Key Points

Question

What is the appropriate interval between treatment and pregnancy among women who receive radioactive iodine treatment after thyroidectomy for thyroid cancer?

Findings

In this population-based cohort study of 111 459 South Korean women of childbearing age (20-49 years) who underwent thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid carcinoma, the receipt of radioactive iodine treatment after surgery was not associated with an increase in the rates of abortion, preterm delivery, or congenital malformation when conception occurred 6 months or more after treatment compared with surgery alone.

Meaning

These large-scale real-world data suggest that radioactive iodine treatment after thyroidectomy is not associated with an increase in adverse pregnancy outcomes when conception occurs after a 6-month waiting period.

Abstract

Importance

Current guidelines recommend that women delay pregnancy for 6 to 12 months after the receipt of radioactive iodine treatment (RAIT) following thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Although concerns exist regarding the risks associated with pregnancy after RAIT, no large-scale study, to date, has investigated the association between RAIT and pregnancy outcomes.

Objective

To investigate whether RAIT was associated with increases in adverse pregnancy outcomes among South Korean women who received RAIT after thyroidectomy for thyroid cancer and to evaluate the appropriate interval between RAIT and conception.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based cohort study used the Health Insurance Review and Assessment database of South Korea to identify a total of 111 459 women of childbearing age (20-49 years) who underwent thyroidectomy for the treatment of differentiated thyroid carcinoma between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2015. Participants were allocated to 2 cohorts: those who underwent surgery alone (n = 59 483 [53.4%]) and those who underwent surgery followed by RAIT (n = 51 976 [46.6%]). The pregnancy outcomes data were collected from January 1, 2008, to December 31, 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The rates of abortion (both spontaneous and induced), preterm delivery, and congenital malformation were assessed. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to control for confounding variables.

Results

Among the 111 459 women of childbearing age who underwent thyroidectomy with or without RAIT for the treatment of thyroid cancer, the mean (SD) age at surgery or RAIT was 39.8 (6.7) years. Of those, 10 842 women (9.7%) became pregnant, and the mean (SD) age at conception was 33.3 (4.4) years. The rates of abortion, preterm delivery, and congenital malformation among patients who underwent surgery alone compared with patients who underwent surgery followed by RAIT were 30.7% vs 32.1% for abortion, 12.8% vs 12.9% for preterm delivery, and 8.9% vs 9.0% for congenital malformation, respectively (P > .05). A subgroup analysis based on the interval between RAIT and conception indicated congenital malformation rates of 13.3% for the interval of 0 to 5 months, 7.9% for 6 to 11 months, 8.3% for 12 to 23 months, and 9.6% for 24 months or more. The adjusted odds ratio of congenital malformation was 1.74 (95% CI, 1.01-2.97; P = .04) in conceptions that occurred 0 to 5 months after RAIT compared with conceptions that occurred 12 to 23 months after RAIT. The abortion rates based on the interval between RAIT and conception were 60.6% for the interval of 0 to 5 months, 30.1% for 6 to 11 months, 27.4% for 12 to 23 months, and 31.9% for 24 months or more.

Conclusions and Relevance

These large-scale real-world data indicate that receipt of RAIT before pregnancy does not appear to be associated with increases in adverse pregnancy outcomes when conception occurs 6 months or more after treatment.

This population-based cohort study uses the Health Insurance Review and Assessment database of South Korea to examine the association between adverse pregnancy outcomes and radioactive iodine treatment after thyroidectomy among South Korean women of childbearing age with thyroid cancer.

Introduction

Radioactive iodine treatment (RAIT) after thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid carcinoma is commonly used for remnant ablation and adjuvant therapy and is intended to improve disease-specific and disease-free survival.1 Radioactive iodine (RAI; sodium iodide I 131, or Na131I) affects ovarian tissue, and common adverse effects of RAIT include oligomenorrhea, temporary secondary amenorrhea, and/or an earlier onset of menopause.2,3,4 Radiation exposure is also a risk factor for mutagenic abnormalities.

In 2015, the American Thyroid Association released guidelines that strongly recommended women of childbearing age who are scheduled to receive RAIT should have a negative screening result for pregnancy before RAI administration and should avoid pregnancy for 6 to 12 months after receiving RAIT.1 In its 2017 guidelines, the American Thyroid Association updated its recommendation for deferring pregnancy, reducing the interval to 6 months after RAIT; however, the quality of the evidence supporting this recommendation remains relatively low.5 Guidelines from the European Association of Nuclear Medicine Therapy Committee recommend that pregnancy should be avoided and effective contraception should be used for 6 to 12 months after receiving RAIT.6

A study from 20152 reported that RAIT is associated with a substantial delay in the median time between treatment and first live birth across most reproductive age groups and with a significantly decreased birth rate among women of advanced maternal age (35-39 years). Although concerns exist regarding the risks associated with pregnancy after RAIT, no large-scale study, to our knowledge, has investigated the association between RAIT and pregnancy outcomes.

