Abstract

Background

Canadian youth are among the top users of cannabis globally. The Canadian federal government identified protecting youth from cannabis-related harms as a key public health objective aligned with the legalization and strict regulation of cannabis. While there are well-established associations between screen time sedentary behaviour (STSB) and alcohol and tobacco use, the association with cannabis use is understudied. The purpose of this study is to examine the association between various types of STSBs and cannabis use in a large sample of Canadian youth.

Methods

Using cross-sectional data from 46,957 grade 9 to 12 students participating in year 5 of the COMPASS host study (2016–2017), four gender-stratified ordinal logistic regression models were used to examine how total STSB and four different types of STSBs (watching/streaming TV shows/movies, playing video games, Internet use, emailing/messaging/texting) are associated with frequency of cannabis use.

Results

One-quarter of participants (24.9%) reported using cannabis in past 12 months; the largest proportion of this group (37.9%) reported rare/sporadic use. Overall, participants spent an average 7.45 ( ±5.26) hours/day on STSBs. Total STSB was positively associated with more frequent cannabis use, and when separated by type, internet use and messaging were significant. Playing video games and watching TV/movies were also significantly associated with more frequent cannabis use, but only for females.

Conclusions

The associations between frequency of cannabis use and various measures of STSBs suggest that screen time may be a risk factor for cannabis use among youth. This association may be mediated by youths’ mental wellbeing, given emerging evidence that STSB is a risk factor for poor mental health, and the tendency for individuals to use substances as a coping mechanism. Further, the ubiquity of pro-substance use content on the internet may also contribute to increased exposure to and normalization of cannabis, further promoting its use.

Keywords: Youth health, Substance use, Risk behaviours, Cannabis, Screen time

Highlights

-

•

Youth average of overall STSBs was 7.48 h per day.

-

•

Greater hours of overall STSB increased likelihood of higher frequency cannabis use.

-

•

Internet use and messaging STSBs were both positively associated with cannabis use.

-

•

Gender differences present for TV watching and video gaming STSBs.

-

•

Cyber-bullying victims show increased likelihood for higher frequency cannabis use.

1. Introduction

Cannabis use among Canadian youth is highly prevalent. Nationally-representative data from 2015 suggest that 28.9% of youth aged 15–19 years have used cannabis in their lifetime (Statistics Canada, 2018b), while a 2013/14 national survey reported that 13.0% of those aged 15 years reported use of cannabis within the past 30 days (World Health Organization, 2016). Two recent large cross-country studies identified that, across numerous measures of cannabis use, Canadian youth are among the top consumers of cannabis globally (UNICEF Office of Research, 2013; World Health Organization, 2016). The high prevalence of cannabis use among Canadian youth is concerning, since cannabis use is associated with a greater risk of poorer educational outcomes (Degenhardt et al., 2010; Meier, Hill, Small, & Luthar, 2015; Stiby et al., 2015), substance use disorders (Degenhardt et al., 2010) and poor mental health outcomes among adolescents, particularly when use is frequent, heavy, and initiated early in life (Brook, Brook, Zhang, Cohen, & Whiteman, 2002; Degenhardt, Hall, & Lynskey, 2003; Mackie et al., 2013). As such, efforts to prevent, delay and/or minimize cannabis use among Canadian youth represent an important public health priority.

There is currently considerable interest in cannabis use prevention initiatives targeting Canadian youth, given the Government of Canada's recent legalization in October 2018 and strict regulation of non-medical cannabis. In preparation for the legislative changes, the government's Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation developed a report highlighting the need for a public health approach to cannabis legalization and regulation, including strong efforts to protect youth and other vulnerable populations from the harms associated with cannabis use (Government of Canada, 2016). The report includes recommendations for the federal government to monitor and restrict cannabis-related advertising and marketing, including traditional and social media, as well as specific efforts to protect youth from exposure to mass marketing and advertising of cannabis products (Government of Canada, 2016).

Decades of public health research on the risk factors for tobacco and alcohol use provide strong evidence that exposure to substance-related marketing efforts is associated with a greater probability of substance use (Anderson, de Bruijn, Angus, Gordon, & Hastings, 2009; Lovato, Watts, & Stead, 2011). Likewise, a recent American longitudinal study found that exposure to advertisements for cannabis products was predictive of a higher probability of later cannabis use among adolescents (D'Amico, Miles, & Tucker, 2015). However, since cannabis has long been an illegal substance, there has been limited research to date on the presence and influence of cannabis-related content in mainstream marketing efforts. These insights would help to inform regulation and restrictions of cannabis marketing, particularly in light of its new legal status in Canada.

Youth are exposed to contemporary marketing efforts, including those related to substances, via diverse media forms (e.g., print media, film, music, social media, video games, and websites). For instance, substances and substance use are commonly featured in media popular among youth, including film and social media websites and applications (Moreno et al., 2010; Morgan, Snelson, & Elison-Bowers, 2010; Stern & Morr, 2013), where they are often portrayed in a positive light. In particular, cannabis-related social media tends to be pro-use in nature (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2015; Cavazos-Rehg, Krauss, Sowles, & Bierut, 2016; Krauss, Sowles, Stelzer-Monahan, Bierut, & Cavazos-Rehg, 2017; L.; Thompson, Rivara, & Whitehill, 2015), which may normalize and glamorize its use among those exposed to these media. Further, in Canada and other parts of the world, children and adolescents regularly spend considerable time on devices such as mobile phones and computers, and screen time sedentary behaviours (STSBs) (e.g. using the internet, playing computer games, watching/steaming TV/movies) (S.T. Leatherdale & Ahmed, 2011; Minges et al., 2015). Given the difficulty in directly measuring exposure to specific media content, research often uses STSBs as an indicator of media exposure, as it is plausible that use of such devices, and the corresponding marketing and media exposure, represents an important risk factor for substance use among youth (Carson, Pickett, & Janssen, 2011; Russ, Larson, Franke, & Halfon, 2009).

Indeed, an emerging body of research has identified an association between media exposure from STSBs and substance use among children and adolescents (Nunez-Smith et al., 2010). A Canadian study found that excessive screen time in adolescents was positively associated with frequency of cannabis use, as well as other risk behaviours (Carson et al., 2011). Likewise, another study identified that adolescents’ engagement in frequent electronic media communication (i.e., phone calls, instant messaging, text messaging, emails) with friends is associated with a variety of substance use behaviours, including cannabis use (Gommans et al., 2015). Evidence from the alcohol literature suggests that the association between media exposure and substance use behaviours may be moderated by peer norms (Nesi, Rothenberg, Hussong, & Jackson, 2017). However, the mechanisms by which media exposure is associated with cannabis use are not well-understood, and there has been limited inquiry on how this association varies by media form, particularly in the Canadian context.

