Abstract

Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells develop from CD4+CD8+ double-positive (DP) thymocytes and express an invariant Vα14–Jα18 T-cell receptor (TCR) α-chain. Generation of these cells requires the prolonged survival of DP thymocytes to allow for Vα14–Jα18 gene rearrangements and strong TCR signaling to induce the expression of the iNKT lineage-specific transcription factor PLZF. Here, we report that the transcription factor Yin Yang 1 (YY1) is essential for iNKT cell formation. Thymocytes lacking YY1 displayed a block in iNKT cell development at the earliest progenitor stage. YY1-deficient thymocytes underwent normal Vα14–Jα18 gene rearrangements, but exhibited impaired cell survival. Deletion of the apoptotic protein BIM failed to rescue the defect in iNKT cell generation. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and deep-sequencing experiments demonstrated that YY1 directly binds and activates the promoter of the Plzf gene. Thus, YY1 plays essential roles in iNKT cell development by coordinately regulating cell survival and PLZF expression.

Keywords: NKT cell, PLZF, YY1, Zbtb16

Introduction

Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells are a subset of αβ T cells characterized by the expression of a limited set of T-cell receptor (TCR) β-chains in association with an invariant TCR α-chain, such as Vα14–Jα18 in mice and Vα24–Jα18 in humans.1–4 These TCRαβ combinations endow iNKT cells with the ability to recognize glycolipid antigens, such as α-galactosylceramide, that are presented by the major histocompatibility complex class I, such as CD1d.5 These glycolipids can be derived from pathogens or from the host, and their activation of iNKT cells rapidly induces cytokine production that can modulate both innate and adaptive immune responses involved with infection, tumor surveillance, and autoimmunity.5

iNKT cells develop in the thymus from bone marrow precursors and diverge from conventional T-cell development at the CD4+CD8+ double-positive (DP) stage. After the successful rearrangement of the TCR gene loci, DP thymocytes receive priming signals triggered by the TCR recognition of CD1d–glycolipid complexes, causing the DP thymocytes to differentiate into immature CD24+ iNKT cells (stage 0). The immature precursors then give rise to the more mature CD24−CD44−NK1.1− cells (stage 1), which further develop into CD24−CD44+NK1.1− cells (stage 2) and finally into CD24−CD44+NK1.1+ mature iNKT cells (stage 3).5, 6

Many transcription factors and cofactors have been shown to regulate the distinct stages of iNKT cell differentiation. The earliest stage of iNKT cell development absolutely requires the transcription factors RORγt,7 c-Myb,8 PAXIP1,9 and HEB10 to support the prolonged survival of DP thymocytes and/or the rearrangement of the Vα–Jα segments to generate the iNKT cell characteristic of Vα14–Jα18 TCR. Runx1 also regulates iNKT cell differentiation at an early stage, independent of TCR gene rearrangements.11 Notably, the promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF) protein, encoded by the Zbtb16 gene, is the signature transcription factor of the iNKT cell lineage and directs the iNKT cell effector program.12, 13 In addition, Egr2 has also been shown to be required for iNKT cell generation by regulating cell proliferation and survival. More importantly, Egr2, induced by TCR signaling, directly binds and activates the Plzf promoter.14, 15 Other transcription factors that contribute to iNKT cell development include c-Myc,16, 17 Ets-1,18 T-bet,19 Id2,20 Hobit,21 Gata-3,22 Mef,23 and nuclear factor-κB.24

Yin Yang 1 (YY1) is a widely expressed transcriptional factor belonging to the GLI-Krüppel class of zinc finger proteins.25–28 As a transcriptional regulator, YY1 binds DNA through the recognition of a specific consensus sequence to activate or repress gene expression. YY1 plays important roles in cell growth, apoptosis, and cancer progression. Although the role of YY1 in many biological processes has been studied extensively, the effect of YY1 on the development and function of immune cells has not been fully investigated. A previous study showed that YY1 regulates VDJ gene rearrangements in the immunoglobulin heavy-chain (IgH) locus and is essential for B-cell development.29, 30 In addition, YY1 has been shown to play a critical role in germinal center B-cell differentiation.31–33 These studies highlighted the importance of YY1 in B-cell development and antibody response.

However, not much is known about the roles of YY1 in other immune cells. Several recent reports showed that YY1 played a role in the differentiation of T-helper 2,34 CD8+,35 and T-regulatory cells,36, 37 and that YY1 activity may be modulated by Src family tyrosine kinases.38 In particular, a role for YY1 in iNKT cell development has not been described. Here, using mice in which YY1 was conditionally deleted in T cells, we demonstrated that YY1 is absolutely required for iNKT cell development by regulating thymocyte survival as well as the expression of the lineage-specific transcription factor PLZF.

Materials and methods

Mice

Yy1f/f (014649), Cd4Cre/+ (022071), C57BL/6 (CD45.1+) (002014), Vα14-Tg (014639), and Bim–/– (004525) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. All mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment at the A*STAR Biological Resource Center. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations of the Biological Resource Center and Bioprocessing Technology Institute.

Flow cytometry

PBS57-loaded CD1d tetramers were obtained from the US National Institutes of Health Tetramer Core Facility. The following fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies were obtained from BioLegend: anti-CD45.1 (A20); anti-CD45.2 (104); anti-CD69 (H1.2F3); anti-NK1.1 (PK136); and anti-CD44 (IM7). Other fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences: anti-CD4 (GK1.5); anti-CD1d (1B1); anti-CD8 (53-6.7); anti-TCRβ (H57-597); and anti-CD24 (M1/69).

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from the thymus, spleen, and liver. Liver mononuclear cells were purified with a 40–70% Percoll gradient (Amersham Biosciences). Cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies, and samples were analyzed on an LSR II (Becton Dickinson) or were sorted with a FACSAria II (Becton Dickinson) flow cytometer. For the intracellular staining of PLZF and Egr2 expression, cells were processed with a Foxp3 fixation/permeabilization kit (eBioscience) and stained with a phycoerythrin-conjugated monoclonal anti-PLZF antibody (BioLegend, 9E12) or an allophycocyanin-conjugated monoclonal anti-Egr2 (eBioscience, erongr2) antibody.

