Abstract

Background

The rigorous cytological review by manual or automatic microscopic analysis is critical in the detection of circulating neoplastic cells, since their morphology as well as their count contributes to the diagnosis and prognosis of many diseases. However, the cytological analysis is not always obvious and requires trained and competent cytologist. In this context, the alarms and/or parameters generated by hematology analyzer could be particularly informative to alert the operators.

Methods

Blood samples from patients with Sezary syndrome (n = 9) were studied with Sysmex XN‐1000 analyzer, and compared to patients with benign or tumoral skin lesions (n = 47) and patients with chronic lymphoproliferative B‐cell diseases (n = 51) used as control.

Results

In present series, the value of structural lymphoid parameters (LyX and LyZ) and the alarm Blast/Abn Lympho were statistically higher in Sezary cases than in control cases. In addition, the value of LyX was associated to the count of circulating Sezary cells and value of LyZ to the presence of large Sezary cells, both parameters described as prognostic factors.

Conclusion

The combination of alarm Blast/Abn Lympho and structural parameters (Ly‐X/Ly‐Z/Ly‐Y) may allow to define rule of blood slide review to screen circulating Sezary cells, and give promising results in B‐cell diseases.

Keywords: sezary, diagnosis, morphology, prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Sezary syndrome (SS) is a rare disease, which accounts for less than 5% of all cutaneous T‐cell lymphomas (CTCLs). It occurs in adults, characteristically presents over the age of 60, and has a male predominance. SS is defined by the triad of erythroderma, generalized lymphadenopathy, and the presence of clonally related neoplastic T cells with cerebriform nuclei (Sezary cells) in skin, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood (PB) 1. On the other hand, one or more of the following criteria are required for diagnosis: an absolute Sezary cell count of at least 1 × 109/l, an expanded CD4‐positive T‐cell population resulting in a CD4/CD8 ratio of more than 10 and/or loss of one or more T‐cell antigens 1. The overall survival in patients with SS is markedly decreased compared with patients with other forms of CTCL, with a median of 2.5–5 years. If its prognosis depends on the type and extent of skin lesions and extra cutaneous disease 2, first captured in the TNM classification (based on the size and/or extent (reach) of the primary tumor (T), whether cancer cells have spread to nearby (regional) lymph nodes (N), and whether metastasis (M), or the spread of the cancer to other parts of the body, has occurred) and published for CTCL in 1979 3, it is now clearly established that the evaluation of blood involvement must be added in this nodal clinicopathologic classification 4. Although the assessment of circulating Sezary cells can be made by immunophenotyping by flow cytometry (FCM) and/or molecular analysis, in most hematology laboratory the cytological analysis of blood smears is still the first step to screen circulating Sezary cells. The rigorous cytological review by manual or automatic microscopic analysis is however labor‐intensive and time‐consuming, and requires trained and competent technical staff and biologist. With continuing pressure on laboratory resources, it is furthermore essential to reduce the number of blood films examined without missing important diagnosis information, and to define rules of slide review that would provide an increase in specificity, fewer false‐positive results with no loss of sensitivity or decrease in true‐positive results. In addition, the identification of Sezary cells into blood smears may be difficult in some cases as the morphology can overlap with various reactive or other neoplastic conditions. Therefore, the alarms and/or parameters generated by the hematology analyzer could be particularly informative to alert the operators. Recently, we have reported the pertinence of the parameters obtained by the Sysmex XE‐5000™ (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan) allowing to define rule of slide review in a context of “normal” lymphocyte count 5. The Sysmex XN‐1000™ as the Sysmex XE‐5000™ is an automated hematology analyzer performing the complete blood count: white blood cells (WBCs), red blood cells, and platelets, using fluorescent FCM and hydrodynamic focusing technologies, as well as differentiating six reportable WBC populations. The XN‐1000™ utilizes the new system based on shape recognition instead of conventional discriminators to separate cell populations into well‐defined clusters. With this analyzer, each leukocyte population is here defined in three dimensions by the structural parameters.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the relevance of parameters and/or alarms generated by the XN‐1000™ analyzer to detect circulating neoplastic lymphoid cells, and illustrated here by Sezary cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens

A cohort of nine patients with SS at diagnosis according to the WHO 2008 classification was analyzed. In all cases, the diagnosis was histologically proven by hematopathologist on skin biopsy. Forty‐seven patients from dermatologic department presenting benign or tumoral skin lesions (psoriasis, melanoma, other T‐cell lymphoma…) were used as controls. All PB cases have been routinely studied by morphological and immunological analysis. In addition, in some SS cases (n = 5) molecular analysis to assess for a T‐cell clone in the blood was performed. Freshly made blood films were obtained, and prepared automatically by Sysmex SP‐1000 (Sysmex Corporation) and stained with May–Grunwald–Giemsa. Smears were reviewed and evaluated for cytological features by expert haematologists (LB, DM, PF): a manual 100‐cell differential lymphocyte count was performed with a special attention to Sezary cell, in particular the evaluation of large Sezary cell.

Another cohort of PB samples (n = 51) from patients presenting chronic lymphoproliferative B‐cell disease (CLPD) has been secondly compared to Sezary samples. This cohort was divided into two groups according the WHO 2008 classification: (1) chronic lymphocytic leukemia group (CLL, n = 41) and (2) non‐CLL group (n = 10), including marginal zone lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma.

Methods

Blood counts were performed with the Sysmex XN‐1000™ analyzer. The parameters that have been studied were leukocyte, lymphocyte count, and the different structural parameters (Ly‐X, Ly‐Y, Ly‐Z, Neutro‐X, Neutro‐Y, Neutro‐Z…) as well as the “flag” Blast/Abn Lympho that was generated by the analyzer from structural parameters and “flag” Abn scattergramm. In this article, only the results of pertinent parameter and alarm were discussed. Details of red cell and platelet measurements were not evaluated.

At the same time, whole PB were stained using eight combinations of monoclonal antibodies (MoAb) directly conjugated and then analyzed on a BD FACS Canto II cytometer (BD FACS DIVA software, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). A wide panel of MoAb directed against T‐cell antigen was tested routinely and the major antibodies (CD classification, clone, fluorochrome labeled) used were as follow : CD3 (SK7, APC‐Cy7, Beckman‐Coulter, Hialeah, FL), CD4 (RPA‐T4, V450, Beckman‐Coulter,), CD8 (SK1, AmCyan, Beckman‐Coulter), CD2 (S2, 5, APC, Becton Dickinson), CD7 (8H8, 1, FITC, Beckman‐Coulter), CD5 (L17F12, PercPCy5.5, Beckman‐Coulter), CD26 (L272, PE, Beckman‐Coulter). Methods for immunophenotyping analysis by FCM have been previously reported 6. Briefly at least 10,000 CD3‐positive T lymphocytes were collected for each MoAb combination, and in all eight color the anti‐CD4 was included as one of the antigen studied and allowed the gating of CD4‐positive T cells.

In some cases, molecular study has been performed. DNA was extracted from PB cell suspensions using High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). T‐cell receptor (TCR) γ‐chain gene rearrangements were studied by using a GC‐clamp multiplex PCR‐γ‐DGGE procedure as previously described 7 and the immunoglobulin gene rearrangements by multiplex PCR using consensus primers from European BIOMED‐2 concerted action 8.

Statistics

The Mann–Whitney U‐test (R statistical software version 2.15.1, Microsoft Corporation, USA) was used for the comparisons of the different studied parameters and Spearman test for the correlation between them. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant. Multivariate analysis could not be used since the low number of cases. Data were also analyzed using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis (XLSTAT 2012 software, Microsoft Corporation).