The primary objective of this study is to examine the association between STSBs and frequency of cannabis use among a large sample of Canadian secondary school-aged students. Secondary objectives include to investigate how different forms of STSBs are associated with cannabis use, and to explore possible associations between STSBs, cannabis use and two vulnerable populations: Indigenous youth and victims of cyber-bullying. These two populations may be uniquely vulnerable to cannabis use, as Indigenous youth in Canada have a higher prevalence of cannabis use compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts (Elton-Marshall, Leatherdale, & Burkhalter, 2011) and there is some evidence for an association between peer victimization (including cyberbullying) and cannabis use (Maniglio, 2015). Overall, this study may help to inform the targets and nature of cannabis media regulations intended to protect youth that are in development in Canada, and other jurisdictions that are soon to liberalize their cannabis policies.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

The COMPASS host study is an ongoing prospective cohort study (2012–2021) of a convenience sample of secondary school students in four provinces and one territory in Canada (Ontario, Alberta, British Columbia, Quebec, and Nunavut). The study collects longitudinal, hierarchal data to examine the influence of the school environment on student health outcomes including physical activity, healthy eating, bullying, and tobacco, alcohol and marijuana use. Self-reported data are obtained through questionnaires administered during class time, using an active-information passive consent parental permission protocol. As the present study examines substance use behaviour in youth (cannabis use), the use of this passive consent protocol is important to limit selection bias (Rojas, Sherrit, Harris, & Knight, 2008; Thompson-Haile, Bredin, & Leatherdale, 2013). The COMPASS study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Board at the University of Waterloo. A full description of the COMPASS host study is available in print (Scott T Leatherdale et al., 2014) or online (www.compass.uwaterloo.ca).

2.2. Participants

Of the 60,620 students eligible and recruited to participate in year 5, 46,957 participated (77.46%); 0.18% students did not participate because they were withdrawn from participation by a parent/guardian, and 22.54% were eligible to participate, but did not. Non-participation by eligible participants is typically due to absence from school on the data collection date or having a free period during class during which the data collection occurred. In year 5, 72.6% of the sample was in Ontario, 6.4% was in Alberta, 7.7% was in British Columbia, 13.2% was in Quebec, and 0.2% was in Nunavut. The present study uses complete case analysis, and as such a total of 44,011 individuals were included in analysis.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Dependent variable

Cannabis use frequency was assessed based on response to the following question: “In the last 12 months, how often did you use marijuana or cannabis? (a joint, pot, weed, hash)” where the options are: “I have never used marijuana,” “I have used marijuana but not in the last 12 months,” “Less than once a month,” “Once a month,” “2 to 3 times a month,” “Once a week,” “2 or 3 times a week,” “4 to 6 times a week,” and “Every day.” These options were regrouped as follows. Anyone who indicated “I have never used marijuana” or “I have used marijuana but not in the last 12 months,” was classified as a non-user. Those who indicated “Less than once a month” were classified as rare/sporadic users. This measure is consistent with nationally representative surveillance of youth substance use in Canada (Burkhalter, Cumming, Rynard, Schonlau, & Manske, 2018, pp. 2010–2015). Individuals who indicated “Once a month” or “2 to 3 times a month” were considered monthly users. Those who responded “Once a week,” “2 or 3 times a week,” or “4 to 6 times a week” were classified as weekly users. Anyone who indicated “Every day” was considered a daily user.

2.3.2. Independent variables of interest

The measures of STSBs were derived from the question “How much time per day do you usually spend doing the following activities?” where the four items of interest were “Watching/streaming TV shows or movies,” “Playing video/computer games,” “Surfing the internet,” and “texting, messaging, emailing (note: 50 texts = 30 min).” Individuals indicated their response to each item by choosing number of hours (ranging from 0 to 9) and minutes (ranging from 0 to 45). This measure of STSB has been validated for use in youth (S.T. Leatherdale, Laxer, & Faulkner, 2014). Consistent with previous research, the aforementioned STSBs are assumed to by definition be sedentary. However, it is possible that some activities could be active (e.g. watching TV while running on a treadmill), and as such STSB is not used an indicator of physical inactivity in this manuscript. For each item, the number of hours and minutes were summed, resulting in four continuous variables representing time spent engaged in discrete STSBs. A measure of overall STSB was created by summing the four discrete measures of STSBs, and represents the fifth continuous independent variable of interest. For interpretability, the scale for these continuous variables is such that one unit is equal to 60 min. Since each category of screen time is not necessarily mutually exclusive (i.e., participants can be engaged in numerous STSBs simultaneously), mean values for overall STSB time should be interpreted with caution.

2.3.3. Additional covariates

Other covariates included three known correlates of cannabis use among youth, including binge drinking (rare/sporadic, monthly, weekly/daily), smoking status (non-smoker, smoker), and classes skipped over a 4-week time period (0, 1–5, 6+), as well as four potential confounders, including province (Ontario, Alberta, British Columbia, Quebec, Nunavut), grade (9,10,11,12), ethnicity (White, Asian, Black, Aboriginal (First Nations, Metis, Inuit), Latin American/Hispanic, or Other), and spending money per week ($0-$20, $21 - $40, $41 - $100, > $100, I don't know). Cyber bullying was also included as an additional covariate of interest and assessed using the question “In the last 30 days, in what ways were you bullied by other students?” where the option of interest was “Cyber-attacks (e.g., being sent mean text messages or having rumours spread about you on the internet).” Using the response to this question, a binary measure of experience of cyber bullying (yes, no) was created.

