A 76-year-old man with previous history of kidney transplantation in 2003 (due to chronic kidney injury of unknown etiology), arterial hypertension and a thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm was admitted to our center for a thoracic endovascular repair. His usual medication was tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, prednisolone, captopril and carvedilol. After surgery the patient was referred for an abdominal computed tomography (CT) due to epigastric pain and vomiting with associated hemoglobin drop to 8g/dl (from a previous value of 14g/dl). CT scan revealed a massive retroperitoneal hematoma (12×6.5cm). Blood transfusions were undertaken and due to iron deficiency anemia, oral ferrous sulfate was initiated.

One week later, the patient was referred for an upper endoscopy due to dysphagia.

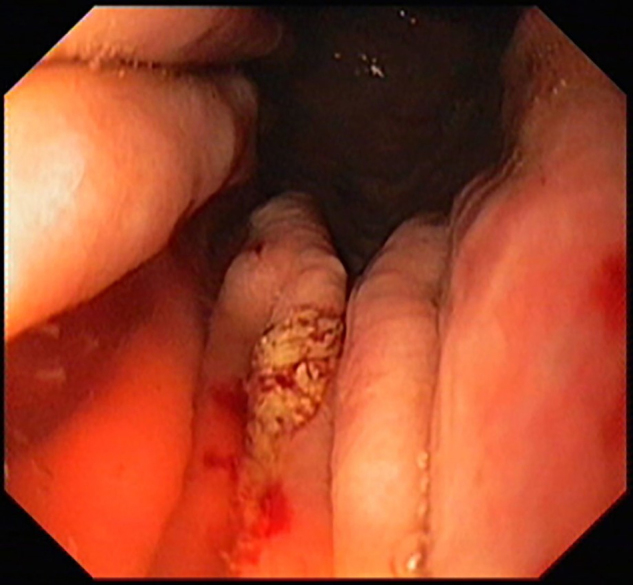

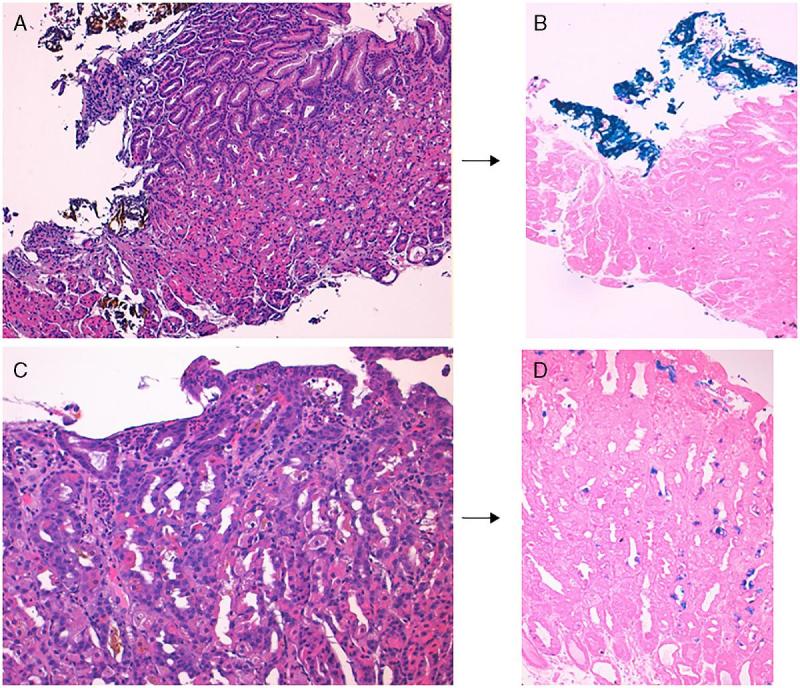

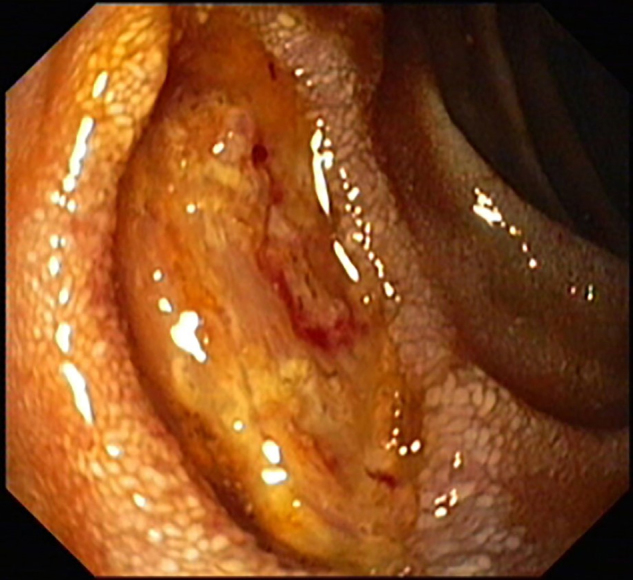

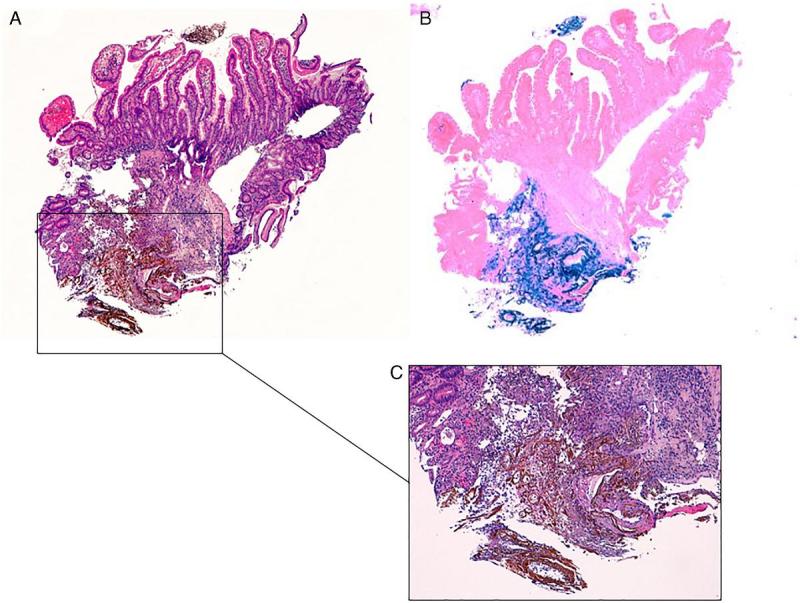

Upper endoscopy did not show esophageal lesions; however multiple erosions in the gastric body were detected (Fig. 1) with biopsies revealing extracellular crystalline iron deposition the superficial lamina propria beneath eroded epithelium and in the lumen of the gastric glands, with some focal intracellular granular iron deposition in glandular cells, confirmed by Perls' iron (Prussian blue) stain (Fig. 2). In the upper endoscopy was also evident a 12mm ulcer with clean base in the anterior wall of the second part of duodenum (Fig. 3). Biopsies of duodenal mucosa revealed an area of ulceration with extracellular crystalline and fibrillar iron deposition (Perls' positive) over granulation tissue associated with foreign body reaction (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Erosion in the gastric body.

Fig. 2.

Gastric mucosa with iron deposition. Gastric biopsy specimen showing extracellular brown crystalline iron deposition over eroded epithelium (A, H&E stain, 100×), highlighted by Perls' iron (Prussian blue) stain (B, 100×). In some areas there was intracellular brown granular iron deposition within glandular epithelium (C, H&E stain, 200×), highlighted by Perls' stain (D, 100×).

Fig. 3.

Ulcer in the second part of duodenum.

Fig. 4.

Duodenal mucosa with iron deposition. (A–C) Duodenal ulcer showing extracellular brown crystalline and fibrillar iron deposition over granulation tissue (H&E stain, 40× in A and 100× in C), highlighted by Perls' stain, 40× (B).

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection was ruled out after negative results in the immunohistochemical and molecular biology analysis. Also Helicobacter pylori infection was not found with Giemsa stain study.

Oral ferrous sulfate is commonly used to treat iron deficiency anemia. Iron pill-induced gastroduodenopathy is a possible, but rarely described complication of oral iron supplementation. However it is likely that its exact prevalence is largely underestimated. Abraham et al. reported a prevalence of focal erosive mucosa injury from iron therapy in 0.7% of gastrointestinal biopsies.1 Kaye et al. also prospectively evaluated the effects of iron supplementation on patients with iron deficiency anemia and encountered visible erosions in 6 of the 16 patients with confirmed iron deposition on biopsy, a considerable higher proportion when compared to patients without iron supplementation (14/141).2

