Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a risk factor for the development of late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD). However, the mechanism underlying the development of late-onset AD is largely unknown. Here we show that levels of the endothelial-enriched protein caveolin-1 (Cav-1) are reduced in the brains of T2DM patients compared with healthy aging, and inversely correlated with levels of β-amyloid (Aβ). Depletion of Cav-1 is recapitulated in the brains of db/db (Leprdb) diabetic mice and corresponds with recognition memory deficits as well as the upregulation of amyloid precursor protein (APP), BACE-1, a trending increase in β-amyloid Aβ42/40 ratio and hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) species. Importantly, we show that restoration of Cav-1 levels in the brains of male db/db mice using adenovirus overexpressing Cav-1 (AAV-Cav-1) rescues learning and memory deficits and reduces pathology (i.e., APP, BACE-1 and p-tau levels). Knocking down Cav-1 using shRNA in HEK cells expressing the familial AD-linked APPswe mutant variant upregulates APP, APP carboxyl terminal fragments, and Aβ levels. In turn, rescue of Cav-1 levels restores APP metabolism. Together, these results suggest that Cav-1 regulates APP metabolism, and that depletion of Cav-1 in T2DM promotes the amyloidogenic processing of APP and hyperphosphorylation of tau. This may suggest that depletion of Cav-1 in T2DM underlies, at least in part, the development of AD and imply that restoration of Cav-1 may be a therapeutic target for diabetic-associated sporadic AD.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT More than 95% of the Alzheimer's patients have the sporadic late-onset form (LOAD). The cause for late-onset Alzheimer's disease is unknown. Patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus have considerably higher incidence of cognitive decline and AD compared with the general population, suggesting a common mechanism. Here we show that the expression of caveolin-1 (Cav-1) is reduced in the brain in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. In turn, reduced Cav-1 levels induce AD-associated neuropathology and learning and memory deficits. Restoration of Cav-1 levels rescues these deficits. This study unravels signals underlying LOAD and suggests that restoration of Cav-1 may be an effective therapeutic target.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, amyloid, caveolin-1, cognition, tau, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by progressive loss of memory and cognitive decline. Pathological hallmarks in the brain include amyloid deposits, aggregates of β-amyloid (Aβ), a cleavage product of amyloid precursor protein (APP), and neurofibrillary tangles, insoluble aggregates of hyperphosphorylated tau (Jack et al., 2018). Mechanisms causing late-onset AD (LOAD) are largely unknown. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) nearly doubles the risk for AD (Ohara et al., 2011). The combined overall relative risk for dementia, including clinical diagnoses of both AD and vascular dementia, is 73% higher in people with T2DM than in those without (Gudala et al., 2013; Biessels et al., 2014). Likewise, AD patients experience brain insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia (Biessels and Reagan, 2015; Stanley et al., 2016). This suggests that insulin resistance promotes cognitive impairments leading to AD, and that insulin-deprived brains are susceptible to the development of AD. Increasing evidence suggests that endothelial and vascular factors may play a role in the development of AD (Sweeney et al., 2019). However, mechanisms by which endothelial and vascular dysfunction lead to AD are not fully elucidated.

Caveolin-1 (Cav-1) is a 22 kDa coat protein of caveolae, a subset of lipid rafts. Cav-1 can directly interact with many proteins within the lipid rafts via its scaffolding domain (Okamoto et al., 1998). Interestingly, the processing of APP in the nonamyloidogenic pathway by α-secretase, as well as in the amyloidogenic pathway by BACE1 and PS1/γ-secretase, occurs in lipid rafts (Ikezu et al., 1998; Vetrivel et al., 2004). Cav-1 plays a major role in cell signaling and molecular trafficking, such as transcytosis and endocytosis (Fridolfsson et al., 2014). In addition, Cav-1 also exists on vesicles, caveosomes, and liposomes (Razani and Lisanti, 2001a). Furthermore, Cav-1 is enriched in endothelial cells and plays a major role in regulation of trafficking via the blood–brain barrier. Cav-1 KO mice exhibit accelerated aging, including loss of synaptic density (Head et al., 2010). However, whether loss of Cav-1 in aging and pathological conditions can induce AD is not known.

Insulin resistance due to dysfunction of insulin signaling is the hallmark feature of T2DM. The insulin receptor and downstream signaling components are localized in caveolae, where they transduce insulin signaling and transcytosis via caveolae. Insulin induces the phosphorylation of Cav-1, the principal component of caveolae, in adipocytes (Mastick et al., 1995; Mastick and Saltiel, 1997). In turn, Cav-1 is critical for the formation of caveolae and for the transfer of insulin from the circulation into neural tissue through the blood–brain barrier (Fridolfsson et al., 2014). Previous studies suggest that insulin entry into muscle interstitium requires Cav-1 phosphorylation and Src-kinase activity, and that this process is impaired by insulin resistance (Wang et al., 2011). However, there is presently no evidence that caveolae and Cav-1, in particular, play a role in the etiology of insulin resistance and T2DM in human patients, let alone in the development of cognitive deficits and AD.