2.4. Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4. Basic descriptive statistics were used to obtain demographic information, and chi-square and ANOVA tests individually compared the outcome variable, cannabis use frequency, to all predictor variables. Four ordinal logistic regression models stratified by gender were run using the PROC GENMOD procedure. Measurements of cannabis use frequency on an ordinal scale is consistent with existing substance use research (Spechler et al., 2018; White, Walton, & Walker, 2015a, 2015b). Pairwise slope analyses justified the use of an ordinal outcome with the proportional odds assumption in these models. All models contain the same covariates but differ with respect to STSB variables included. Unstratified models which controlled for gender were tested, and the results align with those of the stratified models. Only the stratified models are presented to allow for examination of gender differences. Models 1 and 2 assess STSB using the collective measure that sums all four STSBs into one overall measure of STSB hours in females and males, respectively. Models 3 and 4 separate STSB by the four types in order to test whether the different types of media have different effects on the outcome in females and males, respectively. Interactions between measures of STSB and cyber-bullying were tested, but were not found to be significant and are not presented. Reference groups were consistent across all models and were chosen to allow for valuable interpretation. The empirical results are presented.

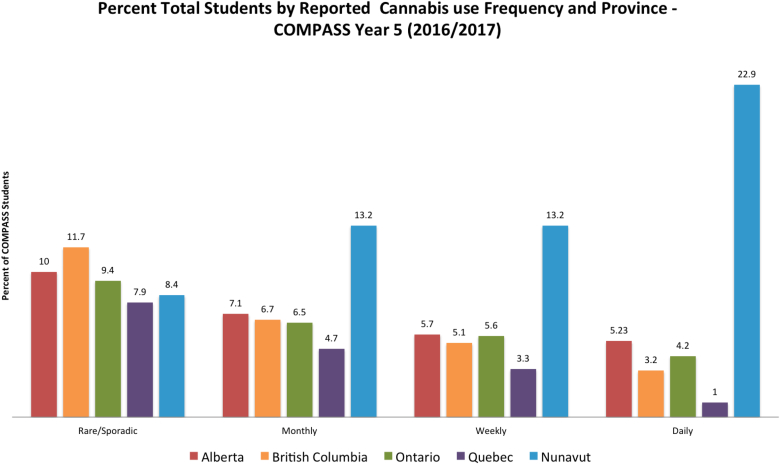

3. Results

In this sample, 24.9% of participants reported at least some level of cannabis use within the past 12 months. The largest proportion of these participants (37.9%) reported rare/sporadic use, while monthly (25.5%), weekly (21.3%), and daily (15.3%) cannabis use was reported less frequently. Fig. 1 shows the proportions of reported cannabis use frequencies by province in our sample. Cannabis use frequencies varied by province (degrees of freedom [df] = 8, p < .0001); Nunavut had the highest proportion of monthly (13.2%), weekly (13.2%), and daily users (22.9%). Alberta trailed Nunavut in the more frequent use categories, with 5.7% of the sample reporting weekly use, and 5.2% reporting daily use. Positive associations between cannabis use and other substance use behaviors (smoking, binge drinking) were present.

Fig. 1.

This graph shows the percentage of COMPASS students from Year 5 (2016/2017) who reported cannabis use in the past 12 months, by frequency and by province.

Mean overall STSB hours was significantly greater with higher levels of cannabis use frequency (p < .0001). For example, those who reported daily cannabis use reported a mean of 12.56 h of total STSB, compared to a mean of 6.93 h among those who reported no cannabis use. A similar pattern was evident for each type of STSB considered separately (p < .0001 for all four). Only 3.9% of participants who reported no cannabis use reported being a victim of cyber-bullying with the last month, while 15.5% of participants who reported daily cannabis use reported being a victim of cyber-bullying (df = 4, p < .0001) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics by cannabis use frequencies, COMPASS study year 5 (2016–2017).

| Variables | Cannabis Use Frequency % (N) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N = 45208 |

Non-Users N = 33949 |

Rare/Sporadic Users N = 4263 |

Monthly Users N = 2876 |

Weekly Users N = 2399 |

Daily Users N = 1721 |

CHI SQUARED/ANOVA | ||

| Gender | Df = 4, p < .0001 | |||||||

| Female | 50.0 (22588) | 50.9 (17265) | 55.0 (2346) | 49.7 (1428) | 41.4 (993) | 32.3 (556) | ||

| Male | 50.0 (22620) | 49.1 (16684) | 45.0 (1917) | 50.3 (1448) | 58.6 (1406) | 67.7 (1165) | ||

| Grade | Df = 16, p < .0001 | |||||||

| 9 | 25.6 (11562) | 29.7 (10088) | 12.6 (536) | 13.6 (392) | 13.1 (314) | 13.5 (232) | ||

| 10 | 26.7 (12063) | 26.9 (9141) | 25.3 (1080) | 26.9 (775) | 27.9 (670) | 23.1 (397) | ||

| 11 | 24.1 (10900) | 21.8 (7407) | 32.5 (1385) | 31.1 (895) | 29.4 (705) | 29.5 (508) | ||

| 12 | 18.2 (8221) | 14.8 (5015) | 28.2 (1204) | 26.8 (772) | 27.7 (665) | 32.8 (565) | ||

| Othera | 5.5 (2462) | 6.8 (2298) | 1.4 (58) | 1.5 (42) | 1.9 (45) | 1.1 (19) | ||

| Ethnicity | Df = 20, p < .0001 | |||||||

| White | 71.4 (32168) | 71.7 (24273) | 76.1 (3241) | 73.5 (2108) | 69.5 (1662) | 51.5 (884) | ||

| Black | 3.9 (1776) | 3.6 (1218) | 3.0 (129) | 4.1 (118) | 4.6 (111) | 11.6 (200) | ||

| Asian | 6.5 (2905) | 7.5 (2550) | 3.0 (128) | 3.5 (101) | 2.6 (61) | 3.8 (65) | ||

| Latin American/Hispanic | 3.4 (1514) | 2.5 (855) | 3.8 (161) | 5.5 (158) | 7.3 (175) | 9.6 (165) | ||

| Aboriginal (First Nations, Métis, Inuit) | 2.6 (1152) | 2.5 (861) | 2.3 (98) | 3.0 (85) | 2.3 (54) | 3.1 (54) | ||

| Otherb | 12.3 (5553) | 12.1 (4077) | 11.7 (500) | 10.4 (298) | 13.8 (329) | 20.3 (349) | ||

| Spending Money (per week) | Df = 16, p < .0001 | |||||||

| $0 - $20 | 42.8 (19254) | 47.3 (15966) | 30.9 (1314) | 28.7 (821) | 29.3 (699) | 26.6 (454) | ||

