Abstract

Context

Sport specialization has been defined as year-round intensive training in a single sport to the exclusion of other sports. A commonly used survey tool created by Jayanthi et al, which classifies athletes as having a low, moderate, or high level of specialization, categorizes only athletes answering yes to “Have you quit other sports to focus on a main sport?” as highly specialized. We hypothesized that a measureable number of year-round, single-sport athletes have never played other sports and, therefore, may be inaccurately classified as moderately specialized when using this tool, even though most experts would agree they should be viewed as highly specialized.

Objective

To determine the proportion of athletes misclassified as moderately rather than highly specialized because they never played a previous sport.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Hospital-based pediatric outpatient sports medicine clinic.

Patients or Other Participants

Injured athletes aged 12 to 17 years who presented to the clinic between 2015 and 2017 and completed a sports-participation survey (n = 917).

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Sport-specialization level.

Results

Of 917 participants, 299 (32.6%) played a single sport more than 8 months per year, and 208/299 (69.6%) had previously quit other sports (highly specialized), whereas 91 (30.4%) had never played other sports (highly specialized and misclassified as moderate). Individual-sport athletes had a 2.03 times greater risk of being highly specialized and misclassified as moderate than team-sport athletes (relative risk = 2.03 [95% confidence interval = 1.37, 3.00]). Females had a 1.70 times greater risk of being misclassified as moderately specialized than males (relative risk 1.70 [95% confidence interval = 1.07, 2.70]). Of the 3 sports with the largest number of athletes, artistic gymnastics had the highest proportion (51.2%) who had never played other sports.

Conclusions

The commonly used specialization survey misclassified a substantial number of highly specialized athletes as moderately specialized. Researchers should consider adding a fourth survey question, “Have you only ever played 1 sport?” to identify and better study this unique subset of misclassified athletes.

Keywords: youths, adolescents, children, organized sports

Key Points

The commonly used sport-specialization scale misclassified approximately 30% of highly specialized athletes as moderately specialized.

Individual-sport athletes and females had a greater risk of being highly specialized and misclassified as moderately specialized compared with team-sport athletes and males.

Further study of this subset of highly specialized athletes who have no prior sporting experiences is important to determine whether their risk for injury differs from that of athletes who were previously exposed to other sports.

Approximately 60 million youth athletes in the United States between the ages of 6 and 18 participate in organized athletics.1 Accompanying the increase in youth sports participation has been the movement toward sport specialization at an early age. The most commonly used definition of specialization is “year-round intensive training in a single sport at the exclusion of other sports.”2(p1472) Based on this definition, a 3-question survey tool has been constructed by Jayanthi et al3 and used in several previous studies2,4,5 to classify an athlete's degree of sport specialization as low, moderate, or high. These questions are (1) “Can you pick a main sport?” (2) “Do you train more than 8 months per year for a main sport?” and (3) “Did you quit other sports to focus on a main sport?” An athlete must meet all 3 criteria to be considered highly specialized. Answering yes to 2 of the 3 questions classifies an athlete as moderately specialized. Those who answer yes to 1 or 0 questions are considered to have a low level of specialization. The prevalence of high specialization in youth athlete populations is estimated to be between 13.4% and 37.5%.2,6,7 Bell et al2 reported that 36.4% of the high school–aged athletes in their study were highly specialized. In several studies,2,3,7,8 researchers showed that highly specialized athletes were at greater risk for overuse injury compared with low-specialization athletes.

We hypothesized that the number of single-sport athletes who trained more than 8 months per year for their sport but had never played any other sports was substantial. Thus, they could not satisfy the third criterion and, therefore, were classified as being moderately specialized. We believe most experts in this area would agree that these athletes should be considered highly specialized. Single-sport athletes who have never played any other sports are likely at similar or even greater risk for overuse injury compared with highly specialized athletes and, in fact, may be at even higher risk for injury because they were not exposed to previous sports and thus did not benefit from the diversification of movement patterns other sports provide.3,9 The purpose of our study was to determine the proportion of athletes that the 3-question specialization survey misclassified as moderately rather than highly specialized because they never played a previous sport.

