Abstract

We describe the clinical features of four Japanese families with moderate sensorineural hearing loss due to the OTOG gene variant. We analyzed 98 hearing loss-related genes in patients with hearing loss originally from the Okinawa Islands using next-generation sequencing. We identified a homozygous variant of the gene encoding otogelin NM_001277269(OTOG): c.330C>G, p.Tyr110* in four families. All patients had moderate hearing loss with a slightly downsloping audiogram, including low frequency hearing loss without equilibrium dysfunction. Progressive hearing loss was not observed over the long-term in any patient. Among the three patients who underwent newborn hearing screening, two patients passed the test. OTOG-associated hearing loss was considered to progress early after birth, leading to moderate hearing loss and the later stable phase of hearing loss. Therefore, there are patients whose hearing loss cannot be detected by NHS, making genetic diagnosis of OTOG variants highly useful for complementing NHS in the clinical setting. Based on the allele frequency results, hearing loss caused by the p.Tyr110* variant in OTOG might be more common than we identified. The p.Tyr110* variant was reported in South Korea, suggesting that this variant is a common cause of moderate hearing loss in Japanese and Korean populations.

Subject terms: Medical genetics, Diseases

Hearing loss: Newborn hearing tests can miss inherited OTOG deficiency

People born with mutations in a gene linked to moderate hearing loss don’t always show problems during newborn hearing screening and may benefit from genetic screening. Testing for this gene, OTOG, which encodes a protein expressed in sensory cells of the inner ear, could thus be an important complement to newborn hearing screening for individuals with a family history of hearing loss who may benefit from early medical intervention. A Japan-based team led by Akira Ganaha from the University of Miyazaki studied seven patients with hearing loss from four unrelated families living on the Japanese archipelago of Okinawa. Each had two copies of a recessive mutation in OTOG, a variant previously documented only in South Korea. Of the three who underwent newborn hearing tests, only one was diagnosed with hearing deficiency at birth.

Introduction

To date, over 100 causative genes have been identified for nonsyndromic deafness, of which 70% follow a recessive inheritance pattern1,2. A large majority of recessive variants are associated with congenital, nonprogressive, and severe-to-profound hearing loss3. Compared with severe-to-profound hearing loss, mild-to-moderate hearing loss in children has been less well characterized. OTOG (DFNB18B) is a causative gene of mild-to-moderate nonsyndromic hearing loss4,5. OTOG encodes otogelin, which is a noncollagenous protein specific to the inner ear6. Hearing loss in OTOG knockout mice is bilateral and highly progressive immediately after birth, ranging from mild-to-profound7. Five causative variants in OTOG have been reported in four families to date4,5,8. Although only four families have been reported to date with OTOG mutations, the onset and long-term course of hearing loss and complications of disequilibrium have not been clarified.

We analyzed 98 genes related to hearing loss using next-generation sequencing (NGS) in patients originally from the Okinawa Islands. NGS revealed the presence of a homozygous variant in exon 4 of OTOG, c.330C>G, p.Tyr110*, in four families. In this study, we investigated the onset and long-term clinical features of hearing loss patients with the OTOG p.Tyr110* variant. Based on the allele frequency in the 1000 Genomes Project and in this study, hearing loss caused by the OTOG gene might be more common than reported previously.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Seven affected patients from four unrelated families were investigated (Fig. 1). Clinical history was taken from all patients, and physical examinations were performed, including otoscopy, hearing tests, and computed tomography (CT) of the temporal bones. Depending on each patient’s ability, hearing level was determined using auditory steady-state response (ASSR), auditory brainstem response (ABR), conditioned orientated response, or pure tone audiogram (PTA). Hearing level was defined as the average hearing threshold at 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 kHz. Hearing was described as follows: normal, < 20 dB; mild impairment, 21–40 dB; moderate impairment, 41–70 dB; severe impairment, 71–90 dB; and profound impairment, > 91 dB.

