Lactobacillus casei Zhang is a probiotic that confers beneficial effects on the host, and it is thus increasingly used in the dairy industry. The possession of an effective bacterial immune system that can defend against invasion of phages and exogenous DNA is a desirable feature for industrial bacterial strains. The bacteriophage exclusion (BREX) system is a recently described phage resistance system in prokaryotes. This work confirmed the function of the BREX system in L. casei and that the methyltransferase (pglX) is an indispensable part of the system. Overall, our study characterizes a BREX system component gene in lactic acid bacteria.

KEYWORDS: Lactobacillus casei Zhang, bacteriophage exclusion system, BREX, methyltransferase, MTase, pglX

ABSTRACT

The bacteriophage exclusion (BREX) system is a novel prokaryotic defense system against bacteriophages. To our knowledge, no study has systematically characterized the function of the BREX system in lactic acid bacteria. Lactobacillus casei Zhang is a probiotic bacterium originating from koumiss. By using single-molecule real-time sequencing, we previously identified N6-methyladenine (m6A) signatures in the genome of L. casei Zhang and a putative methyltransferase (MTase), namely, pglX. This work further analyzed the genomic locus near the pglX gene and identified it as a component of the BREX system. To decipher the biological role of pglX, an L. casei Zhang pglX mutant (ΔpglX) was constructed. Interestingly, m6A methylation of the 5′-ACRCAG-3′ motif was eliminated in the ΔpglX mutant. The wild-type and mutant strains exhibited no significant difference in morphology or growth performance in de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) medium. A significantly higher plasmid acquisition capacity was observed for the ΔpglX mutant than for the wild type if the transformed plasmids contained pglX recognition sites (i.e., 5′-ACRCAG-3′). In contrast, no significant difference was observed in plasmid transformation efficiency between the two strains when plasmids lacking pglX recognition sites were tested. Moreover, the ΔpglX mutant had a lower capacity to retain the plasmids than the wild type, suggesting a decrease in genetic stability. Since the Rebase database predicted that the L. casei PglX protein was bifunctional, as both an MTase and a restriction endonuclease, the PglX protein was heterologously expressed and purified but failed to show restriction endonuclease activity. Taken together, the results show that the L. casei Zhang pglX gene is a functional adenine MTase that belongs to the BREX system.

IMPORTANCE Lactobacillus casei Zhang is a probiotic that confers beneficial effects on the host, and it is thus increasingly used in the dairy industry. The possession of an effective bacterial immune system that can defend against invasion of phages and exogenous DNA is a desirable feature for industrial bacterial strains. The bacteriophage exclusion (BREX) system is a recently described phage resistance system in prokaryotes. This work confirmed the function of the BREX system in L. casei and that the methyltransferase (pglX) is an indispensable part of the system. Overall, our study characterizes a BREX system component gene in lactic acid bacteria.

INTRODUCTION

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect and live in bacteria, and they are among the most abundant organisms on Earth (1). Host-parasite coevolution between bacteria and phages has promoted the formation of various phage resistance strategies (2, 3). The bacterial defense strategies against bacteriophage infection can be classified into three general categories: (i) variation of virus receptors, (ii) immunity, and (iii) dormancy induction and programmed cell death (4, 5). The first category includes phase variation and receptor physical masking (6, 7). The second category is relatively well studied. Innate immunity systems, e.g., the restriction-modification (R-M) system, and adaptive immunity systems, e.g., clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas, exist widely among bacteria and are common bacterial defense mechanisms (8, 9). The third category involves the induction of dormancy or programmed cell death, including the toxin-antitoxin systems and the abortive infection systems (10, 11).

Genes coding for the phage defense systems are usually gathered within the bacterial genome to form specific genomic “defense islands” (12). There is an innate immunity system called phage growth limitation (Pgl) embedded within the defense islands in some Streptomyces coelicolor strains, in which the pglZ gene of the phage growth limitation system is centered (13, 14). The pglZ gene is a putative member of the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. In addition, this system also contains a gene encoding an adenine-specific DNA methyltransferase (MTase), namely, pglX, and two additional genes, encoding a putative protein containing a serine/threonine kinase domain, pglW, and a putative protein containing a P-loop domain, pglY (14). Bacteria carrying the pgl system are sensitive to the first cycle of phage infection but are resistant to subsequent cycles. Goldfarb et al. later described a novel bacteriophage defense system, bacteriophage exclusion (BREX), in Bacillus cereus, which is an immunity system that contains a six-gene cassette (15). The type I BREX systems are composed of pglZ and pglX together with four other gene components, namely, brxABCL, which encode an RNA-binding antitermination protein (BrxA), a protein of unknown function (BrxB), an ATP-binding protein (BrxC), and a putative protease (BrxL), respectively. These systems use DNA methylation of the host cell for self-protection and discrimination of self from nonself and inhibit phage DNA replication when the phage lacks methylation at the pglX recognition site (15). BREX family defense systems are found in approximately 10% of bacterial and archaeal genomes, including lactic acid bacteria (15). To our knowledge, very few studies have reported the existence and physiological role of the BREX system in lactic acid bacteria, except for a recent work that found mutations of the BREX-1 system adenine-specific DNA MTase gene in a freeze-thaw-tolerant Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG mutant isolated from an adaptive laboratory evolution experiment (16). Thus, it would be interesting to systematically characterize the biological role of the BREX system of lactic acid bacteria.

