Abstract

Objectives

Existing evidence suggests that impaired vitamin D metabolism contribute to the development of atherosclerosis. Aortic intima‐media thickness (IMT) is an earlier marker than carotid IMT of preclinical atherosclerosis. However, there is a lack of researches on direct investigation of relevance between serum 25‐hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) and thoracic aortic IMT. In this study, we aimed to assess the relationship between thoracic aortic IMT and 25(OH)D.

Methods

We studied 117 patients (mean age: 45.5 ± 8.4 years) who underwent transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) for various indications. Serum 25(OH)D was measured using a direct competitive chemiluminescent immunoassay. The patients were divided into three groups according to the their serum 25(OH)D levels (VitDdeficiency, VitDinsufficient and VitDnormal groups). TEE was performed in all subjects. High sensitive C‐reactive protein (hsCRP) and other biochemical markers were measured using an automated chemistry analyzer.

Results

Only 24.8% (29 patients) of patients had normal levels of 25(OH)D. The highest aortic IMT values were observed in VitDdeficiency group compared with VitDinsufficient and VitDnormal groups (P < 0.05, for all). Also aortic IMT values of VitDinsufficient group were higher than VitDnormal group (P < 0.05). 25(OH)D was independently associated with hs‐CRP (β = −0.442, P < 0.001) and aortic IMT (β = −0.499, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

The lower 25(OH)D level was independently associated with higher aortic IMT values. Therefore, hypovitaminosis D may have a role on pathogenesis of subclinical thoracic atherosclerosis.

Keywords: Vitamin D, intima‐media, CRP, echocardiography

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency are now recognized as a global problem, affecting a large percentage of the general population 1. A growing evidence shows that populations who are deficient in 25‐hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) have higher risks for several cardiovascular‐related disorders such as diabetes mellitus 2, obesity 3, hypertension 4, carotid arterial disease 5, impaired arterial stiffness 6, myocardial infarction 7, heart failure 8, and ultimately mortality 9. Previous studies showed that vitamin D deficiency affects vascular function by augmenting atherosclerosis, while treatment with vitamin D is protective 10. Also, recent studies have indicated that 25(OH)D is involved in the pathophysiologic process of atherosclerosis 11.

Although there have been numerous studies on the association between serum 25(OH)D and the diseases of cardiovascular system 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 in the recently, there is lack of researches on direct investigation of relevance between serum 25(OH)D and thoracic aortic intima media thickness (IMT). Whereas, aortic atherosclerotic lesions detected on transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) are markers of diffuse atherosclerotic disease 12, 13 and thoracic aortic IMT has been reported as an earlier marker of preclinical atherosclerosis than carotid IMT14.

The association between thoracic aortic IMT and serum 25(OH)D level remains to be investigated in humans. Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to assess the relationship between thoracic aortic IMT and serum 25(OH)D level in patients undergoing TEE examination for various indications.

METHODS

Study Populations

Between June 2012 and June 2013 we evaluated 117 patients who had non‐atherosclerotic heart disease and underwent TEE examination for various indications (67 male, 50 female and mean age; 41.6 ± 11.3 years) such as evaluation and management of lone atrial fibrillation (26 patients), valvular heart disease (ten patients for mitral valve disease, seven patients for bicuspid aortic valve) and suspected atrial septal defect (74 patients). The patients were classified into three groups according to serum 25(OH)D levels15: VitDdeficiency group (<20 ng/ml, n = 80), VitDinsufficient group (<30 ng/ml and ≥20 ng/ml, n = 56) and VitDnormal group (≥30 ng/ml, n = 29). One hundred and seventy of 413 patients who underwent TEE examination within one year were included in the study. Eighty‐five patients with known coronary artery disease (positive history or clinical signs of ischemic heart disease), peripheral vascular disease, carotid artery surgery, or stroke, and 120 patients who had hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and smokers were excluded from the study. We also excluded 47 patients with familial hypercholesterolemia, aortic dissection or aortic aneurysm, aortic regurgitation, aortic stenosis, as well as 44 patients with poor ultrasonographic recording quality with no clear delineation of the intima‐media complex. In addition, patients taking any medication and positive exercise treadmill test were also excluded from the study. Institutional ethics committee approved the study and written informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from all individuals. Age and gender were recorded. Body mass index (BMI) was computed as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2).

