Abstract

Aims This is an official guideline published and coordinated by the German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (DGGG) and the Austrian Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (OEGGG). Because of their rarity and heterogeneous histopathology, uterine sarcomas are challenging in terms of how they should be managed clinically, and treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach. To our knowledge, there are currently no binding evidence-based recommendations for the appropriate management of this heterogeneous group of tumors.

Methods This S2k guideline was first published in 2015. The update published here is the result of the consensus of a representative interdisciplinary group of experts who carried out a systematic search of the literature on uterine sarcomas in the context of the guidelines program of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG. Members of the participating professional societies achieved a formal consensus after a moderated structured consensus process.

Recommendations The consensus-based recommendations and statements include the epidemiology, classification, staging, symptoms, general diagnostic work-up and general pathology of uterine sarcomas as well as the genetic predisposition to develop uterine sarcomas. Also included are statements on the management of leiomyosarcomas, (low and high-grade) endometrial stromal sarcomas and undifferentiated uterine sarcomas and adenosarcomas. Finally, the guideline considers the follow-up and morcellation of uterine sarcomas and the information provided to patients.

Key words: uterine sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, endometrial stromal sarcoma, adenosarcoma, morcellation

I Guideline Information

Guidelines program of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG

For information on the guidelines program, please refer to the end of the guideline.

Citation format

Sarcoma of the Uterus. Guideline of the DGGG and OEGGG (S2k Level, AWMF Register Number 015/074, February 2019). Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2019; 79: 1043–1059

Guideline documents

The complete long version together with a slide version of this guideline and a list of the conflicts of interests of all authors involved are available in German on the homepage of the AWMF: http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/015-074.html

Guideline authors

Table 1 Lead author and/or coordinating lead author of the guideline.

| Author | AWMF professional society |

|---|---|

| Prof. Dominik Denschlag | German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe] |

Table 2 Participating authors.

| Author Mandate holder |

DGGG working group (AG)/AWMF/non-AWMF professional society/organization/association |

|---|---|

| * These persons have contributed substantially to the development of the guideline. They did not vote on Recommendations or Statements. Dr. M. Follmann (AWMF-certified guidelines advisor/moderator) was kind enough to moderate the guideline. Dr. P. Gaß (DGGG Guidelines Office, Erlangen) contributed substantially to the compilation of the long and short version of this guideline. | |

| Prof. Dr. E. Petru (Graz) | Österreichische Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (ÖGGG) |

| Prof. Dr. M. W. Beckmann (Erlangen) | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (DGGG) |

| PD Dr. S. Ackermann* (Darmstadt), Dr. H. G. Strauss (Halle/Saale), PD Dr. P. Harter (Essen), Prof. Dr. P. Mallmann (Köln), PD Dr. F. Thiel (Göppingen) | Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie (AGO) of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (DGGG)/Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft (DKG) |

| Prof. Dr. A. Mustea* (Greifswald) | Nordostdeutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologische Onkologie (NOGGO) |

| Prof. Dr. U. Ulrich (Berlin), PD Dr. I. Juhasz-Boess* (Homburg) | Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Endoskopie (AGE) |

| Prof. Dr. D. Schmidt* (Mannheim) | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Pathologie (DGP) |

| Prof. Dr. L. C. Horn (Leipzig) | Bundesverband Deutscher Pathologen (BDP) and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Pathologie (DGP) (substitute for Prof. Schmidt) |

| PD Dr. P. Reichardt (Berlin) | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hämato-Onkologie (DGHO) |

| Prof. Dr. D. Vordermark (Halle/Saale) | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Radioonkologie (DEGRO) and Arbeitsgemeinschaft Radioonkologie (ARO) (substitute for Prof. Lindel) |

| Prof. Dr. K. Lindel* (Karlsruhe) | Arbeitsgemeinschaft Radioonkologie (ARO) |

| Prof. Dr. T. Vogl (Frankfurt am Main) | Deutsche Röntgengesellschaft (DRG) and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Interventionelle Radiologie (DEGIR) (substitute for Prof. Kröncke) |

| Prof. Dr. T. Kröncke* (Augsburg) | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Interventionelle Radiologie (DEGIR) |

| Dr. W. Cremer (Hamburg) | Berufsverband der Frauenärzte (BVF) |

| Dr. K. Kast* (Dresden) | Arbeitsgemeinschaft Erbliche Tumore (AET) |

| Prof. Dr. G. Egerer (Heidelberg), Dr. R. Mayer-Steinacker (Ulm) | Arbeitsgemeinschaft Supportive Maßnahmen in der Onkologie (AGSMO) |

| Heidrun Haase (Bad Homburg) | Federal Womenʼs Self-help after Cancer Organization [Bundesverband Frauenselbsthilfe nach Krebs e. V.] |

| PD Dr. S. Hettmer* (Freiburg) | Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology [Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Onkologie und Hämatologie] |

| Prof. Dr. G. Köhler* (Greifswald) | Expert |

| Prof. Dr. C. Tempfer (Bochum) | Expert |

| Dr. M. Battista (Mainz) | Expert |

II Guideline Application

Purpose and objectives

The purpose of this guideline is to provide information and advice to women about the diagnostic work-up, treatment and follow-up of uterine sarcomas (with the exception of carcinosarcomas). The guideline focuses on the differentiated management of different subtypes. In addition, the guideline should provide a basis for decision-making about the appropriate treatment during interdisciplinary tumor conferences held in DKG-certified gynecological cancer centers and sarcoma centers currently being set up.

Targeted areas of patient care

inpatient care

outpatient care

Target user groups/target audience

This guideline is aimed at the following groups of people:

gynecologists in private practice

gynecologists working in hospitals

pathologists

radiation therapists

hemato-oncologists specializing in internal medicine

pediatric hemato-oncologists

radiologists

affected patients

Adoption and period of validity

The validity of this guideline was confirmed by the executive boards/heads of the participating professional societies/working groups/organizations/associations as well as by the board of the DGGG and of the DGGG Guideline Commission and the OEGGG in December 2018 and was thereby approved in its entirety. This guideline is valid from 1 December 2018 through to 30 November 2021. Because of the contents of this guideline, this period of validity is only an estimate.

III Methodology

Basic principles

The method used to prepare this guideline was determined by the class to which this guideline was assigned. The AWMF Guidance Manual (version 1.0) has set out the respective rules and requirements for different classes of guidelines. Guidelines are differentiated into lowest (S1), intermediate (S2) and highest (S3) class. The lowest class is defined as a set of recommendations for action compiled by a non-representative group of experts. In 2004, the S2 class was divided into two subclasses: a systematic evidence-based subclass (S2e) and a structural consensus-based subclass (S2k). The highest S3 class combines both approaches.

This guideline is classified as: S2k

Grading of evidence

Grading of evidence based on a systematic search, selection, evaluation and synthesis of the evidence base followed by a grading of the evidence is not envisaged for S2k-level guidelines. The respective individual Statements and Recommendations are only differentiated by syntax, not by symbols ( Table 3 ).

Table 3 Grading of recommendations.

| Level of recommendation | Syntax |

|---|---|

| Strong recommendation, highly binding | must/must not |

| Simple recommendation, moderately binding | should/should not |

| Open recommendation, not binding | may/may not |

Statements

Expositions or explanations of specific facts, circumstances or problems which do not include any direct recommendations for action included in this guideline are referred to as “Statements”. It is not possible to provide any information about the grading of evidence for these Statements.

Achieving consensus and strength of consensus

At structured NIH-type consensus-based conferences (S2k/S3 level) authorized participants attending the session vote on draft Statements and Recommendations. The process is as follows: a Recommendation is presented, its contents are discussed, proposed changes are put forward, and finally, all proposed changes are voted on. If a consensus has not been achieved (> 75% of votes), there is another round of discussions, followed by a repeat vote. Finally, the extent of consensus is determined based on the number of participants ( Table 4 ).

