Abstract

Chronic musculoskeletal pain in adolescence is a significant public health concern with 3–5% of adolescents suffering from significant pain-related disability. Pain-related fear and avoidance of activities has been found to have a significant influence on pain outcomes in children and adolescents and is a risk factor for less favorable response to treatment. To address this need, we developed graded exposure treatment for youth with chronic pain (GET Living). We describe the rationale, design, and implementation of a two-group randomized controlled trial (RCT) enhanced with single-case experimental design (SCED) methodology with a sample of 74 adolescents with chronic musculosketal pain and their parent caregivers. GET Living includes education, behavioral exposures, and parent intervention jointly delivered by pain psychology and physical therapy providers. The multidisciplinary pain management control group includes pain psychology delivered education and pain self-management skills training (e.g., relaxation, cognitive skills) and separate physical therapy. Assessments include brief daily diaries (baseline to discharge, 7-days at 3-month and 6-month follow-up), comprehensive in-person evaluations at baseline and discharge, and questionnaire across all time points (baseline, discharge, 3-month and 6-month follow-up). Primary outcome is pain-related fear avoidance. Secondary outcome is functional disability. We also outline all additional outcomes, exploratory outcomes, covariates, and implementation measures. The objective is to offer a mechanism-based, targeted intervention to youth with musculoskeletal pain to enhance likelihood of return to function.

Keywords: Chronic pain, Adolescents, Physical therapy, Behavioral exposure, Single-case experimental design

1. Introduction

Chronic musculoskeletal pain in adolescence is a significant public health concern with 3–5% of adolescents suffering from significant pain-related disability [1]. Pain-related fear and avoidance of activities has been found to have a significant influence on pain outcomes in children and adolescents [[2], [3], [4]] and is a risk factor for less favorable response to treatment [3]. In addition to the child's fear of pain, parental fears and avoidance behaviors in the context of their child's pain also contribute to the child's fear and disability levels [5,6]. When parents interpret an adolescent's pain expression through the lens of their own catastrophic appraisals and pain-related fears, they are more likely to engage in maladaptive parenting behaviors (i.e., protective behaviors) [7]. This, in turn, is known to negatively influence adolescent pain-related function [8]. Conversely, when adolescents actively confront negative beliefs and emotional distress associated with activities that are associated with pain (i.e. exposure) and parents encourage adaptive functioning in the presence of pain, dysfunctional pain-related beliefs are challenged and a gradual return to function occurs [6].

Most current psychological and physiotherapeutic treatments for adolescents with chronic pain involve promoting pain coping strategies via psychological interventions, with separate physical therapy prescribed [9]. The debilitating influence of pain-related fear avoidance can interfere with progress in pain coping efforts and engagement in physical therapy, resulting in continued high healthcare utilization without symptomatic improvement [[10], [11], [12]]. Graded in-vivo exposure treatment (GET) targets functional improvement by exposing patients to avoided activities with demonstrated success among adults [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. There is one ongoing randomized controlled trial of multimodal pain rehabilitation for adolescents with chronic musculoskeletal pain in the Netherlands that combines GET and physical therapy [17], but does not specifically target patients with elevated fear avoidance.

For the last decade our group has focused on pain-related fear and avoidance in children, with efforts centered on effective assessment [4,6] and intervention [3,18]. Our first evaluation of GET for youth with chronic pain (GET Living: NCT01974791) was designed as a sequential replicated and randomized baseline single-case experimental design (SCED) with multiple measures and no comparison arm. Using multilevel modeling of daily diary reports, we observed significant decreases in pain-related avoidance and pain intensity with increased pain acceptance at the end of treatment when compared to baseline that maintained at 3- and 6-month follow-up. Moreover, decreases in pain-related fear and catastrophizing were observed at 3-month follow-up compared to baseline, with improvements maintained 6 months after treatment (Simons et al., in revision). Examining questionnaires administered at baseline, discharge and follow-up, functioning was significantly improved at discharge and persisted at 3- and 6-month follow-up (Functional Disability Inventory partial eta² = 0.534; PedsQL School partial eta² = 0.456; Simons et al., in revision). However, GET Living has not been compared to multidisciplinary pain management (MPM) in youth with chronic pain.

Here we present a two-group randomized controlled trial (RCT) enhanced with SCED methodology. The primary aim is to measure changes in pain-related fear avoidance (primary outcome), and functional disability (secondary outcome) for adolescents with chronic musculoskeletal pain when comparing GET Living to MPM.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and setting

Adolescents and a primary caregiver (N = 74) will be recruited from the outpatient Pediatric Pain Management Clinic (PPMC) at Stanford Children's Health (SCH). Adolescents will be eligible to participate if they 1) have musculoskeletal pain (e.g., localized [back, limb] or diffuse), inclusive of complex regional pain syndrome [19], not due to an acute trauma (active sprain or fracture); 2) are between 8 and 17 years old; 3) have moderate to high pain-related fear (Fear of Pain Questionnaire- FOPQ-C] ≥ 35)4; 4) have moderate to high functional disability (Functional Disability Inventory ≥ 13) [20]; and 5) are proficient in the English language. Adolescents will be ineligible to participate if they have 1) significant cognitive impairment (e.g., brain injury) or 2) significant medical or psychiatric problem that would interfere with treatment (e.g., active psychosis, seizures, suicidality). This study is approved by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University (Protocol # 39514) and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03699007).

2.2. Recruitment

Providers (physician, psychologist, physical therapist, nurse practitioner) at Stanford Children's Health will refer patients to GET Living during initial or follow-up clinic visits. Patient families will receive a brochure that describes the program and includes contact information for the study team. Providers will send a completed eligibility checklist for each patient referred to GET Living via secure email to the research team. Additionally, a study flyer and additional brochures will be available in the patient waiting room for patients to self-refer to the study. For each patient, self- or provider-referred to the trial, eligibility for enrollment will be verified by the research team via a brief screening phone call and online screening measures (FOPQ-C and FDI).

2.3. Study design

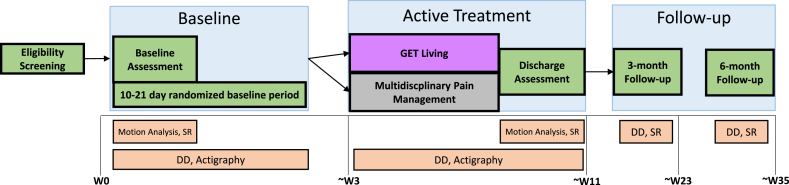

This is a two-arm randomized control trial that is enhanced with a single-case experimental design (SCED) with multiple measures. In single case experiments, a subject is observed repeatedly at different levels of at least one independent variable (e.g., baseline vs. treatment). To accomplish this, patients will be randomly assigned to a pre-treatment/baseline phase of 10–21 days in duration and will complete daily diary measures from Day 0 to end of treatment (Day 0 + N) and for 7-days at 3- and 6-month follow-up. Upon arrival at the first treatment session, patients will be informed if they are assigned to GET Living (i.e., combined PT and Psychology) or MPM (i.e., separate PT and Psychology). The two arms are considered equal treatments, differing only in method of delivery (i.e., combined or separate). The treatment phase consists of 12 sessions (1-h in duration twice a week or 2-h in duration once a week) scheduled over 6–8 weeks. In total, the study will be conducted over the course of 32 months. Twenty-four months will be dedicated to study enrollment, randomization, and completion of the intervention. An additional 8 months will be dedicated to completing 3- and 6-month follow-up assessments (See Fig. 1 for Study Flow).

Fig. 1.

