Abstract

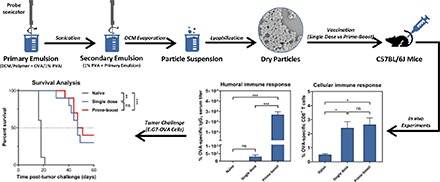

Many factors affect vaccine efficacy. One of the most salient is the frequency and intervals of vaccine administration. In this study, we assessed the vaccine administration modality for a recently reported polyanhydride-based vaccine formulation, shown to generate antitumor activity. Polyanhydride particles encapsulating ovalbumin (OVA) were prepared using a double-emulsion technique and subcutaneously delivered to mice either as a single-dose or as prime-boost vaccine regimens in which two different time intervals between prime and boost were assessed (7 or 21 days). This was followed by measurement of cellular and humoral immune responses, and subsequent challenge of the mice with a lethal dose of E.G7-OVA cells to evaluate tumor protection. Interestingly, a single dose of the polyanhydride particle-based formulation induced sustained OVA-specific cellular immune responses just as effectively as the prime-boost regimens. In addition, mice receiving single-dose vaccine had similar levels of protection against tumor challenge compared with mice administered prime-boosts. In contrast, measurements of OVA-specific IgG antibody titers indicated that a booster dose was required to stimulate strong humoral immune responses, since it was observed that mice administered a prime-boost vaccine had significantly higher OVA-specific IgG1 serum titers than mice administered a single dose. These findings indicate that the requirement for a booster dose using these particles appears unnecessary for the generation of effective cellular immunity.

Introduction

Despite recent biotechnological and therapeutic advances, cancer continues to be a challenging health problem (Garcia-Cremades et al., 2017; Siegel et al., 2017; Gómez de Cedrón et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). With many cancer types being refractory to conventional chemotherapy and with the complication that chemotherapeutics are often limited in their efficacy owing to a steep dose-response relationship and narrow therapeutic window (Paci et al., 2014; Alfarouk et al., 2015), alternative, or at least adjuvant, therapeutic strategies are required. An alternative approach that has demonstrated considerable promise in preclinical studies is the use of cancer vaccines capable of generating tumor-specific adaptive immune responses (Andersen et al., 2006; Martínez-Lostao et al., 2015). Adaptive immune responses can be delineated as humoral (antibody-mediated) or cellular [involving CD8+ T lymphocytes; often referred to as cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs)]. Of these two types of responses, cellular immunity is considered the more important in the context of affecting antitumor potency, particularly for tumor antigens that are not expressed on the tumor cell surface in their native form. Thus, generating tumor-specific CTLs has been the primary focus of clinical oncoimmunologists owing to the ability of CTLs to target tumor antigens regardless of where the antigens are localized upon expression (Maher and Davies, 2004; Zhou et al., 2016). Specifically, it is probable that tumor-antigen-specific humoral immune responses are only effective against tumors that express native tumor antigens on the tumor cell surface, whereas CTLs can target all tumor antigens expressed by tumors as long as the tumor cells express major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and that the relevant epitope is appropriately processed and presented (Colombo et al., 2000; Andersen et al., 2006; Reuschenbach et al., 2009; Blum et al., 2013).

For successful vaccination, vaccine efficacy and safety are important aspects (Lahariya, 2016). Factors affecting vaccine efficacy, potency, and duration of immunity are manifold. These factors can be generally classified into three groups: 1) vaccinee (host) factors such as age, gender, and presence of comorbidity, 2) vaccine design/formulation parameters, including composition (+/− adjuvant), and chemical and physical properties, and 3) vaccine delivery regimens, such as mode of delivery, dose, and frequency (Zhang et al., 2015). Variable parameters of vaccine delivery regimens, such as the number and timing of vaccine doses, are critically important factors to be considered to achieve optimal vaccine efficacy. Although a single dose of a certain vaccine formulation may confer an enduring immunity, a single dose of a different vaccine formulation may provide protection for only a short duration and therefore may require additional dose(s) (boosters) to enhance immunopotency for longer periods (Siegrist, 2013). This may be attributable, at least partially, to the fact that different vaccine delivery vehicles can differ significantly from periods of days to months in their release profiles of their antigenic cargo (Jain et al., 2005). In this regard, sustained-release formulations can provide prolonged immunostimulation and induce long-lasting immune responses (Irvine et al., 2013). Since there is limited data adequately documenting the association between specific particle-based cancer vaccine regimens and the resultant qualitative and quantitative antitumor immune responses (i.e., frequencies of antigen-specific CTLs), this work focused on assessing the administration modality of a relatively new particle-based cancer vaccine formulation.

Compared with soluble antigen delivery, particulate antigen delivery platforms targeting antigen-presenting cells have a dramatic effect on immunogenicity as shown in preclinical studies (Joshi et al., 2013; Ahmed et al., 2014; Geary et al., 2015; de Barros et al., 2017; Fontana et al., 2017). In this study, ovalbumin (OVA), a model tumor antigen, was loaded into a particle-based vaccine formulation and delivered subcutaneously either as a single dose or as prime-boost vaccine regimens with distinct time intervals. The main objective of our current study was to assess the immune potency of these different vaccine administration regimes by using a recently reported polyanhydride-based cancer vaccine formulation (Wafa et al., 2017). Formulations derived from polyanhydride polymers have shown promise as biocompatible and biodegradable polymers (Roy et al., 2016) and have been used in marketed controlled-release medical products such as Gliadel (polyanhydride-based wafer containing carmustine for treating glioblastoma multiforme) and Septacin (polyanhydride-based beads loaded with gentamycin for treating osteomyelitis) (Li et al., 2002; Jain et al., 2005; Perry et al., 2007). In addition, polyanhydride particles have been reported to possess immunostimulatory properties that trigger Toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated signaling in dendritic cells (DCs) (Tamayo et al., 2010). Here, our goal was to determine the effects on antigen-specific immune responses and tumor growth of variations in the prime-boost regimen of an antigen-loaded polyanhydride particle formulation.

Materials and Methods

Particle Preparation and Characterization

Preparation of Empty, OVA-, and Coumarin-Loaded Polyanhydride Particles.