Blood Sampling

Blood samples were obtained following an overnight fasting state just before TEE examination. Blood samples were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min for plasma separation. Plasma samples were stored at −70°C for the analysis of serum 25(OH)D, high sensitive C‐reactive protein (hsCRP), triglyceride, total cholesterol, low‐density lipoprotein (LDL), high‐density lipoprotein (HDL), creatinine, and fasting glucose.

Hs‐CRP was measured with an autoanalyzer (Aeroset) by using a commercial spectrophotometric kit (Scil Diagnostics GmbH, Viernheim, Germany). Serum calcium (8.2–10.2 mg/dl) and parathyroid hormone levels were measured in all subject.

Serum 25(OH)D was measured using a direct competitive chemiluminescent immunoassay (Elecsys; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Within‐run coefficient of variation (CV) was 7.6–11.3% and total imprecision CV was 6.9–10.1%.

Transthoracic and Transesophageal Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography and TEE were performed in all study subjects by using a commercially available system (Vivid 7®, GE Medical Systems, Horten, Norway). Left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) was determined by modified Simpson's method 16. All patients underwent TEE by using a 5Mhz multiplane transesophageal transducer after a 4‐h fasting period prior to the procedure. Subjects were placed in left decubitus with the left arm under the head, which was kept in a flexed position after oropharyngeal anesthesia with lidocaine spray. The transducer was introduced for visualization of the cardiac and aortic structures into the esophagus and gastric cavity through the mouth. An experienced cardiologist blinded to other laboratory results performed TEE. TEE was well tolerated by all patients, and there were no complications. All studies were recorded and were interpreted independently by an experienced observer.

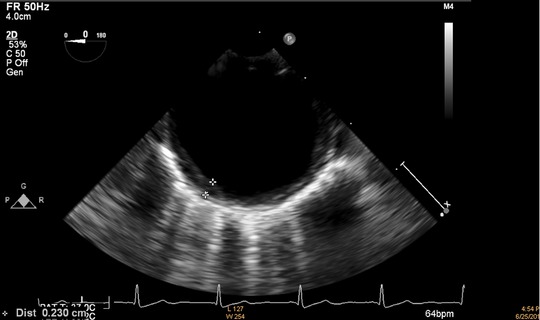

Thoracic aortic IMT was defined as the distance from the leading edge of the lumen‐intima interface to the leading edge of the media–adventitia interface of the far wall. The measurement of IMT in the thoracic aorta was made manually in six separate segments (length of 1 segment 5 cm): ascending aorta, arch, from 0 to 5 cm distal to the arch, from 5 to 10 cm distal to the arch, from 10 to 15 cm distal to the arch, and from 15 to 20 cm distal to the arch. The maximum IMT was measured in each segment and the mean value for the maximum IMT among the 6 segments was taken as the evaluable IMT of the thoracic aorta 17. The sample measurement of thoracic aortic IMT was showed in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The sample measurement of thoracic aortic intima media thickness.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS for Windows 17.0, Chicago, IL, USA). Comparison of categorical variables between the groups was performed using the chi‐square test. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used in the analysis of continuous variables. Analysis of normality was performed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. A stratified post hoc analysis of echocardiographic, clinical, and laboratory variables were performed according to serum 25(OH)D levels. The correlations between serum 25(OH)D and aortic IMT, clinical, laboratory parameters were assessed by the Pearson correlation test. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to identify the independent associations of serum 25(OH)D levels. A 2‐tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reproducibility

Aortic IMT measurements were repeated by the second observer and interobserver variability was calculated as the difference in two measurements of the thirty patient by observer divided by the mean value. Interobserver variability's were 8.6%.

RESULTS

Mean vitamin D value was 24.8 ± 9.9 ng/ml; deficient and insufficient 25(OH)D levels were observed at 40.2% (n = 47) and 35.0% (n = 41) in patients, respectively. Serum 25(OH)D level was normal at only 24.8% (n = 29) of patients.