This study used the Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) database of South Korea to investigate whether RAIT was associated with an increase in adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as spontaneous and induced abortions, preterm deliveries, and congenital malformations, among South Korean women of childbearing age (20-49 years) and to evaluate the appropriate interval between the receipt of RAIT and conception.

Methods

Data for this study were collected using the HIRA database of South Korea, which includes the health insurance claims of the country’s entire population. The HIRA database includes patient demographics, records of diagnoses as determined by the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), procedure codes, and prescription records. Identifying data were removed from the HIRA patient records in accordance with South Korea’s Personal Information Protection Act, which is maintained by public agencies. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki7 and approved by the institutional review board of the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service of South Korea with a waiver of informed consent.

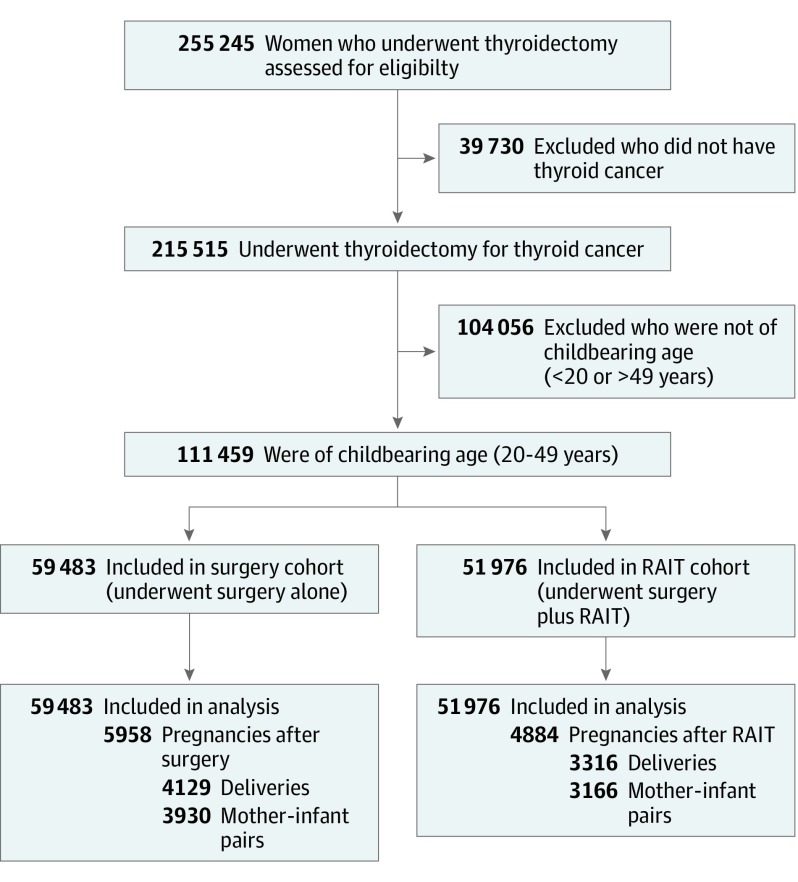

The database search identified 255 245 women who underwent thyroidectomy (HIRA procedure codes P4561, P4552, P4554, P4551, and P4553) between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2015. This sample was narrowed to 215 515 women who underwent thyroidectomy for the treatment of a thyroid malignancy (ICD-10 code C73); of those, 111 459 women of childbearing age (20-49 years) were selected for inclusion in the study. The HIRA prescription claims code 3684 was used to identify women who received RAIT, which was defined as the administration of an RAI dose greater than 0.925 GBq. The study population was then allocated to 2 groups: a surgery cohort composed of women who underwent thyroidectomy alone (n = 59 483 [53.4%]) and a RAIT cohort composed of women who underwent thyroidectomy followed by RAIT (n = 51 976 [46.6%]). Women who conceived before December 31, 2016, were included. A total of 10 842 pregnancies, with 5958 in the surgery cohort and 4884 in the RAIT cohort, occurred during the study period. The linked records of infants delivered were also obtained from the HIRA database. Of the 7445 deliveries in both cohorts, 7096 records were matched as mother-infant pairs, accounting for 95.3% of all deliveries within the study period (Figure).

Figure. Flow Diagram of Study Cohort Selection.

RAIT indicates radioactive iodine treatment.

