Abstract

Background

Emerging evidence shows that microRNA-130 (miRNA-130) family may be useful as prognostic biomarkers in cancer. However, there is no confirmation in an independent validation study. The aim of this study was to summarize the prognostic value of miRNA-130 family (miRNA-130a and miRNA-130b) for survival in patients with cancer.

Methods

The pooled hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the association strength between miRNA-130 family expression and prognosis. Kaplan–Meier plotters were used to verify the miRNA-130b expression and overall survival (OS).

Results

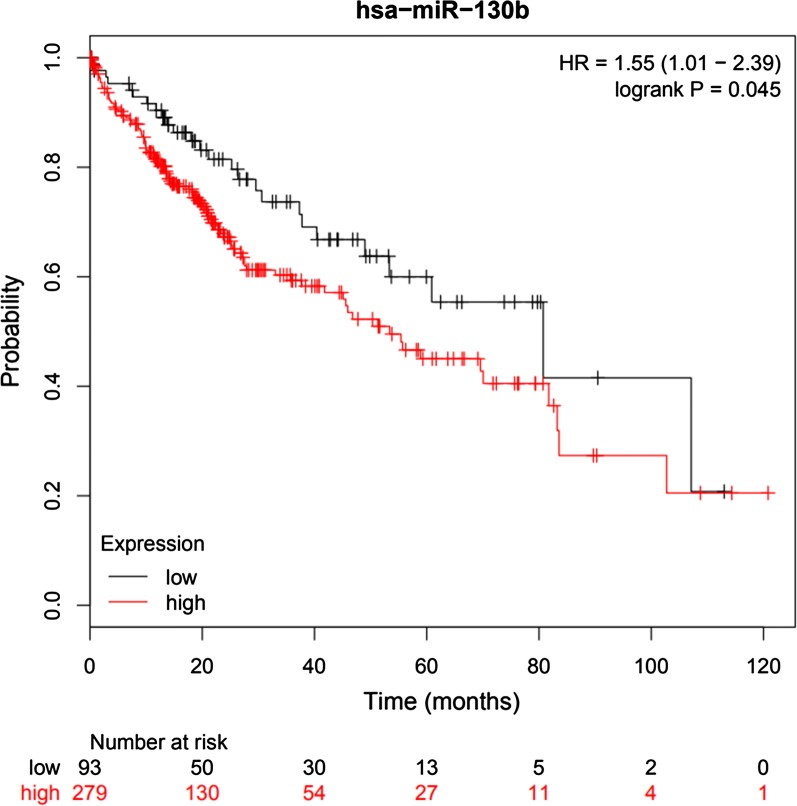

A total of 2141 patients with OS and 1159 patients with disease-free survival (DFS)/progression-free survival (PFS) were analyzed in evidence synthesis. For the miRNA-130a, the overall pooled effect size (HR) was HR 1.58 (95% CI: 1.21–2.06, P < 0.001). Tissue and serum expression of miRNA-130a was significantly associated with the OS (HR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.11–2.14, P = 0.009; HR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.14–2.38, P = 0.008), and in gastric cancer (HR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.34–2.45, P < 0.001). For the miRNA-13b, a statistical correlation was observed between high miRNA-130b expression and poor OS in patients with cancer (HR = 1.95, 95% CI: 1.47–2.59, P < 0.001), especially in tissue sample (HR = 2.01, 95% CI: 1.39–2.91, P < 0.001), Asian (HR = 2.55, 95% Cl: 1.77–3.69, P < 0.001) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HR = 1.87, 95% CI: 1.23–2.85, P = 0.004). The expression of miRNA-130b was significantly correlated with DFS/PFS (HR = 1.53, 95% CI: 1.31–1.77, P < 0.001), in tissue (HR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.50–2.62, P < 0.001) and serum (HR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.15–1.64, P < 0.001), especially in HCC (HR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.50, 2.62, P < 0.001). In database test, a significant correlation between high miRNA-130b expression and poor OS for HCC patients was observed (HR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.01, 2.35, P = 0.0045).

Conclusion

The high expression of miRNA-130 family might predict poor prognosis in cancer patients. Prospectively, combining miRNA-130a and miRNA-130b may be considered as powerful prognostic predictor for clinical application.

Keywords: miRNA-130a, miRNA-130b, Cancer, Prognosis, Systematic evaluation

Background

Cancer is recognized as the leading cause of human death [1], and the most important single barrier to improve life expectancy globally, in spite of advances in diagnosis and therapy [2]. Although cumulative tumor markers and pathological parameters have been discovered [3], only a few biomarkers can be used clinically because of tumor heterogeneity and biomarker extensibility [4]. And more effective and reliable biomarkers for cancer prognosis still need to be identified.

MicroRNA (miRNA) is a small (21 to 23 nucleotide), highly conserved, non-coding RNA that regulates gene expression by base pairing with the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of the mRNA [5]. Numerous studies have shown that miRNAs play crucial roles in biological behavior of various tumors, including proliferation, metastasis and invasion [6, 7]. Therefore, as non-invasive biomarkers, miRNAs may imply significant predictive value for tumor prognosis [8].

The miRNA-130 family, including miRNA-130a and miRNA-130b, is entangled intricately in tumor via an ambiguous way [9]. Studies have showed that miRNA-130a facilitated proliferation, invasion and metastasis of tumor cells [10–13], which may be associated with treatment resistance [14] and poor disease-free survival (DFS) [15] and overall survival (OS) [16, 17]. The potential mechanisms may involved down-regulation of tumor suppressor gene, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) in osteosarcoma and breast cancer [11, 12], runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX-3) and collapsing-response mediator protein type 4 (CRMP4) in gastric cancer [10, 17], peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG) in chorangiocarcinoma [16] and enhanced mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway in ovarian cancer [13]. However, a retrospective analysis showed that miRNA-130a had no significant effect on the prognosis of gastric cancer [18]. Moreover, miRNA-130a, acted like a tumor suppressor, has been reported to inhibit the androgen receptor (AR) and mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways and target FOS-like antigen 1 (FOSL1) in prostate cancer [19], and triple-negative breast cancer [20], respectively. And an analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) survival data suggested that high expression of miRNA-130a was significantly associated with long OS [21].

Studies have shown that epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) could be induced by miRNA-130b in gliomas colorectal cancer and HCC via debilitation of PPARG [22] or PTEN [23] assisting malignant proliferation, metastasis and invasion, which may be associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis [24–26]. This characteristic that contributes to tumorigenesis and progression has also been discovered in gastric cancer, which may be achieved by mediation of RUNX3 [27] and Ras-related protein activator like 1 (RASAL1) [28]. Nevertheless, according to their research, some scholars argued that miRNA-130b was not associated with tumor progression and OS/DFS in gliomas [29] and colorectal cancer [30]. Oppositely, miRNA-130b may attenuate the proliferation and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells by inhibiting the expression of signal transductor and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) [31].

