Abstract

Background

Antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD) is a risk factor for exacerbating the outcome of critically ill patients. Dysbiosis induced by the exposure to antibiotics reveals the potential therapeutic role of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in these patients. Herein, we aimed to evaluate the safety and potential benefit of rescue FMT for AAD in critically ill patients.

Methods

A series of critically ill patients with AAD received rescue FMT from Chinese fmtBank, from September 2015 to February 2019. Adverse events (AEs) and rescue FMT success which focused on the improvement of abdominal symptoms and post-ICU survival rate during a minimum of 12 weeks follow-up were assessed.

Results

Twenty critically ill patients with AAD underwent rescue FMT, and 18 of them were included for analysis. The mean of Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores at intensive care unit (ICU) admission was 21.7 ± 8.3 (range 11–37). Thirteen patients received FMT through nasojejunal tube, four through gastroscopy, and one through enema. Patients were treated with four (4.2 ± 2.1, range 2–9) types of antibiotics before and during the onset of AAD. 38.9% (7/18) of patients had FMT-related AEs during follow-up, including increased diarrhea frequency, abdominal pain, increased serum amylase, and fever. Eight deaths unrelated to FMT occurred during follow-up. One hundred percent (2/2) of abdominal pain, 86.7% (13/15) of diarrhea, 69.2% (9/13) of abdominal distention, and 50% (1/2) of hematochezia were improved after FMT. 44.4% (8/18) of patients recovered from abdominal symptoms without recurrence and survived for a minimum of 12 weeks after being discharged from ICU.

Conclusion

In this case series studying the use of FMT in critically ill patients with AAD, good clinical outcomes without infectious complications were observed. These findings could potentially encourage researchers to set up new clinical trials that will provide more insight into the potential benefit and safety of the procedure in the ICU.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, Number NCT03895593. Registered 29 March 2019 (retrospectively registered).

Keywords: Fecal microbiota transplantation, Antibiotic-associated diarrhea, Intensive care unit, Critical care, Rescue therapy, Infections, Clostridium difficile, Multidrug resistance

Background

Antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD) is defined as otherwise unexplained diarrhea that occurs in association with disrupted gut microbiota caused by administration of antibiotics [1]. AAD occurs in about 5–35% of patients treated with antibiotics [1, 2] and more frequently in critically ill patients [3]. The large volume of watery stools and loss of electrolyte caused by AAD may aggravate the condition of a critically ill patient, leading to higher morbidity, longer hospitalization time, higher medical costs, and worse outcomes [3]. Besides, failure of conventional treatment for AAD is particularly frequent in critically ill patients due to their comorbidities, which has become a huge challenge for critically ill patients and their physicians. A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that probiotics were associated with a reduction of AAD, which indicated the potential preventive role of probiotics for AAD [4]. However, whether the effect can be found in critically ill patients remains uncertain.

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) accounts for about one third of AAD cases and for the vast majority of pseudomembranous colitis (PMC) cases [1]. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), which aims to restore the gut microbiota, has emerged as the most effective alternative for the management of recurrent CDI [5–9]. However, very few reports focus on the application of FMT to the treatment of AAD caused by other or unknown pathogens which accounts for about two thirds of AAD cases. Interestingly, recent reports showed that FMT appeared to be an option for multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) decolonization [10–12]. The safety of FMT had been ensured both in CDI and MDRO-colonized patients regardless of combination with immunosuppression or immunodeficiency [13, 14]. Our recent studies also reported the safety of FMT in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and some of them were immunocompromised [15, 16]. However, patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) were not included in these studies [15, 16]. Whether FMT can be a safe and effective treatment for AAD in critically ill patients requires further investigation. Given that the safety and value of FMT have been identified in severe and recurrent CDI and other gut microbiota dysbiosis-related diseases [9, 14, 17, 18], we aimed to investigate the safety and potential benefit of rescue FMT in critically ill patients with AAD.

Methods

This case series was performed in 16 ICUs of tertiary hospitals in China including 14 general ICUs and two pediatric ICUs. The rescue FMT therapy course was provided by Chinese fmtBank. This is a part of the registered study of long-term safety and efficacy of rescue FMT for refractory intestinal infections (ClinicalTrials.gov, Number NCT03895593).

Rescue FMT from Chinese fmtBank

The non-profit organization named Chinese fmtBank (fmtbank.org) provides rescue FMT service for patients with refractory intestinal infection across the whole nation. The protocol and workflow of fmtBank are shown in Additional file 2: Figure S1 and Additional file 3: Table S2. Due to the lack of CDI detection kits in most hospitals in China, the diagnosis of CDI could not be confirmed for all patients, and the reported incidence of refractory CDI in China is lower than that in reality [19–22]. Therefore, the indications of FMT from fmtBank in practice include recurrent or refractory CDI, refractory intestinal infections, and AAD. China Microbiota Transplantation System (CMTS) was set up simultaneously to evaluate long-term safety and efficacy of FMT.

Donor screening and management

All patients underwent FMT from unrelated universal donors who were 18–24 years old. Other than the initial eligibility screening, regular safety monitoring including dietary guidance, living environment follow-up, and laboratory examinations were scheduled for these donors. Protocol of donor screening and management has been described in our previous studies [16, 23] and is briefly shown in Additional file 3: Table S1.

