Abstract

Background

This study was aimed to investigate whether measurement of free testosterone and cortisol in saliva is a reliable alternative to their assessment in serum for monitoring physical fitness in professional athletes.

Methods

We studied 25 members of the soccer team Parma F.C., playing in Italian major football league. Blood and saliva samples were collected at fasting, before a regular training session. Cortisol, total and free testosterone, as well as the ratio between free testosterone and cortisol, were assessed in paired serum and saliva samples, and their results were compared.

Results

An excellent correlation was found between serum and saliva cortisol (r = 0.751; P < 0.001). A significant correlation was also observed between free testosterone in serum and saliva (r = 0.590; P = 0.002), whereas no significant correlation was found between total testosterone in serum and saliva (r = 0.181; P = 0.387). A significant correlation was found for the free testosterone to cortisol ratio in serum and saliva (r = 0.43; P = 0.031). All athletes (25/25; 100%) declared that they would feel more comfortable to have saliva rather than blood serially collected.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that measurement of free testosterone and cortisol in saliva may be seen as a reliable alternative to their assessment in serum.

Keywords: cortisol, free testosterone, saliva, sports, testosterone

INTRODUCTION

Competitive soccer, such as playing in a major national football league, produces a considerable stress, which especially involves the musculoskeletal, endocrine, nervous, and immune systems 1, and may ultimately impact on athletic performance 2. In particular, when the balance between training stress and recovery is impaired, medium‐ and long‐term decay of performance occurs, leading to overreaching and possibly overtraining 3. Functional overreaching is conventionally defined a physiological reduction of performance which usually lasts for less than 2 weeks, and is then accompanied by complete recovery and a supercompensatory effect 3. Overtraining is instead defined as a dramatic decay of performance due to excessive training volume or intensity, which typically requires weeks or months for recovery 3.

The measurement of hormones, especially cortisol, testosterone, and their ratios, is one of the mostly used means for distinguishing overreaching from over‐training in various sports disciplines, including soccer 1, 4. In particular, the free testosterone to cortisol ratio is now widely used for early detection of an imbalance between anabolic and catabolic metabolism, thus providing valuable information for predicting progression from overreaching to overtraining 5, 6. Importantly, these hormones are conventionally measured in serum or plasma. Due to considerable progresses in analytical techniques occurred in recent years, a large number of endogenous and exogenous compounds can now be measured in a vast array of biological fluids, including blood, serum, plasma, urine, sweat, and even saliva 7. Among these, the use of saliva is regarded as a valuable perspective from both an analytical and practical perspective. The fluctuation of several hormones in blood in response to exercise is in fact closely mirrored by a change in their saliva concentration 8, but saliva can also be collected easily, rapidly, frequently, and without the stress caused by a venipuncture 9. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate whether the measurement of free testosterone and cortisol in saliva may be considered a reliable alternative to their measurement in serum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study population consisted of 25 members of the soccer team Parma F.C., playing in the Italian major football league (i.e., “Serie A”). Venous blood samples were collected in the morning, at fasting and before a regular training stage, into evacuated blood tubes (13 × 100 mm × 6.0 ml BD Vacutainer® Plus plastic serum tube with spray dried clot activator; Becton Dickinson Italia SpA, Milan, Italy). Immediately after blood drawing saliva was also collected from each athlete using saliva sampling devices, which have been validated for measurement of hormones in saliva (Sali‐Tube, DRG instruments GmBH, Marburg, Germany). According to manufacturer's instructions, saliva was released into the device with the help of a piece of straw. All serum and saliva samples were transported to the laboratory of the University Hospital of Parma within 30 min from collection, under controlled conditions of time and temperature. Blood samples were centrifuged according to manufacturer's recommendations (1,300 × g for 10 min at room temperature), and serum was rapidly separated. The Sali‐Tube devices were centrifuged twice at 3,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature, in order to remove particulate material and obtain a clear saliva sample.

Serum cortisol was measured using Beckman Coulter DxI 800 immunoassay system which uses chemiluminescent technology (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA). The total imprecision is reported to be <8.0%. Total testosterone was also measured on Beckman Coulter DxI 800 (Beckman Coulter Inc.). The total imprecision of this assay is reported to be <10%. Free testosterone was calculated from sex hormone‐binding globulin (SHBG) and total testosterone values, as described elsewhere 10. SHBG was measured on Beckman Coulter DxI 800 (Beckman Coulter Inc.), a method displaying a total imprecision <7%. Saliva cortisol was assayed using the conventional Beckman Coulter DxI 800 assay (Beckman Coulter Inc.), a method which has been validated by the manufacturer for measurement of this hormone in saliva. Total testosterone in saliva was also measured on Beckman Coulter DxI 800 (Beckman Coulter Inc.), whereas free testosterone in saliva was assayed using a specific salivary free testosterone enzyme immunoassay (DRG instruments GmBH). The total imprecision of this method is <10%.