Monomers of 1,8-bis(p-carboxyphenoxy)-3,6-dioxaoctane (CPTEG) and 1,6-bis(p-carboxyphenoxy) hexane (CPH) were copolymerized in a 20:80 M ratio (Fig. 1) via melt polycondensation, as previously described (Wafa et al., 2017). The purity, composition, and molecular weight of the polymer were verified with 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (Varian VXR-300 MHz; Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA) and found to be consistent with previous publications (Torres et al., 2007; Wafa et al., 2017). Polyanhydride particles encapsulating OVA were prepared using a water-in-oil-in-water double-emulsion solvent-evaporation technique, as described previously (Wafa et al., 2017). In brief, 75 μl of 1% w/v poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) (Mowiol 8-88; MilliporeSigma, Allentown, PA) containing 3 mg of chicken egg-white OVA (MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, MO) was sonicated for 30 seconds into 1.5 ml of dichloromethane (MilliporeSigma) containing 200 mg of 20:80 CPTEG:CPH copolymer. The primary emulsion obtained was immediately emulsified into 8 ml of 1% w/v PVA solution (under the same previous conditions). The resulting emulsion was instantly added to 22 ml of 1% w/v PVA solution and stirred in a fume hood for 2 hours to allow evaporation of dichloromethane. After 2 hours, particles were collected at 2880g, for 5 minutes. The particles obtained were washed twice with sterile nanopure water. The particle suspension was frozen at −80°C for 1 hour and subsequently lyophilized for 24 hours Finally, particles were collected in a sealed container and stored at −20°C until used. Empty (i.e., no protein) polyanhydride particles, for assessing the stimulatory effect of polyanhydride particles on DCs, were also prepared using the same method, except that the internal aqueous phase (i.e., 1% w/v PVA) had no OVA. To evaluate the uptake efficiency by DCs, a hydrophobic model drug coumarin-6 (C6) (MW: 350.43 g/mol) (MilliporeSigma) was loaded into the particles using the same technique as described above with only one exception: 200 μg of C6 was added to the oil phase (i.e., dichloromethane) into which the polymer was already dissolved. C6 is a photoluminescent compound, and it has been widely used to perform cell uptake studies (Behroozi et al., 2018; Dilnawaz and Sahoo, 2018; Tian et al., 2018).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of 20:80 CPTEG:CPH polyanhydride copolymer.

Particle Characterization.

Polyanhydride particles were characterized in terms of size, shape, and surface charge. Suspensions of particles in nanopure water were used to measure particle properties. Size distribution and surface charge were measured using a Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument (Malvern, Southborough, MA), as described previously (Wafa et al., 2017). The size was measured using dynamic light scattering at a back-scattering angle of 173° and the net charge on particle surfaces was measured using laser Doppler electrophoresis at a forward-scattering beam angle of 13°. Particles were also examined for their shape and surface morphology using a Hitachi S-4800 scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Hitachi High-Technologies, Ontario, Canada), as described previously (Wafa et al., 2017). Silicon wafer chips (Ted Pella Inc., Redding, CA) doped with polyanhydride particles and mounted on a flat SEM pin stub were coated with gold-palladium using an argon beam K550 sputter coater (Emitech Ltd., Kent, UK) for 3 minutes. Subsequently, SEM photomicrographs were captured at 2 kV accelerating voltage, and images were processed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

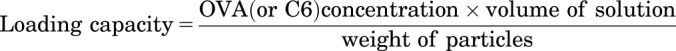

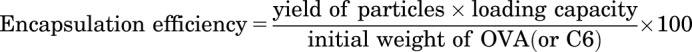

Quantification of OVA-Loaded and C6-Loaded Polyanhydride Particles

OVA content in polyanhydride particles was measured using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay, as described previously (Wafa et al., 2017). In brief, OVA-loaded particles were treated with 1 ml of 0.2 N NaOH and incubated overnight in an orbital incubator shaker (New Brunswick Scientific Co. Inc., Edison, NJ) set at 37°C and 300 rpm. A Micro BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) was used to determine the protein concentration in the samples after being neutralized by 0.3 N HCl. Subsequently, samples were stepwise diluted using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (MilliporeSigma) in 96-well plates (Celltreat, Pepperell, MA) and incubated with Micro BCA reagents for 2 hours at 37°C. After incubation, the absorbance of the solutions at 562 nm was measured using a SpectraMax Plus 384 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Bovine serum albumin standard solution was used to generate the standard curve under the same conditions and three replicates of all samples were assayed. The results were expressed as micrograms of OVA per milligram of particles, as described in eq. 1. The percent encapsulation efficiency was expressed as the percentage of the total OVA entrapped to the amount of OVA used to prepare the formulation, as described in eq. 2. Additionally, the amount of C6 entrapped in polyanhydride particles was quantified by measuring the fluorescence intensity. Briefly, C6-loaded polyanhydride particles were dissolved in chloroform (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) and the fluorescence intensity of C6 was measured at excitation/emission wavelengths of 405/495 nm, using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices). A standard curve of C6 in chloroform was also generated. All samples were run in triplicate, and the means with S.D. were reported. Likewise, the loading capacity and encapsulation efficiency were calculated as described in eqs. 1 and 2.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

In Vitro Release of OVA

Samples of 20:80 CPTEG:CPH polyanhydride particles encapsulating OVA (∼30 mg) were dispersed into 5 ml of PBS and incubated in the orbital incubator shaker set at 37°C and 300 rpm for 1 month. The amount of OVA released from particles into the medium was measured at predetermined time intervals (1, 12 hours, 1, 2, 4, 7, 10, 14, 20, and 30 days), aliquots (0.5 ml) of the release medium were withdrawn, and the total volume was replenished by fresh PBS at each time interval. Supernatants were stored at −20°C until OVA content was measured by the BCA protein assay (as described above). The experiment was performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as the mean of cumulative OVA-release into PBS determined as a function of time ± S.D.

