Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to conduct a qualitative evaluation of a behavioral intervention to prevent and treat childhood obesity in minority children. Using qualitative methods to augment understanding of intervention success may be one way to gain insight into the types of behavior change strategies that are most effective in childhood obesity interventions.

Methods

COACH was a randomized controlled trial of 117 Latino parent-child (ages 3–5) pairs in Nashville, TN that resulted in improved child BMI in intervention vs. control families at 1-year follow-up. All participant parents were invited to focus groups after the trial. Discussions were audiotaped, transcribed, and translated into English. A hierarchical coding scheme was generated, and qualitative analysis done using an inductive/deductive approach. Both theme saturation and consensus between the coders were achieved. Responses were compared between intervention and control groups.

Results

We conducted seven focus groups with 43 participants. 4 themes emerged from the intervention group: 1) perceived barriers to health behavior change; 2) strategies learned to overcome perceived barriers; 3) behavioral changes made in response to the program; and 4) knowledge, skills, and agency for family health behaviors. 4 themes emerged from the control group: 1) a desire to engage in health behaviors without specific strategies; 2) common set of barriers to health behavior change; 3) engagement in literacy activities, including creative problem-solving strategies; and 4) changes made in response to study visits. Analysis of coded data showed the intervention increased healthy behaviors (e.g., fruit/vegetable consumption) despite barriers (e.g., time, cost, culture, family dynamics). Intervention participants described using specific behavior change strategies promoted by the intervention including: substituting ingredients in culturally-normative recipes; avoiding grocery shopping when hungry; and coping with inability to meet goals with acceptance and problem-solving. Control participants reported little success in achieving healthy changes for their family. Intervention participants described successful health behavior changes that were shared across generations and were maintained after the program. Intervention participants reported increased awareness of their own agency in promoting their health.

Conclusions

Qualitative evaluation of COACH provides a more detailed understanding of the intervention's quantitative effectiveness: child and adult health behaviors and personal agency were improved.

Keywords: Childhood obesity, Behavioral interventions, Latino families, Qualitative research

1. Background

Understanding the impact of behavioral interventions for childhood obesity is a complex process as interventions often target multiple levels of a child's social ecology, including individual child behaviors, the family context, and the community infrastructure [1,2]. In addition, the more than 300 behavioral interventions for childhood obesity treatment and prevention evaluated in the last decade have typically yielded small and inconsistent effect sizes for weight change [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]. This is especially true for Latino children, for whom interventions have often failed to reduce the persistent health disparity in childhood obesity prevalence [11]. Such results suggest a significant amount of treatment heterogeneity may not be accounted for by traditional quantitative evaluation methods.

Using qualitative methods to augment understanding of intervention success may be one way to gain insight into the types of behavior change strategies that are most effective in childhood obesity interventions [12]. This is especially true for underserved minority populations, who have a disproportionate prevalence of obesity, who experience significant structural barriers (e.g., poverty, lack of access to healthy foods), and who have cultural perspectives that may impact intervention effectiveness [13]. Qualitative studies investigating intervention successes have predominantly focused on persistent likes or dislikes of families participating in interventions [6]. Consistently reported barriers to participation include time, cost, lack of support from other family members, and challenging physical environments [[14], [15], [16], [17], [18]]. In addition, qualitative data suggest that interventions are most successful when they facilitate new skillsets to overcome barriers, including strategies for establishing healthy eating patterns, improving parent-child interactions, and increasing physical activity [14]. Consequently, the use of a qualitative evaluation methods in obesity interventions is an important component of understanding the effectiveness or lack thereof for an intervention. However, current qualitative data are sparse for families with small children in underserved communities, and additional qualitative investigations have the potential to better define the strengths and weaknesses of family-centered behavioral interventions, what helps a family make long-term changes, and how to use that information to tailor interventions for each family's or community's needs.

The purpose of this study was to conduct a qualitative evaluation of a family-centered childhood obesity intervention, with the goal of expanding the traditional quantitative metrics of intervention effectiveness. Competency Based Approaches to Community Health (COACH) is a personalized behavioral intervention to prevent and treat childhood obesity among 3-5 year-old Hispanic/Latino children. In a recently completed randomized controlled trial of 117 Latino parent-child pairs, the COACH intervention achieved the primary outcome of reducing linear BMI growth in intervention participants compared to control participants [19]. By conducting focus groups among the parents of children who participated in both the intervention and control groups, we aimed to understand their perceptions of the following: 1) what changes in healthy behavior did families make in response to the intervention; 2) what were common barriers to healthy behavior change and what strategies did families learn to overcome those barriers; and 3) what components of the intervention were most effective in facilitating adoption of new behavior change strategies. While some of these constructs were assessed by quantitative survey results in the original study, the use of qualitative methods allows for a fuller evaluation of specific types of behavior change, and the way that those health behaviors may have interacted with specific facilitators and barriers.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

We conducted seven focus groups with parents of participating children in the COACH trial who were initially recruited at local community centers, physician waiting rooms, and other community locations like grocery stores [20]. Each focus group was conducted by a native Spanish-speaker. The focus groups were conducted by the same individual, who is a certified health coach, and who had not had exposure to the participants during the study. Focus groups were conducted in local community centers and generally lasted 60 min. All participants from the study were invited to participate in one of the focus groups 9 months after the baseline data collection (3 months after completing intervention content). Participants were invited to focus groups using multiple approaches including text messages, phone calls from the study team, and in-person invitations at study sessions. Several reminders were sent to each participant. Participants from both the intervention and control arms of the study were invited to participate, though separate groups were conducted for each arm. The purpose of inviting both intervention and control group participants was to compare the key themes between groups to 1) gauge the potential impact of the intervention and 2) evaluate the perceived value of the control group. Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card for their participation in the focus group session.