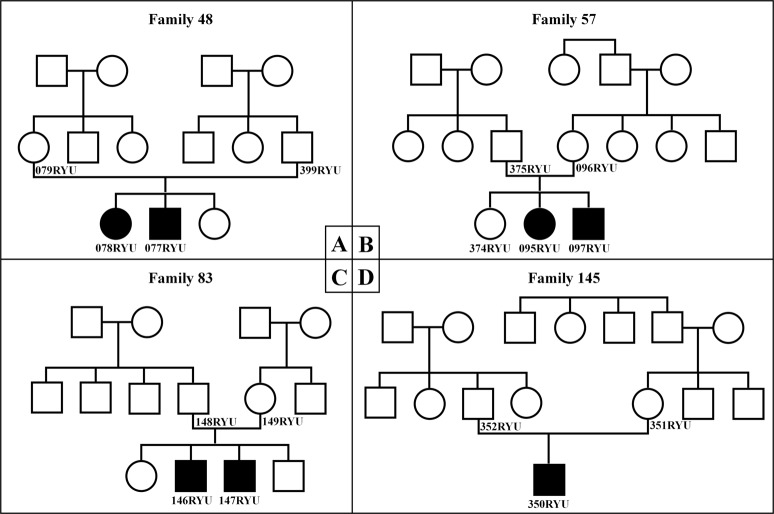

Fig. 1. Pedigree of the seven reported patients.

Pedigrees of (a) patient 078RYU (III-1) and 077RYU (III-2), (b) patient 095RYU (III-2) and 097RYU (III-3), (c) patient 146RYU (III-2) and 147RYU (III-3), and (d) patient 350RYU (III-1). Hearing loss occurred in an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern

Prior to enrollment, all subjects provided written informed consent. Our research protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Boards of the University of Miyazaki and University of the Ryukyus.

OTOG genotyping

NGS

Targeted resequencing for hearing loss (family 48) or whole-exome sequencing (family 57, 83, 145) was performed as described previously9,10. Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted from whole-blood cells using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). For targeted resequencing, a customized HaloPlex Target Enrichment Panel (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to enrich each DNA sample from the families for 98 candidate genes for hearing loss, including OTOG. Each enriched DNA samples were sequenced with the MiSeq System (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Variants from sequencing data were called using the SureCall pipeline (Agilent Technologies). For whole-exome sequencing analysis, the SureSelect Human All Exon V6 Kit (Agilent Technology, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for capture, and the HiSeq2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for sequencing. Reads were aligned to CRC37 using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner. Variants were called using the GATK Unified Genotyper and ANNOVA (http://annover.openbioinfomatics.org/en/latest/).

Sanger sequencing

To confirm the coding sequence and variant, Sanger sequencing of the OTOG gene was performed in all subjects. PCR was performed as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 40 s, 64 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR was performed on a programmable thermal cycler (Verti 96-Well Thermal Cycler; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR products were purified using the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and sequenced directly using an ABI PRISM 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The sequences were aligned and compared using the BLAST program with known human genome sequences available in the GenBank database.

PCR–restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of OTOG

We surveyed the substitutions in exon 4 of OTOG (c.330C>G, p.Tyr110*) in 100 healthy unrelated Okinawan individuals used as controls. The genotypes of the p.Tyr110* variants were detected by digestion of the PCR product with the restriction enzyme BsaXI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA).

Results

NGS identified a homozygous variant in exon 4 of the OTOG gene, c.330C>G, p.Tyr110*, in seven patients with moderate sensorineural hearing loss (Figs. 1, 2).