RESULTS

Detection of Neoplastic Cells

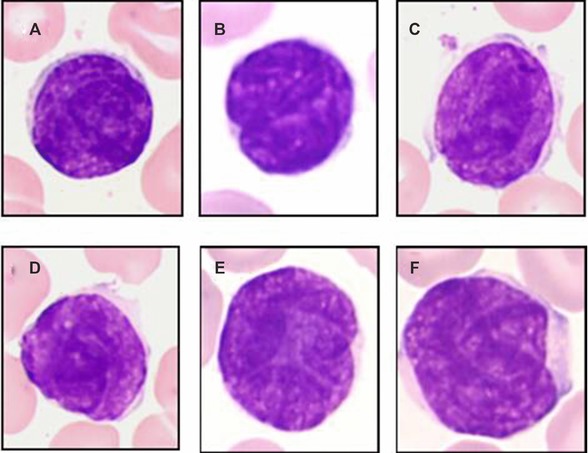

The presence or absence of Sezary cells in PB has been first determined by cytological blood smears analysis, and then confirmed by FCM analysis in all cases as well as TCR rearrangement analysis in some cases (data not shown). By definition, all Sezary cases presented a Sezary cell count above 1 × 109/l (median = 3.6; range 1.0–6.0) in contrast to control group, in which Sezary cells were never detected by cytology and immunology analysis. The cytology of Sezary cells was typical with small to medium cells presenting irregular/convoluted nuclei (defined by histology as cerebriform nuclei) and condensed chromatin. The cytoplasm was moderately abundant with variable basophilia (faint to moderate). In seven cases, a contingent of larger Sezary cells (median = 20% of neoplastic cells; range 4–50%) was detected (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Cytology of Sezary cells. Sezary cells correspond to small to medium cells with irregular/convoluted nuclei (defined by histology as cerebriform) and condensed chromatin. The cytoplasm was moderately abundant with variable basophilia (faint to moderate) (A–D). Occasional larger cells were observed (E, F).

Quantitative and Qualitative Parameters

The values of all parameters obtained by the analyzer were exported and evaluated. The medians were calculated for each parameter and only interesting parameters are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Different Parameters of Sysmex XN‐1000™

| Alarm = Blast/Abn Lympho | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <100 | ≥100 | Ly‐X* | Ly‐Y** | Ly‐Z* | ||

| Sezary cases (n = 9) | 0 | 9 | Mean | 89.90 | 70.00 | 72.60 |

| Range | 88.55–91.22 | 62.60–87.30 | 69.00–73.32 | |||

| Control cases (n = 47) | 29 | 18 | Mean | 82.00 | 69.20 | 62.80 |

| Range | 75.52–88.52 | 62.00–79.30 | 57.80–77.50 | |||

| CLPD (n = 51) | 4 | 37 | Mean | 81.30 | 62.70 | 64.20 |

| CLL (n = 41) | Range | 77.90–82.60 | 58.30–66.10 | 61.80–66.40 | ||

| Non‐CLL (n = 10) | 1 | 9 | Mean | 83.95 | 69.35 | 64.85 |

| Range | 81.85–87.70 | 67.20–75.30 | 62.32–65.32 | |||

CLPD, chronic lymphoproliferative disease; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, non‐CLL including marginal zone B‐cell lymphoma and mantle cell B‐cell lymphoma, when alarm = Blast/Abn Lympho is above 100, Sysmex advises a slide review, *P < 0.05 (Mann–Whitney U‐test): Sezary cases versus control cases and versus CLPD; ** P < 0.05 (Mann–Whitney U‐test): CLL cases versus non‐CLL.

