ABSTRACT

Concentrated global attention is needed on the long-term epidemics of infectious diseases, such as HIV, tuberculosis (TB), malaria, hepatitis and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), which require a magnified response sustained over a long period to bring them to an end. Building on the progress made towards the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a joint global public health approach to accelerate progress and meet the ambitious global targets set for 2030 for HIV, TB, malaria, hepatitis and NTDs in the era of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Drawing on the common elements of the individual disease strategies, the new approach provides opportunities for joint and synergistic efforts. The framework emphasizes key actions including expansion of universal health coverage (UHC), ensuring equity and respect for human rights, establishment of a new approach to strategic information within and beyond health, strengthening of health systems with integrated delivery of interventions, pursue of sustainable financing, and promotion of research across the spectrum from product development to implementation research.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, Malaria, Neglected tropical diseases, Hepatitis, Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction

In the new millennium, epidemics of SARS, influenza, Ebola and Zika have concentrated global attention on infectious disease outbreaks and the acute response needed to bring them to an end. However, much more focused attention is also needed on the long-term endemic infectious diseases such as tuberculosis (TB), HIV, malaria, hepatitis and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). These diseases are estimated to have caused, together, about 4.3 million deaths in 2015, i.e., nearly 12,000 deaths every day. This represents 8% of deaths worldwide.1 They remain a wide-reaching concern in global health on account of the mortality burden and economic impact. Many of these infectious diseases, often concentrated among the poorest populations in the world, including in high-income settings, also cause chronic illness, disability, sequelae, stigma and exclusion from society. Bringing them to an end requires a magnified and sustained decade-long response.

A new global public health approach in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) era

The United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),2 established by all nations to pursue development in all countries of the world, represent a unique opportunity to reconsider approaches to health, including to endemic, long-standing infectious diseases. The principles of the SDGs incorporate a universal, globally applicable, quest of peace, prosperity, economic progress, and equity and social justice for all people. They foresee a much increased investments on development through both domestic and aid-related financing. Its 17 goals (and 169 targets) are considered integrated and indivisible, therefore promoting a multisectoral approach towards solutions. This multidisciplinary approach applies well to health, which is determined by multiple factors that often are not addressed within the health sector alone and require necessarily collaboration and partnership with different sectors. SDG3, “Ensure health lives and promote well-being for all at all ages”, includes target 3.3 calling to “End the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne and other communicable diseases”. This target, set for 2030, is very ambitious, but the hope is that it may stimulate more rapid investments and efforts towards the control and, ultimately, the elimination of the human scourge represented by those infectious diseases.

Since many features are common in the response to the endemic infectious diseases, the World Health Organization (WHO) promotes a coherent and joint public health approach to accelerate progress towards meeting the ambitious 2030 global targets.1 This approach has important policy implications in relation to expanding universal health care coverage (UHC), ensuring equity, ethics and respect for human rights, enhancing and broadening strategic information, strengthening health systems with integrated delivery of interventions, pursuing sustainable, long-term financing eventually focusing on domestic resources where possible, overcoming technical barriers such as antimicrobial resistance, and promoting research across the spectrum from product development to implementation research.1

