Abstract

The growth in the number of cancer survivors in the face of projected health-care workforce shortages will challenge the US health-care system in delivering follow-up care. New methods of delivering follow-up care are needed that address the ongoing needs of survivors without overwhelming already overflowing oncology clinics or shuttling all follow-up patients to primary care providers. One potential solution, proposed for over a decade, lies in adopting a personalized approach to care in which survivors are triaged or risk-stratified to distinct care pathways based on the complexity of their needs and the types of providers their care requires. Although other approaches may emerge, we advocate for development, testing, and implementation of a risk-stratified approach as a means to address this problem. This commentary reviews what is needed to shift to a risk-stratified approach in delivering survivorship care in the United States.

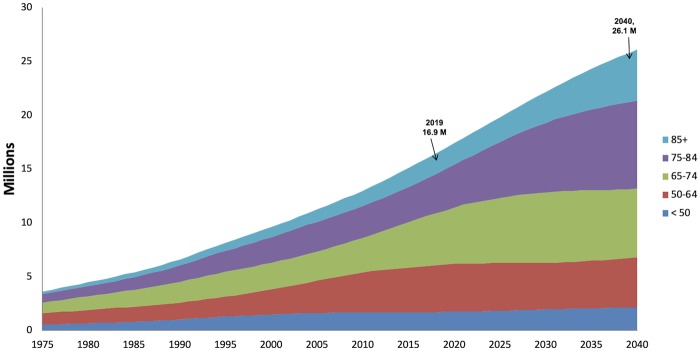

Growth in the prevalence of cancer survivors over the last decade reflects improvements in the early detection and treatment of cancer as well as the aging population (Figure 1). The number of cancer survivors in the United States is projected to rise from 15.5 million currently (1) to 26 million by 2040 (2). Longevity after cancer treatment has increased as well, and currently two-thirds of survivors have lived for five or more years since diagnosis (2). Although the definition of a cancer survivor includes patients from the time of diagnosis forward (3), this article focuses on posttreatment cancer survivors and their need for ongoing follow-up care to screen for and treat recurrences and additional cancers; manage chronic and late effects of cancer and treatment; address psychological, social, economic, and family concerns; encourage healthy lifestyle behaviors; and increase adherence to long-term treatment and follow-up care regimens (4–7). Currently, this care occurs during follow-up visits with the medical oncologist and/or the primary care provider (PCP). However, a confluence of shifting factors is creating a perfect storm that means “business as usual” for US health-care systems will increasingly be unable to deliver posttreatment follow-up care for cancer survivors that meet their needs.

Figure 1.

Growth in the number of cancer survivors over time in the United States.

Business as Usual Cannot Continue Because There Are an Increasing Number of Survivors Who Need Complex Care

Despite the decade of progress (8) since the Institute of Medicine’s Lost in Transition Report that brought attention to the unmet needs of posttreatment cancer survivors (9), a new workshop from the National Academy of Medicine finds current models of follow-up care fail to meet the needs of many survivors (10). The inability of current care models to meet survivors’ needs will only worsen because the aging of the US population means that an increasing number of survivors are over age 65 years (currently 62% but growing to 73% by 2040) and are more likely to need management of multiple comorbid conditions in addition to their cancer-specific concerns (11). Most of these people are in poorer health compared with the general population without cancer and have multiple (average of five) co-morbid conditions that need to be managed by the PCP with referrals to multiple specialists when needed (11–18).

Business as Usual Cannot Continue Because Attempting to See All Follow-Up Patients in Oncology Clinics Will Become Impossible

Many survivors prefer to be followed by their oncologist (19) due to emotional connections developed during their cancer experience and concerns about their PCP’s lack of cancer expertise and lack of involvement in their cancer care. Although some survivors are currently followed by their oncology team, attempting to follow all cancer survivors for long periods of time after diagnosis in oncology settings will become increasingly impossible. While the number of people newly diagnosed with cancer has gradually increased (about 2% per year from 1.4 million in 2008 to 1.7 million in 2018), the number of posttreatment survivors has grown cumulatively and at a faster rate (>3.5% per year from 10.8 million to 15.5 million in the same 10-year span) (20). The growth in the number of survivors is creating a large volume of long-term follow-up patients relative to the number of newly diagnosed patients or those being actively managed for metastatic disease and end-of-life care. The National Cancer Institute estimates that in the decade between 2012 and 2022, the number of survivors who are 5 of more years from diagnosis is expected to increase by 37% (8.7 million to 11.9 million) while the number of survivors less than 5 years from diagnosis will increase only 22% (4.9 million to 6 million) (21). The rising number of patients needing oncology care coupled with the shortage of oncologists is already increasing waitlist times in oncology clinics across the United States (22).