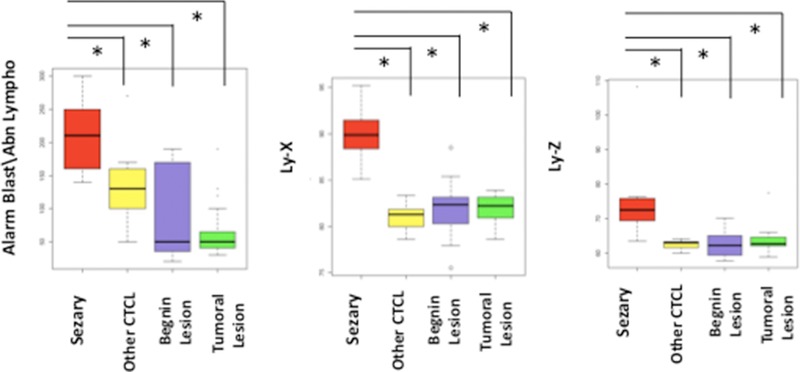

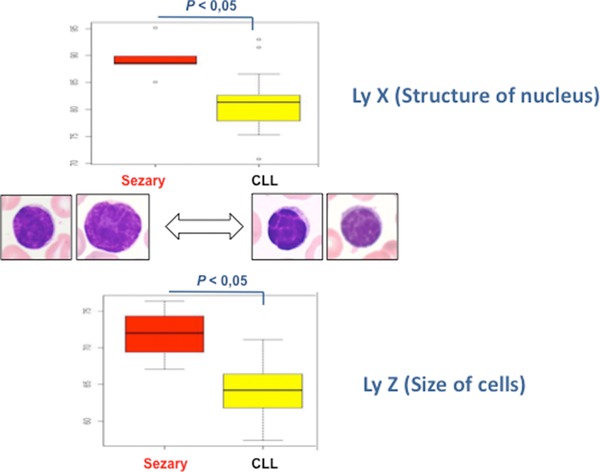

The alarm Blast/Abn Lympho generated by quantitative and structural parameters has been defined by Sysmex as a pertinent “flag” to detect abnormal lymphoid cells: when the value is greater than or equal to 100, Sysmex advises to trigger slide review. We showed here that the value of this “flag” is influenced by the lymphocyte count (data not shown) and samples with increased lymphocyte count in particular above 5 × 109/l, were almost positive (“flag” ≥ 100). Here the lymphocyte count was not statistically different in Sezary group than in control group. However, all Sezary cases showed a positive “flag” Blast/Abn Lympho (≥100), in contrast to control group (18/47) (Table 1). Thus, the positivity of “flag” Blast/Abn Lympho in Sezary group suggested the presence of abnormal circulating lymphoid cells and should trigger the slide review to screen Sezary cells. The analyzer generates the qualitative alarm Abn Scattergramm when the lymphocyte population cannot be clearly distinguished from the monocyte population. In most Sezary cases (6/9) this “flag” was positive, although all cases but one were negative in control group. The value of Ly‐X and Ly‐Z parameters was statistically higher in Sezary group than in control group (Table 1, Fig. 2), although the Ly‐Y value was not statistically different.

Figure 2.

Alarm Blast/Abn Lympho and structural parameters (Ly‐X and Ly‐Z). Sezary cases presented statistically higher value of the alarm Blast/Abn Lympho, Ly‐X, and Ly‐Z than control cases including reactive skin lesion, other cutaneous T‐cell lymphomas (except mycosis fungoides), malignant dermatologic lesion such as melanoma.*P < 0.05 (Mann–Whitney U‐test).

Determination of Discriminative Parameters

Using the method of area under the ROC curve (AUC) and ROC curve analysis, discriminative threshold have been determined (Table 2). In the present series, a Ly‐X threshold above or equal to 85 should trigger a slide review to screen Sezary cells (sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 94%) as well as a Ly‐Z threshold above or equal to 67 (sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 94%).

Table 2.

Discriminative Thresholds of Alarm and Parameters

| Alarm: Blast/Abn Lympho | Ly‐X | Ly‐Z | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <100 | ≥100 | <85 | ≥85 | <67 | ≥67 | |

| Sezary cases (n = 9) | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 8 |

| Control cases (n = 47) | 29 | 18 | 44 | 3 | 44 | 3 |

| CLPD (n = 51) | ||||||

| CLL (n = 41) | 4 | 37 | 39 | 2 | 33 | 8 |

| Non‐CLL (n = 10) | 1 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 1 |

CLPD, chronic lymphoproliferative disease; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, non‐CLL including marginal zone B‐cell lymphoma and mantle cell B‐cell lymphoma.

Threshold of 100 (alarm) is given by Sysmex, threshold of 85 (Ly‐X) and 67 (Ly‐Z) have been determined by the AUC and ROC curve analysis.

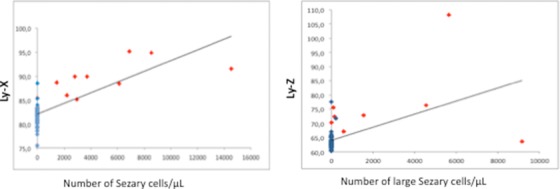

Relation between Structural Parameters and the Morphology

Interestingly, the parameter Ly‐X (influenced by the nuclei structure and chromatin) was correlated to the number of neoplastic cells, and the parameter Ly‐Z that is defined by the size of the cells tended to be correlated to the presence of large Sezary cells (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Correlation between structural parameters and morphology. Structural parameters LyX and LyZ tended to be correlated to number of Sezary cells and number of large Sezary cells, respectively (P < 0.05; Spearman test).