In Vitro Experiments with DCs

Quantitative and qualitative cellular uptake and subsequent stimulatory effects of polyanhydride particles on DCs were studied. DCs were derived from the bone marrow of C57BL/6J mice as previously described (Liu et al., 2018). Briefly, bone marrow cells were extracted from the femur and tibia, and were grown on bacteriological Petri dishes in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI 1640) supplemented with: 10 mM HEPES buffer, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM minimal essential medium nonessential amino acids MEM-NEAA, 2 mM GlutaMAX (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (MilliporeSigma), 50 ng/ml gentamicin sulfate (IBI Scientific, Peosta, IA), 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA), and 20 ng/ml of murine granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), in a humidified incubator at 37°C containing 5% CO2. Bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) were harvested at day 10 of culture, seeded in 12-well Cellstar plates (Greiner Bio-One, Germany) at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well, and incubated for 6 hours prior to treatment. This was followed by addition of polyanhydride particles (delivering a total dose of 0.02 μg C6-loaded or empty particles at equivalent amount) and incubation for either 1–4 hours for uptake studies or 24 hours to assess BMDC activation and maturation. After incubation with designated treatments, cells were collected (without using trypsin; instead vigorous flushing was implemented) and centrifuged (230g) for 5 minutes at 4°C. In the DC-stimulation experiment, cell culture supernatants were harvested and assayed for IL-10 and IL-12p70 levels using a cytokine-specific mouse enzyme-linked immune-sorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Diego, CA), per manufacturer’s instructions. Cells treated with empty particles were stained with anti-CD11c-FITC and either anti-CD80-PE or anti-CD86-PE (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) using a standard direct immunofluorescence method. Controls involved staining DCs with FITC- or phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated isotype-matched negative control antibodies. All cell samples (including quantitative uptake study) were run through a BD FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) in triplicate and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Additionally, the uptake of C6-loaded polyanhydride particles was examined qualitatively using Leica TCS SP8 STED confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL). Briefly, BMDCs were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well (in supplemented medium) in a four-well Nunc Laboratory-Tek Chamber glass slide system (Nunc, Rochester, NY) coated with poly-l-lysine hydrobromide (MW: 30,000–70,000) (MilliporeSigma) to promote DC attachment and incubated overnight in a well-controlled environment at 37°C with 5% CO2. This was followed by addition of polyanhydride particles (delivering a total dose of 0.02 μg C6), with untreated cells left as a control, and incubation for 4 hours. After incubation, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed with prewarmed (to 37°C) 1× Hank’s balanced salt solution (Life Technologies/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Eugene, OR). Subsequently, specimens were stained with CellMask Orange plasma membrane stain, Texas Red-X phalloidin, and ProLong Gold antifade reagent DAPI (Life Technologies), respectively, per the manufacturer’s instructions. The specimens were visualized using the confocal laser scanning microscope, and the images were processed with ImageJ-based Fiji software.

Animal Studies

Mouse Strains.

A murine tumor model was used for the evaluation of prophylactic cancer vaccine formulations. Wild-type female C57BL/6J mice (8–10 weeks of age) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were housed at the Medical Laboratories at the University of Iowa and kept on a daily 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the University of Iowa guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Vaccination.

To assess the polyanhydride vaccine in vivo, 40 mice were randomly divided into four groups (n = 10 mice per group) and treated with subcutaneous (rear dorsal flank) injections: (I) naïve (i.e., unvaccinated), (II) single dose (primed on day 0 only), (III) prime-boost (days 0/7), and (IV) prime-boost (days 0/21). Prepared polyanhydride particles were dispersed in 1× Dulbecco’s PBS (pH 7.4) solution (Life Technologies/Thermo Fisher Scientific) immediately prior to vaccination. Mice in group II received a single dose of 50 μg of OVA, and mice in groups III and IV received two doses of 50 μg of OVA (i.e., prime-boost). On days 14 and 28 post–prime vaccination, tumor-specific CD8+ T cells were measured in the peripheral blood harvested through submandibular bleeds. On day 28 post–prime vaccination, tumor-specific IgG1 and IgG2C antibody titers were measured in the serum harvested through submandibular bleeds. A week later, mice were challenged with tumor cells.

Assessment of Vaccine-Induced Antitumor Immune Responses.

Cell-Mediated Immunity.

Using a submandibular bleeding technique, approximately 180 μl of mouse peripheral blood was collected into tubes containing 3 ml of ACK (ammonium-chloride-potassium) red blood cell lysing buffer, and the samples were incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes. After incubation, peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) were washed twice with complete medium using Eppendorf Centrifuge 5804-R set at 230g, 4°C, for 5 minutes. Then, PBLs were resuspended in 150 μl of ice-cold PBS [containing 5% fetal bovine serum and 0.1% sodium azide (FACS buffer)] and transferred to V-bottomed 96-well plates (Corning, Kennebunk, ME) on a bed of ice (as with all subsequent incubations). This was followed by centrifugation (per the conditions described above), discard of supernatants, resuspension of PBLs in 50 μl of anti-mouse CD16/CD32 Fc receptor block (clone 93) (eBioscience) in FACS buffer, and incubation for 15 minutes. Subsequently, 50 μl of H-2Kb SIINFEKL class I iTAg MHC tetramer (Kb-OVA257) labeled with PE (MBLI, Woburn, MA), diluted 1/100 in FACS buffer, was added in darkness and samples were incubated for 30 minutes. After incubation, 100 μl of a mixture of FITC-labeled rat anti-mouse CD8 (1 μg/ml) and PE-Cy5-labeled hamster anti-mouse CD3 (eBioscience) (1 μg/ml) antibodies in FACS buffer was added in darkness and incubated for 20 minutes. After incubation, PBLs were washed twice with FACS buffer to remove the unbound antibodies. Subsequently, 100 μl of 1× BD Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was added and incubated for 10 minutes in the dark, then 100 μl of perm/wash buffer (BD Biosciences) was added, followed by centrifugation for 15 minutes at 660g and 4°C. Finally, PBLs were resuspended in FACS buffer, and samples were acquired using a BD FACScan flow cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo software. Results were expressed as percentage of total CD3+ CD8+ T lymphocytes in peripheral blood that were positive for tetramer staining.

Levels of OVA-Specific Antibody.