Table 4 Classification on the extent of agreement for consensus-based decisions.

| Symbol | Extent of agreement in percent | |

|---|---|---|

| +++ | Strong consensus | > 95% of participants agree |

| ++ | Consensus | > 75 – 95% of participants agree |

| + | Majority agreement | > 50 – 75% of participants agree |

| – | No consensus | < 51% of participants agree |

Expert consensus

As the name already implies, this refers to consensus decisions taken with regard to specific Recommendations/Statements without a prior systematic search of the literature (S2k) or for which evidence is lacking (S2e/S3). The term “expert consensus” (EC) used here is synonymous with terms used in other guidelines such as “good clinical practice” (GCP) or “clinical consensus point” (CCP). The strength of the recommendation is graded as previously described in the chapter “Grading of recommendations”, i.e., purely semantically (“must”/“must not” or “should”/“should not” or “may”/“may not”) and without the use of symbols.

IV Guideline

1 Introduction

1.1 Epidemiology, classification, staging

| Consensus-based Statement 1.S1 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Uterine sarcomas (homologous) are a heterogeneous group of rather rare malignancies (1.5 – 3/100 000) of the uterine musculature, endometrial stroma or uterine connective tissue. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 1.E2 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| References: 2 | |

| The postoperative staging of uterine sarcomas must be based on the most current pTNM classification. | |

The WHO classification lists the following entities as malignant mesenchymal tumors or malignant mixed epithelial-mesenchymal tumors 2 , 3 :

leiomyosarcoma (LMS),

low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (LG-ESS),

high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (HG-ESS),

undifferentiated uterine sarcoma (UUS),

adenosarcoma (AS),

PECome (perivascular epithelioid cell tumor), malignant variant.

The diagnosis of other extremely rare sarcomas of the uterus (e.g. rhabdomyosarcoma as an example of a heterologous sarcoma) must be based on the WHO classification of soft tissue sarcomas 4 .

This guideline considers the more common entities (LMS, LG-ESS, HG-ESS and UUS or AS) to the exclusion of extremely rare types (rhabdomyosarcoma in adulthood, angiosarcoma, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, liposarcoma, myxofibrosarcoma, alveolar soft part sarcoma and epithelioid sarcoma). A chapter on “Rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus in children and adolescents” was added to the guideline.

The mean patient age at onset of disease is between 50 and 70 years, depending on the tumor type. Identified risk factors include tamoxifen therapy. Moreover, the incidence of uterine sarcomas is 2 to 3 times higher for women of African descent compared to Asian women or women of European descent.

Carcinosarcomas, which used to be referred to as uterine sarcomas in earlier classifications (also known as malignant mixed Müllerian tumors), are no longer classified as uterine sarcomas but as uterine carcinomas 5 , 6 . For this reason, this tumor entity is now discussed in the German national S3 guideline “032-034OL Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-up of Patients with Endometrial Cancer” 7 (Staging – Tables 5 and 6 ).

Table 5 FIGO and TNM stages for leiomyosarcomas and endometrial stromal sarcomas* of the uterus.

| FIGO/TNM stage | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| * Tumors simultaneously present in the corpus uteri and the ovary/pelvis accompanied by ovarian/pelvic endometriosis must be classified as independent primary tumors. | ||

| I/T1 | Tumor limited to the uterus | |

| IA/T1a | Tumor 5 cm or less in greatest dimension | |

| IB/T1b | Tumor larger than 5 cm in greatest dimension | |

| II/T2 | Tumor extends beyond the uterus, within the pelvis | |

| IIA/T2a | Involvement of the adnexa (unilateral or bilateral) | |

| IIB/T2b | Tumor has spread to extrauterine pelvic tissue excluding the adnexa | |

| III/T3 | Tumor has infiltrated abdominal tissue | |

| N1 | IIIA/T3a | One site |

| IIIB/T3b | More than one site | |

| IIIC | Metastasis of pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes | |

| IV/T4 | IVA/T4 | Tumor has infiltrated bladder and/or rectum |

| IVB | Distant metastasis | |

Table 6 FIGO and TNM stages for adenosarcomas* of the uterus.

| FIGO/TNM stage | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| * Tumors simultaneously present in the corpus uteri and the ovary/pelvis accompanied by ovarian/pelvic endometriosis must be classified as independent primary tumors. | ||

| I/T1 | Tumor limited to the uterus | |

| IA/T1a | Tumor limited to the endometrium/endocervix without myometrial infiltration | |

| IB/T1b | Tumor has infiltrated less than half of the myometrium | |

| IC/T1c | Tumor has infiltrated ≥ 50% of the myometrium | |

| II/T2 | Tumor has spread to the pelvis | |

| IIA/T2a | Involvement of the adnexa (unilateral or bilateral) | |

| IIB/T2b | Tumor has spread to extrauterine pelvic tissue excluding the adnexa | |

| III/T3 | Intraabdominal tumor spread | |

| N1 | IIIA/T3a | One site |

| IIIB/T3b | More than one site | |

| IIIC | Metastasis of pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes | |

| IV/T4 | IVA/T4 | Tumor has infiltrated bladder and/or rectal mucosa |

| IVB | Distant metastasis | |

1.2 Symptoms, general diagnostic work-up (including imaging), general pathology

1.2.1 Symptoms

| Consensus-based Statement 1.S2 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Uterine sarcomas are not associated with any specific symptoms. | |

Generally suspicious symptoms include a “rapidly growing uterus” despite low estrogen levels in the postmenopausal period.

Although it has been suggested that rapid growth of the uterus (e.g., an increase in size resembling 6 weeks of pregnancy over a period of one year 8 ) may be an indication for sarcoma, an analysis by Parker and colleagues of more than 1300 patients (of whom around 350 had “rapid growth”) found no increased risk of sarcoma compared to the respective controls (0.27 vs. 0.23%) 9 .

Finally, it should be noted that there is no valid definition of what constitutes “rapid growth” nor has any useful data been published which would permit this parameter to be usefully evaluated in terms of being able to differentiate between myomas and sarcomas.

1.2.2 Imaging

| Consensus-based Recommendation 1.E3 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Because of the high potential for metastasis, histologically verified uterine sarcomas should be investigated further, including imaging (CT/MRI) of the thorax and abdomen. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 1.E4 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Imaging procedures or diagnostic interventions may not be able to exclude uterine sarcoma. | |

No imaging procedures (sonography, CT, MRT, PET-CT) have any specific or reliable criteria for detecting sarcomas 10 .

In general, transvaginal ultrasound is the most important primary diagnostic procedure used to evaluate the uterus.

Computed tomography may be used for abdominal imaging. This is particularly suitable for staging and to identify distant metastasis.

If a patient is known to have a sarcoma, the patient should also have a thoracic CT scan which can then serve as the basis for current management, with the findings used for follow-up.

1.2.3 General pathology

1.2.3.1 Specimens after hysterectomy or surgery of uterine sarcoma

| Consensus-based Recommendation 1.E5 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| References: 2 , 11 , 12 , 13 | |

The morphological work-up must find out all of the information listed below.

| |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 1.E6 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| As uterine sarcomas may be characterized by a high degree of intra-tumoral heterogeneity, all tumors with a maximum diameter of < 2 cm must be fully investigated. Tumors with diameters of > 2 cm must be embedded in paraffin, using one paraffin block per centimeter greatest tumor dimension. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 1.E7 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| If the findings do not provide clear information about the malignancy or subtype, a pathological examination must be carried out to investigate the tumor further. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 1.E8 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| All patients with a diagnosis of uterine sarcoma must be presented to an interdisciplinary tumor conference. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 1.E9 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus + |

| The presentation must be done at a DKG-certified gynecological cancer center or sarcoma center. | |

1.3 Genetic predisposition

| Consensus-based Recommendation 1.E10 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| If conditions for a germline analysis of the TP53 gen are present, patients must be offered genetic counseling with subsequent analysis to exclude LFS. | |

The majority of sarcomas occur sporadically. Nevertheless, a diagnosis of uterine sarcoma in childhood or early adulthood may be an indication of Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), an inherited familial predisposition to certain cancers.

2 Uterine leiomyosarcoma

2.1 Introduction, clinical and diagnostic work-up

In Northern Europe, sarcomas occur in about 0.4 cases/100 000 women across all age groups with the highest incidence found in women between the ages of 45 and 59 years 14 .

The median age at onset of disease is 50 years 15 .

