Abstract

Background

Blood neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte (N/L) ratio is an indicator of the overall inflammatory status of the body, and an alteration in N/L ratio may be found in patients with familial Mediterranean fever (FMF). The aim of this study was to investigate the interrelationship between N/L ratio and FMF.

Methods

One hundred and fifteen patients and controls were enrolled in the study. The cases in the study were categorized as FMF with attack, FMF with attack‐free period, and controls. The neutrophil and lymphocyte counts were recorded, and the N/L ratio was calculated from these parameters. All patients were diagnosed according to Tel Hashomer criteria.

Results

A total of 79 FMF patients were included in the study and all subjects were receiving colchicine treatment at the time. The serum N/L ratios of active patients were significantly higher than those of attack‐free FMF patients and controls (P < 0.001). The optimum N/L ratio cut‐off point for active FMF was 2.63 with sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of 0.62 (0.41–0.80), 0.85 (0.72–0.93), 0.67 (0.44–0.85), and 0.82 (0.69–0.91), respectively. The overall accuracy of the N/L ratio in determination of FMF patients during attack was 71%.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate that N/L ratio is higher in patients with active FMF compared with FMF patients in remission and controls, and a cut‐off value of 2.63 can be used to identify patients with active FMF.

Keywords: familial Mediterranean fever, neutrophil, lymphocyte, noninvasive, serum markers

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is a recurrent, autosomal recessive autoinflammatory disease characterized with fever and serositis, which is accompanied by pain in the abdominal area, chest, and joints. The disease is common among Mediterranean communities including Turks, Armenians, Jews, and Arabs 1. Acute‐phase reactants such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C‐reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, serum amyloid A, and cytokines such as interleukin (IL) 1β, sIL‐2R, and IL‐6 are increased during FMF attacks 2, 3. Acute‐phase response can contribute to amyloidosis. The main treatment strategy for FMF is colchicine, which significantly diminishes the incidence of amyloidosis in this population 4.

Noninvasive markers such as CRP, ESR, white blood cells (WBCs), and plasma ghrelin levels are widely acknowledged as important, both for initial diagnosis and for precisely monitoring disease activity in FMF 5. Nevertheless, an optimal test has not yet been developed. Therefore, the adjunctive use of additional serum markers may add a significant advantage for predicting disease activity and achieving diagnostic precision.

Blood neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte (N/L) ratio is a simple marker of inflammation that can be easily obtained from the differential WBC count. The N/L ratio has been used to determine disease activity and diagnosis in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and acute appendicitis 6, 7, 8. The N/L ratio has also been used to predict outcomes and disease recurrence in patients with cancer, acute pancreatitis, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease 9, 10, 11, 12. Assessment of the N/L ratio can give information about two different immune pathways. The first is related to neutrophils that are responsible for lasting inflammation and the second pathway is related to lymphocytes that demonstrate regulatory function 6. Thus, the N/L ratio is an indicator of the overall inflammatory status of the body, and an alteration in N/L ratio may be found in FMF patients with active disease. This study was undertaken to assess the interrelationship between N/L ratio and FMF.

The records of cases with FMF between May 2011 and May 2013 were reviewed retrospectively at Bozok University Faculty of Medicine. All patients were diagnosed according to Tel Hashomer criteria 1. A total of 79 FMF patients were included in the study and all subjects were receiving colchicine treatment at the time. The cases in the study were categorized as three groups. Group 1 included cases diagnosed with FMF and with ongoing attacks (n = 26), group 2 involved individuals diagnosed with FMF, but were attack‐free (n = 53, with a period of at least 2 weeks since the latest attack), and group 3 (n = 36) consisted of controls. The data were collected using the electronic patient database of the patient's latest visit. ESR, CRP, WBC, neutrophil counts, lymphocyte counts, and number of platelets were recorded. Patients with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, liver diseases, acute/chronic infections, and medication noncompliance were excluded from the study. All of the patients were on colchicine treatment (1.5 mg/day); patients receiving drugs that could potentially affect the number and function of neutrophils and lymphocytes, such as steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and immunosupressive drugs, were excluded from the study.

A two‐sided independent samples t‐test, one‐way analysis of variance, and Kruskal–Wallis H tests were used for the comparison of continuous variables and chi‐square analysis was used for categorical variables. The Siegel–Castellan test was used for multiple comparisons. Values are expressed as frequencies and percentages, mean ± standard deviation or median, and 25th to 75th percentiles. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed for the sedimentation, CRP, WBC, and N/L variables, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) values with 95% CIs were calculated and compared with each other. Also, optimal cut‐off values were determined; the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) diagnosing measures were calculated with 95% CI and Kappa tests were applied for each variable. Analyses were conducted using MedCalc (version 9.2.0.1) and R 3.0.0 softwares by considering a P‐value <0.05 as statistically significant.