Here we show that Cav-1 levels are significantly reduced in the brains of T2DM patients and db/db mice, concomitantly with a significant increase in Aβ. We further show that, in the db/db mice, decreased levels of Cav-1 correlate with increased levels of full-length APP (FL-APP), BACE-1, hyperphosphorylated tau species, and impairments in the Novel Object Recognition task. Restoration of Cav-1 levels in the brains of db/db mice rescues learning and memory and reduces levels of FL-APP, BACE-1, and p-tau. To further examine whether APP metabolism and Aβ production are directly regulated by Cav-1, we used HEK cells expressing either human WT APP or familial AD (FAD)-linked APPswe and examined the effect of Cav-1 downregulation or upregulation on APP and Aβ production. We show that downregulating Cav-1 significantly upregulated FL-APP and Aβ, while upregulating Cav-1 reduced FL-APP and Aβ. Finally, we show that deletion of Cav-1 alters the distribution of APP in the plasma membrane, which may lead to its altered processing. Together, our data provide evidence that depletion of Cav-1 in the brains of T2DM induces amyloidogenic processing of APP, which results in increased levels of FL-APP and Aβ and tau hyperphosphorylation, followed by cognitive deficits and AD. This study suggests a potential mechanism underlying the development of LOAD, and implies that restoration of Cav-1 levels rescue these deficits.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Chemicals and reagents

Commercially available reagents are indicated below. Antibodies used for Western blot analysis are as follows: 6E10 (BioLegend, catalog #803001), APP-CTF (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog #A8717), AT8 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog #MN1020), Cav-1 (BD Biosciences, catalog #610060; or Cell Signaling Technology, catalog #3238S). CP13 and DA9 were graciously provided by Dr. Peter Davies (Albert Einstein Institute). Host-matched secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories. Brain endothelial cells (bEnd.3) were purchased from ATCC. Viruses were obtained from Dr. Brian P. Head's laboratory at the University of California at San Diego. Viruses used were an Ad-CMV-GFP (control) and Ad-CMV-Cav1 to overexpress Cav-1, as well as a LV-shRNA-scrambled control and AAV9-shRNA-Cav-1.

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (ACC Protocol #17–123, O.L.; and #16–204, R.D.M.). All mice used in this study were male and were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory: FVB/NJ (stock #001800), C57B6 (stock #000664), db/db (BKS.Cg-Dock7m +/+ Leprdb/J, stock #000642), and Cav-1 KO (stock #004585).

Human samples

Frozen samples of the temporal lobe of human brains of T2DM and age-matched healthy controls were obtained from the Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, University of Washington, Seattle.

Methods

Novel Object Recognition

On days 1 and 2, mice were placed in the arena for 10 min of habituation. On day 3 (familiarization phase), mice were placed in the arena with two identical objects and were allowed 20 min to explore the objects for 30 s (once the animal explored for 30 s, they were removed from the arena). On day 4 (novel object test phase), animals were reintroduced to the arena containing a familiar and novel object. Mice were allowed to explore the objects as described above. Identical and novel objects were similar in size but differed in color and shape. The location of the novel object was placed on the nonpreferred side (as determined during familiarization phase) to avoid side preference. Object exploration was recorded manually, and the percentage of exploration time of each object was computed. Discrimination ratios were calculated as previously described (Antunes and Biala, 2012). Briefly, the Discrimination Index (ratio) was calculated by dividing the difference between the time spent exploring the novel object (TN) and time spent exploring the familiar object (TF) by the total time of exploration (TN + TF). Exploration time of the familiar versus novel object during the test phase was compared and analyzed by paired t test (p < 0.05). Discrimination ratio was analyzed with the unpaired t test (p < 0.05).

Stereotaxic injection

The hippocampus targeted injections were performed using the Angle Two Small Animal Stereotaxic Instrument from Leica Biosystems. Injections were performed with a 25 gauge 1.0 ml Hamilton syringe; 0.5 μl of Ad-CMV-GFP or Ad-CMV-Cav1 was injected at the rate of the 0.1 μl/min. Coordinates are as follows: ML ±2.50 mm, AP −2.80 mm, DV −2.00 mm; and ML ±2.05 mm, AP −2.92 mm, DV −2.50 mm. Novel Object Recognition was performed 3 weeks after injection. Following behavior analysis, coronal sections were stained to confirm viral injection.

ELISA

Mouse ELISA assays were performed with brain tissue lysate as detailed in the manufacturer's protocols: mouse Aβ-40 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog #KMB3481), mouse Aβ-42 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog #KMB3441), human Aβ-40 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog #KHB3481), and human Aβ-42 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog #KHB3441).

Sucrose density fractionation

Cells and tissue were lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer (150 mm Na2CO3, pH 11) containing protease inhibitor mixture (1:100, Sigma-Aldrich) followed by sonication 3 times at 40% amplitude for 15 s on ice with 60 s incubation on ice in between cycles. Equal protein concentrations of homogenate were added to 1 ml of 80% sucrose followed by careful layering of 6 ml of 35% sucrose and 4 ml of 5% sucrose, sequentially. The samples were centrifuged at 175,000 × g with a SW41Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter) for 3 h at 4°C. Samples were collected in 1 ml aliquots with the membrane lipid rafts (MLRs) found at the 5/35% interface (fractions 4–6) and analyzed via Western blot as described above.

Statistical analysis.

MLR blots were analyzed by calculating the percentage of each target protein in each buoyant (fractions 4–6) and heavy fractions (10–12).

|

Percentages were then analyzed by unpaired Student's t test (p < 0.05).

