Abstract

Introduction

The objective of this study was to investigate and compare optic nerve and retinal layers in eyes of patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) with paired control eyes using optical coherence tomography.

Methods

Sixty-three eyes of 34 subjects, 12 eyes with AD and 51 eyes with MCI, positive to 11C-labeled Pittsburgh Compound-B with positron emission tomography (11C-PiB PET/CT), and the same number of sex- and age-paired control eyes underwent optical coherence tomography scanning analyzing retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL), ganglion cell layer (GCL), Bruch's membrane opening–minimum rim width (BMO-MRW), inner plexiform layer (IPL), outer nuclear layer, and lamina cribrosa (LC).

Results

Compared with healthy controls, eyes of patients with positive 11C-PiB PET/CT showed a significant thinning of RNFL (P < .028) and GCL (P < .014). IPL and outer nuclear layer also showed significant thinning in two (P < .025) and one location (P < .010), respectively. No significant differences were found when optic nerve measurements BMO-MRW and LC were compared (P > .131 and P > .721, respectively). Temporal sector GCL, average RNFL, and temporal sector RNFL also exhibited significant thinning when MCI and control eyes were compared (P = .015, P = .005 and P = .050, respectively), and also the greatest area under the curve values (0.689, 0.647, and 0.659, respectively). GCL, IPL, and RNFL tend to be thinner in the AD group compared with healthy controls.

Discussion

Our study suggests that RNFL and GCL are useful for potential screening in the early diagnosis of AD. LC and BMO-MRW appear not to be affected by AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, retinal nerve fiber layer, optical coherence tomography, ganglion, ganglion cell layer, positron emission tomography, mild cognitive impairment, lamina cribrosa, bruch's membrane opening–minimum rim width

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a complex neurodegenerative disorder and the leading cause of dementia [1]. Well-known neuropathological hallmarks of AD are intracellular neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau protein (p-Tau) and extracellular amyloid β (Aβ) protein deposits throughout the brain, which distinctly contribute to a definitive diagnosis of AD [2]. These neuropathological changes are believed to develop 15–20 years before the onset of clinical dementia [3]. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is the prodromal phase of AD, during which objective cognitive problems but no functional impairment are observed [4]. Different in vivo biomarkers have been studied in the early diagnosis of AD [4], leading to the incorporation of three core cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers for AD into modern diagnostic research criteria: the 42–amino acid form of Aβ (Aβ42), total tau (T-tau), and phosphorylated tau (P-tau) [5]. Aβ pathology is detected by decreased Aβ levels in CSF or with positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging using 11C-labeled Pittsburgh Compound-B (11C-PiB) ligand [3], whereas neuronal injury is reflected by either cortical atrophy on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), hypometabolism on fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT (FDG-PET/CT), and other amyloid PET radiotracers, or increased T-tau and/or p-Tau levels in CSF [6], [7]. Nevertheless, current diagnostic modalities for AD are restricted by standardization problems and invasiveness in the case of CSF markers, and high costs and limited availability in the case of amyloid PET [8], [9]. These factors have prompted the investigation of cheaper and less-invasive AD biomarkers.

It has long been recognized that patients with early AD showed visual function impairments [10]. Moreover, several studies using optical coherence tomography (OCT) [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17] to analyze different eye structures have reported retinal and optic nerve changes in patients with AD and MCI. Studies in patients with AD have shown retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thinning [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], retinal ganglion cell layer (GCL) degeneration [12], [15], choroidal thickness changes, and vascular alterations. However, the diagnosis of AD in nearly all studies was made using the Mini–Mental State Examination and was not supported with biomarkers, which might imply a variable degree of case misclassification, affecting statistical power and the interpretation of results.

Lamina cribrosa (LC) has been studied in other neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson's disease [18], but until now, LC has not been measured in AD. Similarly, Bruch's membrane opening–minimum rim width (BMO-MRW) has not been previously measured in patients with AD. This parameter measures the neuroretinal rim from the BMO to the nearest point on the internal limiting membrane, and the shortest distance constitutes a measurement that reduces interindividual variation, while providing higher sensitivity and specificity compared with RNFL in patients with glaucoma [19].

The aim of this study was to assess anatomic variations in the optic nerve and retina of amyloid-positive patients defined by 11C-PiB PET/CT and in age- and gender-matched healthy controls (HCs), using OCT analyses, including RNFL, GCL, LC, and BMO-MRW, for a better understanding of the damage this disease causes in the eye, and to determine the best OCT biomarkers in patients with AD and prodromal MCI. To the best of our knowledge, this might be the first report that analyzes OCT changes in individuals with cognitive impairment and positive 11C-PiB PET/CT, and LC and BMO-MRW in patients with AD.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient/subject groups

We conducted a cross-sectional study of Caucasian patients with MCI and AD compared with cognitively healthy age- and gender-matched controls recruited consecutively from the Neurology and Ophthalmology departments of the University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla (UHMV), between May 2016 and June 2018. HCs were matched with MCI and AD separately and with both groups together. Indeed, AD and MCI were compared.

HCs were volunteers recruited among the family members of patients attending the ophthalmology clinic with a complaint of dry eye. They were n'ot screened with neuropsychological tests or 11C-PiB PET/CT.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the UHMV, and it was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent forms were signed by all participants before the examinations.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All patients met research diagnostic criteria for AD and MCI [20]. Cases were confirmed in the neurology clinic as part of the Valdecilla Cohort for Memory and Brain Aging, a prospective study to evaluate early disease changes in nondemented individuals. Patients older than 55 years with a classic (amnesic) clinical presentation of AD or MCI and positive 11C-PiB PET/CT scan were recruited. Diagnoses were established by a clinical committee of four neurologists (S.L.-G., P.S.-J., E.R.-R., and C.L.) and two neuropsychologists (A.P., M.G.-M.). All patients were assessed by a multidisciplinary team to exclude other neurological or psychiatric etiologies. Structural neuroimaging with CT or MRI was performed. All participants underwent a comprehensive neuropsychological battery conducted by two trained neuropsychologists (A.P., M.G.-M.), that included the main cognitive domains (memory, language, praxis, visual perception, and frontal functions). All patients underwent 11C-PiB PET/CT at the Nuclear Medicine Department of the UHMV. 11C-PiB synthesis and image acquisition have been described elsewhere [21]. PET/CT scans were visually interpreted by two experienced nuclear medicine specialists (J.J.-B., I.B.) as positive or negative for cortical PiB uptake.

