Abstract

Background

Stage II colorectal cancer with microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) has been proven to have a better prognosis. However, in advanced stage, this trend remains controversial. This study aimed to explore the prognostic role of MSI-H in stage III and IV colorectal cancer (CRC) through meta-analysis.

Methods

A comprehensive search was performed in PubMed, Cochrane Central Library, and Embase databases. All randomized clinical trials and non-randomized studies were included based on inclusion and exclusion criteria and on survival after a radical operation with or without chemotherapy. The adjusted log hazard ratios (HRs) were used to estimate the prognostic value between MSI-H and microsatellite-stable CRCs. The random-effects model was used to estimate the pooled effect size.

Results

Thirty-six studies were included. Randomized controlled trials (RCT) and non-RCT were analyzed separately. For stage III CRCs, pooled HR for overall survival (OS) was 0.96 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.75–.123) in the RCT subgroup and 0.89 (95% CI 0.62–1.28) in the non-RCT subgroup. For disease-free survival (DFS), the HR for the RCT group was 0.83 (95% CI 0.65–1.07), similar to the non-RCT subgroup (0.83, 95% CI 0.65–1.07). Disease-specific survival (DSS) was also calculated, which had an HR of 1.07 (95% CI 0.68–1.69) in the non-RCT subgroup. All these results showed that MSI-H has no beneficial effects in stage III CRC. For stage IV CRC, the HR for OS in the RCT subgroup was 1.23 (95% CI 0.92–1.64) but only two RCTs were included. For non-RCT study, the combined HR for OS and DFS was 1.10 (95% CI 0.77–1.51) and 0.72 (95% CI 0.53–0.98), respectively, suggesting the beneficial effect for DFS and non-beneficial effect for OS.

Conclusion

For stage III CRC, MSI-H had no prognostic effect for OS, DFS, and DSS. For stage IV CRC, DFS showed a beneficial result, whereas OS did not; however, the included studies were limited and needed further exploration.

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide [1]. Due to the heterogeneity of the disease, various factors are proven to be associated with the prognosis in CRC patients. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) program classified CRC into two large groups: chromosomal instability (CIN) and microsatellite instability (MSI) [2]. MSI is the alteration of the size of nucleotide repeat sequence named microsatellites, which is caused by the loss-of-function of mismatched repair (MMR) gene; leading to the inability to repair DNA mismatches and accounted for approximately 15 to 20% of CRC patients.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines [3] stated that stage II MSI-H patients have a better prognosis and do not benefit from fluorouracil (5-FU) adjuvant therapy [4]. Unlike microsatellite-stable (MSS) CRCs, MSI-H not only had a much more active immune microenvironment with greater tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), but also showed cancer-specific upregulation of inhibitory checkpoints including programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and CTLA4 [5]. Therefore, unlike MSS CRCs, MSI-H CRCs showed a much better response to checkpoint immunotherapy. It is interesting to note that there are lots of controversies about whether microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) is a good prognostic factor in stage III and stage IV CRC patients. Some studies proved that MSI-H is still a beneficial factor with better oncological survival [6, 7]. However, several researches came to opposite conclusions, indicating MSI-H as an adverse factor for both overall survival (OS) and cancer-related survival [8].

MSI status can be confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the results of MSI-H or MSS. However, the PCR method is expensive and complicated, while immunohistochemistry(IHC) method is cheap, convenient, and widely used [9]. IHC can prove whether there is a mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) that indicates a similar situation as MSI-H, and previous research has proved that these two methods have excellent agreement [10].

In order to further explore the prognostic value of MSI-H in stage III and stage IV colorectal cancer patients, a comprehensive meta-analysis was performed.

Materials and methods

Two authors searched the PubMed electronic database, Cochrane Central Library database, and Embase for available articles that were published before July 2018. Search terms covered four aspects considering the variants of the following keywords, which included “colorectal cancer,” “microsatellite instability,” “advanced stage,” and “survival.” The PubMed search terms are listed as follows: (((((((Colonic Neoplasms) OR Colorectal Neoplasms) OR Colorectal cancer) OR colon cancer)) AND (((((Microsatellite Instability) OR Microsatellite Repeats) OR MSI) OR Mismatch repair) OR dMMR)) AND (((((((Neoplasm Metastasis) OR lymphatic metastasis) OR late stage) OR stage III OR stage IV OR advanced stage) OR metastasis)) AND ((((((prognosis) OR mortality) OR survival) OR OS) OR DFS) OR outcome). The search strategy was modified accordingly for the Cochrane Central Library database and Embase.

Inclusion criteria were listed as follows:

Original articles, with retrievable survival data in full text or abstract, that compare the clinical outcome between MSI-H and MSS in stage III or stage IV CRC.

From the abstract or full text, hazard ratio (HR) of OS, disease-free survival (DFS), or other survival rates between MSI-H and MSS groups, can be acquired, or calculated.

Also, research that matched any of the criteria below were excluded to prevent bias.

Patients who received immunotherapy such as anti-PD-1 or anti-programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) treatment.

When the number of patients in the MSI-H group was less than 9.

Research that included other factors (such as BRAF status) that mixed with microsatellite status and could not calculate the HR separately.

The search and analysis procedures were performed by two authors separately. If multiple researches were used to investigate the patients in the same clinical trial or medical institution, the latest or largest one will be included in order to prevent overlapping. We also excluded letters, review articles, and case reports. If the two authors had a disagreement, a third reviewer made the decision.

The included studies comprised of both RCT and non-RCT studies; therefore, both Cochrane and Newcastle–Ottawa scale were used to assess the methodological quality

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

Considering the different clinical survivals in stage III and IV CRC, the analysis for OS, DFS, and disease-specific survival (DSS) were performed separately according to the different stages.

The adjusted log hazard ratios (HRs) were used to estimate the prognostic value between MSI-H and MSS CRCs. The HRs were extracted from the Cox proportional hazards regression model provided in the included articles. For studies that failed to provide the HR value between MSI-H and MSS groups but provided the Kaplan-Meier survival curves, Engauge Digitizer (Version 4.1) was used to extract the survival information from the curve while HR was calculated by the method provided by Tierney et al. [11]

Meta-analysis was performed between MSI-H and MSS patients to explore the relationship between microsatellite status and clinical prognosis, using Stata version 14.0 (Stata, College Station, TX).

Heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic. The random-effects model was conducted to estimate the pooled effect size of OS, DFS, and DSS. Funnel plots were performed in every analysis to examine publication bias. Sensitivity analysis was also performed in every subgroup analysis. Meta-regression analysis was performed to control for heterogeneity. The DFS is usually defined based on the “study entry till documented progression or death from any cause,” while relapse-free survival (RFS) and progression-free survival (PFS) showed similar endpoints. Therefore, these data were analyzed together. For the same season, we combined the DSS and cancer-specific survival (CSS).