Quantitative real-time PCR analyses

RNA was isolated from total or fluorscence-activated cell sorting-sorted thymocytes (CD4+, CD8+, CD4−CD8−, CD4+CD8+, CD1d-tet+CD24+, CD1d-tet+CD24−CD44−NK1.1−, CD1d-tet+CD24−CD44+NK1.1−, or CD1d-tet+CD24−CD44+NK1.1+) with TRIzol (Invitrogen) reagent, followed by reverse transcription using the RevertAid First strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Platinum SYBR Green Supermix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for quantitative PCR. The primer sequences were as follows: Yy1 forward, 5′-CCGGGGAATAAGAAGTGGGA-3′, reverse, 5′-TGATCTGCTCTTCAACCACTGTT-3′; Plzf forward, 5′-CCCAGTTCTCAAAGGAGGATG-3′, reverse, 5′-TTCCCACACAGCAGACAGAAG-3′; and β-actin forward, 5′-CGTGAAAAGATGACCCAGATCA-3′, reverse, 5′-CACAGCCTGGATGGCTACGT-3′.

Generation of mixed-bone marrow chimeras

Bone marrow chimeras were generated as previously described.39 Briefly, C57BL/6 (CD45.1+) mice at 6–8 weeks of age were irradiated with 900 rads from a cesium source. Six hours after the irradiation, a 1:1 mixture of Yy1f/fCd4Cre/+ (CD45.2+) or wild-type (WT) (CD45.2+) bone marrow cells with C57BL/6 (CD45.1+ or CD45.1+CD45.2+) bone marrow cells (total 3 × 106 cells) was injected intravenously into the recipient mice. The mice were analyzed 8 weeks after the bone marrow reconstitution.

Analyses of 5-bromodeoxyuridine incorporation and apoptosis

Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 2 mg of 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma-Aldrich) in 200 µL of phosphate-buffered saline and killed 20 h later for the examination of cell proliferation. Cell samples were labeled for surface antigens and then fixed and stained using the BrdU Detection Kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For detection of apoptosis, thymocytes were cultured in RPMI medium at 37 °C for 20 h and then labeled for surface antigens and stained using the FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences).

Analyses of Vα–Jα rearrangements

After the CD69−TCRβintCD4+CD8+ thymocytes were sorted, RNA was extracted and cDNA was generated as described above. The cDNA template was serially diluted at a ratio of 1:2, and transcripts were amplified and separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The primer sequences were as follows: Cα forward, 5′-TTCAAAGAGACCAACGCCAC-3′, reverse, 5′-TTCAGCAGGAGGATTCGGAG-3′; Vα3, 5′-GTCTTCGAAGGAGACTCGGTG-3′; Vα6, 5′-CTGCCTCATGTCAGCCTGAGAG-3′; Vα8, 5′-TGTGATGCTGAACTGCACCT-3′; Vα14, 5′-ACTGCGTCCTTCAATGTAATT-3′; Vα19, 5′-CCGCTCGAATGGGTACAGTT-3′; Jα2, 5′-ACCACTTAGTCCTCCAGTATTC-3′; Jα5, 5′-AGTGAGCTGCCCCACAAC-3′; Jα9, 5′-CCCGAAGGTAAGTTTGTAGCC-3′; Jα16, 5′-CAGCTTCTGGCCACTTGAA-3′; Jα18, 5′-CCCTAAGGCTGAACCTCTATC-3′; Jα30, 5′-AGATGTGTCCCTTTTCCAAAGATG-3′; and Jα56, 5′-TCAAAACGTACCTGGTATAACACTCAGAAC-3′.

Luciferase reporter assays

The mouse Yy1 gene was cloned into the murine stem cell virus retroviral vector. The proximal promoter of the mouse Plzf (positions −420 to +138) gene was cloned into the pGL3-basic vector. For the mutant YY1-binding site, 5′-AAAGATGGAGAG-3′ was changed to 5′-ACACACACACAC-3′ in the pGL3-basic construct. These plasmids were transfected into HEK293T cells together with a pRL-TK plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) reagent. Luciferase assays were performed at 48 h after transfection using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) on a SpectraMax Luminescence Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices). Luciferase activity was expressed as the ratio between firefly and renilla luciferase activities.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation–quantitative real-time PCR and chromatin immunoprecipitation–sequencing

Chromatin from 1 × 107 WT thymocytes or enriched iNKT cells, which were purified by the depletion of CD8+ cells from the thymocytes of C57BL/6 Vα14-transgenic mice, was used for each chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiment. In brief, cells were first cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde. Then, chromatin was sonicated into 200–1000-bp fragments using a Misonix Sonicator 3000 (QSonica). The chromatin fragments were precleared with Protein G Agarose (Santa Cruz) and subsequently subjected to immunoprecipitation with 5 µg of the anti-YY1 (Abcam, ab12132) or control IgG (Abcam, ab27478) antibodies. The protein/DNA complexes were eluted and reverse cross-linked to free the DNA, which was further purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). For ChIP–quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), Platinum SYBR Green Supermix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for the detection of the Plzf promoter fragment. The primer sequences were as follows: forward, 5′-AGCCGGTGGTGATTTGCT-3′; and reverse, 5′-GATCGGGGAAGGGGTGTT-3′. For ChIP sequencing (ChIP-Seq), the DNA library was prepared and sequenced on a HiSeq 4000 system according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina). Illumina pipeline software was used for the sequencing analysis, and the sequences were aligned to the mouse genome (mm9, NCBI Build 37). HOMER software was used for motif discovery and peak calling (fold change ≥ 2, P < 0.0001, and peak score > 3). Alignment images were generated with the UCSC Genome Browser.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Results

