Abstract

PURPOSE

Pain, fatigue, and distress are common among patients with cancer but are often underassessed and undertreated. We examine the prevalence of pain, fatigue, and emotional distress among patients with cancer, as well as patient perceptions of the symptom care they received.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Seventeen Commission on Cancer–accredited cancer centers across the United States sampled patients with local/regional breast (82%) or colon (18%) cancer. We received 2,487 completed surveys (61% response rate).

RESULTS

Of patients, 76%, 78%, and 59% reported talking to a clinician about pain, fatigue, and distress, respectively, and 70%, 61%, and 54% reported receiving advice. Sixty-one percent of patients experienced pain, 74% fatigue, and 46% distress. Among those patients experiencing each symptom, 58% reported getting the help they wanted for pain, 40% for fatigue, and 45% for distress. Multilevel logistic regression models revealed that patients experiencing symptoms were significantly more likely to have talked about and received advice on coping with these symptoms. In addition, patients who were receiving or recently completed curative treatment reported more symptoms and better symptom care than did those who were further in time from curative treatment.

CONCLUSION

In our sample, 30% to 50% of patients with cancer in community cancer centers did not report discussing, getting advice, or receiving desired help for pain, fatigue, or emotional distress. This finding suggests that there is room for improvement in the management of these three common cancer-related symptoms. Higher proportions of talk and advice among those experiencing symptoms imply that many discussions may be patient initiated. Lower rates of talk and advice among those who are further in time from treatment suggest the need for more assessment among longer-term survivors, many of whom continue to experience these symptoms. These findings seem to be especially important given the high prevalence of these symptoms in our sample.

INTRODUCTION

Breast and colon cancer are two of the most common types of cancer in the United States.1 These cancers and their treatments—surgery, chemotherapy, biologic, and/or radiation therapy—often cause patients to experience significant physical and psychosocial symptoms and adverse effects.1-4 High levels of symptom burden among patients with cancer can result in significant limitations in daily activities, poor functioning, disability, and overall impairment in their health-related quality of life.5,6 Treatment-related symptoms are also a leading cause of patient nonadherence,7,8 which makes symptom control an important factor in the completion of guideline-recommended curative treatment. Despite the importance of controlling symptoms in cancer care, they are often underassessed, underreported, and undertreated.9-12

Three of the most common and debilitating symptoms among patients with cancer are pain, fatigue, and emotional distress.13,14 Deficits in the management of these symptoms may be attributed to barriers at the patient, clinician, and system levels.15-17 Examples of patient-level barriers include belief that the symptom cannot be improved and a reluctance to communicate with clinicians about it. Clinician- and system-level barriers include inadequate symptom screening, failure to reassess symptom status, and a lack of reimbursement for symptom management. These barriers can derail the effective management of symptoms.

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) play an important role in the measurement of symptom care processes and outcomes. Given the subjective nature of symptoms, a number of US and European guidelines recommend PRO measures as the preferred approach for symptom assessment in clinical trials and routine practice.10-12,18-20 PROs also are used to measure patient satisfaction with perceptions of care, including such process measures as clinician communication. For example, the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) patient surveys collect patient assessments of care quality in a variety of settings and are endorsed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.21-23 More recently, the National Quality Forum has published guidelines for the development of patient-reported performance measures.24 Patient perceptions of clinician–patient communication about specific symptoms can provide important insight into areas that must be improved to optimally manage symptoms among patients with cancer.

In this work, we examine the prevalence and predictors of cancer-related pain, fatigue, and distress, as well as patient perceptions of the symptom care they received. Our measures of patient perceptions of symptom care were derived from three important elements of symptom management recommended by guidelines: routine assessment of symptoms, provision of information and education about how to cope with symptoms, and patient satisfaction with care.10-12,18,19 Our data come from a large, population-based, multisite study of patients with breast and colon cancer around the time of curative treatment, conducted at 17 community cancer centers across the United States.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Setting and Design

Detailed methods for the Patient Reported Outcomes Symptoms and Side Effects Study (PROSSES) are provided elsewhere.25 PROSSES was approved by the National Cancer Institute institutional review board. PROSSES was conducted at 17 hospital-based community cancer centers participating in the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program, receiving 25,194 new cases of cancer in 2012 and reporting patients into the Rapid Quality Reporting System (RQRS) registry from the Commission on Cancer within 4 to 6 months of diagnosis.26,27 Patients were eligible for this study if they were diagnosed with stage I to III breast or colon cancer as their first primary cancer, eligible for an RQRS breast or colon Quality of Care Indicator,28 age 21 years or older, and not known to be deceased at the time of contact.

Eligible patients with breast and colon cancer (N = 4,175) were sampled between February 2011 and January 2013 using RQRS and were mailed a study packet with consent form, questionnaire, and instructions for those who chose to complete the survey online. Nonrespondents received up to two additional follow-up contacts. Of eligible patients, 2,487 completed the survey, most by mail and 9.4% online. Respondents were subsequently linked to their corresponding RQRS registry information on cancer diagnosis and treatment. Overall response rate was 61.1%. Differences between responders and nonresponders were negligible to small.25

Data

Patient-level data.

