Abstract

PURPOSE:

To describe the frequency, content, dynamics, and patterns of cost conversations in academic medical oncology across tumor types.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

We reviewed 529 audio recordings between May 3, 2012, to September 23, 2014, from a prospective three-site communication study in which patients at any stage of management for any solid tumor malignancy were seen in routine oncology appointments. Recordings were deidentified, transcribed, and flagged for any mention of cost. We coded encounters and used qualitative thematic analysis.

RESULTS:

Financial issues were discussed in 151 (28%) of 529 recordings. Conversations lasted shorter than 2 minutes on average. Patients/caregivers raised a majority of discussions (106 of 151), and 40% of cost concerns raised by patients/caregivers were not verbally acknowledged by clinicians. Social service referrals were made only six times. Themes from content analysis were related to insurance eligibility/process, work insecurity, cost of drugs, cost used as tool to influence medical decision making, health care–specific costs, and basic needs. Financial concerns influenced oncology work processes via test or medication coverage denials, creating paperwork for clinicians, potentially influencing patient involvement in trials, and leading to medication self-rationing or similar behaviors. Typically, financial concerns were associated with negative emotions.

CONCLUSION:

Financial issues were raised in approximately one in four academic oncology visits. These brief conversations were usually initiated by patients/caregivers, went frequently unaddressed by clinicians, and seemed to influence medical decision making and work processes and contribute to distress. Themes identified shed light on the kinds of gaps that must be addressed to help patients with cancer cope with the rising cost of care.

INTRODUCTION

The cost of cancer care in the United States is projected to balloon to $157 billion by 2020.1,2 This cost is transferred to patients, resulting in financial burden, increased declarations of bankruptcy, decreased adherence to treatment, poorer quality of life, and worse survival.3,4 Although aware of financial issues, oncologists feel ill equipped to address them.5-8 In an effort to aid oncologists in addressing cost, the ASCO Value Framework highlights the toxicity and quality of life impact of care costs,9,10 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) evidence blocks now take cost into consideration.11 Although these initiatives may not yet be suited for routine clinical use and may focus too heavily on comparing costs of two treatments (ASCO) or on costs of medications (NCCN), they highlight the need for specificity about how clinicians and patients broach this subject.

Little is known about the actual content of discussions about costs and other financial issues between patients and providers in real-world practice. Without this insight, it is difficult to offer improved training or devise interventions to adequately address costs in oncology care. Although the landscape of addressing value and cost of care in oncology is rapidly evolving, to shed some light on the broad range of economic stressors in cancer care and begin to gain insights into what to do about them, we turned to clinical conversations in real time. In this study, we sought to describe the baseline frequency, content, dynamics, and patterns of cost conversations in diverse academic settings using qualitative and quantitative methods.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Design

We analyzed audio recordings of clinical interactions from three different oncology clinics. Recordings were collected as part of a three-site prospective parent study.12 This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic and University of Southern California institutional review boards. Encounters in the parent study were routine oncology visits between patients at any stage of the cancer continuum (new diagnosis, active therapy, surveillance, or end stage) and their clinicians. Participants agreed to have their encounters recorded without knowledge of the hypotheses of the study (eg, only that this was a communication study). Other details about the parent study were published previously.12 For this analysis, we characterized communication about cost operationalized as any discussion of financial issues in routine oncology encounters between clinicians and their patients/lay caregivers.

Participants

Clinicians were eligible if they practiced at least once per week. They were recruited from three different sites: an Upper Midwest National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center, a Southern California National Cancer Institute–designated university cancer center, and a Southern California county hospital site affiliated with that cancer center that functions as a safety-net hospital. Clinicians provided written consent and completed a baseline survey that included demographic and professional characteristics.

Patients were eligible if they had a biopsy-proven solid tumor, were age 18 years or older, and spoke English or Spanish. They provided written consent. Hospice patients were excluded. Accompanying family members, lay caregivers, or companions provided verbal consent. Patients completed baseline surveys including demographic characteristics and health literacy.13,14

Data Collection

An audio recorder was placed in the clinic room by a study coordinator at the beginning of the visit and it recorded throughout; the clinician or patient could stop recording at any time. Data were collected between May 3, 2012, and September 23, 2014. Recorders were kept in a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–approved locked container and transferred via restricted access servers or encrypted universal serial bus drives. Professional interpreters translated Spanish transcripts into English.