HEK cell culture

HEK cells with the human APPswe mutation were cultured in DMEM containing GlutaMAX (Invitrogen, catalog #10569–010), 10% FBS, 1% P/S, and Geneticin (20 μl per 10 ml added before plating; Invitrogen, catalog #10131–035). Media was replaced every 48–72 h.

Splitting.

Cells were rinsed twice with sterile PBS to remove all traces of FBS. Cells were incubated in 0.25% trypsin-EDTA for 2 min at 37°C. Trypsin was neutralized with 2 volumes of warm media. Cells were collected and spun at 1000 rpm for 5 min. Cells were resuspended in media and plated at a ratio of 1:5.

Viral infection.

Cells were split as described above; however, cells were counted and resuspended in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen, catalog #31985062) containing virus (2 × 109 viral particles per 10 ml media), 1% FBS, and 1% P/S for 24 h at 37°C. Viral media was then replaced with growth media for another 48 h.

Aβ collection.

Cells were cultured as described above. Cells cultured in a 10 cm dish were incubated with 1 ml media for 2 h at 37°C. Media was collected and prepared for Western blot by adding tricine sample buffer (Bio-Rad, catalog #1610739), containing β-mercaptoethanol, at a ratio of 1:2. Samples were boiled for 10 min at 95°C and stored at −20°C.

Western blotting

Cells or tissue were collected and homogenized in lysis buffer (150 mm Na2CO3, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8) containing protease inhibitor mixture (1:100, Sigma-Aldrich, catalog #P8340) and sonicated 3 times for 15 s at 40% amplitude. Tissue was then spun at 10,000 rpm for 5 min (this step was not performed for cell lysate). Supernatants were collected, and protein quantified via microplate BCA method and normalized to equal concentrations with lysis buffer and 4× sample buffer (0.35 m Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 30% glycerol, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% SDS, bromophenol blue). Excess protein lysate (with no sample buffer) was stored at −80°C. Samples were then boiled for 10 min at 95°C; 10–15 μg of each sample was loaded into a 10% Tris-glycine gel and run in 1× Tris/glycine/SDS buffer at 115 V for 1 h and 25 min followed by transfer in 1× Tris/glycine buffer to a 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) at 125 mV for 1 h. Membranes were blocked for 30 min in 5% nonfat dry milk in PBST (PBS + 0.1% Tween 20), then incubated in primary antibody overnight at 4°C with shaking. Membranes were washed 3 times for 5 min in PBST and placed in appropriate secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature with shaking. Membranes were washed 3 times for 15 min in PBST and images with an ECL chemiluminescence substrate (GE Healthcare). Levels of protein were quantified using densiometric measurements from ImageJ Software. All protein levels were normalized to levels of actin unless otherwise noted.

Aβ detection.

Samples were prepared in tricine sample buffer (1:2) and separated on a 16.5% Tris-tricine gel (Bio-Rad, catalog #4563064). Running voltage was set at 75 V for 30 min followed 100 V for 2 h or until samples were adequately separated. Western blot transfer was done as described above. Membranes were then incubated in boiling PBS and microwaved for 5 min, followed by incubation with room temperature PBS for 5 min. Membranes were incubated in blocking buffer (5% nonfat dry milk in PBST) for 30 min. Membranes were then incubated with anti-mouse 6E10 antibody (BioLegend) overnight at 4°C with shaking. Secondary antibodies, developing, and densitometry analysis were done as described above. Levels of Aβ were compared between conditions as the same number of cells were plated before Aβ collection.

Experimental design and statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in Prism (version 7.0a; GraphPad Software). Data are mean ± SEM, and a probability of <0.05 was considered significant. For the Novel Object Recognition, a paired two-tailed t test was used. The associated discrimination ratio was analyzed with the unpaired two-tailed t test. All Western blot analyses were done by densitometry and compared using the unpaired two-tailed t test or one-way ANOVA when appropriate. Individual statistical analyses as appropriate are described in the figure legends.

Results

Cav-1 is depleted in the brains of T2DM patients and in the brains of diabetic mice