METHODS

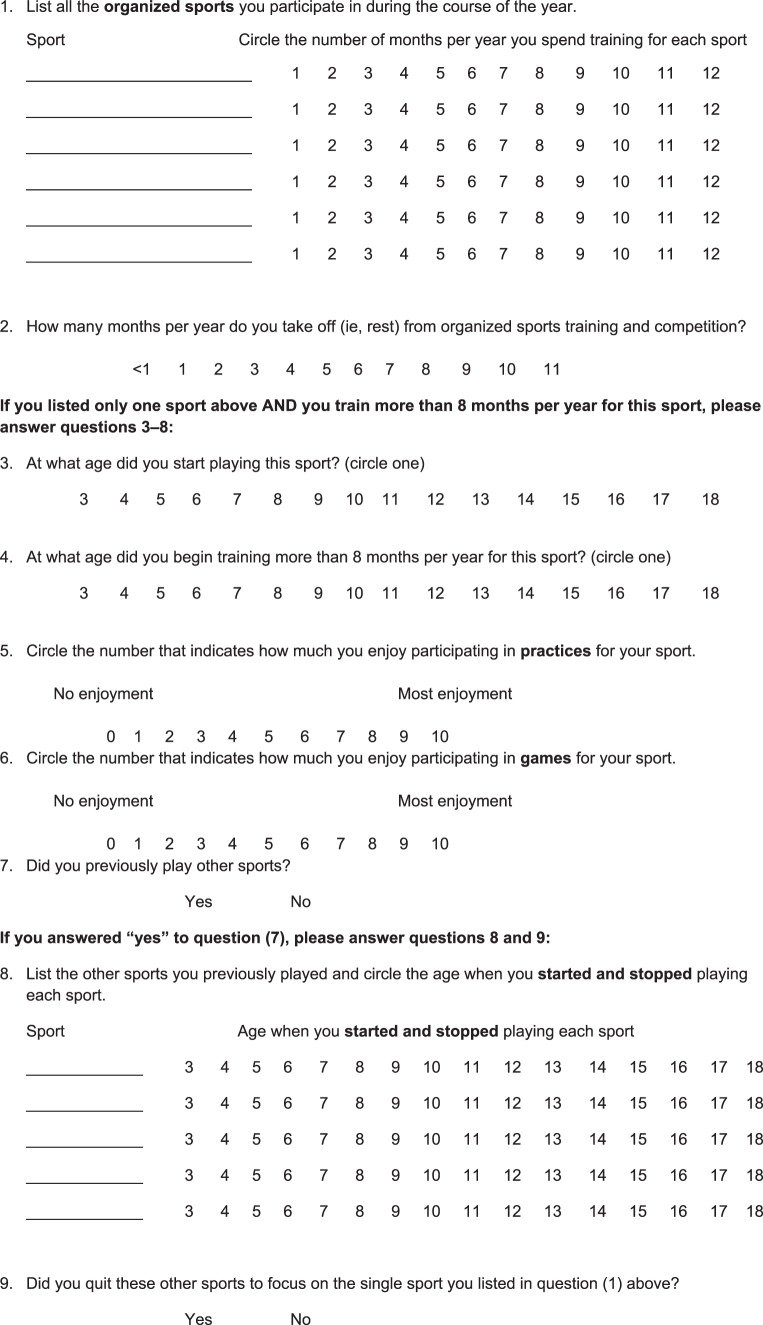

The Institutional Review Board at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital approved this study. We retrospectively reviewed the charts of patients who presented to the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's sports medicine clinic between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2017. Patients aged 12 to 17 years who completed a sports-participation survey (Appendix) as part of their clinical visit were included in this study. Patients were excluded if they did not play any organized sports. The survey included questions that allowed us to classify athletes as having a low, moderate, or high level of sport specialization according to the same 3-point system used by Jayanthi et al,3 whereby 1 point each was assigned for (1) playing only 1 sport, (2) training for that 1 sport more than 8 months per year, and (3) quitting all other sports to focus on the main sport. However, our survey contained an additional question asking if the athlete had previously played any other sports. This allowed us to create a fourth category for those who were single-sport athletes training more than 8 months per year but who answered no to the question about quitting other sports because they had never played any other sports. For the purposes of this study, we labeled this fourth group as highly specialized misclassified as moderately specialized.

The single-sport athletes' main sports were classified as either team or individual sports according to the same criteria used by previous investigators10,11 who defined a team sport as “a sport in which athletes play with others at the time of play.” The 10 athletes who indicated their sport as other were excluded from the team- and individual-sport comparisons.

