Abstract

Background

In recent years, white blood cells (WBCs) and their subtypes have been studied in relation to inflammation. The aim of our study was to assess the relationship between neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and ankylosing spondylitis (AS).

Materials and methods

We enrolled a total of 177 patients, 96 AS and 81 healthy controls. Complete blood count, WBC, neutrophil and lymphocyte levels were measured, and the NLR was calculated. In the assessment of AS, we used the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C‐reactive protein (CRP), the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index.

Results

In the present study, 96 AS and 81 healthy individuals were enrolled. The mean age was 43.8 ± 12.9 and 46.5 ± 11.2 years, respectively. Mean disease duration of AS patients was 6.9 ± 5.6 years (median = 5, min–max = 1–25). The patients with AS had a higher NLR than the control individuals (mean NLR, 2.24 ± 1.23 and 1.73 ± 0.70, respectively, P < 0.001). A statistically significant positive correlation was observed between NLR and CRP (r = 0.322, P = 0.01). The patients receiving antitumor necrosis factor α therapy had a lower NLR than the patients receiving nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug therapy (mean NLR, 1.71 ± 0.62 and 2.41 ± 1.33, respectively, P = 0.02).

Conclusion

NLR may be seen as a useful marker for demonstrating inflammation together with acute phase reactants such as CRP and in evaluating the effectiveness of anti‐TNF‐α therapy.

Keywords: ankylosing spondylitis, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio, acute phase reactants, anti‐TNF‐alpha

INTRODUCTION

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the axial skeleton of uncertain etiology characterized by backache and morning stiffness 1. Elevation of acute phase reactants, such as C‐reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), is frequently encountered in AS. Elevated CRP and ESR values in patients with peripheral arthritis are greater than in patients with axial disease 2. Therefore, in AS acute phase reactants with the disease activity index may be used an indicator of disease activity, prognosis, and determining the response to treatment 3. However, CRP and ESR have suboptimal sensitivity in the diagnosis of AS 4. Recently, reports have shown that white blood cell (WBC) changes (lymphocyte, neutrophil, and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratios [NLRs]) are related to inflammatory diseases. The relative levels of circulating WBCs change in response to systemic inflammation. The bestcmd known of these is a relative lymphopenia accompanied by neutrophilia 5. WBC count and subtype counts are known as markers of inflammation in some rheumatic diseases 5. There are studies concerned with NLR in some rheumatological diseases, however, there is no information on other rheumatological diseases, such as AS. Recently, in studies conducted in patients with familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), the NLR was thought to be a useful marker for demonstrating subclinical inflammation and for following the development of amyloidosis 6, 7. Although some authors argue that the NLR may be a diagnostic test for inflammatory diseases, there are few studies that have investigated the relationship between NLR and CRP or ESR. A few previous studies have demonstrated that CRP levels are related to NLR. In these studies, a strong correlation was observed between NLR and CRP 8, 9.

The aim of this study was to determine the levels of NLR, which are calculated from routine complete blood counts, and to investigate the increase in subclinical inflammation seen in patients with AS. We also investigated the relationship between disease activity, clinical parameters, and different treatment groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample Selection

The study consisted of 96 patients with AS and 81 controls. All patients gave a consent form and this study was approved by the local ethical committee. Patients were asked about age, gender, duration of disease, the presence of concomitant chronic disease, and any drugs they were still using. ESH, CRP, the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) were used in the assessment of AS. WBC, neutrophil and lymphocyte levels in complete blood counts were measured, and NLR calculated. Patients with acute and chronic infections that might affect NLR, diabetes, hypertension, acute and chronic kidney failure, chronic hepatic disease, a history of allergic diseases, and any malignant disease were excluded.

Measurement‐Assessment Tools Used

BASDAI is an index used in defining disease activity and prognosis. It consists of seven questions concerning the patient's level of neck, back, lower back and hip pain, level of pain and swelling in the peripheral joints, level of disturbance at being touched on different parts of the body, and level and duration of morning stiffness. The mean of the last two questions is added to the total from the first five. Values of 4 and above are regarded as representing active disease 10.

