Abstract

PURPOSE:

Spending for patients with advanced cancer is substantial. Past efforts to characterize this spending usually have not included patients with recurrence (who may differ from those with de novo stage IV disease) or described which services drive spending.

METHODS:

Using SEER-Medicare data from 2008 to 2013, we identified patients with breast, colorectal, and lung cancer with either de novo stage IV or recurrent advanced cancer. Mean spending/patient/month (2012 US dollars) was estimated from 12 months before to 11 months after diagnosis for all services and by the type of service. We describe the absolute difference in mean monthly spending for de novo versus recurrent patients, and we estimate differences after controlling for type of advanced cancer, year of diagnosis, age, sex, comorbidity, and other factors.

RESULTS:

We identified 54,982 patients with advanced cancer. Before diagnosis, mean monthly spending was higher for recurrent patients (absolute difference: breast, $1,412; colorectal, $3,002; lung, $2,805; all P < .001), whereas after the diagnosis, it was higher for de novo patients (absolute difference: breast, $2,443; colorectal, $4,844; lung, $2,356; all P < .001). Spending differences were driven by inpatient, physician, and hospice services. Across the 2-year period around the advanced cancer diagnosis, adjusted mean monthly spending was higher for de novo versus recurrent patients (spending ratio: breast, 2.39 [95% CI, 2.05 to 2.77]; colorectal, 2.64 [95% CI, 2.31 to 3.01]; lung, 1.46 [95% CI, 1.30 to 1.65]).

CONCLUSION:

Spending for de novo cancer was greater than spending for recurrent advanced cancer. Understanding the patterns and drivers of spending is necessary to design alternative payment models and to improve value.

INTRODUCTION

Much of the suffering and nearly all the mortality caused by cancer is attributable to advanced disease. Advanced disease develops in one of two ways: patients with de novo stage IV cancer have metastatic disease when their cancer is first diagnosed, and recurrent patients develop metastatic disease after treatment of a previously diagnosed localized (ie, stage I to III) cancer. For some cancer types, recurrence is more common than de novo metastatic disease (eg, breast cancer), whereas for others, de novo metastatic disease is more common (eg, lung cancer). Previously, we described differences in the treatments provided to and mortality experienced by patients with recurrent and de novo metastatic disease.1 Recurrent patients were less likely to receive chemotherapy and radiation compared with de novo patients. Patients with breast cancer with recurrence experienced inferior survival compared with de novo patients, whereas patients with lung and colorectal cancer with recurrence experienced similar survival compared with de novo patients.

Cost is another major burden associated with advanced disease.2-4 Studies have suggested that spending during the initial phase of care is greater for patients with stage IV versus localized disease.5-7 However, previous efforts to characterize spending for advanced cancer often have been limited because they focused predominately on patients with de novo metastatic disease (largely because of the lack of recurrence status data in most tumor registries).8-10 Although a few studies have generated spending estimates for breast cancer recurrence,11-15 we still know comparatively little about spending for recurrent metastatic disease. In addition, previous studies often have not analyzed spending across the entire episode of care. Patients with recurrent cancer may incur substantial costs for treatment/surveillance of the primary localized cancer.16-20 Spending for these services, which occur before the advanced cancer diagnosis, affect lifetime cancer spending estimates and could affect advanced disease spending estimates.

To explore whether spending for recurrent and de novo advanced cancer differ meaningfully, we recently studied 7,112 adults with advanced breast, colorectal, and lung cancer treated in three Kaiser Permanente regions. We found higher spending for recurrent patients before the advanced cancer diagnosis and higher spending for de novo patients after the advanced cancer diagnosis.21 Still, important questions remain with regard to advanced cancer spending, including spending patterns in the fee-for-service setting and the impact of various service types on spending differences. To evaluate spending across the entire initial care episode for advanced cancer, we compared mean monthly total and service-specific health care costs for a population-based sample of Medicare patients with breast, lung, or colorectal cancer who had either recurrent disease after prior treatment of a stage I to III cancer or de novo stage IV metastatic disease.