Study Flowchart.Eligibility Screnning: Once a potential adolescent is referred to the GET Living trial, the research coordinator confirms eligibility and schedules the baseline assessment. Baseline: At the baseline assessment the adolescent and parent begin daily diaries, adolescents begin wearing the Actigraph watch, and biomechanical assessment is completed. At the baseline visit the adolescent and parent receive a treatment start date and schedule for sessions (arm allocation is not revealed). Active Treatment: Adolescent and one caregiver/parent present (as developmentally appropriate) for 12 sessions of treatment scheduled over the course of 6–8 weeks, taking into account holidays and vacations. Discharge assessment occurs at the conclusion of treatment. Actigraph is returned to the research team and daily diaries end. Follow-up: Adolescents and parents are sent a battery of questionnaires and daily diaries via REDCap for a 7-day period at 3-month and 6-month follow-up.

2.4. Rationale for study design

RCTs provide estimates of the between-subject treatment response (the average difference between the two groups) but does not provide sufficient data on how a specific individual responds to a given treatment i.e. due to heterogeneity in treatment effects [21]. An individual patient in an RCT could show no improvement, have an adverse reaction to treatment, or benefit from the control (even if the control is shown to be statistically inferior) [22]. Although subgroup analyses are now encouraged in an effort to better elucidate differences in treatment response between individuals, it requires large cohorts of patients for sufficiently powered analyses [23]. For specialized patient groups such as youth suffering from chronic pain, obtaining sufficiently large cohorts for mediation and moderation analyses within the confines of multidisciplinary RCTs is often not feasible. SCED allows the collection of statistically rigorous data at the level of the individual patient. Moreover, such data can be used in meta-analyses of individual effect sizes and multilevel modeling to provide group level results from small and distinctive cohorts.

2.5. Randomization

Randomization schemes are developed and maintained by the study Statistician (DB).

2.5.1. Pre-treatment/baseline randomization

Patients will be randomized to a baseline period of 10–21 days using block randomization with blocks of size twelve in which each baseline period length will be randomly assigned to one patient.

2.5.2. Treatment arm randomization

Following the pre-treatment/baseline phase, patients will be randomized to one of two treatment conditions: GET Living or Multidisciplinary Pain Management (MPM) and will be stratified by pain-related fear (moderate/high; FOPQ-C: moderate [35–49], high [50–96]; derived from validation sample [4] and functional disability (moderate/severe; FDI: moderate [13–29], severe [30–60] [20]); to minimize the probability of imbalance between the two treatment arms. To allow the use of small blocks while minimizing the probability of a blinded staff member predicting the next group allocation, we will use blocks sizes of two and four, which will be randomly chosen. The study biostatistician will create separate randomization lists for each of the four strata prior to the start of patient recruitment with each list long enough to include the total planned study size. A series of block sizes (either two or four, with equal probability weights) will be randomly created and within each block half of the sample will be randomly assigned to GET Living and the other half to MPM. Copies of the randomization lists will be kept by the biostatistician and research coordinator and will not be shared with other members of the team.

2.6. Intervention procedures

Both interventions are provided by a multidisciplinary treatment team which includes a physical therapist (PT) and a pain psychologist. Patient families will be instructed to not initiate other pain treatments from baseline assessment to end of active treatment.. Both treatments consist of 12 1-h patient sessions (1-h in duration twice a week or 2-h in duration once a week) across 6–8 weeks, and 3 parent-only sessions. The primary aim of both treatment arms is to support the patient in returning to valued activities of daily life and restoring daily functioning.

2.7. GET living (see Table 1 for detailed treatment description)

Table 1.

| Session | Topic | Adolescent Content | Parent Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rapport Building, Education, & the Pain Dilemma | Build rapport; obtain patient history; discuss referral impressions and treatment expectations (e.g., increase in functioning vs. pain reduction); using Pain Dilemma, discuss possible life directions toward pain reduction vs. valued activities; discuss negative impact of the Cycle of Avoidance; introduce GET Living paradigm: graded exposure as means to return to valued activities | Joint session: same content |

| 2 | Pain-Worry Cycle & Individualized Formulation | Build rapport; increase program engagement through motivational interviewing strategies; discuss the Fear Avoidance Model (FAM) and Interpersonal FAM (IFAM) to identify unproductive patterns of activity avoidance; resume discussion of GET Living paradigm, introducing pain willingness (attitude) and activity engagement (action) as tenets | Joint session: same content; present parent with Interpersonal FAM to be discussed in future session. |

| 3 | Setting Values-based Treatment Goals | Review FAM and GET Living homework; discuss values and contrast with goals; assist in identification of adolescent's values across various life domains; discuss appropriate goal-setting; assist adolescent in completing values-based goals. | Joint session: same content; assist in identification of parents' own values across various life domains; assist parent in completing values-based goals that support adolescent's values-based goals |

| 4 | Establishing a Fear Hierarchy | Review values-based goals; discuss rationale for exposures using metaphor and exposure graphs; review PHODA results to select activities for upcoming exposure sessions; place valued activities from each life domain upon hierarchy, from least to most worrisome. | Joint session: same content; encourage parent to share any valued activities that are not listed on PHODA for inclusion as needed. |

| 5 | Introduction of WILD scale & Exposure Action Plan | Review completed hierarchy and rationale for exposures, as needed; discuss use of WILD scale; conduct mini-exposure with a mildly worrisome activity; modify activities and offer support as needed; plan Home Based-Exposures (HBEs) | Joint Session: Same Content Parent observes adolescent exposure session, participating as appropriate. Psychology offers further explanation and rationale, as well as support to parent. |

| 6 | Graded Exposure with Behavioral Experiments-1 | Review HBEs; continuing progressing exposures as appropriate; modify activities and offer support as needed; plan HBEs | Parent meets separately with psychologist; review IFAM to discuss and normalize cognitive and emotional responses to adolescent in pain; review values-based goals; discuss strategies for increasing distress tolerance, promoting activity engagement and independence, and conveying confidence in adolescent |

| 7 | Graded Exposure with Behavioral Experiments-2 | Review HBEs; continuing progressing exposures as appropriate; modify activities and offer support as needed; plan HBEs | Parent observes adolescent exposure session, participating as appropriate. Psychology offers further explanation and rationale, as well as support to parent. Psychology provides feedback to parent about any naturally occurring responses to adolescent during exposure. |

| 8 | Graded Exposure with Behavioral Experiments-3 | Review HBEs; continuing progressing exposures as appropriate; modify activities and offer support as needed; plan HBEs | Parent meets separately with psychologist; discuss strategies for increasing distress tolerance, promoting activity engagement and independence, and conveying confidence in adolescent |

| 9 | Graded Exposure with Behavioral Experiments-4 | Review HBEs; continuing progressing exposures as appropriate; modify activities and offer support as needed; plan HBEs | Parent observes adolescent exposure session, participating as appropriate. |

| 10 | Graded Exposure with Behavioral Experiments-5 | Review HBEs; continuing progressing exposures as appropriate; modify activities and offer support as needed; plan HBEs | Parent meets separately with psychologist; discuss strategies for increasing distress tolerance, promoting activity engagement and independence, and conveying confidence in adolescent |

| 11 | Graded Exposure with Behavioral Experiments-6 | Review HBEs; continuing progressing exposures as appropriate; modify activities and offer support as needed; plan HBEs | Parent observes adolescent exposure session, participating as appropriate. |

| 12 | Relapse Prevention, Termination & Future Goals | Review HBEs; review general progress and accomplishments; discuss importance of relapse prevention and planning for future; target potential obstacles with Hot Seat cognitive-restructuring and problem-solving activity; assist adolescent in developing long-term goals; identify “lessons learned” throughout treatment; present graduation certificate. | Joint session: same content. |

The GET Living program was based on the following books and protocols: “Pain-related fear: exposure-based treatment for chronic pain” ([24]), “Multimodal CBT treatment for childhood OCD: a combined individual child and family treatment manual” [25], and “The ACT for teens program” [26].