Qualitative Analysis

Trained study staff screened and time stamped all 529 individual patient recordings for discussions of financial issues. Any ambiguity in what constituted an instance of financial issue discussion was resolved in consultation with the principal investigator (J.C.T.). A coinvestigator (R.W.) listened to all patient recordings flagged for cost/financial issues. Each cost conversation/transcript represents a unique patient. Any mention of cost-related aspects in transcripts was considered a cost conversation, whether the conversation was consecutive or intermittent in the transcript. Total time of a cost conversation was the cumulative time focused on cost during the entire recording.

Qualitative content analysis and descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics and conversation content. Three investigators (R.W., C.C.K., J.C.T.) independently read a randomly selected subset of 15 transcripts (five from each site) to identify preliminary themes. Candidate themes were compared and revised in person to achieve consensus and were used to create a preliminary codebook. Two investigators (R.W., C.C.K.) then independently read and coded all the transcripts to identify main themes as well as key structural features of the conversations. For each recording, we identified who initiated the cost conversation (defined as the person who explicitly stated any cost-related issue), how long the conversation lasted, and whether the issue was addressed by the clinician (defined as verbal acknowledgment of the issue). Analysis occurred by iterative discussions and summary memos during coding. All codes were compared, and consensus was achieved. New themes were added to the codebook until saturation.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics of counts and frequencies for categorical data and means and standard deviations for continuous data. Clinician characteristics were compared by the percentage of encounters where cost was discussed (< 25%, 25% to 49%, and ≥ 50%). To test for differences in frequency with which cost was discussed among groups, we used the χ2 test, unless counts were less than five, in which case Fisher’s exact test was used. For continuous outcomes, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test. All analyses were conducted in SAS software (version 9.4; Cary, NC), and tests were two sided. P values less than .05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

