Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study is to elucidate the association between α‐synuclein (SNCA) polymorphisms and the risk of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Methods

The PCR‐RFLP was applied to detect SNCA gene rs6532190, rs3775430, and rs10516846 polymorphisms in 98 AD patients and 105 healthy elderly.

Results

The GG frequency of rs10516846 was evidently increased in AD group than control group (P < 0.05). There was a significant difference in SNCA level between the AD and control groups (P < 0.01). In the AD group, the SNCA level in cerebrospinal fluid of GG (rs10516846) carriers was increased as compared with AA carriers (P < 0.05). The GG (rs10516846) frequency of the early‐onset AD group is significantly higher than that of the late‐onset AD group (P < 0.05). The frequency of rs3775430 GG was lower in the early‐onset group than that in the late‐onset group (0% vs. 16.7%). The SNCA level in cerebrospinal fluid of GG (rs10516846) carriers in the early‐onset AD group is higher than that of AA carriers (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

SNCA gene polymorphism may be associated with an increased risk of AD and GG genotype of rs10516846 and elevated SNCA level in CSF may increase the risk of early‐onset AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Polymorphism, Risk, rs10516846, SNCA

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD), also called primary degenerative dementia of the Alzheimer's type or senile dementia of the Alzheimer type, is a degenerative disorder of the central nervous system 1. The major clinical manifestations are progressive decline in memory, cognitive impairment, and neuropsychological disorders 2. AD patients commonly divided into early‐onset patients aged 65 years or late‐onset patients older than 66, which accounts for 94% of total AD patients 3. Genetic factors or environmental factors were reported to be involved in the formation of AD. So far, there were many genes related to AD widely reported, such as Cathepsin D Ala224Val gene, Apolipoprotein E 4, 5. It is of great clinical diagnostic significance of early AD to find more new genes or genetic mutation sites.

The SNCA gene encodes α‐synuclein, located on chromosome 4q21–23, to some extent, to presynaptic terminals that modulates vesicle trafficking as well as neurotransmitter release 6. In 1997, an association between α‐synuclein and Parkinson's disease (PD) was initially reported when a missense mutation (A53T) in SNCA caused autosomal dominant Parkinsonism 7. Subsequently, triplication of the SNCA gene was revealed to result in dominant early‐onset PD, implying that overexpression of wild‐type α‐synuclein could cause neurodegenerative disease 8, 9. Shortly thereafter, interest in the link between SNCA gene polymorphism and PD increased 10, 11. At the same time, many researchers discovered that substantial aggregation of SNCA participated in the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative diseases, such as PD, AD, multiple systems atrophy (MSA), and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) 12, 13. Thus, here we put forward a hypothesis that SNCA gene polymorphism is associated with the susceptibility to AD. In this study, we investigated the association between SNCA single‐nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), rs6532190, rs3775430, and rs10516846, and the risk of AD.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects

This study included 98 AD patients as an AD group from the outpatients and inpatients in Linyi People's Hospital between January 2014 and November 2014. The 98 AD patients were subgrouped as an early‐onset AD group (<65 years old) and a late‐onset AD group (≥65 years old). Inclusion criteria: (a) the age of patients are above 60 years old and all are Han nationality; (b) patients meet the criteria for AD diagnosis set by CCMD‐3 and DSM‐IV 14; (c) MMSE was applied to evaluate cognitive ability with scores less than 24 points 15; (d) patients whose immediate relatives do not have dementia or mental illness. Exclusion criteria: (a) vascular dementia; (b) systemic disease and dementia caused by substance intoxication; (c) pseudodementia and other senile dementia; (d) co‐existed nervous system disorders; (e) patients in the acute stage of heart, vessels, lung, liver, and kidney, etc.; (f) medical history of sudden onset, early epilepsy, dystropy, and focal neurological symptoms and early extrapyrimidal symptoms; (g) other diseases causing hypomnesis or similar symptoms. At the same time, we selected 105 healthy elderly individuals as a control group from Han nationality without a family medical history of dementia, cognitive impairment, serious physical diseases, not being in the acute stage of heart, vessels, lung, liver kidney disorders, depression, and anxiety as control group with MMSE scores more than 28 points. This study was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital and all participants or their families in this study agreed and signed the informed consents.