Clinical symptoms reported by the patient can include abnormal bleeding (e.g. mid-cycle bleeding postmenopausal bleeding) and, depending on the size of the lesion, a sensation of pressure in the vagina or abdomen. However, in around 50% of cases (e.g., in women with postmenopausal bleeding), the results of curettage and/or endometrial biopsy can be false-negative and do not allow LMS to be clearly excluded 16 .

2.2 Histopathological diagnosis

The WHO classification lists both classic and spindle cell leiomyosarcoma as well as an epithelioid and a myxoid variant in its histological differentiation of sarcomas 2 .

The WHO classification does not grade uterine LMS 2 .

A diagnosis of smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP) 17 should only be made in exceptional cases if it is not possible to clearly differentiate between (classic) LMS and leiomyoma 18 , 19 , 20 .

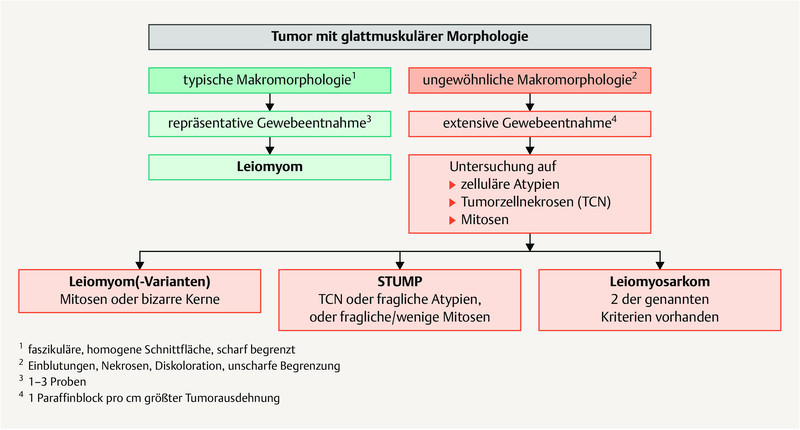

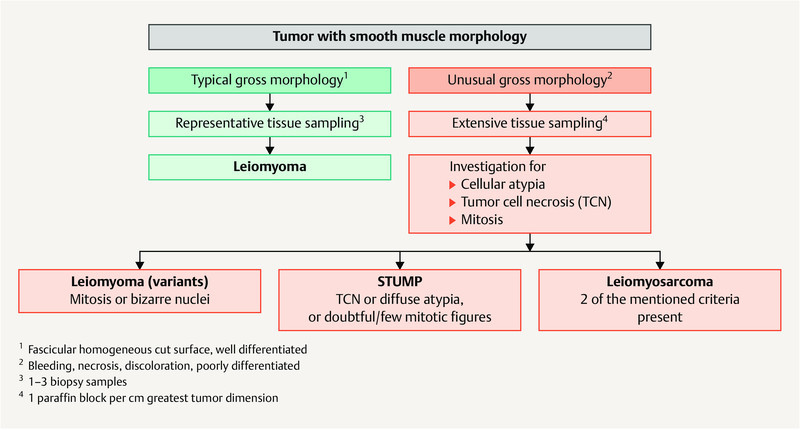

Fig. 1 shows a diagnostic algorithm for smooth muscle tumors 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 .

Fig. 1.

Diagnostic algorithm of smooth muscle tumors of the uterus. [rerif]

2.3 Prognosis

LMS are very aggressive tumors with an unfavorable prognosis. The rate of recurrence ranges from 53 to 71%, and the average 5-year overall survival rate is between 40 and 50% 24 , 25 .

Additional prognostic factors are age, tumor-free resection margins, mitotic index and vascular invasion 24 , 26 . The most important iatrogenic negative prognostic factors are morcellation or tumor injury, e.g. caused by a “myomectomy” 27 .

2.4 Surgical treatment

| Consensus-based Recommendation 2.E11 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Treatment of early-stage tumors must include complete removal of the uterus without morcellation but must include bilateral resection of the adnexa. In premenopausal patients, the ovaries may be preserved. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 2.E12 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy should not be carried out if the lymph nodes are diagnostically unremarkable. | |

Total hysterectomy is the gold standard for the surgical management of LMS which are limited to the uterus. The decision whether the adnexa need to be resected will usually depend on the patientʼs menopausal status. In young women, the ovaries can be preserved without affecting prognosis 26 , 28 , 29 . Ovarian metastasis is rare, with an incidence of just 3%, and occurs almost exclusively in cases with intraperitoneal spread 29 .

The incidence of primary pelvic and para-aortic lymph node metastasis is low in cases with LMS. If lymph node involvement is present (involvement is often already detected intraoperatively), then extrauterine or hematogenous metastasis is usually also present. This means that systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy is not associated with a better prognosis, and it is therefore generally not recommended 28 , 30 , 31 .

2.5 Adjuvant systemic therapy and radiotherapy

| Consensus-based Recommendation 2.E13 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy should not be generally administered. Depending on the presence of other risk factors (e.g. higher stage tumor) it may be administered in individual cases after carefully weighing up the potential drawbacks/benefits with the patient. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 2.E14 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Radiotherapy should not be carried out after complete resection of a stage I/II LMS. | |

Adjuvant systemic therapy is not generally indicated as no randomized controlled study has been able to provide evidence for any benefit in terms of overall survival 32 .

Based on the current results of both prospective phase II trials and a phase III trial, it appears that patients with leiomyosarcoma whose tumor is limited to the uterus (stage I – III A with involvement limited exclusively to the uterine serosa) could benefit from systemic therapy after surgery with no residual tumor.

In this context, it was found in a small phase III trial (n = 81 patients, 19 of whom presented with carcinosarcoma) that a combination of doxorubicin/ifosfamide/cisplatin had a significant positive effect on 3-year progression-free survival (55% had additional radiotherapy vs. 41% in the control group who had only radiotherapy), but it was accompanied by significantly higher toxicity 33 .

Another phase II trial (n = 47) which used combination chemotherapy with docetaxel and gemcitabine followed by doxorubicin had similarly good results in terms of PFS but with lower toxicity (3-year PFS: 57%) 34 , 35 .

Based on these results, it would appear that adjuvant chemotherapy should at least be discussed in certain individual cases, even if there is, as yet, no evidence that it leads to a significant improvement in overall survival.

A randomized study reported that adjuvant pelvic irradiation with 50.4 Gy in cases with stage I or II disease resulted in improved local control in a patient population with different sarcoma entities 36 , but in the subgroup of patients with leiomyosarcomas (n = 99) no effect was found on either the local rate of recurrence (20% with radiotherapy, 24% without radiotherapy) or the overall survival rate. This means that radiotherapy is not generally indicated after complete resection of a stage I/II LMS. Radiotherapy can be considered in patients with R1/2 resection and locally advanced disease if the tumor is limited to the pelvis.

2.6 Treatment for metastasis and recurrence

| Consensus-based Recommendation 2.E15 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| If the diagnosis is metastasized LMS, the first-line therapy must consist of doxorubicin. | |

There is some evidence to suggest that when treating patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma and recurrence or metastasis, complete surgical resection is associated with a better prognosis compared to chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 . Two studies carried out in a selected patient population reported improved survival rates (median survival: 45 vs. 31 months and 2.0 vs. 1.1 years, respectively) after complete resection of metastases in patients with leiomyosarcoma 37 , 41 .

Palliative systemic therapy is indicated for patients with diffuse metastasis and patients with recurrence/metastasis which cannot be/can no longer be treated with surgery. Such a therapy should be discussed in detail with the patient and the associated toxicity needs to be considered carefully.

There are only a few effective substances such as ifosfamide, gemcitabine or doxorubicin which can be used for mono-chemotherapy, and they are reported to have moderate rates of response (partial or complete remission) of between 17 and 25% 42 , 43 .

Paclitaxel, cisplatin, topotecan and etoposide are less effective and have low response rates of less than 10% 44 – 47 .

In contrast, although combination chemotherapies have higher response rates compared to monotherapies, the toxicity associated with combination therapies is higher 48 , 49 , 50 .