The workforce shortage will only get worse. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) estimated that a nearly 56% growth in demand for oncology services, coupled with only a 14% growth in supply of such services, would lead to demand far exceeding supply by the year 2020 (23,24). Because this imbalance is projected to lead to a shortage of almost 1500 oncologists needed for the initial care of cancer patients by 2025 (25), medical oncologists cannot possibly provide ongoing follow-up care for all survivors.

An ASCO workforce report demonstrated that even if multiple strategies are enacted to handle the increasing patient load (more oncology fellowship slots, delaying oncologist retirements, improved oncology clinic efficiency, etc.), there will simply not be enough oncologists to see all the newly diagnosed patients needing initial cancer therapy (26). Attempting to see all follow-up patients in oncology practices would exacerbate forecasted delays in new patient appointments or in the timing of follow-up visits for survivors. The volume will exceed clinician bandwidth, available office space, and other resources for adequately coordinating clinical care. The increasing patient rosters and the associated paperwork/charting demands are also decreasing oncologists’ time for research, educational pursuits, and engagement in other meaningful activities. These pressures and lack of intellectual enrichment are contributing to burnout among oncologists (27). A recent meta-analysis found that 32% of oncologists had high burnout, affecting oncologists’ quality of life and also contributing to poorer clinical care (28).

Business as Usual Cannot Continue Because Attempting to See All Follow-Up Patients in Primary Care Is Unlikely to Meet Survivors’ Needs

The oncologist shortage means that an increasing number of cancer survivors will need posttreatment follow-up care from other clinicians, including PCPs. However, expecting PCPs alone to meet the needs of survivors who need complex care is unlikely to be successful given the vast majority of PCPs receive little education or training in how to provide cancer follow-up care (29) and are also experiencing their own workforce shortages (30). Additionally, PCPs are expected to coordinate care of survivors with clinicians from other specialties as needed to meet survivors’ needs. However, the United States is also facing health-care provider shortages in advanced practice providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants), pharmacists, and mental health clinicians, which further complicate provision of adequate follow-up cancer care (31).

Business as Usual Cannot Continue Because of Shifts to Value-Based Care and the Need to Control Costs

Costs of cancer care in the United States are increasing and projected to reach over $157 billion annually by 2020 (32). These costs are coupled with excess costs of being a survivor (33), estimated at $25–48 billion annually. These costs are borne by health-care delivery systems but also by patients and families, an increasing percentage of whom are experiencing financial hardship from cancer care costs (34). These rising costs will limit resources of health-care systems to offer patients and their families to participate in needed follow-up care and services and contribute to disparities in health outcomes already seen in many subgroups of survivors (35). These trends are occurring just as US health-care systems are beginning to shift from volume-based care to value-based care, bringing increased attention to outcomes and cost control (36–38). The alignment of these factors with the shift to value-based reimbursement necessitates the development of methods of care delivery that optimize patient outcomes and promote health equity while dealing with provider shortages and controlling costs to health-care delivery systems and to patients and families.

Innovative Care Delivery Models Are Needed

With the increasing impossibility of seeing all follow-up patients in oncology or primary care clinics and continuing reports of care that fails to meet survivors’ needs, why have alternative models not yet been developed and implemented widely? This failure to plan is due in part to a failure to conceptualize what the increasing number of cancer survivors means for practice, research, or education, and a “head in the sand” approach, which is no longer tenable. In most practice settings, the number of annual new cases is used as a proxy for cancer program size, planning program resources, and facilities growth and in determining workforce needs. Cancer trends over the last 30 years show that although the number of new cases has been growing linearly and slowly, it is a poor measure for anticipating overall needs including clinical resources, health-care workforce, and facility space and staffing needs. It also fails to identify pressing research questions about caring for this population and in identifying and meeting the education needs of clinicians, survivors, and their caregivers. Additionally, because the stress of specializing in oncology and regularly providing bad news to patients contributes to burnout (27,39), it must be kept in mind that oncologists benefit from seeing patients who are doing well. Seeing a wide range of cancer patients can contribute to their own mental health, provide a sense of accomplishment, and prevent burnout. Therefore, we need to rethink how we deliver follow-up visits for cancer survivors in a way that meets survivors’ needs while contributing to job satisfaction of our clinicians.