Sample Collection

Venous blood (10 ml) was collected from the elbow of each subject after fasting for 10–12 hr in the early morning. Venous blood (5 ml) was anticoagulated by using ethylenediaminetetraacetic aid (EDTA) and then stored at −80°C. One hour later, samples were centrifuged (3,000 rpm) at room temperature for 10 min and peripheral blood mononuclear cells were separated. We extracted genome DNA from leukocyte in peripheral blood using genomic DNA extraction kit (DP318‐03) (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) 16. Other samples were also centrifuged (3,000 rpm) at room temperature for 10 min and stored at −80°C for further use. Lumber puncture was performed to collect cerebral spinal fluid (CSF). And we vertically injected 0.5% lidocaine into the skin from the point of puncture to anesthetize. We withdrew the needle after reaching supraspinous ligament; after anaesthetization, we vertically pierced the needle into the back from the point of puncture and CSF flew out of the body after withdrawing the core needle when the resistance sharply reduced. We extracted three tubes (2–3 ml) of CSF (after extracting CSF, we inserted the core needle and withdrew the puncture needle. We used the antiseptic gauze to cover the punctured skin and slightly pressed the skin to prevent bleeding and taped the gauze and asked patients to lie down for 4–6 hr). CSF (if it was bloody, put it in a 2,500 rpm centrifuge for 3 min) was stored at −20°C for further use (http://www.biomart.cn/experiment/648/651/43761.htm).

SNP Detection

We chose SNP rs6532190, rs3775430, and rs10516846 of SNCA gene as the research target. PCR‐RFLP method was used to test allelic polymorphism and genotype frequency distribution in different sites between AD group and control group. PCR primers were designed by Premier 5.0 and primers were synthesized by Sangon, Shanghai. Amplified loci, primer sequences, fragment length, annealing temperature, times of cycles were shown in Table 1. PCR reaction system contains 2 μl of 10 × PCR reaction buffer, 2 μl of dNTP (2.5 mmol/L each), 0.5 μl of upstream primer (10 pmol/μl), and 0.5 μl of downstream primer (10pmol/μl), 2.5U Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Shanghai) and 50 ng of genome DNA. PCR reaction condition: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing for 30 s with annealing temperature of 58°C, 58°C, and 57°C, and an extension at 72°C for 40 s, total 32 cycles and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Restriction enzyme reaction system (total 20 µl) was as follows: PCR product (17 µl), BlnI (10 U/µl) (Takara Biotechnology (Dalian) Co., LTD., China)/Bse8I (10 U/µl) (MBI Fermentas, Hanover, MD)/BtrI (5 U/µl) (NEB Company, Beverly, MA) 1 µl, buffer 2 µl. After mixing well, the reaction system was subject to water bath for 6 hr, followed by the addition of 2 µl 10× loading buffer to stop reaction. Amplified products were electrophoresed on 3% agarose gel. Amplified products were sent to Invitrogen for sequencing and SNP genotype was identified according to the sequencing results.

Table 1.

Primer sequences of three SNPs (rs65324190, rs3775430, and rs10516846) of SNCA gene

| SNP | Primer | Sequence length (bp) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs65324190 | 5′‐TGAATGTCTACTTCTTTGTCTT‐3′ | 345 | 58 | 32 |