Most patient-level data came from questionnaires that underwent two rounds of cognitive testing with nine survivors of breast or colon cancer who came from a variety of racial and educational backgrounds. Type of cancer, stage, surgery, and health insurance data came from RQRS. Missing questionnaire data on such variables as age or months since chemotherapy were supplemented with data from RQRS. We created a variable with the four subgroups of patients considered in the analysis: females with colon cancer, males with colon cancer, females with breast cancer not receiving radiation treatment, and females with breast cancer receiving radiation treatment. Stratification by radiation treatment type among patients with breast cancer was based on an a priori hypothesis that symptom prevalence might differ on the basis of the receipt of this treatment modality.

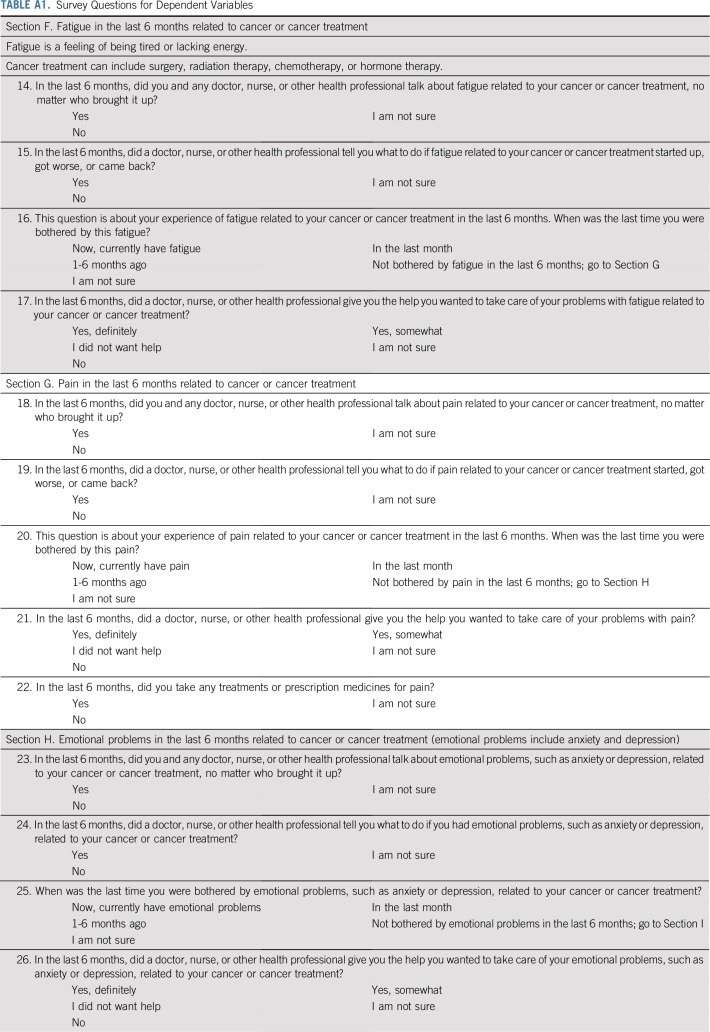

Our dependent variables were adapted from previously validated instruments used in federally funded studies29-32 and are similar to questions in the CAHPS Cancer Care Survey.33 For each of three symptoms—pain, fatigue, and distress (ie, emotional problems, including anxiety and depression) —we asked respondents four questions with a 6-month recall period:

Had the respondent talked with a clinician about a given symptom? The talk measures—that is, talk about pain.

Had a clinician explained what to do if the symptom started, became worse, or returned? The advice measures—that is, advice about pain.

Had they been bothered by the symptom because of their cancer? The cancer-related symptom prevalence measures.

Respondents who reported being bothered by a symptom within the past 6 months were asked whether a clinician had given them the help they wanted with that symptom. The help measures—that is, help for pain.

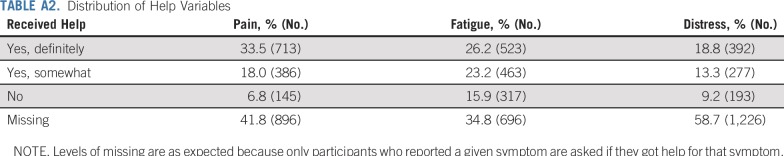

All 12 questions are provided in Appendix Table A1 (online only). The response options for the talk, advice, and prevalence questions were Yes or No. The response options for the help questions were Yes-definitely, Yes-somewhat, or No (distributions are listed in Appendix Table A2, online only). To facilitate comparisons between dependent variables, the help measures were dichotomized by combining the two least-frequent responses, Yes-somewhat and No, into one category.

Cancer center–level variables.

Cancer center–level data—hospital bed count and urban/rural indicator—were obtained from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Provider of Services file.