The full methods of COACH have been previously reported [21]. The intervention lasted 6-months, consisting of two phases: an intensive phase consisting of 15 weekly group sessions conducted in local community centers by a health coach, followed by a maintenance phase, where participants received two health coaching calls per month for three months. The content of the intervention was culturally tailored (e.g., using culturally normative recipes, addressing barriers unique to Latino immigrants, etc.) and delivered in Spanish by a natively bilingual health coach. At each in-person sessions, children and parents received intervention content separately, then returned together for a shared meal and shared application activity that focused on the content taught during the session. The intervention delivered a personalized curriculum focusing on 7 key health behaviors including 1) fruits/vegetables 2) snacks 3) sugary drinks, 4) healthy physical activity, 5) healthy sleep, 6) healthy media use, and 7) engaged parenting. The intervention focused on building competencies in these health behaviors, incorporating goal setting, shared problem solving, and self-monitoring. Control group participants received a school-readiness curriculum, also delivered in community centers by the same health coach.

All participants signed an informed consent document prior to study participation. The Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study.

2.2. Data collection

Discussion questions were designed to elicit participant's responses to the following key questions:

-

1)

COACH was designed to help you make changes for the health of your family. Thinking about your family now, compared to before the program, what changes did you make for your family because of COACH?

-

2)

Were there areas of your life that you wanted to change that you didn't? What made it hard to change those areas?

-

3)

What things did we do during the COACH sessions that helped you the most to make changes for your family's health?

Questions were designed as open-ended, and a moderator guide provided specific follow-up prompts to solicit additional detail (Appendix A). As a part of the original study data collection, parent-reported demographics were obtained.

2.3. Data analysis

Focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed in Spanish. They were translated into English by two independent members of the study team who are natively bilingual and checked for accuracy. Quotes were coded in English, then back-translated to Spanish to ensure appropriate interpretation. Prior to analysis, the transcriptions were verified and de-identified. To evaluate whether the sample size was sufficient, transcripts were read in their entirety to evaluate for thematic saturation, defined when no additional higher-level themes emerged after coding additional focus groups [22]. A hierarchical coding structure was developed using an iterative inductive-deductive approach based on the moderator guide and focus group transcripts [23]. Definitions and rules were written for the use of each category (Appendix B). Two experienced qualitative coders first established reliability in using the coding system, then independently coded each of the transcripts groups with differences resolved by consensus. Each statement was treated as a separate quote and could be assigned up to five different codes. Analysis consisted of interpreting the coded quotes and identifying higher-order themes, using an iterative inductive-deductive approach. Data were analyzed separately for intervention and control group participants, though the same coding scheme was used. Management of transcripts, quotations, and codes used Microsoft Excel 2016 and SPSS version 25.0.

3. Results

3.1. Participant demographics

Of the 117 participants enrolled in the original RCT, 43 (18 intervention, 18 control, 7 family members of index participants) participated in a focus group following the intervention. The average age of focus group participants was 33.8 (5.6) years, 98% were women, 19% were employed full time, and 33% reported an annual household income of <$20,000. There were no substantive differences between demographics of the 43 focus group participants and the original 117 participants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics.

| Original Randomized Sample (N = 117) | Focus Group Participants (N = 43) | |

|---|---|---|

| Parent Characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | 32.5 (6.0) | 33.8 (5.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.0 (6.2) | 30.7 (5.1) |

| Education | ||

| 8th grade or less | 27 (23.1%) | 13 (30.2%) |

| Some high school | 30 (25.6%) | 7 (16.2%) |

| High school graduate or GED | 44 (37.6%) | 17 (39.5%) |

| Some college or more | 16 (13.7%) | 6 (13.9%) |

3.2. Conceptual model

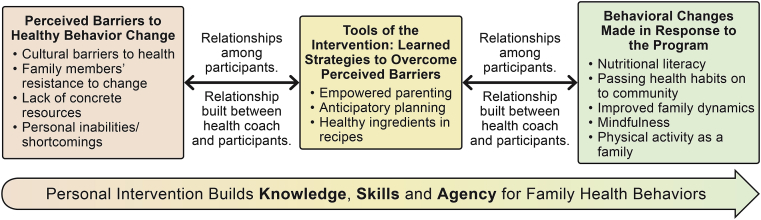

Using the inductive-deductive approach, we identified 5 key themes: 1) knowledge, skills, and agency for family healthy behaviors; 2) perceived barriers to healthy behavior change; 3) tools of the intervention: learned strategies to overcome perceived barriers; 4) behavioral changes made in response to the program; and 5) relationships built during the program. We then developed a conceptual model illustrating how these key themes relate to one another (Fig. 1). The conceptual model highlights how perceived barriers to healthy behavior change were associated with learned strategies to overcome perceived barriers, and how those learned strategies were associated with behavioral changes made in response to the program. Relationships built during the program (both among participants and between participants and the health coach) were reported by participants as factors essential for both accessing intervention content and for the application of those tools to facilitative behavior change.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual Model.

3.3. Theme 1: perceived barriers to health behavior change

The primary barriers identified by the intervention group participants included cultural barriers, family dynamics, lack of concrete resources, and personal inabilities/shortcomings (Table 2). Cultural barriers were attributed to acculturation as well as norms in country of origin. For example, some participants identified that since coming to the United States they were less active/more sedentary with greater access to fast food and more restricted access to fresh foods. Participants also reported cooking with less healthy ingredients in recipes from native countries. In addition, participants repeatedly identified a sense of isolation since moving to the United States, as they were far from their support networks. Because of this, one of the main perceived advantages of the intervention was the relationships built both among participants and between participants and the health coach. These relationships facilitated health behavior change, but also spilled over into other areas of life, with participants reporting more frequent use of other community resources because of a stronger sense of connectedness to other members of their community.