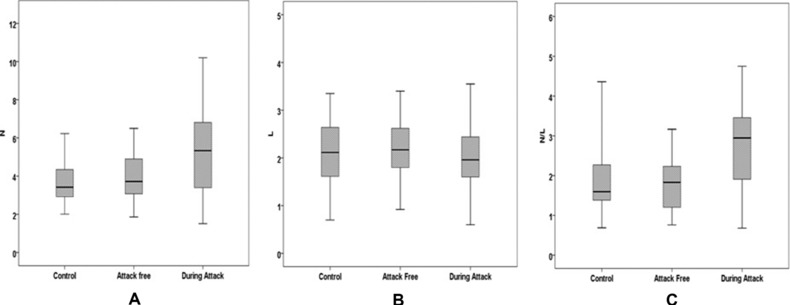

Seventy‐nine patients with FMF and thirty‐six control subjects were included in this study. There were 29 females and 50 males in the FMF group and 12 females and 24 males in the control group. The median disease duration in FMF patients was 10 years. Age and sex were similar in the FMF and control groups. The laboratory data of the patients with FMF and the controls are presented in Table 1. ESR was significantly higher in FMF patients during attack (P < 0.05). CRP increases during attack but this was not statistically significant. WBC did not differ among groups. The mean N/L ratios of the controls, FMF patients who were attack‐free, and FMF patients during attack were 1.63 (1.41–2.33), 1.83 (1.21–2.23), and 2.95 (1.91–3.46), respectively. The serum N/L ratios of FMF patients during attack were significantly higher than those of attack‐free FMF patients and controls (P < 0.05). While the serum neutrophil count increased in FMF patients during attack, in attack‐free FMF patients and controls, the serum lymphocyte count did not differ (Fig. 1). ROC curve analysis suggested that the optimum N/L ratio cut‐off point for FMF patients during attack was 2.63, with sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 0.62 (0.41–0.80), 0.85 (0.72–0.93), 0.67 (0.44–0.85), and 0.82 (0.69–0.91), respectively. The overall accuracy of the N/L ratio in determination of FMF patients during attack was 71%. There was no significant pairwise difference for AUC values between inflammatory parameters (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Comparison of Inflammatory Parameters Between Control Group and FMF Patients

| Variables | Control (n = 36) | Attack‐free FMF (n = 53) | FMF during attack (n = 26) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESR (mm/hr) | 15.50 (6.00–20.50)a,b | 11.00 (5.00–18.00)a | 24.00 (9.00–47.00)b | 0.014 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 3.34 (2.60–3.41)a | 0.80 (0.50–3.30)b | 6.70 (0.80–33.00)a | <0.001 |

| WBC (×103/mm3) | 6.75 (5.47–8.43) | 6.70 (5.90–7.97) | 7.80 (6.84–9.60) | 0.157 |

| N/L ratio | 1.63 (1.41–2.33)a | 1.83 (1.21–2.23)a | 2.95 (1.91–3.46)b | 0.004 |

Values are expressed as median (25th and 75th percentiles).

Different lowercase letters in a row indicate statistically significance difference between groups.

Figure 1.

Box plots to display the variation of N (A), L (B), and N/L (C) values between control group and FMF patients.

The gene associated with FMF was mapped to the short arm of chromosome 16 called MEFV (Mediterranean fever). The transcript of this gene encodes a protein called pyrin/marenostrin consisting of 781 amino acids, which has a crucial role in the regulation of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL‐1β 13. Pyrin dysregulation promotes an exaggerated production of IL‐ 1β. Overproduction of IL‐ 1β causes fever and hepatic acute‐phase response that can contribute to amyloidosis. Also, this mediator induces neutrophilia by stimulating bone marrow and induces expression of cell adhesion molecules, which results in neutrophil recruitment to the involved sites 3. In this study, the high levels of N/L ratio in active FMF patients, compared to attack‐free FMF patients and controls, confirm that neutrophils have a key role in the inflammatory process of FMF and disease pathophysiology.