Baseline Characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Comparison of Baseline, Laboratory, Echocardiographic, and Clinical Characteristics

| VitDdeficiency | VitDinsufficient | VitDnormal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | group (n = 47) | group (n = 41) | group (n = 29) | P‐value |

| Baseline Characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 43.5 ± 12.2 | 39.0 ± 9.6 | 42.3 ± 11.7 | 0.176 |

| Gender (male)X,% | 26 (55.3%) | 24 (58.5%) | 17 (58.6%) | 0.758 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.0 ± 3.8 | 24.4 ± 2.3 | 24.0 ± 3.2 | 0.344 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 111.7 ± 13.0 | 110.4 ± 13.8 | 111.1 ± 11.9 | 0.884 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 70.3 ± 8.9 | 69.0 ± 8.4 | 67.4 ± 8.0 | 0.343 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 78.2 ± 5.3 | 77.9 ± 6.1 | 78.4 ± 7.3 | 0.447 |

| Smoking, %(n) | 12 (25.5%) | 11 (26.8%) | 8 (27.6%) | 0.839 |

| Laboratory Findings | ||||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 86.6 ± 12.0 | 90.4 ± 8.6 | 90.2 ± 9.1 | 0.157 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 168.1 ± 39.6 | 159.5 ± 37.4 | 158.4 ± 23.4 | 0.304 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 105.7 ± 34.7 | 96.0 ± 19.8 | 94.7 ± 20.0 | 0.133 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 44.7 ± 9.2 | 41.9 ± 13.5 | 48.7 ± 11.7 | 0.055 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 117.8 ± 74.6 | 108.1 ± 55.3 | 77.2 ± 22.1a | 0.014 |

| Creatinin (mg/dl) | 0.71 ± 0.18b | 0.80 ± 0.19 | 0.76 ± 0.14 | 0.041 |

| Hs‐CRP (mg/dl) | 0.63 ± 0.09 | 0.61 ± 0.08 | 0.50 ± 0.08c | <0.001 |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 9.2 ± 0.5 | 9.1 ± 0.4 | 9.2 ± 0.5 | 0.759 |

| Parathyroid hormone (pg/ml) | 63.5 ± 24.0 | 61.8 ± 36.0 | 47.1 ± 11.2d | 0.027 |

| Echocardiographic Findings | ||||

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 61.8 ± 3.8 | 62.6 ± 4.0 | 62.2 ± 3.8 | 0.652 |

| Aortic IMT (mm) | 1.83 ± 0.70e | 1.38 ± 0.37f | 0.99 ± 0.50 | <0.001 |

| Clinical Diagnosis | ||||

| ASD suspicion, n (%)* | 30 (63.8%) | 25 (61.0%) | 19 (65.5%) | 0.922 |

| Atrial Fibrillation, n (%)* | 11 (23.4%) | 8 (19.5%) | 7 (24.1%) | 0.872 |

| Valvular heart disease, n (%)* | 6 (12.8%) | 6 (14.6%) | 5 (17.2%) | 0.865 |

*Chi Square

Abbreviations: VitD; 25‐Hydroxyvitamin D, BMI; body mass index, SBP; systolic blood pressure, DBP; diastolic blood pressure, LDL; low density lipoprotein, HDL; high density lipoprotein, Hs‐CRP; high sensitive C reactive protein, IMT; intima media thickness. Bold indicates statistically significant value.

P = 0.004 vs. VitDdeficiency group, p = 0.032 vs. VitDinsufficient group.

P = 0.012 vs. VitDinsufficient group.

P < 0.001 vs. VitDdeficiency group and P = 0.032 vs. VitDinsufficient group.

P = 0.011 vs. VitDdeficiency group and P = 0.026 vs. VitDinsufficient group.

P < 0.001 vs. VitDinsufficient group and VitDnormal group.

P = 0.004 vs. VitDnormal group.

Triglyceride and creatinine values were different among the groups (P < 0.05, for all). The highest hs‐CRP values were observed in VitDdeficiency group compared with VitDinsufficient and VitDnormal groups (P < 0.05, for all). Moreover, hs‐CRP values of VitDinsufficient group were higher than VitDnormal group (P < 0.05). Parathyroid hormone levels of VitDdeficiency and VitDinsufficient groups were higher than VitDnormal group (P < 0.05, for all).

Thoracic Aortic Intima Media Thickness (Table 1)

The highest aortic IMT values were observed in VitDdeficiency group compared with VitDinsufficient and VitDnormal groups (P < 0.05 for all). Also, aortic IMT values of VitDinsufficient group were higher than VitDnormal group (P < 0.05).