The date of conception was defined as the earliest of 38 weeks (266 days) before the date of delivery (HIRA procedure codes R3131-R3148, R4351-R4362, R4380, R4501-R4520, R5001-R5002, RA311-RA318, and RA361-RA362), 14 days before a clinic visit with an ICD-10 code for abortion (ICD-10 codes O00-O08), or 14 days before a clinic visit with an ICD-10 code for pregnancy (ICD-10 codes Z321 and Z33-Z35), in which only patients who had revisited the clinic within 90 days with an ICD-10 code for pregnancy were enrolled. Data were further analyzed based on the cumulative RAI dose and the interval between RAIT and conception; intervals were categorized as 0 to 5 months (0-179 days), 6 to 11 months (180-359 days), 12 to 23 months (360-719 days), and 24 months or more (≥720 days). The conception interval after treatment was calculated from the date of thyroidectomy in the surgery cohort and from the date of RAI administration in the RAIT cohort. Among patients who received RAIT more than once, the conception interval was calculated from the date of the last RAIT before pregnancy.

We analyzed both spontaneous and induced abortions (defined as conception without delivery within 280 days), preterm deliveries (ICD-10 codes O60, O601, and O603 at 0-90 days before delivery), and the presence of congenital malformations at birth or during the first year of life. All congenital malformations were categorized into 10 groups that were identified using ICD-10 codes: nervous system (ICD-10 codes Q00-Q07); eye, ear, face, and neck (ICD-10 codes Q10-Q18); circulatory system (ICD-10 codes Q20-Q28); respiratory system (ICD-10 codes Q30-Q34); cleft lip and cleft palate (ICD-10 codes Q35-Q37); other digestive system (ICD-10 codes Q38-Q45); genital organs (ICD-10 codes Q50-Q56); urinary system (ICD-10 codes Q60-Q64); musculoskeletal system (ICD-10 codes Q65-Q79); and other congenital malformations (ICD-10 codes Q80-Q99). Congenital stenosis and stricture of lacrimal duct (ICD-10 code Q10.5) and ankyloglossia (ICD-10 code Q38.1) were excluded from analysis because clinical diagnosis of these conditions is inconsistent, and the conditions are often resolved without medical treatment. The pregnancy outcomes data were collected from January 1, 2008, to December 31, 2017.

Descriptive statistical analyses were performed for all women included in the study. A χ2 test was used to evaluate the associations between pregnancy outcomes and RAIT. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to calculate adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% CIs for risk factors associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes among women who received RAIT. All statistical tests were 2-sided with a significance threshold of P < .05. Data analyses were performed using R software, version 3.4.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Analysis).

Results

Among the 111 459 women who underwent thyroidectomy for the treatment of thyroid cancer, the mean (SD) age at treatment with surgery or RAIT was 39.8 (6.7) years (Table 1). Of those, 10 842 women (9.7%) became pregnant (10.0% of women in the surgery cohort compared with 9.4% of women in the RAIT cohort; P < .001), and the mean (SD) age at conception for both cohorts was 33.3 (4.4) years. In the RAIT cohort, the mean (SD) cumulative RAI dose was 4.44 (3.17) GBq; 10 367 patients (19.9%) received RAIT more than 2 times. Significant differences were noted in the time between treatment and conception in the surgery and RAIT cohorts (mean [SD], 22.0 [19.1] months vs 25.3 [17.4] months, respectively; P < .001). The conception rates in the RAIT cohort were significantly lower than those of the surgery cohort for the intervals of 0 to 5 months and 6 to 11 months after treatment (0.7% vs 2.0% and 1.4% vs 1.9%, respectively; P < .001). The conception rates in the 12- to 23-month interval were 3.5% in the RAIT cohort and 2.6% in the surgery cohort.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population (N = 111 459) | Surgery Cohort (n = 59 483) | RAIT Cohort (n = 51 976) | ||

| Age at thyroidectomy or RAIT, mean (SD), y | 39.8 (6.7) | 39.8 (6.6) | 39.8 (6.9) | .70 |

| Pregnancies | 10 842 (9.7) | 5958 (10.0) | 4884 (9.4) | <.001 |

| Age at thyroidectomy, mean (SD), y | 31.2 (4.5) | 31.5 (4.4) | 30.7 (4.5) | <.001 |

| Age at RAIT, mean (SD), y | NA | NA | 31.2 (4.5) | NA |

| Age at conception, y | .39 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 33.3 (4.4) | 33.3 (4.3) | 33.2 (4.4) | |

| 20-29 | 2003 (18.5) | 1078 (18.1) | 925 (18.9) | .25 |

| 30-34 | 5063 (46.7) | 2801 (47.0) | 2262 (46.3) | |

| 35-39 | 2810 (25.9) | 1525 (25.6) | 1285 (26.3) | |

| ≥40 | 966 (8.9) | 554 (9.3) | 412 (8.4) | |

| Conception interval, mo | <.001 | |||

| 0-5 | 1545 (1.4) | 1187 (2.0) | 358 (0.7) | |

| 6-11 | 1860 (1.7) | 1150 (1.9) | 710 (1.4) | |

| 12-23 | 3378 (3.0) | 1559 (2.6) | 1819 (3.5) | |

| ≥24 | 4059 (3.6) | 2062 (3.5) | 1997 (3.8) | |

| Deliveries, No. (% of pregnancies) | 7445 (68.7) | 4129 (69.3) | 3316 (67.9) | .12 |