Table 2.

Representative quotations from intervention group participants relating to Perceived Barriers to Health Behavior Change.

| Theme 1a. Cultural barriers to health |

| The issue is with me personally; the bad habits I have been dealing with forever. I think that since I got to this country, it's been like that, because I turned into a sedentary person when I came here. In Mexico I practiced sports, I was always active, walking. I got here and started using the car, no activity, winter months are sedentary and we eat a lot, I gained weight. (Session 7, Participant #43) |

| Theme 1b. Family members' resistance to change |

| I mean, he's [husband] not a child, and I tell him all the time, “You can do it, go ahead.” So it's just with meals, I cook so he has to eat my food. And when he doesn't want to, he says, “No, not this food. You just make boiled vegetables.” And then he'll cook for himself. So I haven't been able to achieve that challenge because he cooks whatever he wants for himself. (Session 4, Participant # 26) |

| The most difficult change has been – I think there have been two for me. One was the television and the tablet. That was the hardest thing for me to take away from them. Why? Because they would spend practically from the time they got home from school until it got dark watching the tablet or television. And when – I found it hard to take it away from them, because when they are focused on the television, they do not pay attention to you. So, that is why I found it so hard to take it away from them. (Session 1, Participant #6) |

| Theme 1c. Lack of concrete resources (built environment, time, money) |

| With exercise? The thing is that sometimes … I have to get my work done so that I can make deliveries and I am unable to take care of my kids. That is what affects me regarding my time and them exercising more while I am watching them to make sure they do not get hurt or things like that. (Session 1, Participant #6) |

| Because sometimes when I wanted to go out for a walk, there was a lot of traffic. I lived in an area that – I live in an area that has a lot of traffic. So, for me, that is – that is like an obstacle to – to do it every day. There are days when the traffic is very heavy and there are days when it is not. Therefore, for me, that was an obstacle, getting them out to take a walk on a day that I had planned to do that previously … (Session 1, Participant #2) |

| Theme 1d. Personal inabilities/shortcomings |

| Sometimes I was too lazy to go out and walk. I mean, I do go out with the girls sometimes so they can play at the park, but they play and I sit. Sometimes I would walk, but no, I think that's what has been the most difficult. I've even gone to the doctor and he tells me, “You have to walk for 30 min in the morning and 30 min in the afternoon.” I don't do it. I'll walk 10 min and my tongue will be hanging out, but I think you have to get into the habit. If you don't, then it won't happen and that's what has been the most difficult thing for me; going out to walk. (Session 5, Participant #35) |

Family dynamics was identified as another major barrier to health behavior change. The major issues raised by participants were children's resistance to limits on screen time, a clearly set bed time, and increased fruit/vegetable intake. However, parents noted resisting giving in to children's complaints despite the toll/struggle because healthier eating is ultimately worth it and for their children's good. Other adult family members modeling unhealthy behaviors (e.g., high screen time, sedentary activities) or even encouraging unhealthy choices (e.g., providing kids with unhealthy foods) was identified as another family dynamic issue. For intervention participants, built environment was a barrier because of safety concerns, limited access to public indoor and outdoor spaces, and climate. Finally, intervention participants noted internal barriers to making their own behavioral changes or breaking unhealthy habits especially with regards to physical activity. For example, some participants identified an internal lack of motivation—“laziness”—while others identified long-standing unhealthy behaviors in their own lives as barriers to family behavior change.

3.4. Theme 2. tools of the intervention: strategies learned to overcome perceived barriers

Intervention participants described specific behavioral strategies learned during the intervention to overcome perceived barriers to health behavior change: 1) empowered and creative parenting to overcome family members’ resistance to change; 2) anticipatory planning to overcome a lack of concrete resources, and 3) incorporating healthy ingredients into typical recipes to overcome cultural barriers (Table 3). Participants reported using creative and learned strategies to get their children/families to consume healthy foods. The most often cited way of overcoming lack of concrete resources for physical activity was coming up with ways to be physically active inside their own homes. Very specific behavior change strategies were mentioned: ingredient substitution in culturally-normative recipes, not grocery shopping when hungry, extending judgement-free self-acceptance when circumstances are prohibitive but still pursuing the goal even when not fully attained.

Table 3.

Representative quotations from intervention participants describing Learned Strategies to Overcome Barriers to Health Behavior Change.

| Theme 2a. Empowered and creative parenting to overcome family members' resistance to change |

| At my house there were no – you could not find any vegetables before, but now you can. What I have done for them to eat vegetables is that, for example, I'll cook squash filled with meat and cheese and I put colorful vegetables in it, which gets them interested and they want to taste it. And that has worked for me … We didn't know about those things before. (Session 1, Participant #6) |

| Because I think that natural water is healthier than flavored water with so much sugar. So, just like her, I used to give to my children juice and I still do, the reduced juice … I make half of it water, half of it juice … They drink it as if nothing has changed. (Session 1, Participant #5) |

| For me, the hardest one has been the one about the phone and the television. Because the kids always want to keep watching and I have to speak strongly to them to obey because they do not want to. They become like addicted and that's why it is so hard … [You have to] turn it off even if they cry. To make the decision oneself, because they are not going to want to. Take them outside. Like, "Let's go to the park." Doing another activity that they like. (Session 1, Participant #3) |