| $21 - $40 | 11.3 (5071) | 11.0 (3713) | 11.4 (482) | 12.4 (356) | 13.7 (326) | 11.4 (194) | ||

| $41 - $100 | 13.5 (6079) | 12.3 (4137) | 17.8 (756) | 19.0 (545) | 17.2 (411) | 13.5 (230) | ||

| > $100 | 18.6 (8361) | 14.5 (4895) | 28.6 (1216) | 30.6 (876) | 30.2 (721) | 38.2 (653) | ||

| I don't know | 13.8 (6181) | 14.9 (5028) | 11.3 (478) | 9.3 (267) | 9.6 (230) | 10.4 (178) | ||

| Classes Skipped (in previous 4 weeks) | Df = 8, p < .0001 | |||||||

| 0 | 67.9 (30316) | 76.9 (25839) | 49.0 (2068) | 40.6 (1155) | 33.7 (793) | 27.8 (461) | ||

| 1–5 | 26.8 (11983) | 20.6 (6912) | 44.4 (1874) | 49.1 (1398) | 51.1 (1201) | 36.1 (598) | ||

| 6+ | 5.3 (2353) | 2.5 (830) | 6.5 (276) | 10.3 (292) | 15.2 (358) | 36.1 (597) | ||

| Smoking Status | Df = 4, p < .0001 | |||||||

| Nonsmoker | 89.1 (40200) | 97.1 (32905) | 83.3 (3542) | 67.1 (1923) | 53.0 (1266) | 33.1 (564) | ||

| Smoker (past 30 day use) | 10.9 (4904) | 2.9 (987) | 16.7 (712) | 32.9 (943) | 47.0 (1122) | 66.9 (1140) | ||

| Binge Drinking | Df = 12, p < .0001 | |||||||

| Never | 63.3(28511) | 77.7 (26312) | 23.4 (992) | 19.2 (551) | 17.4 (414) | 14.2 (242) | ||

| Rare/Sporadic | 16.1(7250) | 12.8 (4347) | 35.8 (1520) | 23.1 (660) | 20.1 (480) | 14.3 (243) | ||

| Monthly | 15.2(6870) | 8.0 (2706) | 33.7 (1433) | 43.2 (1238) | 41.9 (1000) | 28.9 (493) | ||

| Weekly/daily | 5.4(2442) | 1.5 (509) | 7.1 (302) | 14.4 (414) | 20.5(490) | 42.6 (727) | ||

| Experienced Cyber Bullying | Df = 4, p < .0001 | |||||||

| No | 94.7 (42814) | 96.1 (32612) | 92.6 (3949) | 91.2 (2622) | 90.7 (2176) | 84.5 (1455) | ||

| Yes | 5.3 (2394) | 3.9 (1337) | 7.4 (314) | 8.8 (254) | 9.3 (223) | 15.5 (266) | ||

| Overall STSB (hours/day) (mean, SD) | 7.45 (5.26) | 6.93 (4.76) | 7.75 (4.66) | 8.75 (5.30) | 9.17 (5.65) | 12.56 (9.89) | p < .0001 | |

| STSBs by Types (hours/day) (mean, SD) | ||||||||

| Watching/Streaming TV Shows/Movies (mean, SD) | 1.99 (1.62) | 1.92 (1.53) | 1.97 (1.43) | 2.14 (1.60) | 2.19 (1.68) | 3.07 (2.86) | p < .0001 | |

| Playing Video Games (mean, SD) | 1.32 (1.96) | 1.32 (1.92) | 0.95 (1.60) | 1.08 (1.70) | 1.38 (1.97) | 2.45 (3.08) | p < .0001 | |

| Internet Use (mean, SD) | 2.12 (2.11) | 1.96 (1.99) | 2.30 (2.03) | 2.58 (2.24) | 2.67 (2.34) | 3.41 (3.13) | p < .0001 | |

| Messaging (mean, SD) | 2.02 (2.27) | 1.73 (2.06) | 2.53 (2.33) | 2.95 (2.55) | 2.93 (2.59) | 3.63 (3.34) | p < .0001 | |

Includes individuals who are in a class with no official grade or grade equivalent.

Includes individuals who specified “Other” ethnicity on the questionnaire, as well as those who indicated more than one ethnicity.

Table 2 presents the results of the four ordinal logistic regression models. Overall direction and magnitude of associations presented align with that of unstratified models, but only the stratified models are presented here to allow for examination of gender differences. Notably, as the outcome is ordinal, our interpretation of ‘more frequent cannabis use’ refers to the likelihood of rare/sporadic use compared to non-use, but also refers to higher levels of use among users (i.e. the likelihood of reporting monthly use compared to rare/sporadic use, weekly use compared to monthly use, and daily use compared to weekly use). In model 1 (females), which used the measure of overall STSB, the two substance use behaviors: binge drinking (rare/sporadic: OR 5.31, 95% CI 4.75–5.94, monthly: OR 8.99, 95% CI 7.80–10.37, weekly/daily: OR 15.12, 95% CI 12.41–18.42) and smoking (OR 5.66, 95% CI 4.92–6.52), were significantly associated with likelihood of more frequent cannabis use. Number of classes skipped in the past 4 weeks (1–5: OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.77–2.13, 6+: OR 3.51, 95% CI 3.02–4.09) was also significantly associated with likelihood of more frequent cannabis use. These aforementioned results, as well as the control variables from model 1, were consistent with the results of model 2, which examined the same relationship in males. These results were also consistent with models 3 and 4, which examined STSB by type among males and females respectively.

Table 2.