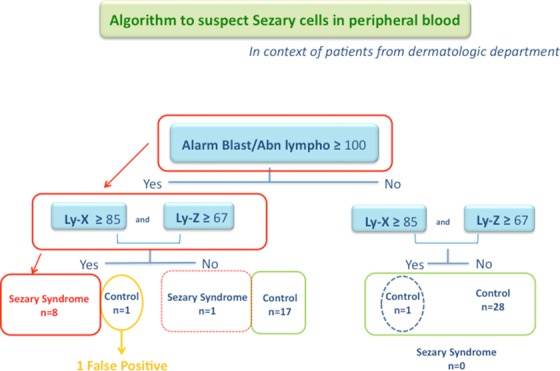

Determination of Rule of Slide Review to Screen Circulating Sezary Cells

Thus in a context of patient with dermatologic lesion and suspicion of SS from present results and when Blast/Abn Lympho “flag” is over or equal the threshold of 100, it seemed justified to establish an additional rule of slide review integrating both parameters (Ly‐X and Ly‐Z), since 18 control cases showed a “flag” above or equal 100. Combining previous thresholds (“flag” Blast/Abn Lympho ≥ 100, Ly‐X ≥ 85, Ly‐Z ≥ 67), criteria ordering slide review have been defined (Table 3, Fig. 4). The algorithm integrating these three criteria allowed predicting the presence of circulating Sezary cells without excessive false‐positive cases (one case) and with only one false‐negative case. In control group, only two cases presented the criteria (Ly‐X ≥ 85, Ly‐Z ≥ 67): one with the “flag” Blast/Abn Lymph above 100 and the other with the “flag” to 40. The relevance of this rule requires now validation in a larger Sezary cohort.

Table 3.

Rule of Slide Review

| Alarm = Blast/Abn Lympho ≥ 100 and Ly‐X ≥ 85 and Ly‐Z ≥ 67 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Sezary cases (n = 9) | 8 | 1 |

| Control cases (n = 47) | 1 | 46 |

| CLPD (n = 51) | ||

| CLL (n = 41) | 2 | 39 |

| Non‐CLL (n = 10) | 1 | 9 |

CLPD, chronic lymphoproliferative disease; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, non‐CLL including marginal zone B‐cell lymphoma and mantle cell B‐cell lymphoma.

The threshold of alarm is given by Sysmex, and threshold of Ly‐X and Ly‐Z have been determined by the ROC and AUC.

Figure 4.

Algorithm to define slide review to screen Sezary cells in context of skin lesion.

Validation of the Results in Cohort of Hematologic B‐Cell Neoplasms

The alarm and parameters obtained in the present Sezary cases were then compared to a series of CLPD (CLL and non‐CLL). As expected, most CLPD cases showed a positive alarm Blast/Abn Lympho (≥100: 46/51) (Table 1), since all CLPD cases have been selected to have neoplastic circulating B cells. Interestingly, the value of Ly‐X and Ly‐Z were statistically higher in Sezary cases than in CLPD cases (Table 2, Fig. 5) and allow discriminating CLPD cases from Sezary cases, when the “flag” Blast/Abn Lympho was positive. On the other hand, this allows validating our previous algorithm in an independent series of CLPD with only three false positive (Blast/Abn Lympho ≥ 100, Ly‐X ≥ 85, and Ly‐Z ≥ 67) (Table 3). On the other hand among B‐cell disorders, Ly‐Y was statistically lower in CLL than in non‐CLL (Table 1). Therefore, if the Ly‐Y parameter was not relevant to discriminate Sezary cases from other reactive or malignant cases of patients with skin lesion, and in particular in the detection of circulating Sezary cells, it seems to be pertinent in B‐cell neoplasm characterization.

Figure 5.

Alarm Blast/Abn Lympho and structural parameters (Ly‐X, Ly‐Y, and Ly‐Z). Sezary cases presented statistically higher value of Ly‐X and Ly‐Z than CLPD cases including CLL and non‐CLL, in contrast no significant difference was observed for alarm Blast/Abn Lympho and Ly‐Y between both groups. *P < 0.05 (Mann–Whitney U‐test). Among B‐CLPD, CLL cases presented lower value of Ly‐X and Ly‐Y than non‐CLL cases, and no statistically difference for Ly‐Z. # P < 0.05 (Mann–Whitney U‐test).