2.7.1. Education and goal setting

The psychologist and physical therapist jointly deliver content to the patient and parent. Session 1–5 goals are to educate the patient and parent about the interpersonal fear avoidance model of pain (individual and interpersonal), present the treatment rationale and formulation, present ‘pain dilemma’ (the conceptualization of the dysfunctional behavioral strategies) [27], create values-based treatment goals to enhance motivation toward increased function vs. pain reduction, and create a pain-related fear activity list (‘activity ladder’) using the Photographs of Daily Activities-Youth in English (PHODA-YE) [28] to facilitate selection of individually tailored exposure targets and activities.

2.7.2. Graded exposure

As detailed in Table 1, physical therapists lead the exposures (sessions 6–11) that consist of engaging in activities perceived as potentially ‘harmful’ or ‘worrisome.’ Patients collaboratively select with the PT the exposure activity. Prior to beginning the activity, the patient completes the WILD scale assessing four relevant aspects of each task: 1) Willingness –patient's willingness to complete the task, 2) Importance – importance of the activity to the patient, 3) Likelihood of success – patient's assessment of likelihood of success in completing the activity, and 4) Difficulty – patient's assessment of the activity's level of difficulty. After completing the WILD scale, the patient generates an Exposure Action Plan (EAP) to potentially implement during the exposure activity if needed to maintain activity engagement when pain and distress may increase. EAP activities include strategies such as breathing, stretches, movement breaks, helpful thoughts (e.g., just get into it), and facilitators. Importantly, facilitators are not meant to be distractions. The patient attends to the activity at least in part to observe that the feared outcome either did not happen or was manageable (prediction error). Facilitators are activities that can coincide with the exposure activity to facilitate its completion – e.g., listening to music while working out. After each exposure activity, patients re-complete the WILD scale, discussing discrepancies between expectancies and experiences. Patients repeat, continue, and extend exposure activities outside of session (home-based exposures; HBEs) until competence in performing the activity increases across settings. HBEs can also be used to address activities that cannot be completed in session (e.g., riding public transportation, prolonged activities) and to address values-based goals as appropriate.

2.7.3. Parent component

Parents are integrally involved throughout treatment. In addition to attending and participating in sessions 1–5, parents observe some graded exposure sessions and provide encouragement in the execution of HBEs. During the other exposure sessions, parents meet individually with the psychologist. These sessions focus on education and parent behavior change. Module 1 focuses on parent distress in the context of their child's pain, expectations for treatment, and strategies to promote activity engagement. Module 2 emphasizes reacting vs. responding to child pain. Module 3 centers on child self-responsibility in treatment, the concept of rescuing vs. riding it out when the child is in distress, and addresses what messages are being sent with behavioral responses toward the child.

2.7.4. Wrap-up

Relapse prevention, long-term goal setting, and termination focuses on the maintenance and generalization of earlier treatment gains through problem solving. The patient and parent generate a ‘Top Lessons Learned’ during the final treatment session.

2.8. Multidisciplinary Pain Management [29,30] (see Table 2 for detailed treatment description)

Table 2.

Description of multidisciplinary pain management.

| Session | Topic | Adolescent Content | Parent Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rapport Building, History | Build rapport; obtain patient history. Discuss gals for treatment. | Joint Session: Same content |

| 2 | PT Session 1 | Child in Physical Therapy | N/A |

| 3 | Biopsychosocial Model Education | Biopsychosocial model of pain; gate control theory of pain; stress-pain connection | Joint Session: Same content |

| 4 | PT Session 2 | Child in Physical Therapy | N/A |

| 5 | Setting Treatment Goals | Discuss SMART goals; assist adolescent in completing goals. | N/A |

| 6 | PT Session 3 Treatment Goals (Parent only) |

Child in Physical Therapy | Parent meets separately with psychologist; Discuss SMART goals with the parent that focus on enhancing adolescent coping; assist parent in completing goals. |

| 7 | Coping Skills training | Learn and rehearse relaxation techniques (e.g., breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, imagery) | N/A |

| 8 | PT Session 4 Coping Skills Training 1 (Parent only) |

Child in Physical Therapy | Parent learns relaxation techniques (e.g., breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, imagery) being taught to the patient and how to encourage the patient to use these skills at home. |

| 9 | Cognitive Restructuring | Introduction to fundamental cognitive-behavioral strategies including active coping, distraction, and cognitive restructuring | N/A |

| 10 | PT Session 5 Coping Skills Training 2 (Parent Only) |

Child in Physical Therapy | Parent introduction to fundamental cognitive-behavioral strategies taught in the adolescent session including active coping, distraction, and cognitive restructuring |

| 11 | Relapse Prevention, Termination & Future Goals | Review accomplishments; assist adolescent in developing long-term goals; identify “lessons learned” throughout treatment; present graduation certificate. | Joint Session: Same content |

| 12 | PT Session 6 | Child in Physical Therapy | N/A |

2.8.1. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for pain management

CBT consists of six patient sessions and three parent-only sessions delivered by the psychologist. The initial CBT session is delivered jointly with the child and parent and focuses on psychoeducation on pain management. The next four child-only sessions focus on education about the biopsychosocial model and the gate control theory of pain, as well as goal setting, relaxation and coping skills training (including diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and guided imagery), and cognitive restructuring. The parent-only CBT sessions address setting goals, parent responses to their child's pain (identifying maladaptive responses and shifting to appropriate and adaptive responses), coping skills, and cognitive restructuring. The final CBT session is delivered jointly to the child and parent and focuses on relapse prevention, long term goals, and reviewing accomplishments made during treatment.

2.8.2. Physical therapy (PT) for pain management

PT consists of six sessions delivered by a licensed physical therapist. The initial PT session focuses on history-taking, conducting a standardized systems review, and using tests and measures to establish baselines for strength, range of motion, balance and proprioception, sensation, coordination, endurance, movement patterns, postural impairments, and pain. The remaining treatment sessions are based on the Guide to Physical Therapy Practice 3.0 and focus on establishing and monitoring of a home therapeutic exercise program, progressing activities and exercises as tolerated, the use of modalities (e.g., heat/ice) as appropriate, and providing patient and caregiver education. The final PT session focuses on maintenance and generalization of earlier treatment gains to prevent future complications, a review of accomplishments made during treatment, and recommendations for ongoing treatment.

2.9. Assessment of outcomes

All patient and parent surveys and daily diaries will be completed online through the secure, web-based application REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture). Patients and parents attend in-person baseline and discharge assessment visits, with 3- and 6-month follow-up completed online. Table 3 lists outcomes (primary, secondary, additional, SCED, exploratory, implementation) and covariates.

