Herpes simplex virus-1 encephalitis (HSVE) is the most common cause of fatal sporadic encephalitis worldwide. Recently, post-HSVE relapses due to autoimmune encephalitis with NMDA receptor antibodies and other synaptic autoantibodies have been reported in up to 27% of patients within 1–2 months after HSVE.1,2 We report an unusual case of a patient with refractory status epilepticus due to HSVE with antibodies against GABAA receptors (GABAAR).

Case report

A 47-year-old man was admitted with a new-onset generalized seizure. Two days before admission, behavioral changes were observed. No psychiatric symptoms, headaches, or feverish infections had occurred in the previous weeks. He had a B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma 5 years ago and a Hodgkin lymphoma 16 years ago, both in complete remission after radiochemotherapy. Eventually, focal status epilepticus developed provoking intensified anticonvulsive treatment.

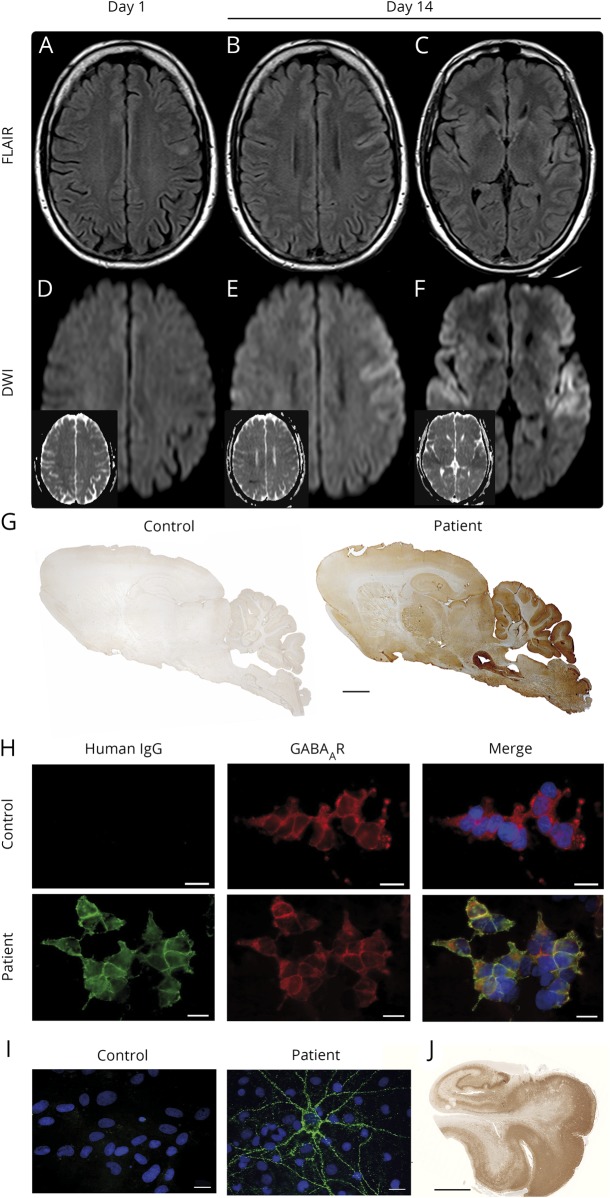

Initial brain MRI showed hyperintense fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal of the left prefrontal gyrus without diffusion restriction (figure 1, A and D) or contrast enhancement. CSF analysis on the day of admission revealed lymphocytic pleocytosis (13 leukocytes/μL), elevated protein (574 mg/L), and lactate (2.74 mmol/L). IV acyclovir 750 mg TID was started. CSF herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was negative. A second lumbar puncture (day 5 of admission) showed 29 lymphocytes/μL, normal protein, and slightly elevated lactate (2.27 mmol/L). HSV-1 DNA remained undetectable. Immunoglobulin G-HSV antibody index was unremarkable (<1.3); further analysis revealed no other infectious causes. However, GABAAR antibodies were detected in serum (1:1,600) and CSF (1:32) of the second lumbar puncture using cell-based assays, tissue-based assays, and life embryonal hippocampal neuron cultures (figure 1, G–I)3; no other neuronal antibodies were identified.

Figure. MRI findings and laboratory studies.

MRI 1st day of admission (A and D) and 14 days after admission (B, C, E, and F), showing progression of the left frontal hyperintense lesion and new diffusion restriction left frontally and bilaterally in the operculum on day 14. (A–C) Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery-weighted images with hyperintense lesion of the left prefrontal gyrus (A and B) and the operculum bilaterally (C). (D–F) Diffusion-weighted images and apparent diffusion coefficient images (small insets) without diffusion restriction (D) and marked diffusion restriction in the left prefrontal gyrus (E) and the operculum bilaterally (F). (G) Immunolabeling of sagittal rat brain sections with the patient's CSF antibodies showing a characteristic pattern. Patient and control CSF 1:4. Anti-human IgG (H + L). Human IgM and IgA did not show immunoreactivity. Scale bar 1 mm. (H) Detection of antibodies to the GABAA receptors (GABAAR) using HEK293 cell-based assay. Patient's but not control serum detects GABAAR. Human GABAAR subunits transfected into HEK293 cells and stained via life cell staining (serum 1:40). Green human IgG, red commercial GABAAR antibody. Scale bar 20 μm. (I) Patient's but not control serum detects neuronal surface antigens. Nonpermeabilized embryonic rat hippocampal neuron cultures DIV21 life cell stained with human IgG and nuclear counterstaining with DAPI (blue). Scale bar 20 μm. (J) Postmortem herpes simplex virus antigen staining of the patient's hippocampus. Scale bar 5 mm. DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; IgG = immunoglobulin G.