BASFI is an index in which patients evaluate their own levels for ten daily life activities on the basis of the previous week experience on a 10‐point visual analog scale. A total score is thus obtained 11.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis of the data was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 15.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Continuous variables are shown as mean ± SD or median (min–max) and variable conformity with normal distribution was investigated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov/Shapiro–Wilk tests. The independent t‐test was used to compare normally distributed variables between groups, and the Mann–Whitney U‐test for non‐normally distributed variables. The independent t‐test was used to compare patient and control group mean NLR. Correlation between constant variables in the case group was examined using Spearman's correlation test. P‐value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

In the present study, we enrolled a total of 177 patients, with 96 AS and 81 healthy individuals. The mean age was 43.8 ± 12.9 and 46.5 ± 11.2 years, respectively, for the control and AS groups. Age and gender rates did not differ significantly between the control and AS groups (P > 0.05). Mean disease duration of AS patients was 6.9 ± 5.6 years (median = 5, min–max = 1–25). History of drug use of patients: 75% of patients (n = 72) received nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug therapy (NSAID) and 25% of patients (n = 24) received antitumor necrosis factor α (where tumor necrosis factor is TNF) therapy. A total of 39.6% of patients had a BASDAI score ≥4.

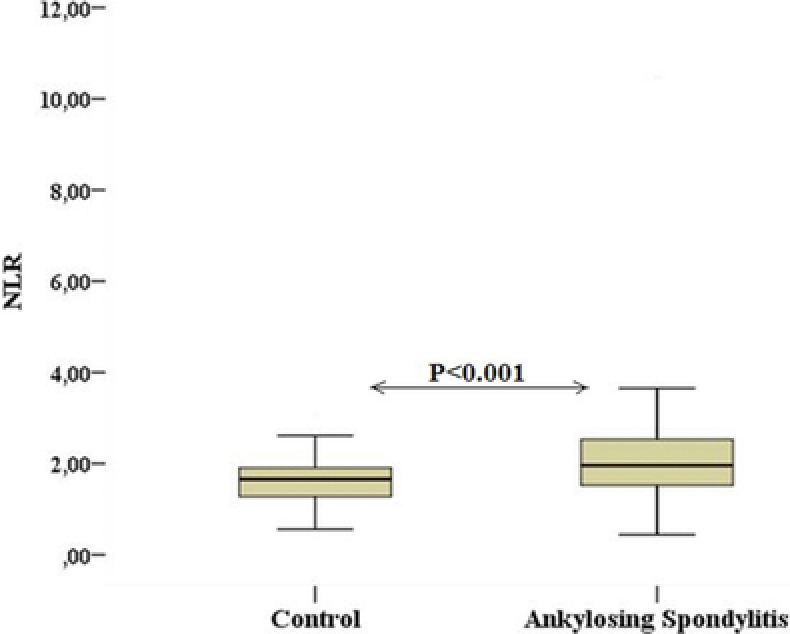

We analyzed full blood counts of the two groups. WBC count of the patient and control groups were comparable (P = 0.07). The patients with AS had higher NLR than the control individuals (mean NLR, 2.24 ± 1.23 and 1.73 ± 0.70, respectively) (Figure 1). There was a statistically significant difference for NLR between the two groups (P < 0.001). The baseline demographic and biochemical parameters of the two groups are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The comparison of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and control subjects.

Table 1.

Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics of AS Patients and Controls

| Variables | AS patients (n = 96) | Controls (n = 81) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.8 ± 12.9 | 46.5 ± 11.2 | 0.147 |

| Sex (% male) | 67.7 | 58.0 | 0.183 |

| ESH (mm/h) | 27.53 ± 17.85 | 10.48 ± 7.65 | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 1.12 ± 0.88 | 0.30 ± 0.25 | <0.001 |

| VAS (0–100 mm) | 44.27 ± 26.10 | – | – |

| BASDAI | 3.47 ± 1.94 | – | – |

| BASFI | 2.46 ± 1.95 | – | – |

| WBC (×103/μl) | 7.93 ± 2.08 | 7.30 ± 1.50 | 0.07 |

| Neutrophil (×103/μl) | 4.71 ± 1.78 | 3.84 ± 0.91 | <0.001 |

| Lymphocytes (×103/μl) | 2.31 ± 0.75 | 2.38 ± 0.60 | 0.23 |

| NLR | 2.24 ± 1.24 | 1.73 ± 0.70 | <0.001 |

ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C‐reactive protein; VAS, visual analogue scales; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; WBC, white blood cell; NLR, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio.

We performed a correlation analysis of the relationship between NLR and clinical parameters. Statistically significant positive correlations were observed between NLR and CRP (r = 0.322, P = 0.01). On the other hand, BASFI, BASDAI, disease duration, and ESR were not correlated with NLR (P > 0.05).

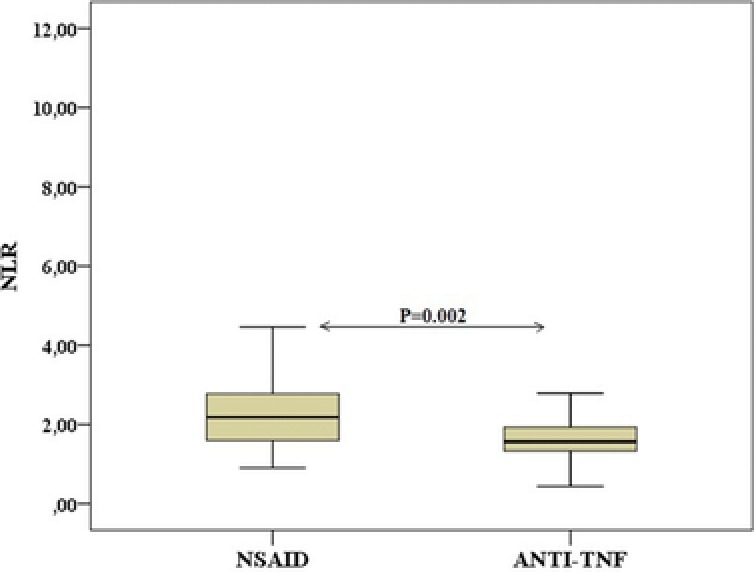

Furthermore, we evaluated the relationship between NLR and drug therapy (anti‐TNF‐α, NSAID). The patients receiving anti‐TNF‐α therapy had a lower NLR than the patients receiving NSAID therapy (mean NLR, 1.71 ± 0.62 and 2.41 ± 1.33, respectively) (Figure 2). There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.002). The baseline demographic and biochemical parameters of the two groups are presented in Table 2.

Figure 2.

The comparison of NLR in patients used NSAID and anti‐TNF‐α medications.

Table 2.

Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics According to Treatment Groups in Ankylosing Spondylitis Patients

| Variables | NSAID (n = 72) | Anti‐TNF‐α (n = 24) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.6 ± 12.9 | 47.2 ± 12.5 | 0.130 |

| ESH (mm/h) | 29.98 ± 19.28 | 20.16 ± 9.60 | 0.046 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 1.27 ± 0.92 | 0.68 ± 0.57 | 0.004 |