| Mother-infant pairs | 7096 | 3930 | 3166 | .59 |

| Infant status | .33 | |||

| Male, single birth | 3510 (49.5) | 1914 (48.7) | 1596 (50.4) | |

| Female, single birth | 3416 (48.1) | 1923 (48.9) | 1493 (47.2) | |

| Multiple birth | 170 (2.4) | 93 (2.4) | 77 (2.4) | |

Abbreviation: RAIT, radioactive iodine treatment.

No statistically significant differences were observed in the rates of abortion (both spontaneous and induced) between the surgery and RAIT cohorts (30.7% vs 32.1%, respectively; P = .12; Table 2). A total of 956 preterm deliveries (12.8%) were observed in both cohorts, with no significant difference between the surgery and RAIT cohorts (12.8% vs 12.9%, respectively; P = .96). In total, 634 cases of congenital malformation (8.9%) were observed in both cohorts, with 349 cases (8.9%) in the surgery cohort and 285 cases (9.0%) in the RAIT cohort (P = .89).

Table 2. Frequency of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes.

| Outcome | No. (%) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population (N = 111 459) | Surgery Cohort (n = 59 483) | RAIT Cohort (n = 51 976) | ||

| Pregnancies | 10 842 (9.7) | 5958 (10.0) | 4884 (9.4) | <.001 |

| Abortions, No. (% of pregnancies) | 3397 (31.3) | 1829 (30.7) | 1568 (32.1) | .12 |

| Preterm deliveries, No. (% of deliveries) | 956 (12.8) | 529 (12.8) | 427 (12.9) | .96 |

| Deliveries, No. (% of pregnancies) | 7445 (68.7) | 4129 (69.3) | 3316 (67.9) | .12 |

| Mother-infant pairs | 7096 | 3930 | 3166 | |

| Congenital malformations, No. (% of mother-infant pairs) | 634 (8.9) | 349 (8.9) | 285 (9.0) | .89 |

| Nervous system | 22 (0.3) | 9 (0.2) | 13 (0.4) | NA |

| Eye, ear, face and neck | 31 (0.4) | 14 (0.4) | 17 (0.5) | |

| Circulatory system | 225 (3.2) | 124 (3.2) | 101 (3.2) | |

| Respiratory system | 18 (0.3) | 13 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) | |

| Cleft lip and cleft palate | 12 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) | |

| Other digestive system | 27 (0.4) | 13 (0.3) | 14 (0.4) | |

| Genital organs | 46 (0.6) | 20 (0.5) | 26 (0.8) | |

| Urinary system | 61 (0.9) | 36 (0.9) | 25 (0.8) | |

| Musculoskeletal system | 198 (2.8) | 110 (2.8) | 88 (2.8) | |

| Other malformation | 45 (0.6) | 25 (0.6) | 20 (0.6) | |

Abbreviation: RAIT, radioactive iodine treatment.

In a preplanned subgroup analysis based on the interval between RAIT and conception, 18 cases of congenital malformation (13.3%) were observed in the 0- to 5-month interval, 37 cases (7.9%) in the 6- to 11-month interval, 105 cases (8.3%) in the 12- to 23-month interval, and 125 cases (9.6%) in the 24-month or more interval (Table 3). Eighteen cases of congenital malformation were observed among women who became pregnant less than 6 months after RAIT, including 6 cases of malformation in the circulatory system, 4 in the musculoskeletal system, and 3 in the urinary system, with rare cases of malformation in the nervous system, respiratory system, lip and palate, and genital organs. The OR of congenital malformation after adjusting for age at conception and cumulative RAI dose was 1.74 (95% CI, 1.01-2.97; P = .04) for the 0- to 5-month interval after RAIT compared with the 12- to 23-month interval after RAIT (Table 4). In the surgery cohort, the interval between surgery and conception was not associated with a risk of congenital malformation.