YY1 is essential for iNKT cell development

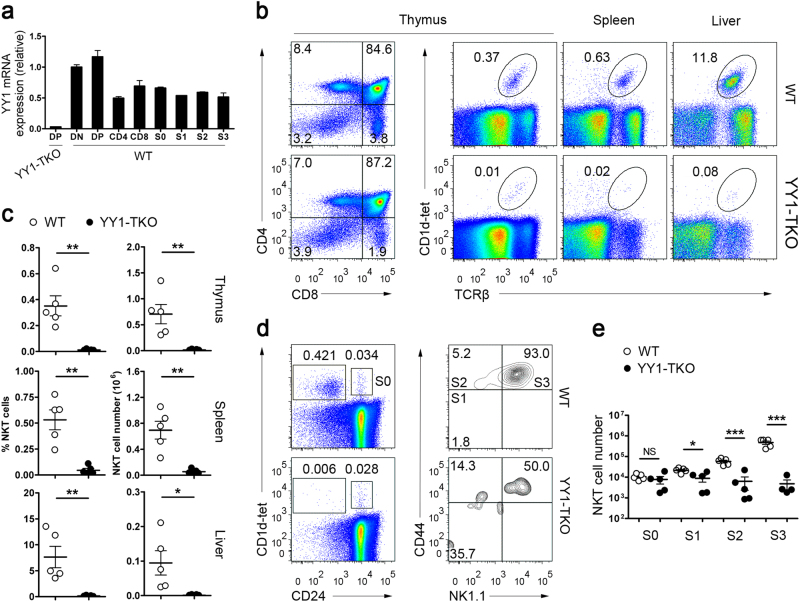

Before determining the effect of YY1 deficiency on iNKT cell development, we performed qPCR to assess the relative expression levels of YY1 in sorted thymocyte subpopulations and iNKT cells at various developmental stages from C57BL/6 WT mice. Thymocytes were sorted into CD4+ single-positive (SP), CD8+ SP, CD4−CD8− double-negative (DN), and CD4+CD8+ DP fractions. iNKT cells were sorted using CD1d tetramers loaded with the α-galactosylceramide analog PBS57 (CD1d-tet), according to the following criteria: CD1d-tet+CD24+ (stage 0); CD1d-tet+CD24−CD44−NK1.1− (stage 1); CD1d-tet+CD24−CD44+NK1.1− (stage 2); and CD1d-tet+CD24−CD44+NK1.1+ (stage 3). Using YY1-deficient DP thymocytes as a control, we showed that YY1 transcripts were widely expressed in DN, DP, CD4 SP, and CD8 SP thymocytes, as well as in iNKT cells, at various developmental stages (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1. Lack of iNKT cells in Yy1f/fCd4Cre/+ (YY1-TKO) mice.

a Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Yy1 expression in various thymic subsets (DN (CD4−CD8−), DP (CD4+CD8+), CD4 (CD4+ CD8−), and CD8 (CD4−CD8+)) and at various thymic iNKT cell developmental stages (S0 (CD1d-tet+CD24+), S1 (CD1d-tet+CD24−CD44−NK1.1−), S2 (CD1d-tet+CD24−CD44+NK1.1−), and S3 (CD1d-tet+CD24−CD44+NK1.1+)) in C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice. Data are representative of two independent experiments. b Frequency of iNKT (CD1d-tet+TCRβ+) cells in the thymus, spleen, and liver of WT and YY1-TKO mice. Cells were stained for CD4, CD8, TCRβ, and PBS57-loaded CD1d tetramer (CD1d-tet). Values indicate the percent of total mononuclear cells. Data are representative of five pairs of mice. c Frequency and numbers of iNKT cells in WT and YY1-TKO thymus, spleen, and liver. Each dot represents one mouse analyzed; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. d Analysis of iNKT cells at various developmental stages in the thymus of WT and YY1-TKO mice. Data shown are representative of five pairs of mice. e Enumeration of iNKT cells as described in d; NS not significant, *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001. Each dot represents one mouse analyzed

To investigate the role of YY1 in iNKT cell development, we crossed mice bearing two loxP-flanked Yy1 alleles (Yy1f/f) with mice bearing a Cre-recombinase gene driven by the promoter of the mouse CD4 gene (Cd4Cre/+) to generate YY1-TKO (Yy1f/f, Cd4Cre/+) mice in which Yy1 was deleted from thymocytes at the DP stage onward. We first examined conventional T-cell development in these mice and found that all thymocyte subsets were present in the YY1-TKO mice, although there was an ~50% reduction in the frequency of mature CD8+ SP cells (Fig. 1b).

Interestingly, as revealed by CD1d-tet and TCRβ staining, we found that the YY1-TKO mice exhibited an extremely low frequency (Fig. 1b) and number (Fig. 1c) of iNKT cells in the thymus, spleen, and liver, compared to WT mice. A detailed analysis of iNKT cell developmental stages, based on the expression of CD24, CD44, and NK1.1, showed that the YY1-TKO mice had numbers of stage 0 cells comparable to those of the WT mice. However, the YY1-TKO mice had far fewer numbers of stage 1, 2, and 3 cells, compared with the WT mice (Fig. 1d, e). These results indicated that YY1 deficiency affects iNKT cell development at very early developmental stages.

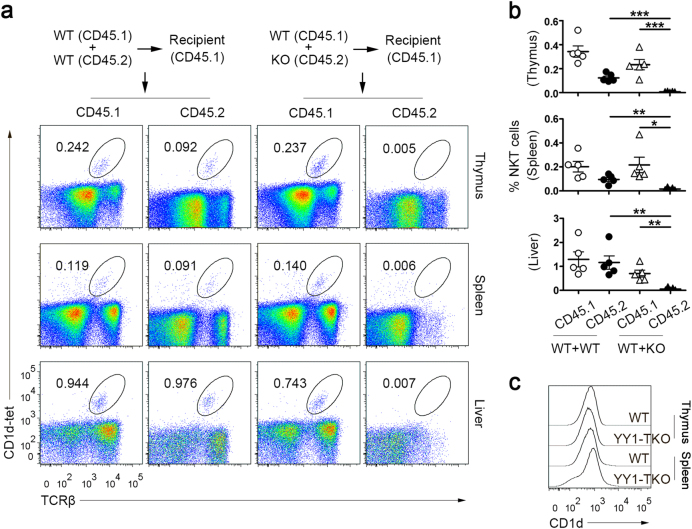

iNKT cell defect in YY1-TKO mice is T-cell intrinsic

Since iNKT cells are positively selected by lipid-presenting CD1d molecules expressed on DP thymocytes, we next addressed whether the iNKT cell developmental defect was T-cell intrinsic. We generated mixed-bone marrow chimeras in which irradiated CD45.1+ WT recipients were reconstituted with a 1:1 mixture of bone marrow cells from CD45.1+ WT and CD45.2+ WT or CD45.1+ WT and CD45.2+ YY1-TKO mice. After reconstitution, we determined the frequency (Fig. 2a) and number (Fig. 2b) of iNKT cells derived from both the donor WT and YY1-TKO fractions in the thymus, spleen, and liver of these chimeras. We observed that YY1-TKO donor bone marrow cells were unable to generate iNKT cells, even in the presence of normal DP thymocytes (Fig. 2a, b). We also examined CD1d expression levels in the thymocytes and splenocytes of WT and YY1-TKO mice and found that the expression levels of YY1-TKO mice were comparable to those of WT mice (Fig. 2c). Thus, these results confirmed that the iNKT defect in YY1-TKO cells is T-cell intrinsic.