Lactobacillus casei is one of the most studied species among lactic acid bacteria due to its wide commercial, industrial, and health-promoting potentials (17). This species is found naturally in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of both adults and infants (18). Lactobacillus casei Zhang is a strain isolated from koumiss, a traditional fermented mare milk product commonly consumed in Inner Mongolia. This isolate has been fully characterized, and it exhibits outstanding probiotic characteristics (19). It also has high tolerance to low-pH environments (20) and bile (21) as well as a high GI colonization capacity (22), making it a good candidate for probiotics. Our previous work reported N6-methyladenine (m6A) signatures in the genome of L. casei Zhang using single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing. Further analysis identified 5′-ACRCAG-3′ as the recognition sequence for the N6-methyladenine MTase, which modified the fifth base of the motif sequence (23). Moreover, the N6-methyladenine MTase gene is homologous to the pglX genes of other BREX systems.

This work aimed to identify the methyltransferase that produces the 5′-ACRCm6AG-3′ modification observed in the Gram-positive probiotic strain L. casei Zhang using a combination of genetic technique and SMRT sequencing. Particularly, a pglX gene disruption mutant was created. Next, the phenotype of the m6A modification mutant was analyzed at the methylome level and by a series of plasmid transformation experiments. Furthermore, the pglX gene was cloned, expressed, and purified using the Escherichia coli expression system to evaluate its in vitro activity.

RESULTS

The genome of L. casei Zhang contains a putative BREX system and a pglX gene.

Previously, m6A methylation was observed in a genome-wide methylome analysis of L. casei Zhang using SMRT sequencing, and 5′-ACRCm6AG-3′ was identified as the m6A recognition motif (23). Thus, bioinformatic analysis was performed using Glimmer and BLAST against the nonredundant database to identify homologous genes in the L. casei Zhang genome that encoded a putative N6-adenine-specific MTase (23). The results of our gene homology search identified a complete cassette of a classic type I BREX system: brxA (LCAZH_2059), brxB (LCAZH_2058), brxC (LCAZH_2057), pglX (LCAZH_2056) (a putative N6-adenine-specific MTase), pglZ (LCAZH_2053), and brxL (LCAZH_2052) (Fig. 1). The identified BREX system had an insertion of two genes between pglX and pglZ. These two inserted genes were int (LCAZH_2055) (a putative phage integrase) and LCAZH_2054 (a putative DNA MTase). To decipher the function of the predicted pglX gene and its role in the BREX system of L. casei Zhang, a gene disruption mutant (L. casei Zhang ΔpglX) was constructed using the cre-loxP gene deletion system.

FIG 1.

Schematic diagram showing the multigene bacteriophage exclusion (BREX) loci in Lactobacillus casei Zhang. The classic type I BREX cassette includes brxA (LCAZH_2059), brxB (LCAZH_2058), brxC (LCAZH_2057), pglX (LCAZH_2056) (a putative N6-adenine-specific MTase), pglZ (LCAZH_2053), and brxL (LCAZH_2052). The identified BREX system had an insertion of two genes between pglX and pglZ, namely, int (LCAZH_2055) (a putative phage integrase) and LCAZH_2054 (a putative DNA MTase).

Obliteration of m6A methylation in the L. casei Zhang ΔpglX genome.

The methylome of L. casei Zhang ΔpglX was sequenced by using SMRT sequencing technology to identify the methylation status of the mutant strain. A total of 87,920 reads (mean read length of 8,868) were generated, representing 779,682,369 bases and 214-fold coverage.

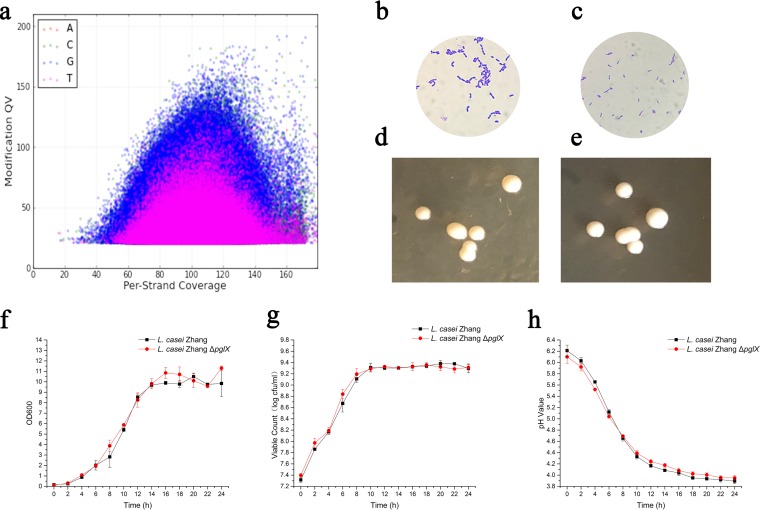

No distinct cloud of modified bases was observed in the DNA modification-versus-coverage scatterplot (Fig. 2a), suggesting that no 5′-ACRCm6AG-3′ methylation occurred in the genome of the mutant strain. Therefore, the disruption of the pglX gene corresponded to the m6A methylation phenotype of wild-type L. casei Zhang, and the pglX gene coded for an MTase that belonged to the BREX system.

FIG 2.

(a) Scatterplot of the modification quality value (QV) versus per-strand coverage in Lactobacillus casei Zhang ΔpglX. (b to e) Gram-stained cells and colony morphology of L. casei Zhang wild-type (b and d) and ΔpglX mutant (c and e) strains. Cell morphology was viewed at a ×1,000 magnification. (f to h) Growth curves of L. casei Zhang wild-type and ΔpglX mutant strains in MRS broth. Shown are changes in the OD600 (f), viable counts (g), and pHs (h). Error bars represent standard deviations.

Disruption of pglX does not alter cell morphology and growth.

To assess the biological role of methylation in bacterial growth, the bacterial morphology and growth of the wild-type and mutant strains in de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) medium were compared. No apparent difference was observed in the microscopic morphology of Gram-stained cells or in the colony morphology on MRS agar (Fig. 2b to e). Moreover, no significant difference was observed in growth performance based on the bacterial cell density reflected by the absorbance, viable count, and pH values in the culture medium (Fig. 2f to h).

pglX plays a significant role in blocking invading plasmids and their maintenance.