Results of cannabis frequency ordinal logistic regression models by gender, COMPASS study year 5 (2016–2017).

| Variables | Proportional Odds Ratios (95% CI) (N = 44,011) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (Females) | Model 2 (Males) | Model 3 (Females) | Model 4 (Males) | |

| Grade | ||||

| 9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 10 | 1.58 (1.35–1.86)*** | 1.30 (1.12–1.51)*** | 1.58 (1.35–1.86)*** | 1.30 (1.12–1.51)** |

| 11 | 1.73 (1.46–2.04)*** | 1.35 (1.16–1.57)*** | 1.73 (1.46–2.04)*** | 1.34 (1.15–1.56)*** |

| 12 | 1.71 (1.44–2.02)*** | 1.51 (1.28–1.78)*** | 1.71 (1.44–2.03)*** | 1.51 (1.28–1.77)*** |

| Other | 0.71 (0.44–1.14)*** | 0.64 (0.43–0.94)* | 0.71 (0.44–1.14) | 0.65 (0.44–0.96)* |

| Classes Skipped (in previous 4 weeks) | ||||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1–5 | 1.94 (1.77–2.13)*** | 1.77 (1.60–1.96)*** | 1.94 (1.77–2.13)*** | 1.76 (1.59–1.95)*** |

| 6+ | 3.51 (3.02–4.09)*** | 3.78 (3.16–4.52)*** | 3.50 (3.00–4.07)*** | 3.78 (3.15–4.52)*** |

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Nonsmoker | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Smoker (past 30 day use) | 5.66 (4.92–6.52)*** | 4.90 (4.30–5.59)*** | 5.64 (4.90–6.50)*** | 4.87 (4.27–5.56)*** |

| Binge Drinking | ||||

| Never | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Rare/Sporadic | 5.31 (4.75–5.94)*** | 6.07 (5.47–6.73)*** | 5.32 (4.75–5.95)*** | 5.96 (5.37–6.62)*** |

| Monthly | 8.99 (7.80–10.37)*** | 8.85 (7.85–9.98)*** | 9.02 (7.82–10.39)*** | 8.62 (7.62–9.74)*** |

| Weekly/daily | 15.12 (12.41–18.42)*** | 14.57 (12.35–17.19)*** | 15.11 (12.40–18.42)*** | 14.19 (12.00–16.76)*** |

| Experienced Cyber Bullying | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.35 (1.20–1.52)*** | 1.40 (1.15–1.69)*** | 1.31 (1.14–1.51)*** | 1.28 (1.00–1.65) |

| Overall STSB (hours/day) | 1.05 (1.05–1.06)*** | 1.03 (1.02–1.04)*** | ||

| STSBs by Type (hours/day) | ||||

| Watching/Streaming TV Shows/Movies | 1.04 (1.01–1.07)* | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | ||

| Playing Video Games | 1.06(1.03–1.09)*** | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | ||

| Internet Use | 1.06(1.04–1.08)*** | 1.04 (1.02–1.06)** | ||

| Messaging | 1.05 (1.04–1.07)*** | 1.05 (1.03–1.08)*** | ||

*p < .05 **p < .01 ***p < .001.

All models controlled for province/territory of data collection, reported ethnicity, and reported spending money per week.

In model 1 (females), the overall measure of STSB was positively associated with cannabis use frequency, whereby every additional hour increase in overall STSB significantly increased the likelihood of more frequent cannabis use by 5% (OR 1.05, 95% CI 1.05–1.06). In model 2 (males) the results were similar; overall STSB significantly increased the likelihood of more frequent cannabis use by 3% (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.04). Models 3 and 4 examined STSB separated by type among females and males, respectively. The results of model 3 indicated that all 4 STSBs were significantly were associated with more frequent cannabis use. In model 4, internet use (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02–1.06) and messaging (OR 1.05, 95% CI 1.03–1.08) were both significantly associated with more frequent cannabis use, while video games (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.99, 1.03) and watching/streaming TV shows/movies (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.99–1.04) were not.

Model 1 demonstrated a positive association between cyber-bullying victimization and likelihood of more frequent cannabis use (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.20–1.52), and model 2 showed a similar association among males (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.15–1.69). Model 3 was relatively consistent with model 1 in regard to the effect of cyber bullying (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.14–1.51), however model 4 indicated that this association was not significant among males (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.00–1.65) after accounting for the different types of STSBs.

4. Discussion

This study examined patterns of cannabis use and STSBs, as well as the associations between these behaviours, among a large sample of Canadian youth. We found that more time spent on STSBs was associated with more frequent cannabis use, though the extent of these associations differs by gender. These findings may reflect untested associations between STSBs and poor mental health, (a risk factor for problematic substance use), and the ubiquity of pro-use content online, and have important implications for future research and public health policy. Future research should examine if mental health is associated with STSB and cannabis use, and how these associations change over time. Additional research is also warranted to more fully explore the positive correlation identified between experiences of cyber-bullying and cannabis use in order to inform intervention efforts to protect marginalized youth.

Consistent with previous research (Health Canada, 2012; UNICEF Office of Research, 2013), one-quarter of participants in this sample reported cannabis use. Nearly 40% of cannabis users in this sample were using in the rare/sporadic category, where participants reported their cannabis use was less than once a month. Consistent with previous research (Government of Canada. (n.d.).), there were important regional differences in participants’ cannabis use across the five provinces and territories; Nunavut showed the highest rates of high frequency cannabis use, followed by Alberta, while Quebec showed the lowest rates of any level of use.

This study's findings suggest that STSBs are a risk factor for cannabis use among youth. Participants in this sample reported a total average of 7.45 h per day of STSB, which substantially exceeds Canada's screen time guidelines for this age group (recommending <2 h per day) (Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology, 2012). The present study showed that for each additional hour of average STSB, the likelihood of more frequent cannabis use increased by 5% for males, and 3% for females. Importantly, these results are additive; for example, an additional 2 h of average STSB would be associated with a 10% increase in likelihood of more frequent cannabis use for males, and 6% for females. Although associations with mental health variables was not tested in this manuscript, it is possible that the effects of STSBs on propensity for cannabis use seen in the present study may be mediated by mental health status and wellbeing. Previous research has established connections between greater screen time and poorer mental health outcomes in youth, driven by numerous potential mechanisms such as increased social isolation, and poor levels of sleep and/or physical activity (Lissak, 2018; Maras et al., 2015; Trinh, Wong, & Faulkner, 2015). In turn, negative mental health outcomes have been associated with substance use behaviours (Goodman, 2010; K.; Thompson, Merrin, Ames, & Leadbeater, 2018). The numerous government and school-level initiatives aiming to increase youth's physical activity and decrease sedentary behaviour would be complemented by additional population-level efforts to decrease excessive STSBs and bolster overall wellbeing among adolescents. Comprehensive school-based initiatives are well-poised to address these objectives, including through efforts to improve students' media literacy, enhance social and emotional learning skills, and foster school connectedness. Future research examining associations between mental health and wellbeing-related outcomes and cannabis use would help to inform and lend support to this more upstream means of preventing substance use related harms.