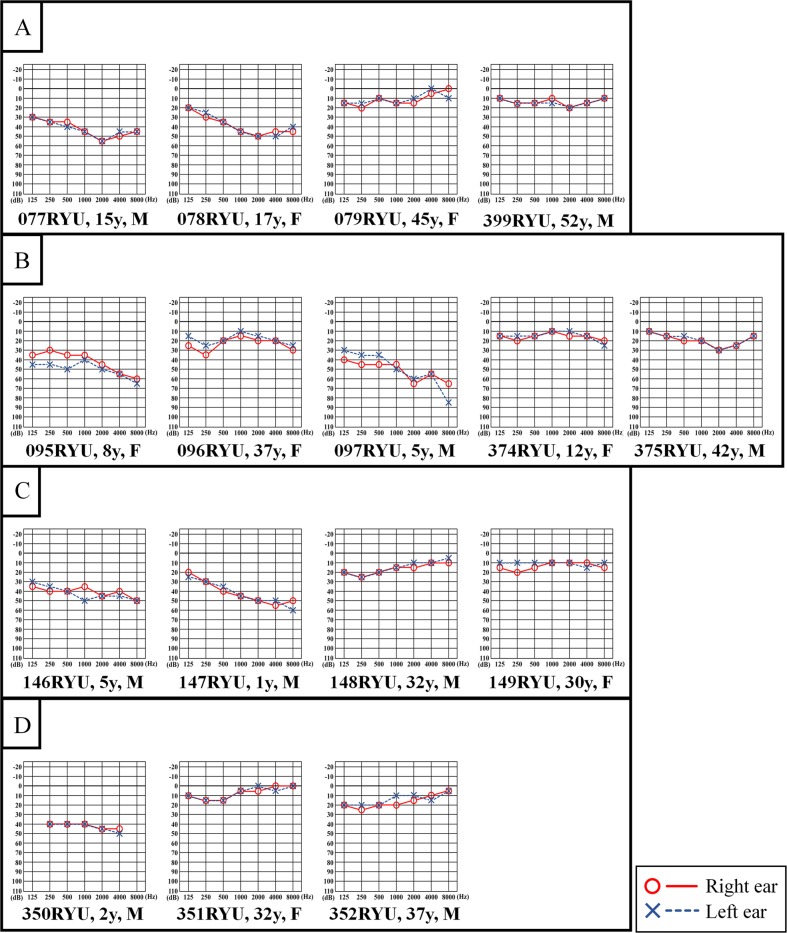

Fig. 2. Pure tone audiometry of the patients and family members.

a Audiograms in family 48, (b) family 57, (c) family 83, and (d) family 145 indicate moderate hearing loss in the patients. Hearing thresholds for the right ear are represented by red circles, and the thresholds for the left ear are represented by the blue Xs

Table 1 shows the clinical features and the results of examinations in all patients. Newborn hearing screening (NHS) was performed in three patients; two of these patients passed the NHS. PTA showed moderate sensorineural hearing loss with a slightly downsloping pattern involving low frequency loss in all patients (Fig. 2). Distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAE) showed no response in all patients (Table 1) at their first visit to our hospital. ABR or ASSR was performed in six of the seven patients, which showed consistent results with the PTA (Table 1). No patient exhibited vertigo or abnormal findings in the middle or inner ear on temporal bone high-resolution CT (Table 1). Five of the seven patients had been using bilateral hearing aids. None of the patients showed progression of their hearing loss during the follow-up period (100 ± 68 months). In particular, two patients (077RYU and 078RYU in Table 1) did not show progression of hearing loss for more than 10 years. An articulation test was performed in six of the seven patients. At their first visit to our hospital, all patients were observed to be developing normally in areas unrelated to speech, language, and hearing. All six patients with the OTOG variant demonstrated fewer articulation errors at the age of 4 or 5 years. However, four patients aged 10 years and over demonstrated an improvement in articulation skills with age regardless of the presence or absence of a hearing aid.

Table 1.