Based on the above controversial results, the prognostic significance of miRNA-130 family in tumors remains equivocal. Currently, there is insufficient support on evidence-based medicine for prognostic significance of miR-130 family in cancers, and the clinical application of targeting miRNA-130 family has also not been established yet. Therefore, we conducted this meta-analysis to further clarify the prognostic role of the miR-130 family in cancer, and miRNA-130 family expression in cancer may act as a prognostic predictor and potential therapy target in the future.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted based on the guidelines of the meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) [32], and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [33]. In the process of constructing the prognostic value of cancer related miRNA-130 family, we rely on the help of the population, interventions, comparators, outcomes and study designs (PICOS) principle to complete the research design.

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search until July 17, 2019 using Web of Science, PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Wanfang (Chinese) and CNKI (Chinese) database. The combination terms “cancer” or “tumor” or “carcinoma” and “miRNA-130a or miRNA-130b or miRNA-130 family” and “survival” or “prognosis” or “outcome”. We also manually retrieved bibliographies of related studies that were not retrieved in the database.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusive criteria: (1) associations of expression of miRNA-130 family in cancer with OS, DFS and PFS or estimation of other survival probabilities were described, (2) patients with cancer were categorized into two groups based on high and low expression of miRNA-130 family, (3) hazard ratios (HR) with 95% CI for survival analysis were presented or could be reckoned from the instance data, (4) available in Chinese or English language. Exclusive criteria: (1) letters, reviews, expert opinions and case reports, (2) articles no available data for calculating HR with 95% CI, (3) duplicate publications.

If a study overlaps data from other published literatures, we choose to publish the latest one and/or the largest sample size.

Data extraction

Data extraction following items were extracted from the eligible studies: The name of first author, publication year, patient ages and genders, follow-up duration, sample size, pathology subtypes, clinicopathological features, OS, DFS or PFS and HR with 95% CIs. All of the information was considered as independent data sets. If HR and 95% CI were not reported, the approach of Parmar [34] and Tierney [35] was used to extrapolate the HR with 95% CI.

Methodological quality assessment

The methodological quality of eligible studies was evaluated by Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). NOS consists of three parts with a total of 9 points. Studies with NOS scores ≥ 6 points were considered as high-quality.

The specific Quality In Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) was assessed according to the method of Hayden et al. [36]. Estimates of potential bias include study participation, study attrition, prognostic factor measurement, outcome measurement, study confounding, statistical analysis, and reporting.

miRNA-130b expression profile and prognosis

The KM plotter is a pooled analysis based on biomarker evaluation, which was used to measure the effect of miRNA-130b expression levels on OS of 372 HCC patients [37].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of pooled HRs with 95% CIs were conducted by Review Manager 5.3.5 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) to assess the association between miRNA-130 family expression and prognosis. Indicators of inter-study heterogeneity were tested by the Q-tests and I-squared (I2) [38]. Based on the results of heterogeneity analysis, when P value of heterogeneity (Pheterogeneity) ≥ 0.10 or I2 ≤ 50%, a fixed-effects model (Mantel–Haenszel method) [39] was applied to calculate the pooled effect size, otherwise (Pheterogeneity < 0.1 and I2 > 50%) the random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird method) [40] was employed, and the sources of heterogeneity was explored by meta-regression in STATA 13.1MP (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) [41]. In some of the articles that do not provide HR and 95% CI, Engauge Digitizer 10.0 (https://sourceforge.net/projects/digitizer/) was utilized to extract the original survival data from the KM curves. Subgroup analyses were performed by Prognostic indicators, ethnicity (Asian, Caucasian) and cancer subtypes (pathological type). Begg’s (rank correlation test) [42] and Egger’s test (weighted linear regression test) [43] were used to evaluate the extent of publication bias.

If the 95% CI did not overlap 1, and the pooled effect size estimate of HR > 1, they would be considered statistically significant. The KM plotter split was median, and all P-values were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study identification

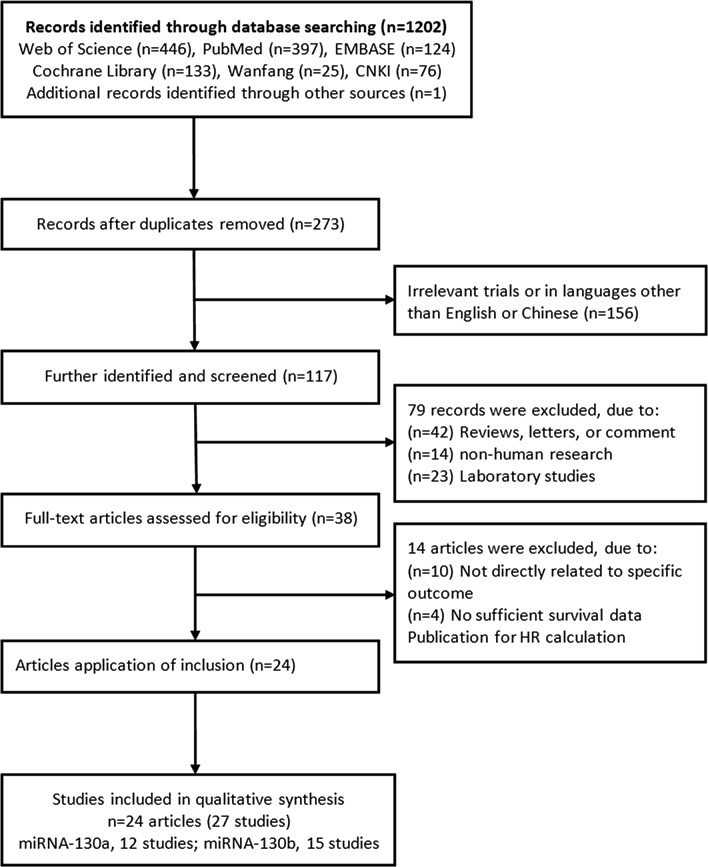

As shown in Fig. 1, a total of 1202 records were retrieved in the databases based on the search strategy. By screening the title and abstract, we excluded 929 duplicates and 156 unrelated records or language was neither English nor Chinese, and then retrieved 38 relevant full-text articles. Thirteen articles were further removed because no survival analysis results were reported and insufficient survival data were available to recalculate HR and 95% CI. Finally, 24 eligible articles (27 studies) [11, 14–18, 21–26, 30, 31, 44–53] including 12 articles [11, 14–18, 21, 44–48] for miRNA-130a and 12 articles (15 studies) [22–26, 30, 31, 49–53] for miRNA-130b were included in this meta-analysis. Three articles [23, 49, 52] included two cohort studies from different populations (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of literature search and study selection

