The data came from nine ESA surveys carried out between 1995 and 2018 (every 3 years from 1997 onwards). Owing to changes in the age range surveyed during the observation period, all analyses were restricted to the age range 18 to 59 years. (Information on the individual ESA surveys can be found in the eMethods.) The data were collected in written form or by means of a combination of paper and internet-based questionnaires or telephone interviews. (For details of the complex sampling techniques, see the eMethods.) Information was collected on consumption and patterns of use (amount) of tobacco and alcohol, the use of cannabis, the use of at least one other illegal drug, and the intake of medications (details of the survey instruments are given in the eMethods). Documentation of substance-related disorders was adapted from the Munich Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI, [5, 6]). Diagnoses were assigned according to the criteria of DSM-IV (7).

Sex-specific analyses of the trends in substance use and related disorders were based on binomial logistic regression models. (For details of the statistical analyses, see the eMethods.) With time as predictor, the trend with regard to tendency and course was assessed. A statistical test to ascertain any difference between the sexes was carried out only if men and women showed similar trends. The prevalences, mean predicted prevalences, and 95% confidence intervals for each survey year and sex are shown in the Figures. Analyses of trends in substance-related disorders were performed on the whole sample—with the year 2018 as reference—for the categorical variable survey year. (For sex-specific data and a detailed presentation of the findings, see the eFigures and eTables.) Because of the complexity of the sample design (see the eMethods for details), weights were used in every survey year. These involved, among others, the distribution by federal state, community size, sex, and year of birth across the German population. Standard errors based on Taylor series were calculated to take account of the effects of the multistage selection procedure (8). The level of significance was set at 5%.

Results

The results of the regression models for the trends in substance use are presented in shortened form for the sake of readability. A comprehensive account of the statistical analyses and findings can be found in the eMethods supplement and in the eFigures and eTables.

Tobacco

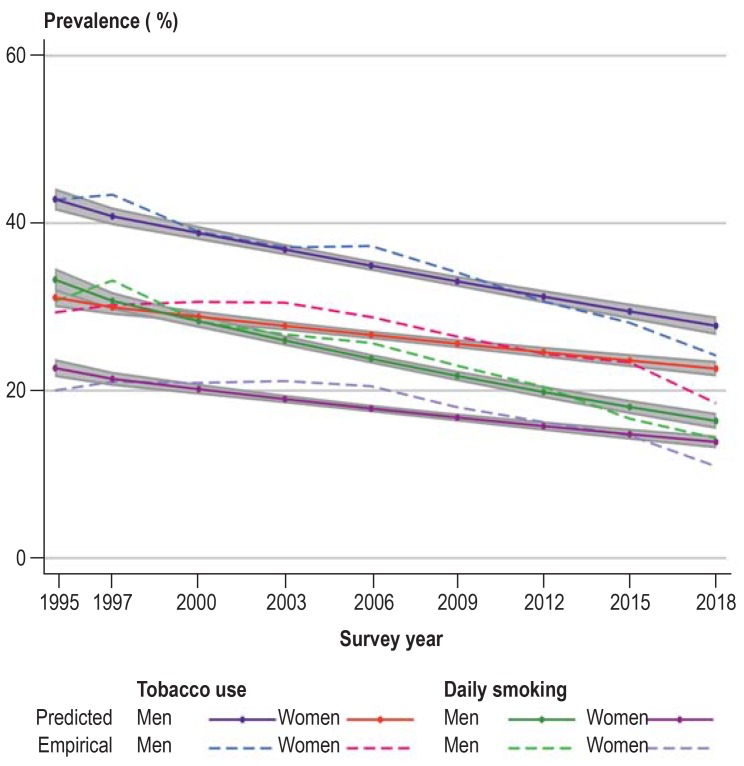

The prevalence of tobacco use shows a decreasing trend in both sexes, more so in women than in men. A comparable trend can be observed for the prevalence of daily smoking by women and men (Figure 1, Table 1).

Figure 1.

Predicted and empirically derived prevalence of tobacco use and daily smoking in the past 30 days by survey year and sex

Table 1. Trends by substance and sex.

| Substance use | Men | Women |

| Tobacco (30 days) | Decreasing*2 | Decreasing*2 |

| Tobacco daily (30 days) | Decreasing*2 | Decreasing*2 |

| Alcohol (30 days) | Decreasing | Decreasing |

| Episodic heavy drinking (30 days) | Decreasing*2 | Increasing*2 |

| Cannabis (12 months) | Increasing*2 | Increasing*2 |

| Other illegal drugs (12 months) | Constant | Increasing |

| Analgesics (30 days. weekly*1) | Increasing | Increasing |

| Hypnotics/sedatives (30 days. weekly*1) | Decreasing | Decreasing |

*1Users of the respective class of drugs

*2Statistically significant difference between men and women. level of significance 5% (with uniform trend)

Alcohol

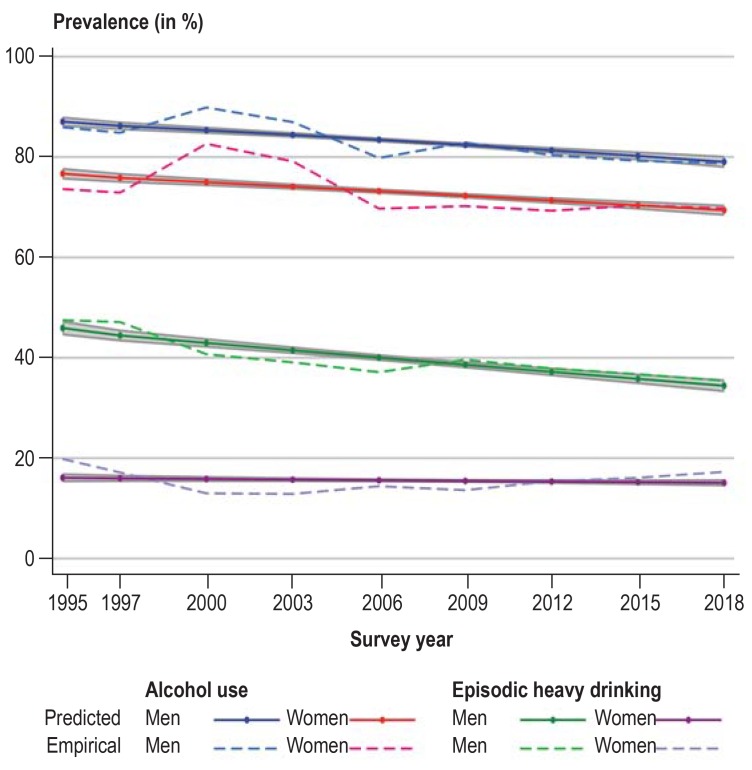

The prevalence of alcohol use shows a decreasing trend in both sexes, more so in women than in men. The prevalence of episodic heavy drinking displays an increasing trend in women but a decreasing trend in men (Figure 2, Table 1).

Figure 2.

Predicted and empirically derived prevalence of alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking in the past 30 days by survey year and sex

Illegal drugs

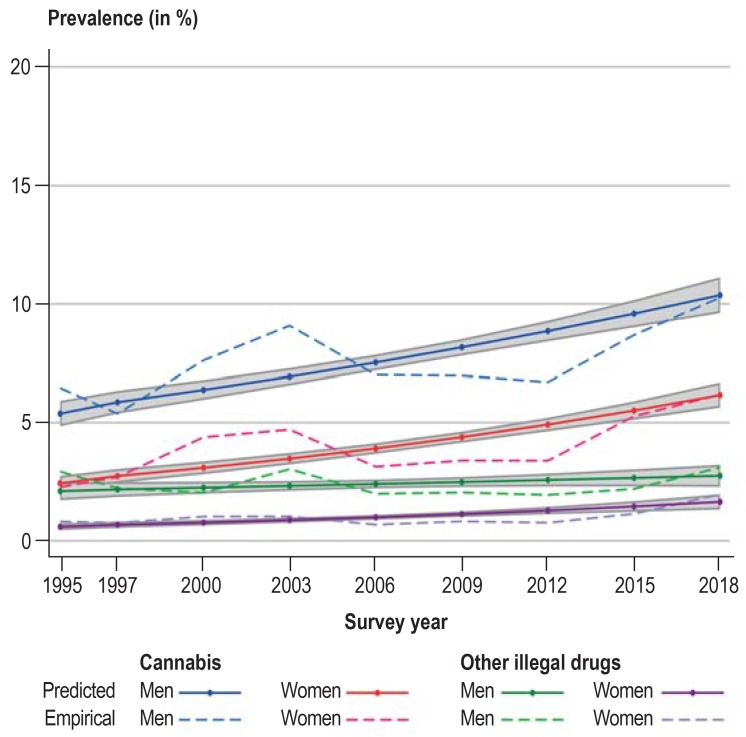

The prevalence of cannabis consumption shows an increasing trend in both sexes, with a tendency towards a higher increase in men than in women. The prevalence of use of at least one other illegal drug (amphetamine/methamphetamine, ecstasy, LSD, heroin/other opiates, or cocaine/crack) is constant in men and increases in women (Figure 3, Table 1).

Figure 3.