Fig. 2. YY1-TKO thymocytes manifest T-cell-intrinsic defect in iNKT cell development.

a Mixed chimera experiments examining the contribution of WT and YY1-TKO bone marrow cells to iNKT populations in the thymus, spleen, and liver of the recipient mice. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate the percent of CD1d-tet+TCRβ+ cells. Data shown are representative of five pairs of mice. b Summary of iNKT cell frequencies as described in a; each dot represents one mouse analyzed; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. c CD1d surface expression on WT and YY1-TKO thymocytes and splenocytes. Data are representative of two independent experiments

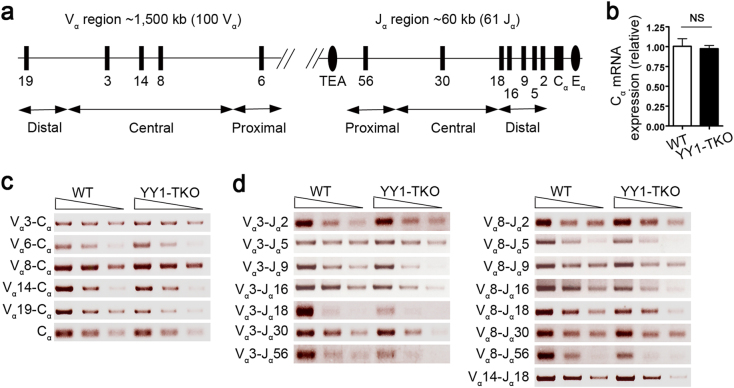

YY1-deficient DP thymocytes can rearrange the Vα14-Jα18 TCR

Because YY1 has been shown to spatially regulate VDJ recombination at the B-cell immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene (IgH) loci by contracting and bringing distally located V gene segments to proximal DJ segments,30 we hypothesized that YY1 may have a similar function in TCRα rearrangements and that this could impact iNKT cell development. Indeed, the schematic map of TCR Vα and Jα gene loci (Fig. 3a) indicated that the iNKT characteristic Vα14–Jα18 gene rearrangement would involve long-range contraction of the chromosome for the recombination of these genes.

Fig. 3. Analysis of Vα14–Jα18 TCRα rearrangements in YY1-TKO thymocytes.

a Schematic map showing selected proximal, central, and distal Vα and Jα segments. b Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Cα constant region gene expression, normalized to that of β-actin, in sorted CD69−TCRβintCD4+CD8+ thymocytes from WT and YY1-TKO mice; NS not significant. Data are representative of two independent experiments. c Vα-to-Cα and d Vα-to-Jα rearrangements, as assessed by semiquantitative RT-PCR analyses, in sorted WT and YY1-TKO thymocytes. cDNA template was normalized using Cα

To examine this possibility, we performed qPCR to quantify the transcripts of the TCRα constant region (Cα) in sorted DP (CD4+CD8+TCRβintCD69–) thymocytes from WT and YY1-TKO mice, and we found no difference in Cα usage (Fig. 3b). Next, we analyzed the extent of various Vα gene rearrangements and usage by semiquantitative reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR). We assessed the use of the proximal Vα6, central Vα3, Vα14, and Vα8, and distal Vα19 gene segments in WT and YY1-TKO DP thymocytes. There was slightly less usage of the distal Vα19 gene segment in YY1-TKO cells, whereas the usage of the proximal Vα6 and the central Vα3, Vα14, and Vα8 gene segments was comparable between WT and YY1-TKO DP thymocytes (Fig. 3c). These results indicated that YY1-TKO thymocytes exhibit largely normal usage of various Vα segments.

To characterize the usage of Jα segments for Vα–Jαrearrangements, we used primers for Vα3 and primers for the proximal Jα56, the central Jα30, and the distal Jα2, Jα5, Jα9, Jα16, and Jα18 gene segments. Rearrangements of Vα3–Jα2 and Vα3–Jα5 were found to be comparable between WT and YY1-TKO thymocytes, whereas recombination of the Vα3–Jα9, Vα3–Jα16, Vα3–Jα18, Vα3–Jα30, and Vα3–Jα56 gene segments was slightly reduced in YY1-TKO thymocytes (Fig. 3d). We also investigated the rearrangements of Vα8 to various Jα gene segments, and the results showed that there were only slight defects in the usage of Vα8–Jα16, Vα8–Jα18, and Vα8–Jα56 segments in the YY1-TKO thymocytes (Fig. 3d).

Finally, we examined the Vα14–Jα18 rearrangement that is characteristic of iNKT cells and found that this rearrangement was comparable between YY1-TKO and WT thymocytes (Fig. 3d). These data show that YY1-TKO thymocytes have largely intact TCRα gene rearrangements, especially the Vα14–Jα18 TCR necessary for iNKT cell development.

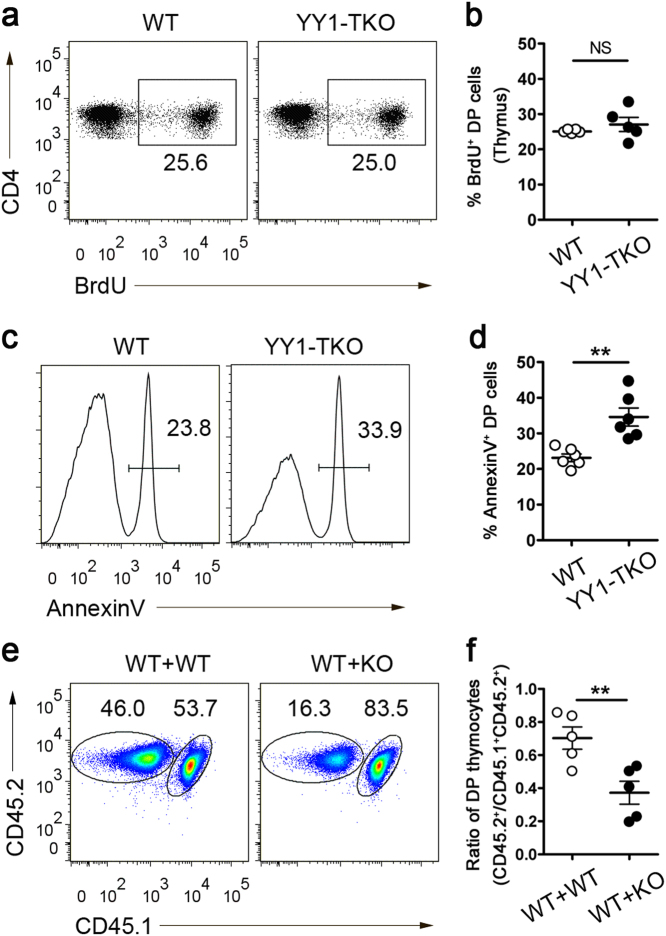

Impaired cell survival in YY1-deficient thymocytes

Previously, YY1 was shown to support B-cell proliferation and promote multiple myeloma cell survival by repressing the expression of the proapoptotic gene Bim.40 Hence, we examined whether YY1 regulates iNKT cell proliferation and survival at the DP precursor stage. We found that YY1-TKO DP thymocytes incorporated BrdU at a level equivalent to that of WT cells after a 20-h pulse (Fig. 4a, b), which indicated that the lack of YY1 did not affect thymocyte proliferation. Next, we examined the apoptosis rate of DP thymocytes after 20 h of culture and found that YY1-TKO DP thymocytes exhibited a higher frequency of annexin V+ cells compared to WT cells (Fig. 4c, d), indicating a defect in cell survival.