The RCT studies were assessed according to the Cochrane protocol. The non-RCT studies were assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale which considers participant selection, comparability, and outcome with a full score of 9. A score higher than 6 was considered to be of good quality for the individual study.

Results

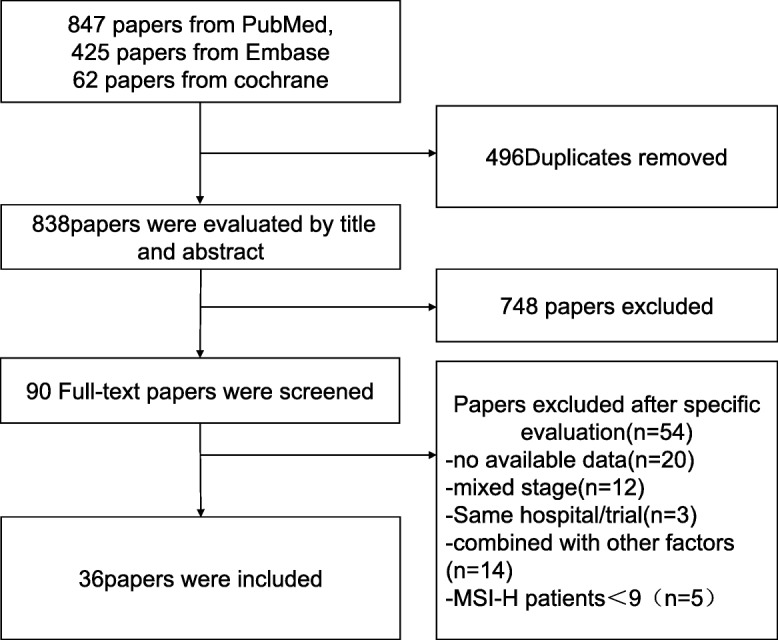

Overall, 847, 425, and 62 studies were retrieved from PubMed electronic database, Embase, and Cochrane Library, respectively. After the removal of duplicate articles, a total of 838 papers that matched the inclusion criteria were found. In total, 748 papers were excluded following the reading of the title and abstract. The full text of the remaining 90 articles was carefully read by two authors. Several researches were excluded due to the inability to acquire the specific survival data. Finally, 36 articles, that provided specific survival information, were included in this meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of researches screening

Characteristics of the studies

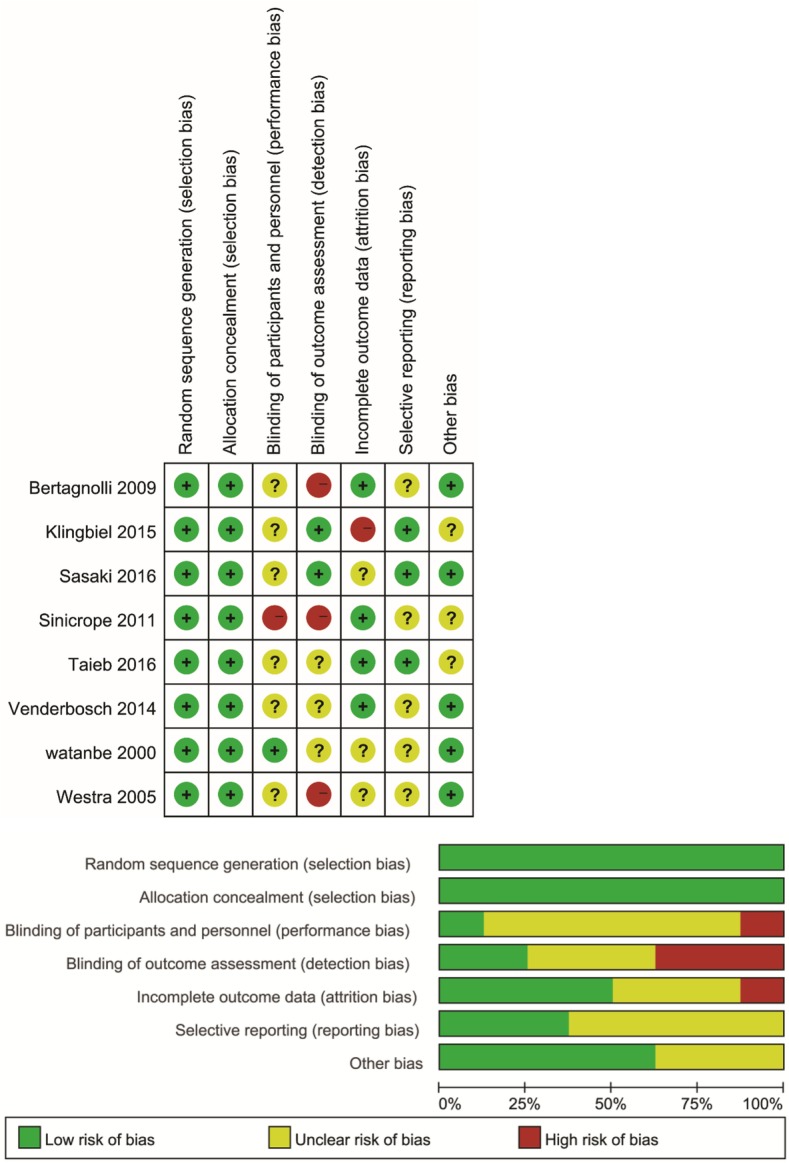

The characteristics of the studies are summarized in Table 1. For stage III CRC, seven [6, 8, 10, 33, 34, 36, 39] RCTs had survival information for both OS and DFS; and an extra article [40] was available for DFS analysis. There were 13 [7, 15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 23, 25, 29, 32, 41, 43, 44] non-RCT studies that provided information on OS HR or available data while 11 [15, 18, 19, 21, 23–25, 32, 37, 42, 43] were found for DFS analysis. Five researches [13, 20, 28, 29, 37] also provided DSS/CSS information. For stage IV, only two RCTs [30, 31] for OS were available, with eight non-RCTs [12, 14, 17, 22, 25–27, 38]. No available RCT data for DFS analysis and five non-RCT [22, 25–27, 30] articles were included. Five studies [13, 20, 28, 29, 37] have CSS/DSS information and were analyzed together. The MSI could be measured by both PCR and IHC, different researches performed different methods as shown in Table 1. Cochrane risk of bias and Newcastle–Ottawa scale results are shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2; both of them showed no obvious risk of bias.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Country | Year | Study design | Stage | Total no. | MSI-H | MSS | MSI determination | Survival information | Chemotherapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alex, A.K [12] | Brazil | 2017 | Non-RCT | IV | 126 | 42 | 84 | IHC + PCR | OS | Oxaliplatin-based |