As part of the putative BREX system, pglX might function to protect bacterial cells from invading plasmids. Thus, the abilities of the wild-type and mutant strains to block and restrict exogenous plasmids were compared by plasmid transformation assays. Three E. coli-Lactobacillus shuttle plasmids that contained the pglX recognition motif, pMSP3535, pTRKH2, and pNZ5348, were included, and in each case, the L. casei Zhang ΔpglX strain exhibited a significantly higher transformation efficiency than the wild type (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3a to c). The mean transformation efficiency values are shown in Table 1. Next, a second experiment was performed to monitor the stability of the transformed plasmids (pMSP3535 or pTRKH2) in the two bacterial cell lines, and the results showed that the transformed plasmids were generally more stable in wild-type cells than in L. casei Zhang ΔpglX cells beyond 12 h of growth (Fig. 3d and e). The differences in plasmid retention between the two cell lines were even more obvious as growth proceeded; significant differences were observed at 96 h (P < 0.01) and 84 h (P < 0.01) for plasmids pMSP3535 and pTRKH2, respectively. These results together suggested that the pglX gene played a crucial role in conferring resistance against exogenous genetic materials and their maintenance.

FIG 3.

(a to c) Plasmid transformation efficiencies of Lactobacillus casei Zhang wild-type and mutant strains. Zhang is the wild type, and Zhang ΔpglX is the mutant strain. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s unpaired two-tailed t test. Double asterisks represent significant differences (P < 0.01). (d and e) Stability of plasmids pMSP3535 (d) and pTRKH2 (e) in Lactobacillus casei Zhang wild-type and ΔpglX mutant strains. Error bars represent standard deviations.

TABLE 1.

Transformation efficiencies

| Plasmid | Mean transformation efficiency (CFU/μg plasmid DNA) for straina |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang | Zhang ΔpglX | Zhang-pleiss | Zhang ΔpglX-pleiss | Zhang ΔpglX-pglX | |

| pMSP3535 | 1.01 × 105 | 2.25 × 105 | 2.6 × 103 | 2.25 × 104 | 1.23 × 104 |

| pTRKH2 | 31.5 | 1.88 × 102 | |||

| pNZ5348 | 22.5 | 7.7 × 103 | |||

| pSec:Leiss:Nuc | 7.65 × 105 | 1.08 × 106 | |||

| pG+host9 | 7.45 × 106 | 8.1 × 106 | 7.47 × 103 | 2.86 × 103 | 6.12 × 103 |

Zhang is the wild-type strain, Zhang ΔpglX is the mutant strain, Zhang-pleiss is the wild-type strain with plasmid pSec:Leiss:Nuc, Zhang ΔpglX-pleiss is the mutant strain with plasmid pSec:Leiss:Nuc, and Zhang ΔpglX-pglX is the complemented strain.

The recognition site sequence is necessary for pglX gene function.

To further characterize the functional requirement of the pglX gene for defense against foreign plasmids, specifically if a recognition site sequence was necessary for its function, two plasmids, pSec:Leiss:Nuc and pG+host9, that had no 5′-ACRCAG-3′ site were used in the plasmid transformation assays. No significant difference was observed in the plasmid transformation efficiencies between the wild-type and ΔpglX strains for both plasmids (Fig. 4). Next, the wild-type (Zhang-pleiss) and L. casei Zhang ΔpglX (Zhang ΔpglX-pleiss) strains, which carried the plasmid pSec:Leiss:Nuc, as well as the pglX-complemented ΔpglX mutant (Zhang ΔpglX-pglX) were transformed with pMSP3535 (containing the pglX recognition sequence) and pG+host9 (without the pglX recognition sequence). The restriction of pMSP3535 was partially restored for the complemented strain, while no significance difference was observed in the transformation efficiencies of pG+host9 among the three strains (Fig. 5). These results together suggested that plasmid blocking and restriction were conferred by the pglX gene and that pglX recognition was required for such functions.

FIG 4.

Plasmid transformation efficiencies of Lactobacillus casei Zhang wild-type and mutant strains. Zhang is the wild type, and Zhang ΔpglX is the mutant strain. Error bars represent standard deviations.

FIG 5.

Plasmid transformation efficiencies of the Lactobacillus casei Zhang wild-type strain with plasmid pSec:Leiss:Nuc (Zhang-pleiss), the mutant strain with plasmid pSec:Leiss:Nuc (Zhang ΔpglX-pleiss), and the complemented strain (Zhang ΔpglX-pglX). Error bars represent standard deviations. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s unpaired two-tailed t test. Double asterisks represent significant differences (P < 0.01).

Recombinant PglX protein exhibits no restriction endonuclease activity.

The Rebase database (24) predicted that the PglX protein could be a bifunctional enzyme that possesses dual activities, as both a restriction endonuclease and an MTase. To verify this prediction, the pglX gene was first cloned into an E. coli expression plasmid to construct pET-pglX, which was then heterologously expressed in E. coli DE3. The recombinant PglX protein containing a C-terminal 6 histidine tag was sequentially purified by nickel affinity chromatography and gel filtration chromatography. Analysis of the purified protein fraction by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) revealed a single protein band with a molecular mass positioned between 100 and 150 kDa (Fig. 6a), matching the theoretical molecular mass of the predicted recombinant protein of 138 kDa.

FIG 6.

(a) SDS-PAGE analysis of overexpressed PglX protein. Lane M, protein marker; lane DE3/pglX, crude extract of pET-pglX-transformed E. coli DE3; lane PglX, purified PglX protein. (b) Endonuclease activity of purified PglX protein λ DNA. Lane M, λ-HindIII digestion DNA marker; lane B, λ DNA digested with buffer only; lane C, λ DNA digested with the crude extract of pET-pglX-transformed E. coli DE3; lane P, λ DNA digested with recombinant PglX protein.