The titers of tumor-specific IgG antibodies, IgG1 and IgG2C, were measured using ELISA as described previously (Wafa et al., 2017). In brief, mice were bled from the submandibular area, and to harvest sera, blood samples were incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. After incubation, blood clots were removed using clean tweezers and the samples were centrifuged for 10 minutes using an Eppendorf Centrifuge 5804-R set at 3000g and 4°C. Supernatants (sera) were collected and stored at −80°C until use. Meanwhile, Immulon 2HB flat-bottom microtiter 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated with 100 μl of PBS containing 0.5 μg of OVA. Using OVA-coated plates and PBS containing 0.05% v/v Tween-20 (MilliporeSigma), sera samples were serially diluted and incubated overnight at room temperature. This was followed by incubation for 3 hours at room temperature with either goat anti-mouse IgG1 (or goat anti-mouse IgG2C) antibody conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). Subsequently, 100 μl of p-nitrophenylphosphate in Tris buffer (MilliporeSigma) was added in the dark. After 30 minutes, the absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a SpectraMax Plus 384 microplate reader. To remove any proteins or antibodies that were not specifically bound, plates were washed three times with 150 μl of PBS/Tween-20 solution between all reagent addition steps. The reciprocal of mouse sera dilution (highest dilution at which the absorbance was three-times greater than those of negative control) was reported as serum antibody titer.

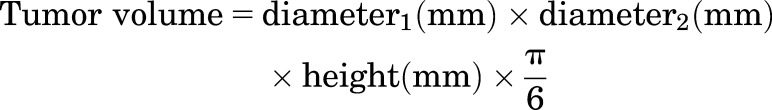

Tumor Challenge.

Five weeks post–prime vaccination, all mice were subcutaneously challenged with 2 × 106 E.G7-OVA cells, purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA), suspended in 100 μl of sterile 1× Dulbecco’s PBS. Cells were injected contralaterally to the vaccination site. Tumor progression was monitored regularly over time for the subsequent 2 months (using a digital caliper) and tumor volumes were calculated as described in eq. 3. To minimize pain and discomfort, mice were euthanized when the tumor size exceeded 20 mm at the largest diameter or 10 mm in height.

|

(3) |

Statistical Analysis.

Data were initially analyzed by one-way analysis of variance using F-test, which was followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparison test to compare all pairs of treatments. Initial analysis of survival data was performed by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test using GraphPad-Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), further statistical analysis was made by pairwise comparisons, and data were analyzed using log-rank test (Tukey-Kramer adjusted). In all tests, differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Properties of Polyanhydride Particles.

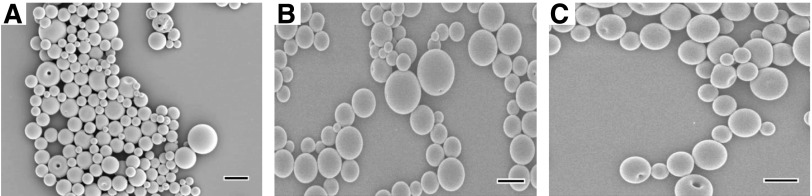

All 20:80 CPTEG:CPH particle formulations were prepared by a double-emulsion method and had an average diameter of less than 1 μm (Table 1). In addition, particles exhibited a narrow size distribution with an average polydispersity index value of <0.2. Also, particles possessed a negative surface charge regardless of payload as indicated by the average zeta potential measurements. The loading capacity of OVA was low, and the encapsulation efficiency of OVA was only 28%, whereas the encapsulation efficiency of C6 was relatively high (>70%). The low encapsulation efficiency of water-soluble OVA was expected since 20:80 CPTEG:CPH is a hydrophobic copolymer as indicated by its chemistry and as demonstrated by the high contact angle (Ө) between water droplets and polymer, as previously reported (Ө > 90°) (Wafa et al., 2017). The analysis of SEM photomicrographs revealed that particles were spherical in shape and possessed smooth surfaces (Fig. 2.1). In vitro release kinetics of OVA from polyanhydride particles showed a rapid burst release phase followed by a slower sustained release phase (Fig. 2.2A). By day 30, the cumulative release of OVA from 20:80 CPTEG:CPH particles had reached 50%. Subsequent to the burst release phase, the release of OVA approximated to zero-order kinetics (Fig. 2.2B).

Table 1.

Properties of polyanhydride particles

Data are presented as mean ± S.D.

| OVA-Loaded Particles | C6-Loaded Particles | Empty Particles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle size (d.nm) | 959 ± 20 | 913 ± 22 | 926 ± 17 |

| Polydispersity index | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| Zeta potential (mV) | −31.3 ± 2.8 | −26.5 ± 0.2 | −26.1 ± 0.2 |

| Loading capacity (μg/mg of particles) | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 0.74 ± 0.02 | — |

| Encapsulation efficiency (%) | 28.0 ± 0.9 | 73.9 ± 1.6 | — |

d.nm, diameter in nanometers; —, not done.

Fig. 2.1.

SEM images of 20:80 CPTEG:CPH polyanhydride particles. (A) OVA-loaded particles; (B) C6-loaded particles; (C) empty particles. Scale bar, 1 μm.

In Vitro Experiments with BMDCs.

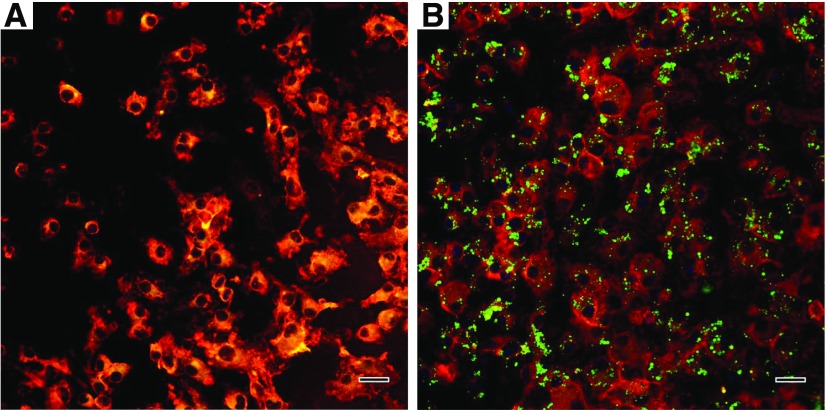

BMDCs were harvested at day 10 of culture, at which point nearly 90% of the cells were CD11c-positive as analyzed by the BD FACScan flow cytometer (data not shown). Results of surface staining of BMDCs revealed that polyanhydride particles promoted the upregulation of both CD80 and CD86 to levels significantly greater than untreated BMDCs (t test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3.1A). This further demonstrates that polyanhydrides possess properties of a self-adjuvant. In addition, it was observed that polyanhydride particles could induce IL-12p70 secretion to a greater extent than IL-10 secretion (t test, P < 0.001), and it was found that BMDCs exposed to polyanhydride particles produced significantly high concentrations of IL-10 and IL-12p70 compared with untreated BMDCs (t test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3.1B). Cellular uptake studies indicated that polyanhydride particles were readily and efficiently internalized by DCs as demonstrated by the significant shift in the median fluorescence intensity (Fig. 3.1C), and the uptake efficiency at 4 hours was significantly greater than at 1 hour (t test, P < 0.001). The quantitative uptake results were supported by the confocal microscopy images, where it was evident that each DC was able to internalize several particles (Fig. 3.2).