Predicted and empirically derived prevalence of use of cannabis and other illegal drugs in the past 12 months by survey year and sex

Medications

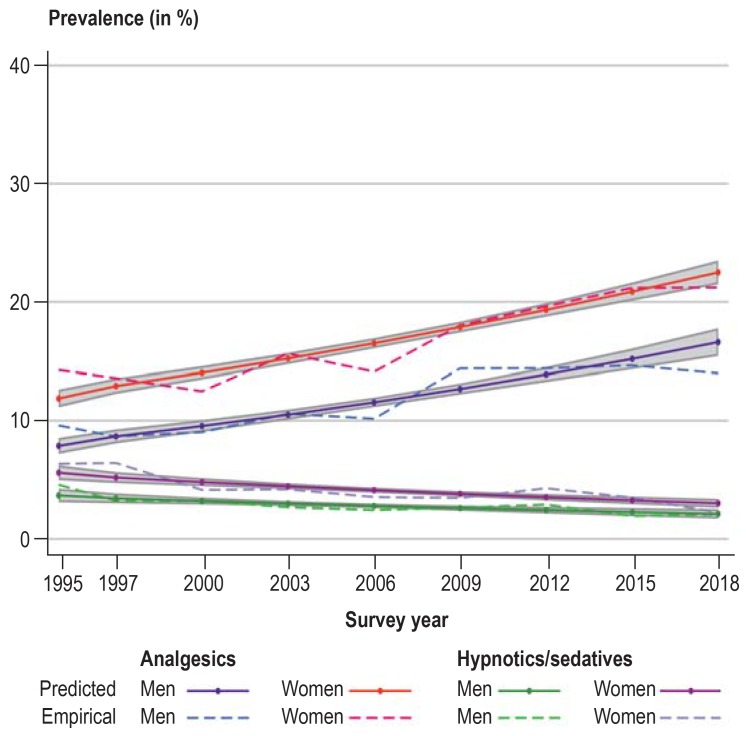

In both men and women the prevalence of weekly intake of analgesics shows an increasing trend and that of hypnotics/sedatives a decreasing trend (Figure 4, Table 1).

Figure 4.

Predicted and empirically derived prevalence of use of analgesics and hypnotics/sedatives in the past 30 days by survey year and sex

Substance-related disorders

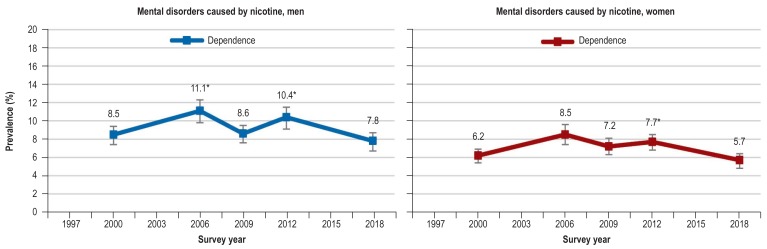

Among the substance-related disorders (table 2), nicotine dependence shows the highest prevalence and the greatest fluctuation over time in both sexes. The prevalence was significantly higher in 2006 (men 11.1%, women 8.5%) and 2012 (men 10.4%, women 7.7%) than in 2018 (men 7.8%, women 5.7%).

Table 2. Trends in substance-related disorders according to DSM-IV for 18- to 59-year-old men and women (12-month prevalence).

| 1997 | 2000 | 2006 | 2009 | 2012 | 2018 | ||

| % [95% CI] | % [95% CI] | % [95% CI] | % [95% CI] | % [95% CI] | % [95% CI] | ||

| Men | |||||||

| Nicotine | Dependence | 8.5 [7.6; 9.6] | 11.1* [9.9; 12.4] | 8.6 [7.7; 9.6] | 10.4* [9.3; 11.7] | 7.8 [6.9; 8.9] | |

| Alcohol | Abuse | 5.4 [4.5; 6.6] | 6.3* [5.4; 7.3] | 5.3* [4.6; 6.2] | 4.0 [3.4; 4.7] | ||

| Dependence | 4.2 [3.4; 5.1] | 4.5 [3.8; 4.8] | 4.0 [3.3; 4.8] | 5.2* [4.4; 6.1] | 4.8 [4.1; 5.5] | ||

| Cannabis | Abuse | 0.7 [0.4; 1.2] | 1.2 [0.9; 1.7] | 0.8 [0.6; 1.2] | 0.7 [0.5; 1.0] | ||

| Dependence | 0.7 [0.4; 1.1] | 0.5* [0.3; 0.8] | 0.7 [0.5; 1.0] | 0.8 [0.5; 1.1] | 0.9 [0.6; 1.3] | ||

| Analgesics | Dependence | 1.8 [1.4; 2.3] | 2.5 [2.0; 3.1] | 1.9 [1.4; 2.5] | |||

| Hypnotics/sedatives | Dependence | 0.9 [0.7; 1.3] | 1.3* [0.9; 1.8] | 0.6 [0.4; 1.0] | |||

| Women | |||||||

| Nicotine | Dependence | 6.2 [5.5; 7.0] | 8.5 [7.4; 9.6] | 7.2 [6.3; 8.1] | 7.7* [6.9; 8.6] | 5.7 [5.0; 6.6] | |

| Alcohol | Abuse | 1.5 [1.0; 2.1] | 1.2 [0.9; 1.7] | 1.8* [1.4; 2.2] | 1.5 [1.2; 1.9] | ||

| Dependence | 1.0 [0.6; 1.4] | 1.2 [0.9; 1.6] | 1.5 [1.2; 2.0] | 2.1*[1.7; 2.5] | 1.9 [1.6; 2.3] | ||

| Cannabis | Abuse | 0.3 [0.2; 0.7] | 0.2 [0.1; 0.4] | 0.2 [0.1; 0.4] | 0.4 [0.3; 0.6] | ||

| Dependence | 0.1 [0.0; 0.4] | 0.2 [0.1; 0.4] | 0.3 [0.2; 0.6] | 0.2 [0.1; 0.4] | 0.3 [0.2; 0.5] | ||

| Analgesics | Dependence | 2.7 [2.3; 3.3] | 3.4* [2.9; 4.1] | 3.1 [2.6; 3.7] | |||

| Hypnotics/sedatives | Dependence | 0.7 [0.5; 0.9] | 1.5* [1.2; 2.0] | 0.5 [0.3; 0.8] | |||

The prevalence rates of substance-related disorders differ slightly from publications in previous years because the coding of some diagnostic criteria was altered.

* p <0.05 for comparison with reference year 2018; logistic regression for prediction of prevalence with year. age. survey method;

95% CI. 95% confidence interval

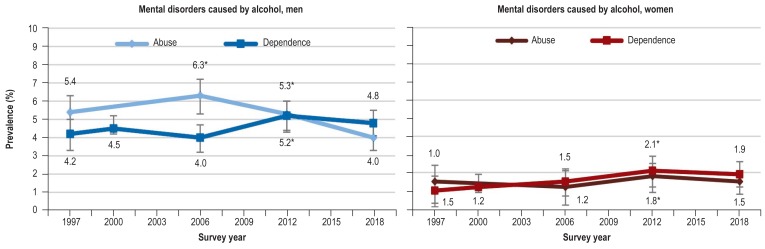

The prevalence of alcohol abuse in men was statistically significantly lower in 2018, at 4.0%, than in 2006 (6.3%) and 2012 (5.3%). The same was true for women comparing 2018 (1.5%) with 2012 (1.8%). The prevalence of alcohol dependence reached a statistically significant peak in 2012 (men 5.2%, women 2.1%) but returned to a level comparable with previous years in 2018.

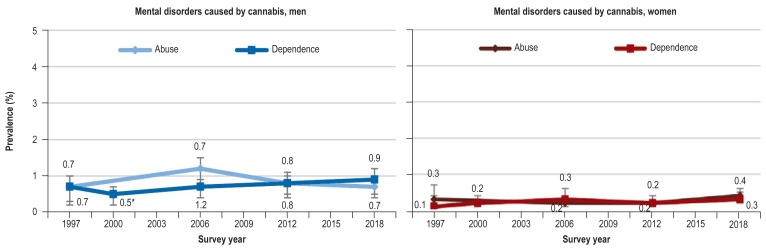

The prevalence of cannabis-related disorders shows a generally constant trend in men, with the exception of the year 2000 (0.5%).

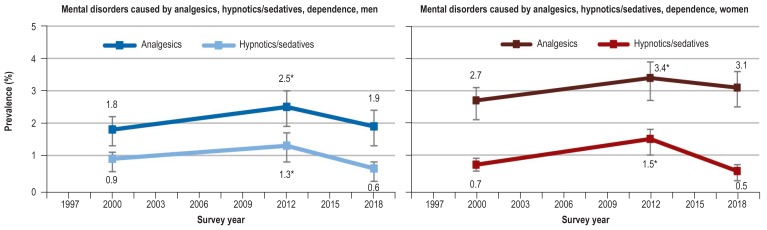

In 2018, the prevalence of analgesic and hypnotic/sedative dependence fell back to the levels in 2000. For both classes of drugs, the prevalence of dependence was higher in 2012 than in 2018 for both men (analgesics 2.5%, hypnotics/sedatives 1.3%) and women (analgesics 3.4%, hypnotics/sedatives 1.5%).

Discussion

Tobacco

The observed distinct decrease in the 30-day prevalence of both tobacco use and daily smoking is confirmed by the findings of studies in adults (9), young adults (10), and adolescents (11). Studies from other European countries and North America also show clear reductions in the prevalence of (daily) smoking (12, 13). However, a recent meta-analysis has shown that the greatest part of the risk for coronary heart disease and stroke is attributable to the use of just a few cigarettes per day, that there is no threshold below which tobacco use is safe, and that the risk can be avoided only by giving up tobacco entirely (e3). When one includes all tobacco, electronic inhalation, and heat-not-burn products, as well as water pipes, the proportion of current smokers in the 18 to 64 age group in Germany is still high, at around 25% (7).

A number of policy measures have been credited with the observed decrease in the prevalence of smoking in Germany (14), for example:

Increased taxation of tobacco

Amendments of the Workplace Ordinance and the German Protection of Young Persons Act

Restriction of tobacco advertising

The passing of the Non-Smokers’ Protection Act in 2007

Introduction of smoking bans in the individual federal states.