The endonuclease activity of the purified PglX protein was then assayed using λ DNA as the substrate. The λ DNA was degraded by the whole-cell extract of pET-pglX-transformed E. coli but not the purified recombinant protein, suggesting that the PglX protein did not exhibit endonuclease activity (Fig. 6b).

DISCUSSION

The development of the PacBio SMRT sequencing technology has facilitated genome-wide methylome analysis by overcoming technical barriers in studying m6A and N4-methylcytosine (m4C) modifications in prokaryotes (25). By using such technology, our laboratory previously performed a genome-wide methylome analysis of the probiotic strain L. casei Zhang. Our results revealed 1,906 m6A methylation sites in the bacterial genome, and 5′-ACRCm6AG-3′ was identified as the m6A recognition motif. Meanwhile, in the genome of L. casei Zhang, a putative N6-methyladenine MTase was identified (23). Here, we analyze the nature and function of the putative N6-methyladenine MTase by performing further bioinformatic analysis, construction and characterization of the ΔpglX mutant, and heterologous expression of the predicted protein.

Further bioinformatic analysis revealed a high degree of homology between the putative N6-methyladenine and the pglX genes of the type I BREX systems. By analyzing the upstream and downstream genomic locations of this putative pglX sequence, a complete cassette of the BREX system could be identified. Such a cassette has been described in other prokaryotes, e.g., Bacillus and E. coli, as a six-gene cassette, containing an alkaline phosphatase (pglZ) and an MTase (pglX) as well as brxABCL, which encode a NusB-like RNA-binding protein (brxA), an unknown small protein (brxB), an ATP-binding protein (brxC), and a Lon-like protease (brxL) (15). Unlike the BREX system of some other bacteria, the BREX system of L. casei Zhang seems to be an eight-gene cassette. In addition to pglZ, pglX, and brxABCL, an integrase gene (int) and a relatively small MTase gene (LCAZH_2054) are embedded between the pglX and pglZ genes and are oriented in the opposite direction from the rest of the BREX system. Based on the high sequence homology with other MTases, we speculate that the LCAZH_2054 gene could play a supporting role in the bacterial methylation process together with the pglX gene, potentially conferring wider substrate specificity by swapping with the pglX gene via the action of the embedded integrase (int) (15). However, the exact roles of the LCAZH_2054 and int genes remain to be experimentally verified. Since the acquisition of the BREX system genes relies on horizontal gene transfer, the distinctive gene makeup of the BREX system of L. casei Zhang might indicate various degrees of diversity among bacteria and archaea and that unique evolutionary events occurred during BREX system gene acquisition among lactic acid bacteria.

In order to assess the biological function of the pglX gene, the ΔpglX mutant was constructed and characterized by SMRT sequencing. Interestingly, SMRT sequencing did not detect any m6A methylation in the mutant, in contrast to the 1,906 m6A methylation sites in the wild-type parent revealed by our previous work (23). Such results strongly support that the identified L. casei Zhang pglX gene encoded an adenine MTase, which was consistent with the results of genome annotation and prediction based on sequence homology. We then explored the role of m6A methylation in bacterial growth and maintenance.

Generally, bacterial DNA MTases play important roles in regulating basic cell biological processes (26). They not only are involved in the R-M systems but also serve as cell cycle regulators that control fundamental processes like chromosome replication, transcription, and repair (27). In pathogens such as Salmonella, Haemophilus, Yersinia, Vibrio, and pathogenic E. coli, DNA adenine methylation facilitates the expression of bacterial virulence phenotypes (27, 28). Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium mutant cells that lacked adenine MTase showed diminished growth and asynchronous replication, supporting the role of this protein in cell growth regulation (29). However, in our study, we observed that the pglX mutant only lost its capacity for m6A modification at the 5′-ACRCAG-3′ motif but exhibited no apparent change in colony morphology, cell morphology, and growth performance in MRS culture medium in comparison with the wild-type strain. Such results might suggest that the biological role of DNA methylation is species and/or strain specific.

We then performed a series of plasmid transformation experiments to characterize the cellular function of L. casei Zhang pglX. The pglX mutant and wild-type strains were first transformed with pMSP3535 (containing one recognition site on each DNA strand), pTRKH2 (containing one recognition site on the top strand), and pNZ5348 (only a partial sequence was available, containing at least one recognition site on the top strand). Our results showed that when transforming plasmids that contained pglX recognition sequences, the plasmid acquisition capacity of the mutant strain was always much higher than that of the wild-type strain, suggesting that the loss of the m6A MTase pglX led to a decreased capacity of mutants to block and/or restrict the invading plasmids. A recent study revealed that the MTase is essential for BREX function; inactivating such a gene would obliterate the activity of the BREX system (30). Moreover, the insertion of the BREX gene cassette into Bacillus subtilis conferred bacterial resistance to phage infection, while inactivating pglX rendered the strain sensitive to phage infection (15). The pglX gene played a similar role in the BREX system of E. coli, and deleting such a gene in E. coli abolished the phage protection function (30). Thus, our results provide further evidence that L. casei Zhang pglX is an important component of the BREX system. On the other hand, the disruption of the m4C MTase in Helicobacter pylori and the mutant strains exhibited a reduced capacity for natural transformation (31), which was in contrast to the current results. These contrasting effects might reflect different cellular functions of methylation signals directed by specific MTase genes.