Fig. 3.1.

In vitro BMDC stimulation with, and uptake of, polyanhydride particles. (A) CD80/CD86 expression on the cell surface (flow cytometry) of BMDCs and (B) IL-10 and IL-12p70 concentrations in the cell-culture supernatants (ELISA) after a 24-hour incubation with empty polyanhydride particles. (C) uptake study by BMDCs of C6-loaded polyanhydride particles at two time points: 1 and 4 hours.

Assessment of Immunogenicity of OVA-Loaded 20:80 CPTEG:CPH Polyanhydride Particles.

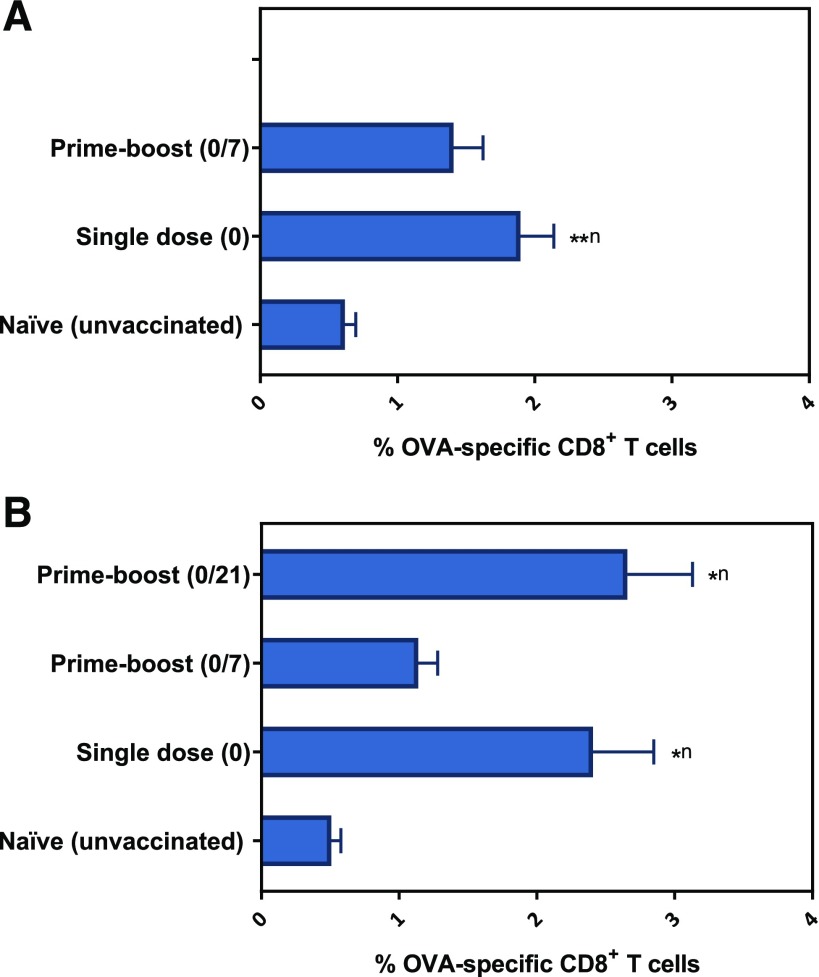

Immunocompetent mice were vaccinated with a single dose, a prime-boost (with a 7-day interval), or a prime-boost (with a 21-day interval) of OVA-loaded 20:80 CPTEG:CPH polyanhydride particles. The percentage of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood measured 2 weeks post–prime immunization was found to be increased in mice administered a single-dose vaccine compared with naïve mice, whereas mice receiving the prime-boost (days 0/7) regimen demonstrated increased, but not significant, percentages of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood compared with naïve mice (Fig. 4.1A). On day 28 post–prime immunization, it was found that the percentage of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells in mice receiving the single-dose and prime-boost (day 0/7) regimens were similar to those obtained on day 14. In addition, administering a booster immunization on day 21 did not have a significant impact on OVA-specific CD8+ T-cell levels compared with that induced by the single-dose formulation (Fig. 4.1B). In contrast, humoral OVA-specific immune responses, particularly IgG1 titers, were observed to significantly improve upon administration of a booster dose either 7 or 21 days post-prime as evidenced by serum titers two orders of magnitude higher than that obtained in sera of mice receiving a single dose (Fig. 4.2).

Fig. 4.1.

Percentage of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood of mice vaccinated with different polyanhydride-based vaccine regimens. The percentage of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells was measured at two-time points: (A) Two weeks (data from single-dose and prime-boost 0/21 groups were combined since mice in both groups received only one dose) and (B) 4 weeks post–prime vaccination. Data are plotted as mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Superscript n = compared with naïve group.

Evaluation of Tumor Progression and Survival.