The comparison between saliva and serum values was performed by computing Spearman's correlation coefficients, using Analyse‐it (Analyse‐it Software Ltd, Leeds, UK). All subjects provided a written consent for enrollment in the study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

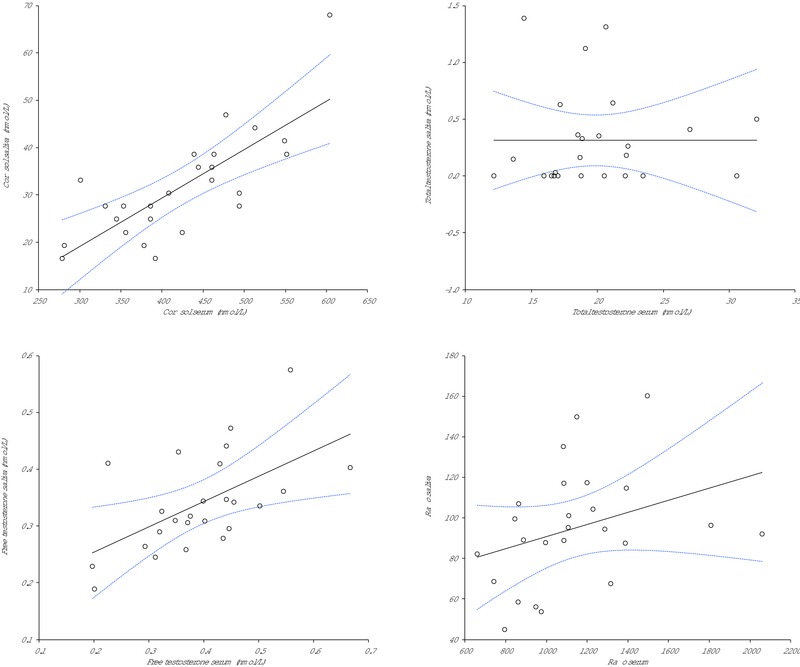

The main demographic characteristic of the study population is shown in Table 1. The ranges (mean and standard deviation) of cortisol, total and free testosterone values as well as the ratio between free testosterone and cortisol in both serum and saliva are shown in Table 2. An excellent correlation was found between serum and saliva cortisol (r = 0.751; P < 0.001). A significant correlation was also observed between free testosterone in serum and saliva (r = 0.590; P = 0.002), whereas no significant correlation was found between total testosterone in serum and saliva (r = 0.181; P = 0.387; Fig. 1). A significant correlation was also found for the free testosterone to cortisol ratio in serum and saliva (r = 0.43; P = 0.031; Fig. 1). Even more importantly, 25/25 (i.e., 100%) of the athletes declared that they would feel more comfortable to have saliva rather than blood periodically collected for long‐term monitoring of physical fitness.

Table 1.

Demographical Variables (Mean and Standard Deviation) of the Study Population, Which Included 25 Member of an Italian Major League Soccer Team

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| n | 25 |

| Age (years) | 27 ± 2 |

| Male (%) | 25 (100%) |

| Height (cm) | 179 ± 4 |

| Body weight (kg) | 68.9 ± 3.8 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.4 ± 1.4 |

| Training (hours/day) | 3.2 ± 1.4 |

Table 2.

Values (Mean and Standard Deviation) of Cortisol, Total Testosterone, Free Testosterone and the Ratio Between Free Testosterone and Cortisol in Paired Serum and Saliva Samples of 25 Member of an Italian Major League Soccer Team

| Parameter | Serum | Saliva |

|---|---|---|

| Cortisol (nmol/l) | 423 ± 86 | 32 ± 11 |

| Total testosterone (nmol/l) | 20 ± 5 | 0.31 ± 0.42 |

| Free testosterone (nmol/l) | 0.39 ± 0.11 | 0.34 ± 0.09 |

| Free testosterone to cortisol ratio (×103) | 0.94 ± 0.24 | 12 ± 4 |

Figure 1.

Spearman's correlation between serum and salivary values of cortisol, total testosterone, free testosterone and the ratio between free testosterone and cortisol (ratio).

