Abstract

Time-lapse imaging reveals a nuanced role for p21 in cancer cells challenged with chemotherapeutic drugs: cells with either high or low p21 are biased toward senescence, whereas intermediate p21 allows cells to re-enter the cell cycle after drug treatment.

Traditional chemotherapies cause high amounts of DNA damage to induce cell death or senescence, a state of permanent cell-cycle withdrawal, but often fail to fully eliminate tumor burden due to heterogeneity in drug response. While many cells die or enter senescence following chemotherapy, a subpopulation of cells may somehow evade these fates and begin proliferating again to cause tumor regrowth. In this issue of Cell, Hsu et al. investigate the proliferation-senescence decision in response to chemotherapy and elucidate how early p21 dynamics predict and shape cellular fate (Hsu et al., 2019).

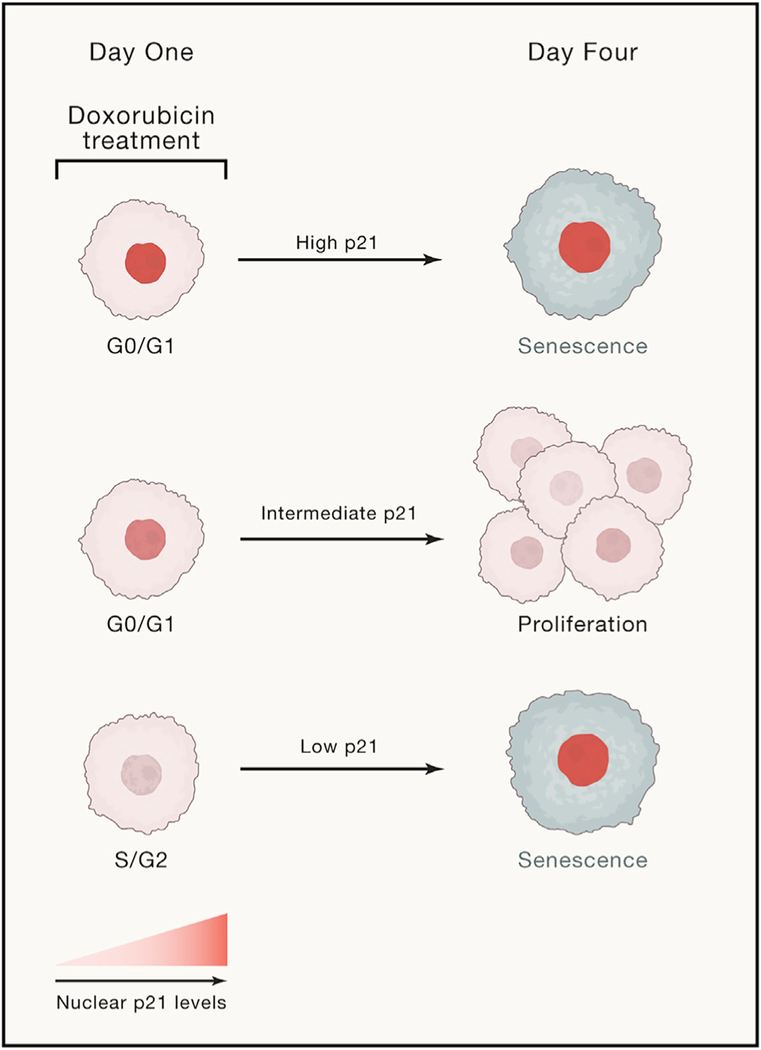

p21 is a p53 transcriptional target that is induced upon DNA damage and acts to arrest the cell cycle by inhibiting cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) (Abbas and Dutta, 2009). While elevated levels of p21 classically mark the senescent fate following chemotherapy, p21 upregulation also promotes proliferative outcomes by arresting the cell cycle in G0/G1 to avoid propagating or replicating damaged DNA (Arora et al., 2017; Moser et al., 2018). To reconcile these seemingly contrary roles of p21 in promoting both senescence and proliferation, Hsu et al. treated cancer cells for 24 h with the topoisomerase II inhibitor, doxorubicin. Topoisomerases are enzymes that manage the topological strain on DNA that arises during DNA replication. The authors utilized single-cell time-lapse imaging and cell tracking to follow cellular behavior during the 24 h treatment and for the subsequent 3 days after drug washout. Cells that underwent zero additional cell divisions after drug washout were assumed to never divide again and were designated senescent. The authors then analyzed the movies to find that the initial p21 dynamics during the 24 h drug treatment predict the senescent versus proliferative fate of individual cancer cells 4 days later (Figure 1). This time frame reveals how cells make the choice between proliferation and senescence before they commit to a single fate.

Figure 1. Senescence Bypass in Chemotherapy Is Due to Differences in Early p21 Dynamics.

Cells with high or low levels of p21 during doxorubicin treatment are fated to become senescent, while those with an intermediate amount of p21 undergo proliferation following drug washout. These cells evade rather than escape senescence.

Cells that were in S/G2 at the time of doxorubicin treatment had low levels of p21 (due to ongoing degradation of p21 by E3 ligases in S phase), accrued more DNA damage than G0/G1 cells, and adopted a senescent fate. By contrast, cells that were in G0/G1 during the treatment window rapidly upregulated p21, had lower levels of DNA damage, and later went on to divide, which correlated with a return to baseline p21 levels. Interestingly, a subset of these G0/G1 cells became senescent after accumulating exceptionally high levels of p21 that were sustained after drug washout. From this, the authors develop a simple “Goldilocks” model to explain how p21 levels predict and shape cell fate: cells with either low or very high levels of p21 are fated toward senescence, whereas cells with intermediate amounts of p21 are able to arrest temporarily in G0/G1 and later resume proliferation.