Table 3.

| Domains/Outcomes | Measure | Description of Measure | Respondent | Time point administered |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL | End | 3-m | 6-m | ||||

| Primary Outcomes | |||||||

| Pain-related Fear and Avoidance | Fear of Pain Questionnaire (FOPQ-C) | Assesses fear of pain (11 items) and avoidance of activities (13 items). | Adolescent | x | x | x | x |

| Photograph Series of Daily Activities (PHODA-YE) | 50-item measure of photographs of activities (activities of daily living, physical activities, social activities) where adolescents rate the worry and anticipated pain associated with each activity by dragging the photograph along a ‘thermometer’ ranging from 0 to 10. | Adolescent | x | x | x | x | |

| Secondary Outcome | |||||||

| Functional Disability | Functional Disability Inventory (FDI) | 15-item measure assessing perceived difficulty in performing activities in school, home, physical, and social contexts. | Adolescent | x | x | x | x |

| Additional Outcomes: Child | |||||||

| Pain | Numeric Rating Scale | Patients rate their “typical or usual pain” and “current pain” on a standard 11-point numeric rating scale (0 = “no pain” to 10 = “most pain possible”) | Adolescent | x | x | x | x |

| Pain Catastrophizing | Pain Catastrophizing Scale, Child version (PCS-C) | 13-item measure assessing negative cognitions associated with pain. | Adolescent | x | x | x | x |

| Pain Acceptance | Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire for Adolescents-8 (CPAQ-A8) | 8-item measure assessing pain acceptance in the adolescent. | Adolescent | x | x | x | x |

| School Functioning | Pediatric Quality of Life-School Functioning (PedsQL) | 5-item subscale of the PedsQL assessing school functioning, including school absences, ability to concentrate, and keeping up with assigned work. | Parent | x | x | x | x |

| Additional Outcomes: Parent | |||||||

| Psychological Flexibility | Parent Psychological Flexibility Questionnaire (PPFQ-10) | 10-item measure assessing parent ability to accept their distress and respond flexibly to their child's pain. | Parent | x | x | x | x |

| Pain Acceptance | Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire (PPAQ) | 15-item measure assessing parent acceptance of their child's pain. | Parent | x | x | x | x |

| Pain-related Fear and Avoidance | Parent Fear of Pain Questionnaire (PFOPQ) | 23-items assessing parent fear and avoidance behavior associated with their child's pain experiences. | x | x | x | x | |

| Pain Catastrophizing | Pain Catastrophizing Scale- Parent Version (PCS-P) | 13-item measure assessing parents' negative cognitions associated with their child's pain. | Parent | x | x | x | x |

| Protective Behaviors | Adult Responses to Children's Symptoms | 16-item subscale assessing parent protective behavioral responses to children's pain behaviors. | Parent | x | x | x | x |

| Miscarried Helping | Helping for Health Inventory | 15-items assessing miscarried helping in parents of children with chronic pain. | Parent | x | x | x | x |

| SCED Outcomes | |||||||

| Child Daily Diary | 16-items assessing fear, avoidance, activity engagement/acceptance, pain-related distress, functioning, pain, and sleep in the last 24 h+. | Adolescent | D | D | 7-days | 7-days | |

| Parent Daily Diary | 11-items assessing distress, protective behavior, activity encouragement/acceptance, and family impact in the last 24 h+. | Parent | D | D | 7-days | 7-days | |

| Exploratory Outcomes | |||||||

| Biomechanics | Participants complete a 6-min walk test, jogging trials, and a single and double limb squat task, drop jump task. | Adolescent | x | x | n/a | n/a | |

| Physical Activity | Actigraphy | Daily mean and peak activity are collected via an Actigraphy watch [49] | Adolescent | D | D | n/a | n/a |

| Healthcare Use and Cost | Cost Diaries | Cost diaries are completed on a weekly basis and assess health care service use, out of pocket costs, support provided from family, friends and professional carers. | Parent | W | W | x | x |

| Quality of life and utility | EuroQual 5-Dimension Heath-related Quality of Life for Youth (EQ-5D-Y) | 5-item measure assessing health-related quality of life comprised of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. | Parent | x | x | x | x |

| Covariates | |||||||

| Medical History | chronic pain history and course (e.g., pain onset, duration, intensity, location, course, and current medications) | Adolescent, Parent | x | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Demographics | age, sex, education level and school absences, family composition, parental employment, income and sick leave, and ethnic background | Adolescent, Parent | x | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Readiness to Change | Pain Stages of Change Questionnaire-short form (PSOCQ-A; PSOCQ-P) | 13-item measures assessing adolescent readiness to adopt a self-management approach to chronic pain and parent readiness to support this approach. | Adolescent, Parent | x | x | x | x |

| Depression | Children's Depression Inventory (CDI-2) | 28-item measure assessing youth depressive symptoms. | Adolescent | x | x | x | x |

| Anxiety | Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) | 50-item measure assessing anxiety in children and adolescents across four subscales: physical symptoms, social anxiety, harm avoidance, and separation anxiety. | Adolescent | x | x | x | x |

| Treatment Satisfaction | Pain Service Satisfaction Test (PSST) | 23-items assessing the patient and parent's experience with the intervention provided. | Adolescent, Parent | n/a | x | x | x |

| Treatment Expectancy | Treatment Expectancy and Creditability (TEC) | 6-items assessing expectations related to the effectiveness and benefits from the intervention received. | Adolescent, Parent | n/a | S1 | n/a | n/a |

| Treatment Adherence | daily diary completion, percentage of patients who drop out prior to treatment completion, and percentage of sessions completed on schedule. | Researcher | n/a | x | n/a | n/a | |

| Treatment Fidelity | Fidelity checklists for presence/absence of treatment elements and treatment process are coded for all sessions across treatment arms. | Researcher | n/a | x | n/a | n/a | |

Note. +Each word in bold is a separate construct assessed on the daily diary. BL = baseline; End = Discharge; D = Daily; W=Weekly, S = session.

2.9.1. Baseline assessment

Once eligibility is confirmed, patients and parent will be asked to attend an initial baseline study visit, which will occur at the Motion and Sports Performance Laboratory at Stanford Children's Health. Following consent and assent, patients and parent will complete baseline assessments, including a baseline biomechanical assessment, measuring gait at varying speeds, as well as self-report questionnaires. During this visit, patients will be given an Actigraph, which will monitor sleep and activity level through the trial. Patient and parent will also be introduced and oriented to the electronic Daily Diaries, which they will complete each day while enrolled in treatment. Following this baseline study visit, patients will undergo a pre-treatment data collection period (ranging from 10 to 21 days). The study biostatistician will create a randomization scheme to determine the number of days for the pre-treatment baseline period for each individual adolescent. During this time, patients will wear the Actigraph, and patients and parents will be asked to complete Daily Diaries.

2.9.2. Discharge assessment

Discharge assessment occurs after all treatment sessions are complete at the Motion and Sports Performance Laboratory at Stanford Children's Health. Assessment will consist of biomechanical motion analysis, self-report questionnaires, and an exit interview. Electronic daily diaries will conclude and patients will return the Actigraph watch at the discharge assessment.

2.9.3. Follow-up assessment

Follow-up assessment occurs at 3 and 6-months post-discharge. During the follow-up period, patients and parents will complete 7-days of daily diaries and the battery of self-report questionnaires online, no in-person visit is scheduled.

2.10. Primary outcome

2.10.1. Pain-related fear avoidance

Pain-related fear avoidance is the primary outcome for the GET Living trial. It will be measured by the Fear of Pain Questionnaire (FOPQ-C [4] and Photograph Series of Daily Activities-Youth English (PHODA-YE [28]). The FOPQ-C consists of 24 items, with each item rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree”). The FOPQ-C contains two subscales: Fear of Pain (11 items) and Avoidance of Activities (13 items). Total score is derived by summing items, with higher scores indicating greater pain related fear and avoidance of activities. The PHODA-YE is a 50-item electronic measure assessing worry associated with activities of daily living (13 items), exercise/sports activities (15 items), social/school activities (13 items), and upper extremity activities (9 items). To complete each item the patient is exposed to a photograph and label of the activity and asked to rate their worry “that this activity would be harmful to your pain” by dragging each photograph along a ‘worry thermometer’ ranging from 0 to 10. Each photograph is given a rating according to its position on the thermometer. Patients then rate their anticipated pain if they engaged in the activity. Mean perceived harm and anticipated pain scores (ranging from 0 to 10) is calculated as the sum of each rating divided by the total number of pictures.