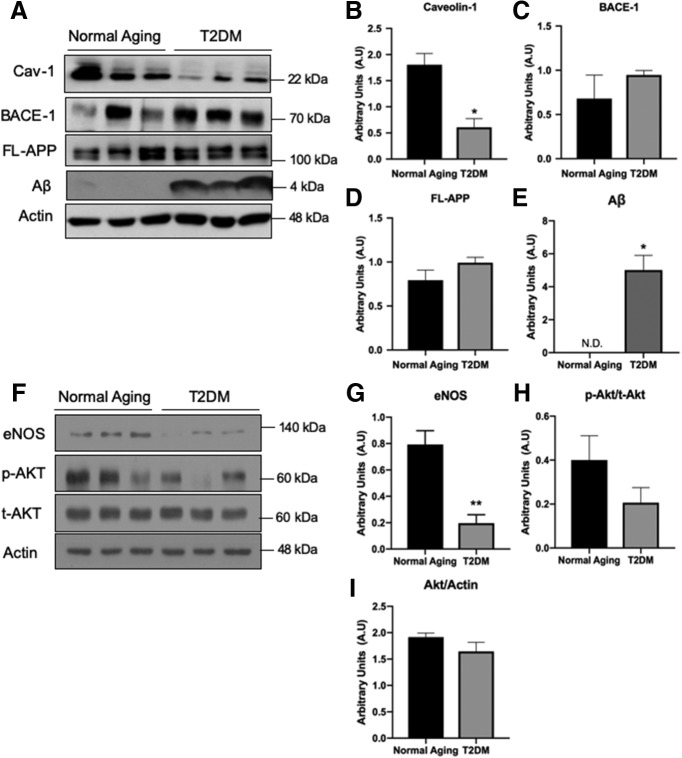

To address whether Cav-1 plays a role in the development of T2DM-induced AD, we first examined Cav-1 levels in the brains of T2DM patients. For this purpose, we compared Cav-1 protein expression in the brains of T2DM patients and age-matched healthy aging. We observed that levels of Cav-1 are significantly reduced in the brains of T2DM patients compared with normal aging (Fig. 1A,B). Lower Cav-1 coincided with an increasing trend in the levels of FL-APP and BACE-1 in the T2DM brains, albeit not statistically significant (Fig. 1A,C,D). T2DM brains had relatively high Aβ expression, in contrast to the normal aging group where it was nondetectable (Fig. 1A,E). Because Cav-1 regulates the distribution and function of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) as well as Akt signaling in endothelial cells (Wang et al., 2009), we examined whether eNOS and Akt expression levels were also affected in T2DM brains. Our results showed a significant decrease in levels of eNOS (Fig. 1F,G), yet no significant change in Akt was detected (Fig. 1F,H,I).

Figure 1.

Loss of Cav-1 in T2DM coincides with alterations in the amyloidogenic pathway and eNOS metabolism. Protein lysate from human brain hippocampal tissue of T2DM and normal aging was analyzed by Western blot. Levels of Cav-1 (A,B) are significantly decreased in the T2DM samples. Levels of BACE-1 (A,C) and FL-APP (A,D) show a trending increase in the T2DM samples, albeit not statistically significant. Levels of Aβ (A,E) are significantly increased in the T2DM cases, and are nondetectable (N.D.) in the normal aging condition. Analysis of downstream signaling of Cav-1 shows a significant decrease in eNOS (F,G), whereas no significant changes in levels of p-Akt, t-Akt, or their ratios were found (F,H,I). N = 3. *p < 0.05 (unpaired t test). **p < 0.01 (unpaired t test).

Depletion of Cav-1 in brains of diabetic mice promotes neuropathology and impairments in learning and memory

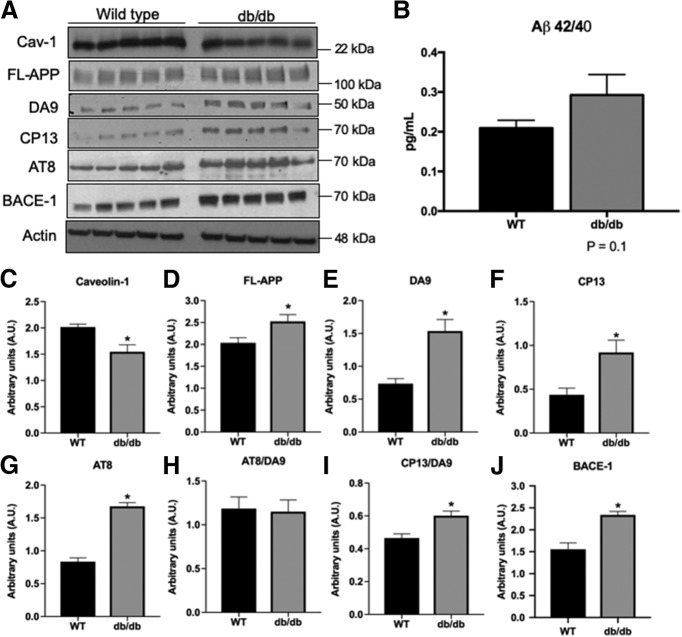

To validate that the depletion of Cav-1 in the brains of diabetic patients is replicated in an obesity-dependent T2DM mouse model, we examined the expression of Cav-1 in the hippocampus of db/db mice. Levels of Cav-1 were reduced in the brains of 12 weeks of age db/db mice (Fig. 2A,C). Given that Cav-1 plays a critical role in the maintenance, function, and structure of lipid rafts (Lajoie and Nabi, 2010), coupled with the trending increase in APP levels observed in the human samples, we asked whether depletion of Cav-1 affects APP expression. We show that reduced levels of Cav-1 coincided with increased levels of FL-APP (Fig. 2A,D) and a trending increased ratio of Aβ42/40 (Fig. 2B), suggesting that Cav-1 levels modulate the processing of APP. It should be noted that measurements of Aβ levels were performed in relatively young mice at the age of 12 weeks. It is reasonable to assume that Aβ levels will increase as a function of age and disease progression. In addition, we show that levels of BACE-1, the initiator protease of APP's amyloidogenic processing, are increased in the brains of db/db mice (Fig. 2A,J). Together with the observed decrease in Cav-1 in db/db, these results indicate the induction of AD neuropathology in this mouse model of diabetes.

Figure 2.

AD-linked neuropathological alterations in diabetic mice. A–J, A comparison of protein expression in hippocampal lysate from WT control (C57BL/6) and db/db mice shows a significant decrease in Cav-1 expression (A,C). Diabetic mice also show a significant increase in FL-APP (A,D), as well as in the levels of - DA9 (total tau) (A,E), CP13 (p-tau) (A,F), and AT8 (A,G). There was no difference in the ratio of AT8/DA9 (H); however, there was an increase in the ratio of CP13/DA9 (I). db/db mice show a significant increase in BACE-1 expression (A,J). N = 5/group. *p < 0.05 (unpaired t test). B, Quantification of the concentration of mouse Aβ42 and Aβ40 in diabetic mice was performed by ELISA. The db/db mice show a trending increase in this ratio indicating an increase in Aβ production in the hippocampus (N = 4). p = 0.1 (unpaired t test).