Procedure of rescue FMT

Rescue FMT was performed by the cooperated team which consisted of at least two ICU physicians in charge from destination hospitals, two professional FMT clinicians (FZ and BC), two laboratory managers, and one clinical research coordinator from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. The procedure of rescue FMT is shown in Additional file 3: Table S2. Risk factors of serious adverse events (AEs) were evaluated by the rescue team as the exclusion criteria. Excluded patients included those with complete intestinal obstruction, suspected postoperative intestinal leak, and active intestinal fistula within 1 month; without optional FMT delivery way; unable to maintain a suitable position to avoid adverse events such gastric reflux and aspiration; without informed consent from the patient, patient’s family, or legal guardians; and those with other unsuitable conditions for rescue FMT. The rescue team members communicated closely throughout the whole process to ensure the safety of rescue FMT.

Patients and data collection

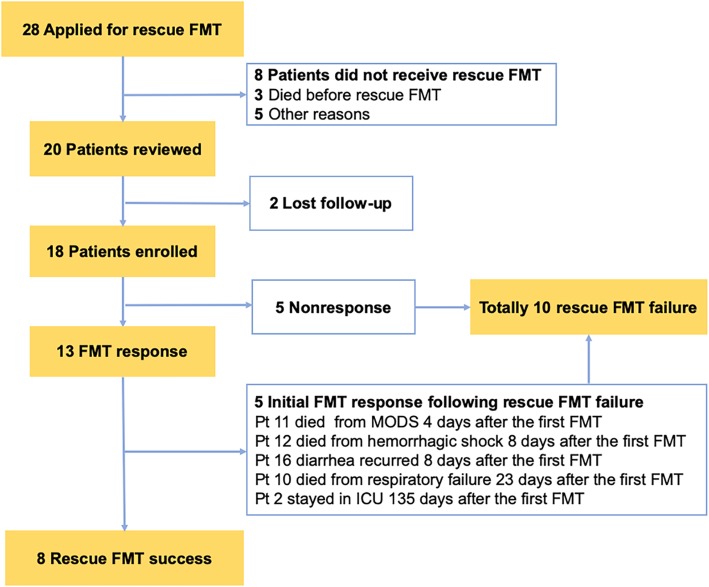

A database of 28 consecutive critically ill patients with AAD who applied for rescue FMT through their physicians from fmtBank, from September 2015 to February 2019, was reviewed (Fig. 1). Pre-FMT data of patients were collected through the medical records including the demographic characteristics, primary pre-FMT diagnosis from ICU, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, antibiotic use, probiotic use, abdominal symptoms, and laboratory findings. Part of post-FMT data was collected through the medical records when patients were in the study hospital. Patients were contacted via telephone and asked to finish a questionnaire (Additional file 1) that solicited post-FMT data when they were out of the hospital. A minimum of 12 weeks follow-up after rescue FMT was conducted.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart and reasons for rescue FMT failure

The outcomes and definitions

AEs and rescue FMT success during a minimum of 12 weeks follow-up were assessed. AEs referred to any new onset of symptoms, the exacerbation of previous symptoms, and abnormal laboratory findings with the use of FMT [24]. The occurrence of AEs in the ICU was recorded on a daily basis, while AEs that occurred out of the ICU were recorded via telephone follow-up or hospital visit. The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (Version 5.0) was applied to describe the intensity and relativity of AEs with FMT. The intensity of AEs was graded as mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2), severe (grade 3), life threatening (grade 4), and death (grade 5). Relationship between AEs and FMT was based on clinical judgment and all available information. Consideration of temporal association between FMT exposure and onset of the AEs, and whether the manifestations of the AEs were consistent with known actions or theoretical toxicity of FMT were included. Relationship between AEs and FMT was categorized as definitely related, probably related, possibly related, and unrelated according to a description from Kelly et al. about how to guide investigational new drug application for FMT [24]. AEs were reviewed and classified through voting by the rescue team members.

Rescue FMT success was defined as complete resolution of abdominal symptoms without recurrence and post-ICU survival for a minimum of 12 weeks. FMT response was featured to describe the improvement of abdominal symptoms within 1 week after rescue FMT. FMT nonresponse was defined as persistent abdominal symptoms after rescue FMT. Rescue FMT failure was defined as persistent or recurrent abdominal symptoms or continued ICU stay or death within 12 weeks after rescue FMT. FMT response and nonresponse were evaluated by at least two experienced ICU physicians in charge.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed in this case series. Patient characteristics were evaluated using mean ± standard deviations (SD) for normally distributed continuous variables, median and range for skewed continuous variables, and proportions for categorical variables. Data were analyzed by IBM SPSS 24.0 or GraphPad 7.0. Analyses included paired t test for normally distributed continuous paired data and Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test for skewed continuous paired data. Two tailed p value was calculated with each test. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of critically ill patients

A total of 20 critically ill patients underwent rescue FMT from fmtBank (Fig. 1). Patients who did not complete the follow-up were excluded from the analysis (n = 2). Eighteen patients (Table 1) (age median 55, range 2–91, two patients < 14, male/female 12/6) were included for analysis. The median time of the onset of primary abdominal symptoms before the rescue FMT was 31.5 days (range 8–120 days). The average APACHE II score at ICU admission was 21.7 ± 8.3 (range 11–37). Three patients were tested with Clostridium difficile toxin or culture, and one patient had a positive culture of Clostridium difficile and the other two were tested toxin negative.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics, clinical outcomes, and adverse events following FMT

| Pt | Age (year) | Sex | Primary ICU diagnosis at the time of rescue FMT | APACHE II score | Extra-intestinal infection sites | Microbiological culture (sample) | Rescue FMT (delivery way, frequency) | FMT response | Adverse events (AEs) | Antibiotic resuming time after FMT | 12 weeks survival | Rescue success | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-FMT | 3 days after FMT | 7 days after FMT | AEs (time after the first FMT) | Gradea | Causality between AEs and FMT | |||||||||||