2.11. Secondary outcome

2.11.1. Functional disability

Functional disability will be assessed using the Functional Disability Inventory (FDI [31]), a 15-item self-report measure of perceived difficulty in performing activities in school, home, physical, and social contexts. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no trouble) to 4 (impossible). Items are summed to create a total score, with higher scores indicating greater disability. The FDI is widely used in pediatric pain research and is recommended as the gold-standard measure of physical functioning for school age children and adolescents for clinical trials in pediatric chronic pain.

2.12. Additional outcomes: child

2.12.1. Pain

Patients will provide their pain rating on a standard Visual Analog Scale (VAS) equating to a range from 0 (“no pain”) to 10.0 (“most pain possible”) on a daily basis from baseline to end of treatment [32,33]. Average pain intensity ratings will be calculated for 7 days prior to the first treatment session (baseline average pain) and 7 days prior to the discharge assessment (discharge average pain).

2.12.2. Pain catastrophizing

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale -Child Version (PCS-C [34]) assesses negative cognitions associated with pain. The PCS-C is comprised of 13-items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “not at all true” to 4 “very true”). A total score is obtained by summing all items. Higher scores indicate higher levels of catastrophic thinking.

2.12.3. Pain acceptance

Patient report on the Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire for Adolescents-short form (CPAQ-A8 [35])will be used to assess pain acceptance in the child. The CPAQ-A8 is an 8-item measure consisting of two subscales: activity engagement (4 items) and pain willingness (4 items). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Never True) to 4 (Always True).

2.12.4. School functioning

The Pediatric Quality of Life-School Functioning subscale (PedsQL [36]) consists of 5 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “never” to 4 = “almost always”). Completed by the parent, higher scores equate with better school functioning.

2.13. Additional outcomes: parent

2.13.1. Parent psychological flexibility

The Parent Psychological Flexibility Questionnaire [37,38] (PPFQ-10 [39]) is a parent self-report questionnaire assessing a parent's ability to accept their own distress and respond adaptively and flexibly to their child's pain. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = “never true” to 6 = “always true”). Higher scores indicate greater parent psychological flexibility.

2.13.2. Parent pain acceptance

The Parent Pain Acceptance Questionnaire (PPAQ [40]) is used to assess parents' acceptance of their child's pain. The PPAQ contains 15-items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “never true” to 4 = “always true”) with two subscales: activity engagement and acceptance of pain-related thoughts and feelings. Higher scores indicate greater parent acceptance of child pain.

2.13.3. Parent pain-related fear and avoidance

The Parent Fear of Pain Questionnaire (PFOPQ [6]) assesses parent's fear associated with their child's pain experiences. The PFOPQ contains 23 items assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “strongly disagree” to 4 “strongly agree”). Items are summed to create a total score, with higher scores indicated greater parent fear of their child's pain.

2.13.4. Parent pain catastrophizing

Pain Catastrophizing Scale-Parent Version (PCS-P [41]) assesses parents' negative cognitions associated with their child's pain. It is comprised of 13 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “not true at all” to 4 = “very true”). A total score is derived by summing items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of catastrophic thinking.

2.13.5. Parent protective responses

Adult Responses to Children's Symptoms (ARCS [42]) assesses parents' behavioral responses to children's pain behaviors. The protect scale (13 items) will be utilized in this study. The Protect scale refers to protective parental behavior, such as giving the child special attention and limiting the child's normal activities and responsibilities. All items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “never” to 4 “always”), with higher scores indicating greater use of a particular type of response to their child's pain.

2.13.6. Parent miscarried helping

The Helping for Health Inventory (HHI [43]) is a 15-item questionnaire assessing miscarried helping (i.e., parental behaviors intended to be helpful, but inadvertently reinforce pain behaviors and functional decline) in parents of children with chronic pain. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “rarely” to 5 = “always”). Items are summed to create a total score, with higher scores indicating greater miscarried helping.

2.14. SCED outcomes

2.14.1. Child diary

The child daily survey consists of 16 items assessing pain and functioning in the last 24 h (see Table 4 for child diary items). Based on validated questionnaires administered in this study, 11 of the diary items were selected to assess the following constructs: worry/fear (2 items), avoidance (2 items), functioning (3 items), activity engagement/acceptance (2 items), and pain reactivity (2 items). These 11 items are rated on a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The first 11 items are administered in a random order each day to mitigate habitual responses. Item 12 assesses current pain on a numeric rating scale (NRS), 0=“no pain” to 10=“worst pain possible”). Item 13 includes an open text box to describe anything exciting or stressful from the past 24 h. The final three questions assess sleep (e.g., bedtime, wake time, and quality of sleep rating). Patients receive a text message daily with a hyperlink to complete their daily diary.

Table 4.

Child daily diary items.

| Worry/Fear |

| I spent a lot of time worrying about my pain. |

| I was scared to do things that might hurt my body. |

| Avoidance |

| I skipped activities because of my pain. |

| I did not make any plans because of my pain. |

| Functioning |

| I was less active than usual because of my pain. |

| It was difficult to focus or concentrate because of my pain. |

| It was difficult to spend time with friends because of my pain. |

| Activity Engagement/Acceptance |

| I did the things I had to do while having pain. |

| I did things that were fun or important to me even though I had pain. |

| Pain Reactivity |

| I had pain, but it did not bother me. |

| I felt sad or frustrated because of my pain. |

| Pain |

| On a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain), tell us how much pain you are feeling right now. |

| Stress |

| Please make note of anything exciting or stressful that happened today. |

| Sleep |

| What time did you get into bed last night? |

| What time did you get out of bed this morning? |

| On a scale of 0 (extremely poor) to 10 (extremely good), how well did you sleep last night? |

2.14.2. Parent diary

The parent daily survey consists of 11 total items to assess distress and behaviors in the last 24 h (see Table 5 for parent diary items). Nine items were based on validated questionnaires administered in this study and include: distress (3 items), protective behaviors (2 items), impact of pain on family (2 items), and acceptance/activity encouragement (2 items). These 9 items are rated on a visual analog scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The first 9 items are administered in a random order each day. Item 10 includes an open text box to describe anything exciting or stressful from the past 24 h. The final item asks parents to rate their current distress on an NRS (0 = “no distress” to 10 = “severe distress”). Parents receive a text message daily with a hyperlink to complete their daily diary.

Table 5.