Exclusion criteria included a refractive error >6.0 diopters (D) of spherical equivalent or 3.0 D of astigmatism, any history of ocular surgery, ocular disease, best-corrected visual acuity as poor as 20/40, intraocular pressure (IOP) ≥ 18 mm Hg, past history of raised IOP, neuroretinal rim notching, or optic disc hemorrhages. Similarly, other exclusion criteria included clinically relevant opacities of the optic media and low-quality images due to unstable fixation, or severe cataract (patients with mild to moderate cataract might be enrolled in the study, but only high-quality images were included). Subjects with a history of neurological or psychiatric disorder, any significant systemic illness, poor collaboration due to neurological dementia stage or unstable medical condition (e.g., active cardiovascular disease), and current use of any medications known to affect cognition (e.g., use of sedative narcotics) were also excluded.

2.3. Ophthalmic assessment

All subjects underwent a thorough ophthalmic examination on the day of OCT imaging, including best-corrected visual acuity (Snellen charts), refraction, IOP measurement with Goldmann applanation tonometer, anterior segment biomicroscopy, and dilated fundus examination. The refractive error was recorded using an Autorefractometer Canon RK-F1 (Canon USA Inc., Lake Success, NY, USA). Axial length was measured by Lenstar LS 900 (Haag-Streit AG, Köniz, Switzerland).

Each patient was randomized to decide which eye was to be examined first, using the method described by Dulku [22].

2.4. Optical coherence tomography imaging

A single, well-trained ophthalmologist (A.C.), who was masked to the diagnosis of the patients, performed all OCT examinations. Participants received one drop of tropicamide 1% and phenylephrine per eye for pupil dilation before OCT imaging.

Retinal thickness was measured with spectral-domain (SD) Spectralis SD-OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) using the images obtained by posterior pole analysis scan. Using this protocol, the OCT instrument automatically delineates a line joining the center of the fovea and the center of the optic disc as a reference line. Thereupon, 61-line scans (1024 A scans/line) parallel to the central reference line are recorded. The quality of the scans is indicated on a color scale at the bottom of the scanned images. Only scans in the green range were considered of sufficiently good quality for inclusion in this study. The automatic real-time tracking of these scans was 25. A masked investigator (A.L.-de-E.) examined all images of each eye to identify any segmentation or centered errors in the images. The average retinal layer measurement of each 3° x 3° sector was determined, which made up the 4 sectors (superior, temporal, inferior, and nasal). Segmentation analysis was performed using Heidelberg segmentation software (version 1.10.2.0) to calculate thickness of the GCL, inner plexiform layer (IPL), and outer nuclear layer (ONL) (Fig. 1A) considering APOSTEL recommendations [23].

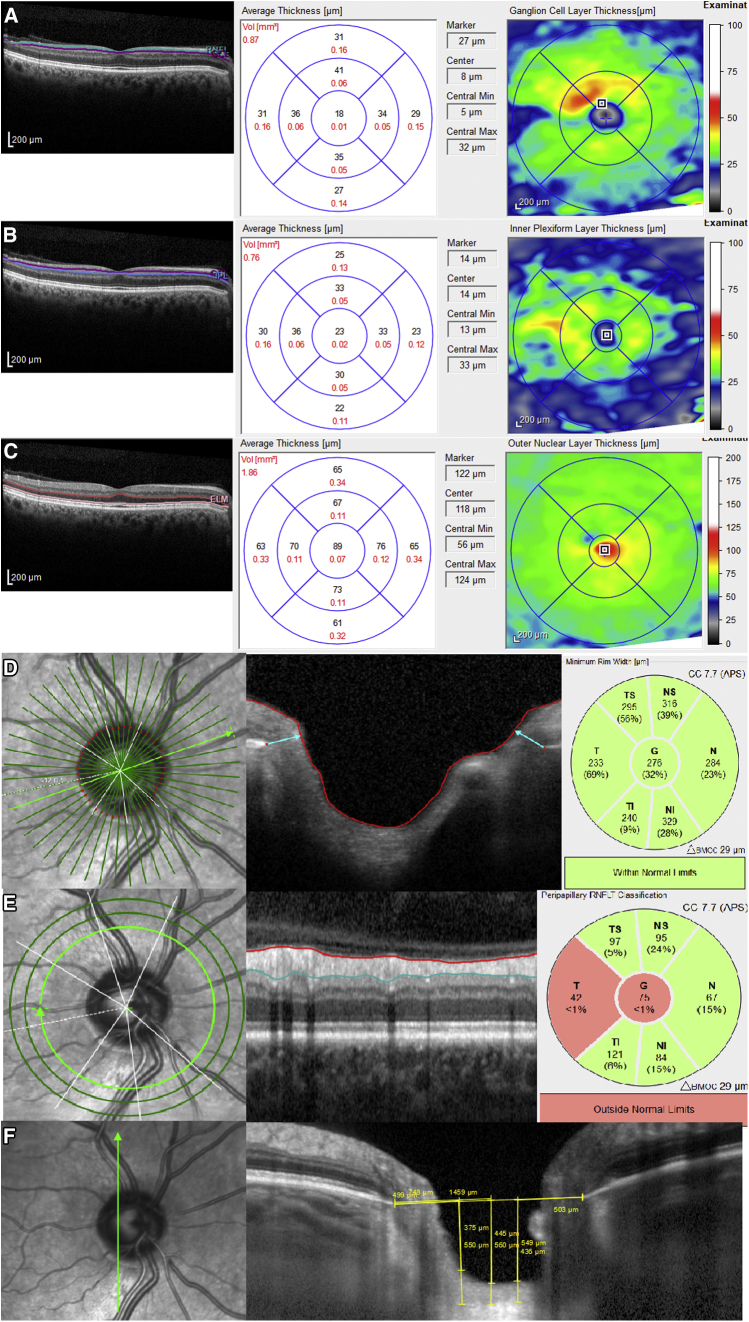

Fig. 1.

