Abstract

Background

The aim of the study is to determine whether there is a role of podoplanin and glutathione S‐transferases T1 (GST‐T1) expression in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

Methods

In this study, 33 patients were enrolled and gene expression analysis was performed by qRT–PCR. The podoplanin and GST‐T1 expression patterns were analyzed to determine their correlation with clinicopathologic parameters of laryngeal cancer.

Results

Of all included patients, 20 had supraglottic, and 13 had glottic laryngeal cancer. Increased expression of podoplanin was found in seven (35%) supraglottic tumor tissues and seven (53.8%) glottic tumor tissues, but GST‐T1 expression was not detected.

Conclusion

Podoplanin expression did not show any prediction for tumor differentiation, regional metastasis, thyroid cartilage invasion, lymphatic vessel invasion, or tumor differentiation for laryngeal cancer, and also there were no significant differences in podoplanin expression between glottic and supraglottic regions, but extracapsullar extension is almost statistically significance (P = 0.05).

Keywords: Podoplanin, GST‐T1, laryngeal carcinoma, biomarker, squamous cell carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Laryngeal cancer is the only cancer type among all malignancies for which the survival rate decreased in the last decade. Most of the laryngeal tumors are malignant and 95–98% are squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) 1. Human podoplanin gene, which consists of 162 amino acids, is a 38 kDA mucin‐type transmembrane glycoprotein and localized in 1p36.21. As podoplanin is expressed especially in lymphatic endothelial cells, it is not expressed in endothelium of blood vessels 2. Podoplanin is an intracellular protein that is reported to be expressed in lymphatic endothelium, alveolar type‐I cells, osteoblasts, and peritoneal mesothelial cells. It is not expressed in normal vascular endothelial cells 3, 4. Podoplanin also plays an important role in peripheral lung cell proliferation regulation and lymphatic vascular development. The podoplanin expression is upregulated in many different human cancers including squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity, lung, cervix, esophagus, and skin and also in dysgerminomas of the ovary and granulosa cell tumors, breast tumors, colorectal tumors, melanomas, mesotheliomas, and some tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) 5. Increased expression of podoplanin may cause a higher rate of lymph node metastasis. In addition, patients with lymph node metastasis and upregulated podoplanin expression had shorter disease‐specific survival rate than other patients. According to epidemiologic data, 25% of cases have regional and 8–10% have distant metastasis 6. Podoplanin is frequently expressed in cutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and may serve as a predictor for regional lymph node metastasis, locoregional recurrence, and clinical outcome 7. Neck metastasis is one of the most valuable prognostic factor of survival rate. Laryngeal SCC tumor stages and localizations may have different neck metastasis patterns. This may be due to the molecular structure and the biological behavior of the tumor. Regional metastasis may be related with lymphangiogenesis. Treatment varies according to the tumor stage and localization. Glottic cancers have better survival rates than supraglottic and subglottic cancers. Five‐year survival rates change between 65.7 and 88.6% 8, 9. The most common reason of mortality due to laryngeal SCC is the locoregional recurrence.

The glutathione S‐transferases (GSTs) is an important family of enzymes involved in phase‐II xenobiotic metabolism that catalyze biosynthesis and metabolism of many substances including detoxification of exogenous chemical carcinogens, such as aromatic polycyclic hydrocarbons present in tobacco 10. GST‐T1 enzyme, in GST‐T class with its gene is, located on chromosome 22q11.2 11. It has been shown that individuals carrying the null genotype of GST have significantly reduced activity of this antioxidant enzyme 12, 13 and so have higher levels of intermediates of oxidative metabolism. This genotype is related with many diseases 14. The revealed alterations in expression of GST‐T1 enzyme can cause activation of carcinogenic particles or extinction of toxic effects. Therefore, GST‐T1 enzyme can be used as an important biomarker for diagnosis of laryngeal cancer.

Thirty‐three patients (all males) with mean age ± SD of 58.03 ± 11.10 years, underwent histopathological examinations and total or partial laryngectomy operation with or without neck dissection in Istanbul University Faculty of Medicine Department of Otorhinolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, were included to the study (between November 2010 and November 2011). The patients who received primary other therapies, such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy, for laryngeal cancer were excluded. Tissue samples were obtained from both healthy adjacent mucosa and the tumor tissue itself during the surgery.