Bivariate and Multivariate Relationships of 25(OH)D

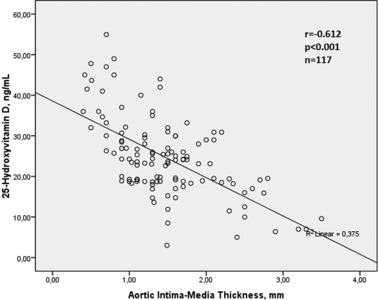

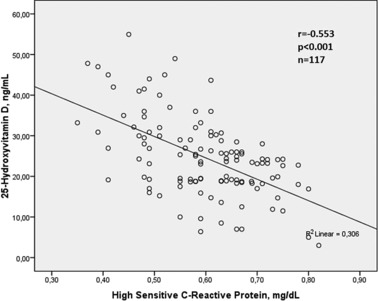

Bivariate and multivariate relationships of 25(OH)D were demonstrated in Table 2. Serum 25(OH)D was found to be associated with BMI (r = −0.315, P = 0.001), LDL cholesterol level (r = −0.187, P = 0.044), triglyceride level (r = −0.227, P = 0.014), hs‐CRP (−0.553, P < 0.001), aortic IMT (r = −0.612, P < 0.001) in bivariate analysis. The relationships between 25(OH)D with aortic IMT and hs‐CRP were shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Multivariate linear regression analysis showed that 25(OH)D was independently related with hs‐CRP (β = −0.442, P < 0.001) and aortic IMT (β = −0.499, P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Bivariate and multivariate relationships of 25(OH)D

| Pearson | Standardized | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| correlation | β regression | |||

| Variables | coefficient | P‐value | coefficients | P‐value |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.315 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.943 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | −0.187 | 0.044 | −0.059 | 0.431 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | −0.227 | 0.014 | −0.018 | 0.808 |

| Hs‐CRP (mg/dl) | −0.553 | <0.001 | −0.442 | <0.001 |

| Aortic IMT (mm) | −0.612 | <0.001 | −0.499 | <0.001 |

Figure 2.

Relationship between 25‐Hydroxyvitamin D level and aortic intima media thickness.

Figure 3.

Relationship between 25‐Hydroxyvitamin D level and high sensitive C reactive protein.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge this is the first study that investigated the relationship between 25(OH)D level and IMT of thoracic aorta in patients without clinical manifestation of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Our results showed that 25(OH)D level is independently associated with extent of IMT of thoracic aorta as well as hs‐CRP.

In addition to its traditional effects on bone health, there is accumulating evidence to suggest that the vitamin D receptor has a broad spectrum of effects on various cell types including the endothelium 18, vascular smooth muscle 19, and cardiomyocytes 20. Vitamin D receptor activation is thought to result in positive effects on cardiovascular system. The relationship between vitamin D insufficiency and coronary atherosclerosis is well known. Several large cross‐sectional and longitudinal observational studies have shown that low levels of 25(OH)D are associated with a increased risk of coronary atherosclerosis 7, 21. In a previous study, Akin et al. reported that low‐serum 25(OH)D level was associated with the severity of coronary atherosclerosis 22. It was shown that levels of 25(OH)D <30 ng/ml were associated with a greater risk of incident myocardial infarction even after adjustment for risk factors known to be associated with coronary artery disease 23.

Carotid IMT by B‐mode ultrasonography has been utilized as a noninvasive surrogate marker to detect the presence, occurrence, and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis 24. Low 25(OH)D level is associated with carotid atherosclerosis assessed with carotid IMT 25. However, Harrington et al. 14 reported that thoracic aortic IMT has been reported as an earlier marker of preclinical atherosclerosis than carotid IMT. Moreover, the negative association between vitamin D levels and the prevalence of peripheral artery disease was confirmed in previous studies 25. An analysis of data from the NHANES has shown a strong negative correlation between low serum 25(OH)D level quartiles and prevalence of peripheral artery disease for each 10 ng/ml decrease in 25(OH)D level 26. On the other hand, the relationship between low 25(OH)D and aortic atherosclerosis assessed with thoracic aortic IMT was not investigated. Present study show that low 25(OH)D level is associated with increased aortic IMT, which reflects subclinical aortic atherosclerosis.