Summary of the clinical findings of the seven patients

| Family | Patient | Age at first visit (years) | Sex | NHS | First PTA | Latest PTA | DPOAE | ABR | ASSR | Follow-up period (months) | Vertigo | CT findings | HA | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rt. | Lt. | Rt. (dB) | Lt. (dB) | Rt. (dB) | Lt. (dB) | Rt. | Lt. | Rt. (dB) | Lt. (dB) | Rt. (dB) | Lt. (dB) | ||||||||||||||

| 500 | 1 k | 2 k | 4 k | 500 | 1 k | 2 k | 4 k | ||||||||||||||||||

| 48 | 077RYU | 7 | M | NA | 46 | 45 | 47 | 45 | Negative | Negative | NA | NA | NA | 155 | No | No abnormality | Yes | ||||||||

| 078RYU | 3 | F | NA | 47 | 45 | 43 | 43 | Negative | Negative | 50 | 60 | NA | NA | 232 | No | No abnormality | Yes | ||||||||

| 57 | 095RYU | 5 | F | NA | 42 | 42 | 38 | 45 | Negative | Negative | 50 | 50 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 50 | 40 | 40 | 50 | 50 | 76 | No | No abnormality | No | |

| 097RYU | 2 | M | NA | 47 | 51 | 51 | 48 | NA | NA | 60 | 60 | 60 | 50 | 50 | 60 | 60 | 50 | 50 | 60 | 70 | No | No abnormality | Yes | ||

| 83 | 146RYU | 4 | M | Pass | Pass | 40 | 40 | 40 | 45 | Negative | Negative | 40 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 40 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 56 | No | No abnormality | No |

| 147RYU | 0 | M | Pass | Refer | 41 | 45 | 41 | 41 | Negative | Negative | 40 | 50 | 40 | 30 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 50 | 50 | 61 | No | No abnormality | Yes | |

| 145 | 350RYU | 0 | M | Refer | Refer | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | Negative | Negative | 50 | 60 | 40 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 60 | 50 | 60 | 47 | No | No abnormality | Yes |

NHS newborn hearing screening, PTA pure tone audiometry, DPOAE distortion product otoacoustic emissions, ABR auditory brainstem response, ASSR auditory steady-state response, HA hearing aid, Rt. right, Lt. left, NA not assessed