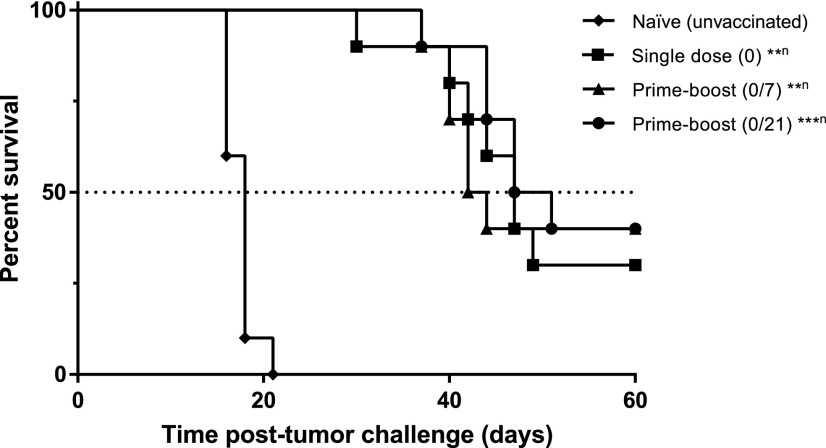

Five weeks (day 35) post–prime vaccination, mice were challenged with a lethal dose of OVA-expressing E.G7 cells, and tumor growth and survival were subsequently recorded. As expected, naïve mice had tumors that grew rapidly compared with vaccinated mice (Fig. 5.1, A–D). The vaccine regimen study with 20:80 CPTEG:CPH particles encapsulating OVA showed that all vaccinated mice had slow to no tumor growth in comparison with unvaccinated mice during the first 18 days post–tumor challenge. The average tumor volume, as illustrated in Fig. 5.1E, supports this observation: The average tumor volume curves of vaccinated mice were significantly below than that of naïve mice, as demonstrated by the one-way analysis of variance performed on day 16 data (P < 0.05). Furthermore, all vaccine regimens led to 30%–40% of mice being tumor-free at the end of the study (i.e., day 60 post–tumor challenge) (Fig. 5.1F). These mice were monitored for another 40 days (i.e., up to day 100) and were not found to have developed any recurrent tumors. Survival analysis revealed that all vaccine regimens resulted in a statistically significant extended survival compared with naïve control, but no significant statistical differences were observed among vaccine regimens (Fig. 5.2). The median survival times of unvaccinated (naïve) mice and mice vaccinated with a single dose, a prime-boost (on days 0 and 7), or a prime-boost (on days 0 and 21) were 18, 47, 43, and 49 days, respectively.

Fig. 5.1.

Prophylactic antitumor effect of vaccinating mice with different polyanhydride-based vaccine regimens. Mice were vaccinated as indicated and subsequently challenged with E.G7-OVA cells 35 days post prime. (A–D) Each curve represents the tumor growth for each individual mouse. (E) Average tumor volume (data are plotted as mean + S.E.M.): naïve (♦); single-dose regimen (▪); prime-boost (0/7) regimen (6); prime-boost (0/21) regimen (•). (F) Percent tumor-free mice on days 16 (last day that all naïve mice were alive) and 60 (end of study) post–tumor challenge.

Discussion

Herein, we have compared three distinct polyanhydride-based vaccine regimens in terms of: 1) inducing antigen-specific humoral and cellular immune responses; and 2) subsequently protecting against tumor challenge. Side-by-side comparisons of a single-dose versus two temporally distinct prime-boost regimens involving OVA-loaded 20:80 CPTEG:CPH particles were carried out. We have previously shown that polyanhydride-based particles were capable of stimulating significant OVA-specific cellular immune responses (Wafa et al., 2017) and that, unlike other previously tested polymers that require the presence of a TLR agonist to promote significant cellular immune responses, polyanhydride-based particles have inherent capacity to stimulate TLRs (TLR-2, -4, and -5) (Tamayo et al., 2010). Previously, we have only studied these promising polymers for cancer vaccines in the context of a specific prime-boost regimen (Joshi et al., 2013; Wafa et al., 2017). In this work, we examined the effects of the number, as well as timing, of polyanhydride particle immunizations on antitumor humoral and cellular immune responses.

Analysis of the OVA-release kinetics from the polyanhydride-based particles in vitro revealed a burst release (approximately 28% of encapsulated OVA) that probably corresponded to OVA loaded at, or near, the surface of particles. Possible explanations for this observation include: 1) a propensity of the payload to diffuse to the surface, forming a concentration gradient during the fabrication process (during the solvent evaporation step) (Haughney et al., 2013), and/or 2) water molecules eliminated during the freeze-drying process carrying some of the payload to the surface (Kamaly et al., 2016). The burst release was followed by slow and sustained release of OVA over time, owing to the fact that polyanhydride particles predominately degrade through surface erosion (i.e., degradation is limited to the surface) (Katti et al., 2002; Shen et al., 2002; Torres et al., 2006). Assuming that a similar release profile occurs in vivo, it is therefore probable that a substantial number of OVA (50%–60%) remained in association with the particles for at least 2 weeks post-prime and was therefore available for uptake by DCs. This is important since it is widely recognized that delivery of antigen in particulate form (e.g., conjugated to, or encapsulated by, microparticles or nanoparticles) has a greater tendency to stimulate a cellular immune response than antigen in soluble form (Storni et al., 2005; Nembrini et al., 2011). Uptake studies showed that polyanhydride particles were efficiently taken up by BMDCs. DCs exposed to polyanhydride particles demonstrated significant increases in cytokine secretion and CD80/CD86 expression. The expression of these maturation markers contributes to their potency in subsequently activating CD8+ T cells (Acuto and Michel, 2003; Liu et al., 2018). These observations have important implications for developing antitumor responses in hosts with cancer cells.

The efficacy of each vaccine regimen was assessed in terms of cellular and humoral OVA-specific immune responses as well as antitumor activity in vivo. Although vaccines for cancer treatment have drawn considerable attention in the past few years (Acres et al., 2004; Guo et al., 2013; Finn, 2014), there is a dearth of data adequately documenting the association between the particle-based cancer vaccine administration strategy and the potency of the subsequent antitumor immune responses. One of the potentially promising outcomes of polymer particle-based vaccines is that they may provide an opportunity for convenient single-dose vaccinations, primarily because of their release kinetics. However, most researchers have approached preclinical studies with particle-based vaccines using more conventional prime-boost approaches or without directly comparing temporally distinct prime-boost regimens. Given the vast array of vaccine formulations being generated, it would be of great benefit to understand the ramifications of using different vaccination strategies with different formulations not only in the context of cancer treatment but also in the context of other diseases. In this study, a single-dose regimen and two dual-dose (prime-boost) vaccine regimens were compared. Administering the booster vaccine dose (irrespective of the time interval) supported the induction of relatively strong OVA-specific antibody (IgG1-dominated) immune responses in comparison with single-dose vaccination, which was two orders of magnitude weaker (Fig. 4.2). Interestingly, prime-boosts were not necessary for generation of significant increases in the levels of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4.1). Thus, in terms of generating substantive humoral responses using antigen-loaded polyanhydride particles, a prime-boost regimen was required. However, a prime-boost appears to be unnecessary for the enhanced induction of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. An explanation, albeit speculative for the findings with respect to humoral responses is that there was insufficient activation of T-dependent antibody responses when the single-dose vaccine was applied, possibly owing to limited helper T cell-mediated activation. This may have been the result of either insufficient presentation of antigen in the context of MHC class II and/or insufficient TLR stimulation. In other words, the supply of antigen and/or adjuvant (in this case the polymer) may have been limiting in terms of dose and/or duration. Further experiments such as doubling the dosage amount of the single-dose vaccine may help determining if such a situation is probable.