Personalized, Risk-Stratified, Follow-Up Care Presents a Potential Solution

It is clear that new methods of delivering follow-up care for oncology patients are needed that address patients’ ongoing needs without overwhelming already overflowing oncology clinics or shuttling all follow-up patients to PCPs who have neither the time nor the expertise to meet survivors’ needs. With the shift to value-based care, new follow-up care methods must also help achieve these improved outcomes while controlling costs over the long term and providing care in ways that address rather than exacerbate socio-economic health disparities (40).

One potential solution, proposed for over a decade, lies in adopting a personalized approach to care in which patients are triaged to distinct care pathways based on the complexity of their needs and the types of providers their care requires. To work, the stratification should be based on multiple factors beyond overall prognosis and risk of recurrence, including the severity of chronic effects of treatment; their risk of late effects and additional cancers; their functional ability; their personal resources and capacity to self-manage aspects of their care; and the knowledge level of their providers and capacity of their health-care system to detect and manage issues that arise. This type of personalized approach to follow-up care is referred to as “risk-stratified care” and is in use in the United Kingdom, Australia, and other countries (41,42). In practice, patients with minimal ongoing problems who are considered at low risk of late effects may be followed early after treatment ends in primary care, whereas patients who have multiple complex needs may be followed in oncology and by a multi-disciplinary team of specialty providers, as needed. Patients with moderate levels of risk and ongoing problems may be followed by advanced practice providers focusing on survivors or “shared care” with both primary care and oncology expertise.

Versions of a personalized approach to cancer care, like the risk-stratified model in the United Kingdom, have been suggested in the United States since 2006 but have yet to be adopted (43–46). This approach has been tested in Northern Ireland for breast cancer patients. Results showed that implementing this care improved receipt of timely follow-up mammograms by 20% while decreasing waiting list time in surgery and medical oncology by 34% and freeing up more of clinicians’ time for patients with complex needs (47). Similar testing in Canada has shown that low-risk breast cancer survivors who are transitioned from oncology-led to primary care-based follow-up have lower rates of hospitalizations, fewer oncology visits but equivalent primary care visits, greater rates of mammography but fewer other diagnostic tests, lower overall health-care costs, and equivalent survival compared to patients who were not transitioned using a risk-stratified model (48). Other models that have been described include disease-specific survivorship clinics, consultation survivorship clinics, and multidisciplinary survivorship clinics (46) but do not address the patient volume and workforce issues described here.

Implementation of a personalized or risk-stratified approach to follow-up care like the United Kingdom or Canadian risk-stratified care is likely to be more complex in the United States. The United Kingdom and Canada have single-payer health systems, whereas the United States has diversity in care delivery systems and current problems with fragmentation of care components. Still, several lessons learned from countries where risk-stratified care has been tested are helpful in considering how to implement a similar model in the United States. Pilot testing in the United Kingdom demonstrated that rather than being based on a complex algorithm, risk-stratification required identifying patients who need close clinical follow-up and then helping the majority of patients to self-manage issues they experience with limited clinician involvement except for surveillance or screening tests. Self-management is defined as a person’s ability to manage the symptoms and consequences of living with a chronic condition, including treatment, physical, social, and lifestyle changes (49). In the case of follow-up care, this means educating patients on what to look out for in terms of recurrences, additional cancers, and late effects, having systems set up to detect and manage problems that occur, and providing patients with a pathway back to their oncology team when needed (50). The UK pilot studies demonstrated that 50% of colorectal, 80% of breast, and 50% of prostate cancer patients treated with curative intent were able to self-manage posttreatment (51). Of note, these are the diseases with the highest volume of survivors needing follow-up care in the United States. Further, supporting the majority of patients in self-management met patients’ needs, freed up oncologists’ time, and enhanced the quality and productivity of the healthcare system, which is projected to save England 90 million pounds over 5 years (52). We need scalable pilot studies in the United States to evaluate similar outcomes in our health-care system.