Another plasmid transformation assay was then performed using two other plasmids, namely, pSec:Leiss:Nuc and pG+host9, which did not contain any target sequence of pglX. For both plasmids, no significant difference was observed in the transformation efficiencies between the wild-type and the pglX mutant strains. These results together suggested that the specific target sequence was necessary for conferring the resistance function of the pglX gene in the BREX system to distinguish between self and nonself DNA materials. We then hypothesized that the reduction of DNA methylation might decrease the genetic stability of host cells. To test this hypothesis, the plasmids pMSP3535 and pTRKH2 were transformed into the wild type and the pglX mutant, and their stabilities in the two cell lines were compared. Our results showed that the pglX mutant had a lower capacity to retain the plasmids than the wild-type strain in both cases. The curing of plasmids would depend on factors such as the copy number; however, the same conditions were applied in the plasmid transformation assays, and transformations of the wild-type and mutant strains were performed in parallel. Thus, the difference in plasmid retention capacities between the wild-type and pglX mutant strains was likely due to loss of methylation. Particularly, it is known that adenine methylation plays a role in regulating DNA double-helix formation by controlling base pair stability and base stacking, as shown in previous research (32, 33).

Based on the prediction of the Rebase database (24), the PglX protein could be a dual-function enzyme, acting as both a restriction endonuclease and an MTase. To explore whether the PglX protein acted as a restriction endonuclease, it was heterologously expressed using the E. coli T7 expression system, and its endonuclease activity was assayed. Initially, the complete gene was cloned into a vector that contained an N-terminal 6-histidine tag. However, the purified recombinant proteins appeared as multiple bands on the SDS gel as detected by an anti-histidine tag antibody (data not shown), suggesting degradation of the recombinant protein. Next, the pglX gene was cloned into another plasmid that contained a C-terminal 6-histidine tag, and downstream purification yielded a single-band product that corresponded to the predicted size of the designated protein. The purified PglX protein did not exhibit any DNA restriction activity in an endonuclease assay using λ DNA as the substrate. λ DNA was used as the substrate as it embedded 52 ACRCAG target sites on its genome sequence. Many type II R-M systems recognize palindromic sequences, while some type II subtype R-M systems recognize nonpalindromic sequences (34). In R-M systems, the methyltransferases usually have a cognate restriction enzyme, or in some cases, they may exert both restriction and modification functions within a single polypeptide, such as the enzymes MmeI (35) and HaeIV (36). However, we failed to identify any cognate restriction enzyme or restriction enzyme domain within the L. casei Zhang genome and its coding sequence. The current results show that the PglX protein functions solely as an adenine MTase rather than a bifunctional protein that possessed endonuclease activity.

Few studies have systematically characterized the function of the BREX system in lactic acid bacteria. The bioinformatic analysis of this work revealed a putative BREX system in the probiotic bacterial strain L. casei Zhang. By using a combination of a reverse genetic technique, SMRT sequencing, plasmid transformation assays, and heterologous expression and functional assays of the purified recombinant PglX protein, this work confirmed that the L. casei Zhang pglX gene product is a functional adenine MTase that is an essential component of a type I BREX system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, bacterial strains, and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. The bacterial strain L. casei Zhang was isolated from a traditional dairy product, koumiss, of Inner Mongolia, China. The bacteria were propagated in de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) anaerobically at 37°C. E. coli DH5α was used as the host for plasmid cloning. E. coli DE3 was used as the host for overexpression of the pglX gene. All E. coli strains were grown aerobically in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C. For E. coli strains, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and erythromycin were used at concentrations of 100 μg/ml, 10 μg/ml, and 300 μg/ml, respectively. Chloramphenicol and erythromycin were used at a concentration of 5 μg/ml in MRS broth for L. casei strains when necessary.

TABLE 2.

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this studya

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Description or primer sequence | Reference, source, or restriction enzyme site |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Lactobacillus casei | ||

| Zhang | Wild-type strain | |

| Zhang γ456 | L. casei Zhang with plasmid pMSPγ456 | This study |

| Zhang ΔpglX | pglX gene mutant strain | This study |

| Zhang-pleiss | Wild-type strain with plasmid pSec:Leiss:Nuc | This study |

| Zhang ΔpglX-pleiss | pglX gene mutant strain with plasmid pSec:Leiss:Nuc | This study |

| Zhang ΔpglX-pglX | pglX gene mutant strain with pglX expression plasmid pLEISS-pglX | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | Subcloning host | Novagen |

| XL1-Blue | Subcloning host | Novagen |

| DE3 | Expression host | Novagen |

| DE3/Pet | DE3 with pET22b | This study |

| DE3-pglX | DE3 with pET-pglX | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pNZ5319 | Cmr Emr; containing lox66-P32-cat-lox71 cassette for multiple-gene replacement in Gram-positive bacteria | 38 |

| pNZ5319-pglX | Cmr Emr; pNZ5319 derivative containing homologous regions up- and downstream of pglX | This study |

| pMSP456γ | pMSP3535 derivative; expresses Gam and LCABL_13040-50-60 under PnisA control | 39 |

| pMSPcre | pMSP3535 derivative; expresses Cre under PnisA control | 39 |

| pMSP3535 | Ermr | 41 |

| pTRKH2 | Ermr | 42 |

| pNZ5348 | Ermr | 38 |

| pSec:Leiss:Nuc | Cmr | 43 |

| pLEISS-pglX | Cmr; pSec:Leiss:Nuc derivative; pglX expression plasmid | This study |

| pG+host9 | Ermr | 44 |

| pET22b | Apr; carries the T7 promoter and lac operator | Novagen |

| pET-pglX | Apr; expresses the PglX protein under T7 promoter control | This study |

| Primers | ||

| upF | TATCTCGAGTTTGGCGCTTGATGAA | XhoI |

| upR | CTATTTAAATGAGTGCTCCTTTCAACGCCG | SwaI |

| downF | GGGTTTGAGCTCTCAAAAAGGGCGATCCCCAGTTGAG | Eco53KI |

| downR | GAAGATCTTTTTGAGTTTTGTGACAAATATGTG | BglII |

| NdeIpglXF | GGAATTCCATATGGATAAAAAAGCTATCAAAACAT | NdeI |

| XhoIpglXR | CCGCTCGAGCTTTAATGGTGTCAAAATTTTTGTA | XhoI |

| BglII-proF | CAAGATCTTCCATGATGGC | BglII |

| proR | AGTTGATCTCCTTTCCAAGTTT | |

| pro-pglXF | GAAAGGAGATCAACTATGGATAAAAAAGCTATCAAAACA | |

| XhoI-pglXR | CCGCTCGAGTCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGCTTTAATGGTGTCAAAATTT | XhoI |

Cmr, Emr, and Apr indicate chloramphenicol, erythromycin, and ampicillin resistance, respectively. Underlining in sequences indicates the restriction enzyme site.