Only one prospective randomized phase II trial has shown that combination therapy is superior to mono-chemotherapy in terms of survival; therapy consisted of a combination of docetaxel/gemcitabine 51 . However, another study with a comparable design was unable to confirm the findings of the first study, so that it is still ultimately not clear whether this combination offers a benefit for patients 52 .

According to more recent data from a phase III trial, a combination of docetaxel and gemcitabine offered no benefits compared to monotherapy with doxorubicin to either the overall patient population with soft tissue sarcomas or the subgroup with uterine LMS (median overall survival: 67 vs. 76 weeks; HR: 1.14, 95% CI: 0.83 – 1.57; p = 0.41 for the total patient population, n = 257) 53 .

The use of trabectedin in second-line chemotherapy in a metastatic setting after prior administration of anthracyclines was investigated in phase II trials and should be the antitumoral drug of choice to treat this indication. Although the expected remission rates are very low, disease may be stabilized in up to 50% of cases 54 .

Pazopanib, a multiple tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is another second-line therapy option which has been investigated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial, although patients with a range of sarcoma types of varying histologies and with metastasis were included in the study. As regards the rate of remission and the percentage of patients who experienced disease stabilization, the same statement applies to pazopanib as for trabectedin. In this study, pazopanib significantly increased the progression-free survival period both in the overall patient population and in the subgroup of patients with leiomyosarcoma 55 .

3 Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas

3.1 Introduction, clinical and diagnostic work-up

The median age at onset of disease is the 6th decade of life 15 .

These tumors typically manifest as pathological bleeding, sometimes together with an enlarged uterus and corresponding symptoms.

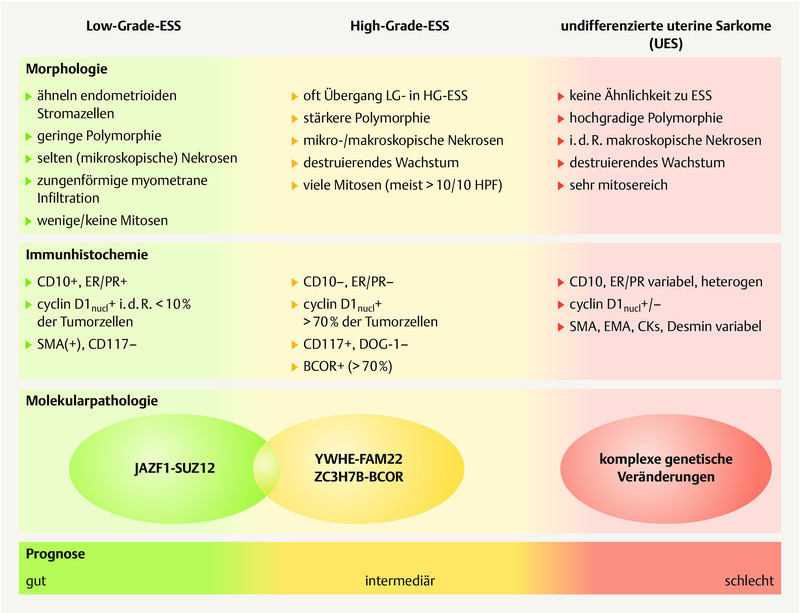

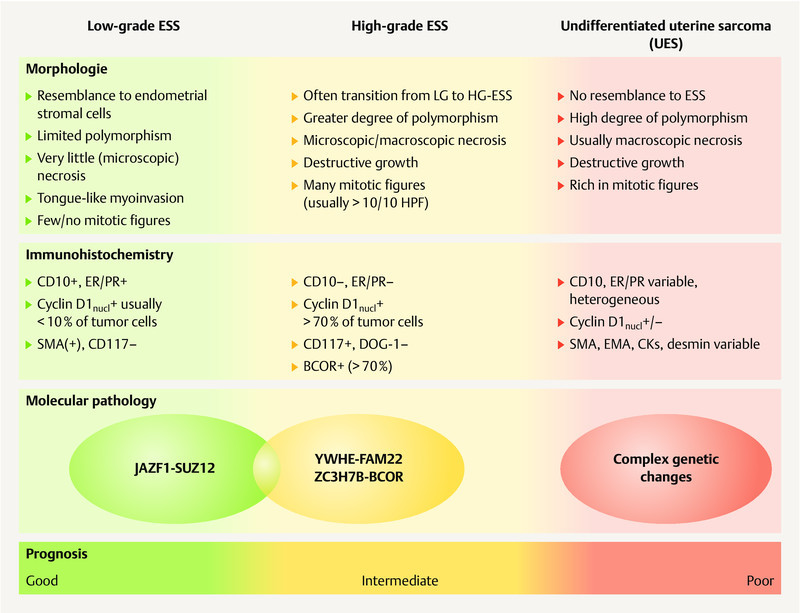

The WHO classification of malignant endometrial stromal tumors ( Fig. 2 ) differentiates between

Fig. 2.

Synopsis of the morphology, immunohistochemistry and molecular pathology of endometrial stromal sarcomas (ESS) and undifferentiated uterine sarcomas (UUS). [rerif]

low-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas,

high-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas and

undifferentiated uterine sarcomas 17 .

3.2 Prognosis

Tumor stage is the most important prognostic factor for low-grade ESS 56 . The disease-specific 5-year survival rate for low-grade ESS is 80 – 90% and the 10-year survival rate is approximately 70% 57 , 58 . If the tumor is limited to the uterus at the time of diagnosis (stage I), then the rates are even higher: 100 and 90%, respectively. The rate drops to 40% for higher stage disease 31 . Positive hormone receptors are a favorable prognostic factor with regard to overall survival 59 .

3.3 Surgical treatment

| Consensus-based Recommendation 3.E16 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Treatment of early-stage disease must consist of complete resection of the uterus without morcellation but with complete bilateral resection of the adnexa. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 3.E17 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Reference: 60 | |

| There are currently no data about the oncological safety of hormone replacement therapy after previous primary treatment of a low-grade ESS. Because the tumor biology of low-grade ESS is highly estrogen-dependent, patients should be dissuaded from starting hormone replacement therapy. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 3.E18 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy should not be carried out if the lymph nodes are diagnostically unremarkable. | |

The treatment of choice is total hysterectomy (without morcellation) and resection of both adnexa 61 .

There is a lot of evidence regarding the endocrine dependence of LG-ESS. A retrospective analysis of 153 patients with LG-ESS found a significantly increased rate of recurrence when the ovaries of premenopausal patients were not removed. Neither this analysis nor two other evaluations of the SEER database found that this had a negative impact on overall survival. Thus, the benefits of ovarian preservation in younger patients must be carefully weighed against the risk of a higher probability of recurrence and must be critically discussed with affected patients 62 , 63 , 64 .

Lymph node involvement does not appear to have an impact on prognosis. Systemic lymphadenectomy and any adjuvant therapy options based on systemic lymphadenectomy are therefore not expected to extend survival times, meaning that lymphadenectomy cannot be routinely recommended 10 , 58 , 64 , 65 .

3.4 Adjuvant systemic therapy and radiotherapy

| Consensus-based Recommendation 3.E19 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Adjuvant endocrine therapy should not be generally carried out, although it may be considered depending on the presence of other risk factors (e.g. higher tumor stage) in individual cases after carefully weighing up the drawbacks/benefits with the patient. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 3.E20 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy must not be carried out. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 3.E21 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy must not be carried out. | |

Postoperative adjuvant endocrine therapy may be discussed with patients with FIGO stage III disease and higher or after accidental morcellation, although prospective studies are lacking. The data from comparative retrospective analyses of adjuvant treatment support the use of either medroxyprogesterone acetate 200 mg/d (in Germany only available as 250 mg doses) or megestrol acetate 160 mg/d or as an alternative to aromatase inhibitors (letrozole 2.5 mg/d, anastrozole 1 mg/d or exemestane 25 mg/d). The appropriate duration for adjuvant treatment has not been sufficiently investigated. A period of 5 years is currently being discussed 66 , 67 , 68 .

There are no valid data available on adjuvant chemotherapy.