| VAS (0–100 mm) | 48.33 ± 27.62 | 32.08 ± 15.87 | 0.006 |

| BASDAI | 3.71 ± 2.08 | 2.77 ± 1.21 | 0.09 |

| BASFI | 2.46 ± 2.14 | 2.47 ± 1.30 | 0.706 |

| WBC (×103/μl) | 8.08 ± 2.22 | 7.48 ± 1.55 | 0.241 |

| Neutrophil (×103/μl) | 4.94 ± 1.89 | 4.03 ± 1.20 | 0.015 |

| Lymphocytes (×103/μl) | 2.25 ± 0.77 | 2.50 ± 0.63 | 0.066 |

| NLR | 2.41 ± 1.34 | 1.71 ± 0.62 | 0.002 |

ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C‐reactive protein; VAS, visual analogue scales; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; WBC, white blood cell; NLR, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found a higher NLR in patients with AS. Another important finding was that there was a strong positive correlation between NLR and CRP. Furthermore, the NLR of patients receiving anti‐TNF‐α therapy was lower than patients receiving NSAID therapy. According to our information, this is the first study of these parameters performed in patients with AS.

Numerous acute phase proteins are used in determining the degree of inflammation in rheumatic diseases, including AS. These various proteins are secreted from the liver as an effect of increased cytokine levels resulting from acute or chronic inflammatory processes. In practice, ESR and CRP tests are frequently used to assess the acute phase response 12, 13. These tests show increased values in various diseases, such as infectious diseases, malignant diseases, trauma, infarction, inflammation, arthritis, and vasculitis. In addition, these tests are used for monitoring disease activity in patients with AS 2.

There are relative changes in the circulating levels of WBCs in response to systemic inflammation. The best known of these is a relative lymphopenia accompanying neutrophilia 5. In recent years, WBC count and subtype count have been recognized as markers of inflammation in some rheumatic diseases 5. NLR is an index obtained as the proportion of neutrophils and lymphocytes, which is a hematological component of systemic inflammation. In recent studies, NLR has been used together with other inflammatory markers in determining inflammation in both rheumatic diseases and nonrheumatic diseases and it is has shown to be a good indicator of inflammation 6, 7, 14, 15. In the literature, there are a few studies showing a relationship between NLR and inflammatory rheumatic diseases 6, 7.

FMF, which is associated with defects in neutrophil function, causes an increase in chemotaxis of polymorphonuclear leukocytes during acute attacks and is characterized by amyloidosis in the chronic phase 12. Ahsen et al. studied 68 FMF patients and discovered a significantly increased NLR compared to healthy subjects. Also in this study they observed a significant positive correlation between NLR and CRP. NLR has also been found to be higher in patients with the homozygous M694V mutation of the MEFV gene located on the short arm of chromosome 16 6. The results of this study indicate that NLR may be an indicator of subclinical inflammation in FMF patients, and especially those carrying the M694V mutation need to be closely monitored 6.

Uslu et al. studied 94 FMF patients and discovered a significant increase of NLR compared to healthy subjects. Also, the NLR in patients with amyloidosis has been found to be increased. Researchers have also determined that the ratio is higher during attacks of NLR. The results of this study indicate that NLR may be a marker of rising inflammation during attacks and may be a useful marker to predict the development of amyloidosis 7.

We found that the NLR values of patients were significantly higher than those of the control group. In our study, we also observed a significant positive correlation between NLR and CRP. However, we did not observe a statistically significant difference between patients with low (BASDAI < 4) and high (BASDAI ≥ 4) disease activity scores. From the results of our study, NLR may be considered to be an indicator of inflammation, being higher in patients with AS. It is positively correlated with CRP, but has no correlation with ESR, BASDAI, or BASFI scores. NLR is not related to the AS activity index other than for CRP. We think that there are a few reasons for these results. First, ESR does not necessarily give a reflection of partially subclinical inflammation. In AS only 50% of patients with active disease have increased ESR, and measurement of the levels of ESR has been suggested to have limited value in determining disease activity 16. Therefore, NLR is not associated with ESR. CRP is a more sensitive and specific marker for inflammation compared to ESR. CRP levels continue to rapidly increase in the early phase of inflammation. A number of studies have shown that CRP is a valuable diagnostic marker of early inflammation and disease activity. Therefore, we think CRP level is more important than the relationship between CRP and NLR. However, our study did not show an association between the clinical activity index of AS (BASDAI, BASFI) and NLR. Most probably we included in this study subjects who had a lower disease activity index. Therefore, NLR is not linked to activity indices such as BASFI or BASDAI. Furthermore, new studies are needed to establish whether NLR is related to the clinical activity of AS.