| Theme 2b. Anticipatory planning to overcome lack of concrete resources |

| I think that for me, what has been a bit difficult is taking them out for walks when the weather is cold. You know that the temperature is cold outside, but I think that inside the house I can do some other type of activity. Like take them out – I mean, or – or have them do something in the house where they are moving their bodies, so they are not just sitting down. (Session 1, Participant #2) |

| Because they also ask for [fruits and vegetables], because I went to drop off one of my daughters and then I came back and I didn't have time to go back home, so I carry something healthy in case they get hungry and ask me for something. (Session 7, Participant #43) |

| Theme 2c. Incorporating healthy ingredients into typical recipes to overcome cultural barriers |

| I'm from El Salvador. We cook differently than they do here. We would make—so, for instance, to make scrambled eggs, we would add tomatoes, onions, oil, and lots of it. Now I might make scrambled eggs, but I won't make it the same way. We've changed the brand of oil that we use, I mean, we look at the amount of cholesterol that it has, the fat—in what we are going to eat. (Session 4, Participant #25) |

Six sub-themes emerged around intervention participants' perceived value/effectiveness of the intervention content, including: 1) general positive feelings about the program; 2) a perceived linkage between program content to changed behaviors; 3) social support from fellow intervention participants as essential for behavior change; 4) goal setting and accountability as helpful in behavior change; 5) interpersonal connectedness to the health coach; and 6) personalized health coaching calls as less effective than in person sessions (Table 4). In response to general questions about the program's effectiveness, intervention participants reported an eagerness for the program to continue, and mentioned their children were eager to participate too. Intervention participants appreciated that both themselves and their children learned about nutritional literacy and were exposed to healthier food options.

Table 4.

Representative quotations from intervention group participants regarding perceived value and effectiveness of intervention content.

| Theme 4a. General positive feelings about the program |

| I would like to thank those who developed this program, especially those who invited us and those who taught us, all of them, because I imagine we were a large group, so we met a few people, but there were many people who thought about us or saw the need to change us, especially us Hispanics because most of us suffer from obesity here. (Session 7, Participant #43) |

| Theme 4b. Increased healthy food and health literacy as a result of COACH sessions |

| They were taught about fruits, about vegetables. They were taught about all the amounts of sugar in drinks and since they're young—I have an eight-year-old and a three-year-old and she says, “Oh,” and when they stop listening to it, they start to forget. My daughter reads labels. "Oh, mom, this contains a lot of sugar." (Session 7, Participant #41) |

| Another thing is also that they taught children. It also helped my daughter a lot to learn about what drinks contain and they also talked about fruits and vegetables. That makes an impact in children when they are young, the way they teach it and explain it to them and that it's not mom or dad or siblings that's telling them, so they learn and when they get home, they say, “No, mom, no juice, because juice contains a lot of sugar and that's very harmful for teeth and it hurts you.” So, it's important, it's very important. It was important to my daughter and also for me, because it helped me. It helped me learn that with her. For me, that's the good thing. (Session 7, Participant #43) |

| Theme 4c. Social support was crucial to achieving goals |

| I remember that at first, I was scared, I didn't think was I was going to be able to do it. But that changed when we would achieve the goals we had as a group. Coming each week and having them ask you, “Did you achieve your goal?” Or “Did you get the call?” (Session 4, Participant #31) |

| I prefer in person more because it motivates you more to accomplish your goal or to set goals. And we all share our own opinions or we gave each other advice, to one another. And we help each other out with a problem we may be having with one of our children. (Session 1, Participant #8) |

| It motivated me, because I've always tried to make changes in my life with regard to the way I eat, my weight, to change my weight, because I know I'm overweight, but I would always achieve a goal and then, I would gain weight again. It's not something that would become a habit in my life, losing weight and keeping it off, so this group offered all those things that were going to help me, that were helping me and we actually started off really good … when you face obstacles you need a friend … I have my husband and my children, but we always need someone else to lean on and yes, the group was always an important part of this change … (Session 7, Participant #43) |

| Theme 4d. Goal setting and accountability were extremely useful |

| Well, I would say that something that helped us, for example, was that there was a goal we had to meet each week. That gave us a sense of accountability, as we say in Spanish - and it made you feel a little more responsible to apply at home what you learned in class in order to bring the results the following week. (Session 5, Participant #34) |

| What helped me was when they taught us about setting goals and then in turn trying to achieve them. So, that is what stood out to me, and I learned that here, to each week set our goals and we would try to achieve them. That helped me a lot. (Session 1, Participant #8) |

| Theme 4e. Fondness for interventionist |

| What I liked about her is that she is someone that motivates you. Why? Because she is always happy. The times that I came, I never saw her be rude or – or be upset or anything. I think that we all have problems, you know, but she really knew how to separate one thing from the other. So, she always talked to you and made you feel good. She has this I do not know what that – that makes you feel good. She is a person with an angel. (Session 1, Participant #6). |

| I felt comfortable with [interventionist]. She motivates you and helps you, encourages you, and well, she with us in her struggles because she also lives with that struggle. (Session 7, Participant #43) |

| Theme 4f. Coaching calls |

| Having her call was one more motivation for us, because we knew we had like that push and we had to do things because she was going to call us to ask. On the other hand, if she would have stopped calling, and we wouldn't have done it until now, well, I think we would have gone back to our old ways and we would have gone back to the poor nutrition or maybe also eating healthy, but not the same, so having her call would also motivate us to do things, because she was going to call to ask how we did. (Session 5, Participant #35) |

| And they do help, but it is not the same as coming here and being with the group … Because – the difference is that on the phone, you are only talking to the person calling and in the group, we can come and all share our experiences. That is the difference. (Session 1, Participant #2) |

| I only received one and to be honest, I got really nervous. I do not know why, but I felt like I was not going to be able to answer the questions properly. Like my friend said, it is also much better in my opinion to come here, because you are able to interact with everyone else. And on the phone, yes, you are talking to someone else, but you do not see their face. So, it is more complicated, for me, in my opinion. I would feel more comfortable talking to the person face-to-face. (Session 1, Participant #6) |