A large epidemiological study from the USA carried out in 3650 patients with uterine sarcoma showed that adjuvant pelvic irradiation (± brachytherapy) had a significant positive effect on loco-regional recurrence-free survival for both the total patient population 69 and the subgroup of patients with ESS (n = 361: after 5 years: 97 vs. 93%; after 8 years 97 vs. 87%). But another large epidemiological study from the USA in a total of 1010 patients with ESS was unable to confirm that adjuvant radiotherapy had a significant benefit on overall survival 58 . The only relevant randomized study on the use of pelvic radiation in patients with uterine sarcoma 36 included 30 patients with endometrial stromal sarcomas but did not carry out a separate survival analysis for this subgroup of patients. Because of the unclear data and the medium- and long-term side effects of adjuvant radiotherapy when loco-regional control is already good, this treatment is not generally indicated.

3.5 Treatment for metastasis and recurrence

| Consensus-based Recommendation 3.E22 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Tamoxifen is contraindicated for LG-ESS. | |

Endometrial stromal sarcomas usually have a better prognosis compared to leiomyosarcomas. However, recurrence is possible even after decades 70 . In every case with recurrence or metastasis, it is important to check whether surgery with the aim of complete macroscopic resection is possible 71 .

The targeted administration of percutaneous radiotherapy is a palliative option for local or loco-regional recurrence which cannot be completed resected 72 , 73 .

Systemic therapy can be administered in cases with postoperative residual tumor, inoperable recurrence with distant metastasis of low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. Because of the high expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors, progestogens or aromatase inhibitors are used to treat low-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 .

A retrospective analysis of a small case series found medroxyprogesterone acetate 200 mg/d (in Germany only available in doses of 250 mg) or megestrol acetate 160 mg/d to be effective. Response rates of up to 82% were reported 75 . Alternatively, although there is less data available, aromatase inhibitors (letrozole 2.5 mg/d, anastrozole 1 mg/d or exemestane 25 mg/d) also appear to have a positive effect 76 .

Because it is a risk factor for uterine sarcoma, tamoxifen must not be used for endocrine therapy 78 .

Any ongoing therapy with tamoxifen should be discontinued. If the use of tamoxifen is indicated because of breast cancer, treatment should be switched to an aromatase inhibitor.

4 High-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas and undifferentiated uterine sarcomas

4.1 Introduction, clinical and diagnostic work-up

Although there are distinct pathological anatomical differences between HG-ESS and UUS, both entities share a number of similarities in terms of their incidence, clinical presentation, prognosis and even therapy, which is why they are discussed together here. The staging corresponds to that for LMS.

The median age at onset of disease is 60 years. These tumors also typically manifest as pathological bleeding, sometimes together with an enlarged uterus and the corresponding symptoms.

As previously mentioned, the term “undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma (UES)” which was still included in the WHO classification of 2003 79 is no longer included in the most recent WHO classification 2 and should therefore no longer be used.

4.2 Prognosis

As regards prognosis, the prognosis for HG-ESS is between that of the more favorable prognosis associated with LG-ESS and the prognosis for aggressively progressive undifferentiated uterine sarcomas (UUS) 80 .

However, because disease is often only detected in its later stages, the prognosis is generally unfavorable with a median overall survival of just 1 – 2 years 81 , 82 .

4.3 Surgical treatment

| Consensus-based Recommendation 4.E23 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Treatment of early-stage disease must consist of complete resection of the uterus without morcellation but with complete bilateral resection of the adnexa. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 4.E24 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy should not be carried out if the lymph nodes are diagnostically unremarkable. | |

The treatment of choice also consists of complete hysterectomy (without morcellation) and bilateral adnexal resection. It is not clear whether the adnexa of premenopausal women can be left in situ.

Although positive pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes are associated with a poorer prognosis, there is currently no indication that surgical removal followed by consequent adjuvant therapy would lead to an improvement of this limited prognosis.

4.4 Adjuvant systemic therapy and radiotherapy

| Consensus-based Recommendation 4.E25 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy should not be routinely carried out, but it may be considered in individual cases depending on the presence of additional risk factors (e.g. higher tumor stage). | |

There are currently no valid data which indicate that postoperative endocrine therapy would benefit patients, even though evidence for hormone receptors is rare.

There are currently no valid data on the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy, which means that it must be discussed on an individual basis.

The data on adjuvant radiotherapy is similarly limited. A multicenter retrospective analysis evaluated 59 patients with endometrial stromal tumors, 29 of whom had undifferentiated uterine sarcoma (58% had stage I or II disease (FIGO 1988) 83 ). 86% of patients received pelvic teletherapy (median dose for the total patient population: 48 Gy) and 51% received brachytherapy. Overall survival after 5 years of patients with undifferentiated uterine sarcomas was 65% and 40% had loco-regional control. Multivariate analysis showed that in the total patient population (endometrial stromal sarcoma and undifferentiated uterine sarcoma) pelvic radiotherapy was associated with a significantly improved overall survival. However, because of the limited case numbers and the retrospective analysis it is not possible to draw definitive conclusions.

4.5 Treatment for metastasis and recurrence

There are some indications that certain recurrences are histologically heterogeneous (displaying aspects of both high- and low-grade tumors) and that in tumors with evidence of receptors, endocrine therapy only affects the low-grade part and not the high-grade part, although it is this high-grade component which ultimately determines prognosis 84 .

In contrast to LG-ESS, endocrine therapy does not play any role.

As regards the use of chemotherapy, this tumor entity can be treated similarly to other high-grade soft tissue sarcomas, although overall specific data on this point are limited.

5 Uterine adenosarcoma

5.1 Introduction, clinical and diagnostic work-up

This rare entity occurs in patients of all ages 85 but peaks in the 6th and 7th decades of life.

According to the WHO classification, adenosarcomas (AS) are defined as mixed epithelial-mesenchymal tumors of the uterus composed of benign epithelial and malignant mesenchymal components 86 , 87 .

If the mesenchymal component corresponds to a high-grade sarcoma (high-grade polymorphism, a higher mitotic rate, poss. myometrial or cervical stromal invasion and venous invasion with evidence of heterologous elements) and if this is detected in > 25% of the tumor, the diagnosis is an AS with sarcomatous overgrowth 88 .

5.2 Prognosis

The rate of recurrence for adenosarcoma without sarcomatous overgrowth is 15 – 25%, but this increases to 45 – 70% for patients with sarcomatous overgrowth. A higher rate of recurrence has also been reported for cases with deeper myometrial invasion, lymph node invasion, a highly malignant heterologous stromal component and/or extrauterine spread. The mortality rate for a typical adenosarcoma is 10 – 25%, but it can be as high as 75% for adenosarcoma with sarcomatous overgrowth.

5.3 Surgical treatment

As with other sarcomas, the treatment of choice is hysterectomy without morcellation. It is not clear whether the adnexa should also be removed.

The benefit of systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy is also not clear 66 . The probability of lymph node involvement is only 3 – 4% 89 . Because of this low incidence and the fact that in this analysis lymph node status has no impact on patient survival, systematic lymphadenectomy is not routinely recommended.

5.4 Adjuvant systemic therapy and radiotherapy

To date, no benefit has been reported for any adjuvant therapy. Based on 1884 cases in the National Cancer Database, chemotherapy has no effect on survival and postoperative radiotherapy even has a negative impact on survival 89 .

As with other uterine sarcomas, neither adjuvant systemic therapy nor radiotherapy are currently indicated after complete surgical resection.

If surgical resection was incomplete or in cases with advanced disease, the treating physician should consider whether sarcomatous overgrowth is present and/or whether hormone receptor expression is present; subsequent treatment should be similar to that for HG-ESS or LG-ESS.

5.5 Treatment for metastasis and recurrence

Because of the lack of data, the approach should be similar to that used for other uterine sarcomas, and surgery with complete resection is recommended.

Radiotherapy may be used as palliation to treat local inoperable recurrence or postoperatively to treat isolated findings.

There is no optimal regimen for systemic therapy. Recurrence of adenosarcoma with sarcomatous overgrowth should be treated the same way as other high-grade sarcomas 90 . Recurrence of adenosarcoma without sarcomatous overgrowth but with hormone receptor expression should be treated the same way as LG-ESS.