A representation of retinal layers and optic nerve changes that could be depicted in AD by optical coherence tomography (OCT) in a 67-year-old man. The software automatically marked the following layers in a single horizontal foveal scan: (A) ganglion cell layer (GCL) analysis showing a diffuse decrease in all sectors, (B) reduced inner plexiform layer (IPL) thicknesses, and (C) outer nuclear layer (ONL) thinning. (D) Bruch's membrane opening–minimum rim width (BMO-MRW) showing neither diffuse damage nor sector decrease. (E) Reduced retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness; in this case, diffuse RNFL thinning is supported, due in particular to temporal sector damage. (F) The anterior surface of the lamina cribrosa (LC), performed by vertical scan next to the optic nerve head center, is not damaged. Abbreviation: AD, Alzheimer's disease.

The new GMP Edition provided by Spectralis 6.0c version was used, including 24 radial and 3 circular scans. BMO-based MRW is automatically centered at the optic nerve head, and 24 radial B-scans were acquired over a 15° area. The shortest distance from each identified BMO point to the internal limiting membrane (Fig. 1B) was measured. After image acquisition, the BMO segmentation was reviewed and confirmed by a trained examiner (A.C.). RNFL thickness measurements of each individual eye were normalized for anatomic orientation of the fovea to optic nerve to an accurate and consistent positioning of the RNFL thickness measurement across eyes (automatic real-time tracking mean 100). Although the new module includes 3 circle scans (inner circle: 3.5 mm, middle circle: 4.1 mm, and outer circle: 4.7 mm), we registered only the figures provided by the inner circle scan (standard) (Fig. 1C). Six sector areas (superotemporal, superior, superonasal, inferonasal, inferior, and inferotemporal) and the average were measured in both analyses.

LC was measured by performing one vertical scan closest to the optic nerve head center, at the point where the visibility of the anterior LC surface was as complete as possible, by excluding the main vessels using enhanced depth image technology, with an average of over 100 scans using the automatic averaging mode. A reference line connecting the two Bruch's membrane end points was drawn, and three equidistant points (inferior, middle, and superior), corresponding to one-third and one-half of this reference, were matched to the anterior prelaminar tissue surface and anterior LC surface (Fig. 1D). Prelaminar tissue thickness (PTT) and anterior LC surface depth were measured at the three aforementioned points. PTT was defined as the distance between the anterior prelaminar tissue surface and anterior LC surface. Anterior LC surface depth was determined by measuring the distance from the reference line to the level of the anterior LC surface. Measurements were made using the SPECTRALIS software manual caliper tool by the aforementioned masked investigators (A.L.-de-E., A.C.).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Student's t-test for dependent samples was used to compare RNFL, BMO-MRW, and GCL between patients with AD and healthy gender- and age-matched controls. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to evaluate interobserver reproducibility in LC measurements and consequently the reliability of the results of the measurements that were manually quantified.

A receiver operating characteristic curve was used to assess the discrimination value of the OCT analyses. We used the area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUCs) to assess the ability of GCL and RNFL thicknesses to discriminate AD, MCI, and AD/MCI from HC [24]. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.20.0 (International Business Machine Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

2.6. Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the main manuscript and its supplementary information files.

3. Results

In total, 51 MCI eyes and 12 AD eyes from 34 patients, and 63 eyes from 32 HCs were included in the final analysis on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Five PiB+ eyes were omitted because of poor collaboration.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with AD and controls showed no significant differences between both groups, see Table 1. Mean age was 73.5 ± 6.0 years (age range: 57–85 years). All eyes included were phakic.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical participant's characteristics (63 eyes of 34 individuals)

| Variables | Patients (N = 63) | Controls (N = 63) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 73.5 (6.0) | 73.28 (6.0) | .998 |

| Male eyes (%) | 31 (49.2) | 31 (49.2) | 1 |

| Spherical equivalent (Diopters) | 0.53 (1.10) | 0.58 (1.22) | .797 |

| BCVA | 20/29 (0.34) | 20/26 (0.17) | .259 |

| Axial length (mm) | 23.2 (0.8) | 23.2 (0.9) | .816 |

| IOP | 13.7 (3.9) | 12.8 (2.8) | .154 |

NOTE. Data for quantitative variables are shown as mean (standard deviation).

Sex differences were assessed with Fisher's test. Rest of analysis was performed using paired Student's t-test for dependent samples. Patients means mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients altogether.

Abbreviations: BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; IOP, intraocular pressure.

Table 2 shows the relationship of RNFL, BMO-MRW, ONL, IPL, and GCL with PiB+, MCI, AD, and the cognitively healthy control group (HC).

Table 2.