| Bertagnolli [10] | USA | 2009 | RCT | III | 702 | 96 | 606 | IHC + PCR | OS, DFS | FU/LV/IFL |

| Chouhan [13] | Australia | 2018 | Non-RCT | III | 686 | 95 | 591 | IHC + PCR | CSS | NA |

| des Guetz [14] | France | 2007 | Non-RCT | IV | 40 | 9 | 31 | PCR | OS | FOLFOX |

| Drucker [15] | Canada | 2013 | Non-RCT | III | 159 | 18 | 141 | IHC + PCR | OS, DFS | FOLFOX/capecitabine |

| Elsaleh [16] | Australia | 2001 | Non-RCT | III | 732 | 63 | 669 | PCR | OS | 5-FU/levamisole |

| Fujiyoshi [17] | Japan | 2017 | Non-RCT | IV | 401 | 15 | 386 | PCR | OS | NA |

| Guidoboni [7] | Italy | 2001 | Non-RCT | III | 54 | 20 | 34 | PCR | OS | 5-FU |

| Hemminki [18] | Finland | 2000 | Non-RCT | III | 95 | 11 | 84 | PCR | OS, DFS | 5-FU-based |

| Jover [19] | Spain | 2006 | Non-RCT | III | 209 | 18 | 191 | IHC + PCR | OS, DFS | 5-FU-based |

| Jung [20] | Korea | 2016 | Non-RCT | III | 60 | 19 | 41 | PCR | CSS | NA |

| Kim, C.G [21]. | Korea | 2016 | Non-RCT | III | 2940 | 261 | 2679 | PCR | OS, DFS | 5-FU/LV/FOLFOX |

| Kim, J.E [22]. | Korea | 2011 | Non-RCT | IV | 197 | 23 | 174 | IHC + PCR | OS, DFS | FOLFIRI/XELIRI |

| Kim, J.E [23]. | Korea | 2017 | Non-RCT | III and IV | 795 | 73 | 722 | PCR | OS, DFS | FOLFOX |

| Kim, S.H [24]. | Korea | 2013 | Non-RCT | III | 394 | 26 | 368 | PCR | DFS | FOLFOX |

| Klingbiel, D [6]. | Switzerland | 2015 | RCT | III | 859 | 104 | 755 | PCR | OS, DFS | 5-FU/LV/FOLFIRI |

| Li, P [25]. | China | 2017 | Non-RCT | III and IV | 599 | 54 | 545 | IHC | OS, DFS | FOLFOX/XELOX |

| Liu [26] | China | 2018 | Non-RCT | IV | 461 | 30 | 431 | IHC + PCR | OS, DFS | NA |

| Ma, J [27]. | China | 2015 | Non-RCT | IV | 184 | 34 | 150 | IHC | OS, PFS | FOLFIRI/irinotecan |

| Malesci, A [28]. | Italy | 2007 | Non-RCT | III | 264 | 27 | 237 | PCR | DSS | 5-FU |

| Mohan, H.M [29]. | Ireland | 2016 | Non-RCT | III | 320 | 32 | 288 | IHC + PCR | OS, DSS | NA |

| Nopel-Dunnebacke [30] | Germany | 2014 | RCT | IV | 204 | 14 | 190 | IHC + PCR | OS, PFS | CAPOX/FUFOX |

| Nordholm-Carstensen [31] | Denmark | 2015 | RCT | IV | 935 | 75 | 860 | IHC | OS | NA |

| Oh, S.Y [32]. | Korea | 2013 | Non-RCT | III | 127 | 16 | 111 | PCR | OS, DFS | FOLFOX |

| Sasaki, Y [33]. | Japan | 2016 | RCT | III | 304 | 23 | 281 | IHC | OS, RFS | UFT |

| Sinicrope, F. A [34] | USA | 2011 | RCT | III | 1363 | 180 | 1183 | IHC + PCR | OS, DFS | 5-FU-based |

| Sinicrope, F.A [35]. | USA | 2013 | RCT | III | 2580 | 314 | 2266 | IHC + PCR | DFS | FOLFOX-based |

| Taieb, J [36]. | France | 2016 | RCT | III | 1791 | 177 | 1614 | IHC + PCR | OS, DFS | FOLFOX ± cetuximab |

| Tan, W. J [37]. | Singapore | 2018 | Non-RCT | III | 299 | 27 | 272 | IHC | DSS, RFS | 5FU/capecitabine ± oxaliplatin |

| Tran, B [38]. | Australia | 2011 | Non-RCT | IV | 350 | 40 | 310 | IHC + PCR | OS | NA |

| Venderbosch, S [8]. | Netherlands | 2014 | RCT | III | 3063 | 153 | 2910 | IHC | OS, PFS | NA |

| Watanbe [39] | USA | 2000 | Non-RCT | III | 229 | 73 | 156 | PCR | OS, DFS | 5-FU–based |

| Westra, J. L. [40] | UK | 2005 | RCT | III | 273 | 229 | 44 | PCR | DFS | 5-FU–based |

| Wright, C.M [41]. | Australia | 2000 | Non-RCT | III | 238 | 21 | 217 | PCR | OS | NA |

| Zaanan, A [42]. | France | 2010 | Non-RCT | III | 233 | 32 | 201 | IHC + PCR | DFS | FOLFOX |

| Zaanan, A [43]. | France | 2011 | Non-RCT | III | 303 | 34 | 269 | IHC + PCR | OS, DFS | FOLFOX |

MSI-H microsatellite instability-high, MSS microsatellite stable, RCT randomized controlled trial, IHC immunohistochemistry, PCR polymerase chain reaction, OS overall survival, DFS disease-free survival, DSS disease-specific survival, CSS cancer-specific survival, RFS recurrence-free survival, FU fluorouracil, LV leucovorin, IFL irinotecan + fluorouracil + leucovorin, 5-FU 5-fluorouracil, FOLFOX 5-fluorouracil + leucovorin + oxaliplatin, FOLFIRI 5-fluorouracil + irinotecan + leucovorin, XELOX xeloda + oxaliplatin, CAPOX capecitabine + oxaliplatin, FUFOX fluorouracil + fludarabine + oxaliplatin, UFT tegafur

Fig 2.

Cochrane risk of bias analysis for included randomized controlled trial

Table 2.