METHODS

Cohort Derivation

Using the linked SEER-Medicare claims database, we identified patients diagnosed with a primary breast, colorectal, or lung cancer.22 All patients had to be continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B, with no enrollment in a health maintenance organization, from the initial cancer diagnosis through the end of follow-up (the earlier of death, subsequent new primary cancer, or end of study [December 31, 2012]). Patients were excluded if the cancer diagnosis came from a death certificate, stage was 0/unknown, age at diagnosis was younger than 65 years, there was a previous history or cancer, Medicare eligibility was based on permanent disability/end-stage renal disease, or there were no Medicare claims from diagnosis through the end of follow-up. Part D enrollment was not required.

From this cohort, we identified two types of patients with advanced cancer: patients with de novo advanced cancer diagnosed with stage IV disease between 2008 and 2011 and patients with recurrent advanced cancer diagnosed with stage I to III disease (excluding stage IIIb lung cancer because of their high probability for having micrometastatic disease) between 1998 and 2011, treated with definitive local therapy (ie, surgery for all cancers except stage IIIa lung cancer where combined chemotherapy/radiation therapy was required) within 1 year of their initial cancer diagnosis, and who subsequently developed recurrence between 2008 and 2011 (the same time range used for de novo diagnoses).23 Recurrence status was determined using Medicare claims and our previously validated recurrence detection algorithms (area under the curve for recurrence detection, 0.924 to 0.953; median absolute error for recurrence timing, 2.1 to 5.5 months).10,24 After the advanced cancer diagnosis date was determined, patients who were not continuously enrolled in Medicare for at least 12 months before that date were excluded. Patients who died less than 30 days after their advanced cancer diagnosis also were excluded.

Variable Derivations and Definitions

SEER files provided cancer features (eg, stage) and patient attributes (eg, sex). Claims during the 12 months preceding the advanced cancer diagnosis were used to derive a comorbidity score, excluding cancer diagnoses.25-27 Claims also were used to identify receipt of chemotherapy (including cytotoxic, biologic, and oral agents) and radiation therapy.28 For patients who developed recurrence, cancer-directed therapy for the initial stage I to III diagnosis would have occurred before recurrence. Thus, cancer-directed therapy was recorded both before and after the advanced cancer diagnosis and categorized on basis of time relative to the advanced cancer diagnosis. Among patients with de novo advanced disease, cancer therapy was only recorded after the initial cancer diagnoses. Hospitalizations and death were recorded during the 24-month period around the advanced cancer diagnosis.

The primary outcome was mean total monthly Medicare charges for all services provided. We calculated spending estimates for the 12-month period before (ie, from month −12 to month −1) and after (ie, from month 0 to month 11) the advanced cancer diagnosis. We also calculated monthly spending during the 24-month period surrounding (ie, from 12 months before to 11 months after) the advanced cancer diagnosis. Secondary outcomes included spending by Medicare file type, as follows: inpatient hospital and skilled nursing (Medicare Provider Analysis and Review), provider (National Claims History), outpatient (Outpatient Standard Analytical File), hospice, home health, durable medical equipment, and prescriptions (for patients enrolled in Part D). We included all spending that occurred before or within the month of death. Crude mean monthly spending estimates excluded patients who died in a previous month. Spending values were reported as 2012 US dollars.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed separately for each cancer type. Mean monthly spending over time was plotted for all medical services as well as by type of service and by time from initial diagnosis to advanced disease (< 1, 1 to 2, > 2 to 4, or > 4 years). We analyzed differences in unadjusted monthly spending between patients with recurrent and de novo advanced cancer during the year before and the year after the advanced cancer diagnosis using a permutation test. To estimate differences in total mean monthly spending across the 24-month observation period while controlling for other factors, we used multivariable linear regression to derive adjusted spending ratios (SRs). Model covariates were age, sex, race, ethnicity, income, marital status, comorbidity, year of advanced cancer diagnosis, type of advanced cancer (de novo or recurrent), month relative to the advanced cancer diagnosis, and month of death. To adjust for temporal differences in spending across the 24-month observation period, the model included an interaction term for advanced cancer type × month relative to advanced cancer diagnosis. There were multiple monthly spending estimates per patient, so general estimating equations were used to adjust for repeated measures. Log transformation of costs resulted in a reasonably approximate normal distribution, so log-transformed monthly cost was the dependent variable in these models. Some patients died during the 12-month period after the advanced cancer diagnosis, so monthly spending estimates during this period were adjusted on the basis of a patient’s inverse probability of survival at the end of follow-up (using a logistic regression model that included selected variables listed in Appendix Table A1, online only).29