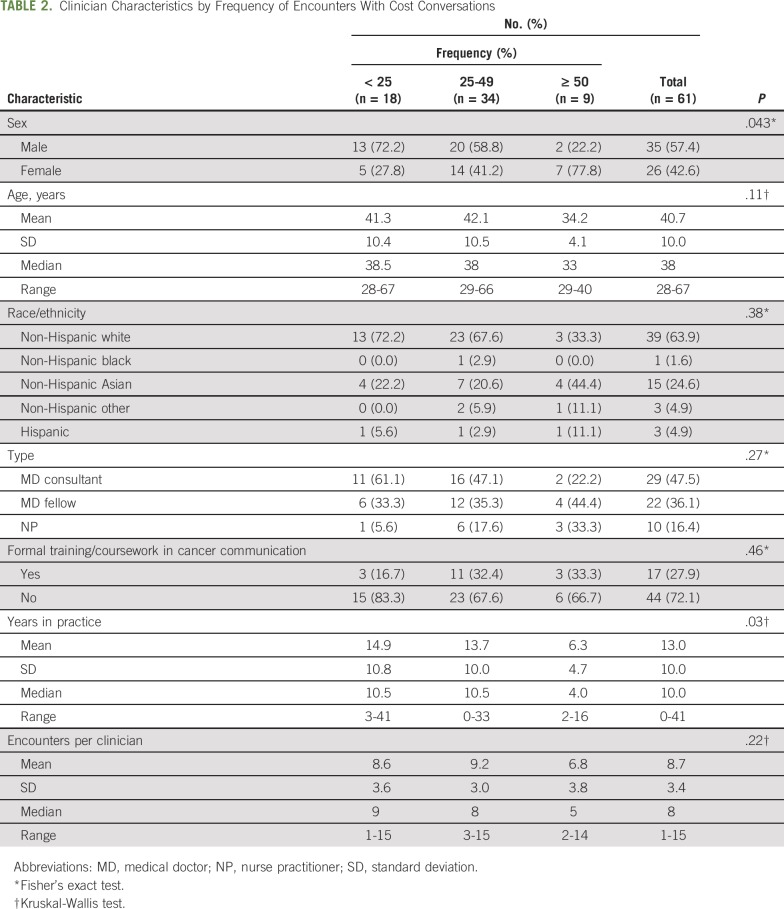

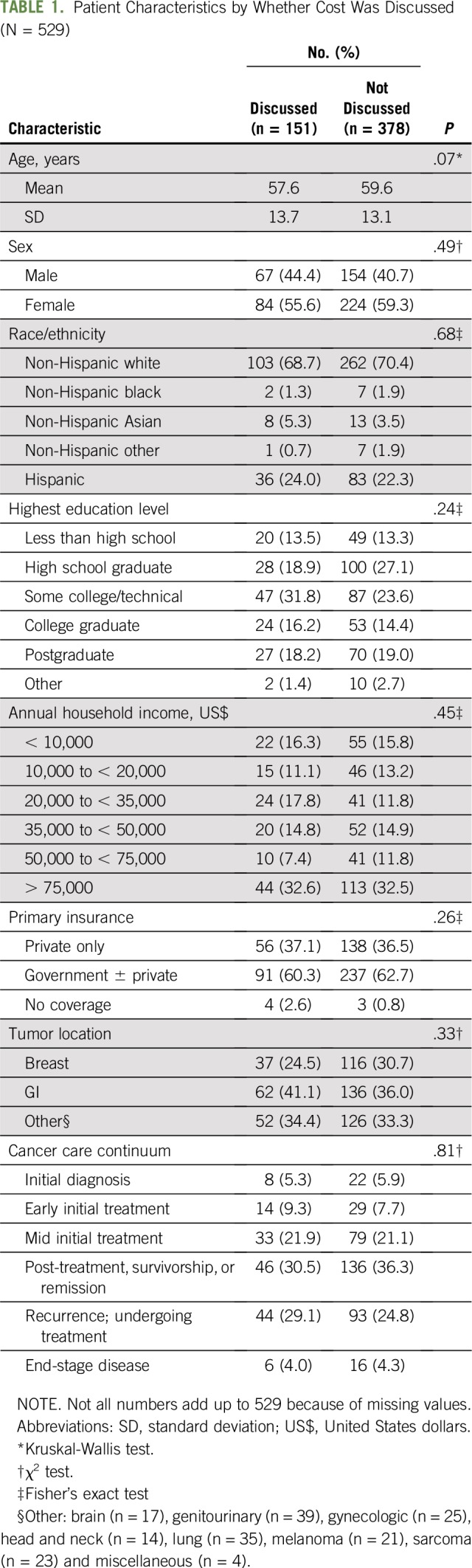

Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Mean age of patients who raised cost issues was 60 years (range, 22 to 93 years); a majority were female (58%) and non-Hispanic white (69%). There were no significant differences in sex, race, ethnicity, tumor location, cancer care continuum, income, education, or insurance type for patients who did or did not raise cost issues. Clinician characteristics are listed in Table 2. Clinical encounters that included cost conversations were significantly different by sex (P = .043), occurring with 27% (seven of 26) of female clinicians versus only 6% (two of 35) for male clinicians. Clinicians who discussed cost in at least 50% of their encounters also had fewer years in practice (P = .03).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics by Whether Cost Was Discussed (N = 529)

TABLE 2.

Clinician Characteristics by Frequency of Encounters With Cost Conversations

Cost Conversation Characteristics

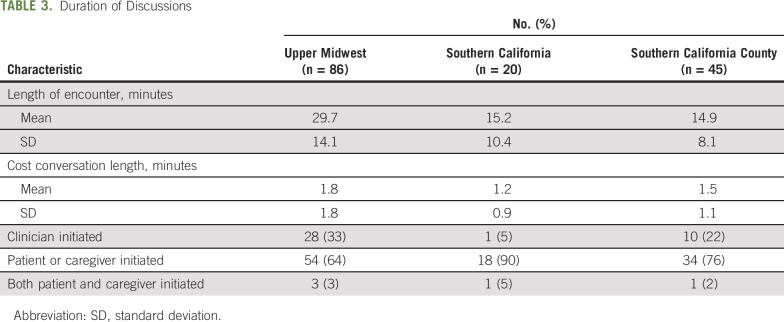

Among the 529 audio recordings, there were 151 (28%) unique patient encounters containing some mention of cost-related issues. There were 86 (26.3%) of 327 instances at the Upper Midwest site, 20 (26.7%) of 75 at the Southern California University site, and 45 (35.4%) of 127 at the Southern California county site. Mean duration of any cost discussion was shorter than 2 minutes (Table 3). Cost issues were raised by patient or caregiver/companion 70% of the time (106 of 151) and by clinician 25% of the time (39 of 151); both clinician and patient raised cost in the same encounter 5% of the time (six of 151) regarding two different cost-related issues. When an issue was raised, it was verbally acknowledged by the clinician 60% of the time. A specific action to address the cost issue was mentioned in 25% of instances. Six of the 151 conversations resulted in social worker referral.