Newcastle–Ottawa scale for included non-RCT studies

| Author | Year | Study design | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Alex, A.K [12] | 2017 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Chouhan [13] | 2018 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| des Guetz, G [14] | 2007 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Drucker, A [15] | 2013 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Elsaleh, H [16] | 2001 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Fujiyoshi, K [17] | 2017 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Guidoboni, M [7]. | 2001 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Hemmink i [18] | 2000 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Jover [19] | 2006 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Jung, S.H [20]. | 2016 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Kim, C. G [21]. | 2016 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Kim, J.E [23]. | 2017 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Kim, J.E [22]. | 2011 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Kim, S.H [24]. | 2013 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Lanza, G [44]. | 2006 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Li, P [25]. | 2017 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Liu [26] | 2018 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Ma, J [27]. | 2015 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Malesci, A [28]. | 2007 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Mohan, H.M [29]. | 2016 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Oh, S.Y [32]. | 2013 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Tan, W. J [37]. | 2017 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Tran, B [38]. | 2011 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Wright, C. M [41]. | 2000 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Zaanan, A [43]. | 2011 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Zaanan, A [42]. | 2010 | Non-RCT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

Data analysis

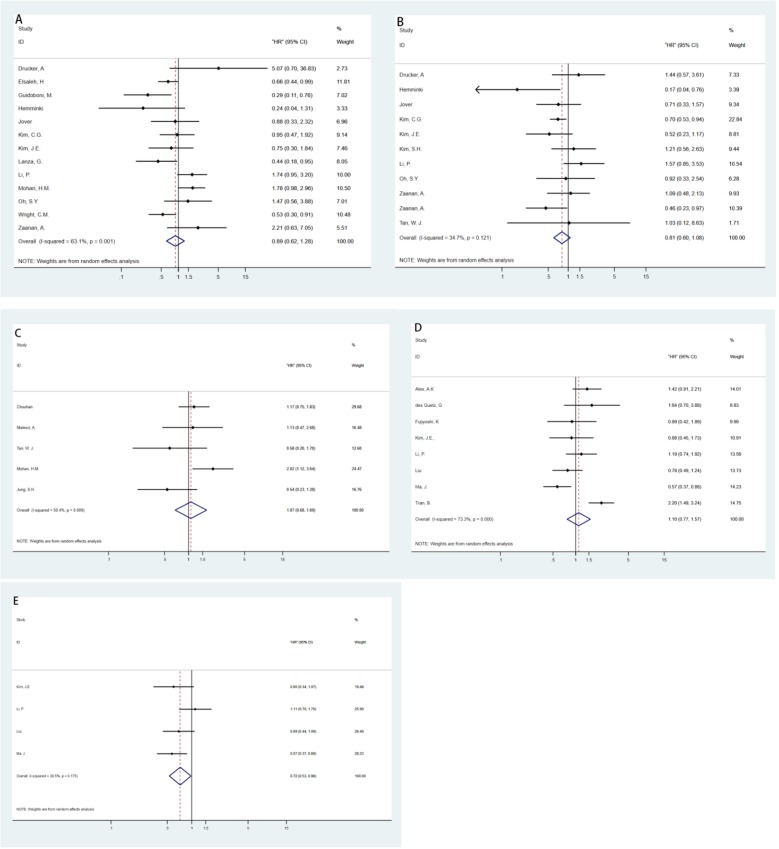

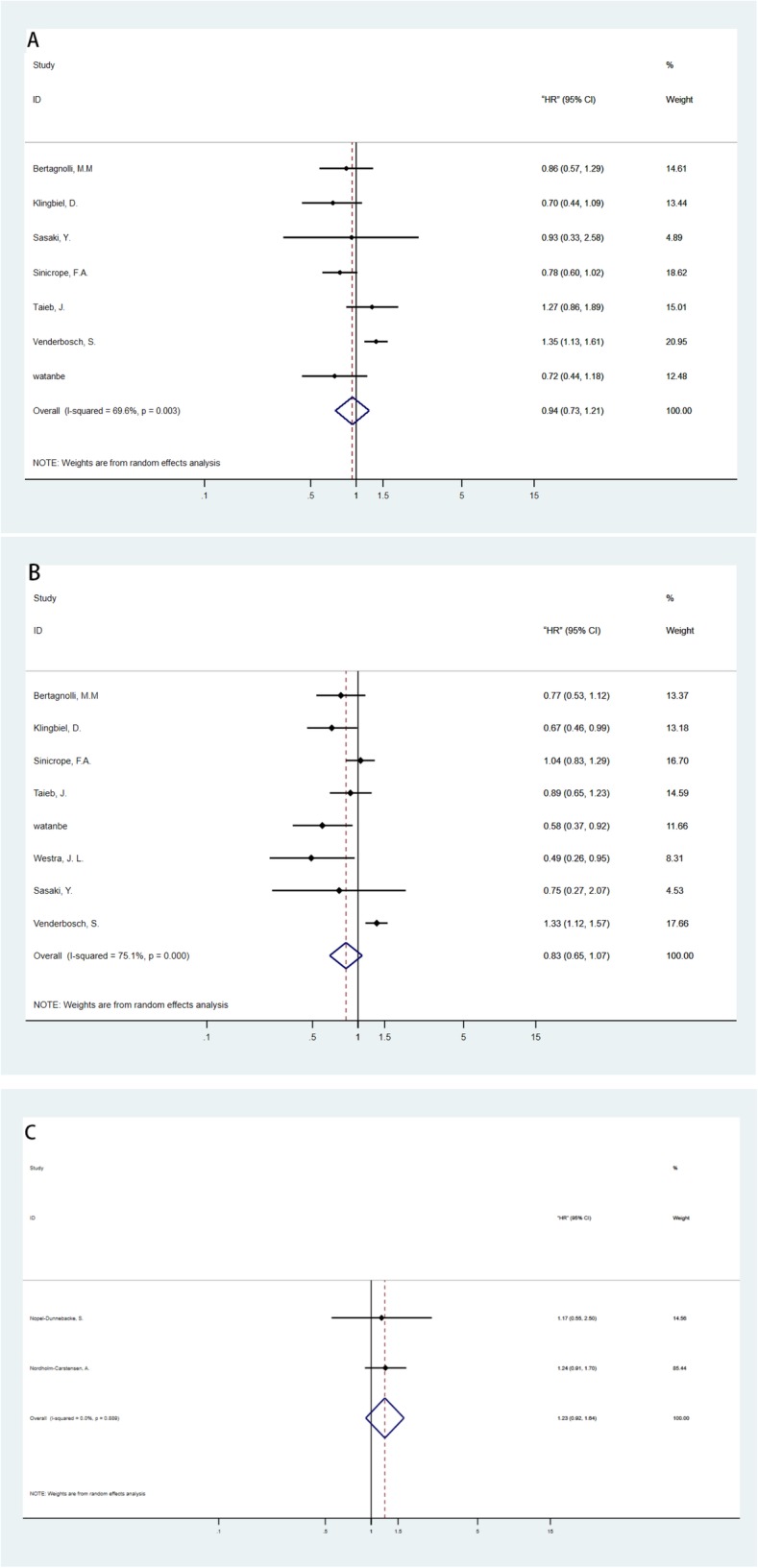

Meta-analyses were performed for every subgroup according to stage, study method, and survival information. Figure 3 shows the results of the RCTs while Fig. 4 presents the results of the non-RCTs.