Statistical Analysis

Respondents were excluded from analyses for the following reasons: survey completed by someone other than intended (n = 16); reported not seeing a clinician about their cancer during the past 6 months (n = 72); participant responded to less than 30% of the key symptom management quality-of-care indicators (n = 120); from a facility with too few respondents (n = 8) to include in multilevel analysis; male with breast cancer (n = 5); or patient with colon cancer reporting radiation treatment (n = 9). The final analytic sample consisted of 2,257 registry-linked respondents from 16 community cancer centers.

As a result of the nested nature of PROSSES—that is, patients within cancer centers—multilevel logistic regression models were used to explore individual and hospital-level predictors of the 12 outcomes. Initial variables considered for inclusion in multivariable models were based on previous literature. Variables that were not significantly associated (α = .05) with any of the 12 outcomes in bivariable analyses were dropped from multivariable models.

RESULTS

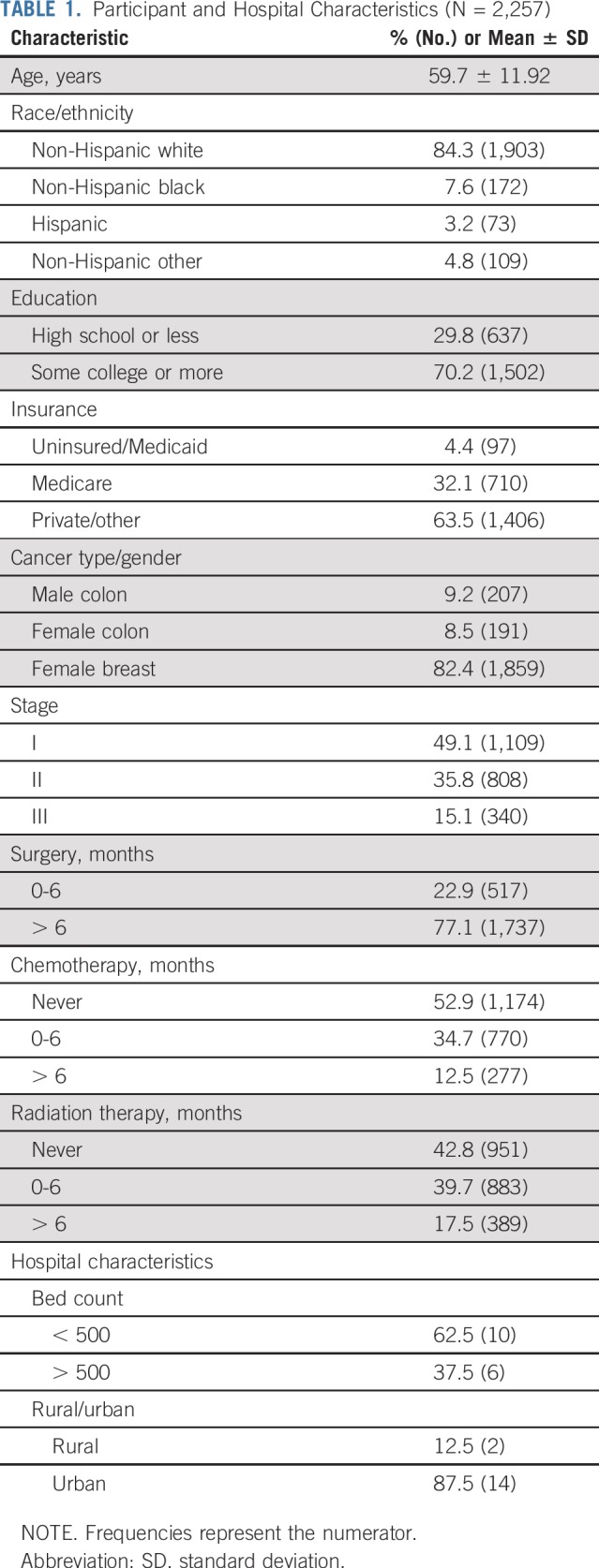

Participant medicodemographic characteristics are listed in Table 1. Study respondents were primarily females with breast cancer (82.4%) and identifying as non-Hispanic white (84.3%). Of participants, 49.1% were diagnosed with stage I cancer, 35.8% stage II cancer, and 15.1% stage III cancer. Of patients, 22.9% completed the questionnaire within 6 months of surgery, 34.7% within 6 months of chemotherapy, and 39.7% within 6 months of radiation.

TABLE 1.

Participant and Hospital Characteristics (N = 2,257)