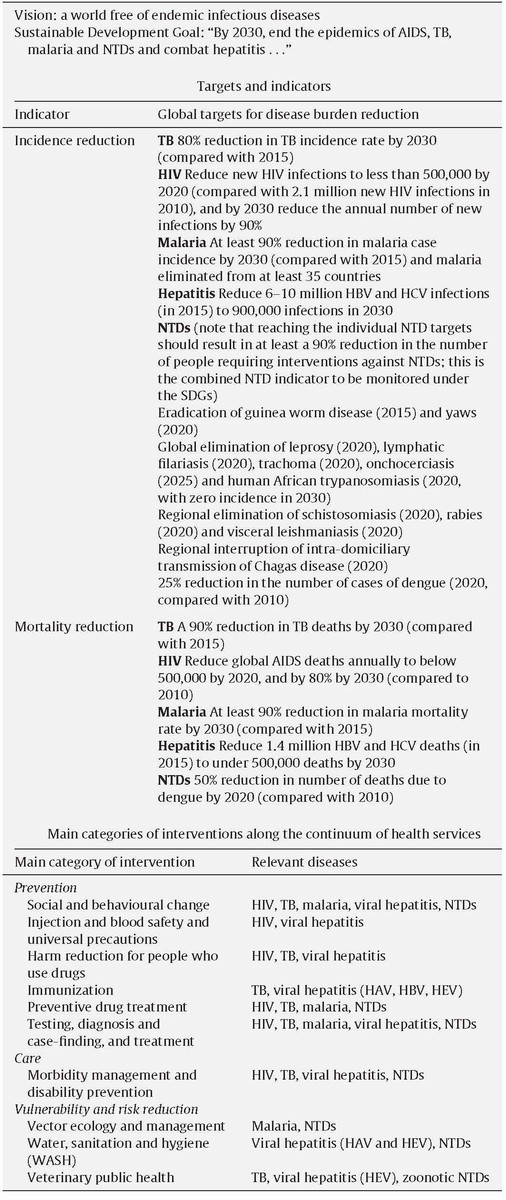

The WHO approach draws on the common elements of the individual global public health strategies to end the epidemics of TB,3 HIV,4 malaria,5 and NTDs6 and to combat hepatitis7 by 2030. The approach embraces a bold aspiration and vision of a world free of these diseases and provides opportunities for synergies and accelerated progress. A common goal, indicators (incidence and mortality reduction) with associated targets, and often similar categories of interventions along the continuum of health services have been established (Panel). These reflect a strong shared support to Universal Health Coverage (UHC) that is bound to become the top priority of the World Health Organization,8,9 with the targets serving as milestones on the path towards it by 2030. In line with increasing recognition of the interdependence of the health care and public health fields,10 a public health approach provides the framework for the delivery through the public and private sector of effective interventions for improved care and prevention on a massive scale.

The joint approach to end the long-term epidemics of infectious diseases is underpinned by a common set of principles and key elements (Table 1). The principles include maximizing the efficient and cost-effective use of resources through good governance and stewardship, with adequate monitoring and evaluation ensuring accountability; engaging with a coalition of communities and civil society as part of the extended health system; delivering on a commitment to equity, ethics and human rights to ensure “no-one is left behind”, i.e. everyone shares equally in progress; and accelerating efforts of local adaptation of global strategies. The key elements include patient-centred care (which is at the heart of synergies between clinical medicine and public health); strong political commitment to ensure UHC and social protection; strengthening the enabling environment through multisectoral approaches and implementing health policies conducive to disease control with regulatory support; and harnessing innovation and expanding research as the drivers of improved health care.

Table 1.

The main principles of a joint global public health approach towards ending the epidemics of TB, HIV, malaria and NTDs and combating hepatitis by 2030.1

Actions within the health sector

The relationship between individual health programmes and the overall health system operations is at the heart of a joint approach to this range of diseases: strengthened and performing health systems are crucial in creating a solid platform for sustainable action. This is exemplified by the End TB Strategy,3 the second pillar of which foresees a number of policy changes that go beyond the normal realm of national TB-dedicated programmes. These includes, for instance, the need of a general policy of universal coverage and social protection to prevent people affected by TB to fall below the poverty line incurring catastrophic costs given their disease, the existence of sound essential medicine standards guaranteeing quality and proper use, of the implementation in health facilities of proper infection control practices. Likewise, both the HIV and viral hepatitis strategies stress that achieving targets will require robust and flexible health systems characterized by strong health-information systems, efficient service delivery models, a sufficient and well-trained workforce, reliable access to essential medical products and technologies, adequate health financing, and strong leadership and governance.4,7 Conversely, disease control programmes have an integral and supporting role in contributing to development of health systems, since the health benefits of these interventions go beyond the containment of specific infections.11