However, a considerable time lag can be expected before there are any major effects of decreasing tobacco use on morbidity and mortality, and thus on economic costs (e4).

The question of whether the changes in the prevalence of nicotine dependence between 2012 and 2018 represent a decrease or merely fluctuations around a constant trend cannot be answered at the present moment. Continuation of the positive trend towards reduced tobacco use in Germany will require strict implementation of the measures contained in the WHO Framework Convention and thus restrictive tobacco policies (e5). Prevention of tobacco use by children and adolescents will continue to be key (15, 16), together with expansion of smoking cessation programs (17).

Alcohol

Alongside a slight reduction in the prevalence of alcohol use, a decrease in risky patterns of use in the form of episodic heavy drinking can be observed, at least in men. Alcohol is not only drunk less often, it is also less frequently imbibed in large amounts, and the average consumption has gone down (18). Nevertheless, Germany is still one of the countries where the most alcohol is drunk (19). One reason for this is inconsistent implementation of preventive measures to effectively reduce the availability of alcohol and thus lower the demand (20). The need for the implementation and application of appropriate measures to be at the forefront of evidence-based alcohol policy in Germany has not changed substantially since publication of an analysis in 2008 (21).

Positive trends, however, can be seen with regard to alcohol consumption by adolescents. A number of studies point to a general reduction in adolescents’ alcohol consumption in Germany (22) and especially in other European countries (13), North America (23), and Australia (24). Because behavior in adolescence molds the drinking patterns in later life, this development can be expected to lead to a generation-related reduction in alcohol use as the respective age cohorts grow older (25).

The finding of practically unchanged prevalence of alcohol-related disorders is no surprise. Estimates of the uptake of addiction care services show clearly that overall only 16% of persons with alcohol dependence-related illness seek outpatient or inpatient help, including rehabilitation (26). The aim should therefore be to increase the uptake of professional addiction care services. The major cornerstones of such a campaign are alcohol screening programs and short-term interventions, in primary health care by general practitioners, the efficacy of which has been demonstrated in a number of studies (e6, 27). To avoid negative alcohol-related consequences, it is essential to strengthen efforts to prevent hazardous drinking patterns such as heavy use and binge drinking.

Illegal drugs

In contrast to the decreasing trend in use of legal substances, the use of cannabis, and to a lesser extent the use of at least one other illegal drug, increased during the observation period. However, this trend is not reflected in the prevalence of cannabis-related disorders. The trends in consumption are confirmed in studies of adolescents. For example, the 12-month prevalence and the prevalence of regular use increased in 12- to 17-year-olds. The prevalence of use in the age group 18 to 25 years also increased statistically significantly between 2008 and 2016 (28). An increase in the prevalence of cannabis use by adolescents and young adults is likewise reported for most European countries (29) and for the USA (30). The current debate on recent changes in cannabis legislation in Uruguay (31), some states of the USA (32), and recently in Canada (33) is viewed as a reason for the increase in recent years (34). Changes in the subjective perception of the health risks associated with cannabis use have been discussed as a possible mediating factor. For instance, adult residents of the USA judged cannabis to be less dangerous for health in 2014 than they had done 10 to 15 years earlier (35).

The prevalence of use of at least one other illegal drug is relatively stable, so it can be assumed that the number of persons using other illegal substances has remained largely unchanged over time. Because drug users with intensive patterns of use are very likely to be greatly underrepresented in population surveys, the majority of positive cases are broadly socially integrated occasional consumers (36). It can thus be assumed that the prevalence of illegal drug use is regularly underestimated in surveys. However, evidence of a constant rate of opioid dependence over the past 20 years (37) suggests that the number of high-risk users of illegal hard drugs has also hardly changed.

Medications

Prescription data provide external validation of the trends in medication intake (38). They show that total numbers of prescriptions of opioid analgesics and non-opioid analgesics, in terms of defined daily doses, increased in parallel from 2008 to 2017. A recent study evaluating prescription data from statutory health insurance records shows, however, that the number of persons receiving prescriptions for opioid pain relievers increased only slightly between 2006 and 2016 (e7). The available data on trends in the use of analgesics do not permit separate analysis of opioid- and non-opioid-containing painkillers, because they were not distinguished at all time points. Under the assumption that the proportions of consumed opioid and non-opioid analgesics—including over-the-counter medications—have not changed dramatically over time, the constant prevalence of analgesic dependence indicates that the abuse of opioid painkillers has not increased in general. It can therefore be concluded, from the trends in opioid prescribing, the near-constant numbers of opioid addicts contacting the addiction care services (37), and the minor increase in the numbers of fatal overdoses involving opioids (39), that there is no opioid epidemic in Germany comparable with that in the USA. As for the intake of analgesics, it is important to improve the information supplied to the population and intensify the training of primary care physicians and personnel in medical and geriatric institutions, with regard to the prescription of these drugs.

The decreasing trend in the intake of hypnotics/sedative and the small amount of fluctuation in the numbers of associated dependence disorders point to a possible delayed positive effect. This development is confirmed by a recent study based on an evaluation of prescriptions supplied to statutorily insured patients (40). According to the authors, the numbers of persons receiving prescriptions for benzodiazepines and z-drugs and the numbers of prescriptions that deviate from guidelines are decreasing in the statutorily insured population.

Limitations

Prevalence figures that rely on self-reported data on substance use can be underestimated in cross-sectional analyses due to the influence of socially desired response behavior. If one assumes that the impact of these variables remains constant across repeated cross-sectional analyses, bias introduced by response behavior plays no part in the analysis of trends over time, although the true prevalence is unknown.

Bias may arise from heterogeneity in sampling procedures and in the characteristics of the sample population. However, this bias was minimized by matching the distribution of the sample to the respective characteristics of the general population.

Summary

The decreasing trends in use of tobacco and alcohol are a positive development. To avoid reversal of these trends in the future, steps to promote prevention and early detection are required. An increasing trend in cannabis consumption cannot be excluded, and appropriate preventive measures must be intensified. The prevalence of dependence on analgesics has shown no discernible increase over time. However, the increased use of analgesics should be monitored closely. In general, it can be assumed that effective steps to reduce substance use lead to decreased population-wide burdens in terms of morbidity, mortality, and economic costs.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Details of methods

Study design and samples

The data used for this study came from nine surveys conducted in the course of the Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (ESA) between 1995 and 2018 (every 3rd year from 1997 onwards). The case numbers varied from 7833 (1995) to 9267 (2018); the response rates ranged between 42% (2018) and 65% (1995 and 1997). The change in the upper age limit during the observation period limits the analysis of trends to the age range 18 to 59 years (etable 1).

Weighting

The goal of the ESA is to provide data on substance use representative for the German population between 18 and 59 years (survey years 1995 to 2003) or between 18 and 64 years (survey years 2006 to 2018). In each individual survey, weights were calculated to adjust the distribution of basic sample characteristics to the general population. Since 2006, weights have been determined to compensate for the disproportional composition of the age groups in the sample. These weights are inversely proportional to the likelihood of selection at the respective probability level. Furthermore, the weights accounted for the marginal distributions of the external characteristics federal state, community size, and sex in the 18- to 64-year old population of the microcensus for the survey year concerned. Detailed information on the weighting for the different survey years can be found in the individual source publications (etable 1).

Instruments

Tobacco use

Tobacco use was defined as smoking at least one cigarette, cigar, cigarillo, or pipe in the 30-day period prior to the survey. Daily use was defined as smoking at least one cigarette per day over the preceding 30 days.

Alcohol use

The prevalence of alcohol use relates to the 30-day period preceding the survey. Alcoholic drinks included beer, wine/sparkling wine, and spirits, plus alcopops (in 2006) or mixed drinks containing alcohol (from 2009; e.g., alcopops, long drinks, cocktails, punch). Episodic heavy drinking was defined as consumption of five or more glasses of alcohol (ca. 70 g pure alcohol) in a single day at least once in the preceding 30 days.

Use of illegal drugs

The prevalence of use of cannabis and at least one other illegal drug relates to the 12-month period preceding the survey. Because of the low case numbers, amphetamine/methamphetamine, ecstasy, LSD, heroin/other opiates, cocaine/crack, and hallucinogenic mushrooms were combined into the category “other illegal drugs.”

Medication intake

The survey asked about intake of analgesics and hypnotics/sedatives in the previous 30 days. Weekly use comprised intake at least once per week. The survey participants allocated each medication they had taken to one of the categories in a list of the most common types of preparations.

Substance-related disorders

The documentation of substance-related disorders caused by alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, amphetamine, analgesics, hypnotics, and sedatives was based on the Munich Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI). Disorders occurring in the previous 12 months were classified according to the criteria of DSM-IV and divided into abuse and dependence. Substance-related disorders according to DSM-IV were documented in the individual surveys as follows: nicotine: 2000, 2006, 2009, 2012, 2018; alcohol and cannabis: 1997, 2006, 2012, 2018; analgesics, hypnotics/sedatives: 2000, 2012, 2018.

Statistical analyses

Missing data were partly replaced by means of a logical imputation process. For example, if a filtering question regarding general drug use was answered in the negative the missing data on use of the various substances was replaced with non-use, or a missing value for lifetime use in the presence of a positive response for 12-month use was replaced with a positive response for lifetime prevalence. Moreover, missing data per year were excluded from the regression analyses for trends per substance, which in analogy to the cross section corresponds to pairwise exclusion of persons with missing data.

Sex-specific analyses of the trends in substance use and substance-related disorders are based on binomial logistic regression models. For the dependent variable “substance use,” the survey year was employed in the model as continuous predictor “time” with equidistant intervals. For the dependent variable “substance-related disorders,” the survey year was used as categorical predictor, because disorders were not documented at regular intervals.