The most interesting finding of our study was that the NLR of patients receiving anti‐TNF‐α therapy was lower than patients receiving NSAID therapy and that the NLR of patients receiving anti‐TNF‐α therapy compared to the control group did not show a statistically significant difference. TNF‐α is the most important factor in AS pathogenesis and anti‐TNF‐α treatment is the most effective treatment for AS patients. Several clinical and laboratory markers have been used to evaluate the effectiveness of anti‐TNF‐α treatment. We showed that CRP levels in anti‐TNF‐α treatment patients were lower than with NSAID treatment. NLR also decreased in anti‐TNF‐α treatment patients compared to NSAID patients. Furthermore, NLR was positively correlated with CRP levels. However, we did not have information on NLR values before anti‐TNF‐α treatment for the treated patients. Therefore, further research needs to be done to establish whether NLR may be a useful marker for evaluating the effectiveness of anti‐TNF‐α therapy in patients with AS.

In conclusion, our study has shown elevated NLR in AS. We also found that NLR is correlated with CRP. NLR is an important marker in the assessment of systemic inflammation that is cost‐effective and can be calculated quickly and easily. The results of this study showed that NLR was higher in patients with AS and that NLR may be seen as a useful marker in demonstrating inflammation and in evaluating the effectiveness of anti‐TNF‐α therapy.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

Reprint address: Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Medical Faculty, Kepez, Canakkale, Turkey

REFERANCES

- 1. Braun J, Sieper J. Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet 2007;369:1379–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spoorenberg A, van der Heijde D, de Klerk E, et al. Relative value of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C‐reactive protein in assessment of disease activity in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 1999;26:980–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dougados M, Gueguen A, Nakache JP, et al. Clinical relevance of C‐reactive protein in axial involvement of ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 1999;26:971–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Elyan M, Khan MA. Diagnosing ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 2006;78:12–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zahorec R. Ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte counts. Rapid and simple parameter of systemic inflammation and stress in critically ill. Bratisl Lek Listy 2001;102:5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahsen A, Ulu MS, Yuksel S, et al. As a new inflammatory marker for familial Mediterranean fever: Neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio. Inflammation 2013;36:1357–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Uslu AU, Deveci K, Korkmaz S, et al. Is neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio associated with subclinical inflammation and amyloidosis in patients with familial Mediterranean fever? BioMed Res Int 2013;2013:185317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sen N, Afsar B, Ozcan F, et al. The neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio was associated with impaired myocardial perfusion and long term adverse outcome in patients with ST‐elevated myocardial infarction undergoing primary coronary intervention. Atherosclerosis 2013;228:203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sen BB, Rifaioglu EN, Ekiz O, Inan MU, Sen T, Sen N. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a measure of systemic inflammation in psoriasis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol 2013. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2013.834498. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2286–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, et al. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: The development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2281–2285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bar‐Eli M, Ehrenfeld M, Levy M, Gallily R, Eliakim M. Leukocyte chemotaxis in recurrent polyserositis (familial Mediterranean fever). Am J Med Sci 1981;281:15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Otterness IG. The value of C‐reactive protein measurement in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1994;24:91–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tamhane UU, Aneja S, Montgomery D, Rogers EK, Eagle KA, Gurm HS. Association between admission neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2008;102:653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walsh SR, Cook EJ, Goulder F, Justin TA, Keeling NJ. Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 2005;91:181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ozgocmen S, Godekmerdan A, Ozkurt‐Zengin F. Acute‐phase response, clinical measures and disease activity in ankylosing spondylitis. Joint Bone Spine 2007;74:249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]