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of eligible studies

| Study [Ref.] | Country | miRNA-130a | miRNA-130b | Histology | TNM stage | Sample | Assay | Follow-up (months) | Cut-off | HR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS | Other | OS | Other | OS | DFS/PFS | ||||||||

| Jia 2019 [44] | China | 284 | Gastric cancer | I–IV | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 50 | Median | 2.44 (1.35,4.40) | ||||

| Peng 2018 [18] | China | 333 | DFS,333 | Gastric cancer | I–III | Serum | qRT-PCR | 59 | Median | 1.49 (0.99,2.26) | 1.38 (0.99,1.91) | ||

| Liu 2018 [45] | China | 369 | Colorectal cancer | I–IV | Serum | qRT-PCR | 60 | Median | 2.36 (1.07,5.22) | ||||

| Yang 2018 [46] | China | 60 | DFS,60 | Colorectal cancer | I–IV | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 70 | Median | 2.25 (1.05,4.83) | |||

| Asukai 2017 [16] | Japan | 27 | DFS,27 | Cholangiocarcinoma | NA | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 82 | Median | 2.36 (1.18,4.17) | 2.47 (1.10,5.56) | ||

| Zhou 2017 [47] | China | 51 | HCC | I–III | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 42 | Normal | 1.23 (0.78,1.96) | ||||

| Chen 2016 [11] | China | 86 | DFS,86 | Osteosarcoma | I–IV | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 60 | Median | 2.14 (1.14,4.02) | 2.04 (1.22,3.40) | ||

| Jiang 2016 [17] | China | 41 | Gastric cancer | I–III | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 36 | Normal | 2.05 (1.03,4.08) | ||||

| Yuan 2016 [14] | China | 56 | Lymphoma | NA | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 50 | Median | 1.23 (0.94,1.61) | ||||

| He 2014 [15] | China | 73 | DFS,73 | Cervical cancer | I–IV | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 86 | Normal | 1.41 (0.30,6.63) | 1.73 (0.14,21.52) | ||

| Li 2014 [21] | China | 102 | HCC | I–III | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 72 | Normal | 0.45 (0.22,0.90) | ||||

| Wang 2012 [48] | China | DFS,100 | NSCLC | I–III | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 96 | Normal | 0.21 (0.09,0.50) | ||||

| Hashimoto 2019 [49] | America (AA) | 36 | Prostate cancer | I–IV | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 260 | Mean | 22.4 (2.27,221.3) | ||||

| America (EA) | 57 | Prostate cancer | I–IV | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 250 | Mean | 1.10 (0.21,5.74) | |||||

| Ulivi 2019 [50] | Italy | 83 | DFS,85 | NSCLC | I–IIIA | Serum | qRT-PCR | 160 | Median | 1.35 (1.08,1.69) | 1.35 (1.08,1.69) | ||

| Hu 2018 [51] | China | 110 | HCC | NA | Serum | qRT-PCR | 60 | Median | 6.58 (3.04,14.24) | ||||

| Ecke 2017 [52] | Germany (TC) | 100 | Bladder-cancer | NA | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 156 | Median | 0.99 (0.82,1.20) | ||||

| Germany (VC) | 56 | Bladder-cancer | NA | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 156 | Median | 1.02 (0.53,1.96) | |||||

| Li 2017 [22] | China | 85 | Glioma | NA | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 36 | Mean | 2.22(1.38,3.56) | ||||

| Chang 2016 [23] | China (TC) | 85 | DFS,85 | HCC | I–III | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 66 | Normal | 1.01 (0.38,2.72) | 2.02 (1.33,3.07) | ||

| China (VC) | 65 | DFS,65 | HCC | I–III | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 80 | Normal | 1.93 (1.30,2.87) | 1.73 (1.16,2.58) | |||

| Sheng 2015 [24] | China | 86 | Glioma | NA | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 36 | Median | 4.39 (1.50,12.82) | ||||

| Wang 2014 [25] | China | 97 | DFS,97 | HCC | I–IV | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 60 | Median | 2.52 (1.24,5.15) | 4.00 (1.52,10.54) | ||

| Kjersem 2014 [30] | Norway | 150 | PFS,150 | Colorectal cancer | NA | Serum | qRT-PCR | NA | Median | 1.31 (0.96,1.79) | 1.40 (1.05,1.86) | ||

| Colangelo 2013 [26] | Italy | 80 | Colorectal Cancer | I–IV | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 108 | Mean | 5.99 (1.99,18.03) | ||||

| Zhao 2013 [31] | China | 52 | Pancreatic cancer | I–IV | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 36 | Median | 2.84 (1.25,6.45) | ||||

| Nakatani 2012 [53] | Italy | 49 | Sarcoma | NA | Frozen tissue | qRT-PCR | 217 | Median | 2.11 (1.22,3.63) | ||||

NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; HCC, hepatocellular cancer; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time PCR; OS, overall survival; PFS, progressive free survival; DFS, disease free survival; SC, survival curve; AA, African-American; EA, European-American; TC,Training cohort; VC, Validation cohort

Baseline characteristics of eligible studies

The basic characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1. The articles were published from 2012 to 2019 and a total of 2141 patients with OS and 1159 patients with DFS/PFS from China, Japan, America, Germany, Norway, and Italy. The country of the study was determined based on the regional source of the subjects. The types of cancer included gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, HCC, glioma, cholangiocarcinoma, osteosarcoma, lymphoma, non-small cell lung cancer, cervical cancer, pancreatic cancer and sarcoma. The method of all miRNA-130a and miRNA-130b detection was quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). The expression of miRNA-130 family for OS and/or DFS/PFS was measured in tissue or serum. The cut-off value of miRNA-130 family expression was mostly set by median.

Assessment of methodological quality

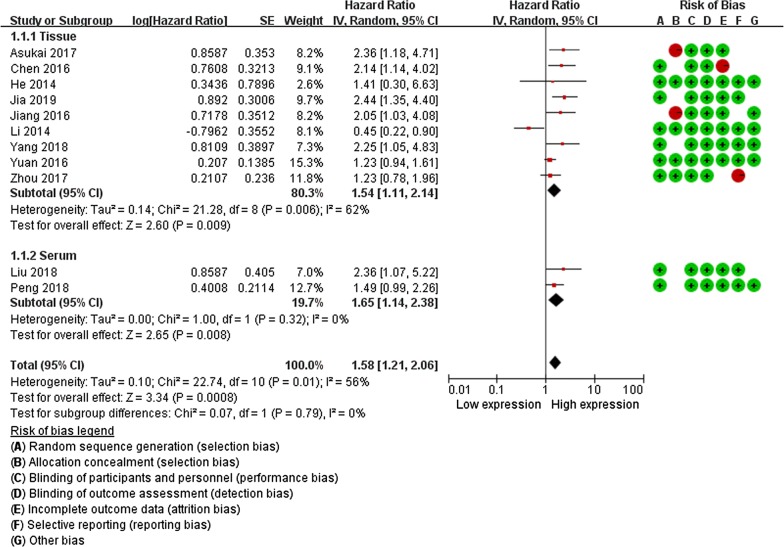

Based on QUIPS, the quality assessment for eligible studies was presented in Table 2. The risk of bias legend was summarized in Figs. 2 and 3. According to the NOS (Additional file 1: Table S1), yielded scores ranging from 5 to 9, with a mean score of 6.63, 76.0% (19/25) of these studies were considered as high-quality.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included studies based on the Quality In Prognosis Studies (QUIPS)

| Study [Ref.] | Quality evaluation of prognosis study | Total scorea | Level of evidenceb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study participation | Study attrition | Prognostic factor measurement | Outcome measurement | Study confounding | Statistical analysis and reporting | |||

| Jia 2019 [44] | Yes | Partly | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 7 | 2b |