| 5′‐ GTGGTTTCCAGGAACCTTT‐3′ | ||||

| rs3775430 | 5′‐ CTTCATTTACACCTGAAG‐3′ | 232 | 58 | 32 |

| 5′‐ AAAACACATAGAAATTTTA‐3′ | ||||

| rs10516846 | 5′‐ ATTGGGAGAGAGTGTAAA‐3′ | 220 | 57 | 32 |

| 5′‐ GGTCAGTTCTCAGGCA‐3′ |

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Protein Detection

We determined the SNCA level in CSF of all subjects using the SNCA ELISA kit (YS01449B, Shanghai Yaji Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). We determined the OD value of each hole with a wavelength of 450 nm and used the concentration of standard products and OD value to calculate the linear regression equation of standard curve and finally calculated the concentration of samples. All the samples were determined twice with the average obtained.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed by using SPSS.18.0 (IBM Corporation, Somers, NY, USA). Measurement data were presented with mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD); comparisons between two groups were conducted using t‐test or variance analysis. Count data were presented with percentage and tested by chi‐square test; genotype frequency distribution of different SNP was evaluated whether they corresponded to Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium by chi‐square test. Difference on genotype frequency between two groups were analyzed using unconditional logistic regression to calculate odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Binary logistic regression analysis was employed to elucidate the association between age, SNCA level in CSF, gender, three SNPs, and the risk of AD. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Information

The AD group covered 98 patients consisting of 31 males and 67 females, who aged 61–90 years with a mean age of 74.5 ± 6.9 years. Their courses of diseases were between 1 and 10 years with mean of 5.3 ± 2.9 years. The control group included 105 subjects (39 males and 66 females) whose age ranged from 60 to 88 years, with a mean age of 73.9 ± 7.5 years. No significant difference was observed between the AD group and control group in terms of gender (χ2 = 0.681), age (t = 1.304) and systemic diseases (all P > 0.05). The AD group was subgrouped as an early‐onset AD group (<65 years old) and a late‐onset AD group (≥65 years old), and these two subgroups exhibited significant differences in age and course of disease (both P < 0.05), but not in the gender and MMSE score (both P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline information of subjects in the early‐onset AD and late‐onset AD groups

| Early‐onset AD (n = 26) | Late‐onset AD (n = 72) | t/χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 8/18 | 23/49 | 0.01 | 0.912 |

| Age | 68.4 ± 3.7 | 76.8 ± 6.4 | 6.31 | <0.01 |

| Course of disease | 6.3 ± 2.7 | 5.0 ± 2.9 | 1.99 | 0.049 |

| MMSE score | 16.6 ± 4.3 | 17.7 ± 4.1 | 1.16 | 0.25 |

AD, Alzheimer's disease; M, male; F, female.

SNCA SNPs Between the AD Group and Control Group

The genotype frequency distribution of SNCA SNP rs6532190, rs3775430, and rs10516846 in the AD group and control group corresponded to Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (all P > 0.05), which showed that genotype frequency of three SNPs were at equilibrium and representative. As shown in Table 3, the differences in genotype distribution frequency of rs10516846 between AD group and control group were statistically significant (P < 0.05): mutant genotype frequency in AD group (42.9%) was significantly higher than control group (29.5%) (P < 0.05). The differences were not statistically significant between genotype distribution frequency of rs10516846 and rs3775430 between AD group and control group (both P > 0.05). Furthermore, the differences in recessive models of rs10516846 were statistically significant between two groups (GG vs. AG + AA, P = 0.048, OR = 1.790, 95% CI = 1.003–3.197); the differences in rs10516846 allele distribution were statistically significant (G vs. A, P = 0.022, OR = 1.587, 95% CI = 1.068–2.358).

Table 3.

Comparison of genotype frequency among three SNPs (rs65324190, rs3775430, and rs10516846) of SNCA gene in the control and AD groups

| Genotype | Control group (n = 105) (%) | AD group (n = 98) (%) | P | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs65324190 (A > T) | ||||||