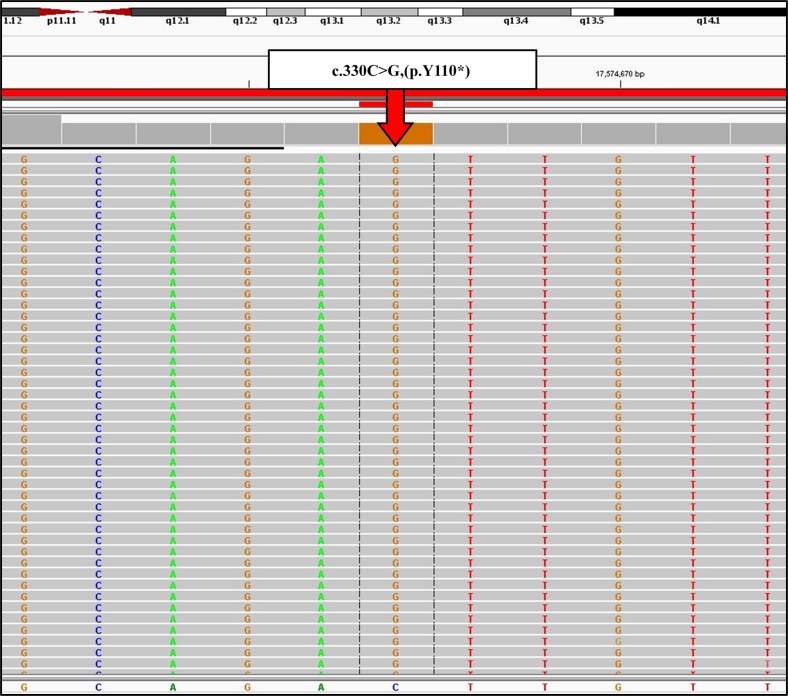

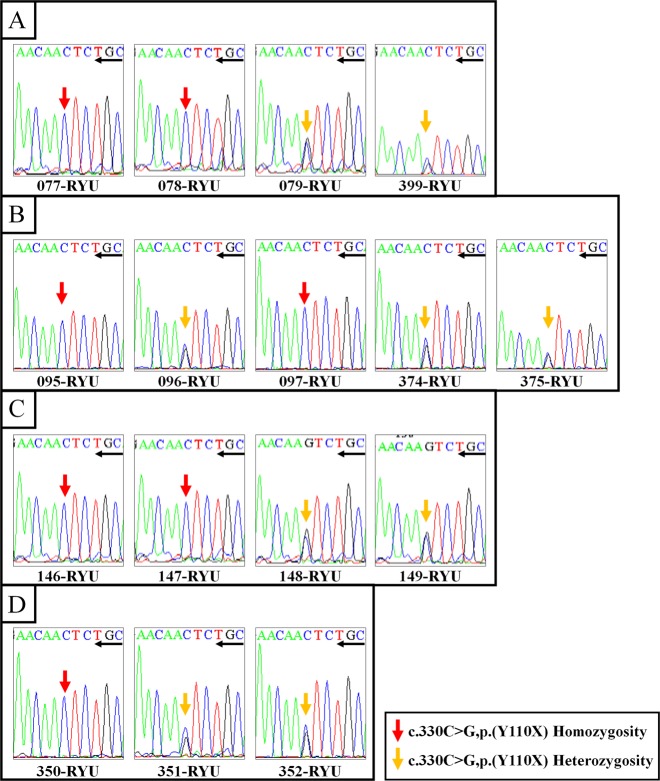

Figure 3 shows the results of NGS of the OTOG gene variant, c.330C>G, p.Tyr110*, on the Integrative Genome Viewer. The presence of the homozygous variant of p.Tyr110* in patients and the heterozygous variant in their parents was confirmed by direct sequencing analysis (Fig. 4). Allele frequency analysis of 100 control individuals with normal hearing using PCR-RFLP revealed one heterozygous variant of p.Tyr110*, but no homozygous variants (data not shown).

Fig. 3. Integrative Genomics Viewer images of NGS analysis of the OTOG gene.

Integrative Genomics Viewer images of NGS analysis of the OTOG gene (forward sequence) for 077RYU (family 48). The arrow indicates the variant nucleotide. The reference sequence is presented at the bottom of Fig. 3

Fig. 4. Examples of Sanger sequence analysis of the OTOG gene.

OTOG gene sequencing profiles of the patients. Sanger sequencing diagram (reverse sequence) for (a) family 48, (b) family 57, (c) family 83, and (d) family 145. Red arrows indicate the homozygous variant of p.Tyr110X, yellow arrows indicate the heterozygous variant

Discussion

OTOG (DFNB18B) is a causative gene of nonsyndromic mild-to-moderate hearing loss that follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Five causative variants in OTOG have been reported in four families to date4,5,8 (Table 2). OTOG encodes otogelin protein and is expressed in the sensory epithelium of the inner ear, including the tectorial membrane, otoconial membranes in the utricle and saccule, and cupula that covers the crista ampullaris of the semicircular canal in the vestibular organ6. In the cochlea, OTOG appears to be involved in organizing the fibrillar network of the tectorial membrane and likely plays a role in determining the resistance of this membrane to sound stimulation7. Hearing loss in OTOG knockout mice is bilateral and highly progressive immediately after birth, ranging from mild-to-profound7. However, it has not been clarified whether OTOG-associated hearing loss in humans is congenital or progresses early after birth. In this study, NHS was performed using automated auditory brainstem responses in three patients, and two patients passed the NHS. In both patients, moderate hearing loss of more than 40 dB was confirmed by hearing tests including PTA, DPOAE, ABR, and ASSR at the first visit of our hospital. These results indicate that hearing loss due to OTOG variants is not congenital, but that hearing loss immediately after birth may be genetically determined. There is a risk that patients with OTOG variants may pass the NHS and miss the opportunity to receive early medical intervention for hearing loss. Therefore, accurate diagnosis of such genetic variants is clinically useful to complement NHS and prevent overlooking hearing loss that develops immediately after birth.