Next, we asked whether depletion of Cav-1 induces alterations in tau metabolism. To address this, we examined the expression of total tau and its phosphorylated forms in the brains of db/db mice. We show a significant increase in total-Tau (DA9; Fig. 2A,E) and pTau (CP13 and AT8; Fig. 2A,F,G). We did not find an increase in the AT8/DA9 ratio (Fig. 2H), suggesting that this increase may be the result of increased total levels of tau. However, a significant increase in the ratio CP13/DA9 suggests an increase in the phosphorylation of Ser202 (Fig. 2I). Both CP13 and AT8 recognize Ser202, whereas AT8 also recognizes phosphorylation of Thr205; these results may suggest reduced pThr205 in the db/db and disproportional tau phosphorylation compared with the increase in total tau.

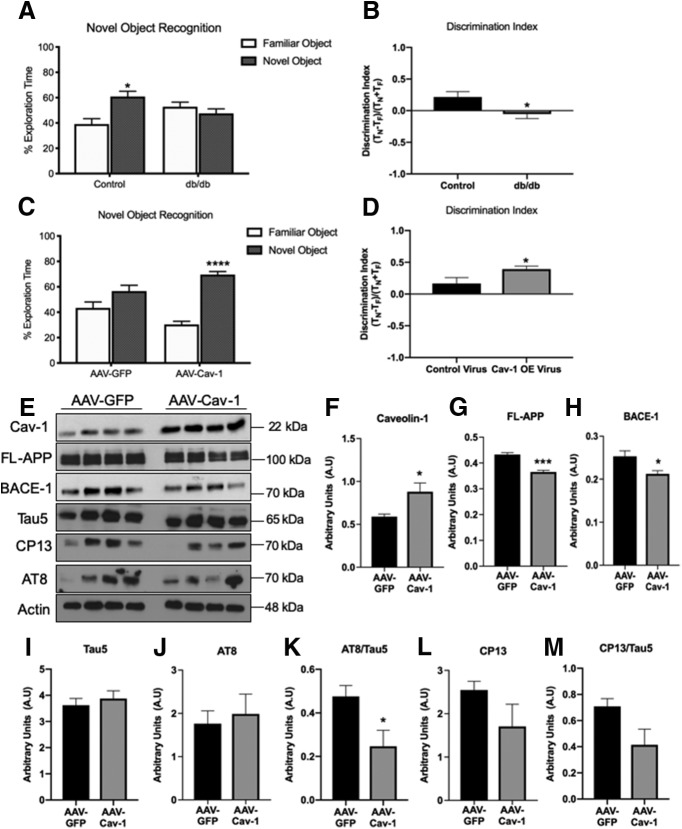

In light of the increased neuropathology in the brains of T2DM mice, we asked whether hippocampal function is compromised. To address that, we used the hippocampus-dependent object recognition test. The Novel Object Recognition task is the rodent equivalent of the visual paired comparison task, commonly used for the diagnosis of amnesia, the primary cognitive deficit underlying AD dementia (Antunes and Biala, 2012). db/db mice exhibited significant deficits in the Novel Object Recognition test at 12 weeks of age (Fig. 3A,B). To start to address whether reduced levels of Cav-1 underlie learning and memory deficits, we set out to determine whether impairments in learning and memory can be rescued by the restoration of Cav-1 levels. For this, db/db mice were injected intracranially with adenovirus vectors Ad-CMV-GFP (control) or Ad-CMV-Cav1 and their performance in the Novel Object Recognition test was examined (Fig. 3C). Ad-CMV-Cav-1-injected mice performed significantly better than Ad-CMV-GFP-injected mice (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that depletion of Cav-1 underlies impaired learning and memory of the diabetic mice, at least in part. To determine whether depletion of Cav-1 underlies enhanced amyloidogenic processing of APP and tau phosphorylation, we further examined the effect of Cav-1 rescue on the previously observed neuropathology in the brains of db/db mice. Our results show a significant decrease in expression levels of both FL-APP and BACE-1 in the hippocampi of db/db following rescue of Cav-1 levels (Fig. 3E–H). Examination of tau species showed no significant change in total levels of tau (Fig. 3E,I) or AT8 (Fig. 3E,J). Interestingly, there was a significant decrease in the ratio of AT8/tau5 (Fig. 3K), which may suggest that the relative amount of tau phosphorylated on Ser202 and Thr205 is reduced following Cav-1 restoration in the hippocampi of db/db. In addition, there was a trending decrease, albeit not statistically significant in levels of CP13 (raised against pSer202; Fig. 3E,L) and the ratio of CP13/tau5 (Fig. 3E,M). Collectively, these results suggest that pathology and hippocampal dysfunction in the brains of these diabetic mice are alleviated by increasing the expression of Cav-1.

Figure 3.