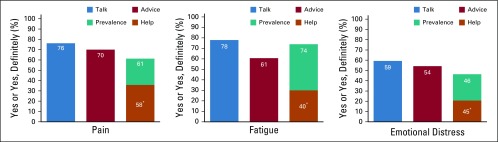

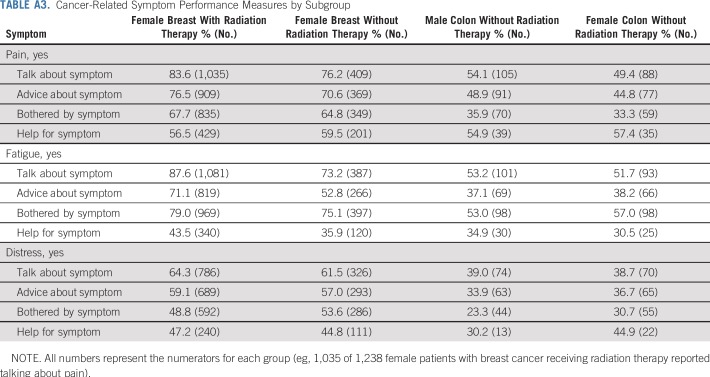

Figure 1 summarizes responses to the 12 symptom management outcomes across patients in this study. Among all patients, 76.2% of patients reported having talked with their clinician about pain, 78.0% about fatigue, and 59.2% about distress. A lower proportion reported getting advice from clinicians on coping with these symptoms (pain, 70.0%; fatigue, 60.6%; distress, 54.3%). The prevalence of cancer-related symptoms was 61.2% for pain, 73.9% for fatigue, and 46.4% for distress. Only those who reported a given symptom were asked if they got help for it. Among patients who reported pain, 57.5% indicated clinicians gave the desired amount of help for it. Among those who reported fatigue, 40.1% indicated getting wanted help. Among those who reported emotional distress, 45.5% indicated getting wanted help. Outcome prevalence is reported by subgroup in Appendix Table A3 (online only).

FIG 1.

Patient perceptions of cancer-related symptom management. Denominators for percentages: Pain: talk, 2,180; advice, 2,103; prevalence. 2,179; help, 1,250. Fatigue: talk, 2,166; advice, 2,045; prevalence, 2,145; help, 1,303. Emotional distress: talk, 2,156; advice, 2,072; prevalence, 2,148; help, 862. The orange bar indicates the fraction of patients who experienced the symptom who indicated they definitely got the help they wanted. (*) Only asked among those experiencing the symptom.

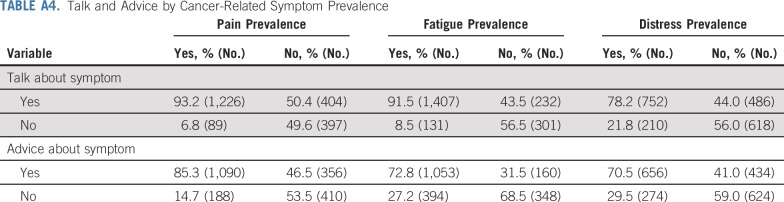

Cancer center bed count was not significantly associated with any of the 12 outcomes in bivariable models and was therefore excluded from multivariable models. All other considered variables were included in the 12 multivariable multilevel models: participant age, race/ethnicity, education, insurance status, cancer type/gender/radiation treatment, stage, surgery, and chemotherapy status. Symptom prevalence was only relevant to the six talk and advice measures and included in those models. Patients who experienced a symptom were more likely to report talking and having received advice about that symptom from clinicians (Appendix Table A4, online only). However, not everyone who had a symptom talked with or got advice from a clinician about it—6.8% of patients who reported pain did not talk about it and 29.5% of patients who experienced distress did not get advice.