The most frequent comment with regards to intervention program feedback was how critical the social component of the program was to successfully achieve health related behavior goals, for accountability but more for empathetic supporter. Similarly, there were numerous positive comments about the health coach – her personal demeanor, comradery and availability. They also saw the goal setting process as critical, noting the positive motivation to attain goals instead of fear of failure. Participants reported that the supportive and trusting relationships with each other and with their health coach supported them in accessing and applying the intervention content. These relationships helped participants understand intervention content in new ways, and it made them feel more confident to try new things.

While one participant said phone calls were an effective means of accountability for continuing to pursue goals, most felt anxious about them and preferred talking with the whole group about their goals instead of one person, even if that person was the interventionist who they trusted. In addition to requesting reduction/elimination of phone calls, the intervention group also requested stricter/more valid check-ins to verify that goals were being met.

3.5. Theme 3. behavioral changes made in response to the program

Intervention group participants identified 6 major areas of behavior change in response to the intervention. These included: 1) improved nutritional literacy and introduction of healthy foods; 2) passing on healthy habits to the children and community, with the future in mind; 3) engaged parenting and improved family dynamics; 4) mindfulness and holistic well-being; 5) physical activity as a family; and 6) limited screen time (Table 5). The major emerging theme was families wanted to pass on lessons learned about healthy eating to their children, extended family and friends because they recognized the long-term health risks (obesity, diabetes, high cholesterol) and want to prevent them.

Table 5.

Representative quotations from intervention participants regarding behavioral changes made in response to the program.

| Theme 5a. Nutritional literacy and introduction of healthy foods |

| The changes made in my home were radical because in my house not a single day passed without us drinking soda. Every day, there was soda. In the morning, there was soda, with lunch, and even at dinner. So, during the time I have been coming here, I have learned that soda is terrible. It is terrible and so I cut it out. They no longer drink soda. (Session 1, Participant #6) |

| We see changes … when you open up the fridge, you don't have what you used to have; junk food or things that weren't even nutritious or helpful unless it was for weight gain and that's not the case anymore. Now, we've learned a lot of things. Now, we even check what it contains in the back. My daughters check. (Session 5, Participant #35) |

| I wouldn't drink water and now, I drink more water. I eat healthy. My children eat more vegetables. I learned how to make soup and use the blended vegetables. I give them to my children and we drink more water. (Session 5, Participant #39) |

| Theme 5b. Passing on healthy habits to children/community, with the future in mind |

| If you take them [to fast food places] constantly, that's your inheritance to them and then, when you want to make changes, it's not possible. When they get to a certain age when it's very difficult to make them change, they won't understand it until they're older and see the consequences this brings on, once they're sick, when they want to go back in time to say, "I shouldn't have--if I would have exercised, if I would have eaten healthier … " But, there's no going back in time. This needs to happen now and that way, they learn to eat healthier and say, “I can't eat that all the time.” (Session 5, Participant #35) |

| I have a sister in Puerto Rico. She's fourteen years old … She is obese and her doctor has told her that if she doesn't lose 16 lbs. she's going to have to get insulin injections and since I started the program … each time I would come here, I would pass on the recipes to her. “Cook soup like this,” or “Make rice this way,” “Eat this or that.” I would tell her about the class … now she's looking for the recipes because I would send her the pictures of the meals you cooked and she's eating more fruit and eating—she calls me to get ideas about what you would teach here in class and she has lost 8 lbs. (Session 5, Participant #38) |

| With my neighbor, she would see that I would do challenges each day, so she would ask me about—she would ask me, "Where are you going?" I would tell her that I had goals and that I had to meet them, so she asked me what they were about, and I explained it to her. So I told her about the program and that--well, her children are grown up, so she wanted to follow my footsteps. I taught her about they were teaching us here and she followed it. (Session 5, Participant #39) |

| Theme 5c. Engaged parenting and improved family dynamics |

| And to share more time as a family. At the mealtime I turn off the television, stop talking on the phone so that we can spend more time together, how was school, how was work. And that is thanks to the program, because before we had the TV on, the tablet on one side, phone talking on the other, eating we did not talk. We did not spend time together as a family. And the thing is that thanks to this we learned this: it is good to share as a family and not have the TV on. (Session 1, Participant #8) |

| They would say, "Oh, if you don't let me watch TV, I'm not going to eat." That is what they would tell me. So, little by little, I started showing them that the television and tablet aren't – aren't very good for – how can I explain this, like, for them – for them to concentrate, because when they're on the tablet, they don't eat and their bodies aren't strong, their minds are wandering. And so that was hard. But now they have understood a bit more that they need to spend time with their siblings and not with a screen. (Session 1, Participant #6) |

| Theme 5d. Mindfulness and holistic well-being |

| When I gave birth to my baby, one way I found take care of one child and the other and my two other older daughters and do housework was easily giving my daughter an ipad. So I realized the harm I was doing to her by being in front of an electronic device for so long, so I did eliminate that drastically. I don't know if it's very harmful, but I took it away from her and I think it has helped her more, because now, she grabs coloring books and she's more interested in writing and coloring and doing other activities than in being on the tablet. (Session 7, Participant #42) |