| 1 | 25 | M | Cerebellar hemorrhage status post craniotomy, catheter associated bloodstream infection | 17 | 12 | Discharge | RT, blood | Klebsiella pneumoniae (blood) | Gastroscopy, one FMT | Diarrhea and abdominal distention improved | None | – | – | No use | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | 68 | M | Respiratory failure, pneumonia, post-CPR, cerebral infarction, postoperative prostate cancer, PD, GI bleeding | 28 | 26 | 24 | RT | Acinetobacter baumannii (sputum) | Nasojejunal tube, two FMTs | Abdominal distention and diarrhea improved | Hematuria (42 days) | – | Unrelated | 3 days | Yes | No |

| Sudden cardiac arrest (69 days) | – | Unrelated | ||||||||||||||

| Death (135 days) | – | Unrelated | ||||||||||||||

| 3 | 82 | F | Pulmonary infection, encephalatrophy | 11 | 11 | 11 | RT | Acinetobacter baumannii (sputum); Pseudomonas aeruginosa (sputum); negative (stool) | Nasojejunal tube, one FMT | Nonresponse | Death (52 days) | – | Unrelated | 13 days | No | No |

| 4 | 73 | M | Multiple trauma, pulmonary infection | 13 | Discharge | – | RT | Negative (blood) | Gastroscopy, one FMT | Diarrhea improved | Increased diarrhea frequency (< 1 day) | 2 | Probably related | 7 days | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | 17 | F | Septic shock, MODS, PMC, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, post-CPR | 24 | 19 | 14 | Blood, RT, skin, UT | Acinetobacter baumannii (sputum), E. coli (blood); Candida albicans (stool), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (urine) | Nasojejunal tube, four FMTs | Nonresponse after the first FMT, diarrhea and abdominal distention improved after the third FMT | Increased diarrhea frequency (< 1 day) | 2 | Probably related | 8 h | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | 54 | F | Rheumatic heart disease, post-valve replacement | 32 | 34 | 34 | RT, blood, UT | Candida Albicans (sputum, urine, stool), Klebsiella pneumoniae (sputum), Enterobacter cloacae (sputum, blood), E. coli (urine), Enterococcus aureus (urine) | Nasojejunal tube, two FMTs | Hematochezia alleviated, diarrhea and abdominal pain improved | Abdominal pain (< 1 day) | 1 | Probably related | 29 days | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | 3 | M | Sepsis, septic encephalopathy, MODS, PMC, post-ileostomy | 25 | 31 | 22 | Brain, blood, skin | Candida albicans (stool), Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hansen (stool) | Nasojejunal tube, one FMT | Diarrhea cured, abdominal distention improved | Increased diarrhea frequency (< 1 day) | 1 | Probably related | 7 days | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | 27 | F | Infective endocarditis, pulmonary infection, septic shock, thoracic empyema, PMC, MODS | 39 | 38 | 39 | Heart, RT, thoracic cavity | Candida glabrata (stool) | Nasojejunal tube, two FMTs | Nonresponse | Increased diarrhea frequency (3 days) b | 3 | Probably related | Continued antibiotic use | No | No |

| 9 | 27 | F | Sepsis, PMC, SLE (severe, active phase, systemic lupus erythematosus), lupus nephritis, pneumonia | 12 | 12 | 12 | Blood, RT | Enterococcus faecium (blood), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (sputum) | Nasojejunal tube, two FMTs | Transient diarrhea exacerbation, then abdominal distention and diarrhea improved | Hospitalization due to herpes zoster (116 days) | – | Unrelated | 24 h | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | 91 | M | Peri-anal abscess, CHD, COPD, cerebral infarction, arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, NYHA III, cholecystitis, gallstones | 20 | 18 | 18 | Anus, RT | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (sputum) | Nasojejunal tube, three FMTs | Diarrhea and abdominal distention improved | Death (23 days) | – | Unrelated | 14 days | No | No |

| 11 | 83 | M | COPDAE, respiratory failure, pulmonary encephalopathy, esophagus cancer, hypertension, DM | 35 | 23 | Died | RT | Acinetobacter baumannii (sputum) | Nasojejunal tube, one FMT | Diarrhea and abdominal distention improved | Death (4 days) | – | Unrelated | 20 h | No | No |

| 12 | 56 | M | Septic shock, brain stem infarction, MODS, upper GI bleeding, ischemic necrotizing enteritis? PMC? | 25 | 22 | Discharge | Blood, RT | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (blood, sputum) | Gastroscopy, one FMT | Diarrhea improved | Upper GI bleeding relapse (6 days) | – | Unrelated | 2 days | No | No |

| Death (8 days) | – | Unrelated | ||||||||||||||

| 13 | 35 | F | Multiple venous thrombosis, abdominal cavity infection, GI bleeding, abdominal hypertension syndrome, PMC, pulmonary infection | 22 | Died | – | Abdominal cavity, blood, RT | Acinetobacter baumannii (blood, sputum) | Enema, four FMTs | Nonresponse | Death (3 days) | – | Unrelated | No use | No | No |

| 14 | 41 | M | Sepsis, septic shock, MODS, post-SAP, pancreatic pseudocyst with acute infection, pulmonary infection, UTI | 12 | 11 | 7 | Pancreas, blood, RT, UT | Acinetobacter baumannii (abdominal cavity effusion), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (abdominal cavity effusion), Serratia marcescens (abdominal cavity effusion) | Nasojejunal tube, two FMTs | Nonresponse | Abdominal pain (< 1 day) | 1 | Possibly related | 24 h | No | No |