Fig. 4. Impaired thymocyte survival in YY1-TKO mice.

a Analysis of BrdU incorporation in WT and YY1-TKO DP thymocytes after a 20-h in vivo pulse. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate the percent of BrdU+ cells. Data shown are representative of five pairs of mice. b Frequency of BrdU+ thymocytes as in a. c Analysis of annexin V staining of WT and YY1-TKO DP thymocytes after 20 h of culture. Numbers indicated annexin V+ cells. Data shown are representative of six pairs of mice. d Frequency of annexin V+ thymocytes as described in c. e Mixed chimera experiments examining the contribution of WT (CD45.1+CD45.2+) and WT (CD45.2+) or WT (CD45.1+CD45.2+) and YY1-TKO (CD45.2+) bone marrow cells to the generation of DP cells in the thymus of recipient (CD45.1+) mice. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate the percent of CD45.1–CD45.2+ and CD45.1+CD45.2+ DP cells. Data shown are representative of five pairs of mice. f Summary of the ratio (CD45.1−CD45.2+:CD45.1+CD45.2+) of DP cell frequencies as described in e. Each dot in b, d, and f represents one mouse analyzed; NS not significant and **P < 0.01

To further confirm this defect in cell survival in vivo, we generated mixed-bone marrow chimeras in which irradiated CD45.1+ WT recipients were reconstituted with 1:1 mixture of bone marrow cells from CD45.1+CD45.2+ WT and CD45.2+ WT or CD45.1+CD45.2+ WT and CD45.2+ YY1-TKO mice. After reconstitution, we determined the frequency (Fig. 4e) and ratio (Fig. 4f) of DP cells derived from both the donor WT and YY1-TKO fractions. We observed significantly lower fractions of YY1-TKO DP thymocytes in the thymi of these chimeras. Consistent with this phenotype, YY1-TKO mice displayed a reduction in the absolute number of thymocytes compared with WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, YY1 deficiency was determined to affect the survival of developing thymocytes.

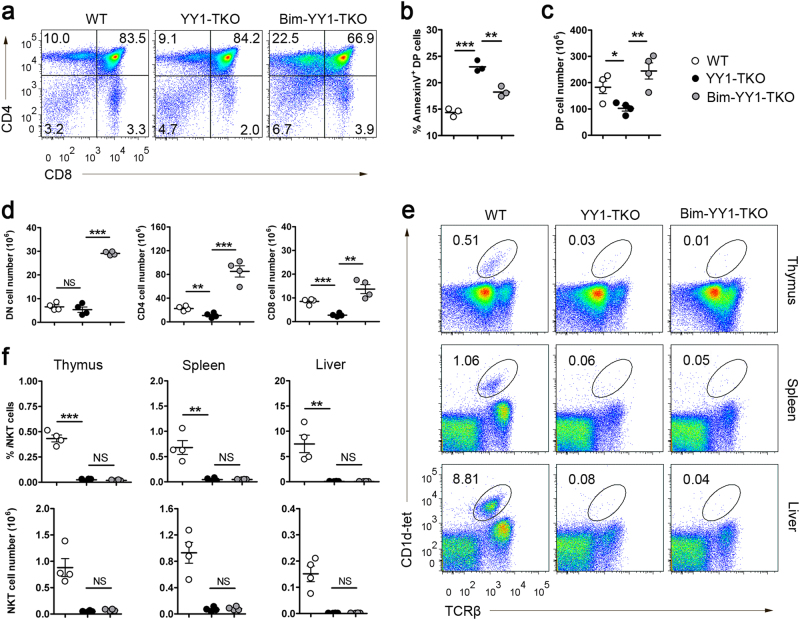

BIM deficiency fails to restore iNKT cell defect

To further address whether the impaired iNKT cell generation in YY1-TKO mice was solely due to the survival defect of the YY1-TKO thymocytes, we crossed YY1-TKO mice with Bim–/– mice to generate Bim-YY1-TKO mice (Fig. 5a). First, we ascertained that Bim–/– mice could generate iNKT cells (Supplementary Fig. 2) and that BIM deficiency could significantly increase both thymocyte survival (Fig. 5b) and the total number of DP (Fig. 5c), CD4 SP, and CD8 SP thymocytes in YY1-TKO mice (Fig. 5d). However, both the frequency and absolute numbers of iNKT cells in the thymus, spleen, and liver were still dramatically reduced in Bim-YY1-TKO mice (Fig. 5e, f). These data suggest that the impairment in iNKT cell development in YY1-TKO mice is not entirely due to defective thymocyte survival but could further involve compromised lineage maturation. Thus, YY1 may have a role in lineage differentiation of iNKT cells.