Comparison of different optical coherence tomography analysis between patients and control eyes; mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients and control eyes and Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients and controls

| Variables | Patients (N = 63) | Controls (N = 63) | P | MCI (N = 51) | Controls (N = 51) | P | AD (N = 12) | Controls (N = 12) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average RNFL thickness | 97.7 (11,6) | 99.9 (8.2) | .004∗ | 93.7 (12.5) | 99.5 (8.1) | .005∗ | 99.4 (5.1) | 102.0 (9.3) | .482 |

| RNFL temporal | 66.5 (9.0) | 71.3 (10.2) | .028∗ | 65.9 (9.4) | 70.9 (10.7) | .050∗ | 70.0 (6.2) | 74.1 (5.8) | .312 |

| RNFL temporal-superior | 118.8 (16.6) | 127.4 (17.4) | .019∗ | 119.5 (16.3) | 127.3 (17.3) | .062 | 115.0 (19.0) | 128.3 (19.1) | .080 |

| RNFL temporal-inferior | 139.4 (20.8) | 149.8 (15.8) | .004∗ | 139.5 (22.0) | 149.0 (15.1) | .018∗ | 138.7 (10.4) | 153.7 (19.6) | .062 |

| RNFL nasal | 80.5 (17.8) | 81.7 (15.2) | .673 | 79.6 (18.3) | 80.1 (15.5) | .875 | 85.2 (14.4) | 90.4 (10.5) | .386 |

| RNFL nasal-superior | 111.3 (22.6) | 117.3 (25.8) | .201 | 108.9 (22.1) | 117.4 (25.5) | .090 | 124.3 (22.1) | 166.6 (20.1) | .571 |

| RNFL nasal-inferior | 105.5 (29.6) | 114.0 (18.0) | .062 | 109.7 (27.4) | 114.5 (16.8) | .275 | 83.0 (33.1) | 111.4 (24.9) | .100 |

| Average BMO-MRW | 290.3 (54.1) | 303.5 (54.6) | .263 | 281.9 (49.9) | 309.4 (54.9) | .027∗ | 326.8 (58.8) | 278.8 (47.3) | .106 |

| BMO-MRW temporal | 208.9 (49.9) | 203.3 (43.5) | .649 | 207.7 (52.8) | 205.4 (46.1) | .878 | 214.2 (27.6) | 193.8 (30.5) | .012∗ |

| BMO-MRW temporal-superior | 272.4 (64.2) | 291.9 (49.8) | .231 | 272.2 (70.1) | 295.2 (53.6) | .240 | 273.3 (28.8) | 276.8 (24.7) | .848 |

| BMO-MRW temporal-inferior | 286.2 (67.5) | 315.6 (64.6) | .131 | 277.6 (69.7) | 317.4 (64.9) | .091 | 324.6 (41.2) | 307.6 (68.8) | .267 |

| BMO-MRW nasal | 319.8 (65.5) | 325.2 (60.4) | .735 | 305.5 (55.2) | 327.3 (61.7) | .202 | 383.6 (74.9) | 315.5 (58.7) | .095 |

| BMO-MRW nasal-superior | 328.0 (75.0) | 347.2 (54.7) | .323 | 322.4 (74.9) | 348.1 (53.2) | .237 | 353.0 (76.3) | 343.3 (66.5) | .845 |

| BMO-MRW nasal-inferior | 348.3 (63.6) | 371.0 (59.1) | .138 | 342.2 (61.8) | 372.6 (61.3) | .089 | 375.6 (69.8) | 363.8 (52.0) | .657 |

| GCL superior | 47.5 (9.1) | 51.8 (5.6) | .006∗ | 48.3 (7.1) | 51.0 (5.5) | .057 | 44.3 (14.9) | 55.2 (5.4) | .050∗ |

| GCL inferior | 46.5 (9.8) | 50.9 (6.0) | .008∗ | 47.1 (8.5) | 50.2 (6.1) | .052 | 44.2 (14.4) | 53.7 (4.5) | .078 |

| GCL temporal | 41.7 (9.5) | 46.7 (5.8) | .002∗ | 42.2 (8.4) | 46.1 (6.1) | .015∗ | 39.6 (13.4) | 49.1 (4.3) | .074 |

| GCL nasal | 46.5 (9.3) | 50.5 (6.4) | .014∗ | 47.3 (7.8) | 50.1 (6.6) | .089 | 43.3 (14.2) | 52.7 (5.1) | .078 |

| IPL superior | 39.0 (4.3) | 41.1 (3.6) | .011∗ | 39.1 (4.4) | 40.5 (3.2) | .097 | 38.8 (4.1) | 44.0 (3.9) | .026∗ |

| IPL inferior | 38.6 (4.3) | 40.1 (3.7) | .066 | 38.5 (4.5) | 39.6 (3.7) | .268 | 38.8 (2.9) | 42.4 (2.5) | .007∗ |

| IPL temporal | 39.6 (4.1) | 40.8 (3.6) | .111 | 39.6 (4.1) | 40.3 (3.3) | .421 | 39.2 (3.8) | 43.0 (4.1) | .044∗ |

| IPL nasal | 39.8 (3.9) | 41.4 (3.5) | .025∗ | 39.7 (4.1) | 41.0 (3.4) | .138 | 39.7 (3.3) | 43.3 (3.0) | .009∗ |

| ONL superior | 63.4 (11.7) | 68.9 (10.7) | .010∗ | 63.3 (11.6) | 68.1 (11.3) | .048∗ | 63.5 (12.3) | 72.7 (5.8) | .058 |

| ONL inferior | 60.7 (15.2) | 63.5 (12.2) | .344 | 60.3 (14.5) | 63.5 (12.7) | .296 | 62.5 (18.4) | 63.1 (10.0) | .947 |

| ONL temporal | 69.4 (10.2) | 72.7 (10.3) | .072 | 68.6 (10.5) | 72.2 (10.8) | .100 | 72.9 (7.8) | 75.0 (6.7) | .442 |

| ONL nasal | 68.3 (15.3) | 72.2 (11.8) | .156 | 68.2 (15.1) | 72.2 (11.6) | .166 | 68.3 (16.9) | 72.0 (13.2) | .676 |

NOTE. Data for quantitative variables are shown as mean (standard deviation). Analysis was performed using paired Student's t-test for dependent samples.