Age and survey type were used as control variables in all regression models so that effects of age or survey type could be excluded. On grounds of the complex sample design, the weights for each survey year were included in the statistical analyses. To take account of the multistage selection procedure, standard errors based on Taylor series were calculated using survey-specific statistical methods (8). The level of significance was set at 5%.

Models for substance use

In the models for the trends in substance use, “time” was mean-centered and included as a linear and/or quadratic predictor. Statistically significant regression coefficients indicate linear or curvilinear trends. Negative values of the regression coefficients for linear time bL characterize a falling, positive values a rising tendency. The regression coefficient for quadratic time bQ indicates both the direction and the steepness of the curve in a curvilinear trend. A positive value means that the curve is directed upwards or convex, while a negative value shows that the curve is directed downwards or concave. In a significant curvilinear trend both regression coefficients (linear and quadratic) are considered when interpreting the results.

When the trends were similar in men and women, they were compared between the sexes. In this event, the regression coefficients were compared for the linear or quadratic predictor “time” using a Wald test. Predicted values for each person were calculated on the basis of the models. The mean predicted values, their 95% confidence intervals, and the prevalence by survey year and sex are shown in the Figures in the body of the article. The detailed results of the regression models and data on sample size, prevalence rates, and their estimated mean values and 95% confidence intervals are shown in eTables 2– 13, based on the regression models for each survey year by sex.

Models for substance-related disorders

Analyses of the trends in substance-related disorders were performed for the whole sample, with 2018 as reference year for the categorical variable “survey year” (see analyses of all 18- to 59-year-olds in eTable 14).

Tobacco

The prevalence of tobacco use shows a curvilinear decreasing trend for both sexes (men: bL = -0.088, bQ = -0.005; women: bL = -0.051, bQ = -0.014), with a more pronounced curvature for women than for men (F [1; 3 878] = 7.7; p < 0.01). A comparable trend is seen for the prevalence of daily tobacco use (men: bL = -0.116, bQ = -0.009; women: bL = -0.076, bQ = -0.019; F [1; 3 878] = 6.9; p < 0.01) (eTables 2– 4).

Alcohol

The prevalence of alcohol use shows a linear decreasing trend (bL = -0.072) for men, while a concave decreasing trend is seen for women (bQ = -0.007). The decrease is greater for women than for men. The fluctuations in prevalence were smoothed by the model and the resulting predicted values. The prevalence of episodic heavy drinking displays a convex trend for both men (bQ = 0.007) and women (bQ = 0.024), representing a slightly accelerated increase with a more pronounced curvature for women (F [1; 3 875] = 23.79; p <0.001). Taking into account the values of the linear time coefficients (men: bL = -0.065; women: bL = -0.005), an increasing trend can be assumed only for women (eTables 5– 7).

Illegal drugs

The prevalence of cannabis use shows a linear trend in both sexes. The increase in the proportion of women using cannabis is statistically significantly stronger than in men (men: bL = 0.093, women: bL = 0.132; F[1; 3 877] = 4.88, p <0.05). The prevalence of the use of other illegal drugs is constant in men and increasing linearly in women (bL = 0.120) (eTables 8– 10).

Medications

For men, the prevalence of weekly intake of analgesics is increasing linearly (linear time: bL = 0.107) and that of hypnotics/sedatives is decreasing linearly (linear time: bL = -0.062). Although a generally accelerated convex increase is seen for both indicators in women (analgesics: bQ = 0.011, hypnotics/sedatives: bQ = 0.010), the growth in the prevalence of intake of hypnotics/sedatives is less pronounced, because of the negative coefficients of linear time (bL = -0.082), than is the case for analgesics, where the positive coefficient of linear time (bL = 0.097) accelerates the growth (eTables 11– 13).

Substance-related disorders

Among the substance-related disorders, nicotine dependence shows the highest prevalence and the strongest fluctuations over time (eTable 14, eFigure 1). Compared with 2018 (6.8%), the prevalence was significantly higher in both 2006 (9.8%; t = 3.05; p <0.01) and 2012 (9.1%; t = 3.34; p <0.001).

The prevalence of alcohol abuse was significantly lower in 2018 (2.7%) than in 2006 (3.8%; t = 3.36; p <0.001) and 2012 (3.6%; t = 3.32; p <0.001). After a significant peak in 2012 (3.7%; t=5.24; p <0.001), the prevalence of alcohol dependence in 2018 was comparable with that in earlier years. With the exception of 2012 (0.3%; t = -2.06; p <0.05), the prevalence of cannabis-related disorders shows a generally constant trend.

The prevalence of mental disorders caused by analgesics and hypnotics/sedatives in 2018 fell back to the level in 2000.

Key Messages.

The 30-day prevalence of tobacco use and the prevalence of daily smoking are on the decrease, but steps must be taken to reinforce this positive trend.

There has been a slight decrease in the prevalence of alcohol use; episodic heavy drinking has increased slightly in women.

The prevalence of the use of cannabis and other illegal drugs has increased (the latter in women only).

Analgesics are being taken more frequently, hypnotics/sedatives less frequently.

The current prevalence rates for substance-related disorders are similar to the levels in 1997 or 2000.

eFigure 1.

Trends in substance-related disorders according to DSM-IV for nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, analgesics, and hypnotics/sedatives in men and women

eFigure 2.

eFigure 3.

eFigure 4.

eTable 1. Overview of the individual surveys conducted in the course of the Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse in the period 1995 to 2018.

| Year | N | Age (years) | Response rate | Survey design | Survey type | Reference |

| 2018 | 9267 | 18–64 | 42% | Sample of registered residents. disproportionate sampling, initial contact by post; German-speaking population | Written questionnaire/telephone interview/internet | Atzendorf et al.. 2019 (7) |

| 2015 | 9204 | 18–64 | 52% | Sample of registered residents. disproportionate sampling, initial contact by post; German-speaking population | Written questionnaire/telephone interview/internet | Piontek & Kraus. 2016 (e8) |

| 2012 | 9084 | 18–64 | 54% | Sample of registered residents. disproportionate sampling, initial contact by post; German-speaking population | Written questionnaire/telephone interview/internet | Kraus. Piontek. Pabst & Gomes de Matos. 2013 (e9) |

| 2009 | 8030 | 18–64 | 50% | Sample of registered residents. disproportionate sampling, initial contact by post; German-speaking population | Written questionnaire/telephone interview/internet | Kraus & Pabst. 2010 (e10) |

| 2006 | 7912 | 18–64 | 45% | Sample of registered residents. disproportionate sampling, initial contact by post; German-speaking population | Written questionnaire/telephone interview | Kraus & Baumeister. 2008 (e11) |

| 2003 | 8061 | 18–59 | 55% | Sample of registered residents. disproportionate sampling, initial contact by post; German-speaking population | Written questionnaire | Kraus & Augustin. 2005 (e12) |

| 2000 | 8139 | 18–59 | 51% | Sample of registered residents. age-proportional sampling, postal delivery of questionnaire; German-speaking population | Written questionnaire | Kraus & Augustin. 2001 (e13) |

| 1997 | 8020 | 18–59 | 65% | Random route; ADM design (Bundestag electoral district); age-proportional sampling; personal delivery of questionnaire; German-speaking residential population | Written questionnaire | Kraus & Bauernfeind. 1998 (e14) |

| 1995 | 7833 | 18–59 | 65% | Random route; ADM design (Bundestag electoral district); age-proportional sampling; personal delivery of questionnaire; ‧German-speaking residential population | Written questionnaire | Herbst. Kraus & Scherer. 1996 (e15) |

ADM: Arbeitskreis Deutscher Markt- und Sozialforschungsinstitute e.V. (Association of German Market and Social Research Institutes)

eTable 2. Results of the regression models for tobacco use and daily tobacco use in the past 30 days prior to the survey.

| Tobacco use | Daily tobacco use | |||||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||

| Variables | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE |

| Curvilinear model | ||||||||

| Linear time | – 0.088 | 0,007 | – 0.051 | 0,006 | – 0.116 | 0,008 | – 0.076 | 0,008 |

| Quadratic time | – 0.005*2 | 0,002 | – 0.014*2 | 0,002 | – 0.009*2 | 0,003 | – 0.019*2 | 0,003 |

| Age | – 0.171 | 0,018 | – 0.204 | 0,018 | – 0.047 | 0,02 | – 0.027 | 0,02 |

| Survey method*1 | ||||||||

| Written questionnaire | 0.009 | 0,04 | 0.142 | 0,039 | – 0.086 | 0,046 | – 0.065 | 0,046 |

| Internet-based | – 0.278 | 0,056 | – 0.151 | 0,061 | – 0.428 | 0,069 | – 0.373 | 0,075 |

| Constants | – 0.161 | – 0.530 | – 0.891 | – 1.262 | ||||

| Linear model | ||||||||

| Linear time | – 0.086*2 | 0,007 | – 0.045*2 | 0,006 | – 0.116*2 | 0,008 | – 0.076*2 | 0,008 |

| Age | – 0.171 | 0,018 | – 0.203 | 0,018 | – 0.047 | 0,02 | – 0.027 | 0,02 |

| Survey method*1 | ||||||||

| Written questionnaire | 0.013 | 0,04 | 0.152 | 0,039 | – 0.086 | 0,046 | – 0.065 | 0,046 |

| Internet-based | – 0.304 | 0,054 | – 0.217 | 0,059 | – 0.428 | 0,069 | – 0.373 | 0,075 |

| Constants | – 0.198 | – 0.629 | – 0.891 | – 1.262 | ||||

*1 Reference category: telephone interview; bold type: significant coefficients with level of significance at 5%

*2 Significant difference in coefficients between men and women with level of significance at 5%; b. regression coefficient; SE. standard error

eTable 3. Sample size, prevalence, estimated prevalence with 95% confidence intervals for tobacco use by survey year and sex.