Table 3. Pregnancy Outcomes Based on Conception Interval After Surgery or RAIT and Cumulative RAI Dose.

| Pregnancy Outcome | Surgery Cohort, No. (%) | RAIT Cohort, No. (%) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conception Interval After Surgery, mo | Conception Interval After RAIT, mo | Cumulative RAI Dose, GBq | ||||||||||||

| 0-5 | 6-11 | 12-23 | ≥24 | P Value | 0-5 | 6-11 | 12-23 | ≥24 | P Value | ≤1.11 (n = 10 315) | 1.12-3.7 (n = 16 477) | ≥3.8 (n = 25 184) | P Value | |

| Pregnancies | 1187 | 1150 | 1559 | 2062 | NA | 358 | 710 | 1819 | 1997 | NA | 807 | 1325 | 2752 | NA |

| Abortions, No. (% of pregnancies) | 355 (29.9) | 345 (30.0) | 468 (30.0) | 661 (32.1) | .43 | 217 (60.6) | 214 (30.1) | 499 (27.4) | 638 (31.9) | <.001 | 260 (32.2) | 443 (33.4) | 865 (31.4) | .44 |

| Preterm deliveries, No. (% of deliveries) | 79 (9.5) | 93 (11.6) | 133 (12.2) | 224 (16.0) | <.001 | 15 (10.6) | 61 (12.3) | 149 (11.3) | 202(14.9) | .04 | 82 (15.0) | 107 (12.1) | 238 (12.6) | .26 |

| Deliveries | 832 (70.1) | 805 (70.0) | 1091 (70.0) | 1401 (67.9) | .43 | 141 (39.4) | 496 (69.9) | 1320 (72.6) | 1359 (68.1) | <.001 | 547 (67.8) | 882 (66.6) | 1887 (68.6) | .44 |

| Mother-infant pairs | 792 | 762 | 1030 | 1346 | .23 | 135 | 471 | 1264 | 1296 | .89 | 525 | 846 | 1795 | .53 |

| Congenital malformations, No. (% of mother-infant pairs) | 67 (8.5) | 58 (7.6) | 103 (10.0) | 121 (9.0) | .35 | 18 (13.3) | 37 (7.9) | 105 (8.3) | 125 (9.6) | .16 | 45 (8.6) | 76 (9.0) | 164 (9.1) | .92 |

| Nervous system | 2 (0.3) | 0 | 4 (0.4) | 3 (0.2) | NA | 1 (0.7) | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.2) | 7 (0.5) | NA | 5 (1.0) | 0 | 8 (0.4) | NA |

| Eye, ear, face and neck | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.3) | 0 | 5 (1.1) | 7 (0.6) | 5 (0.4) | 7 (1.3) | 1 (0.1) | 9 (0.5) | |||

| Circulatory system | 23 (2.9) | 18 (2.4) | 40 (3.9) | 43 (3.2) | 6 (4.4) | 12 (2.5) | 40 (3.2) | 43 (3.3) | 14 (2.7) | 32 (3.8) | 55 (3.1) | |||

| Respiratory system | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 5 (0.5) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | |||

| Cleft lip and cleft palate | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.2) | |||

| Other digestive system | 6 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 0 | 3 (0.6) | 4 (0.3) | 7 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) | 10 (0.6) | |||

| Genital organs | 2 (0.3) | 6 (0.8) | 6 (0.6) | 6 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (0.6) | 10 (0.8) | 12 (0.9) | 3 (0.6) | 6 (0.7) | 17 (0.9) | |||

| Urinary system | 6 (0.8) | 5 (0.7) | 11 (1.1) | 14 (1.0) | 3 (2.2) | 2 (0 .4) | 5 (0.4) | 15 (1.2) | 5 (1.0) | 5 (0.6) | 15 (0.8) | |||

| Musculoskeletal system | 20 (2.5) | 20 (2.6) | 27 (2.6) | 43 (3.2) | 4 (3.0) | 13 (2.8) | 36 (2.8) | 35 (2.7) | 14 (2.7) | 25 (3.0) | 49 (2.7) | |||

| Other malformation | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 5 (0.5) | 14 (1.0) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (0.6) | 6 (0.5) | 9 (0.7) | 2 (0.4) | 4 (0.5) | 14 (0.8) | |||

Abbreviations: RAI, radioactive iodine (sodium iodide I 131, or Na131I); RAIT, radioactive iodine treatment.

Table 4. Multivariate Analysis of Risk Factors Associated With Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Women Receiving RAIT.

| Risk Factor | Abortion | Preterm Delivery | Congenital Malformation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Cumulative RAI dose, GBq | ||||||

| ≤1.11 [Reference] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 1.12-3.7 | 1.11 (0.91-1.36) | .30 | 0.79 (0.58-1.08) | .14 | 1.06 (0.72-1.56) | .76 |

| ≥3.8 | 1.02 (0.85-1.22) | .81 | 0.82 (0.63-1.08) | .16 | 1.08 (0.76-1.52) | .68 |

| Conception interval after RAIT, mo | ||||||

| 0-5 | 4.08 (3.19-5.22) | <.001 | 0.92 (0.53-1.62) | .78 | 1.74 (1.01-2.97) | .04 |

| 6-11 | 1.16 (0.95-1.42) | .14 | 1.10 (0.80-1.51) | .57 | 0.95 (0.64-1.41) | .80 |

| 12-23 [Reference] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| ≥24 | 1.08 (0.93-1.25) | .31 | 1.34 (1.07-1.69) | .01 | 1.17 (0.89-1.54) | .26 |

| Age at conception, y | ||||||

| 20-29 [Reference] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 30-34 | 1.17 (0.97-1.40) | .10 | 0.97 (0.74-1.27) | .83 | 1.27 (0.91-1.76) | .16 |

| 35-39 | 2.11 (1.73-2.56) | <.001 | 1.22 (0.90-1.64) | .20 | 1.28 (0.88-1.86) | .19 |

| ≥40 | 10.61 (8.05-13.96) | <.001 | 1.22 (0.68-2.17) | .51 | 1.39 (0.60-3.22) | .44 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; RAI, radioactive iodine (sodium iodide I 131, or Na131I); RAIT, radioactive iodine treatment.