Fig. 5. BIM deletion fails to restore iNKT cell development in YY1-TKO mice.

a Thymic profile of WT, YY1-TKO, and Bim-YY1-TKO mice. Numbers in quadrants indicate the percent of cells in each. Data shown are representative of four pairs of mice. b Frequency of annexin V+ DP thymocytes of WT, YY1-TKO, and Bim-YY1-TKO mice after 20 h of culture. Data shown are representative of three pairs of mice. c Enumeration of DP thymocytes in WT, YY1-TKO, and Bim-YY1-TKO mice. d Enumeration of DN, CD4 SP, and CD8 SP thymocytes in WT, YY1-TKO, and Bim-YY1-TKO mice. e Analyses of iNKT cells in the thymus, spleen, and liver of WT, YY1-TKO, and Bim-YY1-TKO mice. Data shown are representative of four pairs of mice. f Frequencies and numbers of iNKT cells as described in e. Each dot in b, c, d, and f represents one mouse analyzed; NS not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001

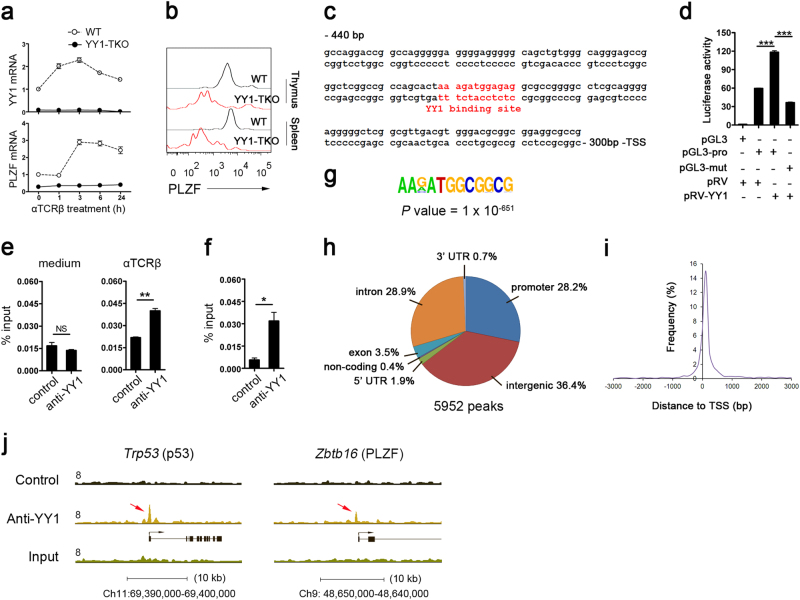

YY1 directly transactivates Plzf gene expression

TCR signaling is known to induce the expression of transcription factors critical for thymocyte differentiation. In iNKT cells, one critical lineage-specific transcription factor is PLZF.12, 13 Hence, we explored whether YY1 regulates PLZF to determine iNKT cell fate.

To test this possibility, we first assessed the expression of YY1 and PLZF in WT thymocytes activated by plate-coated anti-TCRβ antibodies. Yy1 mRNA was rapidly induced within 1 h and peaked at 3 h after activation, remaining detectable 24 h later (Fig. 6a). On the other hand, the induction of Plzf mRNA was delayed and lagged behind that of Yy1, remaining detectable after 1 h and plateauing at 3 h after activation. Interestingly, PLZF induction was absent in YY1-deficient thymocytes (Fig. 6a). We further assessed PLZF protein expression in iNKT cells from WT and YY1-TKO mice, and, surprisingly, we found that the YY1-deficient iNKT cells in the thymus and spleen lacked PLZF expression (Fig. 6b). In contrast, there was no reduction in the protein expression of Egr2 observed in YY1-TKO iNKT cells (Supplementary Fig. 3). Egr2 is a known PLZF-transcriptional activator that is also critical for iNKT cell development.14 Our data suggested that Egr2 alone was not sufficient to induce PLZF in the absence of YY1.

Fig. 6. YY1 binds and transactivates the Plzf promoter.

a Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Yy1 and Plzf expression in WT and YY1-TKO thymocytes after anti-TCRβ activation in vitro. Freshly isolated total thymocytes were treated at various times in 48-well plates that had been precoated with 1 μg/mL anti-mouse TCRβ antibody. Data are representative of three independent experiments. b FACS analyses of intracellular PLZF expression in iNKT cells obtained from the thymus and spleen of WT and YY1-TKO mice. Data are representative of two independent experiments. c Putative YY1-binding site in the 1-kb region upstream of the Plzf transcription start site (TSS). d YY1 transactivates the plzf promoter. HEK293T cells were transfected with either pGL3 (empty vector), pGL3-pro (luciferase expression driven by Plzf promoter), or pGL3-mut (pGL3-pro with mutated YY1-binding site) and pRV (empty retroviral vector) or pRV-YY1 (retroviral vector overexpressing YY1). Data are representative of four independent experiments. ***P < 0.001. e, f ChIP–quantitative PCR verification of YY1 binding to the region described in c using chromatin isolated from untreated or anti-TCR-activated WT thymocytes e and partially enriched iNKT cells f. Data are representative of three independent experiments. NS not significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. g YY1-binding motif based on ChIP-Seq analysis. h Peak distribution of YY1-binding sites in iNKT cells. i Frequency of enrichment near TSS in iNKT cells. j View of YY1 ChIP-Seq density profile at the promoter regions of Trp53 and Plzf (Zbtb16)

Given that PLZF is induced at stage 0 during iNKT cell development,12, 13 and this coincides with the block in iNKT cell maturation in YY1-TKO mice, we wondered if YY1 directly regulates PLZF expression. We examined the Plzf promoter sequence and located a conserved consensus YY1-binding motif ~360 base pairs upstream of the transcription start site (TSS; Fig. 6c). We proceeded to test the functionality of this putative YY1-binding site by overexpressing YY1 in HEK293T cells together with a luciferase plasmid driven by the Plzf promoter. We observed a substantial induction of luciferase activity when both YY1 and the WT Plzf promoter were introduced but not when the putative YY1-binding site was mutated (Fig. 6d). This indicated that YY1 could transactivate the Plzf promoter.

To determine whether YY1 directly modulates the activity of the Plzf promoter in vivo, we performed ChIP studies using anti-YY1 antibodies and cross-linked chromatin obtained from thymocytes before and 3 h after anti-TCRβ activation (Fig. 6e). Indeed, qPCR analyses with primers specific for the Plzf locus revealed that YY1 was recruited to the Plzf promoter only after anti-TCRβ stimulation. We also detected the binding of YY1 to the Plzf promoter using enriched thymic iNKT cells (Fig. 6f).

Finally, we performed unbiased, genome-wide studies of YY1-binding sites in iNKT cells isolated from the thymus of Vα14–Jα18 transgenic (Vα14-Tg) mice by ChIP and deep sequencing. Analysis of the obtained binding peaks revealed the consensus motif as the canonical YY1-binding sequence (Fig. 6g). A total of 5952 YY1-binding peaks were identified and found to be distributed primarily across promoter (28.2%), intron (28.9%), and intergenic (36.4%) regions, with lesser binding at exon (3.5%), noncoding (0.4%), 5′ untranslated region (UTR; 1.9%), and 3′ UTR (0.7%) regions (Fig. 6h and Supplementary Table 1). The promoter-binding peaks were highly enriched in the regions 1 kb upstream and downstream of the TSS (Fig. 6i). Among the target genes identified was p53 (Fig. 6j and Supplementary Table 1), which was previously shown to be bound by YY1 at the promoter region and to play a role in the regulation of thymocyte development. Notably, consistent with the aforementioned results, we identified one YY1-binding peak located immediately upstream of the Plzf TSS (Fig. 6j) that colocalized with the predicted YY1-binding site in the promoter region (Fig. 6c). Thus, the unbiased genome-wide studies presented further evidence of the direct binding of YY1 to the Plzf promoter and confirmed the critical role of YY1 in the regulation of iNKT cell development.