| Yes, for me it's walking. I walk every day. To be honest, the body asks for it. Last week, I got up late and I wouldn't come, but in the afternoon, I would think, “I have to walk. I need to walk or go out and play or something. (Session 7, Participant #41) |

| Theme 5e. Physical activity as a family |

| And with exercise, I have also improved with that, because I used to be very sedentary. I hardly ever went out for walks. I was always sitting and watching television and I am not like that anymore. That has really helped me a lot because since I am sick, I need – my body needs that exercise. And my family does not leave me alone, so they come out with me and – and we all enjoy the evenings together as a family. And we spend more time together as well. (Session 1, Participant #6) |

| For example, I did not do a lot of activity at home, so it was like, oh, I am tired, it is a routine. So, that helped me to set goals for myself and – and in turn my daughters would say, Mommy, we can do it. We are going all to go do it and say we achieved it. So, that helped me, motivated me practically. To try to at least get out of the house to go walking. (Session 1, Participant #8) |

3.6. Theme 4: knowledge, skills, and agency for family health behaviors

Intervention participants reported building knowledge and skills for healthy behaviors throughout the study. In addition, it became clear that their own personal health schemas were changing, such that they recognized themselves as agents for change in their own health and the health of their family (Table 6). No longer did health happen to them, but they had the capacity to affect change for their families. Participants recognized the importance of building knowledge and skills in key parenting areas as well as developing strategies to overcome barriers to health behavior change. Through this process, the participants reported seeing their family's health as a process of positive changes over time.

Table 6.

Representative quotations from intervention group participants regarding developing knowledge, skills, and agency for health behaviors.

| Yes, we learned a lot, also going to the grocery store, like [interventionist] said, we shouldn't go when we're hungry, because we'll get all kinds of things, everything we crave. If we're hungry, we put everything we see into the shopping cart and when you eat you think, “Why did I get all of this?” Things you really don't even need, so I learned to go shopping when I was full, so I won't go down the aisles putting in things I don't need. (Session 5, Participant #35) |

| Well, the obstacles have been that my children have gotten sick and I've been sleepless. When you're sleepless, you don't have the same energy as a mother and your mood also changes, because you haven't slept enough. Those are obstacles, so I let the bad times go by, the times with sickness and then the good times come along, so that's when you have to make an effort as a parent to offer them the best, especially because the four-year-old will get sick and the one-year-old will get sick, so it's difficult week after week, two weeks in a row. Two weeks without being able to sleep well, staying up at night. It's difficult, but nothing is impossible. Maybe I won't be at 100% at that moment, but the rest of the time, during what I call the good times, I'll be at 100% which is most of the time in their lives and mine. (Session 7, Participant #43) |

3.7. Control group

Four themes emerged from discussions that included the control group participants, including: 1) a desire to engage in health behaviors without specific strategies; 2) common set of barriers to health behavior change; 3) engagement in literacy activities, including creative problem solving strategies; and 4) changes made in response to study visits (Table 7). Participants from the control group reported a similar set of barriers to healthy behavior change. While it was common for control group participants to identify a desire to enact healthy behavior change in their families, they did not often cite specific strategies for overcoming barriers to health behavior change. Importantly, focus group participants reported that one of the inciting reasons that they started working on health behaviors was because the study team routinely asked them about healthy diet as a part of the study survey. In addition, control group participants reported increased engagement with literacy activities and often described strategies to engage their children in reading and to encourage library use.

Table 7.

Representative quotations from control group participants.

| Theme 7a. Desire to Engage in Health Behaviors |

| I'm very interested in my family's health, because financially, we can't go to the doctor as often, so I'd rather take care of them from the beginning so that we don't struggle, because I live with my husband who currently has health problems. He can no longer eat certain things and I see that my son is starting to eat many of the things that caused my husband's problem, so I don't want him to go down the same path and end up with the same problems. I want him to start eating healthy things. (Session 3, Participant #19) |

| At first, I thought it was really hard but I figured it was a change that was for the better, for the whole family. And if possible, for those who are far from us, we need to let them know that by eating vegetables and cutting out certain things, you can change the way you eat in a healthy manner. Oh, like a friend that we see is doing really bad or – or any other family member who isn't close to us, we can tell them, "Hey, look at this and this, you can do this." That way it can help them with their health and they won't have as many complications. (Session 6, Participant #40) |

| Theme 7b. Common Set of Barriers to Health Behavior Change |

| Another challenge I face is with food, because it's not just at home. I can watch what I cook at home, but my child goes somewhere else, with other friends and other families don't have the same values, so that's a challenge for me. I still haven't overcome that … He'll want to go to McDonald's and I tell him, “I don't go to McDonald's.” “But, they're going to McDonalds!” And he will throw a fit, but I won't go, regardless, but it makes me frustrated because he cries, but I still don't do what he wants, but it kind of pains me that he sees his other friends that their moms allow them things that I don't allow him and most of us Hispanics are kind of like that. (Session 3, Participant #19) |

| We don't have the habit. We come from a culture where—I don't know if it's because of the scarcity we lived. I don't know if it's that, because it could be that. I can't criticize the reason. Maybe it's because it's so easy to get a hold of all those things, so we take everything we can. (Session 3, Participant #19) |

| Theme 7c. Engagement in Literacy Activities, including creative problem solving strategies. |