Research, Practice, Education, and Health Policy Changes Needed

The United States needs multi-level interventions to align workforce, health-care system, facilities, and programs to specifically address survivors’ care. We believe a risk-stratified approach offers the potential for personalized follow-up care that will provide the essential components of survivorship care (follow-up care to screen and treat recurrences and additional cancers; manage chronic and late effects of cancer and its treatment; address psychological, social, economic, and family concerns; improve lifestyle behaviors; and increase adherence to long-term treatment and follow-up care guidelines) while being efficient and cost effective. It will be crucial to address issues of dissemination and implementation early in this process in a shift from our current system of follow-up care to a more personalized, stratified approach in diverse settings.

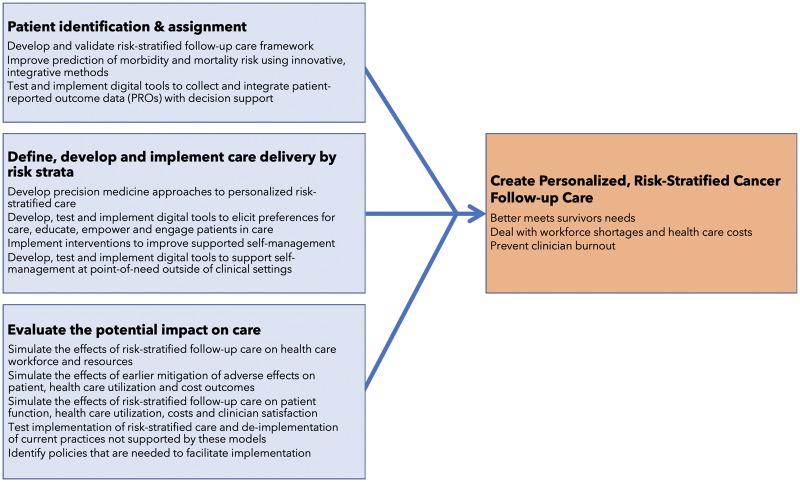

We have begun efforts to address this needed shift in follow-up care. The American Cancer Society and ASCO convened a Summit in January 2018 to identify strategies for implementation. This group outlined a set of recommendations including research, practice change, clinical guidelines development, and policy reform to support practice changes (53). Additionally, the American Cancer Society (ACS) and the Oncology Nursing Society conducted a roundtable on mitigating the adverse effects of cancer and its therapy in March of 2018. This group discussed the roles of digital tools in identifying needs and delivering personalized risk-stratified interventions, facilitating timely referrals or prescriptions, and especially in supporting self-management by survivors. Together, these efforts have pointed to a set of strategies that must be enacted to test and implement effective risk-stratified approaches for follow-up care (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Coordinated strategies needed to develop personalized, risk-stratified cancer follow-up care.

Research needs to be conducted to inform both how to risk stratify survivors and deliver risk-stratified interventions to encourage a systematic change in delivering follow-up care for survivors after treatment. Part of this effort must identify how to support survivors in self-managing their health to the extent possible, using eHealth and community- or home-based interventions where needed rather than the clinical care system. Educational efforts will need to target all clinicians, to increase their comfort in delivering care, and survivors and caregivers who will be assuming more self-management. A particularly important aspect of the needed culture change in survivorship care will need to be initiated from the time of diagnosis to establish expectations on behalf of the oncology team, patients and families, and PCPs. Experts in dissemination and implementation science will need to weigh in on the best ways to introduce these changes while acknowledging the emotional connections between survivors and their oncology team. We also need to maintain exposure for the oncology team to survivors who are doing well, even if in other settings or mechanisms.

Additionally, we need a more comprehensive appraisal of what our health-care system needs to deliver care to those with cancer. Rand Corporation recently published a report regarding the readiness for the US health-care system to diagnose and treat people with Alzheimer’s (54). They asked two important questions that are relevant to the cancer survivor population: How prepared is the US health-care system to handle the potential caseload when a disease-modifying therapy for Alzheimer’s disease becomes available? What can be done to reduce capacity limitations and avoid delays in access to care? A similar effort in survivorship could help health-care systems understand the resources and workforce needed to address the growing population of cancer survivors. Additional simulation modeling studies are needed to anticipate the effects of risk-stratified care and related shifts (more patients in a self-management pathway, the introduction of eHealth digital tools to facilitate care) on patient outcomes, health-care utilization needs, workforce shortages, and costs.