Parent daily diary items.

| Activity Engagement/Acceptance |

| I encouraged my child to do things that were fun or important to them regardless of their pain. |

| I encouraged my child to do the things they had to do regardless of their pain. |

| Protective Parent Behavior |

| I allowed my child to skip activities due to their pain. |

| I let my child sleep more than usual due to their pain. |

| Family Impact |

| I spent more time than usual with my child due to their pain. |

| Plans were changed due to my child's pain. |

| Distress |

| I felt I couldn't help my child when they were in pain. |

| I found it difficult to tolerate my child's suffering. |

| My child's pain was overwhelming to me. |

| Stress |

| Please make note of anything exciting or stressful that happened today. |

| On a scale of 0 (no distress) to 10 (severe distress), tell us how much distress you are feeling right now. |

2.15. Exploratory outcomes

2.15.1. Biomechanics

Body joint kinematic (motion) and kinetic (force) data will be collected with a 22-camera Vicon system (Centennial, CO, USA) with 5 integrated force plates (Bertec; AMTI). Markers will be placed on each adolescent according to the 3D Plug In Gait model (Vicon) with data recorded and processed in Nexus 2.6.1. Adolescents will walk, jog, complete a double and single leg squat, and drop jump task [[44], [45], [46]]. Ratings of anticipated and experienced pain and harm will be collected. Biomechanical variables including speed, step length, step width, peak hip and knee extensor moments, peak ankle plantar flexor moment, and sagittal and frontal plane kinematics of the hip and knee joints will be extracted using Polygon 4.3.3 (Vicon). For the 6-min Walk Test, the objective is to have the patient walk as far as possible in a self-paced manner for 6 min to provide an assessment of physical function. Patients walk back and forth around two cones, 8 m apart, with one lap demonstrated. The experimenter tracks the number of laps and calculates the overall distance walked [47,48].

2.15.2. Physical activity

Daily mean and peak activity via Actigraphy [49] will be collected during the 10–21 day randomized baseline period and throughout active treatment.

2.15.3. Healthcare use and cost

Health care service use, personal costs, support provided from family, friends and professional carers, and cost are completed by parents at baseline and on a weekly basis from baseline to end of treatment and once at each follow-up point. Parents report on children's health care service use (including general and specialist medical practitioners, physical therapists, alternative health care practitioners, medications, hospital admissions, out of pocket costs) and other impacts on children and parental activity (including athletic extracurricular activities, and parental days off work and sick leave) [50].

2.15.4. Quality of life and utility

EQ-5D-Y [51,52] is a standardized measure of health-related quality of life comprising five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. It includes the EQ VAS that records the patient's self-rated health on a vertical visual analogue scale. The scores can be converted to a single summary index number (utility) reflecting preferability compared to other health profiles.

2.16. Covariates

2.16.1. Medical history

Variables related to chronic pain including pain onset, duration, and intensity of pain symptoms, as well as course, and medications, will be collected.

2.16.2. Demographics

Demographic variables, including age, sex, educational level, family composition, parental labor force status, hours of work, income, job loss, and ethnic background, will be assessed via patient and parent report at baseline.

2.16.3. Readiness to change

Pain Stages of Change Questionnaire, Adolescent and Parent report (PSOCQ-A; PSOCQ-P [53]) short forms are 13-item versions that assess patient self-report of readiness to adopt a self-management approach to chronic pain and parent reports of their mindset regarding motivation to change with respect to their adolescents current behavior. Both the adolescent self-report and the parent-are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”).

2.16.4. Depression

Symptoms of depression will be assessed using the Children's Depression Inventory-2 (CDI-2 [54]). The CDI-2 is a 28-item self-report measures of youth depressive symptoms. Higher scores indicate greater depressive symptoms.

2.16.5. Anxiety

Anxiety symptoms will be assessed using the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children-2 (MASC-2 [55])a 50-item self-report scale assessing anxiety in children and adolescents. Higher scores indicate greater anxiety symptoms.

2.17. Implementation outcomes

2.17.1. Treatment satisfaction

Treatment satisfaction at the end of treatment will be evaluated by examining mean satisfaction scores on an adapted version of the Pain Service Satisfaction Test (PSST [56]). The PSST consists of 22 items and assesses the patient and parent's experience of pain clinic services. The items were tailored to the intervention.

2.17.2. Treatment expectancy

Treatment acceptability will be measured by the Treatment Expectancy and Creditability measure (TEC-C, TEC-P [57]). The TEC is comprised of 6 items assessing expectations related to the effectiveness of the current treatment. The TEC is completed by the patient (TEC-C) and the parent (TEC-P) at the end of the first treatment session in both arms.

2.17.3. Treatment adherence

Adherence and retention will be assessed by examining parent and patient adherence to daily diary completion, percent of patients who drop out prior to treatment completion, and percentage of sessions completed on schedule.

2.17.4. Treatment fidelity

Treatment elements for each arm have been labeled into one of five categories (essential and unique, essential but not unique, unique but not essential, compatible, prohibited) [58]. A trained research assistant will listen to audio/video recordings of treatment sessions and complete treatment fidelity checklists for presence/absence of treatment elements and treatment process, for both parents and child sessions across treatment arms.

2.18. Data analysis

The study biostatistician will conduct all analyses. Covariates (age, pain variables, gender, diagnosis, readiness to change, anxiety, depression) will be examined for the primary, secondary, additional, and exploratory outcomes.

2.18.1. Primary, secondary, and additional outcomes

Linear mixed effects models will be used to compare GET Living to MPM across all non-SCED outcomes. We will model our outcomes at four time points using a mixed effects linear model with fixed effects for treatment assignment, time period, the interaction between treatment and time period, and baseline covariates and a random effect for individual. The random effect will allow us to account for the correlation in the outcome within individual over time.

2.18.2. Exploratory outcomes

To examine biomechanical data, biomechanical variables will be extracted using Polygon 4.3.3 (Vicon) for error free data reduction. Variables extracted include speed, step length, step width, peak hip and knee extensor moments, peak ankle plantar-flexor moment, and peak sagittal and frontal plane kinematics of the hip and knee joints. We will model biomechanical variables using mixed 2 (time) x 2 (group) ANOVAs. If biomechanical variables differ by pain site (upper, trunk, lower, diffuse) this will be included as a covariate. To examine Actigraphy data, Actilife software will be used to extract data and calculate mean and peak daily activity. Published data reduction methods will be used [49]. We will model physical activity (mean, peak) at two time points using mixed 2 (time) x 2 (group) ANOVAs. Rate of change in physical activity from baseline to discharge will also be examined using the randomization tests used for SCED outcomes, described below. To examine healthcare cost data, we will model healthcare cost variables using t-tests and linear and mixed regression models.

2.18.3. Implementation outcomes

Mean satisfaction scores will be examined. Additionally, mean parent and adolescent adherence to daily diary completion, percent of patient dropout prior to treatment completion, and percent of sessions completed on-schedule will also be examined.

2.18.4. SCED outcomes

The data obtained from the randomized single-case experimental phase design used in this study have a hierarchical two-level structure with observations (level 1) nested within patients (level 2). This nested structure induces dependency within the data: observations vary not only due to random sampling within a patient, but also between different patients. For analysis of the data, we will use a hierarchical linear model, allowing us to combine all patients’ data into one single multilevel model while also taking account both the within- and between-patient dependencies [59,60]. The within- and between-patient variability will be modeled, as well as the overall effects of the treatment across patients. For conducting the multilevel analysis and for obtaining inference results in R [61], MultiSCED will be used (http://52.14.146.253/MultiSCED/) [62]. This daily individual data also allows for use of randomizations tests (https://tamalkd.shinyapps.io/scda/) [63] to assess the difference between baseline to discharge and baseline to 3 and 6-month follow-up on Daily Dairies [16,64].