Models 3 and 4 demonstrate that internet use and messaging are associated with more frequent cannabis use for both males and females in this sample. While internet use can encompass a wide variety of activities, Statistics Canada (Statistics Canada, 2018a) reports that 96% of Canadian youth and young adults use social media sites, and social media may take up a large portion of internet time, as the majority of users visit the sites daily or more (Common Sense Media, 2012; Gruzd, Jacobson, Mai, & Dubois, 2018, pp. 1–18). Engagement with pro-use content on social media has been associated with real-life alcohol (Carrotte, Dietze, Wright, & Lim, 2016; Huang et al., 2014) and tobacco use (Depue, Southwell, Betzner, & Walsh, 2015; Huang et al., 2014) in adolescents and young adults, as this content contributes to the normalization of substance use behaviours. This research may indicate that similar associations apply to cannabis use, as previous research has identified that the majority of cannabis use content online is pro-use in nature (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2016, 2015; Krauss et al., 2017; L.; Thompson et al., 2015) However, more research that directly analyzes this association is necessary; while social media use and internet use likely overlap substantially for this age group, they are distinct entities.

Accurate information related to cannabis use, including potential harms within an adolescent population, is essential in Canada given legalization. A 2016 study found that the majority of Colorado cannabis retailers make unregulated claims about the health benefits of cannabis on their websites (Bierut, Krauss, Sowles, & Cavazos-Rehg, 2017), and this mixed/inaccurate messaging, coupled with the pro-use content on social media, may confuse youth about the hazards of cannabis uptake at a young age (Menghrajani, Klaue, Dubois-Arber, & Michaud, 2005). Canada's legalization framework has recommended that marketing/advertising violations, including those on social media, be enforced by the federal government; however the rules governing social media or online advertising are not outlined (Government of Canada, 2016). Previous research has cautioned that the legal cannabis industry is unlikely to self-regulate their marketing at the expense of profit (Budney & Borodovsky, 2017), and urged governments moving forward with cannabis legalization to apply lessons from alcohol and tobacco to guide restrictions related to the marketing of cannabis products (Barry & Glantz, 2016; Budney & Borodovsky, 2017). The federal government has been active in its public education efforts (including those on social media platforms) in preparation for and following cannabis legalization. For example, the Canadian government launched a social media-#dontdrivehigh campaign focused on increasing awareness about the risks associated with drugged-driving (Government of Canada, 2018). These efforts may be well positioned to reach youth, given our findings that youth tend to have high average STSB per day, and that greater STSBs, including internet use, increases the likelihood of more frequent cannabis use. Additional efforts to disseminate cannabis related information on social media as a harm-reduction approach may be beneficial. Media campaigns and other public education efforts on the social and health risks of cannabis use are important to prevent the further normalization and glamorization of cannabis use, as it is important to ensure that cannabis does not progress towards the same level of normalization as alcohol use. However, public education must be coupled with efforts to reduce the stigmatization of substance use in order to foster open, evidence-informed dialogues about substance use and encourage help seeking for those with problematic substance use.

The stratified models presented highlight some interesting gender differences related to STSBs. Watching/streaming TV shows/movies and playing video games were both significantly associated with increased likelihood of more frequent cannabis use for females, but not for males. As video gaming is an activity more normalized for males (DeCamp, 2017), it is possible that the stratified results of the present study reflect that females with high video gaming hours tend to be a more homogenous group with a higher propensity for cannabis use, whereas males with high video gaming hours are a more heterogenous group with greater variety in patterns of substance use. However, more research is needed in this area, as the results of previous research of substance use and video games has been inconsistent (Coëffec et al., 2015; van Rooij et al., 2014). On the other hand, numerous studies have indicated that viewing TV shows or movies depicting alcohol and/or tobacco use is associated with increased likelihood of engaging in that corresponding behaviour (Hanewinkel et al., 2012; Morgenstern et al., 2013); the findings of the present study may identify that similar patterns exist for cannabis use, although in this sample only among females.

In addition to the STSB findings, gender differences were also present in our findings related to cyber-bullying. After accounting for the different types of STSB, being a victim of cyber bulling was significantly associated with increased likelihood of more frequent cannabis use for females, but not for males. Research has highlighted that unlike other types of bullying, females are more likely to be cyber-bullied than their male counterparts (Mishna, Khoury-Kassabri, Gadalla, & Daciuk, 2012), which may partly explain the present findings. Connection between experiences of bullying and cannabis use is supported by previous literature, highlighting connections between experiences of bullying, mental wellbeing, and substance use (Earnshaw et al., 2017; Maniglio, 2015), although this topic is understudied. In this study female participants who reported daily cannabis use also reported the highest proportion of experiences cyber-bullying, which may reflect that victims are using cannabis as to help cope with their experience of bullying.

5. Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include its large sample size, use of passive consent protocol, and timely examination of youth cannabis use in a Canadian context. This study also added to the limited body of research examining STSB and substance use in youth, and can serve as a pre-legalization baseline for future comparisons. There are a number of important limitations to note in this study. First, this study was cross-sectional, and therefore temporal associations cannot be established, and thus it is possible that the results of the present study, and of previous cross-sectional research, are subject to reverse causality. We posit here that greater STSB is associated with an increased likelihood of more frequent cannabis use; however, it is also plausible that more frequent cannabis users spend more time engaging in STSBs. The reality is likely a complex combination of relationships that work in both directions., and future directions for this research should include examination of longitudinal patterns. Second, mental health variables may play a key role in identifying the mechanism by which STSB and cannabis use are associated, but mental health data was not available for inclusion in this analysis, and conclusions may be changed with their inclusion. For example, if mental health acts as a mediator, its inclusion may attenuate associations observed between STSB and cannabis use. Third, the data used in the present study were self-report data, and therefore may be subject to response biases. This study also had some degree of unit non-response, and it is possible that there are systematic differences between participants and non-participants which may limit the generalizability of the findings. However, this limitation is mitigated as much as is feasible through the use of a passive consent procedure in the study design. Lastly, our sample contains non-representative data from five provinces, and thus the results presented cannot be used to make associations in other jurisdictions.