| AA | 54 (51.4) | 56 (57.1) | Ref | |||

| AT | 39 (37.1) | 37 (37.8) | 0.766 | 0.915 | 0.510–1.642 | |

| TT | 12 (11.4) | 5 (5.1) | 0.099 | 0.402 | 0.133–1.217 | |

| Dominant | AA | 54 (51.4) | 56 (57.1) | Ref | ||

| AT + TT | 51 (48.6) | 42 (42.9) | 0.415 | 0.795 | 0.4569–1.382 | |

| Allele | A | 147 (70.0) | 149 (76.0) | Ref | ||

| T | 63 (30.0) | 47 (24.0) | 0.173 | 0.737 | 0.474–1.144 | |

| rs3775430 (A > G) | ||||||

| AA | 57 (54.3) | 49 (50.0) | Ref | |||

| AG | 39 (37.1) | 37 (37.8) | 0.743 | 1.104 | 0.612–1.991 | |

| GG | 9 (8.6) | 12 (12.2) | 0.360 | 1.551 | 0.603–3.991 | |

| Recessive | AG + AA | 96 (91.4) | 86 (87.8) | Ref | ||

| GG | 9 (8.6) | 12 (12.2) | 0.391 | 1.488 | 0.598–3.706 | |

| Allele | A | 153 (72.9) | 135 (68.9) | Ref | ||

| G | 57 (27.1) | 61 (31.1) | 0.378 | 1.213 | 0.790–1.863 | |

| rs10516846 (A > G) | ||||||

| AA | 29 (27.6) | 18 (18.4) | Ref | |||

| AG | 45 (42.9) | 38 (38.8) | 0.408 | 1.360 | 0.656–2.823 | |

| GG | 31 (29.5) | 42 (42.9) | 0.040 | 2.183 | 1.032–4.618 | |

| Recessive | AG + AA | 74 (70.5) | 56 (57.1) | Ref | ||

| GG | 9 (8.6) | 12 (12.2) | 0.048 | 1.790 | 1.003–3.197 | |

| Allele | A | 103 (49.0) | 74 (37.8) | Ref | ||

| G | 107 (51.0) | 122 (62.2) | 0.022 | 1.587 | 1.068–2.358 | |

AD, Alzheimer's disease; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

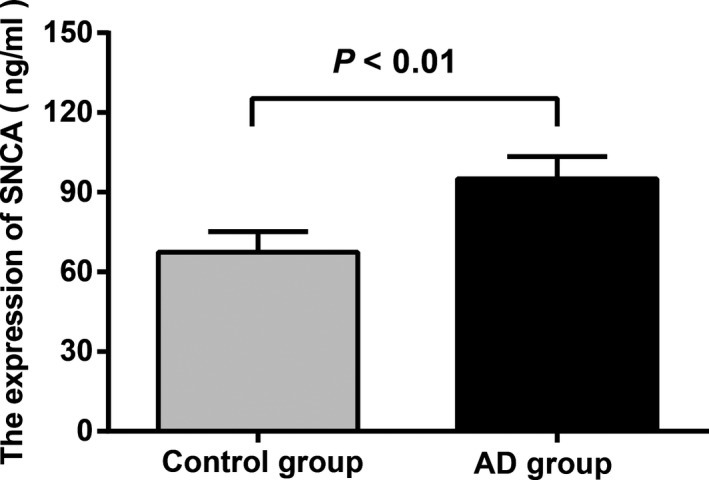

Comparison of SNCA Expression Levels

The SNCA expression levels were higher in the AD group (95.1 ± 8.3 ng/ml) than those in the control group (67.4 ± 7.8 ng/ml) (P < 0.01) (Figure 1). In the AD group, the SNCA level in CSF of rs10516846 genotype carriers was significantly higher than that of genotype AA carriers (P < 0.05), while the SNCA level in CSF of rs10516846 genotype AG carriers and AA carriers had no statistical significance (P > 0.05). In the AD group, the SNCA level in CSF of rs6532190 mutant AT and TT carriers and rs3775430 mutant AG and GG carriers had no statistical significance as compared with those of AA carriers (all P > 0.05), as shown in Table 4.

Figure 1.

Comparison of SNCA level in CSF between the AD group and control group. Note: AD, Alzheimer's disease; CSF, cerebral spinal fluid.

Table 4.

Comparison of SNCA level of cerebrospinal fluid of three SNPs (rs65324190, rs3775430, and rs10516846) of SNCA gene (ng/ml)

| Genotype | SNCA level | P | t | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs65324190 | ||||