Patients means mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer disease (AD) patients altogether.

Abbreviations: RNFL, retinal nerve fiber layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer; BMO-MRW, Bruch's membrane opening–minimum rim width; IPL. inner plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer.

P value < .005.

GCL thickness showed a significant reduction across the MCI group in the temporal sector compared with the HC group (42.2 ± 8.4 μm in MCI and 46.1 ± 6.1 μm in HC; P = .015). Compared with HCs, patients with AD had GCL thickness reduction significantly in the superior sector (44.3 ± 14.9 μm in AD and 55.2 ± 5.4 μm in HC; P = .050). More significant differences were identified when both groups (MCI and AD) were compared with controls, including significant thinning of GCL in all locations (P < .014).

IPL was significantly reduced in the superior and nasal regions in the PiB+ group (P = .011 and P = .025, respectively) and in all superior, inferior, temporal, and nasal sectors in the AD group (P = .026, P = .007, P = .044, P = .009; respectively), whereas the results in the MCI group were not significant.

ONL showed significant changes in the superior sector in the MCI group (63.3 ± 11.6 μm in MCI and 68.1 ± 11.3 μm in HC; P = .048) and in the PiB+ group (P = .010).

Average RNFL thickness and temporal-inferior quadrant and temporal quadrant RNFL thickness were significantly reduced in MCI compared with control eyes (P = .005, P = .018, P = .050; respectively). Once more, the comparison between the PiB+ group (MCI and AD subjects) and control eyes supports the aforementioned outcomes, but with greater statistical power (average RNFL P = .004, temporal P = .028, temporal inferior P = .004) and provides new information with regard to a significant thinning of temporal superior sector RNFL (P = .019).

Average BMO-MRW was significantly reduced in MCI (P = .027) and also thinner in PiB+ subjects (290.3 ± 54.1 μm) than in HCs (303.5 ± 54.6 μm). Nevertheless, no statistical significance was found in the latter group or in average BMO-MRW (P = .263), even when the 6 BMO-MRW sectors were compared (P > .131).

The study revealed no statistically significant differences in LC parameters between the PiB+ and control group.

ICCs were 0.974, 0.993, and 0.978 for superior, central, and inferior LC surface depth, respectively. Similarly, ICCs were >0.992 for PTT measurements, as depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) used to determine interobserver reproducibility of manually quantified measurements

| Variables | ICC |

|---|---|

| LCD S | .974 |

| LCD C | .993 |

| LCD I | .978 |

| PTT S | .992 |

| PTT C | .996 |

| PTT I | .995 |

Abbreviations: S, superior; I, inferior; PTT, prelaminar tissue thickness; LCD, anterior LC surface depth.

We also analyzed OCT results comparing MCI and AD subjects (see Table 4). Although no significant differences were found, the measurements tended to be thinner in the AD group than in the MCI group, GCL in particular.

Table 4.

Comparison of different optical coherence tomography analysis between mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) eyes

| Variables | MCI (N = 51) | AD (N = 12) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average RNFL thickness | 93.7 (12.5) | 99.4 (5.1) | .155 |

| RNFL temporal | 65.9 (9.4) | 70.0 (6.2) | .411 |

| RNFL temporal-superior | 119.5 (16.3) | 115.0 (19.0) | .793 |

| RNFL temporal-inferior | 139.5 (22.0) | 138.7 (10.4) | .774 |

| RNFL nasal | 79.6 (18.3) | 85.2 (14.4) | .653 |

| RNFL nasal-superior | 108.9 (22.1) | 124.3 (22.1) | .060 |

| RNFL nasal-inferior | 109.7 (27.4) | 83.0 (33.71) | .045∗ |

| Average BMO-MRW | 281.9 (49.9) | 326.8 (58.8) | .016∗ |

| BMO-MRW temporal | 207.7 (52.8) | 214.2 (27.6) | .740 |

| BMO-MRW temporal-superior | 272.2 (70.1) | 273.3 (28.8) | .984 |

| BMO-MRW temporal-inferior | 277.6 (69.7) | 324.6 (41.2) | .126 |

| BMO-MRW nasal | 305.5 (55.2) | 383.6 (74.9) | .006∗ |

| BMO-MRW nasal-superior | 322.4 (74.9) | 353.0 (76.3) | .392 |

| BMO-MRW nasal-inferior | 342.2 (61.8) | 375.6 (69.8) | .245 |

| GCL superior | 48.3 (7.1) | 44.3 (14.9) | .174 |

| GCL inferior | 47.1 (8.5) | 44.2 (14.4) | .365 |

| GCL temporal | 42.2 (8.4) | 39.6 (13.4) | .384 |

| GCL nasal | 47.3 (7.8) | 43.3 (14.2) | .185 |

| IPL superior | 39.1 (4.4) | 38.8 (4.1) | .852 |

| IPL inferior | 38.5 (4.5) | 38.8 (2.9) | .890 |

| IPL temporal | 39.6 (4.1) | 39.2 (3.8) | .740 |

| IPL nasal | 39.7 (4.1) | 39.7 (3.3) | .944 |

| ONL superior | 63.3 (11.6) | 63.5 (12.3) | .086 |

| ONL inferior | 60.3 (14.5) | 62.5 (18.4) | .652 |

| ONL temporal | 68.6 (10.5) | 72.9 (7.8) | .203 |

| ONL nasal | 68.2 (15.1) | 68.3 (16.9) | .923 |

NOTE. Data for quantitative variables are shown as mean (standard deviation). Analysis was performed using paired Student's t-test for dependent samples.

Abbreviations: RNFL, retinal nerve fiber layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer; BMO-MRW, Bruch's membrane opening–minimum rim width; IPL, inner plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer.

P value < .005.