| Increased Serum amylase (< 1 day) | 1 | Possibly related | ||||||||||||||

| Death (46 days) | – | Unrelated | ||||||||||||||

| 15 | 59 | M | Multiple trauma, septic shock, PMC, hypertension, CHD | 27 | 17 | 15 | RT, blood, UT | Acinetobacter baumannii (sputum, blood, urine, stool) | Nasojejunal tube, two FMTs | Diarrhea and abdominal distention improved | None | – | – | 8 h | Yes | Yes |

| 16 | 2 | M | Cardiac arrest, respiratory failure, bronchitis, CNS infection, severe sepsis, severe malnutrition | 7 | 6 | 7 | RT, CNS | Negative (blood, sputum, urine, stool) | Gastroscopy, two FMTs | Diarrhea improved but relapsed 8 days after rescue FMT | Fever (< 1 day) | 1 | Possibly related | 24 h | Yes | No |

| 17 | 69 | F | Post-radical resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma, post-left hepatectomy | 7 | 7 | 7 | Stoma | Enterococcus aureus (stoma secretion) | Nasojejunal tube, one FMT | Nonresponse | None | – | – | 6 days | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | 56 | M | Septic shock, refractory CDI, multiple cerebral hemorrhage | 14 | 12 | Discharge | RT | Clostridium difficile (stool) | Nasojejunal tube, one FMT | Diarrhea, abdominal distention and abdominal pain improved | None | – | – | No use | Yes | Yes |

aThe grade of AEs was evaluated according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 5.0; b< 1 day post the second FMT. RT respiratory tract, PD Parkinson’s disease, CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation, GI gastrointestinal, MODS multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, PMC pseudomembranous enteritis, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, CHD coronary heart disease, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPDAE COPD acute exacerbation, DM diabetes mellitus, SAP severe acute pancreatitis, UTI urinary tract infection, CNS central nervous system

All patients had complicated extra-intestinal infections (Table 1), 66.7% (12/18) of them had more than one extra-intestinal infection site. The most common infection site was respiratory tract (RT), with 16 (88.9%) patients involved. Sixteen (88.9%) patients had a positive culture of MDRO. For the types of organisms, seven (43.8%) patients were infected with Acinetobacter baumannii, six (37.5%) with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and four (25.0%) with Enterococcus aureus. Eight (44.4%) patients had sepsis at the time of FMT, and five (27.8%) had multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS).

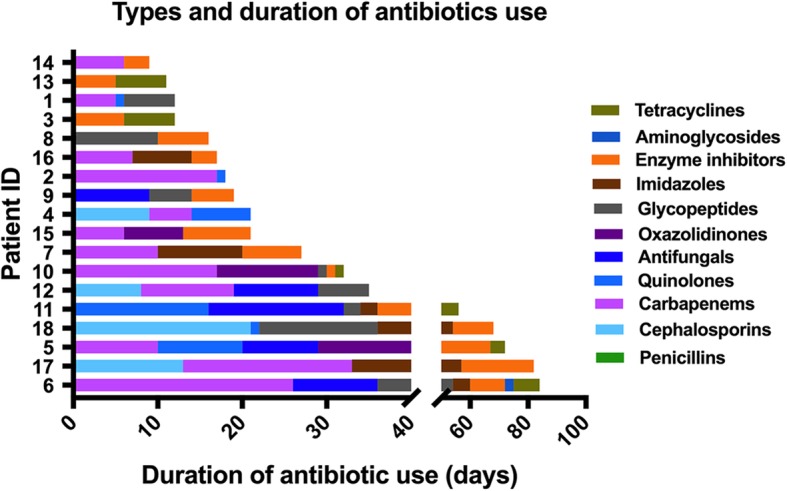

Antibiotic and probiotic use before and after FMT

Patients were treated with a mean of four (4.2 ± 2.1, range 2–9) types of antibiotic before and during the onset of AAD. The types and duration of antibiotic use are shown in Fig. 2. Six (33.3%) patients were medicated with vancomycin for the treatment of AAD before FMT, two (11.1%) with metronidazole, and two (11.1%) with vancomycin and metronidazole. Seventeen (94.4%) patients discontinued the antibiotic use 12–24 h before FMT. Besides, the majority of patients (83.3%) continued antibiotic treatment after FMT. Seven (38.9%) patients reused antibiotics within 24 h after FMT, 12 (66.7%) within one week after FMT. The antibiotic resuming time after FMT is listed in Table 1. Sixteen (88.9%) patients were given probiotics for the prevention or treatment for AAD before and during the AAD onset, and 13 (72.2%) patients took more than one type of probiotics.

Fig. 2.

Types and duration of antibiotic use before rescue FMT (n = 18)

Adverse events following rescue FMT

In total, 33 FMTs were performed on 18 critically ill patients (the frequency and delivery way of FMT are listed in Table 1). Among them, seven (7/18, 38.9%) patients had FMT-related AEs during follow-up. And Pt 14 had two FMT-related AEs. The most common FMT-related AEs were increased diarrhea frequency and abdominal pain. All AEs are listed in Table 1. Eight deaths occurred during the follow-up, which were categorized unrelated to FMT (Table 1). The core causes of death are listed in Additional file 3: Table S3. One patient (Pt 10) developed diarrhea exacerbation with increase of diarrhea frequency within 24 h after the first FMT due to the low temperature of fecal microbiota suspension. But the second FMT improved the diarrhea which was reflected on the improvement of stool consistency and decrease of diarrhea frequency. This patient recovered from severe sepsis and PMC and was finally discharged from ICU. She came back to the hospital for a checkup for pneumonia 8 weeks and 16 weeks after FMT. Chest computed tomography indicated the resolution of pneumonia. But she developed herpes zoster and was hospitalized 116 days after the first FMT, which was considered to be unrelated to FMT.