Compromised hippocampal function in db/db mice is rescued by restoring Cav-1 expression. A, B, db/db mice fail the Novel Object Recognition test at 10–12 weeks of age, whereas control mice perform it successfully (N = 13, paired t test; Discrimination Index, *p < 0.05, unpaired t test). C, D, Nine-week-old db/db mice received hippocampal injections of a control virus (AAV-GFP, Ad-CMV-GFP) or one that increased expression of Cav-1 (AAV-Cav-1, Ad-CMV-Cav1). Three weeks after injection, db/db mice were tested in the Novel Object Recognition test (N = 14/group). Those that received the Cav-1 virus displayed enhanced performance in the Novel Object Recognition test (****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, paired t test; Discrimination Index, *p < 0.05, unpaired t test). E–J, Comparison of protein expression in hippocampal lysate from db/db animals injected with either AAV-GFP (control) or AAV-Cav-1 show significant increases in Cav-1 expression (E,F), as well as decreases in both FL-APP (E,G) and BACE-1 (E,H). There are no observed changes in levels of total Tau (Tau 5; E,I) or pTau (AT8; E,J); however, there is a decrease in the ratio of AT8/Tau5 (E,K). While there is a trending decrease, there are no significant changes in levels of CP13 or the ratio of CP13/Tau5 (E,L,M). *p < 0.05 (unpaired t test).

Cav-1 modulates the amyloidogenic pathway

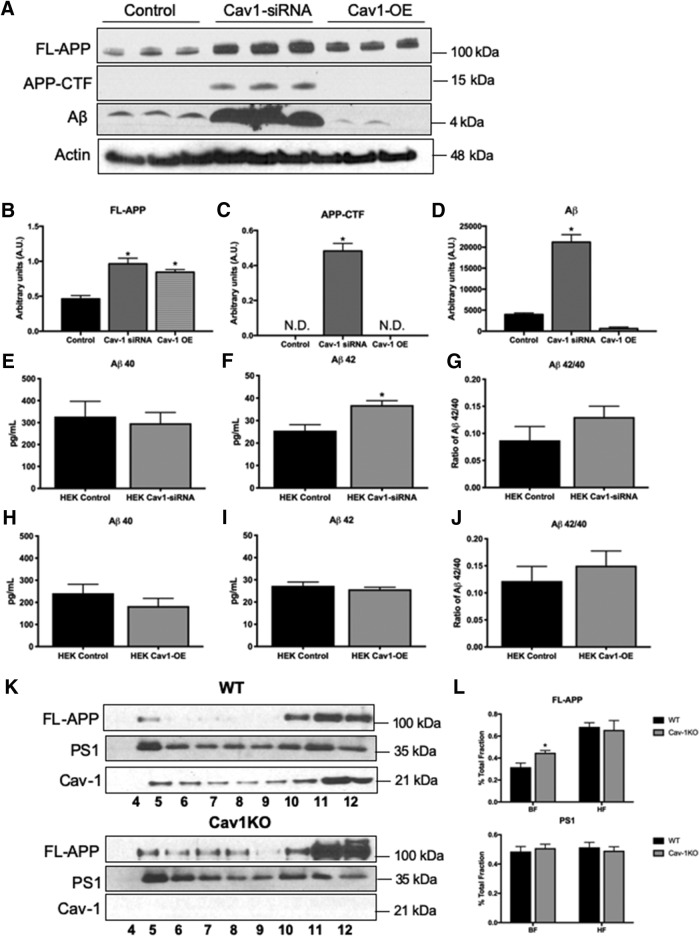

To determine whether restoration of Cav-1 levels rescue the increase in Aβ production, we used HEK cells stably expressing FAD-linked APPswe mutant form. To downregulate Cav-1, HEK-APPswe were infected with lentivirus expressing a Cav-1 shRNA (LV-shRNA-Cav-1). Control lentivirus expressed scrambled shRNA (LV-shRNA-scrambled). To upregulate Cav-1, HEK-APPswe were infected with adenovirus-expressing Cav-1 (Ad-CMV-Cav1). Control adenovirus expressed GFP (Ad-CMV-GFP). We observed that levels of Fl-APP (Fig. 4A,B), APP carboxyl terminal fragments (APP-CTFs) (Fig. 4A,C), and secreted Aβ (Fig. 4A,D) are significantly increased following downregulation of Cav-1. Overexpression of Cav-1 in HEK cells rescued this phenotype and downregulated Aβ below control levels (Fig. 4A–H). To examine the effect of Cav-1 on Aβ species, we analyzed levels of human Aβ42/40 in the infected HEK-APPswe cells using ELISA. We observed that following Cav-1 downregulation levels of Aβ40 were not changed (Fig. 4E). Levels of Aβ42 are significantly increased (Fig. 4F). The Aβ42/40 ratio is trending increase, albeit not statistically significant (Fig. 4G; p = 0.09). Upregulation of Cav-1 expression in HEK-APPswe cells does not change levels of Aβ40 (Fig. 4H). Importantly, levels of Aβ42 were downregulated and appeared comparable with control levels (Fig. 4I), and the Aβ42/40 ratio was no longer near significance (Fig. 4J). These results indicate unequivocally that Cav-1 regulates APP processing and that loss of Cav-1 facilitates the amyloidogenic pathway.

Figure 4.