2.19. Sample size and power analysis

The largest feasible sample size was chosen to obtain as precise estimates as possible of improvement in adolescent disability while also ensuring adequate power for the treatment difference in the improvement in adolescent pain-related fear avoidance. In our primary power calculation, we assumed that the improvement in adolescent pain-related fear avoidance at 3-months would be 21.5 in Get Living and 5 in MPM, a difference of 16.5, with a standard deviation for change of 18.8 derived from our prior work [65]. Under this scenario we will have power of 91% with 58 (29 in each arm) at end of study. Under more conservative assumptions, we still have power of 87% with this treatment difference but only 52 at the end of study, and power of 81% with a smaller treatment difference of 15.5 and 50 at end of study. This resulted in a total sample size of 74 (n = 37 for each treatment arm). A recent introceptive exposure treatment for youth with chronic pain observed a medium effect size (cohen's d = 0.73) improvement in pain-related fear, suggesting a sample size of 31 per group to achieve 80% power, suitably within range of these estimates [66]. Based on pilot data (GET Living: NCT01974791; in revision), roughly 19% attrition is expected during treatment, resulting in a total of 60 adolescents at discharge. Further attrition to N = 58 is expected at the end of follow-up (6-months post discharge from the study). Power calculations were first performed using paired t-tests to assess the change from baseline to 3 and 6-months. Means and standard deviations of observed changes in pilot data were also examined. Data was then simulated from the analytic model using the standard deviations at each time point and standard deviations of change to calculate correlation, and the random effect and error variance. The mixed model simulation allowed the use of more data and yielded slightly higher power estimates.

2.20. Monitoring

The GET Living RCT will be monitored by KAI, the executive secretary of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS). A Safety Monitoring Committee (SMC) of three experts, approved by the NIAMS, will meet quarterly to review overall subject enrollment status, accrual, adherence, protocol deviations and adverse events.

2.21. Trial status

GET Living was prospectively registered on ClinicalTrials.gov with the U.S. National Library of Medicine on 10/08/2018 (NCT03699007). Participant recruitment began in January 2019 and is expected to complete in December 2020, with data collection ceasing approximately 9 months later.

2.22. Discussion

Effective treatment for chronic pain likely requires focusing on mechanisms that perpetuate the persistent pain state, rather than treating all patients with chronic pain as ‘the same’ [67]. Based on an empirically validated theoretical model with rigorous experimental evidence [68,69] graded in-vivo exposure has emerged as a promising treatment for patients struggling with chronic pain and fear avoidance. This RCT represents the first study to directly compare multidisciplinary pain management to graded in-vivo exposure in adolescents with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Moreover, this RCT is enhanced with a single case experimental design (SCED) framework in order to answer clinically relevant questions regarding what works better for whom and when these changes occur over the course of treatment.

Providing a framework where multidisciplinary RCTs can be rigorously combined with SCEDs represents a critical step forward in the field and will enable an investigation of group differences in terms of efficacy and individual response patterns. The results of this trial are expected to provide a model for future studies to adopt this research and statistical design and well as provide substantive findings regarding the effectiveness of graded in-vivo exposure for youth with chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Acknowledgements

This investigation was supported by NIAMS/R21AR072921 awarded to LES. There are no conflicts of interest to report. We thank Dr Rupendra Shrestha from Macquarie University for his advice on statistical methods related to economic analysis.

References

- 1.Huguet A., Miro J. The severity of chronic pediatric pain: an epidemiological study. J. Pain. 2008;9:226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simons L.E., Kaczynski K.J. The Fear Avoidance model of chronic pain: examination for pediatric application. J. Pain. 2012;13:827–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simons L.E., Kaczynski K.J., Conroy C., Logan D.E. Fear of pain in the context of intensive pain rehabilitation among children and adolescents with neuropathic pain: associations with treatment response. J. Pain. 2012;13:1151–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simons L.E., Sieberg C.B., Carpino E., Logan D., Berde C. The Fear of Pain Questionnaire (FOPQ): assessment of pain-related fear among children and adolescents with chronic pain. J. Pain. 2011;12:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goubert L., Simons L.E. Cognitive styles and processes in paediatric pain. Oxford Textbook of Pediatric Pain. 2013:95–101. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simons L.E., Smith A., Kaczynski K., Basch M. Living in fear of your child's pain: the Parent Fear of Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 2015;156:694–702. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sieberg C.B., Williams S., Simons L.E. Do parent protective responses mediate the relation between parent distress and child functional disability among children with chronic pain? J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2011;36:1043–1051. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow E.T., Otis J.D., Simons L.E. The longitudinal impact of parent distress and behavior on functional outcomes among youth with chronic pain. J. Pain. 2016;17:729–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hechler T., Dobe M., Kosfelder J. Effectiveness of a 3-week multimodal inpatient pain treatment for adolescents suffering from chronic pain: statistical and clinical significance. Clin. J. Pain. 2009;25:156–166. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318185c1c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams A.C., Eccleston C., Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;11:CD007407. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eccleston C., Palermo T.M., Williams A.C. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014:CD003968. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003968.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palermo T.M., Eccleston C., Lewandowski A.S., Williams A.C., Morley S. Randomized controlled trials of psychological therapies for management of chronic pain in children and adolescents: an updated meta-analytic review. Pain. 2010;148:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leeuw M., Goossens M.E., van Breukelen G.J. Exposure in vivo versus operant graded activity in chronic low back pain patients: results of a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2008;138:192–207. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linton S.J., Boersma K., Jansson M., Overmeer T., Lindblom K., Vlaeyen J.W. A randomized controlled trial of exposure in vivo for patients with spinal pain reporting fear of work-related activities. Eur. J. Pain. 2008;12:722–730. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Jong J.R., Vlaeyen J.W., van Eijsden M., Loo C., Onghena P. Reduction of pain-related fear and increased function and participation in work-related upper extremity pain (WRUEP): effects of exposure in vivo. Pain. 2012;153:2109–2118. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vlaeyen J.W., De Jong J.R., Onghena P., Kerckhoffs-Hanssen M., Kole-Snijders A.M. Can pain-related fear be reduced? The application of cognitive-behavioural exposure in vivo. Pain Res. Manag. 2002;7:144–153. doi: 10.1155/2002/493463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dekker C., Goossens M.E., Bastiaenen C.H., Verbunt J.A. Study protocol for a multicentre randomized controlled trial on effectiveness of an outpatient multimodal rehabilitation program for adolescents with chronic musculoskeletal pain (2B Active) BMC Muscoskelet. Disord. 2016;17:317. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1178-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simons L.E. Fear of pain in children and adolescents with neuropathic pain and complex regional pain syndrome. Pain. 2016;157(Suppl 1):S90–S97. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clinch J., Eccleston C. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in children: assessment and management. Rheumatology. 2009;48:466–474. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kashikar-Zuck S., Flowers S.R., Claar R.L. Clinical utility and validity of the Functional Disability Inventory among a multicenter sample of youth with chronic pain. Pain. 2011;152:1600–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kent D.M., Rothwell P.M., Ioannidis J.P., Altman D.G., Hayward R.A. Assessing and reporting heterogeneity in treatment effects in clinical trials: a proposal. Trials. 2010;11:85. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lillie E.O., Patay B., Diamant J., Issell B., Topol E.J., Schork N.J. The n-of-1 clinical trial: the ultimate strategy for individualizing medicine? Per Med. 2011;8:161–173. doi: 10.2217/pme.11.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davidson K.W., Peacock J., Kronish I.M., Edmondson D. Personalizing behavioral interventions through single-patient (N-of-1) trials. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2014;8:408–421. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vlaeyen J., Morley S., Linton S.J., Boersma K., de Jong J. IASP press; 2012. Pain-related Fear: Exposure Based Treatment for Chronic Pain. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piacentini J, Langley, A., Roblek, T., Chang, S., & Bergman, R. L. Multimodal CBT Treatment for Childhood OCD: a Combined Individual Child and Family Treatment Manual. (unpublished)..