In a secondary analysis, we sought to describe the impact of hospitalization and chemotherapy on total monthly spending while controlling for other factors. To this end, we modified the primary model to indicate whether the patient was hospitalized or received chemotherapy during each month. After estimating monthly spending for the conditions of receiving and not receiving chemotherapy, we calculated the difference between these two values to derive the average increase in monthly spending associated with chemotherapy. The same method was applied to hospitalizations. All tests of statistical significance were two-sided. The institutional review board from the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center provided oversight for this project.

RESULTS

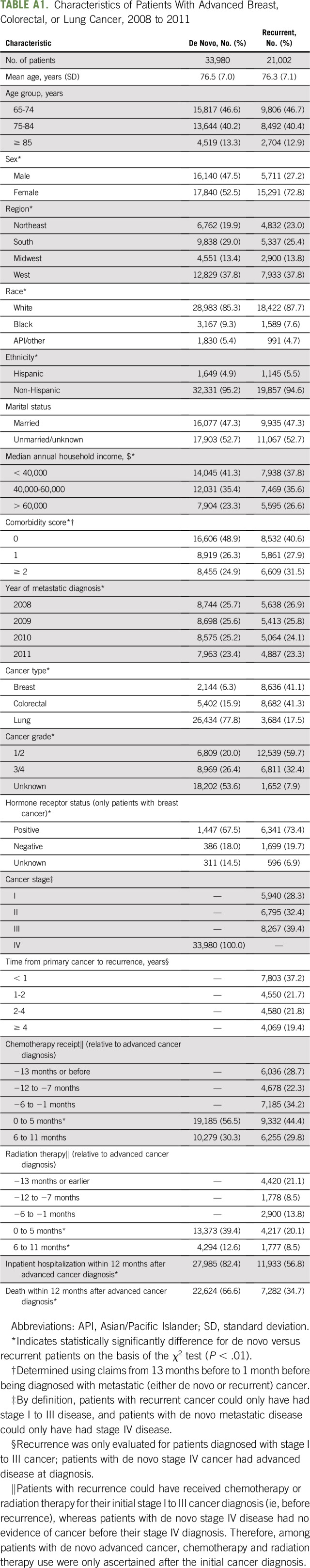

We identified 54,982 patients 65 years of age or older who developed advanced breast, colorectal, or lung cancer between 2008 and 2011. The proportion having recurrent disease varied by cancer type (80% breast, 62% colorectal, 12% lung, 38% overall; P < .01; Appendix Table A1). The mean age was 76 years. Blacks represented a significantly greater proportion of patients with de novo versus recurrent advanced cancer (9.3% v 7.6%; P < .01), as did those who had an annual income of less than $40,000 (41.3% v 37.8%; P < .01). Among those for whom grade was known, having grade 3/4 disease was more common among de novo versus recurrent patients (57% v 35%; P < .01). Hospitalization, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and death were all more common after a de novo versus recurrent advanced cancer diagnosis.

Plots and estimates of unadjusted total mean monthly spending (Figs 1-3; Table 1) demonstrate several consistent patterns across all three cancer types. Before the advanced cancer diagnosis, spending was significantly higher among patients with recurrent versus de novo advanced disease (P < .001). These differences persisted whether we analyzed recurrences that occurred less than or more than 1 year after the initial cancer diagnosis (data not shown). At the time of the advanced cancer diagnosis, spending for de novo patients peaked at a higher amount than for recurrent patients. This peridiagnosis spending peak predominantly was due to inpatient spending and was largest for patients with colorectal cancer. After the advanced cancer diagnosis, spending for de novo patients was significantly higher than for recurrent patients (P < .001). Finally, comparison of patients with de novo and recurrent cancer showed that monthly spending estimates for most categories of medical service before and after the advanced cancer diagnosis were statistically significantly different.