The prophylactic protection against tumor challenge and overall survival provided by a single-dose polyanhydride-based vaccine was comparable to that provided by prime-boost vaccine regimens. These results emphasize the effectiveness of a single dose of the polyanhydride particle-based vaccine in generating significant and enduring cell-mediated immunity as well as protecting against tumor progression. The fact that a single-dose vaccination was able to generate an anti-OVA CD8+ T-cell response that was sustained until at least day 28 is highly promising. It would be of great value if future experiments investigated the qualitative nature of the cellular immune responses generated by these particle-based formulations in terms of the generation of central and effector memory T cells. In addition, it would be of interest to observe what effect using these polyanhydride-based vaccines would have in a heterologous vaccination setting. Based on the findings here and combined with the previously reported pathogen-mimicking properties of polyanhydride particles, it appears that these protein-loaded particles have beneficial effects on both B-cell and T-cell immunity like attenuated adenoviruses. If so, these particle-based cancer vaccines may have advantages in terms of clinical applications since issues of safety and neutralizing antibodies would be avoided. Further investigations into heterologous vaccination regimens and qualitative memory T-cell responses are future goals. Mechanistically, it is probable that the antitumor effect of the vaccines used here was attributable, at least in part, to the generation of OVA-specific T cells; however, depletion of various lymphocyte subsets would be required in the future to confirm this. Finally, it would also be of interest to investigate the effectiveness of polyanhydride particle-based vaccines and vaccination schedules in the context of a therapeutic model in the presence of immune checkpoint-specific antibodies.

In summary, this study demonstrated that a single vaccination dose of 20:80 CPTEG:CPH polyanhydride particles provided OVA-specific CD8+ T-cell responses and antitumor activities quantitatively similar to those generated by prime-boost vaccination regimens. This can potentially obviate the need for a multiple-dose vaccine course of cancer treatment, or at least reduce the number of vaccinations required to achieve effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the Iowa State University Nanovaccine Institute, the Vlasta Klima Balloun Faculty Chair, the National Institutes of Health (1U01CA213862-01A1 and P30 CA086862), and the Lyle and Sharon Bighley Chair of Pharmaceutical Sciences. Authors declare that there is no conflict of interests to disclose.

Abbreviations

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

- BMDCs

bone marrow-derived DCs

- C6

coumarin-6

- CPH

1,6-bis(p-carboxyphenoxy) hexane

- CPTEG

1,8-bis(p-carboxyphenoxy)-3,6-dioxaoctane

- DCs

dendritic cells

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immune-sorbent assay

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- OVA

ovalbumin

- PBLs

peripheral blood lymphocytes

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PE

phycoerythrin

- PVA

poly(vinyl alcohol)

- SEM

scanning electron microscope

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Wafa, Geary, Salem.

Conducted experiments: Wafa, Geary, Ross, Goodman.

Performed data analysis: Wafa.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Wafa, Geary, Ross, Narasimhan, Salem.

Footnotes

References

- Acres B, Paul S, Haegel-Kronenberger H, Calmels B, Squiban P. (2004) Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Curr Opin Mol Ther 6:40–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuto O, Michel F. (2003) CD28-mediated co-stimulation: a quantitative support for TCR signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 3:939–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed KK, Geary SM, Salem AK. (2014) Applying biodegradable particles to enhance cancer vaccine efficacy. Immunol Res 59:220–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfarouk KO, Stock CM, Taylor S, Walsh M, Muddathir AK, Verduzco D, Bashir AH, Mohammed OY, Elhassan GO, Harguindey S, et al. (2015) Resistance to cancer chemotherapy: failure in drug response from ADME to P-gp. Cancer Cell Int 15:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen MH, Schrama D, Thor Straten P, Becker JC. (2006) Cytotoxic T cells. J Invest Dermatol 126:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behroozi F, Abdkhodaie MJ, Abandansari HS, Satarian L, Molazem M, Al-Jamal KT, Baharvand H. (2018) Engineering folate-targeting diselenide-containing triblock copolymer as a redox-responsive shell-sheddable micelle for antitumor therapy in vivo. Acta Biomater 76:239–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum JS, Wearsch PA, Cresswell P. (2013) Pathways of antigen processing. Annu Rev Immunol 31:443–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo BM, Lacave R, Pioche-Durieu C, Masurier C, Lemoine FM, Guigon M, Klatzmann D. (2000) Cellular but not humoral immune responses generated by vaccination with dendritic cells protect mice against leukaemia. Immunology 99:8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Barros CM, Wafa EI, Chitphet K, Ahmed K, Geary SM, Salem AK. (2017) Production of adjuvant-loaded biodegradable particles for use in cancer vaccines. Methods Mol Biol 1494:201–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilnawaz F, Sahoo SK. (2018) Augmented anticancer efficacy by si-RNA complexed drug-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles in lung cancer therapy. ACS Appl Nano Mater 1:730–740. [Google Scholar]