TABLE 3.

Duration of Discussions

Conversation Themes

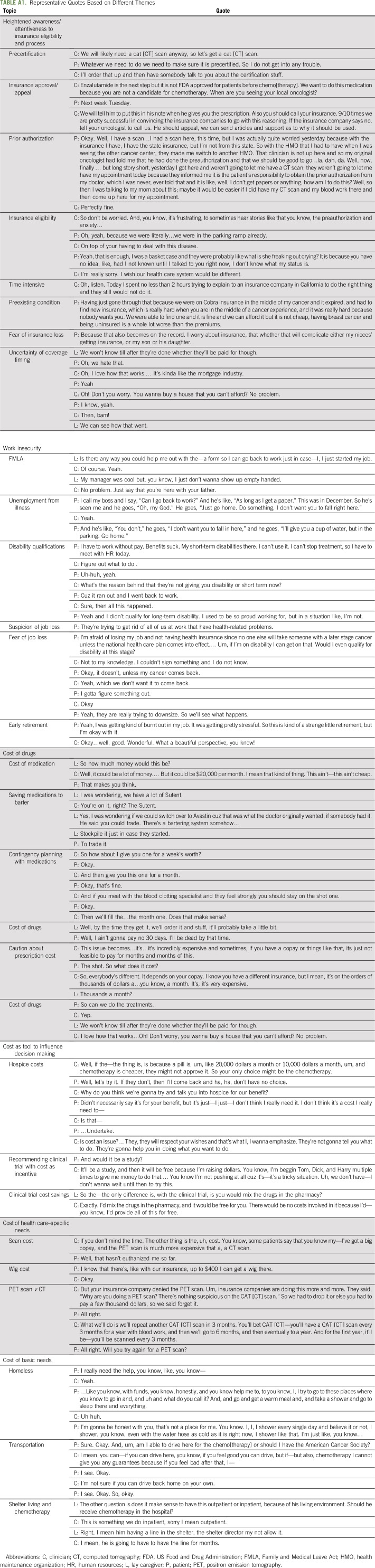

We identified six overarching themes that emerged from analyzing transcripts containing cost conversations: attentiveness to insurance eligibility/coverage; work concerns and employment issues; cost of drugs; cost as a tool to influence decision making; cost of specific tests, visits, or equipment; and social determinants of health.

Here we illustrate these overlapping themes with excerpts from transcripts (C, P, and L represent clinician, patient, and lay caregiver, respectively). Additional excerpts highlighting these themes are listed in Appendix Table A1 (online only).

Attentiveness to insurance eligibility/coverage.

Patients and caregivers were attuned to and concerned about insurance eligibility and how it would affect their care options, often developing insurance expertise they would use to inform their clinicians. Pertinent topics included insurance approval, anticipated denials, and appeal writing to minimize treatment delays. Insurance complexities were entangled with emotional distress and frustration.

C: So don’t be worried. And, you know, it’s frustrating, to sometimes hear stories like that you know, the preauthorization and anxiety…

P: Yeah, that is enough, I was a basket case and [insurance provider] were probably like “what is she freaking out, crying?”

C: I’m really sorry. I wish our health care system would be different.

For many, the payers influenced the timing and number of clinician visits and test ordering or treatment regimens.

P: Yesterday I got here and [state health maintenance organization] weren’t going to let me have a CT [computed tomography] scan; they weren’t going to let me have my appointment today because they informed me it is the patient’s responsibility to obtain the prior authorization from my doctor.

Given the obscurity of associated costs, a frequent but peculiar practice involved sending a so-called test order as a technique to figure out cost and/or coverage for a given intervention being contemplated. If that test resulted in a prohibitive price tag (discoverable only after it had been ordered), they might repeat with a different intervention order or appeal the original test ordered with telephone calls or letters. This form of workaround to ascertain the out-of-pocket cost of a test was common.

Work concerns and employment issues.

Work concerns included current employability (not being able to perform one’s current work), early termination, work restriction/accommodation, ability to get time off for medical visits, timing of disability application, and fears regarding future employability (not being able to obtain future work when healthy). Younger patients expressed suspicions of employers’ terminating workers with high health care costs or those viewed as a liability in the workplace.

P: They’re trying to get rid of all of us at work that have health-related problems.