| AA (n = 56) | 94.2 ± 8.9 | Ref | ||

| AT (n = 37) | 96.4 ± 7.7 | 0.222 | 1.230 | −1.354 to 5.754 |

| TT (n = 5) | 95.2 ± 4.8 | 0.806 | 0.247 | −7.110 to 9.110 |

| rs3775430 | ||||

| AA (n = 49) | 94.2 ± 9.1 | Ref | ||

| AG (n = 37) | 96.2 ± 8.0 | 0.291 | 1.062 | −1.745 to 5.745 |

| GG (n = 12) | 95.3 ± 5.6 | 0.691 | 0.399 | −4.415 to 6.615 |

| rs10516846 | ||||

| AA (n = 18) | 91.9 ± 8.6 | Ref | ||

| AG (n = 38) | 95.3 ± 9.0 | 0.186 | 1.339 | −1.692 to 8.492 |

| GG (n = 42) | 96.3 ± 7.3 | 0.047 | 2.027 | 0.056 to 8.744 |

t, Student's t; CI, confidence interval; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Association Between SNCA SNPs and Early‐Onset and Late‐Onset AD

As shown in Table 5, the differences were statistically significant in the recessive model (GG vs. AG + AA) and allele (G vs. A) at rs10516846 between the two subgroups (both P < 0.01). The frequency of rs3775430 GG was lower in the early‐onset group than that in the late‐onset group (0% vs. 16.7%, P = 0.027), and recessive model of rs3775430 (GG vs. AG + AA) also exhibited significant difference between the two subgroups (P = 0.026). However, there was no significant difference in the genotype frequency of rs6532190 between the two subgroups (both P > 0.05). As shown in Table 6, in the early‐onset AD group, the SNCA level in CSF of rs10516846 GG carriers was significantly higher than that of AA carriers (P < 0.05): the differences were not statistically significant between AG carriers and AA carriers (P > 0.05). In late‐onset AD group, the differences were not statistically significant among AG carriers and GG carriers and AA patients (both P > 0.05). In these two subgroups, the differences in the SNCA level in CSF between carriers of different genotype were not statistically significant (all P > 0.05). Further, there was no significant difference in the SNCA protein expressions between different genotypes of rs65324190 and rs3775430 in the early‐onset AD and late‐onset AD groups (all P > 0.05).

Table 5.

Comparison of genotype frequency of three SNPs (rs10516846, rs6532190, and rs3775430) in the late‐onset AD and early‐onset AD groups

| Genotype | Late‐onset AD (n = 72) | Early‐onset AD (n = 26) | P | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs10516846 | |||||

| AA | 22 (30.6%) | 5 (19.2%) | Ref | ||

| AG | 25 (34.7%) | 4 (15.4%) | 0.630 | 0.704 | 0.168–2.955 |

| GG | 25 (34.7%) | 17 (65.4%) | 0.0561 | 2.992 | 0.947–9.452 |

| AG + AA | 47 (65.3%) | 9 (34.6%) | Ref | ||

| GG | 25 (34.7%) | 17 (65.4%) | 0.007 | 3.551 | 1.383–9.115 |

| A | 69 (47.9%) | 14 (26.9%) | Ref | ||

| G | 75 (52.1%) | 38 (73.1%) | 0.008 | 2.497 | 1.247–5.002 |

| rs6532190 | |||||

| AA | 42 (58.3%) | 14 (53.8%) | Ref | ||

| AT | 26 (36.1%) | 11 (42.3%) | 0.615 | 1.269 | 0.501–3.214 |

| TT | 4 (5.6%) | 1 (3.9%) | 0.804 | 0.750 | 0.077–7.287 |

| AT + AA | 68 (94.4%) | 25 (96.1%) | Ref | ||

| TT | 4 (5.6%) | 1 (3.9%) | 0.734 | 0.680 | 0.072–6.383 |

| A | 110 (76.4%) | 39 (75.0%) | Ref | ||

| T | 34 (23.6%) | 13 (25.0%) | 0.841 | 1.078 | 0.516–2.252 |

| rs3775430 | |||||

| AA | 34 (47.2%) | 15 (57.7%) | Ref | ||

| AG | 26 (36.1%) | 11 (42.3%) | 0.928 | 0.959 | 0.378–2.433 |

| GG | 12 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.027 | 0.089 | 0.005–1.602 |

| AG + AA | 60 (83.3%) | 26 (100%) | Ref | ||

| GG | 12 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.026 | 0.091 | 0.005–1.601 |

| A | 94 (65.3%) | 41 (78.8%) | Ref | ||

| G | 50 (34.7%) | 11 (21.2%) | 0.070 | 0.504 | 0.239–1.067 |

AD, Alzheimer's disease; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Table 6.