Fig 3.

Meta-analysis of HRs between microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) and microsatellite-stable (MSS) CRC patients in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). a Overall survival (OS) for stage III. b Disease-free survival (DFS) for stage III. c OS for stage IV

Fig 4.

Meta-analysis of HRs between microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) and microsatellite-stable (MSS) CRC patients in non-randomized controlled trials (non-RCTs). a–c Overall survival (OS); disease-free survival (DFS); disease-specific survival (DSS) for stage III. d–e OS and DFS for stage IV

Relationship between MSI and survival

The RCT and non-RCT studies were analyzed separately both for stage III and stage IV groups. The analysis used OS, DFS, and DSS as the judging point. Since DFS, PFS, and RFS have very similar endpoints, their data were analyzed together. Also, DSS and CSS were analyzed together.

For stage III CRC, the calculated HR value of OS was 0.94 (95% CI 0.73–1.21) in RCT subgroup and 0.89 (95% CI 0.62–1.28) in non-RCT subgroup. For DFS, the RCT group showed HR of 0.83 (95% CI 0.65–1.07) similar to the non-RCT subgroup, 0.83 (95% CI 0.65–1.07). DSS was also calculated as 1.07 (95% CI 0.68–1.69) in the non-RCT subgroup. All these results showed that MSI-H had no beneficial effect in stage III CRC.

For stage IV CRC, the HR for OS in the RCT subgroup was 1.23 (95% CI 0.92–1.64) but only two RCTs were included. For non-RCT study, the combined HR for OS and DFS was 1.10 (95% CI 0.77–1.51) and 0.72 (95% CI 0.53–0.98), respectively. The pooled HR suggested a non-beneficial effect for OS. However, for DFS, the pooled results suggested a slight beneficial effect.

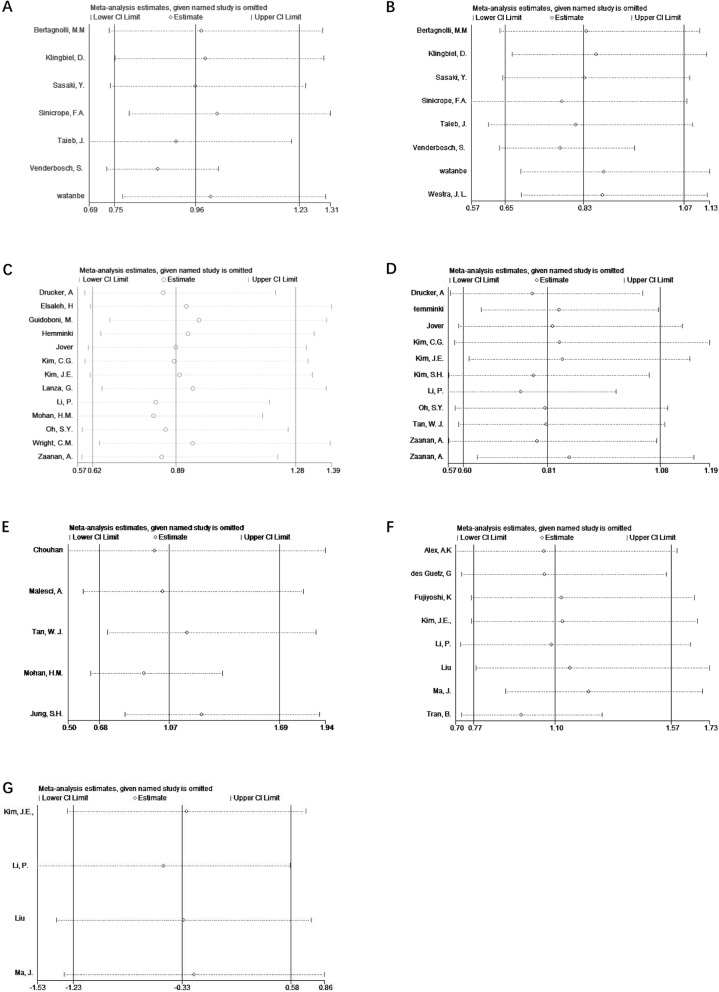

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed for all subgroups, each study was excluded to draw a new result that is shown in Fig. 5; and no obvious bias was detected in the subgroup analysis.

Fig 5.

Sensitivity analysis for included researches. a Overall survival (OS) for stage III RCT studies. b Disease-free survival (DFS) for stage III RCT studies. c OS for stage III retrospective studies. d DFS for stage III retrospective studies. e Disease-specific survival (DSS) for stage III retrospective studies. f OS for stage IV retrospective studies. g DFS for stage IV retrospective studies

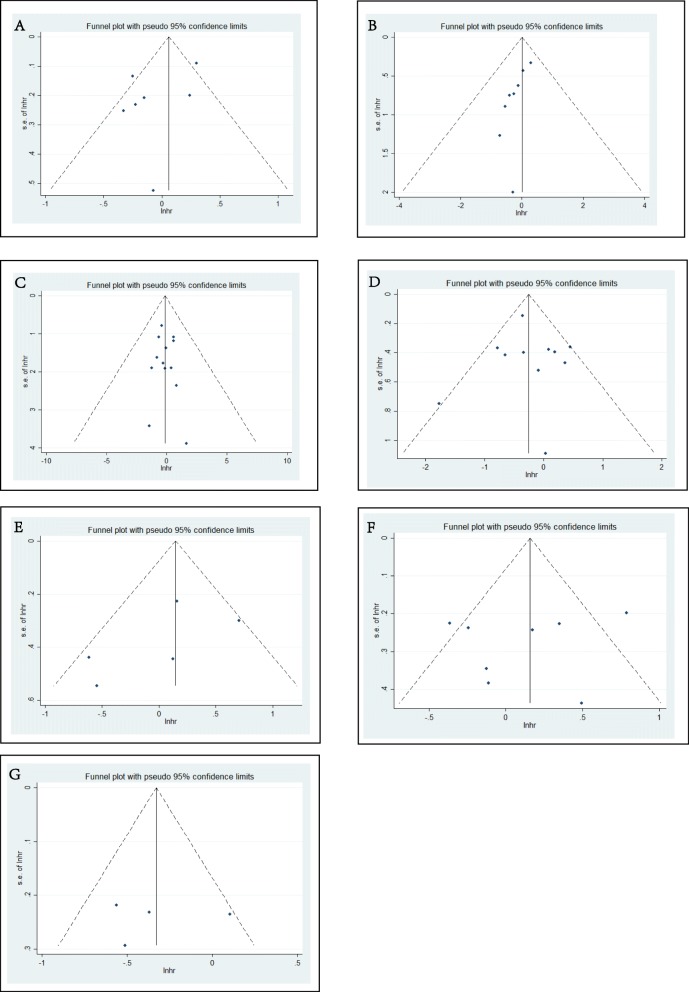

Publication bias was detected in all subgroups. The results are shown in the funnel plots (Fig. 6); and no obvious publication bias was detected.