Total RNA was extracted from the tissue samples using Roche, High Pure RNA Tissue Kit (Cat. no. 12033674001 Roche, GmbH) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA samples were quantified using a NanoDrop® ND‐1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE). First strands of the cDNA samples were synthesized using RT PCR (Cat. no. 11483188001 Roche). The β‐Actin (ACTβ) gene was used as reference for normalization of the gene expression levels.

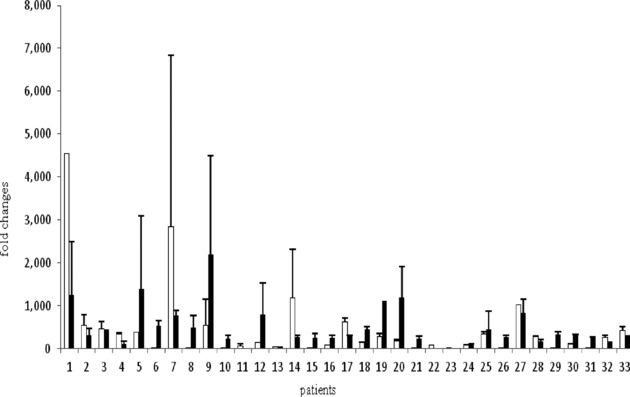

Podoplanin overexpression was found in 14 patients on the other hand, decreased podoplanin expression was found in 19 patients (Figure 1). Podoplanin expression did not show significant difference for tumor differentiation, regional metastasis, thyroid cartilage invasion, lymphatic vessel invasion, tumor stage tumor localization, N stage for laryngeal cancer, but extracapsullar extension was almost statistically significant (P = 0.05). The association between the patient characteristics and their podoplanin expressions is shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Podoplanin expression in laryngeal cancer patients.

Table 1.

Association Between Podoplanin Expression and Clinicopathological Data of Patients

| Podoplanin expression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downregule (n = 19) | Upregule (n = 14) | ||||

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % | P value |

| Age | 0.622 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 54.89 ± 11.18 | 62.28 ± 9.817 | |||

| Median | 55 | 61 | |||

| Smoking | 1.00a | ||||

| Yes | 18 | 58.1 | 13 | 41.9 | |

| No | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | |

| Alcohol | 0.561a | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 66.7 | |

| No | 18 | 60 | 12 | 40 | |

| Tumor differentiation | 0.948 | ||||

| Well | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | |

| Moderately | 17 | 58.6 | 12 | 41.1 | |

| Poorly | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | |

| Tumor localization | 0.284 | ||||

| Supraglottic tumor | 13 | 65 | 7 | 35 | |

| Glottic tumor | 6 | 46.2 | 7 | 53.8 | |

| Regional lymph node metastasis | 0.241a | ||||

| Yes | 7 | 77.8 | 2 | 22.2 | |

| No | 12 | 50 | 12 | 50 | |

| Tumor stage | 0.341 | ||||

| T1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | |

| T2 | 8 | 61.5 | 5 | 38.5 | |

| T3 | 8 | 66.7 | 4 | 33.3 | |

| T4 | 3 | 50 | 3 | 50 | |

| N stage | 0.416a | ||||

| N0 | 13 | 52 | 12 | 48 | |

| N1–3 | 6 | 75 | 2 | 25 | |

| Extra‐capsular spread of the lymph nodes | 0.05a | ||||

| Yes | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| No | 14 | 50 | 14 | 50 | |

| Thyroid cartilage invasion | 0.212 | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 40 | 6 | 60 | |

| No | 14 | 63.6 | 8 | 36.4 | |

| Lymphatic vessel invasion | 0.486 | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 66.7 | 4 | 33.3 | |

| No | 11 | 52.4 | 10 | 47.6 | |

Fisher's exact test.