Comparison of SNCA level of cerebrospinal fluid of three SNPs (rs10516846, rs6532190, and rs3775430) (ng/ml)

| SNP | AD type | Genotype | SNCA level | P | t | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs10516846 | Late‐onset AD | AA (n = 22) | 93.7 ± 8.5 | Ref | ||

| AG (n = 25) | 95.7 ± 8.7 | 0.431 | 0.795 | −3.068 to 7.068 | ||

| GG (n = 25) | 96.6 ± 7.4 | 0.218 | 1.251 | −1.770 to 7.570 | ||

| Early‐onset AD | AA (n = 5) | 85.7 ± 8.1 | Ref | |||

| AG (n = 4) | 92.0 ± 12.6 | 0.5 | 0.712 | −11.150 to 20.750 | ||

| GG (n = 17) | 95.9 ± 7.5 | 0.034 | 2.274 | 0.720–16.680 | ||

| rs6532190 | Late‐onset AD | AA (n = 42) | 95.9 ± 8.3 | Ref | ||

| AT (n = 26) | 95.0 ± 8.6 | 0.67 | 0.429 | −5.092 to 3.292 | ||

| TT (n = 4) | 96.5 ± 3.5 | 0.888 | 0.142 | −7.904 to 9.104 | ||

| Early‐onset AD | AA (n = 14) | 93.7 ± 8.8 | Ref | |||

| AT (n = 11) | 95.8 ± 8.4 | 0.552 | 0.604 | −5.092 to 9.292 | ||

| TT (n = 1) | 81.6 ± 0 | – | ||||

| rs3775430 | Late‐onset AD | AA (n = 34) | 95.3 ± 8.1 | Ref | ||

| AG (n = 26) | 95.8 ± 8.6 | 0.818 | 0.231 | −3.838 to 4.838 | ||

| GG (n = 12) | 96.1 ± 8.0 | 0.769 | 0.295 | −4.664 to 6.264 | ||

| Early‐onset AD | AA (n = 15) | 93.4 ± 10.2 | Ref | |||

| AG (n = 11) | 93.9 ± 6.6 | 0.888 | 0.142 | −6.774 to 7.774 | ||

| GG (n = 0) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | – |

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; AD, Alzheimer's disease; t, Student's t; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Logistic Regression Analysis of Risk Factors of AD

We used as the dependent variable, either AD patients or non‐AD patients, and age, SNCA expression level in CSF, gender, rs6532190 AA and non‐AA genotype, rs3775430, GG and non‐GG genotype and rs3775430 as independent variables, and conduced duality regression analysis. The result showed that rs10516846 GG genotype (P = 0.041, OR = 1.858, 95% CI = 1.027–3.364), and elevated SNCA expression level in CSF (P < 0.01, OR = 1.617, 95% CI = 1.333–1.962) were risk factors of AD (Table 7).

Table 7.

Logistic regression analysis of risk factors of Alzheimer's disease

| Dependent variable | SE | Wald | df | Sig | Exp (B) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.020 | 0.368 | 1 | 0.544 | 1.012 | 0.973–1.053 |

| Gender | 0.308 | 0.954 | 1 | 0.329 | 1.350 | 0.739–2.467 |

| (rs65324190 non‐AA) genotype | 0.292 | 1.118 | 1 | 0.290 | 0.734 | 0.414–1.302 |

| (rs3775430 GG) genotype | 0.482 | 0.934 | 1 | 0.334 | 1.593 | 0.620–4.096 |

| (rs10516846 GG) genotype | 0.303 | 4.188 | 1 | 0.041 | 1.858 | 1.027–3.364 |

| SNCA level | 0.099 | 23.785 | 1 | 0.000 | 1.617 | 1.333–1.962 |

SE, standard deviation; df, degrees of freedom; Sig: P value; Exp(B), adjusted odds; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

Previous studies on SNCA gene polymorphism paid more attention to its correlation with PD 11, 17. In this study, we explore the association of SNCA gene polymorphisms (rs6532190, rs3775430, and rs10516846) and the risk of AD. The present study results revealed that the correlation between rs10516846 and AD was evidently noted in the polymorphism screening of SNCA in AD patients. And GG genotype was evidently associated to SNCA level in CSF.