6 Follow-up

| Consensus-based Recommendation 7.E26 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| In the first 2 – 3 years after primary therapy, patients must be regularly followed up every three months with follow-up consisting of speculum examination, vaginal and rectal examination and, if necessary, ultrasound. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 7.E27 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| An additional diagnostic work-up for the early detection of metastasis may be beneficial. | |

Follow-up serves to ensure the success to treatment and safeguard the patientʼs quality of life.

It is, however, not clear whether intervention following the early detection of unilocular recurrence leads to an improvement in overall survival.

Nevertheless, the use of imaging as part of the further diagnostic work-up for the early detection of metastasis may be beneficial (cf. the specific chapters on individual entities).

7 Morcellation

| Consensus-based Recommendation 8.E28 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The use of morcellation techniques to remove uterine sarcomas results in a worse prognosis. Patients must be informed of this. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 8.E29 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Morcellation must not be carried out in a postmenopausal patient if the patient has been diagnosed with a newly developed “myoma”, a large rapidly growing “myoma” or a “myoma” which has become symptomatic for the first time. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 8.E30 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Contained in-bag morcellation cannot not exclude the possibility of tumor cell dissemination. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 8.E31 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Patients who had a morcellation procedure to remove a uterine sarcoma must present to a DKG-certified gynecological cancer center very soon after morcellation. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 8.E32 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Adjuvant systemic therapy should not be generally carried out; nevertheless, because of the higher risk of recurrence after morcellation, systemic therapy should be considered depending on the histological subtype. | |

Morcellation of what is assumed to be benign tissue can occur during uterus-preserving surgery for the management of fibroid myomas or during total and subtotal hysterectomy, although postoperative examination of the resected specimen may reclassify it as a uterine sarcoma. Morcellation of the uterus or of parts of the uterus such as myomas and body of the uterus can occur during both endoscopic and vaginal procedures.

The prevalence of undetected uterine sarcomas during hysterectomies and myomectomies as reported in the literature varies between 1/204 and 1/7400 (0.49 – 0.014%) 91 . A summary analysis of the rate of accidentally operated uterine sarcomas in 10 international studies with 8753 procedures resulted in an incidence of 0.24% 91 . A meta-analysis of 10 120 patients from 9 studies resulted in a comparable incidence of accidentally operated uterine sarcomas of 0.29% 92 . A German analysis carried out in 2017 of 475 morcellation procedures performed from 2004 to 2014 reported a risk of 0.35% (1/280) for the accidental morcellation of a previously unknown uterine sarcoma during hysterectomy and no case of uterine sarcoma detected during 195 myoma morcellations (0/195) 93 . Another German study of 10 731 LSH operations reported a rate of 0.06% uterine sarcomas and 0.07% endometrial carcinomas 94 .

Endoscopic intraabdominal morcellation of undetected sarcomas during hysterectomy, conservative surgical management of uterine myomas and laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LSH) have been particularly associated with worsening of the oncological prognosis in terms of recurrence-free survival and overall survival 91 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 .

In a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of 4 studies with 202 patients (75 with and 127 without morcellation) done in 2015, the rate of recurrence was higher after morcellation (62 vs. 39%; odds ratio [OR]: 3.16; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.38 – 7.26) as was the intraabdominal rate of recurrence (39 vs. 9%; OR: 4.11; 95% CI: 1.92 – 8.81). The overall survival rate after morcellation was also significantly lower (48 vs. 29%; OR: 2.42; 95% CI: 1.19 – 4.92) 101 . However, there was no difference in the extra-abdominal rate of recurrence. These data have been confirmed by other studies 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 but not by all 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 . All of the studies were retrospective observational studies.

There is very little data on the prognosis of patients who had accidental morcellation of a uterine malignancy during vaginal hysterectomy. Wasson et al. analyzed 2296 vaginal hysterectomies, with morcellation carried out in 611 cases 111 . The incidence of accidentally morcellated malignancies was 0.82% (5/611): 3 cases were endometrial carcinomas and 2 cases were sarcomas. There was no recurrence in 5/5 cases; mean disease-free survival was 48 months. Another analysis of more than 3000 hysterectomies which included a total of 18 sarcomas confirmed the observation that transvaginal morcellation does not increase the rate of recurrence 112 .

It is not possible to definitively exclude uterine sarcomas preoperatively based on clinical symptoms, growth patterns, ultrasound, CT, PET-CT or MR 91 , 113 .

Caution is always warranted if risk factors are present. In addition to age, the most common, known risk factor for uterine sarcoma is ongoing or completed tamoxifen therapy 114 . In addition, hereditary tumor syndromes such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome (which is associated with sarcoma) or Lynch syndrome and PTEN syndrome (which are associated with endometrial carcinoma) are also contra-indications for morcellation 115 .

The occurrence of sonographically visible or palpable uterine tumors in the postmenopausal period is unphysiological as is increased growth of a known “myoma”. Although none of these factors have been confirmed to be risk factors for uterine sarcoma, either in isolation or in combination, from a clinical and pathophysiological perspective it may be wise to assume that such cases may have an increased risk of uterine sarcoma.

The use of contained in-bag morcellation to prevent the dissemination of malignant cells has been described in various studies 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 . However, the technique of in-bag morcellation has not been clinically validated yet, and it is therefore not possible to make a reliable statement about the oncological safety of this technique 91 , 99 , 100 .

As regards the appropriate procedure after morcellation of a sarcoma, all further approaches should be guided by the statements made in the position paper of the German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics 91 and international recommendations and statements 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 . The statements also apply to open or endoscopic tumor resections with or without morcellation 108 . The consensus is that the appropriate oncologic surgery recommended for the individual tumor entity should be carried out as soon as possible. It has not been confirmed whether this approach affects overall survival.

8 Information for Patients

| Consensus-based Recommendation 9.E33 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Patients must be given the opportunity to include their partner or family members in talks and discussions. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 9.E34 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Patients should be informed about contacting self-help groups. | |

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The authorsʼ conflicts of interest are listed in the long version of the guideline./Die Interessenkonflikte der Autoren sind in der Langfassung der Leitlinie aufgelistet.

References/Literatur

- 1.Wittekind C, Meyer H J. Weinheim: Wiley-VHC Verlag; 2010. TNM-Klassifikation maligner Tumoren. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliva E, Carcangiu M L, Carinelli S G, Ip P, Loening T, Longacre T A, Nucci M R, Prat J, Zaloudek C J. Lyon: IARC Press; 2014. Mesenchymal Tumors of the Uterus; pp. 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conklin C M, Longacre T A. Endometrial stromal tumors: the new WHO classification. Adv Anat Pathol. 2014;21:383–393. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher C DM, Bridge J A, Hogendoorn P CW, Mertens F. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. WHO Classification of soft Tissue and Bone. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCluggage W G. Malignant biphasic uterine tumours: carcinosarcomas or metaplastic carcinomas? J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:321–325. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.5.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez-Garcia M A, Palacios J. Pathologic and molecular features of uterine carcinosarcomas. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2010;27:274–286. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF) Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge der Patientinnen mit Endometriumkarzinom, Langversion 1.0, 2018, AWMF Registernummer: 032/034-OLOnline:http://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/endometriumkarzinom/last access: 03.06.2019

- 8.Buttram V C, jr., Reiter R C. Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management. Fertil Steril. 1981;36:433–445. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)45789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker W H, Fu Y S, Berek J S. Uterine sarcoma in patients operated on for presumed leiomyoma and rapidly growing leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:414–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amant F, Coosemans A, Debiec-Rychter M. Clinical management of uterine sarcomas. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1188–1198. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70226-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coffey D, Kaplan A L, Ramzy I. Intraoperative consultation in gynecologic pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1544–1557. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-1544-ICIGP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otis C N, Ocampo A C, Nucci M R.Protocol for the Examination of Specimens From Patients With Sarcoma. 2013Online:http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/committees/cancer/cancer_protocols/2013/UterineSarcomaProtocol_3000.pdflast access: 27.08.2018

- 13.McCluggage W G, Fisher C, Hirschowitz L.Dataset for histological reporting of uterine sarcomas. 2014Online:http://www.rcpath.org/publications-media/publications/datasets/uterine-sarcomaslast access: 27.08.2018