Depletion of Cav-1 induces alterations in APP processing. A–D, Comparison of protein levels in HEK-APPswe cells expressing the control, Cav-1-siRNA, or Cav-1 overexpressing virus (Cav1-OE). Downregulation of Cav-1 induces increases in FL-APP (A,B), APP-CTF (A,C), and Aβ (A,D), whereas overexpression of Cav-1 partially restores FL-APP levels (A,B), and fully restores the expression levels of APP-CTF (A,C) and Aβ (A,D) (N = 3, one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons; B, F(2,6) = 19.81, p = 0.0023; C, F(2,6) = 122.7, p < 0.0001; D, F(2,6) = 107.5, p < 0.0001). E–J, Analysis of the concentration of human Aβ42 and Aβ40 secreted from HEK-APPswe cells infected with control virus, Cav-1-siRNA, or Cav-1 overexpressing virus (Cav1-OE) was performed by ELISA (N = 3). *p < 0.05 (unpaired t test). Levels of Aβ40 were unchanged (E,H), but levels of Aβ42 were significantly increased following Cav-1 downregulation (F). The ratio of Aβ42/40 shows a trending increase following Cav-1 downregulation (G; p = 0.09). Following Cav-1 upregulation, levels of Aβ42 (I) and the ratio of Aβ42/40 (J) were comparable with control. K, Western blot analysis of sucrose density fractionation probed for expression levels of FL-APP, PS1, and Cav-1. L, Quantification of sucrose density fractionation shows that Cav-1KO displays a significant increase in the expression and localization of FL-APP to the lipid raft fractions. Levels of PS1 in the lipid raft fractions are unchanged (N = 3). *p < 0.05 (unpaired t test).

One possibility is that Cav-1 regulates the localization of APP in lipid rafts, and that the depletion of Cav-1 levels induces mislocalization of APP. To start to address this, we examined APP distribution in varying membrane densities using MLR preparations and calculated the relative abundances of APP in both the buoyant (MLR) and heavy fractions. We observed significant increases in MLR localization of APP in lipid rafts prepared from the brains of Cav-1 knockout mice (Cav-1 KO) (Fig. 4K,L). The observed shift in APP localization may cause a change in its levels and/or processing pathway. In contrast, there was no change in PS1 localization, suggesting that the effect of Cav-1 is APP-specific (Fig. 4K,L).

Discussion

This study presents several novel observations. First, we show that depletion of Cav-1 in T2DM plays an important role in the development of pathology that characterizes AD. We show that Cav-1 is reduced in T2DM in human patients as well as in a well-established mouse model of the disease. Reduced Cav-1 levels coincide with increased levels of APP, BACE1, Aβ, hyperphosphorylated tau species, and impaired recognition memory.

Second, our observations that restoration of Cav-1 levels in db/db rescues recognition memory function and ameliorates pathology suggest a causal relationship between Cav-1 depletion and hippocampal function. In support of that are our observation that reducing Cav-1 levels in HEK-FAD cells enhances the production of human Aβ, whereas enhancing Cav-1 levels rescues this phenotype.

Third, we provide evidence that depletion of Cav-1 is sufficient to facilitate the amyloidogenic cleavage of APP, leading to increased production of Aβ and Aβ42 in particular. We show that the depletion of Cav-1 causes mislocalization of APP in the membrane. This shift may be the result of increased levels of APP and/or a change in its location in the membrane. Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that Cav-1 is necessary for the proper interaction of APP and its cleaving secretases, and that its depletion induces spatial conditions that promote the amyloidogenic cleavage.

One limitation of the db/db mouse model is the absence of human Aβ. While not fully understood, it is well documented that mouse Aβ does not exhibit the same pathological properties as its human counterpart. Because mouse Aβ does not aggregate, this model is inadequate for the assessment of the association between Cav-1 levels and amyloid deposition. Likewise, neurofibrillary tangles are not developed in all FAD mouse models that harbor endogenous WT tau. Future experiments should test the effect of Cav-1 depletion on the formation of amyloid deposition and neurofibrillary tangles by modulating Cav-1 levels in experimental models, such as induced pluripotent stem cells derived from AD patients. Nevertheless, increased tau phosphorylation in epitopes linked to AD pathology coincides with the depletion of Cav-1 in the db/db model of T2DM. Tau is phosphorylated by numerous protein kinases, such as glycogen synthase kinase-3β, cyclin-dependent kinase 5, protein kinase A (PKA), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Of particular interest is the relationship between PKA and MAPK with Cav-1. First, given that PKA is localized to caveolae and that the presence of the Cav-1 scaffolding domain is required for inhibition of PKA, perhaps loss of Cav-1 leads to increased activity of PKA, thus leading to the abnormal phosphorylation of tau (Razani and Lisanti, 2001b). Second, it is known that Cav-1 regulates the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway (Engelman et al., 1998; Okamoto et al., 1998). An important kinase in this pathway is MAPK, which could be abnormally active as a result of Cav-1 loss. Experiments designed to measure kinase activity as a direct result of Cav-1 loss would be informative. We further show that amyloid and tau pathology are accompanied by deficits in recognition memory in the diabetic mice. The ability of Cav-1 restoration to rescue learning and memory, and amyloidogenic processing, suggests a causative role for Cav-1 in the development of AD pathology in T2DM.

In conclusion, this work unravels a novel molecular mechanism underlying the development of cognitive deficits and AD-associated neuropathology in T2DM. This point of convergence between T2DM and AD may be a valuable target for future therapies aiming to improve cognition and attenuate the development of neuropathology and cognitive impairments in T2DM patients.