These findings suggest that podoplanin plays a role in the progression of epithelial cancers. The physiological function of podoplanin is still uncertain. This situation inspires the investigators to find biological markers to predict the tumoral behavior. Podoplanin expression was investigated in intratumoral and peritumoral tissues of patients with tongue cancer. Rodrigo et al. found that podoplanin expression was related with regional metastasis, which is also supported by our study 15. However, any statistically significant difference about the tumor site was not found. Regional lymphatic metastasis was observed to be twofold higher in patients with low podoplanin expression level than in patients with high podoplanin expression level; but any statistically significant difference was not determined. Podoplanin expression levels vary considerably in dysplastic laryngeal epithelium tissue. Therefore, tissue culture should be observed in multiple regions instead of one region in some cases. Yuan et al. showed that patients, whose tumors expressed high levels of podoplanin, had a statistically significant higher rate of lymph node metastasis 6. In addition, patients with lymph node metastasis and increased podoplanin expressions had shorter disease‐specific survival rate than other patients. Kawaguchi et al. concluded that podoplanin was involved in oral tumorigenesis and may serve as a predictor for lymph node metastasis and poor clinical outcome 16. As known, the most prognostic factor of laryngeal cancers is regional lymphatic metastasis. Regional metastasis may be related with lymphangiogenesis. For this reason, we checked if podoplanin, expressed on lymphatic vessels but not on the capillary vessels, can be used for the prediction of regional metastasis. Podoplanin expression levels revealed that patients with a significantly poor prognosis in SCC of hypopharynx did not show a significant shorter survival in SCC of laryngeal. Rodrigo et al. showed that the expression of podoplanin in the dysplastic lesions was correlated with the risk of progression to laryngeal cancer 15. The exact molecular function of cancer cell expressing podoplanin is currently studied 17. Recent datas from studies of various human cancer types suggest a possible association of podoplanin expression with invasion and metastasis of tumors 18. Podoplanin expressions significantly decreased as the tumor classification levels increased. Therefore, it was proposed that the podoplanin expression may play a role at the initiation, but not in the progression, of laryngeal cancers. Moreover, no relationship was found between the podoplanin expression, the regional nodal metastasis, and tumor stage. In this study, extracapsullar extension is almost statistically significant (P = 0.05). It is well known that supraglottic and glottic compartments of the laryngeal cancer were developed from different embryologic origin. Glottic region carcinomas are generally well‐differentiated, supraglottic region carcinomas are moderate, and epidermoid carcinomas are poorly differentiated. Glottic region carcinoma spreads to anterior commissure with anterior extension, it also spreads to ventricular wall of supraglottic region with superior extension. Thus, extracapsular extension is an important marker for prognosis. Therefore, supraglottic area is rich in lymphatic vessels but glottic area has less lymphatic vessels. Rodrigo et al. showed higher levels of podoplanin expression in glottic carcinomas (P = 0.01) 15. On the other hand, in our study the increase of podoplanin expression was found to be higher in supraglottic carcinomas than in glottic carcinomas. The increase of podoplanin expression was obtained in early stages in patients with supraglottic carcinomas (35%) than in patients with glottic carcinomas (53.8%). The reason of the difference may be caused by the high levels of lymphatic duct's plexus localization in supraglottic carcinoma versus glottic carcinoma. Recent experimental results have demonstrated that podoplanin mediates a pathway leading to collective cell migration and invasion in vitro 19, 20. However, thyroid cartilage invasion depends directly on the primary tumor stage. In addition, extra capsular spreading of the nodal metastasis is related with tumor stage and survival rate.