Interactions beyond the health sector

The achievements of sectors other than health have a fundamental role in ensuring benefits for the health of all citizens. For example, among SDGs, progress in those dealing with poverty alleviation, nutrition, education, gender equality, clean water and sanitation, affordable and clean energy, reduction of inequalities, sustainable cities and communities, climate action is crucial for a positive impact on health.2 Similarly, action on the transport sector, industrial and foreign policy, and agriculture have a profound impact on health and in particular on the infectious disease burden. In keeping with a key feature of the SDGs that development sectors are integrated and indivisible, the global public health strategies to end the epidemics of TB, HIV, malaria and NTDs and to combat hepatitis by 2030 are interconnected with broader development strategies (Table 2). Above all, the elimination of poverty (SDG1) underpins progress against the wide range of communicable diseases, with other development strategies being closely interconnected with the communicable diseases shown in the table.

Table 2.

Examples of interconnection of the relevant disease strategies with broader development strategies.

Conclusion

The new SDGs framework calls for a shift from individual disease control strategies for TB, HIV, malaria, hepatitis and NTDs to a more coherent and global public health approach that also reflects the key feature of the SDGs that development sectors are integrated and indivisible. This shift is crucial in accelerating progress and meeting the ambitious global targets set for 2030. Key strategic objectives – including accelerating the expansion of universal health coverage and social protection, reaching vulnerable populations which have so far been underserved, and bolstering research capacity and monitoring and surveillance – ultimately all depend on a strengthened focus on action in countries supported by a new global policy framework.

Role of the funding source

This paper reflects the contributions of WHO staff in developing the WHO report “Accelerating progress on HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, hepatitis and neglected tropical diseases.

Authors' contributions

The two authors contributed equally to the development of this paper.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the contributions of WHO colleagues Christopher Fitzpatrick, Richard Cibulskis, Katherine Floyd, Daniel Low-Beer, John Reeder, Dirk Engels, Pedro Alonso, Gottfried Hirnschall, and Winnie Mpanju-Shumbusho, as well as that of Gary Humphreys.

Footnotes

Available online 30 August 2017

References

- 1.WHO. Accelerating progress on HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, hepatitis and neglected tropical diseases. A new agenda for 2016–2030. 2015. World Health Organization: Geneva. http://www.who.int/about/structure/organigram/htm/progress-hiv-tb-malaria-ntd/en/. [accessed 17.05.17]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. 2015. United Nations: New York. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld. [accessed 17.05.17]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. WHO end TB strategy. 2015. World Health Organization: Geneva. http://www.who.int/tb/post2015_strategy/en/. [accessed 17.05.17]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Global health sector strategy on HIV, 2016–2021. 2016. World Health Organization: Geneva. http://www.who.int/hiv/strategy2016-2021/ghss-hiv/en/. [accessed 17.05.17]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Global technical strategy for malaria 2016–2030. 2015. World Health Organization: Geneva. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/176712/1/9789241564991_eng.pdf?ua=1. [accessed 17.05.17]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Accelerating work to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases a roadmap for implementation. 2012. World Health Organization: Geneva. http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/NTD_RoadMap_2012_Fullversion.pdf. [accessed 17.05.17]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. Draft global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis, 2016–2021. 2015. World Health Organization: Geneva. http://www.who.int/hepatitis/strategy2016-2021/Draft_global_health_sector_strategy_viral_hepatitis_13nov.pdf?ua=1. [accessed 17.05.17]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO. What is universal coverage? 2015. World Health Organization: Geneva. http://www.who.int/health_financing/universal_coverage_definition/en/. [accessed 17.05.17]. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaracostas J. Tedros elected as next WHO Director-General. Lancet. 2017. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31457-5. [published online 24.05.17]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frieden T. The future of public health. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1748-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dye C, Mertens T, Hirnschall G, Mpanju-Shumbusho W, Newman RD, Raviglione MC, et al. WHO and the future of disease control programmes. Lancet. 2013;381:413-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]