| Peng 2018 [18] | Yes | Partly | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 7 | 2b |

| Liu 2018 [45] | Yes | Partly | Partly | Yes | Partly | Yes | 5 | 2b |

| Yang 2018 [46] | Yes | Partly | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 7 | 2b |

| Asukai 2017 [16] | Partly | Partly | Partly | Yes | Partly | Partly | 6 | 2b |

| Zhou 2017 [47] | Yes | Partly | Yes | Partly | Partly | Partly | 7 | 2b |

| Chen 2016 [11] | Yes | Partly | Yes | Partly | Partly | Partly | 5 | 2b |

| Jiang 2016 [17] | Partly | Partly | Partly | Yes | Partly | Partly | 5 | 2b |

| Yuan 2016 [14] | Yes | Partly | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 8 | 1b |

| He 2014 [15] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 8 | 1b |

| Li 2014 [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 7 | 2b |

| Wang 2012 [48] | Partly | Partly | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 6 | 2b |

| Hashimoto 2019 [49] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 8 | 1b |

| Ulivi 2019 [50] | Partly | Partly | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 6 | 2b |

| Hu 2018 [51] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partly | Partly | Partly | 9 | 2b |

| Ecke 2017 [52] | Yes | Partly | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 7 | 2b |

| Li 2017 [22] | Yes | Partly | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 7 | 2b |

| Chang 2016 [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partly | Partly | Partly | 8 | 2b |

| Sheng 2015 [24] | Partly | Partly | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 7 | 2b |

| Kjersem 2014 [30] | Partly | Partly | Yes | Partly | Partly | Partly | 6 | 2b |

| Wang 2014 [25] | Partly | Partly | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 7 | 2b |

| Colangelo 2013 [26] | Partly | Partly | Yes | Partly | Partly | Partly | 5 | 2b |

| Zhao 2013 [31] | Partly | Partly | Yes | Yes | Partly | Yes | 6 | 2b |

| Nakatani 2012 [53] | Partly | Partly | Partly | Yes | Partly | Yes | 5 | 2b |

aQuality assessment of included studies based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

bThe levels of evidence were estimated for all included studies with the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine criteria

Fig. 2.

Forest plots for the relationship between miRNA-130a expression (tissue and serum) and overall survival (OS). The squares and horizontal lines correspond to the study-specific HR and 95% CI. The area of the squares reflects the study specific weight. The diamond represents the pooled HR and 95% CI

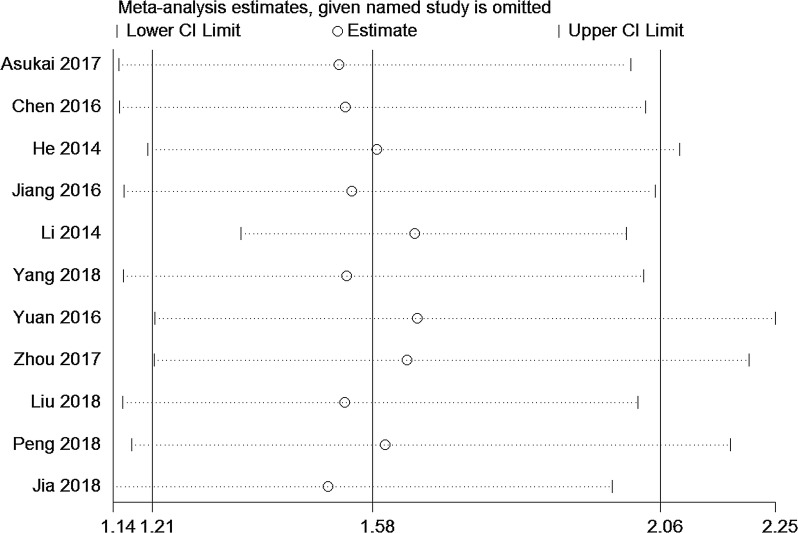

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity analysis for OS of miRNA-130a. Meta-analysis estimates, given named study is omitted for pooled results

Quantitative synthesis

The expression of miRNA-130a and patients’ survival

The observed random effect size of pooled HRs for OS were provided by 10 studies, the results indicated that the high levels of miRNA-130a expression was correlated with poor OS in cancer patients (HR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.21–2.06, P < 0.001). Tissue and serum expression of miRNA-130a was significantly correlated with the OS (HR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.11–2.14, P = 0.009; HR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.14–2.38, P = 0.008). For the subgroup differences test, the results indicated no heterogeneity between subgroups (2 = 0%, =0.79) (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Main results of pooled HRs in the meta-analysis

| Comparisons (miRNA-130 family) | Heterogeneity test | Summary HR (95% CI) | Hypothesis test | Studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | P | I2 (%) | Z | P | |||

| miRNA-130a | |||||||

| OS | |||||||

| Total | 22.74 | 0.01 | 56 | 1.58 (1.21,2.06) | 3.34 | < 0.001 | 11 |

| Tissue | 21.28 | 0.01 | 62 | 1.54 (1.11,2.14) | 2.60 | 0.009 | 9 |

| Serum | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0 | 1.65 (1.14,2.38) | 2.65 | 0.008 | 2 |

| Subgroup differences | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0 | ||||

| Cancer subtypes | |||||||

| Gastric cancer | 1.94 | 0.38 | 0 | 1.81 (1.34,2.45) | 3.83 | < 0.001 | 3 |

| Other cancers | 18.30 | 0.01 | 62 | 1.46 (1.01,2.08) | 2.11 | 0.03 | 8 |

| DFS | |||||||

| Total | 24.08 | < 0.01 | 79 | 1.35 (0.72,2.52) | 0.93 | 0.35 | 6 |

| Tissue | 23.91 | < 0.01 | 83 | 1.32 (0.52,3.40) | 0.58 | 0.56 | 5 |

| Serum | – | – | – | 1.38 (0.99,1.91) | 0.21 | 0.83 | 1 |

| Subgroup differences | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0 | ||||

| miRNA-130b | |||||||

| OS | |||||||

| Total | 60.10 | < 0.01 | 77 | 1.95 (1.47,2.59) | 4.65 | < 0.001 | 15 |

| Tissue | 44.46 | < 0.01 | 75 | 2.01 (1.39,2.91) | 3.71 | < 0.001 | 12 |

| Serum | 15.50 | < 0.01 | 87 | 1.96 (1.09,3.54) | 2.23 | 0.03 | 3 |

| Subgroup differences | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0 | ||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Asian | 12.15 | 0.06 | 51 | 2.55 (1.77,3.69) | 5.00 | < 0.001 | 7 |

| Caucasian | 23.95 | < 0.01 | 71 | 1.47 (1.08,1.99) | 2.45 | 0.01 | 8 |

| Cancer subtypes | |||||||

| HCC | 10.59 | 0.01 | 72 | 2.43 (1.28,4.63) | 8.24 | 0.004 | 4 |

| Other cancers | 30.80 | < 0.01 | 74 | 1.75 (1.30,2.37) | 3.67 | < 0.001 | 11 |

| DFS/PFS | |||||||

| Total | 7.38 | 0.12 | 46 | 1.53 (1.31,1.77) | 5.53 | < 0.001 | 5 |

| Tissue | 2.48 | 0.29 | 19 | 1.98 (1.50,2.62) | 4.85 | < 0.001 | 3 |

| Serum | 0.03 | 0.86 | 0 | 1.37 (1.15,1.64) | 3.46 | < 0.001 | 2 |

| Subgroup differences | 4.87 | 0.03 | 79.5 | ||||

| Cancer subtypes | |||||||

| HCC (DFS) | 2.48 | 0.29 | 19 | 1.98 (1.50,2.62) | 4.85 | < 0.001 | 3 |

| Other cancers | 0.03 | 0.86 | 0 | 1.37 (1.15,1.64) | 3.46 | < 0.001 | 2 |

OS, overall survival; DFS, disease free survival; PFS, progressive free survival; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma

According to cancer subtype, the subgroup analysis was performed, the results showed that high expression of miRNA-130a was significantly correlated with poor OS in gastric cancer (HR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.34–2.45, P < 0.001) and other cancer types (HR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.01–2.08, P = 0.03) (Table 3).

The pooled HRs for DFS were provided by 6 studies, there was no significant correlation between miRNA-130a expression and DFS (HR = 1.35, 95% CI: 0.72–2.52, P = 0.35), and tissue and serum expression of miRNA-130a was also not associated with the DFS (HR = 1.32, 95% CI: 0.52–3.40, P = 0.56; HR = 1.38, 95% CI: 0.99–1.91, P = 0.83) (Fig. 2, Table 3).

The expression of miRNA-130b and patients’ survival

The pooled HRs for OS were provided by 15 studies, there was a high correlation between high miRNA-130b expression and poor OS in cancer patients (HR = 1.95, 95% CI: 1.47–2.59, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3, Table 3). According to tissue and serum expression, the result indicated that a high expression of miRNA-130b significantly predicted pool OS in tissue sample (HR = 2.01, 95% CI: 1.39–2.91, P < 0.001) and serum sample (HR = 1.96, 95% CI: 1.09–3.54, P = 0.03) (Table 3). For the subgroup differences test, the results indicated that that there was heterogeneity between subgroups (2 = 0%, =0.94) (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Stratified analysis was performed based on ethnicity, the expression of miRNA-130b was significantly correlated with OS in Asian (HR = 2.55, 95% CI: 1.77–3.69, P < 0.001) and Caucasian (HR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.08–1.99, P = 0.01). Subgroup analysis was also conducted according to cancer subtype, the expression of miRNA-130b was significantly associated with OS in HCC (HR = 2.43, 95% CI: 1.28–4.63, P = 0.004) and other cancer types (HR = 1.75, 95% CI: 1.30–2.37, P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Five studies provided a combined HR of disease progression, miRNA-130b expression was significantly associated with DFS/PFS (HR = 1.53, 95% CI: 1.31–1.77, P < 0.001). Furthermore, tissue and serum expression of miRNA-130b was significantly associated with the DFS/PFS (HR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.50–2.62, P < 0.001; HR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.15–1.64, P < 0.001). Test for subgroup differences, the results showed that there was a slight heterogeneity between subgroups (2 = 79.5%, =0.03) (Table 3).

According to cancer subtype, we conducted subgroup analysis, a significant association between increased miRNA-130b and poor DFS in patients with HCC (HR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.50–2.62, P < 0.001), and DFS/PFS with other cancers (HR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.15–6.64, P < 0.001).

Test of heterogeneity

The heterogeneity of miRNA-130a for OS and miRNA-130b for subgroup differences was statistically significant (Pheterogeneity < 0.1 and I2 > 50%). Therefore, the random effects were used to calculate the HRs for miRNA-130a and miRNA-130b. Meanwhile, the meta-regression was used to explore the heterogeneous sources of miRNA-130a and miRNA-130b (Table 4).

Table 4.

The results of heterogeneity test

| Comparisons | Coef. | Std. Err. | t | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA-130a | |||||

| Language | − 0.408 | 0.382 | − 1.07 | 0.327 | − 1.342 to 0.528 |

| Publication year | − 1.272 | 0.734 | − 1.73 | 0.134 | − 3.069 to 0.525 |

| Cancer type | 0.549 | 0.710 | 0.77 | 0.469 | − 1.188 to 2.287 |

| Ethnica | – | – | – | – | – |

| Assaya | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sample size | − 0.279 | 0.372 | − 0.75 | 0.481 | − 0.630 to 1.189 |

| Follow-up | − 0.308 | 0.378 | − 0.81 | 0.446 | − 1.235 to 0.617 |

| Cut-off | − 0.506 | 0.385 | − 1.31 | 0.237 | − 1.447 to 0.436 |

| miRNA-130b | |||||

| Languagea | – | – | – | – | – |

| Publication year | 0.306 | 0.458 | 0.67 | 0.523 | − 0.751 to 1.362 |

| Cancer type | − 0.001 | 0. 542 | − 0.00 | 0.999 | − 1.250 to 1.248 |

| Ethnic | − 0.678 | 0.606 | − 112 | 0.296 | − 2.076 to 0.720 |

| Assaya | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sample size | 0.107 | 0.568 | 0.19 | 0.856 | − 1.202 to 1.416 |

| Follow-up | − 0.169 | 0.600 | − 0.28 | 0.786 | − 1.552 to 1.215 |

| Cut-off | 0.178 | 0.318 | 0.56 | 0.591 | − 0.556 to 0.912 |

a Ethnic, language and assay were dropped because of collinearity

Sensitivity analyses

To explore the stability of our results, sensitivity analysis was performed by removing one study at a time and recalculating pooled HR. The results (e.g. HR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.21–2.06) did not substantially alter the combined HRs, which indicates that our results were quite robust and stable (Fig. 3).