A preponderance of conversation excerpts in this theme focused on assuring that paperwork was signed or disability eligibility considerations were addressed. Because of the US insurance system, work security concerns were enmeshed with fears of losing insurance coverage altogether.

P: I’m afraid of losing my job and not having health insurance since no one else (insurance company) will take someone with a later stage cancer unless the national health care plan comes into effect. Um if I’m on disability. Would I even qualify for disability at this stage?

Discussion about medical leave also precipitated conversations about retirement or disability. Early retirement was common but not necessarily viewed negatively, because some patients welcomed the opportunity to have more time to spend with loved ones and coordinate their care, notwithstanding the untimely and tragic circumstances.

P: Yeah, I was getting kind of burnt out in my job. It was getting pretty stressful. So this is kind of a strange little retirement, but I’m okay with it.

Cost of drugs.

Costs of cancer drugs, supportive care medications, and even over-the-counter medications posed challenges. Patients and clinicians discussed high costs, copays, and unpredictable coverage. When cost of drugs was raised by clinicians, it was frequently done to caution patients about the potential copays or delays in obtaining treatment. Clinicians frequently encouraged patients to contact their insurance providers before filling the prescriptions to find out how much it would affect them.

C: This issue becomes…it’s…it’s incredibly expensive and sometimes, if you have a copay or things like that, it’s just not feasible to pay for months and months of this.

P: The shot. So what does it cost?

C: So, everybody’s different. It depends on your copay.

Similar to ordering tests or other interventions, there was a general sense of frustration on the part of the clinicians about the obscurity of medication costs and coverage information. In one instance with an anticoagulant, two so-called test prescriptions for low molecular weight heparin were given, along with one test prescription for warfarin, to see which was affordable. These workarounds involving multiple prescriptions for medications and elaborate contingency planning for treatment recommendations on the basis of cost information were commonly used to address issues (if they were addressed), potentially causing confusion for patients.

Patients displayed a spectrum of reactions to the cost of medications, from not wanting to hear the cost, because that would put a price tag on their life, to wanting to limit the number of pills filled at the pharmacy to avoid paying for unused medications.

P: Well, I ain’t gonna pay no 30 days if I’ll be dead by that time.

One patient rationed and stockpiled targeted chemotherapeutic agents in hopes of bartering them for other drugs. Patients frequently asked for less than a 30-day supply, especially with as-needed supportive medications, to get by on the minimum required.

Cost used as a tool to influence decision making.

Clinicians used cost of cancer treatments as a negotiating tool (ie, a means to convince patients of recommendations). For instance, when a clinician thought cheaper chemotherapy was better than newer targeted agents, the price tag helped persuade patients.

C: The thing is, is because a pill is, um, like $20,000 a month or $10,000 a month, um, and chemotherapy is cheaper, they might not approve it. So your only choice might be the chemotherapy.

P: Well, let’s try it.

Clinical trials and research participation were also recommended as cost-saving mechanisms for patients. It would be a win-win to obtain treatment that was otherwise unavailable and generally at no additional cost for the experimental regimen.

P: And would it be a study?

C: It’ll be a study, and then it will be free because I’m raising dollars. You know, I’m beggin’ Tom, Dick, and Harry multiple times to give me money to do that.

Clinicians also invoked cost to discuss hospice, because medications, hospitalizations, and support could be covered, generally be at little or no additional expense (Appendix Table A1).

Cost of specific cancer treatment–related interventions.

It was common to have specific interventions or even the cost of parking be discussed. There were times when patients would become emotional about the cost of imaging or why computed tomography was performed instead of positron emission tomography/computed tomography, fearing that they were undergoing an inferior scan because of the expense associated with the positron emission tomography, which insurance would sometimes refuse to cover.

C: The other thing is the, uh, cost. You know, some patients say that you know my—I’ve got a big copay, and the PET [positron emission tomography] scan is much more expensive than a, a CT [computed tomography] scan.

P: Well, that hasn’t killed me so far.

In this quote the clinician seems to be delicately approaching the out-of-pocket cost associated with an intervention, hypothetically to gauge the patient’s reaction. Concern regarding health care costs was not limited to scans; laboratory testing, consultations, parking, handicap stickers, and medical devices were all mentioned. Cranial prostheses (wigs) were frequently discussed, as were the associated expenses. Even with insurance subsidizing wigs through prescription, the cost of wigs could be prohibitive. Patients also commonly mentioned avoiding certain additional consultative services like genetic counseling, dieticians, and physical therapy/rehabilitation because of the associated expenses.