Mechanisms that explain the contribution of low 25(OH)D level to the atherosclerotic process have not been fully clarified. However, several mechanisms may be responsible for this relationship. Vitamin D interacts either directly with the vascular tree or indirectly through its association with cardiovascular risk factors 27. Vitamin D deficiency is viewed as an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis 27. Low levels of 25(OH)D are associated with traditional risk factors such as hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, and diabetes 2, 3, 4, 6, 27 and regulates atherosclerotic biologic pathways 28. On the other hand, vitamin D may play a role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis—through a direct involvement in the process of plaque formation and progression 27, 29. Proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells is a key step for plaque formation in atherosclerotic heart disease 30. Vitamin D modulates key processes in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease including vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation 29. In addition, it was shown that active vitamin D suppresses foam‐cell formation by reducing macrophage cholesterol uptake 31. Lower serum vitamin D levels may facilitate atherosclerosis by increasing macrophage cholesterol uptake. Inflammation is a key factor driving the processes of plaque formation, progression, and rupture in patients with atherosclerotic CAD 32. Vitamin D deficiency promotes stimulation of systemic and vascular inflammation 33. Recent studies have shown an inverse relationship between 25(OH)D levels and hs‐CRP, which reflects to chronic inflammation 6. Present study showed that there was independent inverse relationship between 25(OH)D and hs‐CRP. The relationship between lower serum vitamin D level and increased inflammation may mediate to more severe IMT. Also, the inverse relationships between Vitamin D with vascular calcification, endothelial dysfunction, and arterial stiffness may be effective on aortic atherosclerosis assessed with thoracic aortic IMT 27.

Patients with 25(OH)D deficiency had significantly higher body mass indexes compared to those with sufficient levels of 25(OH)D6, 34. This result supports the findings of the research which demonstrates sequestration of 25(OH)D in adipose tissue which results in decreased amount of circulating 25(OH)D 34. In present study, 25(OH)D was associated with BMI. However, similar relationship was not observed in multivariate regression analysis.

Study Limitations

The present study has some significant limitations: First, the patient population was selected from a diverse population with several disease states, although 25(OH)D was not related to diagnosis of any of these diseases. Second, coronary angiography was not performed in our patients although the diagnosis of coronary artery disease has been excluded according to clinical characteristics and patient history, electrocardiography, and treadmill exercise test. Third, it has been known that serum vitamin D levels vary with region, seasonality, and altitude due to possible effect of sunlight. The half life of vitamin D is approximately 3 weeks, but serum vitamin D levels may change throughout the day and season of the year. Finally, 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D3 is the active metabolite. 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D3 was not measured in present study. However, 25(OH)D has important autocrine and paracrine roles in the synthesis of 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D3 and determining intracellular levels of 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D3 35.

In conclusion, low 25(OH)D is independently associated with higher thoracic aortic IMT as well as hs‐CRP in patients without clinical manifestation of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Low 25(OH)D may play a role on both pathogenesis of subclinical thoracic atherosclerosis and chronic inflammatory process.