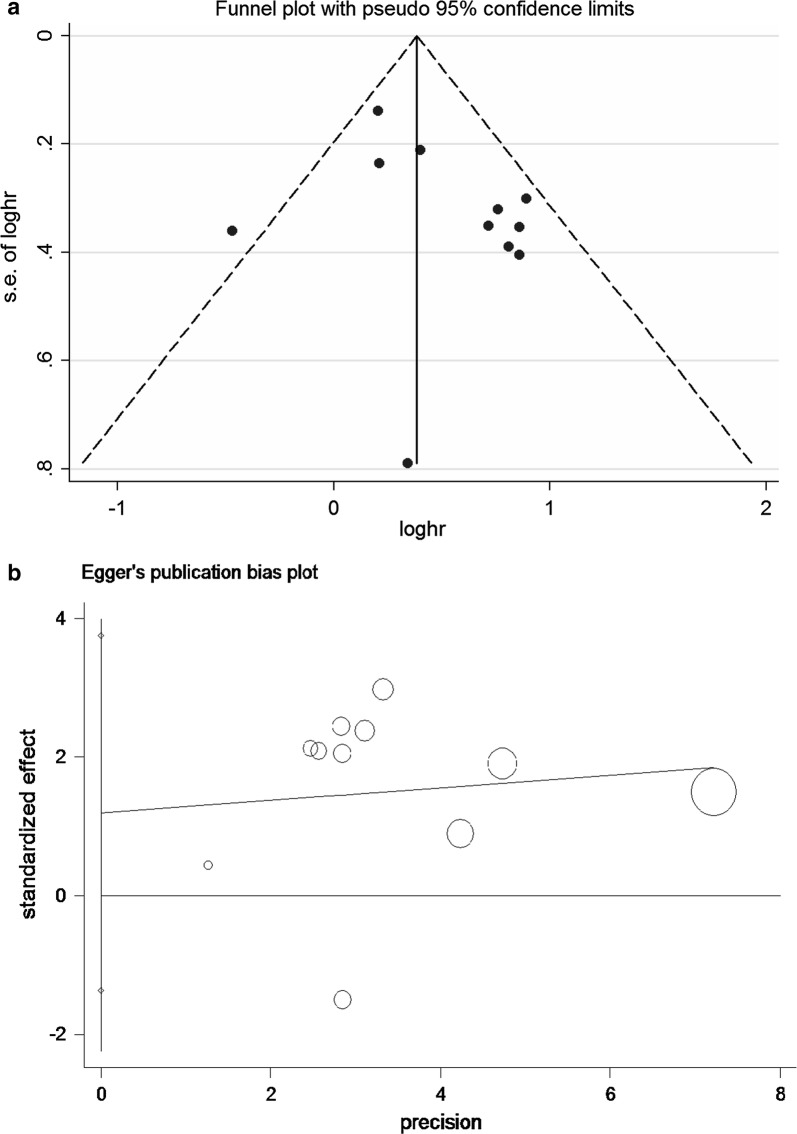

Assessment of publication bias

Begg’s and Egger’s test were applied to evaluate the publication bias. The results didn’t reveal any evidence of publication bias (Additional file 2: Table S2). Meanwhile, the funnel plots shape was basically symmetrical (Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 4.

a Begg’s funnel plot of publication bias for the association between miRNA-130a expression and OS. The vertical line in the funnel plot indicates the fixed-effects summary estimate, whereas the sloping lines indicate the expected 95% confidence intervals for a given SE. b Egger’s test of publication bias for the association between miRNA-130a expression and OS. The horizontal line in the funnel plot indicates the fixed-effects summary estimate, whereas the sloping lines indicate the expected 95% confidence intervals for a given SE

Expression of miRNA-130b and prognosis in database test

For OS, a highly significant correlation was revealed between high miRNA-130b expression and poor OS (HR = 1.55, P = 0.045) in patients with HCC (Fig. 5). The results of direct sequencing and expression of the miRNA-130b are very close to those of our combined result of individual studies.

Fig. 5.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for OS according to miRNA-130b expression in patients with HCC. OS of patients with high vs. low MMP-14 expression are shown

Discussion

Recently, accumulating evidence has demonstrated that miRNAs play an important role in cancer progression, including differentiation, proliferation, metastasis and apoptosis, and act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors [54–56]. Therefore, exploring the miRNAs involved in tumorigenesis and their target genes may contribute to understanding the underlying mechanisms of cancer patients and provide valuable clues for the early prognosis of cancer [57, 58]. The previous studies have revealed that the presence of miRNAs in the circulation may as valuable diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in some types of cancer [59, 60].

The latest advances in biomedical research facilitated the identification of a variety of molecular biomarkers that benefit cancer screening and detection, guide drug discovery, and improve survival depending on customized treatment [61]. Recently, many biomarkers have been identified that can provide important prognostic information. Nevertheless, this study is the first one to focus on the correlation between miRNA-130 family and prognosis in cancer, involving 2141 patients with OS and 1159 patients with DFS/PFS. The results provided by 12 eligible studies for miRNA-130a and 15 eligible studies for miRNA-130b, which increased expression of the miRNA-130 family predicted reduced survival in patients with cancer, indicating the prognostic value of miRNA-130 family.

The subgroup analysis indicated a closer relationship between elevated miRNA-130b expression and poor survival in the Asians (HR = 2.55, 95% CI: 1.77, 3.69). The reason may be that different dietary habits and heritage backgrounds between Asian and Western populations contribute to different survival outcomes and cancer histopathology. Among 27 studies, OS was reported in 15 types of cancer. The result revealed that increased miRNA-130 family yielded worse OS in gastric cancer (HR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.34, 2.45 for miRNA-130a) and HCC (HR = 2.43, 95% CI: 1.28, 4.63 for miRNA-130b). However, further studies are needed to explore whether the pathological types of some cancers affect the prognosis of the miRNA130 family. Due to the included studies applied different indices to evaluate cancer progression, such as DFS and PFS, we pooled the indices to assess the prognostic significance of miRNA-130 family. The results indicated a subtle correlation between high miR-130 family expression and DFS/PFS for miRNA-130b (HR = 1.53, 95% CI: 1.31, 1.77), indicating that high miRNA-130a expression may be a favorable prognostic factor in DFS/PFS, especially in HCC (DFS) (HR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.50, 2.62). However, further study is needed to confirm the role of miRNA-130 family in predicting the prognosis of different types of cancer.

In order to be able to infer reliable results, we chose to the inclusion of three studies on HCC and explored the prognostic value of miRNA-130b in GEO, EGA and TCGA, and then verified our results. We used the 372 paired HCC and normal tissues from the databases with OS and DFS data, the expression of miRNA-130b was significantly higher than that in normal control group. All these findings are further confirmed our conclusion, and indicated that miRNA-130b was validated as an independent prognostic factor for OS in HCC patients.

Invasion and migration are substantive processes for cells, and miRNA-130a has been shown to regulate invasive activities and metastatic in cancer cells [62]. Rab5a has been shown to be involved in cellular functions as an oncogene, and overexpression of miRNA-130a inhibits proliferation and apoptosis of breast cancer cells through Rab5a targeting [63]. In addition, miRNA-130a was up-regulated in gemcitabine-resistant clones of human cholangiocarcinoma cell lines, which indicated that absolute expression of miRNA-130a correlated with the viability of cholangiocarcinoma cells. The high miRNA-130a expression in the specimens of cholangiocarcinoma was closely related to poor prognosis [16]. Similar result was reported by Wang et al. [64], the findings indicated that the expression of miRNA-130A is correlated with tumor recurrence or distant organ metastasis and can be used for clinical prognosis and early diagnosis of patients with breast cancer.

The published studies have shown that miRNA-130b has a variety of biological functions, including promoting mesenchymal stem cells aging of bladder and colorectal cancer [6, 65], enhancing drug resistance of ovarian cancer cells, enhancing cell motility and downregulating thyroid hormones [66]. The miRNA-130b dysregulation are related to properties and many biological properties, the possible molecular mechanism and function of miRNA-130b inglioma cells, compared with the level of normal tissues of certain cancer types, with the increase of histological grade of glioma, the expression of microRNA-130b increased significantly [24]. Recently, miRNA-130b regulates the differentiation and proliferation of embryonic neural progenitor cells by targeting the X-linked fragile X mental retardation 1 gene [67], it has been identified as a reliable biomarker of glioma with significant prognostic value [29], our study bear out this experimental results. Thus, our results demonstrated that miRNA130 family may promote cancer growth with prognostic signifcance and can potentially be used as a novel drug target in the future.