Fig 6.

Publication bias detected by funnel plots. The funnel plots showed the HR associated with MSI in included studies of different subgroups. a Overall survival (OS) for stage III RCT studies. b Disease-free survival (DFS) for stage III RCT studies. c OS for stage III retrospective studies. d DFS for stage III retrospective studies. e Disease-specific survival (DSS) for stage III retrospective studies. f OS for stage IV retrospective studies. g DFS for stage IV retrospective studies

Since the included studies in stage IV were limited, meta-regression analysis was performed for stage III researches. Study design and year of publication were taken into consideration. The adjusted I2 was 36.55% for OS and 51.26% for DFS, suggesting study design and year of publication to be influencing factors.

Discussion

For stage III CRC, neither RCTs nor retrospective studies reached a convincing conclusion. Most included RCTs had insignificant results, except Venderbosch’s [8] research, which showed that dMMR conferred an inferior prognosis on both DFS and OS based on a series of cohort studies including 3063 patients. On the contrary, Klingbiel et al. [6] and Westra [40] studies showed MSI-H to be a good factor for DFS. The synthetized analysis turned out to be inconclusive. For non-RCTs, several researches revealed statistically significant results; however, the pooled result failed to draw a positive result.

For stage IV CRC, there were only two RCTs available [30, 31] on OS, both of which showed no positive results. Retrospective studies also showed no conclusive results of the predictive effect on OS. This indicates MSI-H/dMMR not to be predictive factor of a better prognosis. For DFS, the only RCT [30] showed no survival difference (p = 0.47) between MSI-H and MSS group. Non-RCT researches revealed a significant beneficial result, but the included researches were limited and the number of MSI-H patients was few, making the result less convincing. Another point was that the definition of stage IV was too wide and the survival rate about whether a patient can achieve “no evidence of disease” (NED) differed greatly. It was discovered that in most studies, NED patients were not separated from non-surgical patients during analysis, several studies only included unresectable patients, making the results of stage IV less convincing. Therefore, whether MSI-H is beneficial for stage IV DFS needs further exploration with large scale RCTs.

To our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the first to summarize the prognostic effect of MSI-H CRC in an advanced stage. The result showed that MSI-H may not be a good prognostic factor for stage III or stage IV CRC patients.

Although MSI-H CRC accounted for only about 15% of all CRC patients, this special molecular subtype has a distinctly different pathological manifestation including poor differentiation, accumulation of lymphocytes, and intertumoral heterogeneity. The NCCN guideline indicates that stage II MSI-H patients may have a good prognosis and do not benefit from 5-FU adjuvant therapy [3]. For stage III and IV CRC, there are disagreements on whether MSI-H is a good prognostic factor.

Recent studies [45, 46] proved that MSI-CRCs were sensitive to immune checkpoint blockade with anti-PD1 and PD-L1 antibodies. dMMR patients have much higher somatic mutations and prominent lymphocyte infiltrates. Previous studies showed that MSI-H CRCs exhibit a strong association with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and the immune reaction is strongly relevant to survival [47, 48]. This may explain why early-stage MSI-H CRCs manifest a better clinical prognosis. Furthermore, this paradoxical phenomenon can be explained by a lot of studies focused on the immune checkpoint. While MSI-H CRCs have more tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, scientists also found MSI-H tumor microenvironment strongly expressed several checkpoint ligands including PD-1 and CTLA-4. However, the active immune microenvironment is counterbalanced by immune inhibitory signals that resist tumor elimination [5]. This may explain why stage III and IV MSI-H CRC did not manifest a better survival, it might be because the immune system has completely lost the fight against tumor cells who overexpressed PD-1 and CTLA-4, and then metastasis began [49–51]. One important thing to notice is that MSI-H has a strong relevance in the upregulation of immune checkpoint, making checkpoint inhibitor a promising treatment method [52].

As mentioned above, MSI CRC accounted for about 15% of all CRC patients. However, in this meta-analysis, the percentage of MSI-H patients was 11% and 9.4% in stage III and stage IV subgroup, respectively. The lower percentage may suggest that MSI-H/dMMR CRC have a reduced potential of metastasis [28, 53], but the underlying mechanism is yet to be clarified. One plausible explanation could be the stronger immunoreaction of MSI-H cancer [54].

Several aspects of this meta-analysis warrant further discussions. For advanced-stage CRC, chemotherapy was commonly recommended, but the chemotherapy regimen has altered a lot in recent decades; this may cause different effect on MSI-H and MSS patients. Therefore, we also analyzed the prognostic effect of different chemotherapy on these subgroups of patients; but there were no significant conclusions.

There are several limitations to this meta-analysis. First, the majority included researches that were non-RCTs due to the limited number of RCTs. Secondly, there was heterogeneity between the included studies and exaggeration may still exist even with the random-effects model. On the contrary, sensitivity analysis did not show obvious change in the pooled results, suggesting an acceptable result.

Thirdly, several researches did not provide HR, and relative survival data were extracted for the article in order to calculate the approximate HR. Although mathematically practical, this may cause a slight calculation error. Lastly, the researches focusing on stage IV CRC is very limited; therefore, this may not reach a very convincing result.

In conclusion, in contrast to stage II, MSI-H CRCs showed no good prognostic effect for OS, DFS, and DSS in stage III as well as OS for stage IV CRCs patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- 5-FU

5-fluorouracil

- CAPOX

Capecitabine + oxaliplatin

- CSS

Cancer-specific survival

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- DSS

Disease-specific survival

- FOLFIRI

5-fluorouracil + irinotecan + leucovorin

- FOLFOX

5-fluorouracil + leucovorin + oxaliplatin

- FU

Fluorouracil

- FUFOX

Fluorouracil + fludarabine + oxaliplatin

- IFL

Irinotecan + fluorouracil + leucovorin

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- LV

Leucovorin

- MSI-H

Microsatellite instability-high

- MSS

Microsatellite stable

- OS

Overall survival

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- RFS

Recurrence-free survival

- UFT

Tegafur

- XELOX

Xeloda + oxaliplatin

Authors’ contributions

WF contributed to the study design. BW and FL screened the literature. BW and YM analyzed the data. BW and XZ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study received no fund support.