Clinical outcomes following rescue FMT

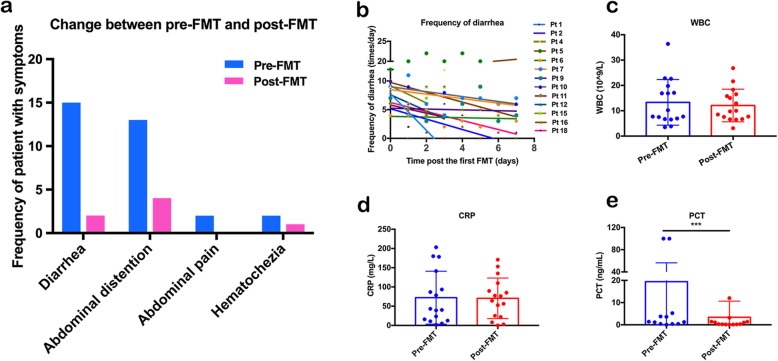

Clinical outcomes following rescue FMT for AAD in critically ill patients are shown in Table 1. 72.2% (13/18) of patients achieved FMT response within one week after FMT (Fig. 3a). Among 15 patients with primary abdominal symptoms of diarrhea, 86.7% (13/15) of them achieved improvement (Fig. 3b). 69.2% (9/13) of patients achieved improvement of abdominal distention including two patients as primary abdominal symptoms and seven as secondary abdominal symptoms. And 100% (2/2) of patients’ abdominal pain was improved, and 50% (1/2) of hematochezia was alleviated. In addition, the laboratory findings showed that WBC count, CRP, and PCT after FMT were decreased to a certain degree, though a significant difference can only be seen in PCT (p = 0.0005), compared with pre-FMT conditions (Fig. 3c–e).

Fig. 3.

Abdominal symptoms and laboratory markers of inflammation. a Frequency of patients with abdominal symptoms pre-FMT and post-FMT (n = 18). b Frequency of diarrhea of patients who were responsive to rescue FMT within 1 week post the first FMT (n = 13). c–e Level of WBC count, CRP, and PCT (p = 0.0005) pre-FMT and 1 week post the first FMT (n = 18)

Rescue FMT success was observed in eight (44.4%) patients, and the median length of follow-up was 50.6 weeks (range 12–191.8 weeks, by May 2019). Reasons for rescue FMT failure are shown in Fig. 1. Among the eight rescue success patients, five patients had bacteremia, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter cloacae, Enterococcus faecium, and Acinetobacter baumannii. Pt 1 was discharged from ICU 4 days after FMT and transferred to a recovery room without a re-examination of microbiological culture. Pt 5 was checked for the microbiological culture of blood 1 month after FMT, and the result indicated MDRO decolonization. The MDROs colonizing in Pt 7, 9, and 15 were not cleared before they were discharged from the ICU, and the final post-ICU results were not detected.

Discussion

This case series focused on the safety and potential benefit of rescue FMT for AAD in critically ill patients. The results showed that 38.9% (7/18) of patients had FMT-related AEs during the minimum of 12 weeks follow-up. No FMT-related death or infective complications occurred. 72.2% (13/18) of patients achieved improvement of abdominal symptoms within one week, and 44.4% (8/18) of patients acquired rescue FMT success.

The potential serious AEs such as infective complications following FMT in critically ill patients are the primary concern of clinicians, which have so far limited the use of FMT [25, 26]. There were a few case reports and case series about the application of FMT in critically ill patients in the ICU [27–31]. Less attention was paid particularly to the incidence of AEs of FMT in critically ill patients [28, 30]. In this series, 38.9% (7/18) of patients had FMT-related AEs, which was higher than that in previous studies of FMT for non-ICU patients [7, 15, 16, 18]. This may be attributed to that the patients in the ICU were more sensitive to the interventional changes. Importantly, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in June 2019 issued a serious FMT-related AE that may be attributed to the improper donor screening. This safety event highlighted the importance of strict criteria for donor screen [32, 33] and assessment on status of recipients including their age, immune fuction, and nutritional status [34]. In addition, the methodology of fecal microbiota preparation might be an important factor affecting safety [33, 34]. Our recent studies based on IBD patients indicated that purification of microbiota from donated stool in a GMP-level lab with an automatic machine contributed the significantly decreased AEs [15, 16, 33, 34].

For the heterogeneity of patients in the ICU, more data were needed to identify which subset of ICU patients would potentially benefit more from FMT with less AEs. Moreover, the procedure of rescue FMT for critically ill patients based on the multidisciplinary cooperation, individualized therapy strategy such as route of administration and antibiotic use, and management for AEs, was the most important part for ensuing safety of FMT. A multidisciplinary team has been set up in fmtBank including gastroenterologists who are professional in FMT, endoscopists, and infectious disease physicians as recommended by Cammarota et al. [26, 32]. The team cooperated with the patients’ physicians to perform FMT and monitor for the short-term (within one month post-FMT) and long-term (over one month post-FMT) AEs [16] to keep the safety of FMT as far as possible. The majority of FMT-related AEs in the present case series were mild to moderate and < 1 day after the first FMT except one severe AE in Pt 8. This patient’s condition progressed very quickly and developed severe diarrhea with blood and lots of necrotic intestinal mucosa mixed in the stool 17 days after the primary diarrhea onset. Her APACHE II score at the first 24 h of ICU admission was 39 (Additional file 4), which indicated the disease severity and high risk of mortality [35]. Multiple conventional therapies were used before rescue FMT but could not prevent the progression from AAD to PMC. Rescue FMT was used as the last attempt to save life in this patient but things did not work out.