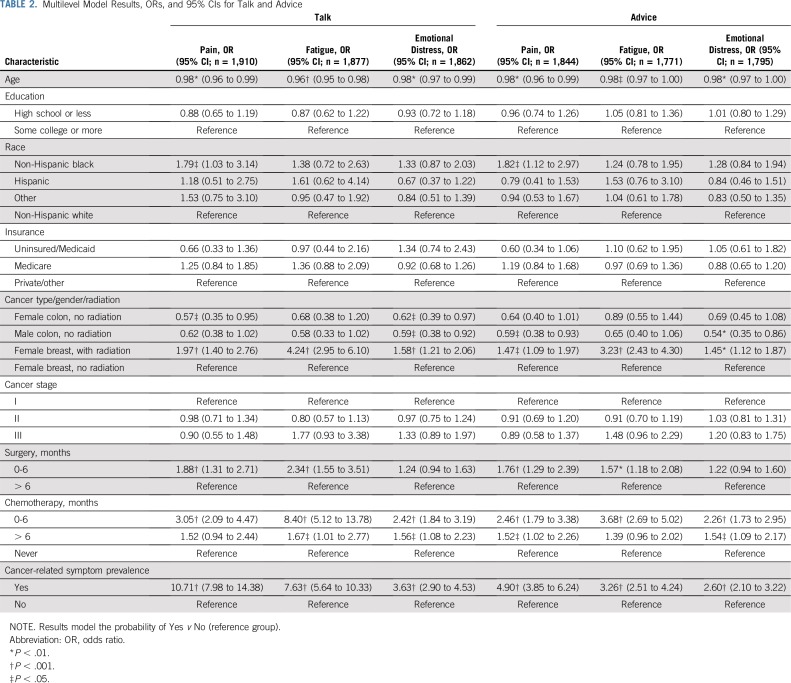

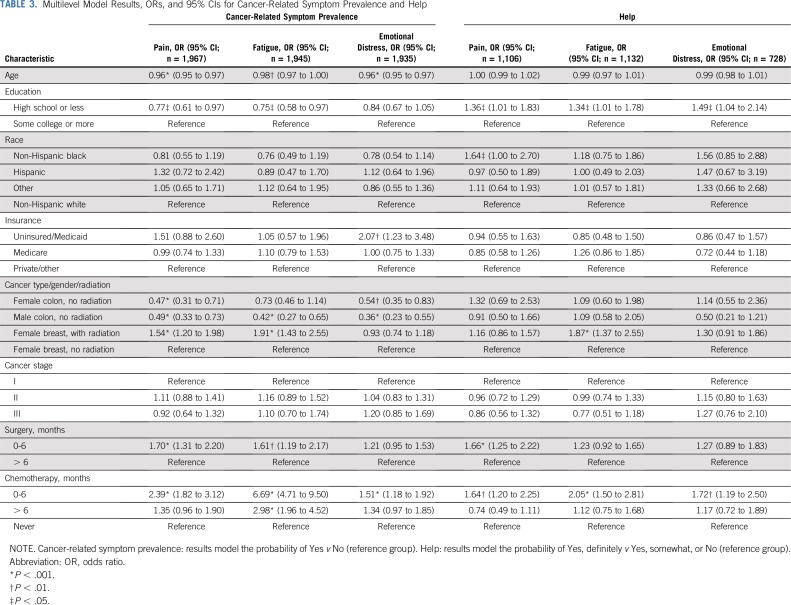

Results from multilevel multivariable logistic regressions predicting patient reports of talk and advice about symptoms are shown in Table 2, whereas models for symptom experience and help measures are listed in Table 3. Experiencing a symptom was strongly associated with having talked about and received advice about that symptom: pain (talk: odds ratio [OR], 10.71; advice: OR, 4.90), fatigue (talk: OR, 7.63; advice: OR, 3.26), and distress (talk: OR, 3.63; advice: OR, 2.60). Older age was associated with a significant decrease in the odds of having talked about pain (OR, 0.98), fatigue (OR, 0.96), and distress (OR, 0.98). Associations with age were similar for advice and symptom prevalence measures for each of the three symptoms. Non-Hispanic blacks were more likely to report talking about, getting advice about, or getting help for pain than non-Hispanic whites, although these results were only weakly statistically significant.

TABLE 2.

Multilevel Model Results, ORs, and 95% CIs for Talk and Advice

TABLE 3.

Multilevel Model Results, ORs, and 95% CIs for Cancer-Related Symptom Prevalence and Help

Female patients with breast cancer who received radiation therapy were more likely to have talked about pain (OR, 1.97), fatigue (OR, 4.24), and distress (OR, 1.58) than those who did not receive radiation therapy. Among patients with breast cancer, radiation therapy was also associated with greater odds of getting advice about all three symptoms, experiencing pain and fatigue, and getting help for fatigue. Patients with breast or colon cancer who underwent surgery within 6 months of questionnaire completion were more likely to have talked, received advice, and experienced pain and fatigue, as well as being more likely to have received help for pain. Patients who received chemotherapy within 6 months of questionnaire completion were more likely to have talked about pain (OR, 3.05), fatigue (OR, 8.40), and distress (OR, 2.42) than those who never received chemotherapy. More recent chemotherapy was also associated with an increased likelihood of receiving advice, experiencing symptoms, and receiving help for all symptoms. In our sample, talk and advice about symptoms are more common around the time of curative treatment than later, even when controlling for symptom prevalence. Symptoms are more common around curative treatment than later, and among those who experience a symptom, help is more likely around curative treatment than later.

Comparisons between patients with colon and breast cancer are possible among patients who did not receive radiation treatment. Compared with women with breast cancer, both women and men with colon cancer were less likely to report talking about distress and experiencing pain or distress. Male patients with colon cancer were less likely to report getting advice about pain or distress and experiencing fatigue than patients with breast cancer. Female patients with colon cancer were less likely to report talking about pain. Tests for gender differences among colon cancer patients were nonsignificant, with the exception of one outcome (fatigue prevalence, results not shown), which suggests that differences between patients with colon and breast cancer in our sample are not on the basis of gender.