Social determinants of health.

The most challenging situations we observed occurred when essential costs of basic needs (food, shelter, and clothing) were mentioned. When patients were uninsured and already struggling to meet the most basic needs, a cancer diagnosis was even more devastating. For instance, one young man struggling to find a place to sleep or even shower who underwent emergent lifesaving surgery subsequently received a bill he felt was impossible to pay. Homeless patients obtaining chemotherapy through Medicaid still need to pay for supportive care. Other complexities related to basic needs include questions like whether a peripheral catheter is feasible in a shelter.

P: I really need the help, you know…

C: Yeah.

P: …like you know, with funds, you know, honestly, and you know help me to, to you know, I, I try to go to these places where you know to go in and, and uh and what do you call it? And, and go and get a warm meal and, and take a shower and go to sleep there and everything.

These conversations were associated with the most emotional distress.

DISCUSSION

In this study, clinicians and patients described in their own words how they navigate financial matters. We found that cost discussions were not infrequent; the issue of cost was most often raised by patients/caregivers, but it often went unaddressed when raised. The average duration of a cost conversation was brief. Patients who brought up cost were similar to the entire cohort, suggesting the likely ubiquity of financial concerns. Clinicians who did bring up cost were more likely to be female and have fewer years in practice. Cost conversations that did occur demonstrated attentiveness to insurance eligibility processes, work security and employment issues, cost of medications or health care specifics, influence on decision making or a clinical care plan, and threats to basic needs.

Discussing money or any socioeconomic constraint on care is rarely easy for clinicians, especially while simultaneously trying to address clinical challenges. Balancing the emotions of the patient and family/caregiver can be difficult and require care and skill. However, the cost of cancer care is a topic that seems unavoidable in contemporary oncology practice. This may explain why younger clinicians were more likely to discuss these topics, because the current health care climate is inextricably linked to finances. Similar to our study, the study by Hunter et al15 assessed cost conversations in 677 breast cancer clinic visits with physicians and found cost was mentioned in one in five clinic visits; these conversations were short, lasting less than 1 minute, and focused on cost-reducing strategies. However, in contrast to that study, we found that clinicians raised cost issues much less commonly than patients (30% v 59% in the Hunter et al15 study). In addition, providers were less likely to address cost-related issues (only 25% of the time v nearly 40% in the Hunter et al15 study). This discordance could be a result of some important differences between our study and that by Hunter et al.15 Our study occurred predominantly at academic sites, included all cancer types, had a higher rate of uninsured patients (3.2% v 0.004% in the Hunter et al15 study), and included advanced-practice provider visits in addition to physician visits. Moreover, our study goes into depth to characterize the content of discussions between patients with cancer, caregivers, and providers; our study also included patients with multiple tumor types, making it relevant for patients with cancer in general. Other single-center studies have demonstrated financial issues are broached between 14% and 58% of the time.6-8 In contrast, patient opinion studies have suggested that patients want cost to be included in oncology visits more (52% to 96%).6,7,16-18 Therefore, there seems to be a disconnect between oncologists’ desire to address cost, patient expectations, and actual occurrence of these discussions.

Our data demonstrate significant concern across care contexts and clinical populations about the impact of a cancer diagnosis on overall financial stability and socioeconomic well-being of patients and families. How to afford care manifests as several financial issues in conversations. Emotional distress associated with these concerns was frequently evident.

Most clinicians feel they have some responsibility in discussing and containing costs of care.19,20 Although generally sympathetic, clinicians frequently did not take direct action in response. Clinicians addressed cost if it directly influenced their decision making or played into their persuasive strategy (eg, clinical trial recruitment or therapy choice). There seems to be an intricate and delicate game that occurs when clinicians address financial matters, creating workarounds to address patient needs. There were several instances when insurance coverage was unknown for an intervention, and a variety of scenarios played out to determine coverage. Although issues were only acted upon 25% of the time, the most common way to address or preempt cost issues was contingency planning, either with a multiple parallel plans approach or via sequential so-called test orders. This shows there is dedication to mitigating financial issues when direction of clinical management is affected. The exhausting clinical burden of this type of contingency care planning needs to be acknowledged and could adversely influence adherence and treatment response. Our data support a growing concern that barriers exist for patients and clinicians robustly and routinely engaging in conversations about financial matters in cancer care that result in concrete help.