Rescue FMT showed promising benefits for AAD in critically ill patients. 100% (2/2) of abdominal pain, 86.7% (13/15) of diarrhea, 69.2% (9/13) of abdominal distention, and 50% (1/2) of hematochezia can be alleviated by FMT. These results were similar to those of a recent case series which included nine critically ill patients with severe CDI [30]. It indicated that following FMT there was marked improvement in clinical status with resolution of diarrhea and reduction in abdominal distention and pain [30]. Alleviation of these abdominal symptoms may improve life quality of the critically ill patients and provided chances for other treatments. Interestingly, among the patients achieving rescue FMT success, five of them had bacteremia caused by enteric bacteria. One patient (Pt 5) had the clearance of bacteremia of E. coli after FMT with application of antibiotic treatment. Four patients were free of symptoms of bacteremia though there were no negative cultures of blood. Besides, Li et al. [36] described a 29-year-old woman with bacteremia of Acinetobacter baumannii whose microbiological culture of blood was negative 1 day after FMT without using antibiotics. Singh et al. [37] reported that three out of 15 (20%) patients carrying extended spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae were ESBL-negative at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after the first FMT, while six out of 15 (40%) were negative after the second transplant. But a recent randomized controlled study showed limited benefit of antibiotics followed by FMT for MDRO decolonization [12]. More prospective data are needed. And the timing for discontinuing and resuming antibiotics may be another important question. Continued antibiotic use during FMT and early resuming of antibiotics after FMT may be risk factors for multiple FMTs in this series.

Among the patients who achieved rescue FMT success, 62.5% (5/8) of them reused antibiotics within 1 week after the first FMT, but their diarrhea did not exacerbate or recur. Meanwhile, the complicated infections were alleviated. On the one hand, restoration of gut microbiota through FMT can repair the integrity of intestinal mucosal and prevent bacteria translation to acquire the improvement of diarrhea and reduction of inflammation [38]. On the other hand, gut microbiota has significant interactions on immunity [38]. Combination of conventional treatments and FMT may be more effective than either. Cui et al. described the concept of step-up FMT strategy which included step 1: single FMT; step 2: multiple FMTs; and step 3: FMT followed by steroids, which helped 57.1% of steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis patients maintain steroid dependence [17]. Fischer et al. suggested that additional antibiotic treatment for CDI after FMT, followed by a second FMT, may improve outcomes in patients with severe CDI [39], which is similar to the concept of step 3 in the step-up FMT strategy [17, 40].

Several studies showed the prevention and treatment value of probiotics for AAD [4, 41–43]. It is worth mentioning that 88.9% of patients in this case series were given probiotics to prevent or treat AAD. However, one single type or several types of probiotics seemed to have limited effects in critically ill patients with AAD. Compared with probiotics, FMT comes with risks of pathogen transmission from the donor and an increase of AEs but might be a better method for complete restoration of gut microbiota [38]. Nonetheless, further studies should aim at identifying the precise bacterial strains and specific functions, and two or more bacterial strains’ co-effect named selective microbiota transplantation (SMT) might be the new direction [33].

The limitation of this series is the small sample size of subjects and lack of control group. It is difficult to select critically ill patients for potential FMT trials because of the heterogeneity, so the bias cannot be avoided for the narrow subset of patients. In short of microbiota sequencing data, we are unable to provide direct evidence for dynamic changes of gut microbiota in critically ill patients before and after FMT. Further insights into the potential of precise bacterial strains and their specific functions as the predictive factors for FMT success and failure might be given by the integrated microbial analysis. The potential effect of FMT on MDRO decolonization also needs to be answered. Elaborately designed studies with a large sample size are needed.

Conclusion

In this case series studying the use of FMT in critically ill patients with AAD, good clinical outcomes without infectious complications were observed. These findings could potentially encourage researchers to set up new clinical trials that will provide more insight into the potential benefit and safety of the procedure in the ICU.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Rescue Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) Follow-Up Survey.

Additional file 2. Figure S1. Work flow of rescue FMT in Chinese fmtBank.

Additional file 3. Table S1. Protocol of donor screening, donor management and fecal microbiota preparation in Chinese fmtBank. Table S2. Procedure of rescue FMT for critically ill patients with AAD. Table S3. Time and Core causes of death during follow-up.

Additional file 4. Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score before and after FMT.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jie Zhang at China Microbiota Transplantation System (www.fmtBank.org) and Xiurui Lv for polishing the article. We also thank all participants for their information and cooperation with our follow-up.

Abbreviations

- AAD

Antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- CDI

Clostridium difficile infection

- PMC

Pseudomembranous colitis

- FMT

Fecal microbiota transplantation

- MDRO

Multidrug-resistant organisms

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- CMTS

China Microbiota Transplantation System

- AE

Adverse event

- APACHE

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- SD

Standard deviations

- RT

Respiratory tract

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- MODS

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- COPDAE

COPD acute exacerbation

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- UTI

Urinary tract infection

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CPR

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- WBC

White blood cell

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- PCT

Procalcitonin

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- ESBL

Extended spectrum beta lactamase

- SMT

Selective microbiota transplantation

Authors’ contributions

FZ and BC designed this study. MD analyzed the data and drew the manuscript. FZ, BC, and HB reviewed the manuscript. YL, WC, HB, YS, YB, CS, YH, DH, ZY, ZH, XH, JP, LH, XP, XW, BD, and ZL performed the rescue FMT and collected the medical data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by publicly donated Intestine Initiative Foundation; Primary Research & Development Plan of Jiangsu Province (BE2018751); Jiangsu Provincial Medical Innovation Team (FZ), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81600417), and China Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases (2015BAI13B07).

Availability of data and materials

The data used and analyzed in this case series are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case series was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from patients or pediatric patients’ parents or legal guardians.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Faming Zhang invented the concept of GenFMTer and related devices. Other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bota Cui, Phone: +86-025-58509884, Email: cuibota@njmu.edu.cn.