Fig 1.

Unadjusted mean per-patient per-month spending for all Medicare fee-for-service files from 1 year before to 1 year after an advanced breast cancer diagnosis for patients with de novo stage IV (red) versus recurrent (blue) advanced disease. (A) Total spending. (B) Inpatient (Medicare provider analysis and review) spending. (C) Physician (national claims history) spending. (D) Outpatient (Outpatient standard analytic file) spending. Spending estimates reflect constant 2012 US dollars. Statistical comparisons of spending for de novo versus recurrent patients are presented in Table 2.

Fig 3.

Unadjusted mean per-patient per-month spending for all Medicare fee-for-service files from 1 year before to 1 year after an advanced lung cancer diagnosis for patients with de novo stage IV (red) versus recurrent (blue) advanced disease. (A) Total spending. (B) Inpatient (Medicare provider analysis and review) spending. (C) Physician (national claims history) spending. (D) Outpatient (outpatient standard analytic file) spending. Spending estimates reflect constant 2012 US dollars. Statistical comparisons of spending for de novo versus recurrent patients are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Mean Monthly Spending (Unadjusted) for Patients With De Novo and Recurrent Advanced Cancer During the Year Before and the Year After the Advanced Cancer Diagnosis by Medicare File Type in 2012 US Dollars

We stratified spending by Medicare file type to describe how patterns of spending differed for patients with de novo versus recurrent cancer and to explore which types of services were responsible for spending throughout the 24-month observation period (Figs 1, 2 and 3; Table 1). Inpatient services accounted for the largest share of spending before and after the advanced cancer diagnosis, except for patients with recurrent breast cancer. Provider and outpatient spending was significantly higher for recurrent patients before the advanced cancer diagnosis and for de novo patients after the advanced cancer diagnosis (P < .001). Although inpatient services accounted for the largest absolute increase in spending after versus before an advanced cancer diagnosis, hospice services were responsible for the largest relative increase in spending over time.

Fig 2.

Unadjusted mean per-patient per-month spending for all Medicare fee-for-service files from 1 year before to 1 year after an advanced colorectal cancer diagnosis for patients with de novo stage IV (red) versus recurrent (blue) advanced disease. (A) Total spending. (B) Inpatient (Medicare provider analysis and review) spending. (C) Physician (national claims history) spending. (D) Outpatient (outpatient standard analytic file) spending. Spending estimates reflect constant 2012 US dollars. Statistical comparisons of spending for de novo versus recurrent patients are presented in Table 2.

Multivariable analysis showed that comorbidity was associated with the largest increase in spending across all cancer types (Table 2). Compared with patients with recurrent advanced disease, those with de novo metastatic cancer had significantly higher monthly spending for breast (SR, 2.4; 95% CI, 2.05 to 2.77; P < .001), colorectal (SR, 2.6; 95% CI, 2.31 to 3.01; P < .001), and lung (SR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.30 to 1.65; P < .001) cancer. Other factors associated with significantly greater monthly spending among patients with colorectal and lung cancer included being married (v not) and being in the highest (v lowest) income group. In contrast, patients with breast cancer who were married had significantly lower spending. Spending during the last month of life was significantly greater than spending during the preceding months, with the largest impact occurring for breast (SR, 2.7; 95% CI, 2.46 to 2.85; P < .001) followed by colorectal (SR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.49 to 1.70; P < .001) and lung (SR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.24 to 1.34; P < .001) cancer.

TABLE 2.