Statistical analysis was performed using R software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of highly specialized athletes who previously played other sports versus those who had never played a previous sport (high specialization misclassified as moderate). A χ2 test and relative risk ratio were used to compare single-sport athletes who trained more than 8 months per year and quit other sports to focus on their main sport with single-sport athletes who trained more than 8 months per year but had never played other sports by individual or team sport and by sex. P values were 2 tailed, and .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

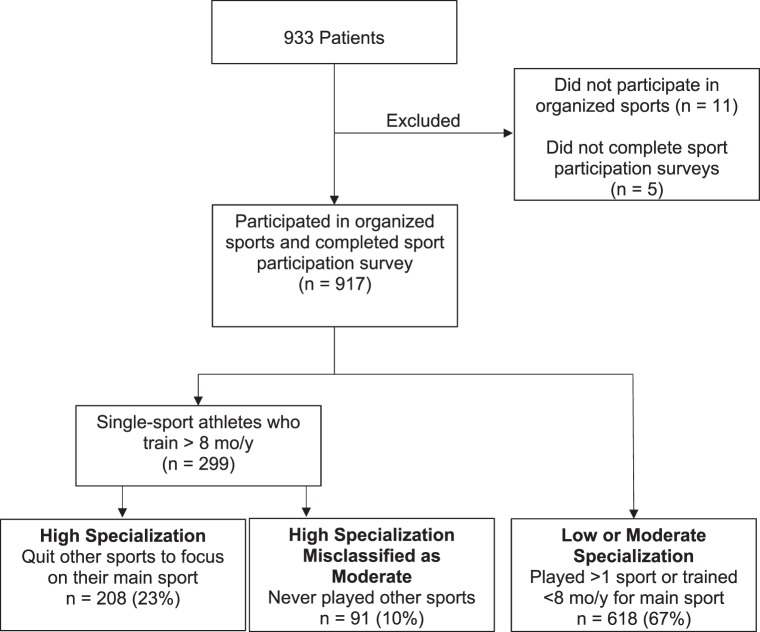

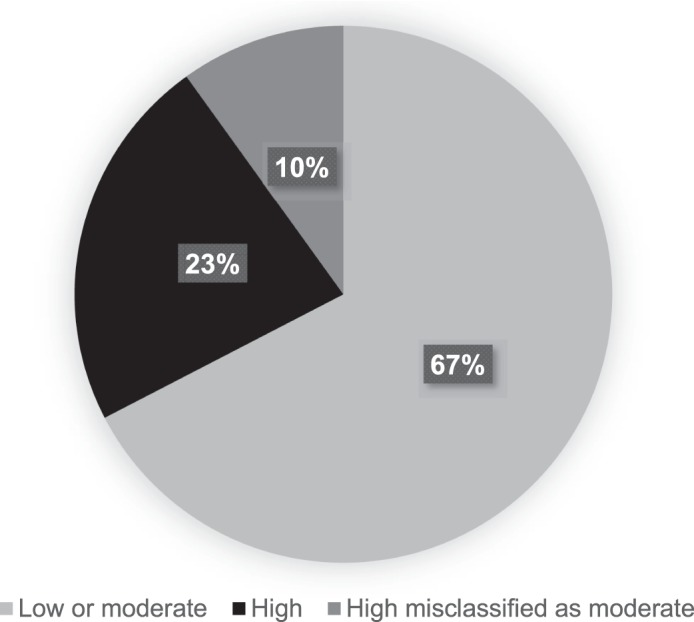

Of the 933 patients initially identified by chart review, 917 (98.3%) played at least 1 organized sport and had completed a sports-participation survey (Figure 1). Of the 917 athletes, 618 (67.4%) met the criteria for either low or moderate specialization based on earning only 0 to 2 points on the 3-point scale, either because they reported playing multiple sports (ie, could not pick a main sport) or trained 8 months or fewer per year for their main sport or both. The remaining 299 (32.6%) athletes reported playing only 1 sport and training more than 8 months per year for that sport, thereby earning at least 2 points on the specialization scale, meeting the criteria for at least moderate specialization. Of these 299 athletes, 208 (69.6%) had previously quit other sports to focus on their main sport and therefore earned 3 points and met the criteria for high specialization, whereas 91 (30.4%) had never played a previous sport and thus failed to earn a third point (high specialization misclassified as moderate; Figure 2). Age was similar for all groups (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Classification of patients into sport-specialization categories.

Figure 2.

Proportion of athletes in each sport-specialization category.

Table 1.

Athlete Characteristics Across Levels of Sport Specialization

| Sport-Specialization Category |

Athletes, n |

Age, y (Mean ± SD) |

Female Sex, % |

Individual-Sport Athletes, n |

Team-Sport Athletes, n |

| Total | 917 | 15.1 ± 1.6 | 61.5 | b | b |

| Low or moderatea | 618 | 15.0 ± 1.6 | 56.5 | b | b |

| Single-sport athletes training >8 mo/y | 299 | 15.3 ± 1.5 | 71.9 | 151 | 138 |

| High | 208 | 15.4 ± 1.5 | 67.8 | 91 | 111 |

| High misclassified as moderate | 91 | 15.0 ± 1.6 | 81.3 | 60 | 27 |

Low or moderate specialization: athletes who played ≥1 sport or a single sport but trained >8 months/year for that sport.