Histologically, iron deposition in the upper gastrointestinal tract can occur in three distinctive patterns, as described by Marginean et al.3,4,5 Type A (“nonspecific”) pattern is characterized by intracellular iron deposition in macrophages, stromal and epithelium. It is frequently associated with mucosal inflammation and may represent iron deposition from prior mucosal hemorrhage. Type B (“iron-pill induced mucosal injury”) pattern is characterized mostly by extracellular deposition and focally, by intracellular deposition in blood vessels, macrophages, and epithelium. This type is typically associated with oral iron-containing medications. In this type iron deposition may be associated with fibrosis, inflammation, and foreign body reaction. In the type C (“glandular siderosis”) pattern there is diffuse iron deposition predominantly in deeper glands of the mucosa. It is often associated with systemic iron overload or hemochromatosis.

In our case, the iron deposition in both gastric and duodenal mucosa fit in the pattern B, suggesting that the mucosal injury was probably triggered by the oral ferrous sulfate intake.

However, since the patient had multiple comorbidities it is impossible to know if ferrous sulfate was the main responsible or exacerbated previously induced gastroduodenal ulceration.

Reports of iron-induced gastroduodenal mucosal injury with endoscopic and histologic evidence are scarce. Histology is essential to render this diagnosis. In the presence of ulcers with atypical location or with suspicious endoscopic findings, biopsies should always be obtained. If this condition is suspected, iron pills should be suspended and iron should be administered intravenously.6

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Available online 17 June 2017

References

- 1.Abraham SC, Yardley JH, Wu TT. Erosive injury to the upper gastrointestinal tract in patients receiving iron medication: an under recognized entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1241-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaye P, Abdulla K, Wood J, James P, Foley S, Ragunath K, et al. Iron-induced mucosal pathology of the upper gastrointestinal tract: a common finding in patients on oral iron therapy. Histopathology. 2008;53:311-317. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marginean EC, Bennick M, Cyczk J, Robert ME, Jain D. Gastric siderosis: patterns and significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:514-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kothadia JP, Arju R, Kaminski M, Mahmud A, Chow J, Giashuddin S. Gastric siderosis: an under-recognized and rare clinical entity. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:1-8. 10.1177/2050312116632109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kothadia JP, Kaminski M, Giashuddin S. Duodenal siderosis: a rare clinical finding in a patient with duodenal inflammation. Ann Gastroenterol. 2016;29:379 10.20524/aog.2016.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Areia M, Gradiz R, Souto P, Camacho E, Silva MR, Almeida N, et al. Iron-induced esophageal ulceration. Endoscopy. 2007;39:E326 10.1055/s-2007-966820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]