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Survey year | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI |

| 1995 | 3514 | 42,8 | 42,8 | [41.5; 44.2] | 4231 | 29,3 | 31,1 | [30.0; 32.2] |

| 1997 | 3709 | 43,4 | 40,8 | [39.7; 41.9] | 4270 | 30,2 | 30 | [29.0; 30.9] |

| 2000 | 3645 | 39 | 38,8 | [38.0; 39.7] | 4407 | 30,6 | 28,8 | [28.1; 29.5] |

| 2003 | 3582 | 37,1 | 36,8 | [36.2; 37.5] | 4393 | 30,5 | 27,7 | [27.1; 28.3] |

| 2006 | 3074 | 37,3 | 34,9 | [34.3; 35.5] | 3890 | 28,8 | 26,6 | [26.1; 27.2] |

| 2009 | 3224 | 34,1 | 33 | [32.4; 33.7] | 4063 | 26,4 | 25,6 | [25.1; 26.2] |

| 2012 | 3418 | 30,6 | 31,2 | [30.4; 32.0] | 4535 | 24,4 | 24,6 | [23.9; 25.2] |

| 2015 | 3692 | 28,1 | 29,5 | [28.5; 30.4] | 4546 | 23,4 | 23,6 | [22.8; 24.4] |

| 2018 | 3731 | 24,2 | 27,7 | [26.6; 28.9] | 4556 | 18,5 | 22,6 | [21.7; 23.6] |

N. Sample size; Est. prev.. mean estimated prevalence;95% CI. 95% confidence interval

eTable 4. Sample size, prevalence, estimated prevalence with 95% confidence intervals for daily smoking by survey year and sex.

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Survey year | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI |

| 1995 | 3497 | 30,7 | 33,2 | [31.9; 34.6] | 4222 | 20 | 22,7 | [21.6; 23.8] |

| 1997 | 3682 | 33,1 | 30,7 | [29.6; 31.8] | 4246 | 21 | 21,4 | [20.6; 22.3] |

| 2000 | 3610 | 28,3 | 28,3 | [27.5; 29.1] | 4377 | 20,9 | 20,2 | [19.5; 20.8] |

| 2003 | 3529 | 26,7 | 26 | [25.3; 26.6] | 3864 | 21,1 | 19 | [18.5; 19.5] |

| 2006 | 3003 | 25,7 | 23,8 | [23.2; 24.4] | 4048 | 20,5 | 17,9 | [17.4; 18.3] |

| 2009 | 3162 | 23 | 21,7 | [21.1; 22.4] | 4048 | 18 | 16,8 | [16.3; 17.3] |

| 2012 | 3345 | 20,4 | 19,8 | [19.1; 20.6] | 4508 | 16,2 | 15,8 | [15.2; 16.3] |

| 2015 | 3613 | 16,6 | 18 | [17.2; 18.9] | 4526 | 14,6 | 14,8 | [14.1; 15.5] |

| 2018 | 3683 | 14,3 | 16,4 | [15.4; 17.3] | 4539 | 11 | 13,9 | [13.1; 14.6] |

N. Sample size; Est. prev.. mean estimated prevalence;95% CI. 95% confidence interval

eTable 5. Results of the regression models for alcohol use and episodic heavy drinking in the past 30 days prior to the survey.

| Alcohol | Episodic heavy drinking*1 | |||||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||

| Variables | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE |

| Curvilinear model | ||||||||

| Linear time | – 0.072 | 0,01 | – 0.046 | 0,007 | – 0.065 | 0,007 | – 0.005 | 0,007 |

| Quadratic time | – 0.003 | 0,003 | – 0.007 | 0,003 | 0.007*3 | 0,003 | 0.024*3 | 0,003 |

| Age | 0.049 | 0,012 | 0.015 | 0,009 | – 0.161 | 0,009 | – 0.287 | 0,01 |

| Survey method*2 | ||||||||

| Written questionnaire | 0.114 | 0,05 | 0.087 | 0,038 | – 0.093 | 0,042 | – 0.015 | 0,045 |

| Internet-based | 0.026 | 0,059 | 0.113 | 0,053 | – 0.053 | 0,049 | 0.014 | 0,061 |

| Constants | 1.353 | 0.910 | 0.282 | – 0.674 | ||||

| Linear model | ||||||||

| Linear time | – 0.072*3 | 0,01 | – 0.046*3 | 0,007 | – 0.067 | 0,007 | – 0.012 | 0,008 |

| Age | 0.049 | 0,012 | 0.016 | 0,009 | – 0.162 | 0,009 | – 0.288 | 0,01 |

| Survey method*2 | ||||||||

| Written questionnaire | 0.113 | 0,05 | 0.087 | 0,038 | – 0.098 | 0,042 | – 0.021 | 0,045 |

| Internet-based | 0.013 | 0,058 | 0.084 | 0,052 | – 0.018 | 0,048 | 0.119 | 0,061 |

| Constants | 1.329 | 0.863 | 0.356 | – 0.508 | ||||

*1 Only users; *2 reference category: telephone interview; bold type: significant coefficients with level of significance at 5%

*3 Significant difference in coefficients between men and women with level of significance at 5%; b. regression coefficient; SE. standard error

eTable 6. Sample size, prevalence, estimated prevalence with 95% confidence intervals for alcohol use by survey year and sex.

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Survey year | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI |

| 1995 | 2919 | 85,9 | 87 | [86.0; 88.1] | 3615 | 73,6 | 76,7 | [75.5; 77.9] |

| 1997 | 3254 | 84,8 | 86,2 | [85.3; 87.1] | 3956 | 72,9 | 75,8 | [74.8; 76.9] |

| 2000 | 3264 | 89,9 | 85,3 | [84.6; 86.1] | 4043 | 82,6 | 75 | [74.1; 75.8] |

| 2003 | 3413 | 87 | 84,4 | [83.8; 85.0] | 4140 | 79,1 | 74,1 | [73.4; 74.8] |

| 2006 | 2984 | 79,8 | 83,4 | [82.9; 83.9] | 3754 | 69,7 | 73,2 | [72.6; 73.8] |

| 2009 | 3158 | 82,9 | 82,4 | [81.9; 82.9] | 3960 | 70,2 | 72,3 | [71.7; 72.8] |

| 2012 | 3321 | 80,4 | 81,3 | [80.6; 82.0] | 4422 | 69,3 | 71,3 | [70.6; 72.0] |

| 2015 | 3581 | 79,2 | 80,2 | [79.3; 81.2] | 4406 | 70,4 | 70,4 | [69.5; 71.3] |

| 2018 | 3657 | 78,8 | 79 | [77.8; 80.3] | 4473 | 69,8 | 69,4 | [68.2; 70.5] |

N. Sample size; Est. prev.. mean estimated prevalence;95% CI. 95% confidence interval

eTable 7. Sample size, prevalence, estimated prevalence with 95% confidence intervals for episodic heavy drinking use by survey year and sex.

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Survey year | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI |

| 1995 | 3539 | 47,5 | 46 | [44.4; 47.5] | 4240 | 19,8 | 16,1 | [15.2; 17.0] |

| 1997 | 3565 | 47,1 | 44,5 | [43.2; 45.7] | 4047 | 17,1 | 16 | [15.2; 16.7] |

| 2000 | 3638 | 40,7 | 43 | [42.0; 44.0] | 4372 | 13 | 15,8 | [15.2; 16.5] |

| 2003 | 3535 | 39,1 | 41,5 | [40.7; 42.3] | 4338 | 12,9 | 15,7 | [15.2; 16.2] |

| 2006 | 3054 | 37,1 | 40 | [39.3; 40.7] | 3841 | 14,4 | 15,6 | [15.1; 16.0] |

| 2009 | 3215 | 39,6 | 38,6 | [37.8; 39.3] | 4050 | 13,6 | 15,5 | [15.0; 15.9] |

| 2012 | 3402 | 37,9 | 37,1 | [36.3; 38.0] | 4522 | 15,4 | 15,3 | [14.8; 15.8] |

| 2015 | 3683 | 36,7 | 35,7 | [34.6; 36.8] | 4526 | 16,1 | 15,2 | [14.6; 15.8] |

| 2018 | 3713 | 35,3 | 34,4 | [33.1; 35.7] | 4535 | 17,3 | 15,1 | [14.3; 15.8] |

N. Sample size; Est. prev.. mean estimated prevalence;95% CI. 95% confidence interval

eTable 8. Results of the regression models for use of cannabis and other illegal drugs in the past 12 months.

| Cannabis | Other illegal drugs*1 | |||||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||

| Variables | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE |

| Curvilinear model | ||||||||

| Linear time | 0.094 | 0,012 | 0.135 | 0,014 | 0.035 | 0,02 | 0.120 | 0,023 |

| Quadratic time | – 0.002 | 0,004 | – 0.006 | 0,006 | 0.012 | 0,007 | 0.025 | 0,01 |

| Age | – 0.621 | 0,014 | – 0.670 | 0,017 | – 0.530 | 0,023 | – 0.603 | 0,03 |

| Survey method*2 | ||||||||

| Written questionnaire | 0.300 | 0,064 | 0.459 | 0,073 | 0.370 | 0,119 | 0.356 | 0,138 |

| Internet-based | 0.042 | 0,075 | 0.175 | 0,098 | 0.146 | 0,138 | – 0.166 | 0,198 |

| Constants | 0.851 | 0.265 | – 1.032 | – 1.629 | ||||

| Linear model | ||||||||

| lineare Zeit | 0.093*3 | 0,012 | 0.132*3 | 0,014 | 0.035 | 0,021 | 0.130 | 0,026 |

| Alter | –0.620 | 0,014 | – 0.670 | 0,017 | – 0.532 | 0,024 | – 0.604 | 0,03 |

| Survey method*2 | ||||||||

| Written questionnaire | 0.294 | 0,063 | 0.436 | 0,072 | 0.395 | 0,118 | 0.444 | 0,137 |

| Internet-based | 0.029 | 0,073 | 0.139 | 0,094 | 0.214 | 0,139 | – 0.032 | 0,192 |

| Constants | 0.838 | 0.238 | – 0.961 | – 1.512 | ||||

*1 Stimulants. ecstasy. LSD. heroin/other opiates. cocaine/crack; *2 reference category: telephone interview; bold type: significant coefficients with level of significance at 5%

*3 Significant difference in coefficients between men and women with level of significance at 5%; b. regression coefficient; SE. standard error

eTable 9. Sample size, prevalence, estimated prevalence with 95% confidence intervals for cannabis use by survey year and sex.