Table 2.

Clinical findings of previously described and our families

| Schraders et al.4 | Danial-Farran N8 | Yu et al.5 (2018) | Our families | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Dutch family | Spanish family | Arab family | Korean family | Japanese family | |||

| Family 48 | Family 57 | Family 83 | Family 145 | |||||

| Variant | c.5508delC, p.(Ala1838Profs*31) | c.6347C>T,p.(Pro2116Leu) / c.6559C>T,p.(Arg2187*) | c.7453C>T,p.(Arg2485*) | c.330C>G,p.(Tyr110*) | c.330C>G, p.(Tyr110*) | |||

| Homozygous | Compound heterozygous | Homozygous | Homozygous | Homozygous | ||||

| Severity of Hearing loss | Mild-to-moderate | Mild-to-moderate | NA | Mild | Moderate | |||

| Shape of audiogram | Flat to shallow U-shaped | Slightly downsloping | NA | Slightly downsloping | Slightly downsloping | |||

| Vestibular dysfunctiona | + | + | NA | − | − | NA | NA | NA |

| Symptom of Vertigob | Delayed motor development | − | NA | − | − | |||

aThe results of equilibrium function test using caloric test and/or rotary chair test

bClinical episode of vertigo or suspected vestibular dysfunction

Hearing loss due to OTOG variants shows a slightly downsloping audiogram or a U-shaped to flat audiogram, and the pattern is similar to that of hearing loss due to variants in TECTA, which is also expressed in the tectorial membrane4. In the present report, a slightly downsloping shaped audiogram was detected in all patients, and an increase in the low frequency threshold was especially characteristic. In addition, based on the observation of the clinical course of the same patients’ hearing over 10 years, it was clinically determined that hearing loss due to p.Tyr110* is not progressive over time. Thus, we determined that hearing loss due to p.Tyr110* is characterized by onset immediately after birth, leading to moderate hearing loss with a slightly downsloping shaped audiogram with nonprogressive features.

Equilibrium dysfunction and associated motor developmental delay have been reported in patients with OTOG variants4. A previous study reported that vestibular dysfunction was present in OTOG knockout mice7. None of our seven patients had episodes of vertigo or motor developmental delay (Table 2). A caloric test could be performed in only one patient (077RYU); however, no obvious canal paresis was observed. A previous report with the same genetic variant as our report indicated that there was no equilibrium dysfunction in the patients5. The possibility cannot be excluded that the differences in phenotype between the previous report4 and the present report are associated with different variants. However, the genotype–phenotype correlation is not clear, as only eight families, including our four families, with hearing loss caused by OTOG variants have been reported to date.

Among the hereditary hearing loss, the c.235delC in GJB2 gene was identified as the most frequent pathogenic variant, followed by p.H723R in SLC26A4 in Japanese population11. The allele frequency of c.235delC in GJB2 is 1% and that of the p.H723R in SLC26A4 is 0.5% in the 1000 Genomes Project (1000G). The p.Tyr110* variant was reported in only the Japanese population in the 1000G with an allele frequency of 0.5%. In this study, the allele frequency of the p.Tyr110* in Okinawan control individuals was identified in 0.5% (1/200), with the same allele frequency in 1000G and that of p.H723R in SLC26A4. Which means that one out of 40,000 may have mild-to-moderate hearing loss due to the p.Tyr110*. Based on these results, hearing loss caused by p.Tyr110* in OTOG might be more common than we identified. However, only eight families, including our four families, with hearing loss caused by OTOG variants have been reported to date, and this is the first report of hearing loss caused by this variant in the Japanese population. There is a possibility of underestimation of the prevalence of hearing loss caused by the OTOG gene in that the patients with the variant might be excluded from the genomic research because of mild phenotype12.