DISCUSSION

Monitoring of athlete's performance and physical fitness by means of serum or plasma hormones measurement, especially cortisol and free testosterone, is now considered a mainstay in sports medicine 5, 6. The major drawback of this approach is represented by the need of collecting venous blood, which carries some technical and practical challenges. Although a number of studies have assessed the concentration of both cortisol and free testosterone in saliva of healthy and diseased populations 11, controversial information is available on the correlation between serum and saliva concentration of these hormones in a sport medicine setting.

Obmiński and Stupnicki originally measured the testosterone‐to‐cortisol ratio in a population of triathletes and karate athletes at rest, and reported that salivary and serum values were strongly correlated (r = 0.874; P < 0.001) 12. A significant correlation between baseline values of serum and saliva cortisol has also been observed using two different commercial immunoassays in a population of 25 soccer players 13. Lane and Hackney measured free testosterone values in serum and saliva of 12 endurance‐trained males, observing a highly significant correlation at baseline (r = 0.859; P < 0.001) 14. At variance with these findings, Cadore et al. (15) measured free testosterone and cortisol in resting athletes, and found a significant correlation between serum and saliva cortisol (r = 0.52; P = 0.005), but not between free testosterone in serum and saliva (r = 0.22; P > 0.05). More recently, Hayes et al. measured free testosterone in 15 sedentary males and 20 lifelong exercising males 16, but failed to find a significant correlation between the baseline values in serum and saliva (r = 0.134; P = 0.431).

The results of our investigation attest that the measurement of salivary hormones (i.e., free testosterone, cortisol, and their ratio) with commercial immunoassays may be seen as a valuable perspective for routine and serial monitoring of physical fitness in professional athletes. Indeed, saliva samples can be collected without venipuncture, in difficult environments (e.g., training camps), and this means of collection is more favorably accepted by professional athletes, as convincingly proven in this study. Commercial immunoassays are also easier to perform compared with more time‐consuming and expensive methodologies such as liquid chromatography‐mass spectrometry methods, thus posing a lower organizational burden to clinical laboratories.

REFERENCES

- 1. Reilly T, Ekblom B. The use of recovery methods post‐exercise. J Sports Sci 2005;23:619–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mohr M, Krustrup P, Bangsbo J. Fatigue in soccer: A brief review. J Sports Sci 2005;23:593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Halson SL, Jeukendrup AE. Does overtraining exist? An analysis of overreaching and overtraining research. Sports Med 2004;34:967–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Handziski Z, Maleska V, Petrovska S, et al. The changes of ACTH, cortisol, testosterone and testosterone/cortisol ratio in professional soccer players during a competition half‐season. Bratisl Lek Listy 2006;107:259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Banfi G, Dolci A. Free testosterone/cortisol ratio in soccer: Usefulness of a categorization of values. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2006;46:611–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hug M, Mullis PE, Vogt M, Ventura N, Hoppeler H. Training modalities: Over‐reaching and over‐training in athletes, including a study of the role of hormones. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;17:191–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lippi G, Mattiuzzi C, Banfi G. Controlling sources of preanalytical variability in doping samples: Challenges and solutions. Bioanalysis 2013;5:1571–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Papacosta E, Nassis GP. Saliva as a tool for monitoring steroid, peptide and immune markers in sport and exercise science. J Sci Med Sport 2011;14:424–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lippi G, Mattiuzzi C. Screening for recreational drugs in sports. Balance between fair competition and private life. Perfor Enhan Health 2013;2:72–73. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morris PD, Malkin CJ, Channer KS, Jones TH. A mathematical comparison of techniques to predict biologically available testosterone in a cohort of 1072 men. Eur J Endocrinol 2004;151:241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wood P. Salivary steroid assays—Research or routine? Ann Clin Biochem 2009;46(Pt 3):183–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Obmiński Z, Stupnicki R. Comparison of the testosterone‐to‐cortisol ratio values obtained from hormonal assays in saliva and serum. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1997;37:50–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lippi G, De Vita F, Salvagno GL, Gelati M, Montagnana M, Guidi GC. Measurement of morning saliva cortisol in athletes. Clin Biochem 2009;42:904–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lane AR, Hackney AC. Relationship between salivary and serum testosterone levels in response to different exercise intensities. Hormones 2015;14:258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cadore E, Lhullier F, Brentano M, et al. Correlations between serum and salivary hormonal concentrations in response to resistance exercise. J Sports Sci 2008;26:1067–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hayes LD, Sculthorpe N, Herbert P, et al. Poor levels of agreement between serum and saliva testosterone measurement following exercise training in aging men. Aging Male 2015;18:67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]