Barriers may include lack of time, lack of training on the topic, and unknown strategies to address financial issues if asked. In our study, when financial issues were raised, direct action was taken in only 25% of cases, and 40% of the time, no verbal acknowledgment was given. Good communication and reflexive listening where patients are acknowledged and validated are simple but powerful strategies to help validate financial concerns and be supportive of patients’ struggles even when a resolution is not offered. Evidence in physician and patient communication supports this strategy, as do our recordings.21,22 Clinicians must be aware of the general costs of care that they prescribe to prepare patients for potential out-of-pocket expenses.22 Verbal support and validation without action by clinicians suggests discomfort or unfamiliarity with resources to address concerns, as has been similarly reported in other studies.6,23 It is also possible that clinicians may have a fundamental issue with how to appropriately manage fiduciary responsibility toward patients’ best interests and take into consideration the cost of care.24 Communication skills can be improved and empower clinicians to address an array of psychosocial behaviors.25 Therefore, ASCO has released a guideline on the cost of cancer care, intended to help physicians navigate these complex and intricate discussions.26,27 Additional recommendations to address financial concerns from the literature and our audio recordings include referral to social services, which can help patients with counseling and coping strategies as well as benefits assessment for insurance and disability paperwork, pharmacy consultations to manage medications and drug interactions and find equivalent generics, and referral to patient navigators, such as the American Cancer Society, which can help identify resources to support patients, including grants and funding that can be used to mitigate costs.22,28,29 There has also been increased focus on and recognition of the challenge of cancer care financially for patients and society in the last 5 years. Recently, there have been several societal developments to help clinicians address the cost of cancer care, such as the ASCO Value Framework, which provides the relative value of various cancer treatments compared with clinical trial data; the NCCN evidence blocks, which include consideration of cost in treatment choices; and the Choosing Wisely campaigns, which recommend ways to minimize waste in various specialties, including hematology and oncology.11,25,26 These campaigns highlight the increasing attention on addressing the cost of cancer care and supporting clinicians who undoubtedly are involved in helping patients navigate these situations but may not be best equipped to tackle them. Moreover, physicians may not be the ideal people to mitigate costs; there is evidence that use of financial navigators can help patients manage out-of-pocket expenses.29,30 There is opportunity for continued improvement in tackling financial costs in cancer care, and multiple stakeholders in addition to physicians will be necessary to adequately address this issue.

This multicenter study with a large number of observations nevertheless has limitations. The recorded conversations in this study were completed by September 23, 2014. It is possible that some aspects of cost conversations between patients and clinicians have changed since our data collection. However, examining temporal changes in how conversations occur, particularly in the wake of emerging policy discussions, could shed additional light on how those policy initiatives are playing out in practice. Our conversations were limited to those between a patient and his or her clinician. We did not capture duration of patients’ treatment or any conversations between patients and financial counselors, pharmacists, or social workers. Analysis was performed independently and in duplicate and included a content expert and a clinician noncontent expert to increase trustworthiness of our inferences; however, qualitative analyses are not generalizable to an entire population. Moreover, although our sample included 25% Hispanic/Latino participants, African Americans or Asians comprised less than 10% of patients. Different demographic subgroups may face different financial barriers. In addition, we did not capture nonverbal communication behaviors. Last, we captured one clinic visit per patient; cost issues may have been addressed before or after this visit.

In conclusion, our findings add to a growing body of literature on financial toxicities in oncology and broaden the categories that inform that literature. The frequency with which financial issues were raised and the context of those conversations suggest opportunities to improve discussion of cost in routine oncology practice. High-quality conversations that include cost are essential in choosing treatments, calibrating care to the life of the patient.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by National Institutes of Complementary and Integrative Health Grant No. R01 AT06515 (J.C.T.); the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, Mayo Clinic (R.W., C.C.K.); Grant No. K23 HL128859 from the National Heart Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH; C.C.K.); and by Clinical and Translational Science Award No. UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Appendix

TABLE A1.