| Mine is that every night, before going to bed, my daughter always asks me to read her a book, but not from a book. I make a story out of everything they did that day. I create, so that she can imagine, I mean, relive all the moments we experienced throughout the day and she feels very happy and she tells me to go on and on and she doesn't want it to end and it's really nice because I was taught that here. I learned about that imagination with you, that time I came and you started telling us to imagine a lot of things with little pieces of paper that you gave us. So, I got that experience since then and now, I do that every night with my daughter and it's really nice seeing her little face reminding her about everything she did during the day. (Session 3, Participant #17) |

| Well, in the past, my son—well, you know, I was tired when I'd get home from work and he'd say, “Mommy, read this book to me.” And I would say, “Oh, son, just go to sleep instead. I'm really tired,” or “take a bath and, I'll read it to you tomorrow.” But, now he's starting to read and you learn too and you have fun with the child and he goes happy to bed. (Session 3, Participant #19) |

| Well, now I read books to my children. I wouldn't do it before. Now, I read books to them every night. I participate with them more. I play with them and I think they feel closer to me and I think it has been very helpful. (Session 3, Participant #17) |

| I'm the type of person who is very closed-minded and this program has helped me because sometimes I limit myself to—I wouldn't go to the library, because of certain things, but one day I was brave and said, “No! I'm going inside the library because I came to the library,” and I went in and it was like, you need to get yourself up or like this program, ask for information or help from people who know more, but since I'm closed-minded, I limit myself, but thanks to this program, I've gotten braver. (Session 3, Particpiant #19) |

| Theme 7d. Changes made in response to research study visits |

| Well, personally, every time the lady asked me, “How much juice do you give your child a day?” And I would answer, I mean, it was a question that made me think that something was wrong, I shouldn't be doing this. And that's when I started analyzing that all the questions they were asking me were because I was doing something wrong and I started taking that into consideration. (Session 3, Particiant #17) |

| Well, before you guys, I wouldn't feed my children fruits, because they didn't want to eat fruit, so I would take them to McDonald's to eat French fries, junk food. Once you guys got here and started visiting me and started asking me questions like how much fruit my children ate a week and whether we exercised, I realized I wasn't doing any of the things you were asking me, so my goal was that I would buy fruit for my children, I would teach them to eat fruit and that's what I'm doing and I will continue to do so, because it's something healthy for them, to eat a piece of fruit instead of taking them to eat at McDonald's. It's better to cook at home and you've taught me all of that with all the questions you ask me and when I realized I wasn't doing it, I started doing it and my goal is to continue doing it and that's why I'm grateful for this program. (Session 3, Participant #17) |

| Well, through the – the – when they were going to measure or weigh us, my daughter. at home, that's when I noticed that they asked us what we were eating and how often, because I was in the reading one. So, I started to also be more interested in nutrition. And I started cooking more vegetables for us as well, the adults, because out of convenience, I would just cook the quickest thing, which was chicken and rice. And that's it. And the kids do eat that well. (Session 6, Participant # 37) |

4. Discussion

This qualitative analysis of focus groups from the COACH intervention participants reveals that participants consistently reported positive changes in beneficial health behaviors such as health eating, physical activity, improved family dynamics, and general well-being. These findings lend credence to the explanatory behavior change models that link health behavior change to the quantitative reduction in child BMI reported in the original trial. In addition, participants report a broader reach of the health changes made in their lives, including the fact that health behavior changes were spread across generations and to community members who did not participate in COACH. Participants also reported that these positive health behavior changes continued after the COACH intervention ended. In addition, the findings suggest that strengthening connectedness within communities may be a key strategy for improving health, especially in minority populations.

Data from these focus groups advances the field in childhood obesity prevention through providing several key insights into the perceived value of behavior change interventions in low-income, minority communities. First, the importance of relationship building was underscored by participants, both among participants and between participants and the health coach who delivered intervention content. These supportive relationships were seen as a remedy to the social isolation that was so typical in this immigrant community. In addition, participants reported the value of these newly built relationships to both accessing intervention content during sessions and to applying it to their lives.

The inclusion of the control group participants in these focus groups also provides a unique perspective on the effectiveness of the intervention. While control group participants reported that they intended to make changes to their health as a result of the questions asked in the survey (Hawthorne effect), they were unable to identify specific strategies to implement those changes. This highlights that effective behavior change is not just identifying the need or desire to make changes, but also having access to ideational tools (knowledge of health practices), material tools (access to a kitchen and fresh food), and social tools (support/encouragement). This triad of supports sustained behavior changes. In addition, the control group was able to articulate real benefits to their family life, and changes in their literacy-related practices based on the educational content of the control group. This value-added was the likely explanation for the lack of differential attrition reported in the randomized trial, and points to the importance of meaningful control conditions in behavioral interventions.

4.1. Limitations

All intervention participants did not attend a focus group session, which presents the potential for a selection bias. While the baseline demographics of the focus group participants did not differ from the overall study, it is likely that non-responders to the intervention were less likely to participate, biasing the conclusions of this qualitative study. The findings from this study are not generalizable to the general population, but rather indicate the perceived value of the intervention among this low-income minority population. The goal of these focus groups is not to essentialize the Hispanic/Latino experience in the U.S [24]. Rather, the goal is to develop a more nuanced perspective on how Hispanic/Latino families view health behavior change in the context of childhood obesity, with the aim of contextualizing future interventions to support healthy child growth and development.

5. Conclusions

This qualitative evaluation of the COACH intervention provides a more detailed understanding of the intervention's quantitative effectiveness: health behaviors and personal agency were improved by the intervention through social support developed among participants. This should encourage the incorporation of qualitative evaluation methods into behavioral interventions. It also suggests the potential value of personalized, culturally-sensitive approaches for childhood obesity prevention in low-income minority populations.