Taken together, these data indicated a critical and direct role for YY1 in the induction of the iNKT-specific transcription factor PLZF.

Discussion

Here, we describe a previously unappreciated but critically important role for the transcription factor YY1 in the regulation of thymic iNKT cell development. We show that YY1 regulates iNKT cell survival and also demonstrate that YY1 directly induces the expression of the transcription factor PLZF that drives the iNKT-lineage-specific differentiation program. These findings explain why the absence of YY1 leads to a profound block in iNKT cell maturation at a very early stage.

YY1 plays an important role in VDJ rearrangements at the IgH locus in B cells by contracting and looping chromosomes to facilitate gene rearrangements.30 The assembly of the iNKT-characteristic TCR would involve recombining distally located Vα14 and Jα18 gene segments. Hence, one could envisage that without YY1, the frequency and efficiency of Vα14–Jα18 recombination would be reduced and would thus affect iNKT cell development at a very early stage. We indeed found TCRα gene rearrangements to be slightly compromised at certain loci. However, the iNKT characteristic Vα14–Jα18 gene recombination could still occur in YY1-TKO mice, and this finding is consistent with the normal number of stage 0 iNKT cells in these mice. Thus, YY1 regulates the aspects of iNKT cell development other than just TCRα gene rearrangements.

The novel discovery of this study is the finding that YY1 regulates PLZF. We found YY1-TKO mice to have normal numbers of stage 0 iNKT cells but reduced numbers of stage 1, 2, and 3 iNKT cells. Given that the signature transcription factor PLZF is induced at stage 0, and PLZF deficiency caused iNKT cell block at stage 1,12, 13 we therefore hypothesized that YY1 could act upstream of PLZF in early iNKT cell development and play a role in lineage determination. Indeed, we observed YY1 expression to precede PLZF expression, and we found that YY1 binds to the promoter region of Plzf, indicating that YY1 participates in the regulation of PLZF during early iNKT cell differentiation.

A previous study showed that Egr2 directly controls PLZF expression in iNKT cells.15 We thus wondered whether YY1 also regulates Egr2, as YY1 was reported to be required for the transcriptional activation of Egr2 in Schwann cells to regulate peripheral myelination.41 However, we did not observe any reduction in Egr2 protein expression in YY1-deficient iNKT cells. Hence, it appeared that YY1 acts in parallel with Egr2 to induce PLZF expression during iNKT cell development. In addition, we performed both RT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 4) and ChIP-Seq (Supplementary Table 1) analyses to examine the possibility that YY1 may regulate iNKT cell formation through modulating the expression of other transcription factors known to be involved in iNKT cell generation, such as HEB, ETS, and GATA-3, and we found that these transcription factors were not affected. In addition, several groups had previously independently generated lists of YY1 target genes using ChIP-Seq or microarray analyses.29, 33, 42, 43 However, a closer examination of these lists revealed few common target genes among the different cell types studied, suggesting that the activity of YY1 may be modulated in various cell lineages or during cell maturation stages and under various physiological conditions.

We also observed increased apoptosis of DP precursors in YY1-TKO mice, suggesting that YY1 could also regulate thymocyte and, possibly, iNKT cell survival. Consistent with this finding, a recent report showed that YY1 promoted DP thymocyte survival by downregulating p53.44 Our ChIP-Seq data also indicated that p53 is a target gene of YY1 (Fig. 6). It is known that iNKT precursor cells are generated at the DP stage, and DP thymocyte survival is critical for the successful rearrangement of Vα14–Jα18 TCR.45, 46 However, we believe that rectifying the survival defect of YY1-deficient thymocytes would not fully restore iNKT development in YY1-TKO mice, as YY1 is also important for the induction of PLZF expression, as described above. Indeed, deletion of Bim in YY1-TKO mice caused an expansion of total thymocytes, including DP cells, but we could not detect any increase in iNKT cell populations. However, it remains to be determined whether YY1 has a role in the survival of iNKT cells once they are fully developed and exhibit normal PLZF expression.

In conclusion, our paper elucidated two important roles for YY1 in iNKT cell development by showing that YY1 not only regulates thymocyte survival but, more importantly, YY1 is required for the induction of PLZF expression.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Lim Wei Lee for sample processing and plasmid construction. We also thank other members of the laboratory for insightful discussion and the A*STAR Biomedical Research Council for grant support.

Author contributions

X.O., S.X., and K.-P.L. designed the experiments and wrote the paper. X.O., J.H., Y.H., and Y.-F.L. conducted the experiments.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Xijun Ou, Phone: +86-755-88018402, Email: ouxj@sustc.edu.cn.

Shengli Xu, Phone: +65-64070043, Email: xu_shengli@bti.a-star.edu.sg.

Kong-Peng Lam, Phone: +65-64070001, Email: lam_kong_peng@bti.a-star.edu.sg.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41423-018-0002-6).