Reagents and standard procedures used for creating L. casei mutants.

Primers used for PCR amplification of the pglX gene-flanking sequences are listed in Table 2. Flanking sequence fragments were amplified by using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher) and 2*PrimeSTAR max premix (TaKaRa). Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from TaKaRa Ltd. Plasmid extraction was achieved by using a plasmid minikit (Omega). A gel extraction kit (Omega) or Cycle-Pure kit (Omega) was used for linear DNA purification. All molecular manipulations in this study were performed using established procedures (37). All reagents were used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Generation of a linear DNA homology fragment.

To inactivate the L. casei Zhang pglX gene, a linear DNA homology fragment that contained a chloramphenicol resistance gene marker flanked by the upstream and downstream sequences of the pglX gene was prepared. The flanking sequences of the pglX gene were amplified from the genomic DNA extracted from L. casei Zhang as the template using primers targeting the upstream (upF and upR) and downstream (downF and downR) pglX sequences. The amplified flanking sequences were purified and cloned into suitable sites of the vector pNZ5319 (38), containing a lox66-cat-lox71 cassette, to generate the upstream-lox66-cat-lox71-downstream cassette. The linear homology fragment was further generated by PCR amplification with the primers upF and downR using the upstream-lox66-cat-lox71-downstream plasmid as the template.

Construction of a pglX gene disruption mutant.

The prophage-derived recombinase expression plasmid pMSP456γ combined with the cre-lox system was used to generate the pglX gene disruption mutant (39). The plasmid pMSP456γ was introduced into L. casei Zhang by using an electroporator. Transformants were confirmed by erythromycin selection and PCR (39). L. casei Zhang harboring pMSP456γ was propagated in 5 ml MRS broth containing 1% glycine and 0.75 M sorbitol. When the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the growing culture reached 0.25 to 0.30, a final concentration of 5 ng/ml of nisin was added to induce the production of prophage-derived recombinase. Electrocompetent cells were prepared when the OD600 reached 0.60 to 0.65. The linear DNA homology fragments were transformed into competent cells by electroporation. Cells were plated on a chloramphenicol-containing MRS agar plate after recovery at 37°C for 1 h. Target mutants in which the pglX gene had been replaced with lox66-cat-lox71 were selected. In order to excise the selectable marker cassette, the Cre expression plasmid pMSPcre was transformed into the lox66-cat-lox71 mutant. Next, 10 ng/ml nisin was added when the OD600 of the mutant culture reached 0.40 to 0.80 to induce Cre recombinase expression. Subsequently, the cells were spread onto an MRS plate, and mutants without the selectable marker were verified by PCR. The vector pMSPcre was cured from the pglX disruption mutant by growth in culture medium without erythromycin.

Single-molecule real-time sequencing.

The genomic DNA of the mutant strain L. casei Zhang ΔpglX was extracted using the QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of DNA was analyzed by using 0.75% agarose gel electrophoresis, a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer, and a Qubit fluorometer. After the DNA quality check, Covaris g-Tube was used to randomly fragment the genomic DNA. Sheared DNA fragments were end repaired and ligated to hairpin adapters. Unligated fragments were digested with exonuclease. Before sequencing, the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer high-sensitivity kit was used to assess the quality of the produced library. Sequencing was performed with P6-C4 chemistry on a PacBio RS II instrument (Pacific Biosciences).

Methylome analysis.

Methylation of the genomic DNA of L. casei Zhang ΔpglX was analyzed by using the Pacific Biosciences SMRT Portal analysis platform. The −10 log(P value) was set as modQV, which represented a modified base position. The default setting of the modQV threshold was 20, which corresponded to a P value of 0.01. The RS_Modification_and_Motif_Analysis.1.4 protocol was selected to identify methylation positions and motifs on the bacterial genome (40).

Growth curve construction.

Growth curves of the wild-type and ΔpglX mutant strains were constructed by recording bacterial growth in MRS broth. The optical density, pH, and number of viable bacteria were monitored at 2-h intervals over a 24-h period. All analyses were performed in triplicate.

Plasmid transformation efficiency and stability.

To compare the plasmid transformation efficiencies of the wild-type and mutant strains, competent cells were prepared when the OD600 of the two strains reached 0.3, i.e., equivalent to a viable count of 107 CFU/ml. Next, 1 μg of either pMSP3535 (41), pTRKH2 (42), pNZ5348 (38), pSec:Leiss:Nuc (43), or pG+host9 (44) was electrotransformed into the competent cells. After recovery, cells were spread on an MRS plate containing erythromycin. The transformation efficiency was expressed as the number of transformants per microgram of DNA. The plasmid stabilities of pMSP3535 and pTRKH2 in the two strains were determined by serial passage of the plasmid-transformed cells in MRS broth, with or without erythromycin, every 12 h for 96 h. After parallel passage, cells were plated out on MRS agar with or without erythromycin, respectively. Plasmid stability was calculated as the percentage of CFU observed after passage in erythromycin-containing MRS broth among CFU grown in MRS broth without antibiotics (45). All analyses were performed in triplicate.

Complementation of the pglX gene.