Ratio of Mean Monthly Spending for Selected Characteristics While Controlling for Other Factors

Chemotherapy receipt was associated with significantly higher total monthly spending for patients with breast (SR, 8.3; 95% CI, 8.01 to 8.70; P < .001), colorectal (SR, 9.1; 95% CI, 8.67 to 9.52; P < .001), and lung (SR, 4.8; 95% CI, 4.62 to 4.93; P < .001) cancer. Hospitalization also was associated with significantly higher monthly spending for patients with breast (SR, 21.7; 95% CI, 20.92 to 22.50; P < .001), colorectal (SR, 23.3; 95% CI, 22.49 to 24.05; P < .001), and lung (SR, 12.4; 95% CI, 12.11 to 12.66; P < .001) cancer. The average increases in total monthly spending associated with chemotherapy and hospitalization were $7,301 and $15,817 for breast, $11,908 and $20,615 for colorectal, and $5,995 and $10,762 for lung, respectively. Even after adding chemotherapy and hospitalization to the model, the spending differential between patients with de novo and recurrent cancer remained significant: breast SR, 1.7 (95% CI, 1.46 to 1.90; P < .001); colorectal SR, 1.5 (95% CI, 1.34 to 1.68; P < .001); and lung SR, 1.2 (95% CI, 1.09 to 1.35; P < .001).

DISCUSSION

Using Medicare fee-for-service claims for a population-based sample of patients with breast, colorectal, and lung cancer, we found substantially greater spending for patients with de novo versus recurrent advanced disease. This difference was largely attributable to higher spending for inpatient, outpatient (including chemotherapy), and physician services during the year after the advanced cancer diagnosis. That said, even when we controlled for hospitalizations, chemotherapy receipt, and other factors, mean monthly spending during the 2-year period surrounding the advanced cancer diagnosis was still 20% to 70% higher for patients with de novo versus recurrent advanced disease.

There could be several reasons for why spending around a de novo advanced cancer diagnosis was greater than spending around a recurrent advanced cancer diagnosis. Many patients with recurrent disease received surgery and/or adjuvant treatment of their initial cancer diagnosis, so they may not have been eligible to receive treatment again when advanced disease developed. In addition, they may have been less inclined to receive aggressive care because they had different treatment goals.30 Among those who did receive therapy, early treatment discontinuation and early cancer-related symptoms may have been more likely because their disease was less responsive to therapy. Alternatively, patients with de novo disease may have had more spending around their advanced cancer diagnosis because they tended to present with symptomatic disease, whereas patients with recurrent disease may have been more likely to present with abnormal surveillance scans and a lower burden of disease.

We analyzed spending during the 24-month period that spanned the advanced cancer diagnosis (ie, 12 months before to 11 months after) for several reasons. First, the monetary impact of an advanced cancer diagnosis extends over many months and may include evaluative services provided before and treatments provided after the advanced cancer diagnosis. Second, the date of the recurrent cancer diagnosis was estimated using claims, so the true advanced cancer diagnosis date may have been a few months before or after the estimated date. Third, studying the 12-month period before the advanced cancer diagnosis allowed us to compare the survivorship phase of care among patients previously treated for stage I to III cancer to the prediagnosis phase of care among patients who developed de novo stage IV advanced cancer.

Not surprisingly, spending patterns differed during the 12 months before versus 12 months after the advanced cancer diagnosis. Before, spending in the recurrent cohort exceeded spending in the de novo cohort. This was due to multiple factors. Among patients who developed recurrence less than 1 year after their initial cancer diagnosis, prerecurrence spending was driven by treatment of the initial localized cancer. Among patients who developed recurrence more than 1 year after their initial cancer diagnosis, prerecurrence spending reflected survivorship care and evaluative services used to help to diagnosis recurrence. Our findings not only confirm previous research that demonstrated higher net costs for cancer survivors31 but also extend the existing knowledge base by describing the impact of cancer recurrence on the survivorship phase of care. (Most previous studies were not able to discriminate between patients diagnosed with stage I to III cancer who did v did not develop recurrent disease.)

After the advanced cancer diagnosis, spending in the de novo cohort exceeded spending in the recurrent cohort. This also was due to multiple factors, particularly hospitalizations, outpatient services (including chemotherapy), and physician services. Of note, lower total spending after the advanced cancer diagnosis in the recurrent cohort did not translate into greater spending for hospice services. In fact, hospice spending was greater for patients with de novo versus recurrent cancer (P < .05). Hospice was responsible for the largest relative increase in spending after versus before the advanced cancer diagnosis, but it still only accounted for a small proportion of total monthly spending in the postdiagnosis period (4.1% to 6.5%; Table 2).