In addition, the statistical difference of the value Ly‐X and Ly‐Z between CLL and Sezary cases was consistent to the definition of these parameters, and the morphology of neoplastic cells. Indeed, CLL cells correspond to small cell with regular nuclei, clumped chromatin, in contrast to Sezary cells that correspond to small to medium cell, with irregular nuclei and condensed chromatin (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Relation between cytology and structural parameters. Ly‐X defined by the structure of nuclei and chromatin is statistically higher in Sezary cells (cerebriform nuclei) than in CLL cells (regular nuclei). Ly‐Z defined by the size of cells is statistically higher in Sezary cells (small to medium cells and occasionally large cells) than in CLL cells (small cells).

DISCUSSION

One of the main criteria needed for Sezary diagnosis is the detection of circulating Sezary cells 1. The quantification of these circulating neoplastic T cells is particularly critical, since the level of blood involvement is now integrated in the TNM classification of SS. An important Sezary cell count in PB is now definitely associated with poor outcome 9. If the study of TCR rearrangement by PCR is the robust analysis to confirm circulating T‐cell clone and its relation to the clone detected in skin lesion and/or lymph node, the PCR is unfortunately a qualitative analysis that cannot quantify circulating Sezary cell. The alternative analysis to confirm PB involvement is the immunological analysis by FCM. The Sezary cells present indeed a characteristic immunological profile such as loss of the CD7 and/or CD26 T‐cell markers that allows usually to detect and to quantify circulating Sezary cells 10, 11, 12, 13. On the other hand, the CD158k expression or the loss of the CD26 by Sezary cells has a prognostic significance 14, 15. Therefore, the immunophenotyping by FCM becomes a major diagnostic and prognostic tool in SS. However, the FCM analysis is relatively expensive and the pertinent choice of a panel of specific antibodies rather than a large panel of antibodies is therefore required and should be oriented by cytological analysis. Though it is evident that cytological analysis is less objective, quantifiable, and reproducible to identify and track blood involvement by Sezary cells. Moreover, the cerebriform nuclear morphology that characterizes Sezary cells is not entirely specific for neoplastic T cells 16, and the number of neoplastic cells determined by cytology may be often underestimated compared to FCM, in particular by non experimented technical staff 17. Thus the data obtained by hematology analyzer could be particularly informative to alert the operators and to trigger slide review in order to screen carefully Sezary cells. As previously reported with the SYSMEX XE‐5000™ analyzer 5, we demonstrate here the pertinence of the data generated by the Sysmex XN‐1000™ analyzer. Among the different parameters provided by this analyzer, the combination of alarm Blast/Abn Lympho with the values of the parameters Ly‐X and Ly‐Z, routinely available appears particularly informative to trigger slide review and should lead to screen Sezary cells in a context of skin lesion suspect of SS. The use of present algorithm (“flag” Blast/Abn Lympho ≥ 100, Ly‐X ≥ 85, Ly‐Z ≥ 67) may have many consequences: the reduction of technical staff time at the microscope together with an increase in the efficiency of complementary analyses requests, and optimization of time and quality of blood smears analysis. In addition, a significant cost reduction of analysis could be obtained by decreasing 1 the number of blood smear, and 2 the number of complementary analyses especially immunophenotyping by FCM. In addition to alert the operators of circulating Sezary cells, the value of the structural parameters (Ly‐X, Ly‐Z) may allow to identify and quantify the larger Sezary cell, and constitute so a useful help in the determination of large cells as prognostic factor. It will be interesting to test this rule in the follow‐up of patients with Sezary and to know if it could be suitable to monitor circulating tumor cell load during therapy. Finally, it is essential to confirm our algorithm among large series including specimens of patients with Sezary (at diagnosis and follow‐up) and patients with other hematology neoplasia, since it appears also pertinent to discriminate PB with circulating Sezary cells from PB with circulating cells of CLPD. The promising results observed in B‐cell neoplasms with our algorithm should be now assessed comprising other parameters such as the Ly‐Y. Indeed, we reported here that the parameter Ly‐Y seems be crucial in B‐cell disorders in contrast to the results obtained in Sezary cohort. In association to the alarm Blast/Abn Lympho ≥ 100, both parameters Ly‐X and Ly‐Y may be indeed certainly helpful to distinguish CLL from non‐CLL. A specific rule for B‐cell disorders may so orientate the diagnosis in cases where morphology, immunology, and/or karyotype are not informative. Obviously these first data must be confirmed on a larger CLPD cohort.