Conclusion: A Call to Action

We have outlined a looming issue, a tsunami of survivors and a workforce gap, with respect to delivering follow-up care that will continue to affect all aspects of oncology practice unless addressed. Although other approaches may emerge, we advocate for development, testing, and implementation of a risk-stratified approach as a means to address this problem. Each group that is involved in providing follow-up care to survivors has a role in addressing these needs and gaps in care for survivors whose cancer treatment has ended. Stakeholders include professional organizations, cancer programs and health-care systems, individual clinicians and teams, patients and families, advocacy groups, health policy experts, and insurers. Some examples of critical actionable strategies for each are listed below.

Professional organizations should monitor and project workforce needs and provide the education, tools, and support needed to provide follow-up care for survivors. Creating risk-stratified, evidence-based care guidelines for clinicians and companion guidance for survivors needs to be developed collaboratively by our professional organizations to guide this effort. This should involve harmonizing our evidence-based, follow-up care recommendations as well as efforts to make them easily available, integrated, and actionable in our electronic health records to facilitate value-based cancer care. We also need to additionally define the metrics for quality survivorship care that will create accountability and incentives for delivering guideline-consistent care.

Cancer programs and health-care systems should analyze their patient characteristics and volumes as well as types of visits. Staffing, facilities, and programming needs should use types of patients (on treatment, off treatment) seen as well as the volume of visits and the number of patients. Transition plans for treating longer term, lower risk survivors in primary care should be developed and implemented. We need oncology clinicians to be setting the expectation from the time of cancer diagnosis that the patient should be continuing to see their PCP (or getting them one) throughout and beyond their cancer treatment for ongoing management of their other health issues. We also need to introduce “upfront” the idea that many patients will be followed by their PCP when treatment ends unless more oncology or other specialty care input is needed. New ways to support patients in self-managing their health are urgently needed as are ways to implement metrics for quality follow-up care to measure progress in meeting value-based quality cancer survivorship care. We also must leverage the growing number of eHealth programs, including electronic patient-reported outcome-based symptom surveillance and management systems to assist survivors in detecting new problems early. This system will be critical to the success of transitioning low-risk patients to self-management.

Patients and families should be actively engaged in their follow-up care and participating in supported self-management over time and to remain connected with their PCP throughout their cancer journey. We need to be sure we are finding interventions to meet survivors’ needs through eHealth or in their communities and with other available resources. For those who do not have the abilities, resources, or adequate social support to do so, alternative support will need to be provided.

Advocacy groups and other organizations can play a role in helping to develop materials and methods to support patients in self-managing their health, better using community resources/interventions (eg, LIVESTRONG at the YMCA) and eHealth interventions that can help with self-management outside the clinic (eg, ACS/National Cancer Institute-developed Springboard Beyond Cancer mobile health resource for survivors and caregivers). For survivors of intermediate or high risk, we need to create and test special follow-up clinics for those patients who do need specialized clinicians following them. These efforts need to rely on the use of advanced practice providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants), with oncologist input where needed, and seamless connections to a multi-disciplinary teams of clinicians who can help manage chronic and late effects (eg, cancer rehabilitation, psychosocial care, palliative care, cardio-oncology, genetics, etc.).

Clinicians need to help develop strategies enabling them to see a complex range of cancer patients while preventing burnout (55). How can oncologists maximize their satisfaction with a rewarding but emotionally difficult case load of patients? How can clinicians prepare patients and their families to be introduced to this idea early in the cancer process? How can they be supported to assume self-management during and after treatment ends? How do we facilitate patient-centered coordination of care among clinicians in meeting the needs of survivors? One example might be in scheduling follow-up patients for a separate time or clinic than new patients or patients on active treatment. Another example may be streamlining and reducing the burden of other tasks that prevent oncology clinicians from feeling a sense of purpose in their work. Programs to address work-life balance and coping strategies may also be beneficial to decompress intense work environments (56,57).