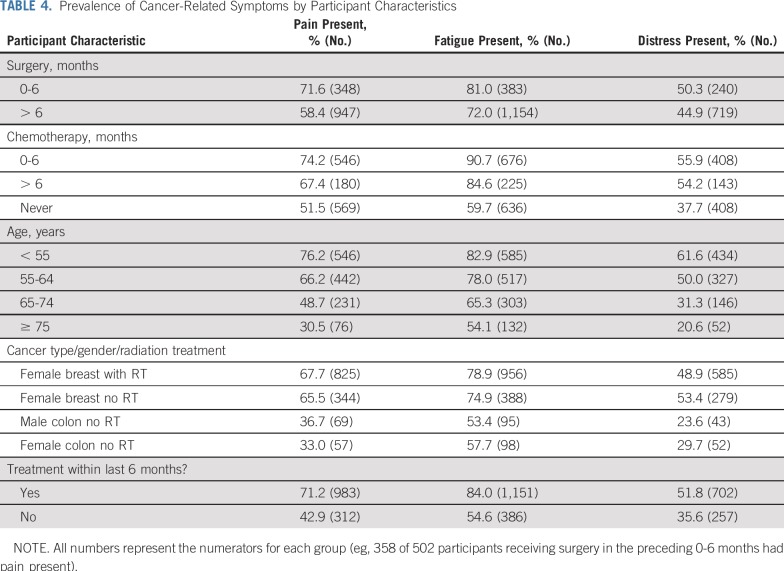

Whereas symptoms are more prevalent within 6 months of receiving treatment, many patients continue to experience symptoms further from treatment (Table 4). Patients who received no treatment—surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation—within the last 6 months continued to be bothered by pain (42.9%), fatigue (54.6%), and distress (35.6%).

TABLE 4.

Prevalence of Cancer-Related Symptoms by Participant Characteristics

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that there is room for improvement in the management of pain, fatigue, and emotional distress among patients with cancer in the community oncology setting. In our sample, 30% to 50% of patients did not report discussing, getting advice, or receiving desired help for these three common symptoms. Of the three symptoms, patients were most likely to get advice (70%) and wanted help (58%) for pain. This is consistent with the prominence of well-established treatment protocols for pain. Fatigue was the most common symptom (74%) and many patients reported talking about it (78%), whereas those who reported fatigue were least likely to report getting wanted help for it (40%), possibly reflecting the challenges in treating this common but complicated symptom. Patients reported getting advice about emotional distress approximately half the time (54%), possibly reflecting clinicians’ lack of familiarity and resources for dealing with distress and patients’ reticence to mention mental health issues as a result of social stigma. This work expands on similar findings reported among Veterans Affairs patients with colorectal cancer29 by adding breast cancer and a more generalizable, community-based sample. These findings seem to be important given the high prevalence of these symptoms in our sample (pain, 61%; fatigue, 74%; distress, 46%) and reported elsewhere.20,34,35

Our multilevel models demonstrate that patients who reported a given symptom were much more likely to report talking about or getting advice about the symptom. This suggests that patients who experienced these symptoms may be initiating these interactions. Given the limited time during visits, clinicians may focus on symptoms brought up by patients. Unfortunately, patients with cancer may be reluctant to initiate discussions about symptoms during clinical visits even when bothered by them.36,37 Our data show that 6.8% to 29.5% of patients with a given symptom do not report talking about or getting advice about it from a clinician. According to symptom care guidelines, clinicians should assess all patients with cancer for these symptoms.10-12,19 Lack of universal, or near-universal, assessment is a missed opportunity.

Similarly, we find that patients who are further in time from treatment are less likely to report discussing or getting advice about symptoms, even though a sizeable proportion of these patients continue to experience these symptoms. For example, 68% of patients more than 6 months from receiving chemotherapy continued to be bothered by pain, 85% by fatigue, and 54% by distress. Likewise, older patients or those with colon cancer are less likely to report being bothered by cancer-related symptoms, but symptom prevalence remains high for these groups (Table 4). These findings suggest oncology and primary care health systems should more proactively assess and discuss symptoms, even among patients who are less likely to experience them.

A national US survey found prevalence rates for all-causes pain to be similar for the age groups 45 to 64 years and 65 to 84 years, but lower for those younger than age 45 years.38 The vast majority of our sample are age 45 to 84 years. The lower pain prevalence among older patients in our sample may reflect our use of cancer-specific pain and the tendency of working-age survivors to report more cancer-related problems than retirement-age survivors.39

Elsewhere, we report that cancer centers demonstrated significant variation on these symptom management measures, which suggests that lower-scoring centers have room to improve their performance.40 Improvements might be realized by educating patients to increase their assertiveness in seeking care for symptoms and adherence to treatment regimens.41 Increasing clinician knowledge about and adherence to symptom treatment guidelines10-12 through training should also improve symptom outcomes. Providing clinicians with timely, valid, and easy-to-use information on symptoms has been demonstrate to improve symptom management.42-44 With proper implementation, clinical use of PROs can improve symptom care and other outcomes.45,46

This work highlights patient perceptions of symptom management, which are different from measures of symptom intensity. Given the highly toxic nature of many cancer treatments, some symptoms may be inevitable; therefore, process measures of symptom care, like those used in this study, are an important part of assessing overall quality of care.10-12 Process measures of symptom care can also be abstracted from medical records,47 which has the advantage of capturing clinical symptom assessments that the patient forgot. Limitations of this approach include the cost of medical record abstraction and clinicians’ tendency to underreport symptoms relative to patient report.48 Patient-reported measures—for example, the CAHPS Cancer Care Survey—can capture instances in which symptom assessment is suboptimal and reflect the patient’s experience, making them especially important for achieving patient-centered care.