Blood N/L ratio is an available marker of inflammation that can be easily obtained from the differential WBC count. We can obtain information about two different immune pathways from the N/L ratio. The first is related to neutrophils that are responsible for lasting inflammation and the second to lymphocytes that demonstrate the regulatory pathway 9, 10. The N/L ratio is correlated with disease severity in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease 14. It is superior to total WBC in predicting adverse outcomes in acute pancreatitis 10. Studies showed that the N/L ratio is higher in patients with active UC compared with controls and UC patients in remission 6, 15. Also, it seems to be more sensitive than WBC in the diagnosis of appendicitis and N/L ratio (>8) is significantly associated with gangrenous appendicitis 7, 8. During this study process, Ahsen et al. concluded that in FMF patients N/L ratio can be used as an acute‐phase protein, such as CRP 16. They found that the N/L ratio values of the FMF patients, during attack‐free period, were significantly higher than those of the control group. They did not include FMF patients during attack. According to our study results, the serum N/L ratios of FMF patients during attack were significantly higher than those of attack‐free FMF patients and controls, but they did not differ between attack‐free and control groups. N/L ratio could be an important measure of systemic inflammation in FMF patients during attack as it is cost‐effective, readily available, and can be calculated easily.

Colchicine is the primary treatment option in FMF patients. It prevents the occurrence of amyloidosis and decreases attack duration and frequency 4. The main effect of colchicine on the disease mechanism or pathway is unknown. In our study, all of our patients were receiving colchicine treatment and it seems that bone marrow stimulation by the cytokine pathways was not affected by colchicine treatment. It is more reasonable to suggest that colchicine may markedly affect the neutrophil functions as chemotaxis rather than neutrophilia. The results of some studies indicate that most of the anti‐inflammatory effects of colchicine are due to disruption of microtubule function, which is a critical element in neutrophil chemotaxis 1, 17.

This study has some limitations, including the cross‐sectional design and relatively small sample size, and was not designed to elucidate the mechanistic pathways that lead to higher N/L ratio in patients with FMF. In conclusion, this study showed that the N/L ratio, an indicator of the overall inflammatory status of the body, is higher in active FMF patients than in FMF patients in remission and healthy controls. A cut‐off value of 2.63 can be used to identify patients with active FMF. N/L ratio is not related with disease duration and inflammatory markers such as CRP and ESR in FMF patients. It is an inexpensive and readily available measure that could, in combination with other markers, help identify patients with active disease.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Soriano A, Manna R. Familial Mediterranean fever: new phenotypes. Autoimmun Rev 2012;12(1):31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bagci S, Toy B, Tuzun A, et al. Continuity of cytokine activation in patients with familial Mediterranean fever. Clin Rheumatol 2004;23(4):333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ozkurede VU, Franchi L. Immunology in clinic review series; focus on autoinflammatory diseases: role of inflammasomes in autoinflammatory syndromes. Clin Exp Immunol 2012;167(3):382–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Onen F. Familial Mediterranean fever. Rheumatol Int 2006;26(6):489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Polat Z, Kilciler G, Ozel AM, et al. Plasma ghrelin levels in patients with familial Mediterranean fever. Digest Dis Sci 2012;57(6):1660–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Celikbilek M, Dogan S, Ozbakir O, et al. Neutrophil‐lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of disease severity in ulcerative colitis. J Clin Lab Anal 2013;27(1):72–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yazici M, Ozkisacik S, Oztan MO, Gursoy H. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in the diagnosis of childhood appendicitis. Turk J Pediatr 2010;52(4):400–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ishizuka M, Shimizu T, Kubota K. Neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio has a close association with gangrenous appendicitis in patients undergoing appendectomy. Int Surg 2012;97(4):299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sharaiha RZ, Halazun KJ, Mirza F, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of postoperative disease recurrence in esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18(12):3362–3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Azab B, Jaglall N, Atallah JP, et al. Neutrophil‐lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of adverse outcomes of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2011;11(4):445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kalay N, Dogdu O, Koc F, et al. Hematologic parameters and angiographic progression of coronary atherosclerosis. Angiology 2012;63(3):213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duffy BK, Gurm HS, Rajagopal V, Gupta R, Ellis SG, Bhatt DL. Usefulness of an elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in predicting long‐term mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2006;97(7):993–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Federici S, Caorsi R, Gattorno M. The autoinflammatory diseases. Swiss Med Wkly 2012;142:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alkhouri N, Morris‐Stiff G, Campbell C, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio: a new marker for predicting steatohepatitis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liv Int 2012;32(2):297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Torun S, Tunc BD, Suvak B, et al. Assessment of neutrophil‐lymphocyte ratio in ulcerative colitis: a promising marker in predicting disease severity. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2012;36(5):491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahsen A, Ulu MS, Yuksel S, et al. As a new inflammatory marker for familial mediterranean fever: Neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio. Inflammation 2013;36(6):1357–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stroka KM, Hayenga HN, Aranda‐Espinoza H. Human neutrophil cytoskeletal dynamics and contractility actively contribute to trans‐endothelial migration. PloS One 2013;8(4):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]