- 14.Koivisto-Korander R, Martinsen J I, Weiderpass E. Incidence of uterine leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma in Nordic countries: results from NORDCAN and NOCCA databases. Maturitas. 2012;72:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaloudek C J, Hendrickson M R, Soslow R A. New York, Dodrecht, Heidelberg, London: Springer; 2011. Mesenchymal Tumors of the Uterus. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skorstad M, Kent A, Lieng M. Preoperative evaluation in women with uterine leiomyosarcoma. A nationwide cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95:1228–1234. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliva E. Cellular mesenchymal tumors of the uterus: a review emphasizing recent observations. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2014;33:374–384. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clement P B. The pathology of uterine smooth muscle tumors and mixed endometrial stromal-smooth muscle tumors: a selective review with emphasis on recent advances. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19:39–55. doi: 10.1097/00004347-200001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DʼAngelo E, Prat J. Uterine sarcomas: a review. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ip P P, Cheung A N. Pathology of uterine leiomyosarcomas and smooth muscle tumours of uncertain malignant potential. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25:691–704. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ly A, Mills A M, McKenney J K. Atypical leiomyomas of the uterus: a clinicopathologic study of 51 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:643–649. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182893f36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hart W R. Symposium 2: mesenchymal lesions of the uterus. Histopathology. 2002;41:12–31. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toledo G, Oliva E. Smooth muscle tumors of the uterus: a practical approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:595–605. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-595-SMTOTU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelmus M, Penault-Llorca F, Guillou L. Prognostic factors in early-stage leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:385–390. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a1bfbc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iasonos A, Keung E Z, Zivanovic O. External validation of a prognostic nomogram for overall survival in women with uterine leiomyosarcoma. Cancer. 2013;119:1816–1822. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garg G, Shah J P, Kumar S. Ovarian and uterine carcinosarcomas: a comparative analysis of prognostic variables and survival outcomes. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:888–894. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181dc8292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pritts E A, Parker W H, Brown J. Outcome of occult uterine leiomyosarcoma after surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.08.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kapp D S, Shin J Y, Chan J K. Prognostic factors and survival in 1396 patients with uterine leiomyosarcomas: emphasis on impact of lymphadenectomy and oophorectomy. Cancer. 2008;112:820–830. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nasioudis D, Chapman-Davis E, Frey M. Safety of ovarian preservation in premenopausal women with stage I uterine sarcoma. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017;28:e46. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2017.28.e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leitao M M, Sonoda Y, Brennan M F. Incidence of lymph node and ovarian metastases in leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:209–212. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seagle B L, Sobecki-Rausch J, Strohl A E. Prognosis and treatment of uterine leiomyosarcoma: A National Cancer Database study. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bogani G, Fuca G, Maltese G. Efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in early stage uterine leiomyosarcoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143:443–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.07.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pautier P, Floquet A, Gladieff L. A randomized clinical trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and cisplatin followed by radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in patients with localized uterine sarcomas (SARCGYN study). A study of the French Sarcoma Group. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1099–1104. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hensley M L, Ishill N, Soslow R. Adjuvant gemcitabine plus docetaxel for completely resected stages I–IV high grade uterine leiomyosarcoma: Results of a prospective study. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:563–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hensley M L, Wathen J K, Maki R G. Adjuvant therapy for high-grade, uterus-limited leiomyosarcoma: results of a phase 2 trial (SARC 005) Cancer. 2013;119:1555–1561. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gynaecological Cancer Group . Reed N S, Mangioni C, Malmström H. Phase III randomised study to evaluate the role of adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy in the treatment of uterine sarcomas stages I and II: an European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gynaecological Cancer Group Study (protocol 55874) Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:808–818. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernstein-Molho R, Grisaro D, Soyfer V. Metastatic uterine leiomyosarcomas: a single-institution experience. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:255–260. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181c9e289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leitao M M, Brennan M F, Hensley M. Surgical resection of pulmonary and extrapulmonary recurrences of uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;87:287–294. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levenback C, Rubin S C, McCormack P M. Resection of pulmonary metastases from uterine sarcomas. Gynecol Oncol. 1992;45:202–205. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90286-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiser M R, Downey R J, Leung D H.Repeat resection of pulmonary metastases in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma J Am Coll Surg 2000191184–190.discussion 190-191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giuntoli R L, 2nd, Garrett-Mayer E, Bristow R E. Secondary cytoreduction in the management of recurrent uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutton G P, Blessing J A, Barrett R J. Phase II trial of ifosfamide and mesna in leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:556–559. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91671-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) Study . Look K Y, Sandler A, Blessing J A. Phase II trial of gemcitabine as second-line chemotherapy of uterine leiomyosarcoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92:644–647. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thigpen T, Blessing J A, Yordan E. Phase II trial of etoposide in leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;63:120–122. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rose P G, Blessing J A, Soper J T. Prolonged oral etoposide in recurrent or advanced leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: a gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;70:267–271. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller D S, Blessing J A, Kilgore L C. Phase II trial of topotecan in patients with advanced, persistent, or recurrent uterine leiomyosarcomas: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Am J Clin Oncol. 2000;23:355–357. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200008000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gynecologic Oncology Group Study . Gallup D G, Blessing J A, Andersen W. Evaluation of paclitaxel in previously treated leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: a gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:48–51. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(02)00136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sutton G, Blessing J A, Malfetano J H. Ifosfamide and doxorubicin in the treatment of advanced leiomyosarcomas of the uterus: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;62:226–229. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hensley M L, Maki R, Venkatraman E. Gemcitabine and docetaxel in patients with unresectable leiomyosarcoma: results of a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2824–2831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarcoma Disease Site Group and the Gynecology Cancer Disease Site Group . Gupta A A, Yao X, Verma S. Systematic chemotherapy for inoperable, locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic uterine leiomyosarcoma: a systematic review. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2013;25:346–355. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maki R G, Wathen J K, Patel S R. Randomized phase II study of gemcitabine and docetaxel compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with metastatic soft tissue sarcomas: results of sarcoma alliance for research through collaboration study 002 [corrected] J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2755–2763. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pautier P, Floquet A, Penel N. Randomized multicenter and stratified phase II study of gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine and docetaxel in patients with metastatic or relapsed leiomyosarcomas: a Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer (FNCLCC) French Sarcoma Group Study (TAXOGEM study) Oncologist. 2012;17:1213–1220. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seddon B, Strauss S J, Whelan J. Gemcitabine and docetaxel versus doxorubicin as first-line treatment in previously untreated advanced unresectable or metastatic soft-tissue sarcomas (GeDDiS): a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1397–1410. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30622-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Demetri G D, Chawla S P, von Mehren M. Efficacy and safety of trabectedin in patients with advanced or metastatic liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma after failure of prior anthracyclines and ifosfamide: results of a randomized phase II study of two different schedules. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4188–4196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group; PALETTE study group . van der Graaf W T, Blay J Y, Chawla S P. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1879–1886. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60651-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chew I, Oliva E. Endometrial stromal sarcomas: a review of potential prognostic factors. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:113–121. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181cfb7c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang K L, Crabtree G S, Lim-Tan S K. Primary uterine endometrial stromal neoplasms. A clinicopathologic study of 117 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:415–438. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barney B, Tward J D, Skidmore T. Does radiotherapy or lymphadenectomy improve survival in endometrial stromal sarcoma? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1232–1238. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181b33c9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park J Y, Baek M H, Park Y. Investigation of hormone receptor expression and its prognostic value in endometrial stromal sarcoma. Virchows Arch. 2018;473:61–69. doi: 10.1007/s00428-018-2358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chu M C, Mor G, Lim C. Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: hormonal aspects. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:170–176. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Einstein M H, Barakat R R, Chi D S. Management of uterine malignancy found incidentally after supracervical hysterectomy or uterine morcellation for presumed benign disease. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:1065–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chan J K, Kawar N M, Shin J Y. Endometrial stromal sarcoma: a population-based analysis. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1210–1215. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bai H, Yang J, Cao D. Ovary and uterus-sparing procedures for low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: a retrospective study of 153 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shah J P, Bryant C S, Kumar S. Lymphadenectomy and ovarian preservation in low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1102–1108. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818aa89a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Si M, Jia L, Song K. Role of Lymphadenectomy for Uterine Sarcoma: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27:109–116. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gadducci A, Cosio S, Romanini A. The management of patients with uterine sarcoma: a debated clinical challenge. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:129–142. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamaguchi M, Erdenebaatar C, Saito F. Long-Term Outcome of Aromatase Inhibitor Therapy With Letrozole in Patients With Advanced Low-Grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:1645–1651. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amant F, De Knijf A, Van Calster B. Clinical study investigating the role of lymphadenectomy, surgical castration and adjuvant hormonal treatment in endometrial stromal sarcoma. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1194–1199. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sampath S, Schultheiss T E, Ryu J K. The role of adjuvant radiation in uterine sarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:728–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Piver M S, Rutledge F N, Copeland L. Uterine endolymphatic stromal myosis: a collaborative study. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nam J H. Surgical treatment of uterine sarcoma. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25:751–760. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weitmann H D, Knocke T H, Kucera H. Radiation therapy in the treatment of endometrial stromal sarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49:739–748. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01369-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kortmann B, Reimer T, Gerber B. Concurrent radiochemotherapy of locally recurrent or advanced sarcomas of the uterus. Strahlenther Onkol. 2006;182:318–324. doi: 10.1007/s00066-006-1491-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cheng X, Yang G, Schmeler K M. Recurrence patterns and prognosis of endometrial stromal sarcoma and the potential of tyrosine kinase-inhibiting therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:323–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.12.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dahhan T, Fons G, Buist M R. The efficacy of hormonal treatment for residual or recurrent low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. A retrospective study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;144:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maluf F C, Sabbatini P, Schwartz L. Endometrial stromal sarcoma: objective response to letrozole. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:384–388. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pink D, Lindner T, Mrozek A. Harm or benefit of hormonal treatment in metastatic low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: single center experience with 10 cases and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:464–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thanopoulou E, Aleksic A, Thway K. Hormonal treatments in metastatic endometrial stromal sarcomas: the 10-year experience of the sarcoma unit of Royal Marsden Hospital. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2015;5:8. doi: 10.1186/s13569-015-0024-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hendrickson M A, Tavassoli F A, Kempson R L, McCluggage W G, Haller U, Kubik-Huch R A.Mesenchymal Tumors and related Lesions IARC Press; 2003233–249.Online:https://www.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/BB4.pdflast access: 03.06.2019 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Benson C, Miah A B. Uterine sarcoma – current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:597–606. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S117754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Malouf G G, Lhomme C, Duvillard P. Prognostic factors and outcome of undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma treated by multimodal therapy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;122:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tanner E J, Garg K, Leitao M M., jr. High grade undifferentiated uterine sarcoma: surgery, treatment, and survival outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schick U, Bolukbasi Y, Thariat J. Outcome and prognostic factors in endometrial stromal tumors: a Rare Cancer Network study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:e757–e763. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Baniak N, Adams S, Lee C H. Extrapelvic Metastases in Endometrial Stromal Sarcomas: A Clinicopathological Review With Immunohistochemical and Molecular Characterization. doi:10.1177/1066896918794278. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27:208–215. doi: 10.1177/1066896918794278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fleming N A, Hopkins L, de Nanassy J. Mullerian adenosarcoma of the cervix in a 10-year-old girl: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22:e45–e51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McCluggage W G. Mullerian adenosarcoma of the female genital tract. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:122–129. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181cfe732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wells M, Oliva E, Palacios J, Prat J. Lyon: IARC Press; 2014. Mixed epithelial and mesenchymal Tumors of the Uterus; pp. 148–151. [Google Scholar]