Table 5 shows the receiver operating characteristic AUC analysis of different OCT measurements with 95% confidence limits for sensitivity and specificity. Higher AUC values correlating with a diagnosis of MCI were observed for average, temporal, and temporal superior RNFL (0.652, 0.660, and 0.666; respectively) and temporal sector GCL (0.699).

Table 5.

Area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC)

| Variables | AUC | P |

|---|---|---|

| Average RNFL thickness | .652 | .015 |

| RNFL Temporal | .660 | .010 |

| RNFL Temporal-superior | .666 | .008 |

| RNFL Temporal-inferior | .641 | .024 |

| RNFL Nasal | .554 | .382 |

| RNFL Nasal-superior | .570 | .264 |

| RNFL Nasal-inferior | .488 | .844 |

| Average BMO-MRW | .616 | .063 |

| GCL superior | .668 | .007 |

| GCL inferior | .677 | .005 |

| GCL temporal | .699 | .001 |

| GCL nasal | .660 | .010 |

| IPL superior | .666 | .008 |

| IPL inferior | .629 | .039 |

| IPL temporal | .612 | .072 |

| IPL nasal | .662 | .010 |

| ONL superior | .668 | .007 |

| ONL inferior | .554 | .369 |

| ONL temporal | .670 | .006 |

| ONL nasal | .539 | .634 |

NOTE. Analysis with 95% confidence limits for sensitivity and specificity of different optical coherence tomography parameter analysis in mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Bold values represent the high AUC result.

Abbreviations: RNFL, retinal nerve fiber layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer; BMO-MRW, Bruch's membrane opening–minimum rim width; IPL, inter plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer.

4. Discussion

In vivo anatomical studies have provided further evidence of direct involvement of the retina, choroid, and optic nerve head in patients with AD [12]. For this reason, we used SD-OCT to compare RNFL, GCL, LC, and rim analysis between patients with brain amyloid accumulation PiB+ (MCI and AD) and HC. Our study included highly characterized patients with detailed neurocognitive testing and PET imaging with 11C-PiB ligand analysis that could readily differentiate between participants with normal cognition from dementia due to AD, as previously reported [6], [7]. PiB imaging has many potential clinical benefits, such as preclinical detection of AD and an accurate differentiation of AD from dementias of other etiologies.

In our study, RNFL and GCL were significantly thinner in MCI and AD subjects compared with HC assessed by SD-OCT. Our results strongly suggest that retinal ganglion cells and optic nerve axonal damage can be clinically detected in prodromal AD.

Several studies have previously reported a significant decrease in mean overall RNFL thickness in patients with AD, generating interest in the use of this parameter as a biomarker for early detection of AD. Initially, evidence of average RNFL thinning in patients with AD was demonstrated with time domain OCT [17], [25] and has subsequently been confirmed by several independent groups using various modern OCT devices, such as spectral-domain (SD) OCT [14], [15], [16], [26], [27]. Findings were supported by three meta-analyses [26], [28]. Differences in the most affected peripapillary quadrants, such as superior sector RNFL [19], [29] and both superior and inferior sector RNFL [29], were later reported. Our findings agreed with previous clinical studies that reported a lower average RNFL in the PiB+ group, particularly in the superior and inferior quadrant, compared with HC.

However, den Haan et al. [30] have recently reported that neither macular nor RNFL thicknesses are reduced in patients with AD. We believe that this might be due to the exclusion criteria used by these authors, as they excluded patients with optic nerve anomalies assessed with Heidelberg Retinal Tomography, to avoid enrolling patients with glaucoma. However, patients with optic nerve damage due to AD may also have been ruled out by these criteria. The criterion we used to exclude patients with glaucoma was IOP >18 mm Hg or patients receiving glaucoma treatment, similar to other publications [27], [30], [31].

Average RNFL reduction was recently shown not only in AD subjects but also in MCI compared with controls, and some authors found that RNFL thickness was significantly lower in AD than MCI [32], whereas other groups did not observe statistical significantly differences between MCI and AD patients [17], [33]. In our study, we found no statistical differences between AD and MCI patients, but interestingly, the study revealed GCL reduction in all sectors in AD compared to MCI, supporting the idea of correlation between the duration of the disease and macular thinning and optic nerve disease.

If optic nerve damage, displayed as RNFL thinning, is assumed in PiB+ patients and might begin there, we hypothesized that BMO-MRW or LC optic nerve structures should be thinned in those patients. In glaucoma, OCT-derived BMO-MRW analysis provides significantly greater sensitivity [34] and specificity [19] than RNFL, so by this argument, we presumed that BMO-MRW analysis might also be more sensitive in assessing optic nerve damage in AD. We found a significant reduction in average BMO-MRW in the MCI group compared with HC, but no significant thinning was described either in PiB+ or in AD patients compared with HC. Similarly, we found no significant reductions in LC thickness.

We therefore presume that ocular damage might start in the GCL [35]. Macular GCL-IPL reflects the thickness of retinal ganglion cell bodies and dendrites in the retina. In 1986, Hinton et al. [13] provided histopathological evidence of optic neuropathy and degeneration of retinal ganglion cells in AD subjects, and later, in a postmortem study, substantial GCL degeneration was demonstrated in the foveal/parafoveal region in AD. OCT imaging in vivo first showed decreased total macular thickness in AD subjects [16], [31] and later, when macular segmentation was available, Marziani et al. reported significant reductions in combined RNFL and GCL thickness (RNFL+GCL+IPL) in the macular region [15]. Nevertheless, Cheung et al. [33] suggested that including the RNFL in the GCL analysis in the macular area may influence the sensitivity for revealing GCL abnormalities, so they measured GCL-IPL without including the RNFL and found significant GCL-IPL thinning in AD and MCI patients compared with HC. In accordance with the latest reviews, our study revealed that PiB+ patients had significant GCL thickness reduction, mainly in the temporal sector (P < .014) and adds the knowledge that GCL is more affected by thinning than RNFL in MCI subjects. We also found significant IPL thinning in all sectors in AD subjects compared with HC.