As with most survey research, results of this study may be subject to bias as a result of missing data, recall bias, or other issues. Nonresponse bias may be present, but the good response rate and similarity between respondents and nonrespondents with regard to medicodemographic characteristics suggests that this is relatively low.25 Our symptom prevalence questions assessed whether respondents were bothered by symptoms or not, so we were unable to differentiate between mild and severe symptoms. This survey was fielded before the Commission on Cancer implemented its standard for psychosocial distress screening in 2015 at accredited cancer programs,49 so symptom care may have improved since then, especially for distress. Our ability to investigate center-level predictors was limited by a lack of variables on center-level availability of palliative care, supportive care or nurses, marginal statistical power for multilevel analyses,50 and homogeneity of participating centers—all centers participated in the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program. Whereas the sample was similar to the populations of the participating centers, it could have been more diverse with regard to cancer type and ethnicity. Non-Hispanic black was the only minority group with sufficient numbers in our sample to support comparison with whites. Non-Hispanic black race/ethnicity was weakly associated with three outcomes in a direction that suggested better pain care. Some previous studies have found racial disparities in symptomology.51,52 Our result may be a result of chance, exclusion of participants with advanced stage, or all race groups being treated at the same group of facilities. Disparities in other studies may be driven by minorities being more likely to attend facilities that provide lower-quality care.53

Appropriate use of PROs that measure cancer symptoms and patients’ perceptions of their care can improve our understanding through research, performance measurement, and clinical assessment. These data may inform policy and clinical standards to improve the care of patients with cancer and ultimately improve their quality of life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program centers and patients for participating in this study. The authors also thank Kenneth Portier and James Hodge for statistical consultation on this paper.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Survey Questions for Dependent Variables

TABLE A2.

Distribution of Help Variables

TABLE A3.

Cancer-Related Symptom Performance Measures by Subgroup

TABLE A4.

Talk and Advice by Cancer-Related Symptom Prevalence

Footnotes

Funded by the American Cancer Society Intramural Research Department and federal funds from the National Cancer Institute under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E.

Presented at the 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology Quality Care Symposium, Boston, MA, October 17-18, 2014.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the American Cancer Society or the US Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

This work does not necessarily reflect the views policy or position of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST AND DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Disclosures provided by the authors and data availability statement (if applicable) are available with this article at DOI https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.01579.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Tenbroeck G. Smith, Kathleen M. Castro, Neeraj K. Arora, Kevin Stein, Otis W. Brawley, Ryan M. McCabe, Steven B. Clauser, Elizabeth Ward

Financial support: Tenbroeck G. Smith, Steven B. Clauser

Administrative support: Otis W. Brawley, Elizabeth Ward

Collection and assembly of data: Tenbroeck G. Smith, Alyssa N. Troeschel, Kevin Stein

Data analysis and interpretation: Tenbroeck G. Smith, Alyssa N. Troeschel, Kathleen M. Castro, Neeraj K. Arora, Kevin Stein, Joseph Lipscomb, Ryan M. McCabe, Steven B. Clauser

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Perceptions of Patients With Breast and Colon Cancer of the Management of Cancer-Related Pain, Fatigue, and Emotional Distress in Community Oncology

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Tenbroeck G. Smith

Employment: Geovax (I)

Kevin Stein

Research Funding: Charleston Labs (Inst), Takeda (Inst), Eli Lilly (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Celgene (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), EMD Serono (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Jazz Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Janssen Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Pharmacyclics (Inst), Novartis (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society Cancer treatment and survivorship: Facts and figures 2016-2017. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/survivor-facts-figures.html

- 2.Walling AM, Weeks JC, Kahn KL, et al. Symptom prevalence in lung and colorectal cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohsumi S, Shimozuma K, Kuroi K, et al. Quality of life of breast cancer patients and types of surgery for breast cancer: Current status and unresolved issues. Breast Cancer. 2007;14:66–73. doi: 10.2325/jbcs.14.66. Erratum: Breast Cancer 14:254, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourdon M, Blanchin M, Tessier P, et al. Changes in quality of life after a diagnosis of cancer: A 2-year study comparing breast cancer and melanoma patients. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:1969–1979. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1244-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.So WKW, Marsh G, Ling WM, et al. The symptom cluster of fatigue, pain, anxiety, and depression and the effect on the quality of life of women receiving treatment for breast cancer: A multicenter study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36:E205–E214. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.E205-E214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kroenke K, Zhong X, Theobald D, et al. Somatic symptoms in patients with cancer experiencing pain or depression: Prevalence, disability, and health care use. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1686–1694. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banna GL, Collovà E, Gebbia V, et al. Anticancer oral therapy: Emerging related issues. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cella D, Fallowfield LJ. Recognition and management of treatment-related side effects for breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107:167–180. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9548-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levit LA, Balogh EP, Nass SJ, et al.(eds)Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Adult cancer pain, version 1.2018. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pain.pdf

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Cancer-related fatigue, version 2.2018. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0078. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/fatigue.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Distress management, version 2.2018. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/distress.pdf