Gene fragments of the pglX gene and its promoter region (pro) were amplified from the L. casei Zhang genome using the primer pair pro-pglXF and XhoI-pglXR and the primer pair BglII-proF and proR, respectively. XhoI-pglXR contained the sequence of a 6-histidine tag. Next, the promoter and the pglX fragments were fused by overlapping PCR, generating the pro-pglX fragment, which was then digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes (BglII and XhoI) and ligated with the pSec:Leiss:Nuc plasmid restricted by the same enzymes, resulting in the complementary plasmid pLEISS-pglX. pLEISS-pglX was then introduced into the L. casei Zhang ΔpglX mutant to generate the complemented strain L. casei Zhang ΔpglX-pglX. The efficiency of transformation of the plasmids pMSP3535 and pG+Host9 into the L. casei Zhang ΔpglX-pglX strain was assayed as described above, using pSec:Leiss:Nuc-transformed wild-type and L. casei Zhang ΔpglX cells as controls.

Construction of the PglX protein overexpression plasmid.

The pglX gene fragment was generated by PCR (with the primers NdeI2056F and XhoI2056R) using the L. casei Zhang genomic DNA as the template. Next, the amplicon was digested with the restriction enzymes NdeI and XhoI, before being cloned into the corresponding sites of the expression plasmid pET-22b, to generate the plasmid pET-pglX.

Expression and purification of PglX protein.

The plasmid pET-pglX was transformed into E. coli DE3 host cells to generate DE3-pglX. The expression of PglX protein with a C-terminal 6-histidine tag was induced by the addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Sangon, China) at a final concentration of 0.1 mM when the OD600 of E. coli cultures reached 0.8. The induced E. coli cells were grown overnight at 16°C. Next, 0.5 liters of the culture grown overnight was harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 5 min and resuspended in 40 ml Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5). An ultrasonic cell-crushing device was used for cell disruption. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 min. The tagged PglX protein was purified with a 1-ml bed volume in a Ni-Sepharose 6 Fast Flow column (GE Healthcare), followed by a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare). The purified proteins were analyzed by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Endonuclease assay.

The endonuclease activity of the purified PglX protein was assayed. Five microliters of purified PglX protein was added to a final volume of 15 μl of a reaction mix containing 10-fold NEB CutSmart buffer, 300 ng of bacteriophage λ DNA, and molecular-biology-grade water. The reaction mix was incubated at 37°C for 1 h before checking for changes in the DNA band mobility pattern by electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31922071) and the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia (grant no. 2017JQ06).