Totals could not be calculated because most athletes at a low or moderate level of specialization played >1 sport and so could not be classified as individual- or team-sport athletes.

Among the highly specialized and the highly specialized misclassified as moderate athletes, the 3 most frequently reported main sports were soccer (n = 51), dance (n = 43), and artistic gymnastics (n = 41; Table 2). The proportions of highly specialized misclassified as moderate athletes who reported one of these as their main sport were 51.2% (n = 21/41) for artistic gymnastics, 46.5% (n = 20/43) for dance, and 33.3% (n = 17/51) for soccer. Females had a 1.7 times greater risk of being categorized as high specialization misclassified as moderate than males (relative risk [RR] = 1.70; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.07, 2.70). The risk of being highly specialized misclassified as moderate was also greater for individual- versus team-sport athletes (RR = 2.03; 95% CI = 1.37, 3.00). Being an individual-sport athlete and being a female gymnast or dancer were highly correlated, with a correlation coefficient of 0.622 (P < .001).

Table 2.

Main Sports for Single-Sport Athletes Who Trained >8 Months/Year By High Specialization and High Specialization Misclassified as Moderate Groups

| Sport Type |

Sport |

Patients, No. |

No. (%) |

|

| High Specialization |

High Specialization Misclassified as Moderate |

|||

| Team | Soccer | 51 | 34 (66.7) | 17 (33.3) |

| Volleyball | 20 | 17 (85.0) | 3 (15.0) | |

| Basketball | 19 | 17 (89.5) | 2 (20.5) | |

| Cheerleading | 12 | 10 (83.3) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Ice hockey | 10 | 10 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Softball | 10 | 9 (90.0) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Baseball | 7 | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Football | 5 | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Lacrosse | 3 | 3 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Field hockey | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Individual | Dance | 43 | 23 (53.5) | 20 (46.5) |

| Artistic gymnastics | 41 | 20 (48.8) | 21 (51.2) | |

| Figure skating | 12 | 9 (75.0) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Cross-country, track, running | 11 | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.10) | |

| Swimming | 11 | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.10) | |

| Tennis | 10 | 7 (70.0) | 3 (30.0) | |

| Rhythmic gymnastics | 8 | 0 (0.0) | 8 (100.0) | |

| Martial arts | 7 | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Fencing | 2 | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Horseback riding | 2 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | |

| Boxing | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Diving | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Skiing | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Wrestling | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | Other | 10 | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) |

| Total | 299 | 208 (69.6) | 91 (30.4) | |

After removing female gymnasts and dancers from the analysis, the relative risk of being highly specialized misclassified as moderate was similar for individual- versus team-sport athletes (RR = 1.02; 95% CI = 0.56, 1.85).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, we are the first to report the proportion of specialized athletes who had only ever played a single sport compared with those who quit previous sports to focus on a main sport. Nearly one-third of the single-sport athletes who trained more than 8 months per year had never played another sport. This proportion was greater than that suggested by a 2010 report12 on National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I intercollegiate female athletes, which showed that 17% of the athletes studied had participated exclusively in their collegiate sport. This may be because our sample likely included a relatively larger proportion of gymnasts and dancers. For sports in which peak performance occurs before puberty, such as women's artistic and rhythmic gymnastics and figure skating, it is common to become involved at a young age and not ever play any other sports.9,13

We also found that these highly specialized misclassified as moderate athletes were more likely to participate in individual sports and to be female. However, being an individual-sport athlete was highly correlated with being a gymnast or dancer, and when we removed these athletes from the analysis, the risk of being misclassified was similar for individual- and team-sport athletes. This suggests that in our study population (and similar pediatric sports medicine clinic populations), the group at greatest risk for misclassification was female gymnasts and dancers. However, we also observed that 33% of soccer athletes were misclassified, so misclassification was not unique to individual sports or to gymnasts and dancers. Future researchers with larger sample sizes of nondancer and nongymnast individual-sport athletes may better evaluate whether athletes in individual sports are at higher relative risk of being misclassified than those in team sports.

A high level of specialization has been independently associated with increased odds of injury, especially overuse and serious overuse injuries, in young athletes.2,3,7,8 Intensive and exclusive training in a single sport at a young age may lead athletes to miss out on the putative benefits of athletic diversification and exposure to a varied set of movement patterns. These benefits include skill transfers among sports and balanced neuromuscular development.3,9 Thus, it may be important to identify this subset of highly specialized athletes with no prior sport experiences as they may be at similar or even greater risk for injury than the highly specialized athletes who were previously exposed to other sports.