The rates of abortion (both spontaneous and induced) based on the interval between RAIT and conception in the RAIT cohort were 60.6% for the 0- to 5-month interval, 30.1% for the 6- to 11-month interval, 27.4% for the 12- to 23-month interval, and 31.9% for the 24-month or more interval. Early conception (less than 6 months) after RAIT was associated with an increased abortion rate (AOR, 4.08; 95% CI, 3.19-5.22; P < .001). The abortion rate for the 6- to 11-month interval between RAIT and conception did not differ significantly from that of the 12- to 23-month interval (AOR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.95-1.42; P = .14). Increased maternal age (40 years or older) at conception was associated with an increased risk of abortion (AOR, 10.61; 95% CI, 8.05-13.96; P < .001). The number of preterm births in the surgery cohort was 79 (9.5%) in the 0- to 5-month interval, 93 (11.6%) in the 6- to 11-month interval, 133 (12.2%) in the 12- to 23-month interval, and 224 (16.0%) in the 24-month or more interval (P < .001). In the RAIT cohort, the number of preterm births was 15 (10.6%) for the 0- to 5-month interval, 61 (12.3%) for the 6- to 11-month interval, 149 (11.3%) for the 12- to 23-month interval, and 202 (14.9%) for the 24-month or more interval (P = .04). The cumulative dose of RAI was not associated with the risk of congenital malformation.

Discussion

In this population-based cohort study, the rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including spontaneous and induced abortions, preterm deliveries, and congenital malformations, did not differ between the surgery and RAIT cohorts. However, a subgroup analysis that examined the interval between RAIT and conception found that, after adjusting for age at conception and cumulative RAI dose, the congenital malformation rate was higher when conception occurred early (less than 6 months) after RAIT. Early conception after RAIT was also associated with an increased abortion rate; however, this association was not observed in the 6- to 11-month interval group. Adverse pregnancy outcomes were not associated with the cumulative RAI dose.

The oncologic complications of RAIT associated with an increased risk of developing solid cancers and leukemia have been relatively well documented in studies of large populations.8,9,10,11,12 Small studies have reported the pregnancy outcomes of women who received RAIT before conception.13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 To our knowledge, this study is the first large-scale, nationwide cohort study to examine the associations between RAIT and pregnancy outcomes.

Previous studies that examined congenital malformation rates among women who received RAIT before conception did not report any significant associations; however, these studies were limited owing to the small number of patients who had received RAIT and the rarity of congenital malformations.19,20 Those data could therefore not be stratified based on the cumulative RAI dose and the interval between RAIT and conception. After RAI administration, the primary sources of radiation to the ovaries are the blood, bladder, and gut, along with iodine uptake in metastases close to the ovaries.16 Although a radiation dose of 140 mGy has been reported to be damaging to the ovaries, when an RAI dose of 3.7 GBq was administered,20 the specific dose absorbed in the ovaries after RAIT was only weakly associated with the RAI dose administered owing to multiple anatomic, physiologic, and pathophysiologic factors.19 Furthermore, the patient’s hypothyroid status at the time of RAI administration can affect the renal clearance of iodine, thereby increasing radiation exposure to the ovaries. In this study, even groups that received a cumulative RAI dose of more than 3.7 GBq did not exhibit increased congenital malformations, although conception less than 6 months after RAIT was associated with an increased risk of congenital malformation. The possibility that a substantial percentage of the induced abortions among early conceptions may have masked an increased incidence of congenital malformation remains to be evaluated. However, based on these real-world observational data, a waiting period after RAIT, as current clinical practice guidelines recommend, appears to be a reasonable approach.

Substantial differences were observed in preterm births based on the interval between RAIT and conception; however, the frequency of preterm births was higher in those who became pregnant years after RAIT compared with those who became pregnant within the first few months. In the surgery cohort, the preterm birth rates after surgery also increased over time. Considering these data, preterm birth rates do not appear to be associated with RAIT.