Acyclovir was stopped, yet IV methylprednisolone did not induce clinical improvement. Follow-up MRI showed expansion of the left frontal hyperintense FLAIR lesion with accompanied diffusion restriction and new bilateral opercular diffusion restrictions (figure 1, B, C, E, F). Refractory status epilepticus continued (EEG, figure e-1, links.lww.com/NXI/A145). The patient died of bowel ischemia due to thrombosis of the mesenteric artery. Postmortem revealed extensive HSVE with necrosis, inflammation, positive HSV antigen, and tissue PCR (figure 1J). No evidence of lymphoma was found.

Discussion

We describe an unusual case of CSF-qPCR-negative HSVE with concomitant GABAAR antibodies. We confirmed presence and specificity of GABAAR antibodies in serum and CSF with high titers, typical staining on rat brain immunohistochemistry and neuronal synapses of live neurons in vitro.

Our patient was initially misdiagnosed with idiopathic GABAAR encephalitis owing to detection of GABAAR antibodies, 2 negative HSV-1 qPCR in CSF, and characteristic clinical presentation with severe encephalitis and refractory status epilepticus.3,4 HSVE was only diagnosed postmortem by demonstration of widespread viral replication in brain tissue. Coincidental development of HSVE and GABAAR encephalitis is unlikely because of the low incidence of both diseases; rather breakdown of immunologic tolerance toward GABAAR likely provoked by virus-induced destruction of neurons would be a plausible explanation.5

Previous post-HSVE autoimmune encephalitis cases predominantly had a biphasic course. However, development in contiguity with HSVE symptoms similar to our case has been described in adults,1 and relapses have been observed as early as 7 days after HSVE in a 2-month-old boy.5

Furthermore, a case of post-HSVE GABAAR encephalitis was recently described in a 15-month-old child occurring 8 weeks after herpes infection, and a second case occurred following HHV6 encephalitis.4 We are not aware of a case of post-HSVE GABAAR encephalitis in an adult patient. However, because of the unavailability of initial CSF antibody testing, we cannot exclude the presence of “premorbid” GABAAR antibodies as a coincidental finding related to previous lymphoma. Although, the “premorbid” presence of high-titer CSF GABAAR antibodies without a history of seizures appears less plausible than our current hypothesis of continuous post-HSVE GABAAR encephalitis.

Pathologic-proven HSVE without detectable HSV-1 DNA in CSF is another unusual feature and was rarely reported.6,7 Hypothetical explanations could be early lumbar puncture and analysis under pretreatment with acyclovir. The previous lymphoma could have predisposed toward (1) the development of HSVE as has been noted in inborn errors of pattern-recognition pathways and (2) a breakdown of immune tolerance and consecutively development of systemic GABAAR antibodies predisposing to rapid development of CNS autoimmunity after HSVE.

In summary, this single case illustrates the occurrence of GABAAR antibodies in PCR-negative HSVE in an immunosuppressed patient resulting in misdiagnosis of idiopathic GABAAR encephalitis. Key clinical points are (1) the difficulty of ruling out HSVE with qPCR and immunoglobulin G antibody index, (2) the occurrence of GABAAR antibodies in parallel to HSVE, and (3) the possibility of unusual clinical courses of HSVE and post-HSVE autoimmune encephalitis in patients with immune deficiencies.