Representative Quotes Based on Different Themes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Rahma Warsame, Aminah Jatoi, Jon C. Tilburt

Collection and assembly of data: Rahma Warsame, Ashok Kumbamu, Cara Fernandez, Aminah Jatoi

Data analysis and interpretation: Cassie C. Kennedy, Ashok Kumbamu, Megan Branda, Aaron L. Leppin, Brittany Kimball, Thomas O’Byrne, Aminah Jatoi, Heinz-Josef Lenz, Jon C. Tilburt

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Conversations About Financial Issues in Routine Oncology Practices: A Multicenter Study

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jop/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Heinz-Josef Lenz

Honoraria: Merck Serono, Roche, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck Serono, Roche, Pfizer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Merck Serono, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Roche

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, et al. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levit LA, Balogh EP, Nass SJ, et al (eds): Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dusetzina SB, Winn AN, Abel GA, et al. Cost sharing and adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:306–311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.9123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1143–1152. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schrag D, Hanger M. Medical oncologists’ views on communicating with patients about chemotherapy costs: A pilot survey. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:233–237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altomare I, Irwin B, Zafar SY, et al. Physician experience and attitudes toward addressing the cost of cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:e281–e288, 247-248. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.007401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly RJ, Forde PM, Elnahal SM, et al. Patients and physicians can discuss costs of cancer treatment in the clinic. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:308–312. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.003780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zafar SY, Chino F, Ubel PA, et al. The utility of cost discussions between patients with cancer and oncologists. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shields AL, Hao Y, Krohe M, et al: Patient-reported outcomes in oncology drug labeling in the United States : A framework for navigating early challenges. Am Health Drug Benefits 9:188-197, 2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Schnipper LE. ASCO task force on the cost of cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5:218–219. doi: 10.1200/JOP.091023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0177. National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Evidence Blocks. https://www.nccn.org/evidenceblocks/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimball BC, James KM, Yost KJ, et al. Listening in on difficult conversations: An observational, multi-center investigation of real-time conversations in medical oncology. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:455. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyer N, Sorra JS, Smith SA, et al. Psychometric properties of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) Clinician and Group Adult Visit Survey. Med Care. 2012;50(suppl):S28–S34. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31826cbc0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.01.016. Locke DEC, Decker PA, Sloan JA, et al: Validation of single-item linear analog scale assessment of quality of life in neuro-oncology patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 34:628-638, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hunter WG, Zafar SY, Hesson A, et al: Discussing health care expenses in the oncology clinic: Analysis of cost conversations in outpatient encounters. J Oncol Pract 13:e944-e956, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, et al. Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:162–167. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaser E, Shaw J, Marven M, et al. Communication about high-cost drugs in oncology: The patient view. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1910–1914. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meisenberg BR, Varner A, Ellis E, et al. Patient attitudes regarding the cost of illness in cancer care. Oncologist. 2015;20:1199–1204. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tilburt JC, Wynia MK, Sheeler RD, et al. Views of US physicians about controlling health care costs. JAMA. 2013;310:380–388. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel MR, Shah KS, Shallcross ML. A qualitative study of physician perspectives of cost-related communication and patients’ financial burden with managing chronic disease. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:518. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1189-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranjan P, Kumari A, Chakrawarty A. How can doctors improve their communication skills? J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:JE01–JE04. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/12072.5712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zafar SY, Newcomer LN, McCarthy J, et al. How should we intervene on the financial toxicity of cancer care? One shot, four perspectives. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:35–39. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_174893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berry SR, Bell CM, Ubel PA, et al. Continental divide? The attitudes of US and Canadian oncologists on the costs, cost-effectiveness, and health policies associated with new cancer drugs. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4149–4153. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Kort SJ, Kenny N, van Dijk P, et al. Cost issues in new disease-modifying treatments for advanced cancer: In-depth interviews with physicians. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:1983–1989. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilligan T, Coyle N, Frankel RM, et al. Patient-clinician communication: American Society of Clinical Oncology consensus guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3618–3632. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: The cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3868–3874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al. Updating the American Society of Clinical Oncology Value Framework: Revisions and reflections in response to comments received. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2925–2934. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kopolovic I, Conter HJ, Hicks LK: ‘Choosing Wisely’ campaigns from ASCO and ASH: A review for clinicians in hematology and oncology. https://www.gotoper.com/publications/ajho/2015/2015dec/choosing-wisely-campaigns-from-asco-and-ash-a-review-for-clinicians-in-haematology-and-oncology.

- 29.Simon S. Patient navigators help cancer patients manage care. https://www.cancer.org/latest-news/navigators-help-cancer-patients-manage-their-care.html

- 30.Yezefski T, Steelquist J, Watabayashi K, et al. Impact of trained oncology financial navigators on patient out-of-pocket spending. Am J Manag Care 245 SupplS74–S79.2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]