The increase in abortion rates among patients who conceived early after RAIT is consistent with a previous systematic review, which reported that the rates of spontaneous and induced abortion increased in the first year after RAIT.3 Our study was able to further categorize the interval between RAIT and conception into 6-month periods owing to its large sample. The results indicated that the abortion rate in the RAIT cohort was higher among women who became pregnant less than 6 months after RAIT compared with those who became pregnant 6 months or more after RAIT. However, among conceptions that occurred 6 to 11 months after RAIT, we did not observe a statistically higher rate of abortion compared with conceptions that occurred 12 to 23 months after RAIT. In the surgery cohort, no difference was observed in the abortion rate relative to the interval between surgery and conception.

Although this study was not able to differentiate between spontaneous and induced abortions owing to limitations in the HIRA claims database, a high rate of induced abortions may have been likely during the early conception stage after RAIT. The induced abortion rate among patients who received RAIT has been reported in previous studies.16,17 A study by Chow et al17 noted that 8 of 15 patients (53.3%) chose to terminate a pregnancy if conception occurred within 1 year after RAIT. Schlumberger et al16 also reported a significant increase in induced abortions among women who received RAIT the year before conception (10 of 20 [50%]) compared with those who did not (45 of 247 [18%]; P < .001). Given that current guidelines advise women to defer pregnancy for 6 to 12 months after RAIT, women who became pregnant early after RAIT may have feared adverse effects on their fetuses or may have been advised by their physicians to undergo a therapeutic abortion. Thousands of induced abortions were reported after the Chernobyl accident.22,23 Nevertheless, in real-world practice, spontaneous and induced abortion rates did not continue to increase beyond 6 months after RAIT.

Although current guidelines recommend that women delay pregnancy for 6 to 12 months after RAIT,1,5,6 in clinical practice, many clinicians may recommend extending the waiting period to 12 months. A previous study reported that the median time to first birth was 34.5 months among women who received RAIT compared with 26.1 months among women who did not.2 Our data also demonstrated that the RAIT cohort experienced a longer interval between RAIT and conception compared with the surgery cohort. This finding is likely to be an example of delayed childbearing behavior among women who received RAIT; however, the possibility that women experienced increased infertility within the first 6 months after RAIT cannot be excluded. In either case, given the increased obstetric and perinatal complications associated with delayed pregnancy owing to increased maternal age,24,25,26 accurate information about the recommended interval between RAIT and conception is critical for women of childbearing age and their treating physicians.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Disease diagnoses may have been miscoded in the claims data. Our findings were based on ICD-10 diagnosis codes, and these codes are primarily intended to be used for reimbursement purposes. Despite any potential misclassifications, ICD-10 codes are a critical tool for large-scale population studies. This study used operational definitions to identify the date of conception because the HIRA claims data did not provide detailed information about exact gestational age at birth. Therefore, for the start date of pregnancy, we used 38 weeks (266 days) before delivery, which is the typical duration of a full-term human pregnancy, as noted in previous studies.27,28 However, if a delivery was notably preterm, the start date of pregnancy may have been set at a date before actual conception because our start date was assumed to be 38 weeks before delivery. In this case, the calculated interval between RAIT and conception would have been shorter than the actual interval, which may have resulted in overestimation of preterm birth rates in the 0- to 5-month interval. However, even if some of these values were overestimated, the association between a higher frequency of preterm births among those who became pregnant years after RAIT compared with those who became pregnant less than 6 months after RAIT would remain. On the other hand, in cases of conception without delivery, in which the start date of pregnancy was assumed to be 14 days before the first clinic visit, the calculated conception date may have been set later than actual conception date. In this case, abortions in the 0- to 5-month interval would have been underestimated because the calculated interval may have been longer than the actual interval.

Factors other than RAIT history, including stage of maternal thyroid cancer, history of smoking, alcohol intake, preexisting ovarian dysfunction, and partner’s genetic disease, which may have influenced the results, were not considered. Patients who received RAIT were given maintenance treatment with suppressive levothyroxine therapy, even during pregnancy, and suppression of thyrotropin levels may have affected the study’s results. Furthermore, we were not able to assess maternal hypothyroidism caused by medication noncompliance or inadequately titrated thyroid hormone replacement therapy owing to the absence of data about maternal thyroid function. Previous data have consistently indicated that maternal thyroid hormone status is associated with pregnancy complications and adverse effects in fetuses and infants.20,29 This study included a surgery cohort that received maintenance treatment with suppressive levothyroxine therapy without RAIT, but the possibility that abnormal thyroid hormone status affected the study’s results cannot be excluded. We did not examine studies of radiographic imaging, such as pelvic computed tomography or diagnostic radioiodine scans. Although the effects of radiographic imaging examined in these studies may have affected our results, the number of imaging studies conducted among pregnant women is low; therefore, their influence was considered to be minimal to the study’s results.

Conclusions

These large-scale real-world data suggest that RAIT after thyroidectomy is not associated with an increase in adverse pregnancy outcomes when conception occurs 6 months or more after treatment compared with thyroidectomy alone.