Footnotes

This work was supported by The National Institute on Aging AG060238, AG033570, AG033570-S2, AG062251, AG061628, and CCTS Pilot Grant 2017-06 to O.L., CCTS UL1TR002003, T32AG057468, and American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship to J.A.B., National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute RO1HL125356 to R.D.M. and M.G.B., and RO1AI131267 to M.G.B., and Alzheimer's Disease Research Center Grant AG05136. We thank Dr. Dirk Keene and The University of Washington for providing the human brain samples. We thank Drs. Carmela Abraham (Boston University) and Dennis Selkoe (Harvard Medical School) for the HEK cell lines expressing APPswe; and Dr. Peter Davies (Albert Einstein Institute) for the CP13, AT8, and DA9 antibodies.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Antunes M, Biala G (2012) The Novel Object Recognition memory: neurobiology, test procedure, and its modifications. Cogn Process 13:93–110. 10.1007/s10339-011-0430-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biessels GJ, Reagan LP (2015) Hippocampal insulin resistance and cognitive dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci 16:660–671. 10.1038/nrn4019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biessels GJ, Strachan MW, Visseren FL, Kappelle LJ, Whitmer RA (2014) Dementia and cognitive decline in type 2 diabetes and prediabetic stages: towards targeted interventions. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2:246–255. 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70088-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman JA, Chu C, Lin A, Jo H, Ikezu T, Okamoto T, Kohtz DS, Lisanti MP (1998) Caveolin-mediated regulation of signaling along the p42/44 MAP kinase cascade in vivo: a role for the caveolin-scaffolding domain. FEBS Lett 428:205–211. 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00470-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridolfsson HN, Roth DM, Insel PA, Patel HH (2014) Regulation of intracellular signaling and function by caveolin. FASEB J 28:3823–3831. 10.1096/fj.14-252320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudala K, Bansal D, Schifano F, Bhansali A (2013) Diabetes mellitus and risk of dementia: a meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. J Diabetes Investig 4:640–650. 10.1111/jdi.12087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head BP, Peart JN, Panneerselvam M, Yokoyama T, Pearn ML, Niesman IR, Bonds JA, Schilling JM, Miyanohara A, Headrick J, Ali SS, Roth DM, Patel PM, Patel HH (2010) Loss of caveolin-1 accelerates neurodegeneration and aging. PLoS One 5:e15697. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikezu T, Trapp BD, Song KS, Schlegel A, Lisanti MP, Okamoto T (1998) Caveolae, plasma membrane microdomains for alpha-secretase-mediated processing of the amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem 273:10485–10495. 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, Holtzman DM, Jagust W, Jessen F, Karlawish J, Liu E, Molinuevo JL, Montine T, Phelps C, Rankin KP, Rowe CC, Scheltens P, Siemers E, Snyder HM, Sperling R (2018) NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 14:535–562. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajoie P, Nabi IR (2010) Lipid rafts, caveolae, and their endocytosis. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 282:135–163. 10.1016/S1937-6448(10)82003-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastick CC, Saltiel AR (1997) Insulin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of caveolin is specific for the differentiated adipocyte phenotype in 3T3–L1 cells. J Biol Chem 272:20706–20714. 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastick CC, Brady MJ, Saltiel AR (1995) Insulin stimulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of caveolin. J Cell Biol 129:1523–1531. 10.1083/jcb.129.6.1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara T, Doi Y, Ninomiya T, Hirakawa Y, Hata J, Iwaki T, Kanba S, Kiyohara Y (2011) Glucose tolerance status and risk of dementia in the community: the Hisayama Study. Neurology 77:1126–1134. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822f0435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto T, Schlegel A, Scherer PE, Lisanti MP (1998) Caveolins, a family of scaffolding proteins for organizing “preassembled signaling complexes” at the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 273:5419–5422. 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razani B, Lisanti MP (2001a) Caveolins and caveolae: molecular and functional relationships. Exp Cell Res 271:36–44. 10.1006/excr.2001.5372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razani B, Lisanti MP (2001b) Two distinct caveolin-1 domains mediate the functional interaction of caveolin-1 with protein kinase A. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281:C1241–C1250. 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.4.C1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley M, Macauley SL, Holtzman DM (2016) Changes in insulin and insulin signaling in Alzheimer's disease: cause or consequence? J Exp Med 213:1375–1385. 10.1084/jem.20160493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MD, Montagne A, Sagare AP, Nation DA, Schneider LS, Chui HC, Harrington MG, Pa J, Law M, Wang DJ, Jacobs RE, Doubal FN, Ramirez J, Black SE, Nedergaard M, Benveniste H, Dichgans M, Iadecola C, Love S, Bath PM, et al. (2019) Vascular dysfunction: the disregarded partner of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 15:158–167. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.07.222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetrivel KS, Cheng H, Lin W, Sakurai T, Li T, Nukina N, Wong PC, Xu H, Thinakaran G (2004) Association of gamma-secretase with lipid rafts in post-Golgi and endosome membranes. J Biol Chem 279:44945–44954. 10.1074/jbc.M407986200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Wang AX, Liu Z, Chai W, Barrett EJ (2009) The trafficking/interaction of eNOS and caveolin-1 induced by insulin modulates endothelial nitric oxide production. Mol Endocrinol 23:1613–1623. 10.1210/me.2009-0115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Wang AX, Barrett EJ (2011) Caveolin-1 is required for vascular endothelial insulin uptake. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 300:E134–E144. 10.1152/ajpendo.00498.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]