Although our study is robust, there were some limitations. Firstly, because not all included studies provide the multivariate adjusted HRs, part of the HRs and 95% CI extracted from the survival curve. These calculated might be generated several tiny errors. Secondly, the cut-off values of included studies were used to assess the different miRNA-130 family expression, the true values may be different because of different algorithms. Thirdly, although there was no statistical evidence of publication bias, most eligible studies are in English, which may lead to publication bias. Finally, data on miRNA expression are obtained by different qRT-PCR methods (i.e. via SYBR green or TaqMan) or normalised upon different endogenous markers, which may influence the variation in results. In spite of above limitations, this meta-analysis about association between miRNA-130 family and cancer prognosis is certainly warranted.

Conclusion

In summary, the high expression of the miRNA-130 family is significantly associated with poor survival in cancer patients, especially in gastric cancer and HCC. In addition, expression of miRNA-130b was associated with ethnicity, especially in Asian. Our findings suggested that the high expression of miRNA-130 family may be applied as a prognostic predictor in patients with cancer. Prospectively, combining miRNA-130a and miRNA-130b may be considered as powerful prognostic predictor for clinical application.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Quality assessment of included studies based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for assessing the quality of cohort studies.

Additional file 2: Table S2 Publication bias of miRNA-130 family for Begg’s test and Egger’s test.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- HR

hazard ratios

- 95% CI

confidence intervals

- OS

overall survival

- DFS

disease-free survival

- PSF

progression-free survival

- NOS

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS)

- QUIPS

the specific Quality In Prognosis Studies

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- DTC

digestive tract cancer

- HCC

hepatocellular cancer

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed significantly to this work. FD and ZY designed and drafted the manuscript. JY and JS collected studies and summarized data. ZP and YF copyedited manuscript, did statistical work and prepared figures. All authors reviewed this draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81672917, 81373097).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhen Peng, Email: 18203685921@163.com.