- 26.Greco L. The ACT for Teens Program (Unpublished)..

- 27.W R.K. Values-based exposure and acceptance in the treatment of pediatric chronic pain: from symptom reduction to valued living. Pediatric Pain Letter. 2007;9 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simons L.E., Pielech M., McAvoy S. Photographs of Daily Activities-Youth English: validating a targeted assessment of worry and anticipated pain. Pain. 2017;158:912–921. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Logan D.E., Simons L.E. Development of a group intervention to improve school functioning in adolescents with chronic pain and depressive symptoms: a study of feasibility and preliminary efficacy. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010;35:823–836. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palermo T.M. Oxford Press; New York, NY: 2012. Cognitive Behaioral Therapy for Chronic Pain in Children and Adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker L.S., Greene J.W. The functional disability inventory: measuring a neglected dimension of child health status. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 1991;16:39–58. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/16.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birnie K.A., Hundert A.S., Lalloo C., Nguyen C., Stinson J.N. Recommendations for selection of self-report pain intensity measures in children and adolescents: a systematic review and quality assessment of measurement properties. Pain. 2019;160:5–18. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Baeyer C.L., Spagrud L.J., McCormick J.C., Choo E., Neville K., Connelly M.A. Three new datasets supporting use of the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS-11) for children's self-reports of pain intensity. Pain. 2009;143:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crombez G., Bijttebier P., Eccleston C., Mascagni T., Mertens G., Goubert L., Verstraeten K. The child version of the pain catastrophizing scale (PCS-C): a preliminary validation. Pain. 2003;104:639–646. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gauntlett-Gilbert J., Alamire B., Duggan G.B. Pain acceptance in adolescents: development of a short form of the CPAQ-A. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018:453–462. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsy090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varni J.W., Seid M., Kurtin P.S. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med. Care. 2001;39:800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCracken L.M., Gauntlett-Gilbert J. Role of psychological flexibility in parents of adolescents with chronic pain: development of a measure and preliminary correlation analyses. Pain. 2011;152:780–785. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallace D.P., McCracken L.M., Weiss K.E., Harbeck-Weber C. The role of parent psychological flexibility in relation to adolescent chronic pain: further instrument development. J. Pain. 2015;16:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Timmers I., Simons L.E., Hernandez J.M., McCracken L.M., Wicksell R.K., Wallace D.P. Parent psychological flexibility in the context of pediatric pain: brief assessment and associations with parent behavior and child functioning. Eur. J. Pain. 2019:1340–1350. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith A.M., Sieberg C.B., Odell S., Randall E., Simons L.E. Living life with My child's pain: the parent pain acceptance questionnaire (PPAQ) Clin. J. Pain. 2015;31:633–641. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goubert L., Eccleston C., Vervoort T., Jordan A., Crombez G. Parental catastrophizing about their child's pain: the parent version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PSC-P): a preliminary validation. Pain. 2006;123:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Claar R.L., Guite J.W., Kaczynski K.J., Logan D.E. Factor structure of the Adult Responses to Children's Symptoms: validation in children and adolescents with diverse chronic pain conditions. Clin. J. Pain. 2010;26:410–417. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181cf5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fales J.L., Essner B.S., Harris M.A., Palermo T.M. When helping hurts: miscarried helping in families of youth with chronic pain. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014;39:427–437. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sil S., Thomas S., DiCesare C. Preliminary evidence of altered biomechanics in adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67:102–111. doi: 10.1002/acr.22450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tran S.T., Thomas S., DiCesare C. A pilot study of biomechanical assessment before and after an integrative training program for adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016;14:43. doi: 10.1186/s12969-016-0103-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glaviano N.R., Saliba S. Association of altered frontal plane kinematics and physical activity levels in females with patellofemoral pain. Gait Posture. 2018;65:86–88. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.07.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brooks D., Solway S., Gibbons W.J. ATS statement on six-minute walk test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;167:1287. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.167.9.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li A.M., Yin J., Yu C.C. The six-minute walk test in healthy children: reliability and validity. Eur. Respir. J. 2005;25:1057–1060. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00134904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson A.C., Palermo T.M. Physical activity and function in adolescents with chronic pain: a controlled study using actigraphy. J. Pain. 2012;13:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goossens M.E., Rutten-van Molken M.P., Vlaeyen J.W., van der Linden S.M. The cost diary: a method to measure direct and indirect costs in cost-effectiveness research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2000;53:688–695. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wille N., Badia X., Bonsel G. Development of the EQ-5D-Y: a child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual. Life Res. 2010;19:875–886. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9648-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ravens-Sieberer U., Wille N., Badia X. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of the EQ-5D-Y: results from a multinational study. Qual. Life Res. 2010;19:887–897. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9649-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guite J.W., Logan D.E., Simons L.E., Blood E.A., Kerns R.D. Readiness to change in pediatric chronic pain: initial validation of adolescent and parent versions of the Pain Stages of Change Questionnaire. Pain. 2011;152:2301–2311. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kovacs M. The children's depression inventory-second edition (CDI-2) Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1992;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.March J., Parker J.D., Sullivan K., Stallings P., Conners C.K. The multidimensional Anxiety Scale of Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCracken L.M., Klock P.A., Mingay D.J., Asbury J.K., Sinclair D.M. Assessment of satisfaction with treatment for chronic pain. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 1997;14:292–299. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(97)00225-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Borkovec T.D., Nau S.D. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychol. 1972;3:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leeuw M., Goossens M.E., de Vet H.C., Vlaeyen J.W. The fidelity of treatment delivery can be assessed in treatment outcome studies: a successful illustration from behavioral medicine. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009;62:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Den Noortgate W., Onghena P. Multilevel Meta-analysis: a comparison with traditional meta-analytical procedures. Educational and Psychology Measturement. 2003;63:765–790. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Den Noortgate W., Onghena P. A multilevel meta-analysis of single-subject experimental design studies. Evidence-Based Commun. Assess. Interv. 2008;2:142–151. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Team R.R. Development core team. RA Lang Environ Stat Comput. 2013;55:275–286. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Declercq L., Cools W., Beretvas S.N., Moeyaert M., Ferron J.M., Van den Noortgate W. MultiSCED: a tool for (meta-)analyzing single-case experimental data with multilevel modeling. Behav. Res. Methods. 2019:1–16. doi: 10.3758/s13428-019-01216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bulte I., Onghena P. The single case data analysis package: analysing single-case experiments with R software. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods. 2013;12:450–478. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Onghena P., Edgington E.S. Customization of pain treatments: single-case design and analysis. Clin. J. Pain. 2005;21:56–68. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00007. discussion 9-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simons L.E., Sieberg C.B., Pielech M., Conroy C., Logan D.E. What does it take? Comparing intensive rehabilitation to outpatient treatment for children with significant pain-related disability. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013;38:213–223. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Flack F., Stahlschmidt L., Dobe M. Efficacy of adding interoceptive exposure to intensive interdisciplinary treatment for adolescents with chronic pain: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2018;159:2223–2233. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simons L.E., Sieberg C.B., Coakley R.M. Patients with pain are not all the same: considering fear of pain and other individual factors in treatment. Pain Manag. 2013;3:87–89. doi: 10.2217/pmt.12.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meulders A., Vlaeyen J.W. Reduction of fear of movement-related pain and pain-related anxiety: an associative learning approach using a voluntary movement paradigm. Pain. 2012;153:1504–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vlaeyen J.W., Crombez G., Linton S.J. The fear-avoidance model of pain. Pain. 2016;157:1588–1589. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]