Many biomarkers were found to determine the prognosis or metastatic disease of several malignancies, but no biological marker has been found for determination of the survival rate or metastatic disease for laryngeal cancer. GST‐T1 expression was not detected, increased expression of podoplanin was found in 14 tumor tissues; but there was no significant difference in podoplanin expression between tumor tissue and normal tissue.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No author of this paper has a conflict of interest, including specific financial interests, relationships, and/or affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials included in this manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the help of Ms. Allison Eronat and Ms. Kadriye Kahraman in executing this manuscript. We thank the Research Council of Istanbul University for supporting this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Manjarrez ME, Ocadiz R, Valle L, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus and relevant tumor suppressors and oncoproteins in laryngeal tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2006;23:6946–6951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Evangelou E, Kyzas PA, Trikalinos TA. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of lymphatic endothelium markers: Bayesian approach. Mod Pathol 2005;11:1490–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Naqvi J, Ordonez NG, Luna MA, Williams MD, Weber RS, El‐Naggar AK. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the head and neck: Role of podoplanin in the differential diagnosis. Head Neck Pathol 2008;1:25–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ordóñez NG. Podoplanin: A novel diagnostic immunohistochemical marker. Adv Anat Pathol 2006;2:83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kato Y, Kaneko M, Sata M, Fujita N, Tsuruo T, Osawa M. Enhanced expression of Aggrus (T1alpha/podoplanin), a platelet‐aggregation‐inducing factor in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol 2005;4:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yuan P, Temam S, El‐Naggar A, et al. Overexpression of podoplanin in oral cancer and its association with poor clinical outcome. Cancer 2006;3:563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kreppel M, Krakowezki A, Kreppel B, et al. Podoplanin expression in cutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma‐prognostic value and clinicopathologic implications. J Surg Oncol 2012. doi: 10.1002/jso.23238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bezerra de Souza DL, Jerez Roig J, Bernal MM. Laryngeal cancer survival in Zaragoza (Spain): A population‐based study. Clin Transl Oncol. 2012;3:221–224. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0787-1. PubMed PMID: 22374426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Cancer Institute . 2011. Surveillance Epidemyology and End Results. Updated November 10.

- 10. Vojtková J, Durdík P, Ciljaková M, Michnová Z, Turčan T, Babušíková E. The association between glutathione S‐transferase T1 and M1 gene polymorphisms and cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in Slovak adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications 2012. doi:pii: S1056 8727(12)00223–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zheng T, Holford TR, Zahm SH, et al. Cigarette smoking, glutathione‐s‐transferase M1 and t1 genetic polymorphisms, and breast cancer risk (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2002;7:637–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ye Z, Song H, Higgins JP, Pharoah P, Danesh J. Five glutathione s‐transferase gene variants in 23,452 cases of lung cancer and 30,397 controls: Meta‐analysis of 130 studies. PLoS Med. 2006;4:e91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Datta SK, Kumar V, Ahmed RS, Tripathi AK, Kalra OP, Banerjee BD. Effect of GSTM1 and GSTT1 double deletions in the development of oxidative stress in diabetic nephropathy patients. Indian J Biochem Biophys 2010;2:100–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Soya SS, Vinod T, Reddy KS, Gopalakrishnan S, Adithan C. Genetic polymorphisms of glutathione‐S‐transferase genes (GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1) and upper aerodigestive tract cancer risk among smokers, tobacco chewers and alcoholics in an Indian population. Eur J Cancer 2007;18:2698–2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rodrigo JP, García‐Carracedo D, González MV, Mancebo G, Fresno MF, García‐Pedrero J. Podoplanin expression in the development and progression of laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Mol Cancer 2010;9:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kawaguchi H, El‐Naggar AK, Papadimitrakopoulou V, et al. Podoplanin: A novel marker for oral cancer risk in patients with oral premalignancy. J Clin Oncol 2008;3:354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cueni LN, Chen L, Zhang H, et al. Podoplanin‐Fc reduces lymphatic vessel formation in vitro and in vivo and causes disseminated intravascular coagulation when transgenically expressed in the skin. Blood 2010;20:4376–4384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Raica M, Ribatti D, Mogoanta L, Cimpean AM, Ioanovici S. Podoplanin expression in advanced‐stage gastric carcinoma and prognostic value of lymphatic microvessel density. Neoplasma 2008;5:455–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cueni LN, Hegyi I, Shin JW, et al. Tumor lymphangiogenesis and metastasis to lymph nodes induced by cancer cell expression of podoplanin. Am J Pathol 2010;2:1004–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wicki A, Christofori G. The potential role of podoplanin in tumour invasion. Br J Cancer 2007;1:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]