REFERENCES

- 1.Keen EC. 2015. A century of phage research: bacteriophages and the shaping of modern biology. Bioessays 37:6–9. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Labrie SJ, Samson JE, Moineau S. 2010. Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:317–327. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern A, Sorek R. 2011. The phage-host arms race: shaping the evolution of microbes. Bioessays 33:43–51. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makarova KS, Anantharaman V, Aravind L, Koonin EV. 2012. Live virus-free or die: coupling of antivirus immunity and programmed suicide or dormancy in prokaryotes. Biol Direct 7:40. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-7-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. 2013. Comparative genomics of defense systems in archaea and bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 41:4360–4377. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaturongakul S, Ounjai P. 2014. Phage-host interplay: examples from tailed phages and Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. Front Microbiol 5:442. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyman P, Abedon ST. 2010. Bacteriophage host range and bacterial resistance. Adv Appl Microbiol 70:217–248. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(10)70007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorek R, Kunin V, Hugenholtz P. 2008. CRISPR—a widespread system that provides acquired resistance against phages in bacteria and archaea. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:181–186. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams RJ. 2003. Restriction endonucleases: classification, properties, and applications. Mol Biotechnol 23:225–243. doi: 10.1385/MB:23:3:225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chopin MC, Chopin A, Bidnenko E. 2005. Phage abortive infection in lactococci: variations on a theme. Curr Opin Microbiol 8:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerdes K, Maisonneuve E. 2012. Bacterial persistence and toxin-antitoxin loci. Annu Rev Microbiol 66:103–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Snir S, Koonin EV. 2011. Defense islands in bacterial and archaeal genomes and prediction of novel defense systems. J Bacteriol 193:6039–6056. doi: 10.1128/JB.05535-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chinenova TA, Mkrtumian NM, Lomovskaia ND. 1982. Genetic characteristics of a new phage resistance trait in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Genetika 18:1945–1952. (In Russian.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sumby P, Smith MC. 2002. Genetics of the phage growth limitation (Pgl) system of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol Microbiol 44:489–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldfarb T, Sberro H, Weinstock E, Cohen O, Doron S, Charpak-Amikam Y, Afik S, Ofir G, Sorek R. 2015. BREX is a novel phage resistance system widespread in microbial genomes. EMBO J 34:169–183. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon YW, Bae JH, Kim SA, Han NS. 2018. Development of freeze-thaw tolerant Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG by adaptive laboratory evolution. Front Microbiol 9:2781. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill D, Sugrue I, Tobin C, Hill C, Stanton C, Ross RP. 2018. The Lactobacillus casei group: history and health related applications. Front Microbiol 9:2107. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turroni F, Ventura M, Butto LF, Duranti S, O’Toole PW, Motherway MO, van Sinderen D. 2014. Molecular dialogue between the human gut microbiota and the host: a Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium perspective. Cell Mol Life Sci 71:183–203. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1318-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Guo Z, Zhang Q, Yan L, Chen W, Liu XM, Zhang HP. 2009. Fermentation characteristics and transit tolerance of probiotic Lactobacillus casei Zhang in soymilk and bovine milk during storage. J Dairy Sci 92:2468–2476. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu R, Wang L, Wang J, Li H, Menghe B, Wu J, Guo M, Zhang H. 2009. Isolation and preliminary probiotic selection of lactobacilli from koumiss in Inner Mongolia. J Basic Microbiol 49:318–326. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200800047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu R, Sun Z, Wu J, Meng H, Zhang H. 2010. Effect of bile salts stress on protein synthesis of Lactobacillus casei Zhang revealed by 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis. J Dairy Sci 93:3858–3868. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwok LY, Wang L, Zhang J, Guo Z, Zhang H. 2014. A pilot study on the effect of Lactobacillus casei Zhang on intestinal microbiota parameters in Chinese subjects of different age. Benef Microbes 5:295–304. doi: 10.3920/BM2013.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang W, Sun Z, Menghe B, Zhang H. 2015. Short communication: single molecule, real-time sequencing technology revealed species- and strain-specific methylation patterns of 2 Lactobacillus strains. J Dairy Sci 98:3020–3024. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-9272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts RJ, Vincze T, Posfai J, Macelis D. 2015. REBASE—a database for DNA restriction and modification: enzymes, genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D298–D299. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis BM, Chao MC, Waldor MK. 2013. Entering the era of bacterial epigenomics with single molecule real time DNA sequencing. Curr Opin Microbiol 16:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasu K, Nagaraja V. 2013. Diverse functions of restriction-modification systems in addition to cellular defense. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77:53–72. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00044-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reisenauer A, Kahng LS, McCollum S, Shapiro L. 1999. Bacterial DNA methylation: a cell cycle regulator? J Bacteriol 181:5135–5139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wion D, Casadesus J. 2006. N6-methyl-adenine: an epigenetic signal for DNA-protein interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 4:183–192. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aloui A, Tagourti J, El May A, Joseleau Petit D, Landoulsi A. 2011. The effect of methylation on some biological parameters in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Pathol Biol (Paris) 59:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordeeva J, Morozova N, Sierro N, Isaev A, Sinkunas T, Tsvetkova K, Matlashov M, Truncaite L, Morgan RD, Ivanov NV, Siksnys V, Zeng L, Severinov K. 2019. BREX system of Escherichia coli distinguishes self from non-self by methylation of a specific DNA site. Nucleic Acids Res 47:253–265. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar S, Karmakar BC, Nagarajan D, Mukhopadhyay AK, Morgan RD, Rao DN. 2018. N4-cytosine DNA methylation regulates transcription and pathogenesis in Helicobacter pylori. Nucleic Acids Res 46:3429–3445. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeltsch A, Jurkowska R. 2016. DNA methyltransferases—role and function. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sternglanz H, Bugg CE. 1973. Conformation of N6-methyladenine, a base involved in DNA modification:restriction processes. Science 182:833–834. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4114.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts RJ, Belfort M, Bestor T, Bhagwat AS, Bickle TA, Bitinaite J, Blumenthal RM, Degtyarev S, Dryden DT, Dybvig K, Firman K, Gromova ES, Gumport RI, Halford SE, Hattman S, Heitman J, Hornby DP, Janulaitis A, Jeltsch A, Josephsen J, Kiss A, Klaenhammer TR, Kobayashi I, Kong H, Kruger DH, Lacks S, Marinus MG, Miyahara M, Morgan RD, Murray NE, Nagaraja V, Piekarowicz A, Pingoud A, Raleigh E, Rao DN, Reich N, Repin VE, Selker EU, Shaw PC, Stein DC, Stoddard BL, Szybalski W, Trautner TA, Van Etten JL, Vitor JM, Wilson GG, Xu SY. 2003. A nomenclature for restriction enzymes, DNA methyltransferases, homing endonucleases and their genes. Nucleic Acids Res 31:1805–1812. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Callahan SJ, Luyten YA, Gupta YK, Wilson GG, Roberts RJ, Morgan RD, Aggarwal AK. 2016. Structure of type IIL restriction-modification enzyme MmeI in complex with DNA has implications for engineering new specificities. PLoS Biol 14:e1002442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piekarowicz A, Golaszewska M, Sunday AO, Siwińska M, Stein DC. 1999. The HaeIV restriction modification system of Haemophilus aegyptius is encoded by a single polypeptide. J Mol Biol 293:1055–1065. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2006. The condensed protocols from Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lambert JM, Bongers RS, Kleerebezem M. 2007. Cre-lox-based system for multiple gene deletions and selectable-marker removal in Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:1126–1135. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01473-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xin Y, Guo T, Mu Y, Kong J. 2017. Identification and functional analysis of potential prophage-derived recombinases for genome editing in Lactobacillus casei. FEMS Microbiol Lett 364:fnx243. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng Z, Fang G, Korlach J, Clark T, Luong K, Zhang X, Wong W, Schadt E. 2013. Detecting DNA modifications from SMRT sequencing data by modeling sequence context dependence of polymerase kinetic. PLoS Comput Biol 9:e1002935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bryan EM, Bae T, Kleerebezem M, Dunny GM. 2000. Improved vectors for nisin-controlled expression in gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid 44:183–190. doi: 10.1006/plas.2000.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Sullivan DJ, Klaenhammer TR. 1993. High- and low-copy-number Lactococcus shuttle cloning vectors with features for clone screening. Gene 137:227–231. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90011-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ribeiro LA, Azevedo V, Le Loir Y, Oliveira SC, Dieye Y, Piard JC, Gruss A, Langella P. 2002. Production and targeting of the Brucella abortus antigen L7/L12 in Lactococcus lactis: a first step towards food-grade live vaccines against brucellosis. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:910–916. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.2.910-916.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biswas I, Gruss A, Ehrlich SD, Maguin E. 1993. High-efficiency gene inactivation and replacement system for gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol 175:3628–3635. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3628-3635.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mosrati R, Nancib N, Boudrant J. 1993. Variation and modeling of the probability of plasmid loss as a function of growth rate of plasmid-bearing cells of Escherichia coli during continuous cultures. Biotechnol Bioeng 41:395–404. doi: 10.1002/bit.260410402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]