Health policy experts and insurance companies need to address the implications for this shift in follow-up care. We need to ensure adequate coverage for these services, especially in supporting survivors and their families in providing self-managed follow-up care. Clinicians should be reimbursed for working out plans for follow-up care with survivors and setting expectations for care.

Although risk-stratified cancer care has been suggested in the United States for over 10 years, little progress has been made in realizing this paradigm shift nor have alternative models emerged. As the growth of survivors continues and workforce shortages grow, we need to do more than write about this. As Craig Earle reminded us in 2006, failing to plan is planning to fail (58). We must start enacting plans to develop and test these new care models. Each stakeholder group should take on what they can do alone and collaborate with others to advance this agenda. Further, many of these ideas need to be developed and tested in a parallel process by several stakeholders brought together to create this shift in follow-up care. We hope this commentary will provide direction on what needs to be done to take this from concept to implementation. We simply cannot afford to fail. The health of our survivors, the happiness of our clinicians, and the financial well-being of our health-care systems and our patients and families are at stake.

Notes

Affiliations of authors: Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (DKM); School of Nursing, UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina (DKM); American Cancer Society, Inc (CAM).

DKM is a stockholder and advisor to CareVive. CAM has no disclosures.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and are not intended to reflect any official position of the National Cancer Institute.

The authors thank Drs Shelton Earp and Donald Rosenstein for their thoughtful critique of this commentary.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A.. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Facts & Figures 2016-2017. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mayer DK, Nasso SF, Earp JA.. Defining cancer survivors, their needs, and perspectives on survivorship health care in the USA. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):E11–E18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of clinical oncology breast cancer survivorship care guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):611–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen EE, LaMonte SJ, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society head and neck cancer survivorship care guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(3):203–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. El-Shami K, Oeffinger KC, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society colorectal cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(6):428–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Skolarus TA, Wolf AM, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(4):225–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nekhlyudov L, Ganz PA, Arora NK, et al. Going beyond being lost in transition: a decade of progress in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(18):1978–1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2018. Long-term survivorship care after cancer treatment: Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH.. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(7):1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(4):561–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elliott J, Fallows A, Staetsky L, et al. The health and well-being of cancer survivors in the UK: findings from a population-based survey. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(S1):S11–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fowler B, Ding Q, Pappas L, et al. Utah cancer survivors: a comprehensive comparison of health-related outcomes between survivors and individuals without a history of cancer. J Canc Educ. 2018;33(1):214–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R.. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(1):82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iadeluca L, Mardekian J, Chander P, et al. The burden of selected cancers in the US: health behaviors and health care resource utilization. CMAR. 2017; 9:721–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leach CR, Weaver KE, Aziz NM, et al. The complex health profile of long-term cancer survivors: prevalence and predictors of comorbid conditions. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(2):239–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Williams K, Jackson SE, Beeken RJ, et al. The impact of a cancer diagnosis on health and well-being: a prospective, population-based study. Psycho-Oncol. 2016;25(6):626–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hudson SV, Miller SM, Hemler J, et al. Adult cancer survivors discuss follow-up in primary care: ‘not what i want, but maybe what i need’. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(5):418–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cancer Stat Facts. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html. Accepted January 1, 2019.

- 21. de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(4):561–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, Tomlinson JS, et al. Wait times for cancer surgery in the United States: trends and predictors of delays. Ann Surg. 2011;253(4):779–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hortobagyi GN, American Society Of CO.. A shortage of oncologists? The American Society of Clinical Oncology workforce study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1468–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, et al. Future supply and demand for oncologists: challenges to assuring access to oncology services. JOP. 2007;3(2):79–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. The state of cancer care in America, 2014: a report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(2):119–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Center for Workforce Studies. Forecasting the Supply of and Demand for Oncologists: A Report to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) from the AAMC Center for Workforce Studies; 2007. http://dl4a.org/uploads/pdf/OncologyWorkforceReportFINAL.pdf. Accepted January 1, 2019.

- 27. Murali K, Banerjee S.. Burnout in oncologists is a serious issue: what can we do about it? Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;68:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Medisauskaite A, Kamau C.. Prevalence of oncologists in distress: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2017;26(11):1732–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Potosky AL, Han PK, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians' and oncologists' knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1403–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2016 to 2030: Final Report https://aamc-black.global.ssl.fastly.net/production/media/filer_public/bc/a9/bca9725e-3507-4e35-87e3-d71a68717d06/aamc_2018_workforce_projections_update_april_11_2018.pdf. Accepted January 1, 2019.