In conclusion, the alarm Blast/Abn Lympho and structural parameters of lymphoid cells (Ly‐X, Ly‐Z, Ly‐Y) generated by the Sysmex XN‐1000™ analyzer appears particularly informative in the qualitative and quantitative analysis of lymphoid cells, and allow to define rule of slide review to screen circulating neoplastic cells of lymphoid neoplasm. Therefore, the data generated by this analyzer may become a useful help for the diagnosis and prognosis of SS allowing the evaluation of the circulating tumoral burden and give also promising results in lymphoid B‐cell neoplasms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge M. JP Perol from Sysmex Europe for his continuous support and help with statistical issues.

REFERENCES

- 1. Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris N, et al. In: Jaffe E, Pileri S, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman J. (Eds.), World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, fourth edition. Lyon, France: IARC; WHO Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kim YH, Liu HL, Mraz‐Gernhard S, et al. Long‐term outcome of 525 patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: Clinical prognostic factors and risk for disease progression. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:857–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bunn P, Lamberg S. Report of the committee on staging and classification of cutaneous T‐cell lymphomas. Cancer Treat Rep 1979;63:725–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, et al. Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: A proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood 2007;110:1713–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chhuy J, Morel D, Goeddert G, et al. Pertinence of the Sysmex XE‐5000™ parameters: Rule of slide review in a context of ‘normal’ lymphocyte count (defined from control and mantle cell lymphoma blood specimens). Int J Lab Hematol 2013;35:510–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baseggio L, Berger F, Morel D, et al. Identification of circulating CD10 positive T cells in angioimmunoblastic T‐cell lymphoma. Leukemia 2006;20:296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Theodorou I, Bigorgne C, Delfau M H, et al. VJ rearrangements of the TCR locus in peripheral T‐cell lymphomas: Analysis by polymerase chain reaction and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. J Pathol 1996;178:303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brüggemann M, White H, Gaulard P, et al. Powerful strategy for polymerase chain reaction‐based clonality assessment in T‐cell malignancies report of the BIOMED‐2 concerted action BHM4 CT98–3936. Leukemia 2007;21:215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosen ST, Querfeld C. Primary cutaneous T‐cell lymphomas. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2006;513:323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harmon CB, Witzig TE, Katzmann JA, et al. Detection of circulating T cells with CD4+CD7‐ immunophenotype in patients with benign and malignant lymphoproliferative dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;35:404–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rappl G, Muche JM, Abken H, et al. CD4(+)CD7(‐) T cells compose the dominant T‐cell clone in the peripheral blood of patients with Sézary syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:456–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bernengo MG, Novelli M, Quaglino P, et al. The relevance of the CD4+ CD26‐ subset in the identification of circulating Sézary cells. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:125–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scala E, Narducci MG, Amerio P, et al. T cell receptor‐Vbeta analysis identifies a dominant CD60+CD26‐ CD49d‐ T cell clone in the peripheral blood of Sézary syndrome patients. J Invest Dermatol 2002;119:193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Poszepczynska‐Guigné E, Schiavon V, D'Incan M, et al. CD158k/KIR3DL2 is a new phenotypic marker of Sezary cells: Relevance for the diagnosis and follow‐up of Sezary syndrome. J Invest Dermatol 2004;122:820–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vonderheid EC, Bernengo MG. The Sézary syndrome: Hematologic criteria. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2003;17:1367–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vonderheid EC, Bernengo MG, Burg G, et al. Update on erythrodermic cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma: Report of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46:95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bogen SA, Pelley D, Charif M, et al. Immunophenotypic identification of Sézary cells in peripheral blood. Am J Clin Pathol 1996;106:739–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]