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Survey year | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI |

| 1995 | 3557 | 6.5 | 5.4 | [4.8; 5.9] | 4275 | 2,3 | 2,4 | [2.1; 2.8] |

| 1997 | 3727 | 5.4 | 5.9 | [5.4; 6.3] | 4293 | 2,7 | 2,7 | [2.4; 3.0] |

| 2000 | 3657 | 7.6 | 6.4 | [6.0; 6.8] | 4428 | 4,4 | 3,1 | [2.8; 3.4] |

| 2003 | 3585 | 9.1 | 6.9 | [6.6; 7.3] | 4416 | 4,7 | 3,5 | [3.2; 3.7] |

| 2006 | 3089 | 7.0 | 7.5 | [7.2; 7.9] | 3907 | 3,1 | 3,9 | [3.7; 4.1] |

| 2009 | 3234 | 7.0 | 8.2 | [7.8; 8.5] | 4089 | 3,4 | 4,4 | [4.2; 4.6] |

| 2012 | 3422 | 6.7 | 8.9 | [8.4; 9.3] | 4549 | 3,4 | 4,9 | [4.6; 5.2] |

| 2015 | 3701 | 8.7 | 9.6 | [9.0; 10.2] | 4551 | 5,3 | 5,5 | [5.1; 5.9] |

| 2018 | 3736 | 10,3 | 10,4 | [9.6; 11.1] | 4572 | 6,2 | 6,2 | [5.6; 6.7] |

N. Sample size; Est. prev.. mean estimated prevalence; 95% CI. 95% confidence interval

eTable 10. Sample size, prevalence, estimated prevalence with 95% confidence intervals for use of at least one illegal drug by survey year and sex.

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Survey year | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI |

| 1995 | 3550 | 2,9 | 2,1 | [1.7; 2.5] | 4276 | 0,8 | 0,6 | [0.4; 0.7] |

| 1997 | 3727 | 2,2 | 2,2 | [1.9; 2.5] | 4293 | 0,8 | 0,7 | [0.5; 0.8] |

| 2000 | 3657 | 2 | 2,2 | [2.0; 2.5] | 4428 | 1 | 0,8 | [0.6; 0.9] |

| 2003 | 3583 | 3 | 2,3 | [2.1; 2.5] | 4421 | 1 | 0,9 | [0.8; 1.0] |

| 2006 | 3041 | 2 | 2,4 | [2.2; 2.6] | 3858 | 0,7 | 1 | [0.9; 1.1] |

| 2009 | 3203 | 2 | 2,5 | [2.3; 2.7] | 4049 | 0,8 | 1,1 | [1.0; 1.3] |

| 2012 | 3414 | 1,9 | 2,6 | [2.3; 2.9] | 4534 | 0,8 | 1,3 | [1.1; 1.4] |

| 2015 | 3692 | 2,2 | 2,7 | [2.3; 3.0] | 4540 | 1,1 | 1,5 | [1.2; 1.7] |

| 2018 | 3734 | 3,1 | 2,8 | [2.3; 3.2] | 4572 | 2 | 1,6 | [1.3; 2.0] |

N. Sample size; Est. prev.. mean estimated prevalence; 95% CI. 95% confidence interval

eTable 11. Results of the regression models for intake of analgesics and hypnotics/sedatives in the past 30 days.

| Analgesics | Hypnotics/sedatives | |||||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||

| Variables | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE |

| Curvilinear model | ||||||||

| Linear time | 0.106 | 0,01 | 0.097 | 0,007 | –0.062 | 0,021 | – 0.082 | 0,014 |

| Quadratic time | 0.003 | 0,004 | 0.011 | 0,003 | 0.013 | 0,007 | 0.010 | 0,005 |

| Age | 0.209 | 0,014 | 0.129 | 0,011 | 0.346 | 0,033 | 0.438 | 0,028 |

| Survey method* | ||||||||

| Written questionnaire | 0.170 | 0,06 | 0.101 | 0,043 | 0.364 | 0,147 | 0.271 | 0,098 |

| Internet-based | – 0.165 | 0,074 | – 0.206 | 0,065 | 0.226 | 0,17 | – 0.049 | 0,145 |

| Constants | – 3.298 | – 2.443 | – 5.859 | – 5.904 | ||||

| Linear model | ||||||||

| Linear time | 0.107 | 0,01 | 0.097 | 0,008 | –0.072 | 0,021 | – 0.091 | 0,014 |

| Age | 0.209 | 0,014 | 0.128 | 0,011 | 0.345 | 0,033 | 0.438 | 0,028 |

| Survey method* | ||||||||

| Written questionnaire | 0.169 | 0,059 | 0.098 | 0,043 | 0.342 | 0,145 | 0.252 | 0,097 |

| Internet-based | – 0.153 | 0,072 | – 0.162 | 0,064 | 0.294 | 0,169 | 0.003 | 0,141 |

| Constants | – 3.277 | – 2.366 | – 5.759 | – 5.821 | ||||

* Reference category: telephone interview; bold type: significant coefficients with level of significance at 5%; b. regression coefficient; SE. standard error

eTable 12. Sample size, prevalence, estimated prevalence with 95% confidence intervals for intake of analgesics by survey year and sex.

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Survey year | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI |

| 1995 | 3482 | 9.6 | 7.9 | [7.2; 8.5] | 4153 | 14,3 | 11,9 | [11.1; 12.6] |

| 1997 | 3701 | 8.7 | 8.7 | [8.1; 9.3] | 4254 | 13,6 | 12,9 | [12.2; 13.6] |

| 2000 | 3623 | 9.0 | 9.5 | [9.0; 10.1] | 4365 | 12,5 | 14 | [13.5; 14.6] |

| 2003 | 3548 | 10,6 | 10,5 | [10.1; 10.9] | 4401 | 15,6 | 15,2 | [14.7; 15.7] |

| 2006 | 3037 | 10,2 | 11,5 | [11.1; 11.9] | 3863 | 14,1 | 16,5 | [16.1; 16.9] |

| 2009 | 3209 | 14,4 | 12,7 | [12.2; 13.1] | 4058 | 18 | 17,9 | [17.4; 18.3] |

| 2012 | 3387 | 14,4 | 13,9 | [13.2; 14.5] | 4516 | 19,6 | 19,3 | [18.7; 19.9] |

| 2015 | 3676 | 14,6 | 15,2 | [14.3; 16.1] | 4518 | 21,2 | 20,9 | [20.1; 21.6] |

| 2018 | 3709 | 14 | 16,6 | [15.4; 17.8] | 4518 | 21,2 | 22,5 | [21.5; 23.5] |

N. Sample size; Est. prev.. mean estimated prevalence; 95% CI. 95% confidence interval

eTable 13. Sample size, prevalence, estimated prevalence with 95% confidence intervals for intake of hypnotics/sedatives by survey year and sex.

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Survey year | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI | N | Prevalence | Est. prev. | 95% CI |

| 1995 | 3459 | 4,6 | 3,7 | [3.1; 4.3] | 4127 | 6,4 | 5,6 | [5.0; 6.2] |

| 1997 | 3701 | 3,2 | 3,4 | [3.0; 3.9] | 4254 | 6,4 | 5,2 | [4.7; 5.7] |

| 2000 | 3579 | 3,2 | 3,2 | [2.9; 3.5] | 4287 | 4,1 | 4,8 | [4.5; 5.2] |

| 2003 | 3550 | 2,7 | 3 | [2.8; 3.2] | 4401 | 4,2 | 4,4 | [4.2; 4.7] |

| 2006 | 3039 | 2,4 | 2,8 | [2.6; 3.0] | 3864 | 3,5 | 4,1 | [3.9; 4.3] |

| 2009 | 3209 | 2,6 | 2,6 | [2.4; 2.8] | 4057 | 3,5 | 3,8 | [3.6; 4.1] |

| 2012 | 3404 | 2,9 | 2,4 | [2.1; 2.7] | 4524 | 4,3 | 3,5 | [3.2; 3.8] |

| 2015 | 3685 | 1,9 | 2,3 | [1.9; 2.6] | 4539 | 3,5 | 3,3 | [2.9; 3.6] |

| 2018 | 3720 | 2,1 | 2,1 | [1.7; 2.5] | 4543 | 2,2 | 3 | [2.6; 3.4] |

N. Sample size; Est. prev.. mean estimated prevalence; 95% CI. 95% confidence interval

eTable 14. Trends in substance-related disorders according to DSM-IV for 18- to 59-year-olds (12-month prevalence).

| 1997 | 2000 | 2006 | 2009 | 2012 | 2018 | ||

| % [95% CI] | % [95% CI] | % [95% CI] | % [95% CI] | % [95% CI] | % [95% CI] | ||

| Nicotine | Dependence | 7.4 [6.7; 8.1] | 9.8* [9.0; 10.7] | 7.9 [7.3; 8.6] | 9.1* [8.4; 9.9] | 6.8 [6.2; 7.5] | |

| Alcohol | Abuse | 3.4 [2.9; 4.1] | 3.8* [3.3; 4.3] | 3.6* [3.2; 4.0] | 2.8 [2.4; 3.2] | ||

| Dependence | 2.6 [2.1; 3.1] | 2.9 [2.5; 3.3] | 2.8 [2.4; 3.2] | 3.7* [3.2; 4.2] | 3.4 [3.0; 3.8] | ||

| Cannabis | Abuse | 0.5 [0.3; 0.8] | 0.7 [0.6; 1.0] | 0.5 [0.4; 0.7] | 0.6 [0.4; 0.7] | 0.6 [0.5; 0.7] | |

| Dependence | 0.4 [0.2; 0.7] | 0.3* [0.2; 0.5] | 0.5 [0.4; 0.7] | 0.5 [0.4; 0.7] | 0.6 [0.4; 0.8] | ||

| Analgesics | Dependence | 2.2 [1.9; 2.6] | 3.0* [2.6; 3.4] | 2.5 [2.1; 2.9] | |||

| Hypnotics/sedatives | Dependence | 0.8 [0.6; 1.0] | 1.4* [1.2; 1.7] | 0.6 [0.4; 0.8] | |||

The prevalence figures for the trends in substance-related disorders difference slightly from the publications in earlier years. because the coding of individual diagnostic criteria was adjusted.