References

- 1.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1-133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu JX, Young S, Ro K, et al. Reproductive outcomes and nononcologic complications after radioactive iodine ablation for well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2015;25(1):133-138. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawka AM, Lakra DC, Lea J, et al. A systematic review examining the effects of therapeutic radioactive iodine on ovarian function and future pregnancy in female thyroid cancer survivors. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008;69(3):479-490. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03222.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawka AM, Lea J, Alshehri B, et al. A systematic review of the gonadal effects of therapeutic radioactive iodine in male thyroid cancer survivors. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008;68(4):610-617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03081.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, et al. 2017 guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and the postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27(3):315-389. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luster M, Clarke SE, Dietlein M, et al. ; European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) . Guidelines for radioiodine therapy of differentiated thyroid cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35(10):1941-1959. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0883-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seo GH, Cho YY, Chung JH, Kim SW. Increased risk of leukemia after radioactive iodine therapy in patients with thyroid cancer: a nationwide, population-based study in Korea. Thyroid. 2015;25(8):927-934. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molenaar RJ, Sidana S, Radivoyevitch T, et al. Risk of hematologic malignancies after radioiodine treatment of well-differentiated thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(18):1831-1839. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.0232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubino C, de Vathaire F, Dottorini ME, et al. Second primary malignancies in thyroid cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(9):1638-1644. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subramanian S, Goldstein DP, Parlea L, et al. Second primary malignancy risk in thyroid cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2007;17(12):1277-1288. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sawka AM, Thabane L, Parlea L, et al. Second primary malignancy risk after radioactive iodine treatment for thyroid cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2009;19(5):451-457. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vini L, Hyer S, Al-Saadi A, Pratt B, Harmer C. Prognosis for fertility and ovarian function after treatment with radioiodine for thyroid cancer. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78(916):92-93. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.916.92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.do Rosario PW, Barroso AL, Rezende LL, Padrao EL, Borges MA, Purisch S. Malformations in the offspring of women with thyroid cancer treated with radioiodine for the ablation of thyroid remnants. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2006;50(5):930-933. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27302006000500016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dottorini ME, Lomuscio G, Mazzucchelli L, Vignati A, Colombo L. Assessment of female fertility and carcinogenesis after iodine-131 therapy for differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 1995;36(1):21-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlumberger M, De Vathaire F, Ceccarelli C, et al. Exposure to radioactive iodine-131 for scintigraphy or therapy does not preclude pregnancy in thyroid cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 1996;37(4):606-612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow SM, Yau S, Lee SH, Leung WM, Law SC. Pregnancy outcome after diagnosis of differentiated thyroid carcinoma: no deleterious effect after radioactive iodine treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(4):992-1000. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandao CD, Miranda AE, Correa ND, Sieiro Netto L, Corbo R, Vaisman M. Radioiodine therapy and subsequent pregnancy. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;51(4):534-540. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27302007000400006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bal C, Kumar A, Tripathi M, et al. High-dose radioiodine treatment for differentiated thyroid carcinoma is not associated with change in female fertility or any genetic risk to the offspring. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(2):449-455. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.02.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garsi JP, Schlumberger M, Rubino C, et al. Therapeutic administration of 131I for differentiated thyroid cancer: radiation dose to ovaries and outcome of pregnancies. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(5):845-852. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.046599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casara D, Rubello D, Saladini G, et al. Pregnancy after high therapeutic doses of iodine-131 in differentiated thyroid cancer: potential risks and recommendations. Eur J Nucl Med. 1993;20(3):192-194. doi: 10.1007/BF00169997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castronovo FP., Jr Teratogen update: radiation and Chernobyl. Teratology. 1999;60(2):100-106. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferretti PP, Restori E, Algeri TM, Dall’Ara P, Borasi G. Radiation exposure of the embryo and the fetus: real risks or unjustified fears? Radiol Med. 1989;77(5):544-548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frederiksen LE, Ernst A, Brix N, et al. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes at advanced maternal age. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(3):457-463. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balasch J, Gratacos E. Delayed childbearing: effects on fertility and the outcome of pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;24(3):187-193. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3283517908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson JA, Tough S; SOGC Genetics Committee . Delayed child-bearing. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34(1):80-93. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35138-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seo GH, Kim TH, Chung JH. Antithyroid drugs and congenital malformations: a nationwide Korean cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(6):405-413. doi: 10.7326/M17-1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park KY, Kwon HJ, Wie JH, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in patients with vitiligo: a nationwide population-based cohort study from Korea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(5):836-842. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LaFranchi SH, Haddow JE, Hollowell JG. Is thyroid inadequacy during gestation a risk factor for adverse pregnancy and developmental outcomes? Thyroid. 2005;15(1):60-71. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]