Currently, the 3-question specialization survey that includes the question about quitting other sports is widely used as the method of stratifying specialization level in specialization research and literature.2–4,14 Our findings suggest that researchers should consider modifying the commonly used sport-specialization survey to account for athletes who never played other sports. One possibility would be to add a fourth question, “Have you only ever played 1 sport?” Athletes would still be classified as low (0–1 points), moderate (2 points), or high in terms of specialization (3 points), but highly specialized athletes would be divided into those who quit other sports and those who never played other sports. This classification method makes it possible for investigators to evaluate the 2 groups of highly specialized athletes separately, comparing them with one another and with the low- and moderate-specialization groups in descriptive demographics, risk factors, and outcomes. Including this fourth question would allow this unique category of highly specialized athletes to be better studied, especially with regard to injury risk and burnout, as their injury risks may differ from those of highly specialized athletes who previously played other sports.

LIMITATIONS

Our study had several limitations. First, we assumed that most experts in the area of sport specialization would consider an athlete who trained more than 8 months per year in a single sport to be highly specialized, whether the athlete had quit other sports to focus on a main sport or had never played any other sports. This study was performed using self-reported data from the athletes and parents, and therefore is subject to recall bias. Selection bias was also possible because the sample consisted only of athletes who sought care for injuries from a single sports medicine specialist's clinic in the Midwest. Further selection bias may have been present due to this specialist's expertise in treating gymnasts and dancers. However, even so, a large variety of sports were represented, and misclassification was not exclusive to female gymnasts and dancers.

CONCLUSIONS

The commonly used 3-question survey to classify an athlete's degree of sport specialization misclassified approximately 30% of highly specialized athletes as moderately specialized. Researchers studying the benefits and risks of sports specialization should consider adding a fourth question, “Have you only ever played 1 sport?” This would identify and allow for better study of this unique subset of highly specialized athletes who have never been exposed to other sports.

Appendix.

Sports-participation history.

REFERENCES

- 1.DiFiori JP, Benjamin HJ, Brenner J, et al. Overuse injuries and burnout in youth sports: a position statement from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(4):287–288. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell DR, Post EG, Trigsted SM, Hetzel S, McGuine TA, Brooks MA. Prevalence of sport specialization in high school athletics: a 1-year observational study. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1469–1474. doi: 10.1177/0363546516629943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jayanthi NA, LaBella CR, Fischer D, Pasulka J, Dugas LR. Sports-specialized intensive training and the risk of injury in young athletes: a clinical case-control study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):794–801. doi: 10.1177/0363546514567298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGuine TA, Post EG, Hetzel SJ, Brooks MA, Trigsted SM, Bell DR. A prospective study on the effect of sport specialization on lower extremity injury rates in high school athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(12):2706–2712. doi: 10.1177/0363546517710213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasulka J, Jayanthi N, McCann A, Dugas LR, LaBella C. Specialization patterns across various youth sports and relationship to injury risk. Phys Sportsmed. 2017;45(3):344–352. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2017.1313077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks MA, Post EG, Trigsted SM, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of youth club athletes toward sport specialization and sport participation. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(5):2325967118769836. doi: 10.1177/2325967118769836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall R, Barber Foss K, Hewett TE, Myer GD. Sport specialization's association with an increased risk of developing anterior knee pain in adolescent female athletes. J Sport Rehabil. 2015;24(1):31–35. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2013-0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell DR, Post EG, Biese K, Bay C, Valovich McLeod T. Sport specialization and risk of overuse injuries: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3):ii.:e20180657. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0657. p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Côté J, Lidor R, Hackfort D. ISSP position stand: to sample or to specialize? Seven postulates about youth sport activities that lead to continued participation and elite performance. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2009;7(1):7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stracciolini A, Casciano R, Levey Friedman H, Stein CJ, Meehan WP, III, Micheli LJ. Pediatric sports injuries: a comparison of males versus females. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(4):965–972. doi: 10.1177/0363546514522393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buckley PS, Bishop M, Kane P, et al. Early single-sport specialization: a survey of 3090 high school, collegiate, and professional athletes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(7):232596711703944. doi: 10.1177/2325967117703944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malina RM. Early sport specialization: roots, effectiveness, risks. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2010;9(6):364–371. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181fe3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law MP, Côté J, Ericsson KA. Characteristics of expert development in rhythmic gymnastics: a retrospective study. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2007;5(1):82–103. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jayanthi NA, Holt DB, Jr, LaBella CR, Dugas LR. Socioeconomic factors for sports specialization and injury in youth athletes. Sports Health. 2018;10(4):303–310. doi: 10.1177/1941738118778510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]