Our findings validate results from previous studies of patients with metastatic disease,11-15,31-33 and our spending estimates were similar to those derived from our previous analysis of data from three capitation-based Kaiser Permanente regions.21 Our results extend the current knowledge base because they were based on a population-based sample of patients with multiple different cancer types, evaluated fee-for-service spending before and after the advanced cancer diagnosis, and described advanced cancer spending by type of service (including hospitalizations and chemotherapy). Our analysis was uniquely able to account for recurrence because it made use of a novel, claims-based recurrence detection tool. Analyses have demonstrated that this tool is highly accurate, but misclassification risk remains.10,24 For example, the algorithm cannot exclude all patients with locoregional recurrence; this could have introduced a downward bias for the recurrence spending estimates among patients with breast cancer. Patients who developed recurrence but did not receive any treatment could have been inappropriately excluded from the recurrence sample. If so, then we may have overestimated total spending for recurrence. Finally, we estimated spending from the payer/health system perspective, so we did not include patients’ potentially substantial out-of-pocket financial liabilities.34

Implications of our study include that historical estimates of spending for advanced disease could overestimate actual spending because they do not account for recurrent disease and historical estimates of spending for the continuing (ie, survivorship) phase of care could overestimate actual spending because they incorrectly include spending for recurrent disease.4,31,35 Our findings highlight the importance of clearly defining starting/stopping points and reimbursement amounts for episode-based payment models. Perhaps recurrence status should be used to identify the end of an initial treatment and the beginning of a recurrent treatment episode and to help to develop fair reimbursement policies for these episodes. For payers who prefer reimbursement models that are based on total cost of care, recurrence could be used to adjust payment amounts and to help to discriminate between high- and low-value spending areas or institutions. The large spike in spending around the time of an advanced cancer diagnosis underscores the importance of assessing financial toxicity and providing social support to patients with advanced cancer. Finally, our findings highlight the need for more research with regard to the goals, preferences, and values of patients with de novo and recurrent advanced cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development, and Information; the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Information Management Services; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

APPENDIX

Table A1.

Characteristics of Patients With Advanced Breast, Colorectal, or Lung Cancer, 2008 to 2011

Footnotes

Supported by National Cancer Institute grant R01CA172143 (M.J.H., D.P.R.) with additional support from the National Cancer Institute to the Cancer Research Network (U24C171524) and the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (R01CA105274 and U01CA195565). The study sponsors had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Michael J. Hassett, Mark C. Hornbrook, Debra P. Ritzwoller, Matthew Banegas

Financial support: Michael J. Hassett

Administrative support: Michael J. Hassett

Provision of study material or patients: Debra P. Ritzwoller

Collection and assembly of data: Michael J. Hassett, Shicheng Weng, Maureen O’Keeffe Rosetti, Nikki M. Carroll, Hajime Uno, Matthew Banegas, Mark C. Hornbrook

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Spending for Advanced Cancer Diagnoses: Comparing Recurrent Versus De Novo Stage IV Disease

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jop/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Matthew Banegas

Employment: Vir Biotechnology (I)

Research Funding: AstraZeneca (Inst)

Hajime Uno

Consulting or Advisory Role: Shionogi, Biogen, Roche

Mark C. Hornbrook

Research Funding: Medical Research Inc.