* p <0.05 for comparison with reference year 2018; logistic regression for prediction of prevalence with year. age. survey method

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Pfeiffer-Gerschel has received lecture fees from Sanofi.

The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Funding

The Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse was supported by funding from the German Federal Ministry of Health (project no. ZMVI1–2517DSM200). The funder imposed no conditions.

References

- 1.Pergolizzi JVJ, LeQuang JAT R.Jr., Raffa RB, Group NR Going beyond prescription pain relievers to understand the opioid epidemic: the role of illicit fentanyl, new psychoactive substances, and street heroin. Postgrad Med. 2018;130:1–8. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2018.1407618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration. National drug threat assessment summary. wwwdeagov/documents/2016/11/01/2016-national-drug-threat-assessment (last accessed on 19 June 2019) 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang KC, Wang JD, Saxon A, Matthews AG, Woody G, Hser YI. Causes of death and expected years of life lost among treated opioid-dependent individuals in the United States and Taiwan. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;43:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraus L, Piontek D, Atzendorf J, Gomes de Matos E. Zeitliche Entwicklungen im Substanzkonsum in der deutschen Allgemeinbevölkerung: Ein Rückblick auf zwei Dekaden. Sucht. 2016;62:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lachner G, Wittchen H-U, Perkonigg A, et al. Structure, content and reliability of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) substance use sections. Eur Addict Res. 1998;4:28–41. doi: 10.1159/000018922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wittchen H-U, Beloch E, Garczynski E, et al. Max-Planck-Institut für Psychiatrie, Klinisches Institut. München: 1995. Münchener Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI), Paper-pencil 22, 2/95. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atzendorf J, Rauschert C, Seitz NN, Lochbühler K, Kraus L. The use of alcohol, tobacco, illegal drugs and medicines—an estimate of consumption and substance-related disorders in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:577–584. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heeringa SG, West BT, Berglund PA. Applied survey data analysis 2nd edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeiher J, Finger JD, Kuntz B, Hoebel J, Lampert T, Starker A. Zeitliche Trends beim Rauchverhalten Erwachsener in Deutschland. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2018;61:1365–1376. doi: 10.1007/s00103-018-2817-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orth B, Merkel C. Rauchen bei Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen in Deutschland Ergebnisse des Alkoholsurveys 2016 und Trends. BZgA-Forschungsbericht. Köln: Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung. 2018 doi: 10.17623/BZGA:225-ALKSY16-RAU-DE-1.0. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotz D, Böckmann M, Kastaun S. The use of tobacco, e-cigarettes, and methods to quit smoking in Germany—a representative study using 6 waves of data over 12 months (the DEBRA study) Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:235–244. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hublet A, Bendtsen P, de Looze ME, et al. Trends in the co-occurrence of tobacco and cannabis use in 15-year-olds from 2002 to 2010 in 28 countries of Europe and North America. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25:73–75. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraus L, Seitz N-N, Piontek D, et al. ´Are the times a-changin‘? Trends in adolescent substance use in Europe. Addiction. 2018;113:1317–1332. doi: 10.1111/add.14201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lampert T. Deutsche Hauptstelle für Suchtfragen e.V. (DHS), editor. Tabak - Zahlen und Fakten zum Konsum Jahrbuch Sucht 2013. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers. 2013:67–90. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas RE, Baker PR, Thomas BC, Lorenzetti DL. Familybased programmes for preventing smoking by children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;27 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004493.pub3. CD004493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas RE, McLellan J, Perera R. Schoolbased programmes for preventing smoking. Evid Based Child Health. 2013;8:1616–2040. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaller K, Mons U. Tabakprävention in Deutschland und international. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2018;61:1429–1438. doi: 10.1007/s00103-018-2819-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraus L, Piontek D, Atzendorf J, Gomes de Matos E. Zeitliche Entwicklungen im Substanzkonsum in der deutschen Allgemeinbevölkerung. Ein Rückblick auf zwei Dekaden. Sucht. 2016;62:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peacock A, Leung J, Larney S, et al. Global statistics on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use: 2017 status report. Addiction. 2018;113:1905–1926. doi: 10.1111/add.14234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babor TF, Caetano R, Casswell S, et al. Oxford University Press. Oxford: 2010. Alcohol: no ordinary commodity 2nd edition. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraus L, Müller S, Pabst A. Alkoholpolitik. Suchttherapie. 2008;9:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orth B. Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung. Köln: 2017. Der Alkoholkonsum Jugendlicher und junger Erwachsener in Deutschland Ergebnisse des Alkoholsurveys 2016 und Trends. BZgA-Forschungsbericht. [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Looze M, Raaijmakers Q, Ter Bogt T, et al. Decreases in adolescent weekly alcohol use in Europe and North America: evidence from 28 countries from 2002 to 2010. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25:69–72. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livingston M, Raninen J, Slade T, Sift W, Lloyd B, Dietze P. Understanding trends in Australian alcohol consumption—an age-period-cohort model. Addiction. 2016;111:1590–1598. doi: 10.1111/add.13396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraus L, Room R, Livingston M, Pennay A, Holmes J, Törrönen J. Long waves of consumption or a unique social generation? Exploring recent declines in youth drinking. Addict Res Theory. 2019 doi: 10.1080/16066359.2019.1629426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraus L, Piontek D, Pfeiffer-Gerschel T, Rehm J. Inanspruchnahme gesundheitlicher Versorgung durch Alkoholabhängige. Suchttherapie. 2015;16:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaner EF, Beyer FR, Muirhead C, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub4. CD004148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orth B, Merkel C. Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung. Köln: 2018. Der Cannabiskonsum Jugendlicher und junger Erwachsener in Deutschland Ergebnisse des Alkoholsurveys 2016 und Trends BZgA-Forschungsbericht. [Google Scholar]

- 29.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) European drug report 2018. Trends and developments. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union 2018. www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/edr/trends-developments/2018_en (last accessed on 19 June 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasin DS. US epidemiology of cannabis use and associated problems. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43 doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cerda M, Kilmer B. Uruguay’s middle-ground approach to cannabis legalization. Inter J Drug Policy. 2017;42:118–120. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carliner H, Brown QL, Sarvet AL, Hasin DS. Cannabis use, attitudes, and legal status in the US. A review. Prev Med. 2017;104:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Government of Canada. Cannabis laws and regulations. About cannabis, process of legalization, cannabis in provinces and territories, driving laws. www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/laws-regulations.html (last accessed on 19 June 2019) 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon R. Prohibition, Legalisierung, Dekriminalisierung: Diskussion einer Neugestaltung des Cannabisrechts. Sucht. 2016;62:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Compton WM, Han B, Jones CM, Blanco C, Hughes A. Marijuana use and use disorders in adults in the USA, 2002-14: analysis of annual cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:954–964. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fazel S, Khosla V, Doll H, Geddes J. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 2008;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225. e225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kraus L, Seitz N-N, Schulte B, et al. Estimation of the number of people with opioid addiction in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:137–143. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwabe U, Paffrath D, Ludwig W-D, Klauber J. Springer. Berlin: 2018. Arzneiverordnungs-Report 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kraus L, Pfeiffer-Gerschel T, Seitz N-N, Kurz A. Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Berlin: 2018. Analyse drogeninduzierter Todesfälle. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verthein W, Holzbach R, Neumann-Runde E, Martens M-S. Benzodiazepine und Z-Substanzen - Analyse der kassenärztlichen Verschreibung von 2006 bis 2015. Psychiat Prax, 2019 doi: 10.1055/a-0961-2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Gakidou E, Afshin A, Abajobir AA, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1345–1422. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32366-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Degenhardt L, Hall W. Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet. 2012;379:55–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Hackshaw A, Morris JK, Boniface S, Tang JT, Milenkovic D. Low cigarette consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: meta-analysis of 141 cohort studies in 55 study reports. BMJ. 2018 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Neubauer S, Welte R, Beiche A, Koenig HH, Buesch K, Leidl R. Mortality, morbidity and costs attributable to smoking in Germany: update and a 10-year comparison. Tob Control. 2006;15:464–471. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.016030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.World Health Organization. WHO Press. Geneva: 2005. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. [Google Scholar]

- E6.Donnel A, Anderson P, Newbury-Birch D, et al. The impact of brief alcohol interventions in primary healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49:66–78. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Buth S, Holzbach R, Martens MS, Neumann-Runde E, Meiners O, Verthein U. Problematic medication with benzodiazepines, “Z-drugs”, and opioid analgesics—an analysis of national health insurance prescription data from 2006-2016. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116 doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Piontek D, Kraus L. Epidemiologischer Suchtsurvey 2015. Sucht. 2016;62:257–320. [Google Scholar]