REFERENCES

- 1. Norman AW, Bouillon R, Whiting SJ, Vieth R, Lips P. 13th workshop consensus for vitamin D nutritional guidelines. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2007;103:204–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scragg R, Sowers M, Bell C. Serum 25‐hydroxyvitamin D, diabetes, and ethnicity in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Care 2004;27:2813–2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee P, Greenfield JR, Seibel MJ, Eisman JA, Center JR. Adequacy of vitamin D supplementation in severe deficiency is dependent on body mass index. Am J Med 2009;122:1056–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Snijder MB, Lips P, Seidell JC, Visser M, et al. Vitamin D status and parathyroid hormone levels in relation to blood pressure: a population‐based study in older men and women. J Intern Med 2007;261:558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reis JP, von Mühlen D, Michos ED, et al. Serum vitamin D, parathyroid hormone levels, and carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2009;207:585–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kuloglu O, Gür M, Seker T, et al. Serum 25‐hydroxyvitamin D level is associated with aortic distensibility and left ventricle hypertrophy in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2013:DOI: 10.1177/1479164113491125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee JH, Gadi R, Spertus JA, Tang F, O'Keefe JH. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2011;107:1636–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schierbeck LL, Jensen TS, Bang U, et al. Parathyroid hormone and vitamin D—Markers for cardiovascular and all cause mortality in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:626–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dobnig H, Pilz S, Scharnagl H, et al. Independent association of low serum 25‐hydroxyvitamin d and 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D levels with all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1340–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tarcin O, Yavuz DG, Ozben B, et al. Vitamin D improves endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and low vitamin D levels. Diabet Med 2008;25:320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lavie CJ, Lee JH, MIlani RV. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1547–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rohani M, Jogestrand T, Ekberg M, et al. Interrelation between the extent of atherosclerosis in the thoracic aorta, carotid intima—Media thickness and the extent of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2005;179:311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Belhassen L, Carville C, Pelle G, et al. Evaluation of carotid artery and aortic intima—Media thickness measurements for exclusion of significant coronary atherosclerosis in patients scheduled for heart valve surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39: 1139–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harrington J, Peña AS, Gent R, Hirte C, Couper J. Aortic intima media thickness is an early marker of atherosclerosis in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr 2010;156:237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 2007;357:266–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schiller NB, Shah PM, Crawford M, et al. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two‐dimensional echocardiography. American Society of Echocardiography Committee on Standards, Subcommittee on Quantitation of Two‐Dimensional Echocardiograms. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1989;2:358–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nishino M, Masugata H, Yamada Y, et al. Evaluation of thoracic aortic atherosclerosis by transesophageal echocardiography. Am Heart J 1994;127:336–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Merke J, Milde P, Lewicka S, et al. Identification and regulation of 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor activity and biosynthesis of 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D3. Studies in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells and human dermal capillaries. J Clin Invest 1989;83:1903–1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Somjen D, Weisman Y, Kohen F, et al. 25‐hydroxyvitamin D3–1alpha‐hydroxylase is expressed in human vascular smooth muscle cells and is upregulated by parathyroid hormone and estrogenic compounds. Circulation 2005;111:1666–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu‐Wong JR. Potential for vitamin D receptor agonists in the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Br J Pharmacol 2009;158:395–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang TJ, Pencina MJ, Booth SL, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2008;117:503–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Akin F, Ayça B, Köse N, et al. Serum vitamin D levels are independently associated with severity of coronary artery disease. J Investig Med 2012;60:869–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Hollis BW, Rimm EB. 25‐hydroxyvitamin D and risk of myocardial infarction in men: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1174–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nguyen‐Thanh HT, Benzaquen BS. Screening for subclinical coronary artery disease measuring carotid intima media thickness. Am J Cardiol 2009;104:1383–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reis JP, von Mühlen D, Michos ED, et al. Serum vitamin D, parathyroid hormone levels, and carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2009;207:585–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Melamed ML, Muntner P, Michos ED, et al. Serum 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels and the prevalence of peripheral arterial disease: results from NHANES 2001 to 2004. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008;28:1179–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brewer LC, Michos ED, Reis JP. Vitamin D in atherosclerosis, vascular disease, and endothelial function. Curr Drug Targets 2011;12:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Boer IH, Kestenbaum B, Shoben AB, et al. 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels inversely associate with risk for developing coronary artery calcification. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;20:1805–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Artaza JN, Contreras S, Garcia LA, et al. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease: potential role in health disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2011;22:23–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang C. The role of inflammatory cytokines in endothelial dysfunction. Basic Res Cardiol 2008;103:398–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oh J, Weng S, Felton SK, et al. 1,25(OH)2 vitamin d inhibits foam cell formation and suppresses macrophage cholesterol uptake in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2009;120:687–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Libby P. Vascular biology of atherosclerosis: Overview and state of the art. Am J Card 2003;91:3A–6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Etten E, Mathieu C. Immunoregulation by 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D3: Basic concepts. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2005;97:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lin E, Armstrong‐Moore D, Liang Z, et al. Contribution of adipose tissue to plasma 25‐hydroxyvitamin D concentrations during weight loss following gastric bypass surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:588–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oudshoorn C, van der Cammen TJ, McMurdo ME, van Leeuwen JP, Colin EM. Ageing and vitamin D deficiency: Effects on calcium homeostasis and considerations for vitamin D supplementation. Br J Nutr 2009;101:1597–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]