Availability of data and materials

All data were extracted from published articles, and the datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Bingyan Wang and Fei Li contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Ahnen DJ, Meester RGS, Barzi A, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(3):177–193. doi: 10.3322/caac.21395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson AB, 3rd, Venook AP, Cederquist L, Chan E, Chen YJ, Cooper HS, Deming D, Engstrom PF, Enzinger PC, Fichera A, et al. Colon Cancer, Version 1.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(3):370–398. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Monges G, Thibodeau SN, Labianca R, Hamilton SR, French AJ, Kabat B, Foster NR, Torri V, et al. Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(20):3219–3226. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llosa NJ, Cruise M, Tam A, Wicks EC, Hechenbleikner EM, Taube JM, Blosser RL, Fan H, Wang H, Luber BS, et al. The vigorous immune microenvironment of microsatellite instable colon cancer is balanced by multiple counter-inhibitory checkpoints. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(1):43–51. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klingbiel D, Saridaki Z, Roth AD, Bosman FT, Delorenzi M, Tejpar S. Prognosis of stage II and III colon cancer treated with adjuvant 5-fluorouracil or FOLFIRI in relation to microsatellite status: results of the PETACC-3 trial. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(1):126–132. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidoboni M, Gafa R, Viel A, Doglioni C, Russo A, Santini A, Del Tin L, Macri E, Lanza G, Boiocchi M, et al. Microsatellite instability and high content of activated cytotoxic lymphocytes identify colon cancer patients with a favorable prognosis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(1):297–304. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61695-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venderbosch S, Nagtegaal ID, Maughan TS, Smith CG, Cheadle JP, Fisher D, Kaplan R, Quirke P, Seymour MT, Richman SD, et al. Mismatch repair status and BRAF mutation status in metastatic colorectal cancer patients: a pooled analysis of the CAIRO, CAIRO2, COIN, and FOCUS studies. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(20):5322–5330. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marginean EC, Melosky B. Is there a role for programmed death ligand-1 testing and immunotherapy in colorectal cancer with microsatellite instability? Part I-Colorectal Cancer: Microsatellite Instability, Testing, and Clinical Implications. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(1):17–25. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0040-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertagnolli MM, Niedzwiecki D, Compton CC, Hahn HP, Hall M, Damas B, Jewell SD, Mayer RJ, Goldberg RM, Saltz LB, et al. Microsatellite instability predicts improved response to adjuvant therapy with irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin in stage III colon cancer: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Protocol 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(11):1814–1821. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alex AK, Siqueira S, Coudry R, Santos J, Alves M, Hoff PM, Riechelmann RP. Response to chemotherapy and prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer with DNA deficient mismatch repair. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017;16(3):228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chouhan H, Sammour T, L Thomas M, W Moore J: Prognostic significance of BRAF mutation alone and in combination with microsatellite instability in stage III colon cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.des Guetz G, Mariani P, Cucherousset J, Benamoun M, Lagorce C, Sastre X, Le Toumelin P, Uzzan B, Perret GY, Morere JF, et al. Microsatellite instability and sensitivitiy to FOLFOX treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(4c):2715–2719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drucker A, Arnason T, Yan SR, Aljawad M, Thompson K, Huang WY. Ephrin b2 receptor and microsatellite status in lymph node-positive colon cancer survival. Transl Oncol. 2013;6(5):520–527. doi: 10.1593/tlo.13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsaleh H, Powell B, McCaul K, Grieu F, Grant R, Joseph D, Iacopetta B. P53 alteration and microsatellite instability have predictive value for survival benefit from chemotherapy in stage III colorectal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(5):1343–1349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujiyoshi K, Yamamoto G, Takenoya T, Takahashi A, Arai Y, Yamada M, Kakuta M, Yamaguchi K, Akagi Y, Nishimura Y, et al. Metastatic pattern of stage IV colorectal cancer with high-frequency microsatellite instability as a prognostic factor. Anticancer Res. 2017;37(1):239–247. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemminki A, Mecklin JP, Jarvinen H, Aaltonen LA, Joensuu H. Microsatellite instability is a favorable prognostic indicator in patients with colorectal cancer receiving chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(4):921–928. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.18161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jover R, Zapater P, Castells A, Llor X, Andreu M, Cubiella J, Pinol V, Xicola RM, Bujanda L, Rene JM, et al. Mismatch repair status in the prediction of benefit from adjuvant fluorouracil chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2006;55(6):848–855. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.073015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung SH, Kim SH, Kim JH. Prognostic impact of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer presenting with mucinous, signet-ring, and poorly differentiated cells. Ann Coloproctol. 2016;32(2):58–65. doi: 10.3393/ac.2016.32.2.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim CG, Ahn JB, Jung M, Beom SH, Kim C, Kim JH, Heo SJ, Park HS, Kim JH, Kim NK, et al. Effects of microsatellite instability on recurrence patterns and outcomes in colorectal cancers. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(1):25–33. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JE, Hong YS, Ryu MH, Lee JL, Chang HM, Lim SB, Kim JH, Jang SJ, Kim MJ, Yu CS, et al. Association between deficient mismatch repair system and efficacy to irinotecan-containing chemotherapy in metastatic colon cancer. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(9):1706–1711. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JE, Hong YS, Kim HJ, Kim KP, Kim SY, Lim SB, Park IJ, Kim CW, Yoon YS, Yu CS, et al. Microsatellite instability was not associated with survival in stage III colon cancer treated with adjuvant chemotherapy of oxaliplatin and infusional 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin (FOLFOX) Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(5):1289–1294. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5682-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SH, Shin SJ, Lee KY, Kim H, Kim TI, Kang DR, Hur H, Min BS, Kim NK, Chung HC, et al. Prognostic value of mucinous histology depends on microsatellite instability status in patients with stage III colon cancer treated with adjuvant FOLFOX chemotherapy: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(11):3407–3413. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li P, Xiao Z, Braciak TA, Ou Q, Chen G, Oduncu FS. Systematic immunohistochemical screening for mismatch repair and ERCC1 gene expression from colorectal cancers in China: Clinicopathological characteristics and effects on survival. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0181615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Zeng W, Huang C, Wang J, Yang D, Ma D. Predictive and prognostic implications of mutation profiling and microsatellite instability status in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2018;2018:4585802. doi: 10.1155/2018/4585802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma J, Zhang Y, Shen H, Kapesa L, Liu W, Zeng M, Zeng S. Association between mismatch repair gene and irinotecan-based chemotherapy in metastatic colon cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(12):9599–9609. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3723-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malesci A, Laghi L, Bianchi P, Delconte G, Randolph A, Torri V, Carnaghi C, Doci R, Rosati R, Montorsi M, et al. Reduced likelihood of metastases in patients with microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(13):3831–3839. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohan HM, Ryan E, Balasubramanian I, Kennelly R, Geraghty R, Sclafani F, Fennelly D, McDermott R, Ryan EJ, O'Donoghue D, et al. Microsatellite instability is associated with reduced disease specific survival in stage III colon cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(11):1680–1686. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nopel-Dunnebacke S, Schulmann K, Reinacher-Schick A, Porschen R, Schmiegel W, Tannapfel A, Graeven U. Prognostic value of microsatellite instability and p53 expression in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with oxaliplatin and fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy. Z Gastroenterol. 2014;52(12):1394–1401. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1366781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nordholm-Carstensen A, Krarup PM, Morton D, Harling H. Mismatch repair status and synchronous metastases in colorectal cancer: A nationwide cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(9):2139–2148. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh SY, Kim DY, Kim YB, Suh KW. Oncologic outcomes after adjuvant chemotherapy using FOLFOX in MSI-H sporadic stage III colon cancer. World J Surg. 2013;37(10):2497–2503. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasaki Y, Akasu T, Saito N, Kojima H, Matsuda K, Nakamori S, Komori K, Amagai K, Yamaguchi T, Ohue M, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of extended RAS mutation and mismatch repair status in stage III colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2016;107(7):1006–1012. doi: 10.1111/cas.12950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Thibodeau SN, Marsoni S, Monges G, Labianca R, Kim GP, Yothers G, Allegra C, Moore MJ, et al. DNA mismatch repair status and colon cancer recurrence and survival in clinical trials of 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(11):863–875. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinicrope FA, Mahoney MR, Smyrk TC, Thibodeau SN, Warren RS, Bertagnolli MM, Nelson GD, Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Alberts SR. Prognostic impact of deficient DNA mismatch repair in patients with stage III colon cancer from a randomized trial of FOLFOX-based adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(29):3664–3672. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.48.9591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taieb J, Zaanan A, Le Malicot K, Julie C, Blons H, Mineur L, Bennouna J, Tabernero J, Mini E, Folprecht G, et al. Prognostic Effect of BRAF and KRAS Mutations in Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer Treated With Leucovorin, Fluorouracil, and Oxaliplatin With or Without Cetuximab: A Post Hoc Analysis of the PETACC-8 Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Tan WJ, Hamzah JL, Acharyya S, Foo FJ, Lim KH, Tan IBH, Tang CL, Chew MH. Evaluation of long-term outcomes of microsatellite instability status in an Asian Cohort of Sporadic Colorectal Cancers. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2018;49(3):311–318. doi: 10.1007/s12029-017-9953-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tran B, Kopetz S, Tie J, Gibbs P, Jiang ZQ, Lieu CH, Agarwal A, Maru DM, Sieber O, Desai J. Impact of BRAF mutation and microsatellite instability on the pattern of metastatic spread and prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(20):4623–4632. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watanabe T, Wu TT, Catalano PJ, Ueki T, Satriano R, Haller DG, Benson AB, 3rd, Hamilton SR. Molecular predictors of survival after adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. New Engl J Med. 2001;344(16):1196–1206. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104193441603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westra JL, Schaapveld M, Hollema H, de Boer JP, Kraak MM, de Jong D, ter Elst A, Mulder NH, Buys CH, Hofstra RM, et al. Determination of TP53 mutation is more relevant than microsatellite instability status for the prediction of disease-free survival in adjuvant-treated stage III colon cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5635–5643. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wright CM, Dent OF. Barker M, Newland RC, Chapuis PH, Bokey EL, Young JP, Leggett BA, Jass JR, Macdonald GA. Prognostic significance of extensive microsatellite instability in sporadic clinicopathological stage C colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2000;87(9):1197–1202. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zaanan A, Cuilliere-Dartigues P, Guilloux A, Parc Y, Louvet C, de Gramont A, Tiret E, Dumont S, Gayet B, Validire P, et al. Impact of p53 expression and microsatellite instability on stage III colon cancer disease-free survival in patients treated by 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin with or without oxaliplatin. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zaanan A, Flejou JF, Emile JF, Des GG, Cuilliere-Dartigues P, Malka D, Lecaille C, Validire P, Louvet C, Rougier P, et al. Defective mismatch repair status as a prognostic biomarker of disease-free survival in stage III colon cancer patients treated with adjuvant FOLFOX chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(23):7470–7478. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lanza G, Gafa R, Santini A, Maestri I, Guerzoni L, Cavazzini L. Immunohistochemical test for MLH1 and MSH2 expression predicts clinical outcome in stage II and III colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(15):2359–2367. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, Skora AD, Luber BS, Azad NS, Laheru D, et al. PD-1 Blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. New Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, Lu S, Kemberling H, Wilt C, Luber BS, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357(6349):409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prall F, Dührkop T, Weirich V, Ostwald C, Lenz P, Nizze H, Barten M. Prognostic role of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in stage III colorectal cancer with and without microsatellite instability. Hum Pathol. 2004;35(7):808–816. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pages F, Mlecnik B, Marliot F, Bindea G, Ou FS, Bifulco C, Lugli A, Zlobec I, Rau TT, Berger MD, et al. International validation of the consensus Immunoscore for the classification of colon cancer: a prognostic and accuracy study. Lancet. 2018;391(10135):2128–2139. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30789-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenbaum Matthew W, Bledsoe Jacob R, Morales-Oyarvide Vicente, Huynh Tiffany G, Mino-Kenudson Mari. PD-L1 expression in colorectal cancer is associated with microsatellite instability, BRAF mutation, medullary morphology and cytotoxic tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Modern Pathology. 2016;29(9):1104–1112. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cho SH, Shin MH, Kweon SS, Kim HN, Shim HJ, Hwang JE, Bae WK, Chung IJ. Prognostic role of PD-L1 polymorphism according to MSI in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:15. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee H, Geiersbach K, Ainechi S, Sheehan CE, Jones DM, Affolter K, Bronner MP, Ross JS. Programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) in mismatch repair protein deficient colon cancer: an immunohistochemical and genomic profiling study. Lab Invest. 2016;96:181A. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marginean EC, Melosky B. Is there a role for programmed death ligand-1 testing and immunotherapy in colorectal cancer with microsatellite instability? Part II-The Challenge of Programmed Death Ligand-1 Testing and Its Role in Microsatellite Instability-High Colorectal Cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(1):26–34. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0041-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buckowitz A, Knaebel HP, Benner A, Blaker H, Gebert J, Kienle P, von Knebel Doeberitz M, Kloor M. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer is associated with local lymphocyte infiltration and low frequency of distant metastases. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(9):1746–1753. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kloor M, Becker C, Benner A, Woerner SM, Gebert J, Ferrone S, von Knebel Doeberitz M. Immunoselective pressure and human leukocyte antigen class I antigen machinery defects in microsatellite unstable colorectal cancers. Cancer Res. 2005;65(14):6418–6424. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data were extracted from published articles, and the datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.