- 13.Barbera L, Seow H, Howell D, et al. Symptom burden and performance status in a population-based cohort of ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2010;116:5767–5776. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institutes of Health Symptom management in cancer: Pain, depression and fatigue—State-of-the-Science Conference Statement. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2003;17:77–97. doi: 10.1080/j354v17n01_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsen R, Liubarskiene Z, Møldrup C, et al. Barriers to cancer pain management: A review of empirical research. Medicina (Kaunas) 2009;45:427–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Donaghy K, et al. Patient-related barriers to fatigue communication: Initial validation of the fatigue management barriers questionnaire. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:481–493. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00518-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeom HE, Heidrich SM. Effect of perceived barriers to symptom management on quality of life in older breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32:309–316. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819e239e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bower JE, Bak K, Berger A, et al. Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: An American Society of Clinical oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1840–1850. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersen BL, DeRubeis RJ, Berman BS, et al. Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1605–1619. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell SA, Hoffman AJ, Clark JC, et al. Putting evidence into practice: An update of evidence-based interventions for cancer-related fatigue during and following treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(suppl):38–58. doi: 10.1188/14.CJON.S3.38-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Malley AJ, Zaslavsky AM, Elliott MN, et al. Case-mix adjustment of the CAHPS Hospital Survey. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:2162–2181. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00470.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson ML, Rodriguez HP, Solorio MR. Case-mix adjustment and the comparison of community health center performance on patient experience measures. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:670–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality CAHPS: Assessing health care quality from the patient’s perspective. https://cahps.ahrq.gov/about-cahps/cahps-program/cahps_brief.html

- 24.National Quality Forum Patient-reported outcomes in performance measurement. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2012/12/Patient-Reported_Outcomes_in_Performance_Measurement.aspx

- 25.Smith TG, Castro KM, Troeschel AN, et al. The rationale for patient-reported outcomes surveillance in cancer and a reproducible method for achieving it. Cancer. 2016;122:344–351. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program About—NCCCP overview. http://ncccp.cancer.gov/about/index.htm

- 27.Stewart AK, McNamara E, Gay EG, et al. The Rapid Quality Reporting System: A new quality of care tool for CoC-accredited cancer programs. J Registry Manag. 2011;38:61–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halpern MT, Spain P, Holden DJ, et al. Improving quality of cancer care at community hospitals: Impact of the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program pilot. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:e298–e304. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.000937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Ryn M, Phelan SM, Arora NK, et al. Patient-reported quality of supportive care among patients with colorectal cancer in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:809–815. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.4302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Arora NK, et al. Patients’ experiences with care for lung cancer and colorectal cancer: Findings from the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4154–4161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arora NK, Reeve BB, Hays RD, et al. Assessment of quality of cancer-related follow-up care from the cancer survivor’s perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1280–1289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malin JL, Ko C, Ayanian JZ, et al. Understanding cancer patients’ experience and outcomes: Development and pilot study of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance patient survey. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:837–848. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality CAHPS Cancer Care Survey. doi: 10.1080/15360280802537332. https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/cancer/index.html [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, Hochstenbach LMJ, Joosten EAJ, et al. Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:107.e90–1090.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weis J. Cancer-related fatigue: Prevalence, assessment and treatment strategies. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11:441–446. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arora NK, Jensen RE, Sulayman N, et al. Patient-physician communication about health-related quality-of-life problems: Are non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors willing to talk? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3964–3970. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.6705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Detmar SB, Aaronson NK, Wever LD, et al. How are you feeling? Who wants to know? Patients’ and oncologists’ preferences for discussing health-related quality-of-life issues. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3295–3301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.18.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults: United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1001–1006. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker F, Denniston M, Smith T, et al. Adult cancer survivors: How are they faring? Cancer. 2005;104(suppl):2565–2576. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Troeschel A, Smith T, Castro K, et al. The development and acceptability of symptom management quality improvement reports based on patient-reported data: An overview of methods used in PROSSES. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:2833–2843. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1305-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett MI, Bagnall A-M, José Closs S. How effective are patient-based educational interventions in the management of cancer pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2009;143:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Baez L, et al. Pain and treatment of pain in minority patients with cancer. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Minority Outpatient Pain Study. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:813–816. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoekstra J, de Vos R, van Duijn NP, et al. Using the symptom monitor in a randomized controlled trial: The effect on symptom prevalence and severity. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Temel JS, Pirl WF, Lynch TJ. Comprehensive symptom management in patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2006;7:241–249. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2006.n.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:557–565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:197–198. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.American Society of Clinical Oncology Summary of current QOPI measures. http://www.asco.org/institute-quality/summary-current-qopi-measures

- 48.Basch E, Jia X, Heller G, et al. Adverse symptom event reporting by patients vs clinicians: Relationships with clinical outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1624–1632. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.American College of Surgeons Cancer program standards 2012: Ensuring patient-centered care. V1.2.1. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.ashx

- 50.Moineddin R, Matheson FI, Glazier RH. A simulation study of sample size for multilevel logistic regression models. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: Causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain. 2009;10:1187–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoon J, Malin JL, Tisnado DM, et al. Symptom management after breast cancer treatment: Is it influenced by patient characteristics? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108:69–77. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR.(eds)Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2003http://www.nap.edu/read/12875/chapter/1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]