What causes some cells to ramp up p21 and arrest in G0/G1 in the presence of drug, while others enter S phase where they are more susceptible to drug-induced DNA damage? Using pharmacological perturbations, Hsu et al. suggest that heterogeneity in the proliferation-senescence decision may be partially explained by differences in the efficacy of the DNA damage checkpoint machinery at the G1/S boundary. To test this idea, the authors used an inhibitor of ATM (a kinase that is activated by DNA double-strand breaks) to bypass the DNA damage checkpoint in the presence of doxorubicin and observed a decrease 4 days later in the fraction of proliferating cells compared to doxorubicin alone. These data support a counterintuitive paradigm that promoting cancer cell proliferation in the presence of chemotherapy may enhance the effectiveness of these treatments. That is, by weakening the G1/S DNA damage checkpoint or otherwise forcing cancer cells out of G0/G1 in the presence of a chemotherapeutic, cells enter S phase and attempt DNA replication where they amass irreparable amounts of genotoxic stress and are pushed toward death or senescence.

The classic literature on the causes of tumor regrowth following chemotherapy treatment cites survival of cells that do not pass through S phase during the chemotherapy treatment (e.g., Skipper et al., 1970), but direct evidence for this was lacking until recently. Advances in single-cell time-lapse microscopy and long-term cell tracking are now enabling scientists to revisit these assumptions. Hsu et al. show that when p21 levels are high enough to arrest cells in G0/G1 but not so high as to cause senescence, cells are temporarily blocked from entering S phase, where they are most sensitive to the chemotherapy. This is consistent with the notion that G0/G1 represents a cell-cycle “safe space” for surviving chemotherapy (Arora and Spencer, 2017; Ryl et al., 2017) and that a p21-mediated arrest in G0/G1 enables future proliferation by protecting cells from therapy-induced damage.

While Hsu et al. provide a compelling model for senescence evasion in the context of chemotherapy, an open question is how the rules for escaping cell-cycle exit change for other types of treatments, such as targeted therapies. For example, will p21 dynamics sufficiently explain escape from cell-cycle arrest mediated by the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib or the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib, or could there be even more general factors governing the inception of senescence for different types of stress (Neurohr et al., 2019)?

With the advent of single-cell technologies, in particular time-lapse imaging, cell behavior at the time of drug treatment can be linked to eventual cell fate. Such strategies are now beginning to be used to study senescence (Hsu et al., 2019; Neurohr et al., 2019; Reyes et al., 2018; Ryl et al., 2017), but progress will be slow until the development of reliable single-cell markers to confidently identify senescent cells that will never divide again. For example, even the most widely used molecular marker of senescence, beta-galactosidase activity, appears under conditions in which some cells later go on to divide, raising concern over whether those cells were truly senescent in the first place (Sharpless and Sherr, 2015). Therefore, an important step toward stimulating senescence in the context of cancer therapies (or eliminating senescent cells in the context of aging) will be developing reliable single-cell markers to unequivocally identify senescent cells and to elucidate heterogeneity within the senescent state itself. More broadly, a better understanding of the variability and plasticity in the responses of individual cells to therapeutic drugs will enable the development of rational drug combinations to push cells more homogeneously toward desired outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Abbas T, and Dutta A (2009). p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 400–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora M, and Spencer SL (2017). A Cell-Cycle “Safe Space” for Surviving Chemotherapy. Cell Syst. 5, 161–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora M, Moser J, Phadke H, Basha AA, and Spencer SL (2017). Endogenous Replication Stress in Mother Cells Leads to Quiescence of Daughter Cells. Cell Rep. 19, 1351–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C-H, Altschuler SJ, and Wu LF (2019). Patterns of Early p21 Dynamics Determine Proliferation-Senescence Cell Fate after Chemotherapy. Cell 178, this issue, 361–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser J, Miller I, Carter D, and Spencer SL (2018). Control of the Restriction Point by Rb and p21. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E8219–E8227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neurohr GE, Terry RL, Lengefeld J, Bonney M, Brittingham GP, Moretto F, Miettinen TP, Vaites LP, Soares LM, Paulo JA, et al. (2019). Excessive Cell Growth Causes Cytoplasm Dilution and Contributes to Senescence. Cell 176, 1083–1097.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes J, Chen J-Y, Stewart-Ornstein J, Karhohs KW, Mock CS, and Lahav G (2018). Fluctuations in p53 Signaling Allow Escape from Cell-Cycle Arrest. Mol. Cell 71, 581–591.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryl T, Kuchen EE, Bell E, Shao C, Flórez AF, Mönke G, Gogolin S, Friedrich M, Lamprecht F, Westermann F, and Höfer T (2017). Cell-Cycle Position of Single MYC--Driven Cancer Cells Dictates Their Susceptibility to a Chemotherapeutic Drug. Cell Syst. 5, 237–250.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpless NE, and Sherr CJ (2015). Forging a signature of in vivo senescence. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 397–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skipper HE, Schabel FM Jr., Mellett LB, Montgomery JA, Wilkoff LJ, Lloyd HH, and Brockman RW (1970). Implications of biochemical, cytokinetic, pharmacologic, and toxicologic relationships in the design of optimal therapeutic schedules. Cancer Chemother. Rep. 54, 431–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]