Recently, Koronyo et al. [36] described classic plaques of extracellular Aβ deposits in the retina of patients with AD in vitro and marked GCL, INL, and ONL loss in the retinas of patients with AD compared with retinas of matched controls. Our results reflect these findings, as we found significant GCL thinning in the four sectors. On the contrary, some in vivo studies displayed controversial GCL measurements using SD-OCT, reporting that RNFL and GCL thickness were unable to distinguish AD dementia from MCI and normal controls in clinically well-characterized series [37], [38]. The authors themselves hypothesized that a larger series would be necessary to delineate significant differences between the groups studied. In our opinion, their study has methodological limitations. Although PET imaging was performed as an inclusion criterion for AD, neither the ligand used nor the imaging result are detailed. Furthermore, patients with glaucoma were excluded, but the criteria for exclusion are not clearly or correctly described.

Our study has several limitations. The number of patients is small and the design is cross-sectional. Future studies should include more subjects with early-stage AD and late-stage AD, longitudinal measurements, and disease-specific imaging aimed at detecting retinal amyloid. Correlation with volumetric MRI data (e.g., hippocampus, optical tract, cortical thickness) may add to the understanding of the relationship between retinal and cerebral neuronal loss. Furthermore, one single vertical optical nerve head scan was selected for the morphometric analysis, whereas the remaining peripheral scans were not evaluated. However, only the highest-quality images and the most centered vertical scan without retinal vasculature, in which borders were more clearly visible, were evaluated. Finally, LC thickness was not evaluated because the contour delineation of the posterior LC surface was broadly less accurate than the other structures.

A potential strength of the study is that the research protocol was undertaken in a real clinical setting, so observations from the present study very likely represent day-to-day clinical practice.

This study confirmed RNFL and GCL damage in AD and MCI patients (enrolled with 11C-PiB measurement) leading us to hypothesize that retinal damage is due to Aβ deposition within the retina. It is interestingly reported that macular GCL neuronal loss is more strongly related with MCI than RNFL loss, suggesting that RNFL thinning may not occur until severe stages of AD as a consequence of GCL loss in the macula due to a dense population of those cells in this region. However, more evidence of RNFL thinning in patients with AD exists in the literature, but this might be because RNFL analysis was available before GCL measurement.

Larger, longitudinal studies comparing retinal thickness with biomarkers for amyloid and neuronal injury are required to elucidate the utility of retinal and optic nerve thickness as a screening test and/or prognostic biomarker in early-onset AD.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: The authors reviewed the literature using traditional (e.g., PubMed). Although several studies using optical coherence tomography (OCT) to analyze eye structures have reported retinal and optic nerve changes in Alzheimer's disease (AD), to the best of our knowledge, this might be the first report that analyzes OCT changes in individuals with cognitive impairment and positive 11C-PiB PET/CT. Even more, this study assessed lamina cribrosa and Bruch's membrane opening–minimum rim width in patients with AD.

-

2.

Interpretation: Our findings confirm OCT damage in patients with AD and led to an integrated hypothesis describing the pathophysiology of AD.

-

3.

Future directions: The article hypothesizes that retinal damage is due to Aβ deposition within the retina and proposes a framework for the generation of new hypotheses and the conduct of additional studies. It is interestingly reported that macular neuronal loss is more strongly related with early AD than retinal nerve fiber layer loss.

Acknowledgments

P.S.J. was supported by grants from IDIVAL, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Fondo de Investigación Sanitario, PI08/0139, PI12/02288, PI16/01652), JPND (DEMTEST PI11/03028) and the CIBERNED program and Siemens Healthineers (Valdecilla Cohort for Memory and Brain Aging).

A.C. conducted the statistical analysis.

The authors would like to thank all the patients and relatives for their generous collaboration.

Footnotes

This study was not sponsored. A.L.-de-E., C.L., S.L.-G., A.P., M.G.-M., M.K., M.B., M.de.A-T, J.J.-B., A.C., and E.R.-R. report no disclosures. P.S.-J. was supported by grants from IDIVAL, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Fondo de Investigación Sanitario, PI08/0139, PI12/02288, PI16/01652), JPND (DEMTEST PI11/03028) and the CIBERNED program, and Siemens Healthineers (Valdecilla Cohort for Memory and Brain Aging). A.C. was supported by grants from IDIVAL.