- Finn OJ. (2014) Vaccines for cancer prevention: a practical and feasible approach to the cancer epidemic. Cancer Immunol Res 2:708–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana F, Liu D, Hirvonen J, Santos HA. (2017) Delivery of therapeutics with nanoparticles: what’s new in cancer immunotherapy? Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 9, DOI: 10.1002/wnan.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Cremades M, Pitou C, Iversen PW, Troconiz IF. (2017) Characterizing gemcitabine effects administered as single agent or combined with carboplatin in mice pancreatic and ovarian cancer xenografts: a semimechanistic pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics tumor growth-response model. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 360:445–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary SM, Hu Q, Joshi VB, Bowden NB, Salem AK. (2015) Diaminosulfide based polymer microparticles as cancer vaccine delivery systems. J Control Release 220 (Pt B):682–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez de Cedrón M, Vargas T, Madrona A, Jiménez A, Pérez-Pérez MJ, Quintela JC, Reglero G, San-Félix A, Ramírez de Molina A. (2018) Novel polyphenols that inhibit colon cancer cell growth affecting cancer cell metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 366:377–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, Manjili MH, Subjeck JR, Sarkar D, Fisher PB, Wang XY. (2013) Therapeutic cancer vaccines: past, present, and future. Adv Cancer Res 119:421–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughney SL, Petersen LK, Schoofs AD, Ramer-Tait AE, King JD, Briles DE, Wannemuehler MJ, Narasimhan B. (2013) Retention of structure, antigenicity, and biological function of pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) released from polyanhydride nanoparticles. Acta Biomater 9:8262–8271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine DJ, Swartz MA, Szeto GL. (2013) Engineering synthetic vaccines using cues from natural immunity. Nat Mater 12:978–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain JP, Modi S, Domb AJ, Kumar N. (2005) Role of polyanhydrides as localized drug carriers. J Control Release 103:541–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi VB, Geary SM, Carrillo-Conde BR, Narasimhan B, Salem AK. (2013) Characterizing the antitumor response in mice treated with antigen-loaded polyanhydride microparticles. Acta Biomater 9:5583–5589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamaly N, Yameen B, Wu J, Farokhzad OC. (2016) Degradable controlled-release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: mechanisms of controlling drug release. Chem Rev 116:2602–2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katti DS, Lakshmi S, Langer R, Laurencin CT. (2002) Toxicity, biodegradation and elimination of polyanhydrides. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 54:933–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahariya C. (2016) Vaccine epidemiology: a review. J Family Med Prim Care 5:7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LC, Deng J, Stephens D. (2002) Polyanhydride implant for antibiotic delivery--from the bench to the clinic. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 54:963–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wang K-H, Chen H-Y, Li J-R, Laurence TA, Ly S, Liu F-T, Liu G-Y. (2018) Periodic arrangement of lipopolysaccharides nanostructures accelerates and enhances the maturation processes of dendritic cells. ACS Appl Nano Mater 1:839–850. [Google Scholar]

- Maher J, Davies ET. (2004) Targeting cytotoxic T lymphocytes for cancer immunotherapy. Br J Cancer 91:817–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Lostao L, Anel A, Pardo J. (2015) How do cytotoxic lymphocytes kill cancer cells? Clin Cancer Res 21:5047–5056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nembrini C, Stano A, Dane KY, Ballester M, van der Vlies AJ, Marsland BJ, Swartz MA, Hubbell JA. (2011) Nanoparticle conjugation of antigen enhances cytotoxic T-cell responses in pulmonary vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:E989–E997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paci A, Veal G, Bardin C, Levêque D, Widmer N, Beijnen J, Astier A, Chatelut E. (2014) Review of therapeutic drug monitoring of anticancer drugs part 1--cytotoxics. Eur J Cancer 50:2010–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J, Chambers A, Spithoff K, Laperriere N. (2007) Gliadel wafers in the treatment of malignant glioma: a systematic review. Curr Oncol 14:189–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuschenbach M, von Knebel Doeberitz M, Wentzensen N. (2009) A systematic review of humoral immune responses against tumor antigens. Cancer Immunol Immunother 58:1535–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy J, Adili R, Kulmacz R, Holinstat M, Das A. (2016) Development of poly unsaturated fatty acid derivatives of aspirin for inhibition of platelet function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 359:134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen E, Kipper MJ, Dziadul B, Lim MK, Narasimhan B. (2002) Mechanistic relationships between polymer microstructure and drug release kinetics in bioerodible polyanhydrides. J Control Release 82:115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. (2017) Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 67:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist C-A. (2013) 2 - Vaccine immunology A2 - Plotkin, Stanley A, in Vaccines, 6th ed, (Orenstein WA, Offit PA. eds) pp 14–32, W.B. Saunders, London. [Google Scholar]

- Storni T, Kündig TM, Senti G, Johansen P. (2005) Immunity in response to particulate antigen-delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 57:333–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo I, Irache JM, Mansilla C, Ochoa-Repáraz J, Lasarte JJ, Gamazo C. (2010) Poly(anhydride) nanoparticles act as active Th1 adjuvants through Toll-like receptor exploitation. Clin Vaccine Immunol 17:1356–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian F, Dahmani FZ, Qiao J, Ni J, Xiong H, Liu T, Zhou J, Yao J. (2018) A targeted nanoplatform co-delivering chemotherapeutic and antiangiogenic drugs as a tool to reverse multidrug resistance in breast cancer. Acta Biomater 75:398–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres MP, Determan AS, Anderson GL, Mallapragada SK, Narasimhan B. (2007) Amphiphilic polyanhydrides for protein stabilization and release. Biomaterials 28:108–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres MP, Vogel BM, Narasimhan B, Mallapragada SK. (2006) Synthesis and characterization of novel polyanhydrides with tailored erosion mechanisms. J Biomed Mater Res A 76:102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wafa EI, Geary SM, Goodman JT, Narasimhan B, Salem AK. (2017) The effect of polyanhydride chemistry in particle-based cancer vaccines on the magnitude of the anti-tumor immune response. Acta Biomater 50:417–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Qiao S-L, Wang H. (2018) Facile synthesis of peptide cross-linked nanogels for tumor metastasis inhibition. ACS Appl Nano Mater 1:785–792. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Wang W, Wang S. (2015) Effect of vaccine administration modality on immunogenicity and efficacy. Expert Rev Vaccines 14:1509–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, You W, Sun G, Li Y, Chen B, Ai J, Jiang H. (2016) The marine-derived oligosaccharide sulfate MS80, a novel transforming growth factor β1 inhibitor, reverses epithelial mesenchymal transition induced by transforming growth Factor-β1 and suppresses tumor metastasis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 359:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]