References

- 1.Makino Y, Kanno R, Ito T, Higashino K, Taniguchi M. Predominant expression of invariant V alpha 14+ TCR alpha chain in NK1.1+ T cell populations. Int. Immunol. 1995;7:1157–1161. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.7.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fowlkes BJ, et al. A novel population of T-cell receptor alpha beta-bearing thymocytes which predominantly expresses a single V beta gene family. Nature. 1987;329:251–254. doi: 10.1038/329251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ceredig R, Lynch F, Newman P. Phenotypic properties, interleukin 2 production, and developmental origin of a “mature” subpopulation of Lyt-2- L3T4- mouse thymocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:8578–8582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budd RC, et al. Developmentally regulated expression of T cell receptor beta chain variable domains in immature thymocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1987;166:577–582. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.2.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salio M, Silk JD, Jones EY, Cerundolo V. Biology of CD1- and MR1-restricted T cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014;32:323–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godfrey DI, Berzins SP. Control points in NKT-cell development. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:505–518. doi: 10.1038/nri2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo J, et al. Regulation of the TCRalpha repertoire by the survival window of CD4(+)CD8(+) thymocytes. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:469–476. doi: 10.1038/ni791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu T, Simmons A, Yuan J, Bender TP, Alberola-Ila J. The transcription factor c-Myb primes CD4+CD8+ immature thymocytes for selection into the iNKT lineage. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:435–441. doi: 10.1038/ni.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callen E, et al. The DNA damage- and transcription-associated protein paxip1 controls thymocyte development and emigration. Immunity. 2012;37:971–985. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Cruz LM, Knell J, Fujimoto JK, Goldrath AW. An essential role for the transcription factor HEB in thymocyte survival, Tcra rearrangement and the development of natural killer T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:240–249. doi: 10.1038/ni.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egawa T, et al. Genetic evidence supporting selection of the Valpha14i NKT cell lineage from double-positive thymocyte precursors. Immunity. 2005;22:705–716. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovalovsky D, et al. The BTB-zinc finger transcriptional regulator PLZF controls the development of invariant natural killer T cell effector functions. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:1055–1064. doi: 10.1038/ni.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savage AK, et al. The transcription factor PLZF directs the effector program of the NKT cell lineage. Immunity. 2008;29:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarevic V, et al. The gene encoding early growth response 2, a target of the transcription factor NFAT, is required for the development and maturation of natural killer T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:306–313. doi: 10.1038/ni.1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seiler MP, et al. Elevated and sustained expression of the transcription factors Egr1 and Egr2 controls NKT lineage differentiation in response to TCR signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:264–271. doi: 10.1038/ni.2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dose M, et al. Intrathymic proliferation wave essential for Valpha14+ natural killer T cell development depends on c-Myc. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:8641–8646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812255106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mycko MP, et al. Selective requirement for c-Myc at an early stage of V(alpha)14i NKT cell development. J. Immunol. 2009;182:4641–4648. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walunas TL, Wang B, Wang CR, Leiden JM. Cutting edge: the Ets1 transcription factor is required for the development of NK T cells in mice. J. Immunol. 2000;164:2857–2860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Townsend MJ, et al. T-bet regulates the terminal maturation and homeostasis of NK and Valpha14i NKT cells. Immunity. 2004;20:477–494. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(04)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monticelli LA, et al. Transcriptional regulator Id2 controls survival of hepatic NKT cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:19461–19466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908249106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Gisbergen KP, et al. Mouse Hobit is a homolog of the transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 that regulates NKT cell effector differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:864–871. doi: 10.1038/ni.2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim PJ, et al. GATA-3 regulates the development and function of invariant NKT cells. J. Immunol. 2006;177:6650–6659. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacorazza HD, et al. The ETS protein MEF plays a critical role in perforin gene expression and the development of natural killer and NK-T cells. Immunity. 2002;17:437–449. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanic AK, et al. Cutting edge: the ontogeny and function of Va14Ja18 natural T lymphocytes require signal processing by protein kinase C theta and NF-kappa B. J. Immunol. 2004;172:4667–4671. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flanagan JR, et al. Cloning of a negative transcription factor that binds to the upstream conserved region of Moloney murine leukemia virus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:38–44. doi: 10.1128/MCB.12.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi Y, Seto E, Chang LS, Shenk T. Transcriptional repression by YY1, a human GLI-Kruppel-related protein, and relief of repression by adenovirus E1A protein. Cell. 1991;67:377–388. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park K, Atchison ML. Isolation of a candidate repressor/activator, NF-E1 (YY-1, delta), that binds to the immunoglobulin kappa 3’ enhancer and the immunoglobulin heavy-chain mu E1 site. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:9804–9808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hariharan N, Kelley DE, Perry RP. Delta, a transcription factor that binds to downstream elements in several polymerase II promoters, is a functionally versatile zinc finger protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:9799–9803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleiman E, Jia H, Loguercio S, Su AI, Feeney AJ. YY1 plays an essential role at all stages of B-cell differentiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E3911–E3920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606297113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu H, et al. Yin Yang 1 is a critical regulator of B-cell development. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1179–1189. doi: 10.1101/gad.1529307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trabucco SE, Gerstein RM, Zhang H. YY1 regulates the germinal center reaction by inhibiting apoptosis. J. Immunol. 2016;197:1699–1707. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banerjee A, et al. YY1 is required for germinal center B cell development. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0155311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green MR, et al. Signatures of murine B-cell development implicate Yy1 as a regulator of the germinal center-specific program. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:2873–2878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019537108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hwang SS, et al. Transcription factor YY1 is essential for regulation of the Th2 cytokine locus and for Th2 cell differentiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:276–281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214682110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu B, et al. Epigenetic landscapes reveal transcription factors that regulate CD8(+) T cell differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2017;18:573–582. doi: 10.1038/ni.3706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang SS, et al. YY1 inhibits differentiation and function of regulatory T cells by blocking Foxp3 expression and activity. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10789. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon HK, Chen HM, Mathis D, Benoist C. Different molecular complexes that mediate transcriptional induction and repression by FoxP3. Nat. Immunol. 2017;18:1238–1248. doi: 10.1038/ni.3835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang GZ, Goff SP. Regulation of Yin Yang 1 by tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:21890–21900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.660621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ou X, Xu S, Li YF, Lam KP. Adaptor protein DOK3 promotes plasma cell differentiation by regulating the expression of programmed cell death 1 ligands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:11431–11436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400539111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Potluri V, et al. Transcriptional repression of Bim by a novel YY1-RelA complex is essential for the survival and growth of multiple myeloma. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e66121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He Y, et al. Yy1 as a molecular link between neuregulin and transcriptional modulation of peripheral myelination. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:1472–1480. doi: 10.1038/nn.2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu L, et al. Genome-wide survey by ChIP-seq reveals YY1 regulation of lincRNAs in skeletal myogenesis. EMBO J. 2013;32:2575–2588. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen L, et al. Genome-wide analysis of YY2 versus YY1 target genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4011–4026. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen L, Foreman DP, Sant’Angelo DB, Krangel MS. Yin Yang 1 promotes thymocyte survival by downregulating p53. J. Immunol. 2016;196:2572–2582. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bezbradica JS, Hill T, Stanic AK, Van Kaer L, Joyce S. Commitment toward the natural T (iNKT) cell lineage occurs at the CD4+8+ stage of thymic ontogeny. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:5114–5119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408449102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gapin L, Matsuda JL, Surh CD, Kronenberg M. NKT cells derive from double-positive thymocytes that are positively selected by CD1d. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:971–978. doi: 10.1038/ni710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.