6. Conclusion

Cannabis use in this sample was common, with one-quarter of youth reporting at least some level of cannabis use within the past 12 months. This study found that as time spent engaged in STSBs increased, so did likelihood of more frequent cannabis use. Of the types of STSBs examined, internet use and messaging were significantly associated with more frequent cannabis use in males and females, which may be partly explained by STSB's impact on wellbeing, and/or exposure to pro-cannabis content on the internet. The results of this study highlight that efforts to limit the negative effects of STSBs on youth are needed. While this research added to the existing knowledge gap, the effects of STSBs on cannabis use remains understudied. Future research should continue to examine these relationships, particularly in a Canadian context.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

The COMPASS study has been supported by a bridge grant from the CIHR Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes (INMD) through the “Obesity – Interventions to Prevent or Treat” priority funding awards (OOP-110788; grant awarded to Scott T. Leatherdale), an operating grant from the CIHR Institute of Population and Public Health (IPPH) (MOP-114875; grant awarded to Scott T. Leatherdale), a CIHR Project Grant (PJT-148562; grant awarded to Scott T. Leatherdale), a CIHR Project Grant (PJT-149092; grant awarded to Karen Patte), and by a research funding arrangement with Health Canada (#1617-HQ-000012; contract awarded to Scott T. Leatherdale). The creation of this manuscript was funded by the Research Affiliate Program from the Public Health Agency of Canada, Applied Research Branch.

Ethics approval statement

The University of Waterloo Office of Research Ethics reviewed and approved all aspects of the study protocol.

References

- Anderson P., de Bruijn A., Angus K., Gordon R., Hastings G. Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2009;44(3):229–243. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry R.A., Glantz S. A public health framework for legalized retail marijuana based on the US experience: Avoiding a new tobacco industry. PLoS Medicine. 2016;13(9):e1002131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut T., Krauss M.J., Sowles S.J., Cavazos-Rehg P.A. Exploring marijuana advertising on weedmaps, a popular online directory. Prevention Science. 2017;18(2):183–192. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0702-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook D.W., Brook J.S., Zhang C., Cohen P., Whiteman M. Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney A.J., Borodovsky J.T. The potential impact of cannabis legalization on the development of cannabis use disorders. Preventive Medicine. 2017;104:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhalter R., Cumming T., Rynard V., Schonlau M., Manske S. Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, University of Waterloo; Ontario: 2018. Research methods for the Canadian student tobacco, alcohol and drugs survey, 2010-2015. Waterloo. (April) [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology . 2012. Canadian sedentary behaviour guidelines.http://www.csep.ca/CMFiles/Guidelines/CanadianSedentaryGuidelinesStatements_E_2012.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Carrotte E.R., Dietze P.M., Wright C.J., Lim M.S. Who ‘likes’ alcohol? Young Australians' engagement with alcohol marketing via social media and related alcohol consumption patterns. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2016;40(5):474–479. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson V., Pickett W., Janssen I. Screen time and risk behaviors in 10- to 16-year-old Canadian youth. Preventive Medicine. 2011;52(2):99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg P.A., Krauss M., Fisher S.L., Salyer P., Grucza R.A., Bierut L.J. Twitter chatter about marijuana. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;56(2):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg P.A., Krauss M.J., Sowles S.J., Bierut L.J. Marijuana-related posts on instagram. Prevention Science. 2016;17(6):710–720. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0669-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coëffec A., Romo L., Cheze N., Riazuelo H., Plantey S., Kotbagi G. Early substance consumption and problematic use of video games in adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:501. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Common Sense Media Social media, social life report (2012): How teens view their digital lives. 2012. http://vjrconsulting.com/storage/socialmediasociallife-final-061812.pdf online. Retrieved from.

- DeCamp W. Who plays violent video games? An exploratory analysis of predictors of playing violent games. Personality and Individual Differences. 2017;117:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L., Coffey C., Carlin J.B., Swift W., Moore E., Patton G.C. Outcomes of occasional cannabis use in adolescence: 10-year follow-up study in Victoria, Australia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;196(04):290–295. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.056952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L., Hall W., Lynskey M. Exploring the association between cannabis use and depression. Addiction. 2003;98(11):1493–1504. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue J.B., Southwell B.G., Betzner A.E., Walsh B.M. Encoded exposure to tobacco use in social media predicts subsequent smoking behavior. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2015;29(4):259–261. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130214-ARB-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico E.J., Miles J.N.V., Tucker J.S. Gateway to curiosity: Medical marijuana ads and intention and use during middle school. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2015;29(3):613–619. doi: 10.1037/adb0000094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw V.A., Elliott M.N., Reisner S.L., Mrug S., Windle M., Emery S.T. Peer victimization, depressive symptoms, and substance use: A longitudinal analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6):e20163426. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elton-Marshall T., Leatherdale S.T., Burkhalter R. Tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug use among aboriginal youth living off-reserve: Results from the youth smoking survey. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2011;183(8):E480–E486. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gommans R., Stevens G.W.J.M., Finne E., Cillessen A.H.N., Boniel-Nissim M., ter Bogt T.F.M. Frequent electronic media communication with friends is associated with higher adolescent substance use. International Journal of Public Health. 2015;60(2):167–177. doi: 10.1007/s00038-014-0624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A. Substance use and common child mental health problems: Examining longitudinal associations in a British sample. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1484–1496. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada . 2016. A framework for the legalization and regulation of cannabis in Canada: The final report of the Task Force on cannabis legalization and regulation. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada Don't drive high. 2018. https://www.canada.ca/en/campaign/don-t-drive-high.html Retrieved May 25, 2018, from.

- Government of Canada (n.d.) Canadian tobacco alcohol and drugs (CTADS): 2015 summary - Canada.ca. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2015-summary.html Retrieved from.

- Gruzd A., Jacobson J., Mai P., Dubois E. 2018. The state of social media in Canada 2017, (february) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel R., Sargent J.D., Poelen E.A.P., Scholte R., Florek E., Sweeting H. Alcohol consumption in movies and adolescent binge drinking in 6 European countries. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):709–720. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada Canadian alcohol and drug use monitoring survey. 2012. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/drug-prevention-treatment/drug-alcohol-use-statistics/canadian-alcohol-drug-use-monitoring-survey-tables-2011.html Retrieved May 28, 2018, from.