Notably, our study found that the SNCA expression levels in CSF were higher in the AD group that those in the control group. The possible reasons about abnormalities of SNCA leading to neurodegeneration are as follows: a‐synuclein localizes to the presynaptic terminal and binds to lipid membranes, which suggests that this protein is implicated in the function of synapses or synaptic turnover. Thus, the aggregation of SNCA or amyloid fibrils in the disease state results in the loss of normal functions; moreover, these effects could be amplified if other synaptic proteins interacting with a‐synuclein are also sequestered or trapped in Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, thereby disabling it from performing its synaptic functions 18. Consistent with our study, Rockenstein et al. discovered that compared to controls, levels of alpha‐synuclein were increased in cases of diffuse LBD and AD, suggesting that a critical balance among products of the synuclein gene is significant to maintain normal brain function and that changes in this balance were possibly associated with neurodegenerative disorders 19. Also, our results showed that mutation AA, mutation GG of rs10516846 was evidently different from mutation AA and significantly correlated with AD. And the difference was more evident in early AD. Compared with the expression level of AA genotype, the expression level of GG genotype was significantly increased in early or late AD in terms of expression of SNCA. And in early AD, the difference was even more significant. Thus, the mutation of rs10516846 may enhance the expression of SNCA. Zhang et al. showed that some sequences of introns can function like enhancers and cis‐regulatory elements. Grundemann et al. also supported that the mutation of the introns will influence some proteins related to transcription initiation and extension and open functional chromosome domain and then finally enhance the expression of genes 20, 21.

To the best of our knowledgeable, abnormally excessive accumulation of SNCA is one of the causes of AD because the protein concentration of SNCA had some influences on neurons. It would protect neurons at low concentrations but would contribute to neurovirulence and neuronal apoptosis at high concentration 22. Early reports of SNCA focused on its correlation with PD, and demonstrated that excessive expression of SNCA often occurs in the prefrontal area midbrain of PD patients 21, 23. While current studies exampled by Spillantini et al., confirmed that the evidently high transcription level of SNCA, especially which appeared more evidently in LBV/AD patients, is consistent with the results of our study. SNCA is one of main elements of SNCA so the formation of AD may be decided by SNCA's influence on Lewy bodies (LB) 24. Excessive expression of SNCA contributes to AD because of the interaction of SNCA and LRRK 25. According to the description of previous studies, Spillantini et al. and Fujiwara et al. found that, during the process of LBV/AD occurrence and development, the expression level of SNCA protein was abnormally enhanced with unusual phosphorylation, which were evidenced by the fact that serine 129 was phosphorylated 25, 26. The phosphorylation was caused by the effect of LPRK and was related with the excessive expression with LPRK in AD and PD 27. Therefore, in the brains of AD patients, SNCA protein was abnormally excessively accumulated, and LBV‐related symptoms and AD‐related symptoms were produced.

In summary, our study demonstrated that SNCA gene polymorphism may be associated with an increased risk of AD and GG genotype of rs10516846 and elevated SNCA level in CSF may increase the risk of early‐onset AD. Therefore, this study exhibits some medical value for the diagnostic index of early AD for reference. Further studies with larger sample size are needed to elucidate the association between SNCA gene and the occurrence and development of AD on the basis of missense mutation, and duplication or triplication of SNCA gene.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the helpful comments from our reviewers on this paper.