The Okinawa Islands are the southwestern-most islands of the Japanese archipelago. Previous studies suggested that there were substantial ancestral differences between the Okinawa Islands and the main islands of Japan13. The common variant p.Tyr110* identified in all four families in this report is considered to be the result of a founder effect by a common ancestor. The same variant was reported from Korea in 20185, which also suggests that the variant has common ancestor in Korea5. Altogether, it is possible that p.Tyr110* may be a common cause of moderate hearing loss in Japanese and Korean5 populations.

In conclusion, we identified the variant c.330C>G, p.Tyr110* in OTOG in seven patients of four families with moderate hearing loss in the Japanese population. Hearing loss was considered to occur immediately after birth, showing a moderate and slightly downsloping audiogram, and was nonprogressive thereafter. None of the families had symptoms of vestibular disorders. NM_001277269(OTOG): c.330C>G, p.Tyr110* was considered to be a highly frequent causative variant of mild-to-moderate hearing loss in Japanese and Korean5 populations. The present results with a long-term follow-up will improve the genetic counseling of patients with mutations in OTOG.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. K. Fukushima of Hayashima Clinic, Okayama, Japan, for insightful comments and suggestions. We also thank audiologist K. Yoza from the University of the Ryukyus and T. Yuchi of University of Miyazaki for their assistance in this study. This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) No. 17K11337 and Grant-in-Aid for Clinical Research from Miyazaki University Hospital.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Akira Ganaha, Tadashi Kaname, Kumiko Yanagi, Tetsuya Tono, Teruyuki Higa, Mikio Suzuki

References

- 1.Morton CC, Nance WE. Newborn hearing screening–a silent revolution. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:2151–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lenz DR, Avraham KB. Hereditary hearing loss: from human mutation to mechanism. Hear Res. 2011;281:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duman D, Tekin M. Autosomal recessive nonsyndromic deafness genes: a review. Front. Biosci. 2012;17:2213–2236. doi: 10.2741/4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schraders M, et al. Mutations of the gene encoding otogelin are a cause of autosomal-recessive nonsyndromic moderate hearing impairment. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:883–889. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu S, et al. A novel early truncation mutation in OTOG causes prelingual mild hearing loss without vestibular dysfunction. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2019;62:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen-Salmon M, Mattei MG, Petit C. Mapping of the otogelin gene (OTGN) to mouse chromosome 7 and human chromosome 11p14.3: a candidate for human autosomal recessive nonsyndromic deafness DFNB18. Mamm. Genome. 1999;10:520–522. doi: 10.1007/s003359901033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simmler MC, et al. Targeted disruption of otog results in deafness and severe imbalance. Nat. Genet. 2000;24:139–143. doi: 10.1038/72793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danial-Farran N, et al. Genetics of hearing loss in the Arab population of Northern Israel. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;26:1840–1847. doi: 10.1038/s41431-018-0218-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganaha A, et al. Am Progressive macrothrombocytopenia and hearing loss in a large family with DIAPH1 related disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2017;173:2826–2830. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasaki H, et al. Definitive diagnosis of mandibular hypoplasia, deafness, progeroid features and lipodystrophy (MDPL) syndrome caused by a recurrent de novo mutation in the POLD1 gene. Endocr. J. 2018;65:227–238. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ17-0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Usami S, Nishio SY, Nagano M, Abe S, Yamaguchi T. Deafness Gene Study Consortium. Simultaneous screening of multiple mutations by invader assay improves molecular diagnosis of hereditary hearing loss: a multicenter study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsukada K, Nishio S, Usami S, Deafness Gene Study Consortium. A large cohort study of GJB2 mutations in Japanese hearing loss patients. Clin. Genet. 2010;78:464–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Japanese Archipelago Human Population Genetics Consortium. Jinam T, et al. The history of human populations in the Japanese Archipelago inferred from genome-wide SNP data with a special reference to the Ainu and the Ryukyuan populations. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;57:787–795. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2012.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]