References

- 1.Alzheimer's Association Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:459–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jack C.R., Kawas C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang S., Jeong H., Baek J.H., Lee S.J., Han S.H., Cho H.J. PiB-PET imaging-based serum proteome profiles predict mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;53:1563–1576. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sperling R.A., Aisen P.S., Beckett L.A., Bennett D.A., Craft S., Fagan A.M. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsson B., Lautner R., Andreasson U., Öhrfelt A., Portelius Erik, Bjerke E. CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:673–684. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Souza L.C., Chupin M., Lamari F., Jardel C., Leclercq D., Colliot O. CSF tau markers are correlated with hippocampal volume in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:1253–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tapiola T., Alafuzoff I., Herukka S.K., Parkkinen L., Hartikainen P., Soininen H. Cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 42 and tau proteins as biomarkers of Alzheimer-type pathologic changes in the brain. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:382–389. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan T.K., Alkon D.L. Alzheimer's disease cerebrospinal fluid and neuroimaging biomarkers: diagnostic accuracy and relationship to drug efficacy. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46:817–836. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tu P., Fu H., Cui M. Compounds for imaging amyloid-β deposits in an Alzheimer's brain: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2015;25:413–423. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2015.1007953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart N.J., Koronyo Y., Black K.L., Koronyo-Hamaoui M. Ocular indicators of Alzheimer's: exploring disease in the retina. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132:767–787. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1613-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayhan H.A., Aslan Bayhan S., Celikbilek A., Tanık N., Gürdal C. Evaluation of the chorioretinal thickness changes in Alzheimer's disease using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;43:145–151. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanks J.C., Schmidt S.Y., Torigoe Y., Porrello K.V., Hinton D.R., Blanks R.H. Retinal pathology in Alzheimer's disease. II. Regional neuron loss and glial changes in GCL. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17:385–395. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(96)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinton D.R., Sadun A.A., Blanks J.C., Miller C.A. Optic-nerve degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:485–487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198608213150804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirbas S., Turkyilmaz K., Anlar O., Tufekci A., Durmus M. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in patients with Alzheimer disease. J Neuroophthalmol. 2013;33:58–61. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e318267fd5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marziani E., Pomati S., Ramolfo P., Cigada M., Giani A., Mariani C. Evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell layer thickness in Alzheimer's disease using spectral–domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:5953–5958. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moschos M.M., Markopoulos I., Chatziralli I., Rouvas A., Papageorgiou S.G., Ladas I. Structural and functional impairment of the retina and optic nerve in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:782–788. doi: 10.2174/156720512802455340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paquet C., Boissonnot M., Roger F., Dighiero P., Gil R., Hugon J. Abnormal retinal thickness in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2007;420:97–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eraslan M., Cerman E., Yildiz Balci S., Celiker H., Sahin O., Temel A. The choroid and lamina cribrosa is affected in patients with Parkinson's disease: enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94:e68–e75. doi: 10.1111/aos.12809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rebolleda G., Casado A., Oblanca N., Muñoz-Negrete F.J. The new Bruch's membrane opening-minimum rim width classification improves optical coherence tomography specificity in tilted discs. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:2417–2425. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S120237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubois B., Feldman H.H., Jacova C., DeKosky S.T., Barberger- Gateau P., Cummings J. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:734–746. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jimenez-Bonilla J.F., Banzo I., De Arcocha-Torres M., Quirce R., Martínez-Rodríguez I., Sánchez-Juan P. Amyloid imaging with 11C-PIB in patients with cognitive impairment in a clinical setting: a visual and semiquantitative analysis. Clin Nucl Med. 2016;41:e18–e23. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dulku S. Generating a random sequence of left and right eyes for ophthalmic research. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:6301–6302. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oberwahrenbrock T., Saidha S., Martinez-Lapiscina E.H., Lagreze W.A., Albrecht P. The APOSTEL recommendations for reporting quantitative optical coherence tomography studies. Neurology. 2016;86:2303–2309. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandrekar J. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1315–1316. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ec173d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parisi V., Restuccia R., Fattapposta F., Mina C., Bucci M.G., Pierelli F. Morphological and functional retinal impairment in Alzheimer's disease patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1860–1867. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00620-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zabel P., Kałużny J.J., Wiłkość-Dębczyńska M., Gębska-Tołoczko M., Suwała K., Kucharski R. Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in Patients with Alzheimer's disease: a comparison of eyes of patients with Alzheimer's disease, primary open-angle glaucoma, and preperimetric glaucoma and healthy controls. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:1001–1008. doi: 10.12659/MSM.914889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon J.Y., Yang J.H., Han J.S., Kim D.G. Analysis of the retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2017;31:548–556. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2016.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He X.-F., Liu Y.-T., Peng C., Zhang F., Zhuang S., Zhang J.S. Optical coherence tomography assessed retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in patients with Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2012;5:401–405. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2012.03.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Y., Li Z., Zhang X., Ming B., Jia J., Wang R. Retinal nerve fiber layer structure abnormalities in early Alzheimer's disease: evidence in optical coherence tomography. Neurosci Lett. 2010;480:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.den Haan J., Janssenb S.F., van de Kreekeb J.A., Scheltensa P., Verbraakb F.D., Bouwman F.H. Retinal thickness correlates with parietal cortical atrophy in early-onset Alzheimer's disease and controls. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2017;10:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cunha J.P., Proença R., Dias-Santos A., Almeida R., Águas H., Alves M. OCT in Alzheimer's disease: thinning of the RNFL and superior hemiretina. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;255:1827–1835. doi: 10.1007/s00417-017-3715-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ascaso F., Cruz N., Modrego P., Lopez-Anton R., Santabárbara J., Pascual L.F. Retinal alterations in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: an optical coherence tomography study. J Neurol. 2014;261:1522–1530. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7374-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheung C.Y.L., Ong Y.T., Hilal S., Ikram M.K., Low S., Ong Y.L. Retinal ganglion cell analysis using high-definition optical coherence tomography in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;5:45–56. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Danthurebandara V.M., Sharpe G.P., Hutchison D.M., Denniss J., Nicolela M.T., McKendrick A.M. Enhanced structure-function relationship in glaucoma with an anatomically and geometrically accurate neuroretinal rim measurement. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;56:98–105. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vidinova C.N., Gouguchkova P.T., Vidinov K.N. Ganglion cell complex map for detecting early damage in high tension and normal tension glaucoma. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2016;233:72–78. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1545993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koronyo Y., Biggs D., Barron E., Boyer D.S., Pearlman J.A., Au W.J. Retinal amyloid pathology and proof-of-concept imaging trial in Alzheimer's disease. JCI Insight. 2017;2 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pillai J.A., Bermel R., Bonner-Jackson A., Rae-Grant A., Fernandez H., Bena J. Retinal nerve fiber layer thinning in Alzheimer's disease: a case-control study in comparison to normal aging, Parkinson's disease, and non-Alzheimer's dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016;31:430–436. doi: 10.1177/1533317515628053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lad E.M., Mukherjee D., Stinnett S.S., Cousins S.W., Potter G.G., Burke J.R. Evaluation of inner retinal layers as biomarkers in mild cognitive impairment to moderate Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the main manuscript and its supplementary information files.