References

- 1. Liu S, Zeng F, Wang C, et al. The nitric oxide synthase 3 G894T polymorphism associated with Alzheimer's disease risk: a meta‐analysis. Sci Rep 2015;5:13598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Joshi YB, Giannopoulos PF, Pratico D. The 12/15‐lipoxygenase as an emerging therapeutic target for Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2015;36:181–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van der Flier WM, Pijnenburg YA, Fox NC, et al. Early‐onset versus late‐onset Alzheimer's disease: the case of the missing APOE varepsilon4 allele. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paz YMC, Garcia‐Cardenas JM, Lopez‐Cortes A, et al. Positive association of the Cathepsin D Ala224Val gene polymorphism with the risk of Alzheimer's disease in Ecuadorian population. Am J Med Sci 2015;350:219–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Al‐Asmary SM, Kadasah S, Arfin M, et al. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to schizophrenia among Saudis. Arch Med Sci 2015;11:869–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheng F, Vivacqua G, Yu S. The role of alpha‐synuclein in neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity. J Chem Neuroanat 2011;42:242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, et al. Mutation in the alpha‐synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson's disease. Science 1997;276:2045–2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, et al. alpha‐Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson's disease. Science 2003;302:841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farrer M, Kachergus J, Forno L, et al. Comparison of kindreds with parkinsonism and alpha‐synuclein genomic multiplications. Ann Neurol 2004;55:174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Fukushima W, et al. SNCA polymorphisms, smoking, and sporadic Parkinson's disease in Japanese. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18:557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guo XY, Chen YP, Song W, et al. SNCA variants rs2736990 and rs356220 as risk factors for Parkinson's disease but not for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and multiple system atrophy in a Chinese population. Neurobiol Aging 2014;35(2882):e2881–e2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shannon KM, Keshavarzian A, Mutlu E, et al. Alpha‐synuclein in colonic submucosa in early untreated Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2012;27:709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tateno F, Sakakibara R, Kawai T, et al. Alpha‐synuclein in the cerebrospinal fluid differentiates synucleinopathies (Parkinson Disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, multiple system atrophy) from Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2012;26:213–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sarazin M, deSouza LC , Lehericy S, et al. Clinical and research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2012;22:23–32,viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Neri AL, Ongaratto LL, Yassuda MS. Mini‐Mental State Examination sentence writing among community‐dwelling elderly adults in Brazil: text fluency and grammar complexity. Int Psychogeriatr 2012;24:1732–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wenham PR, Price WH, Blandell G. Apolipoprotein E genotyping by one‐stage PCR. Lancet 1991;337:1158–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Simon‐Sanchez J, van Hilten JJ, van de Warrenburg B, et al. Genome‐wide association study confirms extant PD risk loci among the Dutch. Eur J Hum Genet 2011;19:655–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Mechanisms of Parkinson's disease linked to pathological alpha‐synuclein: new targets for drug discovery. Neuron 2006;52:33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rockenstein E, Hansen LA, Mallory M, et al. Altered expression of the synuclein family mRNA in Lewy body and Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res 2001;914:48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang Y, Ma K, Song S, et al. Peroxisomal proliferator‐activated receptor‐gamma coactivator‐1 alpha (PGC‐1 alpha) enhances the thyroid hormone induction of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT‐I alpha). J Biol Chem 2004;279:53963–53971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grundemann J, Schlaudraff F, Haeckel O, et al. Elevated alpha‐synuclein mRNA levels in individual UV‐laser‐microdissected dopaminergic substantia nigra neurons in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Nucleic Acids Res 2008;36:e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cabeza‐Arvelaiz Y, Fleming SM, Richter F, et al. Analysis of striatal transcriptome in mice overexpressing human wild‐type alpha‐synuclein supports synaptic dysfunction and suggests mechanisms of neuroprotection for striatal neurons. Mol Neurodegener 2011;6:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chiba‐Falek O, Lopez GJ, Nussbaum RL. Levels of alpha‐synuclein mRNA in sporadic Parkinson disease patients. Mov Disord 2006;21:1703–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, et al. Alpha‐synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 1997;388:839–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fujiwara H, Hasegawa M, Dohmae N, et al. alpha‐Synuclein is phosphorylated in synucleinopathy lesions. Nat Cell Biol 2002;4:160–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walker DG, Lue LF, Adler CH, et al. Changes in properties of serine 129 phosphorylated alpha‐synuclein with progression of Lewy‐type histopathology in human brains. Exp Neurol 2013;240:190–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Qing H, Wong W, McGeer EG, et al. Lrrk2 phosphorylates alpha synuclein at serine 129: Parkinson disease implications. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009;387:149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]