Funding source

This study was funded by the Department of Pediatrics at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Turner-Hazinski Award. In addition, Dr. Heerman's time was supported by a K23 award from NHLBI (K23 HL127104).

Author disclosure statement

No competing financial interests exist for any of the authors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100452.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Ohri-Vachaspati P., DeLia D., DeWeese R.S., Crespo N.C., Todd M., Yedidia M.J. The relative contribution of layers of the Social Ecological Model to childhood obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(11):2055–2066. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014002365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiraly C., Turk M.T., Kalarchian M.A., Shaffer C. Applying ecological frameworks in obesity intervention studies in hispanic/latino youth:: a systematic review. Hisp. Health Care Int. 2017;15(3):130–142. doi: 10.1177/1540415317731069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heerman W.J., JaKa M.M., Berge J.M., Trapl E.S., Sommer E.C., Samuels L.R., Jackson N., Haapala J.L., Kunin-Batson A.S., Olson-Bullis B.A., Hardin H.K., Sherwood N.E., Barkin S.L. The dose of behavioral interventions to prevent and treat childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-regression. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017;14(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0615-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.JaKa M.M., Haapala J.L., Trapl E.S., Kunin-Batson A.S., Olson-Bullis B.A., Heerman W.J., Berge J.M., Moore S.M., Matheson D., Sherwood N.E. Reporting of treatment fidelity in behavioural paediatric obesity intervention trials: a systematic review. Obes. Rev. : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2016;17(12):1287–1300. doi: 10.1111/obr.12464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waters E., de Silva-Sanigorski A., Hall B.J., Brown T., Campbell K.J., Gao Y., Armstrong R., Prosser L., Summerbell C.D. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011;(12):CD001871. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oude Luttikhuis H., Baur L., Jansen H., Shrewsbury V.A., O'Malley C., Stolk R.P., Summerbell C.D. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009;1:CD001872. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001872.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boon C.S., Clydesdale F.M. A review of childhood and adolescent obesity interventions. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005;45(7–8):511–525. doi: 10.1080/10408690590957160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young K.M., Northern J.J., Lister K.M., Drummond J.A., O'Brien W.H. A meta-analysis of family-behavioral weight-loss treatments for children. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007;27(2):240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seo D.C., Sa J. A meta-analysis of obesity interventions among U.S. minority children. J. Adolesc. Health. 2010;46(4):309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stice E., Shaw H., Marti C.N. A meta-analytic review of obesity prevention programs for children and adolescents: the skinny on interventions that work. Psychol. Bull. 2006;132(5):667–691. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez-Morales M.E., Bacardi-Gascon M., Jimenez-Cruz A. Childhood overweight and obesity prevention interventions among Hispanic children in the United States: systematic review. Nutr. Hosp. 2012;27(5):1415–1421. doi: 10.3305/nh.2012.27.5.5973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teddlie C., Tashakkori A. Sage; 2009. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hargreaves M.K., Schlundt D.G., Buchowski M.S. Contextual factors influencing the eating behaviours of african American women: a focus group investigation. Ethn. Health. 2002;7(3):133–147. doi: 10.1080/1355785022000041980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonneville K.R., La Pelle N., Taveras E.M., Gillman M.W., Prosser L.A. Economic and other barriers to adopting recommendations to prevent childhood obesity: results of a focus group study with parents. BMC Pediatr. 2009;9:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-9-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Styles J.L., Meier A., Sutherland L.A., Campbell M.K. Parents' and caregivers' concerns about obesity in young children: a qualitative study. Fam. Community Health. 2007;30(4):279–295. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000290541.02834.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Twiddy M., Wilson I., Bryant M., Rudolf M. Lessons learned from a family-focused weight management intervention for obese and overweight children. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(7):1310–1317. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011003211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schalkwijk A.A., Bot S.D., de Vries L., Westerman M.J., Nijpels G., Elders P.J. Perspectives of obese children and their parents on lifestyle behavior change: a qualitative study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015;12:102. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0263-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown C.W., Alexander D.S., Warren C.A., Anderson-Booker M. A qualitative approach: evaluating the childhood health and obesity initiative communities empowered for success (CHOICES) pilot study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(4):549–557. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heerman W.J., Teeters L., Sommer E.C., Burgess L.E., Escarfuller J., VanWyk C., Barkin S.L., Duhon A., Cole J., Samuels L.R., Singer-Gabella M. Competency-based approaches to community health: a randomized controlled trial to reduce childhood obesity among Latino preschool-aged children. Child. Obes. 2019;(Aug 5) doi: 10.1089/chi.2019.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heerman W.J., Burgess L.E., Escarfuller J., Teeters L., Slesur L., Liu J., Qi A., Samuels L.R., Singer-Gabella M. Competency Based Approach to Community Health (COACH): the methods of a family-centered, community-based, individually adaptive obesity randomized trial for pre-school child-parent pairs. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2018;73:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heerman W.J., Burgess L.E., Escarfuller J., Teeters L., Slesur L., Liu J., Qi A., Samuels L.R., Singer-Gabella M. Competency Based Approach to Community Health (COACH): the methods of a family-centered, community-based, individually adaptive obesity randomized trial for pre-school child-parent pairs. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2018;73:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.08.006. October. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton M.Q. third ed. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, Calif: 2002. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charmaz K. Sage Publications; London ; Thousand Oaks, Calif.: 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutiérrez K.D., Rogoff B. Cultural ways of learning: individual traits or repertoires of practice. Educ. Res. 2003;32(5):19–25. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.