Faming Zhang, Phone: +86-025-58509883, Email: fzhang@njmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13054-019-2604-5.

References

- 1.Bartlett JG. Clinical practice. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(5):334–339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp011603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viswanathan VK, Mallozzi MJ, Vedantam G. Clostridium difficile infection: an overview of the disease and its pathogenesis, epidemiology and interventions. Gut Microbes. 2010;1(4):234–242. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.4.12706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zahar JR, Schwebel C, Adrie C, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Francais A, Vesin A, Nguile-Makao M, Tabah A, Laupland K, Le-Monnier A, et al. Outcome of ICU patients with Clostridium difficile infection. Crit Care. 2012;16(6):R215. doi: 10.1186/cc11852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hempel S, Newberry SJ, Maher AR, Wang Z, Miles JN, Shanman R, Johnsen B, Shekelle PG. Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;307(18):1959–1969. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullish BH, Quraishi MN, Segal JP, McCune VL, Baxter M, Marsden GL, Moore DJ, Colville A, Bhala N, Iqbal TH, et al. The use of faecal microbiota transplant as treatment for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection and other potential indications: joint British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and Healthcare Infection Society (HIS) guidelines. Gut. 2018;67(11):1920–1941. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee CH, Steiner T, Petrof EO, Smieja M, Roscoe D, Nematallah A, Weese JS, Collins S, Moayyedi P, Crowther M, et al. Frozen vs fresh fecal microbiota transplantation and clinical resolution of diarrhea in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(2):142–149. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kao D, Roach B, Silva M, Beck P, Rioux K, Kaplan GG, Chang HJ, Coward S, Goodman KJ, Xu H, et al. Effect of oral capsule- vs colonoscopy-delivered fecal microbiota transplantation on recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(20):1985–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.17077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cammarota G, Masucci L, Ianiro G, Bibbo S, Dinoi G, Costamagna G, Sanguinetti M, Gasbarrini A. Randomised clinical trial: faecal microbiota transplantation by colonoscopy vs. vancomycin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(9):835–843. doi: 10.1111/apt.13144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly CR, Khoruts A, Staley C, Sadowsky MJ, Abd M, Alani M, Bakow B, Curran P, McKenney J, Tisch A, et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on recurrence in multiply recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):609–616. doi: 10.7326/M16-0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinh A, Fessi H, Duran C, Batista R, Michelon H, Bouchand F, Lepeule R, Vittecoq D, Escaut L, Sobhani I, et al. Clearance of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae vs vancomycin-resistant enterococci carriage after faecal microbiota transplant: a prospective comparative study. J Hosp Infect. 2018;99(4):481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saha S., Tariq R., Tosh P.K., Pardi D.S., Khanna S. Faecal microbiota transplantation for eradicating carriage of multidrug-resistant organisms: a systematic review. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2019;25(8):958–963. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huttner BD, de Lastours V, Wassenberg M, Maharshak N, Mauris A, Galperine T, Zanichelli V, Kapel N, Bellanger A, Olearo F, et al. A 5-day course of oral antibiotics followed by faecal transplantation to eradicate carriage of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(7):830-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Kelly CR, Ihunnah C, Fischer M, Khoruts A, Surawicz C, Afzali A, Aroniadis O, Barto A, Borody T, Giovanelli A, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection in immunocompromised patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(7):1065–1071. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Battipaglia Giorgia, Malard Florent, Rubio Marie Therèse, Ruggeri Annalisa, Mamez Anne Claire, Brissot Eolia, Giannotti Federica, Dulery Remy, Joly Anne Christine, Baylatry Minh Tam, Kossmann Marie Jeanne, Tankovic Jacques, Beaugerie Laurent, Sokol Harry, Mohty Mohamad. Fecal microbiota transplantation before or after allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation in patients with hematologic malignancies carrying multidrug-resistance bacteria. Haematologica. 2019;104(8):1682–1688. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.198549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Cui B, Li Q, Ding X, Li P, Zhang T, Yang X, Ji G, Zhang F. The safety of fecal microbiota transplantation for Crohn’s disease: findings from a long-term study. Adv Ther. 2018;35(11):1935–1944. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0800-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding X, Li Q, Li P, Zhang T, Cui B, Ji G, Lu X, Zhang F. Long-term safety and efficacy of fecal microbiota transplant in active ulcerative colitis. Drug Saf. 2019;42(7):869–880. doi: 10.1007/s40264-019-00809-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui B, Li P, Xu L, Zhao Y, Wang H, Peng Z, Xu H, Xiang J, He Z, Zhang T, et al. Step-up fecal microbiota transplantation strategy: a pilot study for steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. J Transl Med. 2015;13:298. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0646-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costello SP, Hughes PA, Waters O, Bryant RV, Vincent AD, Blatchford P, Katsikeros R, Makanyanga J, Campaniello MA, Mavrangelos C, et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on 8-week remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(2):156–164. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.20046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Y, Mao L, Yu J, Lin Q, Luo Y, Zhu X, Sun Z. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized adults and the first isolation of C. difficile PCR ribotype 027 in Central China. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):232. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3841-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu H, Tang H, Xu T, Xiao M, Li J, Tan B, Yang H, Lv H, Li Y, Qian J. Retrospective analysis of Clostridium difficile infection in patients with ulcerative colitis in a tertiary hospital in China. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0920-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li C, Li Y, Huai Y, Liu S, Meng X, Duan J, Klena JD, Rainey JJ, Wu A, Rao CY. Incidence and outbreak of healthcare-onset healthcare-associated Clostridioides difficile infections among intensive care patients in a large teaching hospital in China. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:566. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao F, Li W, Gu W, Zhang W, Liu X, Fu X, Xu W, Wu Y, Lu J. A retrospective study of community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection in Southwest China. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):3992. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21762-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui B, Feng Q, Wang H, Wang M, Peng Z, Li P, Huang G, Liu Z, Wu P, Fan Z, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation through mid-gut for refractory Crohn’s disease: safety, feasibility, and efficacy trial results. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(1):51–58. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly CR, Kunde SS, Khoruts A. Guidance on preparing an investigational new drug application for fecal microbiota transplantation studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(2):283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klingensmith NJ, Coopersmith CM. Fecal microbiota transplantation for multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):398. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1567-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alagna L, Haak BW, Gori A. Fecal microbiota transplantation in the ICU: perspectives on future implementations. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(7):998–1001. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05645-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Q, Wang C, Tang C, He Q, Zhao X, Li N, Li J. Successful treatment of severe sepsis and diarrhea after vagotomy utilizing fecal microbiota transplantation: a case report. Crit Care. 2015;19:37. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0738-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz-Stubner S, Textor Z, Anetseder M. Fecal microbiota therapy as rescue therapy for life-threatening Clostridium difficile infection in the critically ill: a small case series. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(9):1129–1131. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei Y, Yang J, Wang J, Yang Y, Huang J, Gong H, Cui H, Chen D. Successful treatment with fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and diarrhea following severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):332. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1491-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alukal Joseph, Dutta Sudhir K, Surapaneni Balarama Krishna, Le Michelle, Tabbaa Obada, Phillips Laila, Mattar Mark C. Safety and efficacy of fecal microbiota transplant in 9 critically ill patients with severe and complicated Clostridium difficile infection with impending colectomy. Journal of Digestive Diseases. 2019;20(6):301–307. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wurm P, Spindelboeck W, Krause R, Plank J, Fuchs G, Bashir M, Petritsch W, Halwachs B, Langner C, Hogenauer C, et al. Antibiotic-associated apoptotic enterocolitis in the absence of a defined pathogen: the role of intestinal microbiota depletion. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(6):e600–e606. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cammarota G, Ianiro G, Tilg H, Rajilic-Stojanovic M, Kump P, Satokari R, Sokol H, Arkkila P, Pintus C, Hart A, et al. European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut. 2017;66(4):569–580. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang F, Cui B, He X, Nie Y, Wu K, Fan D, Group FM-sS Microbiota transplantation: concept, methodology and strategy for its modernization. Protein Cell. 2018;9(5):462–473. doi: 10.1007/s13238-018-0541-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang F, Zhang T, Zhu H, Borody TJ. Evolution of fecal microbiota transplantation in methodology and ethical issues. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2019;49:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marsh HM, Krishan I, Naessens JM, Strickland RA, Gracey DR, Campion ME, Nobrega FT, Southorn PA, McMichan JC, Kelly MP. Assessment of prediction of mortality by using the APACHE II scoring system in intensive-care units. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65(12):1549–1557. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(12)62188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Q, Wang C, Tang C, He Q, Zhao X, Li N, Li J. Therapeutic modulation and reestablishment of the intestinal microbiota with fecal microbiota transplantation resolves sepsis and diarrhea in a patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(11):1832–1834. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh R, de Groot PF, Geerlings SE, Hodiamont CJ, Belzer C, Berge I, de Vos WM, Bemelman FJ, Nieuwdorp M. Fecal microbiota transplantation against intestinal colonization by extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae: a proof of principle study. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):190. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3293-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Limketkai BN, Hendler S, Ting PS, Parian AM. Fecal microbiota transplantation for the critically ill patient. Nutr Clin Pract. 2019;34(1):73–79. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fischer M, Sipe BW, Rogers NA, Cook GK, Robb BW, Vuppalanchi R, Rex DK. Faecal microbiota transplantation plus selected use of vancomycin for severe-complicated Clostridium difficile infection: description of a protocol with high success rate. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42(4):470–476. doi: 10.1111/apt.13290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cui B, Li P, Xu L, Peng Z, Xiang J, He Z, Zhang T, Ji G, Nie Y, Wu K, et al. Step-up fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) strategy. Gut Microbes. 2016;7(4):323–328. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2016.1151608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alberda Cathy, Marcushamer Sam, Hewer Tayne, Journault Nicole, Kutsogiannis Demetrios. Feasibility of a Lactobacillus casei Drink in the Intensive Care Unit for Prevention of Antibiotic Associated Diarrhea and Clostridium difficile. Nutrients. 2018;10(5):539. doi: 10.3390/nu10050539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jafarnejad S, Shab-Bidar S, Speakman JR, Parastui K, Daneshi-Maskooni M, Djafarian K. Probiotics reduce the risk of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in adults (18-64 years) but not the elderly (>65 years): a meta-analysis. Nutr Clin Pract. 2016;31(4):502–513. doi: 10.1177/0884533616639399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pozzoni P, Riva A, Bellatorre AG, Amigoni M, Redaelli E, Ronchetti A, Stefani M, Tironi R, Molteni EE, Conte D, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in adult hospitalized patients: a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(6):922–931. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Rescue Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) Follow-Up Survey.

Additional file 2. Figure S1. Work flow of rescue FMT in Chinese fmtBank.

Additional file 3. Table S1. Protocol of donor screening, donor management and fecal microbiota preparation in Chinese fmtBank. Table S2. Procedure of rescue FMT for critically ill patients with AAD. Table S3. Time and Core causes of death during follow-up.

Additional file 4. Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score before and after FMT.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and analyzed in this case series are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.