Fujiao Duan, Email: fjduan@126.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12967-019-2093-y.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giessen C, Nagel D, Glas M, Spelsberg F, Lau-Werner U, Modest DP, Michl M, Heinemann V, Stieber P, Schulz C. Evaluation of preoperative serum markers for individual patient prognosis in stage I–III rectal cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:10237–10248. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang Y, Qiao G, Xu E, Xuan Y, Liao M, Yin G. Biomarkers for early diagnosis, prognosis, prediction, and recurrence monitoring of non-small cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:4527–4534. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S142149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lv C, Zhou YH, Wu C, Shao Y, Lu CL, Wang QY. The changes in miR-130b levels in human serum and the correlation with the severity of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2015;31:717–724. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schena FP, Serino G, Sallustio F. MicroRNAs in kidney diseases: new promising biomarkers for diagnosis and monitoring. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:755–763. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aris M, Barrio MM. Combining immunotherapy with oncogene-targeted therapy: a new road for melanoma treatment. Front Immunol. 2015;6:46. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Si-Si HU, Ling ZQ, Ming-Hua GE. Research Progress in the Effect of microRNA-130 on Carcinoma. China Cancer. 2014;23:137–140. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Y, Li R, Yu H, Wang R, Shen Z. microRNA-130a is an oncomir suppressing the expression of CRMP4 in gastric cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:3893–3905. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S139443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Chen J, Yan D, Wu W, Zhu J, Ye W, Shu Q. MicroRNA-130a promotes the metastasis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of osteosarcoma by targeting PTEN. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:3285–3292. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei H, Cui R, Bahr J, Zanesi N, Luo Z, Meng W, Liang G, Croce CM. miR-130a deregulates PTEN and stimulates tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2017;77:6168–6178. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Zhang X, Tang W, Lin Z, Xu L, Dong R, Li Y, Li J, Zhang Z, Li X, et al. miR-130a upregulates mTOR pathway by targeting TSC1 and is transactivated by NF-kappaB in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:2089–2100. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan WX, Gui YX, Na WN, Chao J, Yang X. Circulating microRNA-125b and microRNA-130a expression profiles predict chemoresistance to R-CHOP in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:423–432. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He L, Wang HY, Zhang L, Huang L, Li JD, Xiong Y, Zhang MY, Jia WH, Yun JP, Luo RZ, Zheng M. Prognostic significance of low DICER expression regulated by miR-130a in cervical cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1205. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asukai K, Kawamoto K, Eguchi H, Konno M, Asai A, Iwagami Y, Yamada D, Asaoka T, Noda T, Wada H, et al. Micro-RNA-130a-3p regulates gemcitabine resistance via PPARG in cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:2344–2352. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5871-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang H, Yu WW, Wang LL, Peng Y. miR-130a acts as a potential diagnostic biomarker and promotes gastric cancer migration, invasion and proliferation by targeting RUNX3. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:1153–1161. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng W, Liu YN, Zhu SQ, Li WQ, Guo FC. The correlation of circulating pro-angiogenic miRNAs’ expressions with disease risk, clinicopathological features, and survival profiles in gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 2018;7:3773–3791. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boll K, Reiche K, Kasack K, Morbt N, Kretzschmar AK, Tomm JM, Verhaegh G, Schalken J, von Bergen M, Horn F, Hackermuller J. MiR-130a, miR-203 and miR-205 jointly repress key oncogenic pathways and are downregulated in prostate carcinoma. Oncogene. 2013;32:277–285. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X, Zhao M, Huang J, Li Y, Wang S, Harrington CA, Qian DZ, Sun XX, Dai MS. microRNA-130a suppresses breast cancer cell migration and invasion by targeting FOSL1 and upregulating ZO-1. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:4945–4956. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li B, Huang P, Qiu J, Liao Y, Hong J, Yuan Y. MicroRNA-130a is down-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and associates with poor prognosis. Med Oncol. 2014;31:230. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li P, Wang X, Shan Q, Wu Y, Wang Z. MicroRNA-130b promotes cell migration and invasion by inhibiting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in human glioma. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:2615–2622. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang RM, Xu JF, Fang F, Yang H, Yang LY. MicroRNA-130b promotes proliferation and EMT-induced metastasis via PTEN/p-AKT/HIF-1alpha signaling. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:10609–10619. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4919-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheng X, Chen H, Wang H, Ding Z, Xu G, Zhang J, Lu W, Wu T, Zhao L. MicroRNA-130b promotes cell migration and invasion by targeting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in human glioma. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015;76:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang WY, Zhang HF, Wang L, Ma YP, Gao F, Zhang SJ, Wang LC. High expression of microRNA-130b correlates with poor prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:160. doi: 10.1186/s13000-014-0160-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colangelo T, Fucci A, Votino C, Sabatino L, Pancione M, Laudanna C, Binaschi M, Bigioni M, Maggi CA, Parente D, et al. MicroRNA-130b promotes tumor development and is associated with poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Neoplasia. 2013;15:1086–1099. doi: 10.1593/neo.13998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai KW, Koh KX, Loh M, Tada K, Subramaniam MM, Lim XY, Vaithilingam A, Salto-Tellez M, Iacopetta B, Ito Y, et al. MicroRNA-130b regulates the tumour suppressor RUNX3 in gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1456–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen H, Yang Y, Wang J, Shen D, Zhao J, Yu Q. miR-130b-5p promotes proliferation, migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells via targeting RASAL1. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:6361–6367. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malzkorn B, Wolter M, Liesenberg F, Grzendowski M. Stühler K, Meyer HE, Reifenberger G: identification and functional characterization of microRNAs involved in the malignant progression of gliomas. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:539–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kjersem JB, Ikdahl T, Lingjaerde OC, Guren T, Tveit KM, Kure EH. Plasma microRNAs predicting clinical outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer patients receiving first-line oxaliplatin-based treatment. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao G, Zhang JG, Shi Y, Qin Q, Liu Y, Wang B, Tian K, Deng SC, Li X, Zhu S, et al. MiR-130b is a prognostic marker and inhibits cell proliferation and invasion in pancreatic cancer through targeting STAT3. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e73803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815–2834. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::AID-SIM110>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayden JA, Windt DA, Der Van, Cartwright JL, Pierre CT, Claire B. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:280. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagy Á, Lánczky A, Menyhárt O, Győrffy B. Validation of miRNA prognostic power in hepatocellular carcinoma using expression data of independent datasets. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9227. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27521-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dersimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson SG, Higgins JP. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med. 2002;21:1559–1573. doi: 10.1002/sim.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jia J, Zhang X, Zhan D, Li J, Li Z, Li H, Qian J. LncRNA H19 interacted with miR-130a-3p and miR-17-5p to modify radio-resistance and chemo-sensitivity of cardiac carcinoma cells. Cancer Med. 2019;8:1604–1618. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu X, Pan B, Sun L, Chen X, Zeng K, Hu X, Xu T, Xu M, Wang S. Circulating exosomal miR-27a and miR-130a act as novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27:746–754. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang HP, Zhang Y, Sang JZX. Expression of microRNA-130a in colorectal cancer and its relationship with prognosis. Chin J Clin Oncol Rehab. 2018;25:641–644. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou ZG. WAng R, Li YM, Yang Y, Su G, Zhao YF, Wu Q, Sun GP: expression and clinical significance of mir-130a-3p and Smad 4 in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Anhui Med Univ. 2017;52:383–387. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Sun X, Cui Y. Expression and significance of microRNA-130a in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res Prev Treat. 2012;106:260–266. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hashimoto Y, Shiina M, Dasgupta P, Kulkarni P, Kato T, Wong RK, Tanaka Y, Shahryari V, Maekawa S, Yamamura S, et al. Up-regulation of miR-130b contributes to risk of poor prognosis and racial disparity in African-American prostate cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2019;12:585–598. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-18-0509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ulivi P, Petracci E, Marisi G, Baglivo S, Chiari R, Billi M, Canale M, Pasini L, Racanicchi S, Vagheggini A, et al. Prognostic role of circulating miRNAs in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Med. 2019;8:131. doi: 10.3390/jcm8020131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu XY, Li L, Wu HT, Liu Y, Wang BD, Tang Y. Serum miR-130b level, an ideal marker for monitoring the recurrence and prognosis of primary hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation treatment. Pathol Res Pract. 2018;214:1655–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ecke TH, Stier K, Weickmann S, Zhao Z, Buckendahl L, Stephan C, Kilic E, Jung K. miR-199a-3p and miR-214-3p improve the overall survival prediction of muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients after radical cystectomy. Cancer Med. 2017;6:2252–2262. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakatani F, Ferracin M, Manara MC, Ventura S, Del Monaco V, Ferrari S, Alberghini M, Grilli A, Knuutila S, Schaefer KL, et al. miR-34a predicts survival of Ewing’s sarcoma patients and directly influences cell chemo-sensitivity and malignancy. J Pathol. 2012;226:796–805. doi: 10.1002/path.3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cho WC. OncomiRs: the discovery and progress of microRNAs in cancers. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:60. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cho WC. MicroRNAs: potential biomarkers for cancer diagnosis, prognosis and targets for therapy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1273–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duan F, Wang K, Dai L, Zhao X, Feng Y, Song C, Cui S, Wang C. Prognostic significance of low microRNA-218 expression in patients with different types of cancer: evidence from published studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4773. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bryant RJ, Pawlowski T, Catto JWF, Marsden G, Vessella RL, Rhees B, Kuslich C, Visakorpi T, Hamdy FC. Changes in circulating microRNA levels associated with prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:768–774. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Browne G, Taipaleenmäki H, Stein GS, Stein JL, Lian JB. MicroRNAs in the control of metastatic bone disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Joosse SA, Müller V, Steinbach B, Pantel K, Schwarzenbach H. Circulating cell-free cancer-testis MAGE-A RNA, BORIS RNA, let-7b and miR-202 in the blood of patients with breast cancer and benign breast diseases. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:909–917. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zampetaki A, Kiechl S, Drozdov I, Willeit P, Mayr U, Prokopi M, Mayr A, Weger S, Oberhollenzer F, Bonora E. Plasma MicroRNA Profiling Reveals Loss of Endothelial MiR-126 and Other MicroRNAs in Type 2 Diabetes. Circ Res. 2010;107:810. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cho WCS. Methods of cancer diagnosis, therapy, and prognosis. Dordrecht: Springer; 2010. Cancer biomarkers (an overview) pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang HD, Jiang LH, Sun DW, Li J, Ji ZL. The role of miR-130a in cancer. Breast Cancer. 2017;24:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s12282-016-0744-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pan Y, Wang R, Zhang F, Chen Y, Lv Q, Long G, Yang K. MicroRNA-130a inhibits cell proliferation, invasion and migration in human breast cancer by targeting the RAB5A. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:384–393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang M, Ji S, Shao G, Zhang J, Zhao K, Wang Z, Wu A. Effect of exosome biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis of breast cancer patients. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20:906–911. doi: 10.1007/s12094-017-1805-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jianfeng XU, Huang Z, Lin LI, Mingqiang FU, Song Y, Shen Y, Ren D, Gao Y, Yangang SU, Zou Y. miRNA-130b is required for the ERK/FOXM1 pathway activation-mediated protective effects of isosorbide dinitrate against mesenchymal stem cell senescence induced by high glucose. Int J Mol Med. 2015;35:59–71. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin YH, Wu MH, Liao CJ, Huang YH, Chi HC, Wu SM, Chen CY, Tseng YH, Tsai CY, Chung IH. Repression of microRNA-130b by thyroid hormone enhances cell motility. J Hepatol. 2015;62:1328–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gong X, Zhang K, Wang Y, Wang J, Cui Y, Li S, Luo Y. MicroRNA-130b targets Fmr1 and regulates embryonic neural progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;439:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.08.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Quality assessment of included studies based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for assessing the quality of cohort studies.

Additional file 2: Table S2 Publication bias of miRNA-130 family for Begg’s test and Egger’s test.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.