- 88.McCluggage W G, Fisher C, Hirschowitz L.Dataset for histological reporting of uterine sarcomas. 2016Online:http://www.rcpath.org/publications-media/publications/datasets/uterine-sarcomaslast access: 27.08.2018

- 89.Seagle B L, Kanis M, Strohl A E. Survival of women with Mullerian adenosarcoma: A National Cancer Data Base study. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143:636–641. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tanner E J, Toussaint T, Leitao M M., jr. Management of uterine adenosarcomas with and without sarcomatous overgrowth. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Beckmann M W, Juhasz-Boss I, Denschlag D. Surgical Methods for the Treatment of Uterine Fibroids – Risk of Uterine Sarcoma and Problems of Morcellation: Position Paper of the DGGG. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2015;75:148–164. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1545684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brohl A S, Li L, Andikyan V. Age-stratified risk of unexpected uterine sarcoma following surgery for presumed benign leiomyoma. Oncologist. 2015;20:433–439. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kundu S, Zachen M, Hertel H. Sarcoma Risk in Uterine Surgery in a Tertiary University Hospital in Germany. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27:961–966. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bojahr B, De Wilde R L, Tchartchian G. Malignancy rate of 10,731 uteri morcellated during laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LASH) Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292:665–672. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3696-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Statement of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology to the Food and Drug Administrationʼs Obstetrics and Gynecology Medical Devices Advisory Committee Concerning Safety of Laparoscopic Power Morcellation. 2014Online:https://www.sgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/SGO-Testimony-to-FDA-on-Power-Morcellation-FINAL.pdflast access: 20.07.2018

- 96.Halaska M J, Haidopoulos D, Guyon F. European Society of Gynecological Oncology Statement on Fibroid and Uterine Morcellation. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27:189–192. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.AAGL Advancing Minimally Invasive Gynecology Worldwide. Morcellation During Uterine Tissue Extraction. 2014Online:https://www.aagl.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Tissue_Extraction_TFR.pdflast access: 20.07.2018

- 98.US Food and Drug Administration FDA Updated Assessment of The Use of Laparoscopic Power Morcellators to Treat Uterine Fibroids. 2017Online:https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/SurgeryandLifeSupport/UCM584539.pdflast access: 20.07.2018

- 99.Sizzi O, Manganaro L, Rossetti A. Assessing the risk of laparoscopic morcellation of occult uterine sarcomas during hysterectomy and myomectomy: Literature review and the ISGE recommendations. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;220:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.SOGC Clinical Practice-Gynaecology Committee; GOC Executive Committee . Singh S S, Scott S, Bougie O. Technical update on tissue morcellation during gynaecologic surgery: its uses, complications, and risks of unsuspected malignancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bogani G, Cliby W A, Aletti G D. Impact of morcellation on survival outcomes of patients with unexpected uterine leiomyosarcoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.George S, Barysauskas C, Serrano C. Retrospective cohort study evaluating the impact of intraperitoneal morcellation on outcomes of localized uterine leiomyosarcoma. Cancer. 2014;120:3154–3158. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Park J Y, Park S K, Kim D Y. The impact of tumor morcellation during surgery on the prognosis of patients with apparently early uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Raspagliesi F, Maltese G, Bogani G. Morcellation worsens survival outcomes in patients with undiagnosed uterine leiomyosarcomas: A retrospective MITO group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Raine-Bennett T, Tucker L Y, Zaritsky E. Occult Uterine Sarcoma and Leiomyosarcoma: Incidence of and Survival Associated With Morcellation. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:29–39. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lin K H, Torng P L, Tsai K H. Clinical outcome affected by tumor morcellation in unexpected early uterine leiomyosarcoma. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nemec W, Inwald E C, Buchholz S. Effects of morcellation on long-term outcomes in patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294:825–831. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lee J Y, Kim H S, Nam E J. Outcomes of uterine sarcoma found incidentally after uterus-preserving surgery for presumed benign disease. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:675. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2727-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gao Z, Li L, Meng Y. Correction: A Retrospective Analysis of the Impact of Myomectomy on Survival in Uterine Sarcoma. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0153996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gao Z, Li L, Meng Y. A Retrospective Analysis of the Impact of Myomectomy on Survival in Uterine Sarcoma. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wasson M, Magtibay P, 2nd, Magtibay P., 3rd Incidence of Occult Uterine Malignancy Following Vaginal Hysterectomy With Morcellation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]