- 31. Kavilanz P. The US Can’t Keep up with Demand for Health Aides, Nurses and Doctors https://money.cnn.com/2018/05/04/news/economy/health-care-workers-shortage/index.html. Accepted January 1, 2019.

- 32. Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, et al. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zheng Z, Yabroff KR, Guy GP Jr, et al. Annual medical expenditure and productivity loss among colorectal, female breast, and prostate cancer survivors in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(5). djv382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP Jr, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(3):259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee Smith J, Hall IJ.. Advancing health equity in cancer survivorship: opportunities for public health. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(6)(suppl 5):S477–S482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brooks GA, Hoverman JR, Colla CH.. The affordable care act and cancer care delivery. Cancer J. 2017;23(3):163–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Johansen NJ, Saunders CM.. Value-based care in the worldwide battle against cancer. Cureus. 2017;9(2):e1039.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wheeler SB, Spencer J, Rotter J.. Toward value in health care: perspectives, priorities, and policy. N C Med J. 2018;79(1):62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Back AL, Deignan PF, Potter PA.. Compassion, compassion fatigue, and burnout: key insights for oncology professionals. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2014; E454–E459. doi:10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.e454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alfano CM, Leach CR, Smith TG, et al. Equitably improving outcomes for cancer survivors and supporting caregivers: a blueprint for care delivery, research, education, and policy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019; 69: 35–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jefford M, Rowland J, Grunfeld E, et al. Implementing improved post-treatment care for cancer survivors in England, with reflections from Australia, Canada and the USA. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(1):14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Richards M, Corner J, Maher J.. The National Cancer Survivorship Initiative: new and emerging evidence on the ongoing needs of cancer survivors. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(S1):S1–S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Long-Term Survivorship Care after Cancer Treatment: Proceedings of a Workshop; 2018. Washington (DC: ): National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jacobs LA, Shulman LN.. Follow-up care of cancer survivors: challenges and solutions. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):e19–e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nekhlyudov L, O'Malley DM, Hudson SV.. Integrating primary care providers in the care of cancer survivors: gaps in evidence and future opportunities. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):e30–e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS.. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117–5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macmillan Cancer Support. Evaluation of the Transforming Cancer Follow-up Programme in Northern Ireland Final Report https://www.macmillan.org.uk/documents/aboutus/research/researchandevaluationreports/ourresearchpartners/tcfufinalreportfeb2015.pdf. Accepted January 1, 2019.

- 48. Mittmann N, Beglaryan H, Liu N, et al. Examination of health system resources and costs associated with transitioning cancer survivors to primary care: a propensity-score-matched cohort study. J Oncol Pract. 2018;. JOP18.00275. doi:10.1200/JOP.18.00275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, et al. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(2):177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, et al. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(1):50–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Health Service. Stratified Pathways of Care – From Concept to Innovation https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/publication/stratified-pathways-of-care-from-concept-to-innovation/. Accepted January 1, 2019.

- 52.NHS Improving Quality. Stratified Cancer Pathways: Redesigning Services for Those Living With or Beyond Cancer. https://arms.evidence.nhs.uk/resources/qipp/1029456/attachment. Accepted January 1, 2019.

- 53. Alfano C, Mayer D, Bhatia S, et al. American Cancer Society – American Society of clinical oncology summit on implementing risk-stratified cancer follow-up care in the United States: key findings and recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2018; Under review. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Liu JL, Hlavka JP, Hillestad R, et al. Assessing the Preparedness of the U.S. Health Care System Infrastructure for an Alzheimer's Treatment https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2272.html. Accepted January 1, 2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55. Brand SL, Thompson Coon J, Fleming LE, et al. Whole-system approaches to improving the health and wellbeing of healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0188418.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jacobs B, McGovern J, Heinmiller J, et al. Engaging employees in well-being: moving from the triple aim to the quadruple aim. Nurs Adm Q. 2018;42(3):231–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH.. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Earle CC. Failing, to plan is planning to fail: improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5112–5116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]