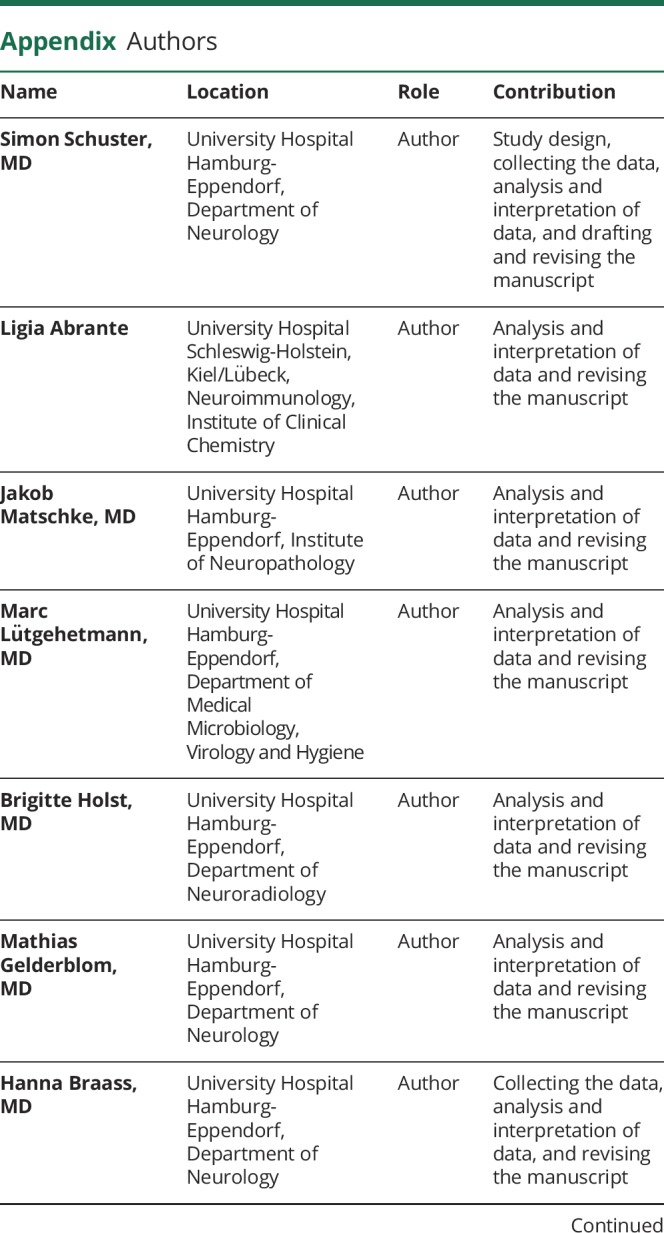

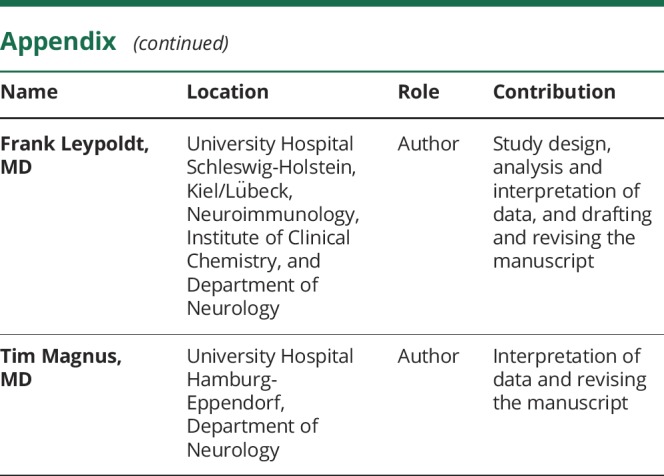

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

S. Schuster, L. Abrante, and J. Matschke report no conflict of interests. M. Lütgehetmann reports receiving speaker honoraria from Roche Diagnostics, DiaSorin, Swisslab, Abbott, and BioMerieux. B. Holst reports no conflict of interests. M. Gelderblom reports receiving personal fees from Allergan and Merz. H. Braass reports funding for travel from Boehringer Ingelheim. F. Leypoldt reports receiving speaker honoraria from Grifols, Teva, Fresenius, Roche, Merck, Bayer, Sanofi, and Novartis. He serves on a local advisory board for Roche and Biogen and works for an academic institution participating in commercial antibody testing. He does not receive personal reimbursements from this antibody testing. T. Magnus reports receiving personal fees from Merck Serono, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Novartis, Biogen, Grifols, and CSL-Behring and grants from the European Union (FP-7, ERA-NET), German Research Foundation, Schilling Foundation, and Werner-Otto Foundation. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Armangue T, Moris G, Cantarín-Extremera V, et al. . Autoimmune post-herpes simplex encephalitis of adults and teenagers. Neurology 2015;85:1736–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armangue T, Spatola M, Vlagea A, et al. . Frequency, symptoms, risk factors, and outcomes of autoimmune encephalitis after herpes simplex encephalitis: a prospective observational study and retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:760–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petit-Pedrol M, Armangue T, Peng X, et al. . Encephalitis with refractory seizures, status epilepticus, and antibodies to the GABAA receptor: a case series, characterisation of the antigen, and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:276–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spatola M, Petit-Pedrol M, Simabukuro MM, et al. . Investigations in GABAA receptor antibody-associated encephalitis. Neurology 2017;88:1012–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armangue T, Leypoldt F, Málaga I, et al. . Herpes simplex virus encephalitis is a trigger of brain autoimmunity. Ann Neurol 2014;75:317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adler AC, Kadimi S, Apaloo C, Marcu C. Herpes simplex encephalitis with two false-negative cerebrospinal fluid PCR tests and review of negative PCR results in the clinical setting. Case Rep Neurol 2011;3:172–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendez AA, Bosco A, Abdel-Wahed L, Palmer K, Jones KA, Killoran A. A fatal case of herpes simplex encephalitis with two false-negative polymerase chain reactions. Case Rep Neurol 2018;10:217–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]