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hassett MJ, Uno H, Cronin AM, et al. Survival after recurrence of stage I-III breast, colorectal, or lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;49:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren JL, Yabroff KR, Meekins A, et al. Evaluation of trends in the cost of initial cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:888–897. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:630–641. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yabroff KR, Lund J, Kepka D, et al. Economic burden of cancer in the United States: Estimates, projections, and future research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:2006–2014. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12745. Chen CT, Li L, Brooks G, et al: Medicare spending for breast, prostate, lung, and colorectal cancer patients in the year of diagnosis and year of death. Health Serv Res, 53:2118-2132, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taplin SH, Barlow W, Urban N, et al. Stage, age, comorbidity, and direct costs of colon, prostate, and breast cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:417–426. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.6.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riley GF, Potosky AL, Lubitz JD, et al. Medicare payments from diagnosis to death for elderly cancer patients by stage at diagnosis. Med Care. 1995;33:828–841. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199508000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warren JL, Mariotto A, Melbert D, et al. Sensitivity of Medicare claims to identify cancer recurrence in elderly colorectal and breast cancer patients. Med Care. 2016;54:e47–e54. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warren JL, Yabroff KR. Challenges and opportunities in measuring cancer recurrence in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv134. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassett MJ, Uno H, Cronin AM, et al. Detecting lung and colorectal cancer recurrence using structured clinical/administrative data to enable outcomes research and population health management. Med Care. 2017;55:e88–e98. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engel-Nitz NM, Hao Y, Becker LK, et al. Costs and mortality of recurrent versus de novo hormone receptor-positive/HER2(-) metastatic breast cancer. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4:303–314. doi: 10.2217/cer.15.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karnon J, Kerr GR, Jack W, et al. Health care costs for the treatment of breast cancer recurrent events: Estimates from a UK-based patient-level analysis. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:479–485. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamerato L, Havstad S, Gandhi S, et al. Economic burden associated with breast cancer recurrence: Findings from a retrospective analysis of health system data. Cancer. 2006;106:1875–1882. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lidgren M, Wilking N, Jönsson B, et al. Resource use and costs associated with different states of breast cancer. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2007;23:223–231. doi: 10.1017/S0266462307070328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stokes ME, Thompson D, Montoya EL, et al. Ten-year survival and cost following breast cancer recurrence: Estimates from SEER-Medicare data. Value Health. 2008;11:213–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisen A, Fletcher GG, Gandhi S, et al. Optimal systemic therapy for early breast cancer in women: A clinical practice guideline. Curr Oncol. 2015;22:S67–S81. doi: 10.3747/co.22.2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khatcheressian JL, Wolff AC, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2006 update of the breast cancer follow-up and management guidelines in the adjuvant setting. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5091–5097. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn EE, Tang T, Lee JS, et al. Use of posttreatment imaging and biomarkers in survivors of early-stage breast cancer: Inappropriate surveillance or necessary care? Cancer. 2016;122:908–916. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steele SR, Chang GJ, Hendren S, et al. Practice guideline for the surveillance of patients after curative treatment of colon and rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:713–725. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Backhus LM, Farjah F, Zeliadt SB, et al: Predictors of imaging surveillance for surgically treated early-stage lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 98:1944-51, 2014; discussion 1951-1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Ritzwoller DP, Fishman PA, Banegas MP, et al. Medical care costs for recurrent versus de novo stage IV cancer by age at diagnosis. Health Serv Res. 2018;53:5106–5128. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, et al. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: Content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40:IV-3–IV-18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Edge SB: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (ed 7). New York, NY, Springer, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ritzwoller DP, Hassett MJ, Uno H, et al. Development, validation, and dissemination of a breast cancer recurrence detection and timing informatics algorithm. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:273–281. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, et al. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassett MJ, Ritzwoller DP, Taback N, et al. Validating billing/encounter codes as indicators of lung, colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer recurrence using 2 large contemporary cohorts. Med Care. 2014;52:e65–e73. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318277eb6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye X, Henk J. An Introduction to Recently Developed Methods for Analyzing Censored Cost Data, ISPOR Connections. Lawrenceville, NJ: ISPOR; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1616–1625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, et al. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bradley CJ, Yabroff KR, Mariotto AB, et al: Antineoplastic treatment of advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: Treatment, survival, and spending (2000 to 2011). J Clin Oncol 35:529-535, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Yabroff KR, Warren JL, Schrag D, et al. Comparison of approaches for estimating incidence costs of care for colorectal cancer patients. Med Care. 2009;47:S56–S63. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a4f482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banegas MP, Yabroff KR. Out of pocket, out of sight? An unmeasured component of the burden of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:252–253. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown ML, Riley GF, Schussler N, et al. Estimating health care costs related to cancer treatment from SEER-Medicare data. Med Care. 2002;40:IV-104–IV-117. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]