- Huang G.C., Unger J.B., Soto D., Fujimoto K., Pentz M.A., Jordan-Marsh M. Peer influences: The impact of online and offline friendship networks on adolescent smoking and alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;54(5):508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss M.J., Sowles S.J., Stelzer-Monahan H.E., Bierut T., Cavazos-Rehg P.A. “It takes longer, but when it hits you it hits you!”: Videos about marijuana edibles on YouTube. Substance Use & Misuse. 2017;52(6):709–716. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1253749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherdale S.T., Ahmed R. Vol. 31. 2011. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/health-promotion-chronic-disease-prevention-canada-research-policy-practice/vol-31-no-4-2011/screen-based-sedentary-behaviours-among-nationally-representative-sample-youth-are-canadian-k (Screen-based sedentary behaviours among a nationally repre-sentative sample of youth: Are Canadian kids couch potatoes?). Retrieved from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherdale S.T., Brown K.S., Carson V., Childs R.A., Dubin J.A., Elliott S.J. The COMPASS study: A longitudinal hierarchical research platform for evaluating natural experiments related to changes in school-level programs, policies and built environment resources. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:331. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherdale S.T., Laxer R.E., Faulkner G. Vol. 2. 2014. www.compass.uwaterloo.ca (Reliability and validity of the physical activity and sedentary behaviour measures in the COMPASS study. Compass Technical Report Series). Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Lissak G. Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: Literature review and case study. Environmental Research. 2018;164:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovato C., Watts A., Stead L.F. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;10:CD003439. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003439.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie C.J., O'Leary-Barrett M., Al-Khudhairy N., Castellanos-Ryan N., Struve M., Topper L. Adolescent bullying, cannabis use and emerging psychotic experiences: A longitudinal general population study. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43(05):1033–1044. doi: 10.1017/S003329171200205X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniglio R. Association between peer victimization in adolescence and cannabis use: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2015;25:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2015.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maras D., Flament M.F., Murray M., Buchholz A., Henderson K.A., Obeid N. Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth. Preventive Medicine. 2015;73:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier M.H., Hill M.L., Small P.J., Luthar S.S. Associations of adolescent cannabis use with academic performance and mental health: A longitudinal study of upper middle class youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;156:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menghrajani P., Klaue K., Dubois-Arber F., Michaud P.-A. Swiss adolescents' and adults' perceptions of cannabis use: A qualitative study. Health Education Research. 2005;20(4):476–484. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minges K.E., Owen N., Salmon J., Chao A., Dunstan D.W., Whittemore R. Reducing youth screen time: Qualitative metasynthesis of findings on barriers and facilitators. Health Psychology. 2015;34(4):381–397. doi: 10.1037/hea0000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishna F., Khoury-Kassabri M., Gadalla T., Daciuk J. Risk factors for involvement in cyber bullying: Victims, bullies and bully–victims. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.08.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M.A., Briner L.R., Williams A., Brockman L., Walker L., Christakis D.A. A content analysis of displayed alcohol references on a social networking web site. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47(2):168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan E.M., Snelson C., Elison-Bowers P. Image and video disclosure of substance use on social media websites. Computers in Human Behavior. 2010;26(6):1405–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern M., Sargent J.D., Engels R.C.M.E., Scholte R.H.J., Florek E., Hunt K. Smoking in movies and adolescent smoking initiation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44(4):339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesi J., Rothenberg W.A., Hussong A.M., Jackson K.M. Friends' alcohol-related social networking site activity predicts escalations in adolescent drinking: Mediation by peer norms. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2017;60(6):641–647. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez-Smith M., Wolf E., Huang H.M., Chen P.G., Lee L., Emanuel E.J. Media exposure and tobacco, illicit drugs, and alcohol use among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Substance Abuse. 2010;31(3):174–192. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2010.495648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas N.L., Sherrit L., Harris S., Knight J.R. The role of parental consent in adolescent substance use research. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42(2):192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rooij A.J., Kuss D.J., Griffiths M.D., Shorter G.W., Schoenmakers T.M., van de Mheen D. The (co-)occurrence of problematic video gaming, substance use, and psychosocial problems in adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2014;3(3):157–165. doi: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ S.A., Larson K., Franke T.M., Halfon N. Associations between media use and health in US children. Academic Pediatrics. 2009;9(5):300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spechler P.A., Allgaier N., Chaarani B., Whelan R., Watts R., Orr C. The initiation of cannabis use in adolescence is predicted by sex-specific psychosocial and neurobiological features. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2018 doi: 10.1111/ejn.13989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada A portrait of Canadian youth. 2018. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-631-x/11-631-x2018001-eng.pdf Retrieved from.

- Statistics Canada Cannabis statistics hub: Cannabis use by sex, lifetime — 2015. 2018. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/13-610-x/cannabis-eng.htm Retrieved from.

- Stern S., Morr L. Portrayals of teen smoking, drinking, and drug use in recent popular movies. Journal of Health Communication. 2013;18(2):179–191. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.688251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiby A.I., Hickman M., Munafò M.R., Heron J., Yip V.L., Macleod J. Adolescent cannabis and tobacco use and educational outcomes at age 16: Birth cohort study. Addiction. 2015;110(4):658–668. doi: 10.1111/add.12827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Haile A., Bredin C., Leatherdale S.T. Vol. 1. 2013. https://uwaterloo.ca/compass-system/publications/rationale-using-active-information-passive-consent (Rationale for using active-information passive-consent permission protocol in COMPASS. Compass Technical Report Series). Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K., Merrin G.J., Ames M.E., Leadbeater B. Marijuana trajectories in Canadian youth: Associations with substance use and mental health. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement. 2018;50(1):17–28. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L., Rivara F.P., Whitehill J.M. Prevalence of marijuana-related traffic on twitter, 2012–2013: A content analysis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2015;18(6):311–319. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh L., Wong B., Faulkner G.E. The independent and interactive associations of screen time and physical activity on mental health, school connectedness and academic achievement among a population-based sample of youth. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry = Journal de l’Academie Canadienne de Psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent. 2015;24(1):17–24. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26336376 Retrieved from. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF Office of Research . United Nations; 2013. Child well-being in rich countries. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White J., Walton D., Walker N. Exploring comorbid use of marijuana, tobacco, and alcohol among 14 to 15-year-olds: Findings from a national survey on adolescent substance use. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):233. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1585-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J., Walton D., Walker N. Exploring comorbid use of marijuana, tobacco, and alcohol among 14 to 15-year-olds: Findings from a national survey on adolescent substance use. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):233. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1585-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study: International Report from the 2013/2014 survey. 2016. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/303438/HSBC-No.7-Growing-up-unequal-Full-Report.pdf?ua=1 Retrieved from.