- E9.Kraus L, Piontek D, Pabst A, Gomes de Matos E. Studiendesign und Methodik des Epidemiologischen Suchtsurveys 2012. Sucht. 2013;59:309–320. [Google Scholar]

- E10.Kraus L, Pabst A. Studiendesign und Methodik des Epidemiologischen Suchtsurveys 2009. Sucht. 2010;56:315–326. [Google Scholar]

- E11.Kraus L, Baumeister SE. Studiendesign und Methodik des Epidemiologischen Suchtsurveys 2006. Sucht. 2008;54(1):S6–S15. [Google Scholar]

- E12.Kraus L, Augustin R. Repräsentativerhebung zum Gebrauch und Missbrauch psychoaktiver Substanzen bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland Epidemiologischer Suchtsurvey 2003. Sucht. 2005;51:S4–S57. [Google Scholar]

- E13.Kraus L, Augustin R. Repräsentativerhebung zum Gebrauch psychoaktiver Substanzen bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland 2000. Sucht. 2001;47(1):S3–S86. [Google Scholar]

- E14.Kraus L, Bauernfeind R. Repräsentativerhebung zum Konsum psychoaktiver Substanzen bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland 1997. Sucht. 1998;44(1):S3–S82. [Google Scholar]

- E15.Herbst K, Kraus L, Scherer K. Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Bonn: 1996. Repräsentativerhebung zum Gebrauch psychoaktiver Substanzen bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland Schriftliche Erhebung. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Details of methods

Study design and samples

The data used for this study came from nine surveys conducted in the course of the Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (ESA) between 1995 and 2018 (every 3rd year from 1997 onwards). The case numbers varied from 7833 (1995) to 9267 (2018); the response rates ranged between 42% (2018) and 65% (1995 and 1997). The change in the upper age limit during the observation period limits the analysis of trends to the age range 18 to 59 years (etable 1).

Weighting

The goal of the ESA is to provide data on substance use representative for the German population between 18 and 59 years (survey years 1995 to 2003) or between 18 and 64 years (survey years 2006 to 2018). In each individual survey, weights were calculated to adjust the distribution of basic sample characteristics to the general population. Since 2006, weights have been determined to compensate for the disproportional composition of the age groups in the sample. These weights are inversely proportional to the likelihood of selection at the respective probability level. Furthermore, the weights accounted for the marginal distributions of the external characteristics federal state, community size, and sex in the 18- to 64-year old population of the microcensus for the survey year concerned. Detailed information on the weighting for the different survey years can be found in the individual source publications (etable 1).

Instruments

Tobacco use

Tobacco use was defined as smoking at least one cigarette, cigar, cigarillo, or pipe in the 30-day period prior to the survey. Daily use was defined as smoking at least one cigarette per day over the preceding 30 days.

Alcohol use

The prevalence of alcohol use relates to the 30-day period preceding the survey. Alcoholic drinks included beer, wine/sparkling wine, and spirits, plus alcopops (in 2006) or mixed drinks containing alcohol (from 2009; e.g., alcopops, long drinks, cocktails, punch). Episodic heavy drinking was defined as consumption of five or more glasses of alcohol (ca. 70 g pure alcohol) in a single day at least once in the preceding 30 days.

Use of illegal drugs

The prevalence of use of cannabis and at least one other illegal drug relates to the 12-month period preceding the survey. Because of the low case numbers, amphetamine/methamphetamine, ecstasy, LSD, heroin/other opiates, cocaine/crack, and hallucinogenic mushrooms were combined into the category “other illegal drugs.”

Medication intake

The survey asked about intake of analgesics and hypnotics/sedatives in the previous 30 days. Weekly use comprised intake at least once per week. The survey participants allocated each medication they had taken to one of the categories in a list of the most common types of preparations.

Substance-related disorders

The documentation of substance-related disorders caused by alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, amphetamine, analgesics, hypnotics, and sedatives was based on the Munich Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI). Disorders occurring in the previous 12 months were classified according to the criteria of DSM-IV and divided into abuse and dependence. Substance-related disorders according to DSM-IV were documented in the individual surveys as follows: nicotine: 2000, 2006, 2009, 2012, 2018; alcohol and cannabis: 1997, 2006, 2012, 2018; analgesics, hypnotics/sedatives: 2000, 2012, 2018.

Statistical analyses

Missing data were partly replaced by means of a logical imputation process. For example, if a filtering question regarding general drug use was answered in the negative the missing data on use of the various substances was replaced with non-use, or a missing value for lifetime use in the presence of a positive response for 12-month use was replaced with a positive response for lifetime prevalence. Moreover, missing data per year were excluded from the regression analyses for trends per substance, which in analogy to the cross section corresponds to pairwise exclusion of persons with missing data.

Sex-specific analyses of the trends in substance use and substance-related disorders are based on binomial logistic regression models. For the dependent variable “substance use,” the survey year was employed in the model as continuous predictor “time” with equidistant intervals. For the dependent variable “substance-related disorders,” the survey year was used as categorical predictor, because disorders were not documented at regular intervals.

Age and survey type were used as control variables in all regression models so that effects of age or survey type could be excluded. On grounds of the complex sample design, the weights for each survey year were included in the statistical analyses. To take account of the multistage selection procedure, standard errors based on Taylor series were calculated using survey-specific statistical methods (8). The level of significance was set at 5%.

Models for substance use

In the models for the trends in substance use, “time” was mean-centered and included as a linear and/or quadratic predictor. Statistically significant regression coefficients indicate linear or curvilinear trends. Negative values of the regression coefficients for linear time bL characterize a falling, positive values a rising tendency. The regression coefficient for quadratic time bQ indicates both the direction and the steepness of the curve in a curvilinear trend. A positive value means that the curve is directed upwards or convex, while a negative value shows that the curve is directed downwards or concave. In a significant curvilinear trend both regression coefficients (linear and quadratic) are considered when interpreting the results.

When the trends were similar in men and women, they were compared between the sexes. In this event, the regression coefficients were compared for the linear or quadratic predictor “time” using a Wald test. Predicted values for each person were calculated on the basis of the models. The mean predicted values, their 95% confidence intervals, and the prevalence by survey year and sex are shown in the Figures in the body of the article. The detailed results of the regression models and data on sample size, prevalence rates, and their estimated mean values and 95% confidence intervals are shown in eTables 2– 13, based on the regression models for each survey year by sex.

Models for substance-related disorders

Analyses of the trends in substance-related disorders were performed for the whole sample, with 2018 as reference year for the categorical variable “survey year” (see analyses of all 18- to 59-year-olds in eTable 14).

Tobacco

The prevalence of tobacco use shows a curvilinear decreasing trend for both sexes (men: bL = -0.088, bQ = -0.005; women: bL = -0.051, bQ = -0.014), with a more pronounced curvature for women than for men (F [1; 3 878] = 7.7; p < 0.01). A comparable trend is seen for the prevalence of daily tobacco use (men: bL = -0.116, bQ = -0.009; women: bL = -0.076, bQ = -0.019; F [1; 3 878] = 6.9; p < 0.01) (eTables 2– 4).

Alcohol

The prevalence of alcohol use shows a linear decreasing trend (bL = -0.072) for men, while a concave decreasing trend is seen for women (bQ = -0.007). The decrease is greater for women than for men. The fluctuations in prevalence were smoothed by the model and the resulting predicted values. The prevalence of episodic heavy drinking displays a convex trend for both men (bQ = 0.007) and women (bQ = 0.024), representing a slightly accelerated increase with a more pronounced curvature for women (F [1; 3 875] = 23.79; p <0.001). Taking into account the values of the linear time coefficients (men: bL = -0.065; women: bL = -0.005), an increasing trend can be assumed only for women (eTables 5– 7).

Illegal drugs

The prevalence of cannabis use shows a linear trend in both sexes. The increase in the proportion of women using cannabis is statistically significantly stronger than in men (men: bL = 0.093, women: bL = 0.132; F[1; 3 877] = 4.88, p <0.05). The prevalence of the use of other illegal drugs is constant in men and increasing linearly in women (bL = 0.120) (eTables 8– 10).

Medications

For men, the prevalence of weekly intake of analgesics is increasing linearly (linear time: bL = 0.107) and that of hypnotics/sedatives is decreasing linearly (linear time: bL = -0.062). Although a generally accelerated convex increase is seen for both indicators in women (analgesics: bQ = 0.011, hypnotics/sedatives: bQ = 0.010), the growth in the prevalence of intake of hypnotics/sedatives is less pronounced, because of the negative coefficients of linear time (bL = -0.082), than is the case for analgesics, where the positive coefficient of linear time (bL = 0.097) accelerates the growth (eTables 11– 13).

Substance-related disorders

Among the substance-related disorders, nicotine dependence shows the highest prevalence and the strongest fluctuations over time (eTable 14, eFigure 1). Compared with 2018 (6.8%), the prevalence was significantly higher in both 2006 (9.8%; t = 3.05; p <0.01) and 2012 (9.1%; t = 3.34; p <0.001).

The prevalence of alcohol abuse was significantly lower in 2018 (2.7%) than in 2006 (3.8%; t = 3.36; p <0.001) and 2012 (3.6%; t = 3.32; p <0.001). After a significant peak in 2012 (3.7%; t=5.24; p <0.001), the prevalence of alcohol dependence in 2018 was comparable with that in earlier years. With the exception of 2012 (0.3%; t = -2.06; p <0.05), the prevalence of cannabis-related disorders shows a generally constant trend.

The prevalence of mental disorders caused by analgesics and hypnotics/sedatives in 2018 fell back to the level in 2000.