Abstract

Purpose

Developmental language disorder (DLD), defined by low language performance despite otherwise normal development, can negatively impact children's social and academic outcomes. This study is the 1st to examine DLD in Vietnamese. To lay the foundation, we identified cases of DLD in Vietnam and explored language-specific characteristics of the disorder.

Method

Teacher ratings of 1,250 kindergarteners living in Hanoi, Vietnam, were used to recruit children with and without risk for DLD. One hundred four children completed direct measures of vocabulary and language sampling, and their parents completed in-depth surveys. We examined convergence and divergence across tasks to identify measures that could serve as reliable indicators of risk. Then, we compared performance on direct language measures across ability levels.

Results

There were positive associations between teacher and parent report and between report and direct language measures. Three groups were identified based on convergence across measures: DLD, some risk for DLD, and no risk. The DLD group performed lowest on measures of receptive and expressive vocabulary, mean length of utterance, and grammaticality. Although children with DLD exhibited a greater number of errors, the types of errors found were similar across DLD and No Risk groups.

Conclusions

Similar to rates found globally, 7% of the kindergarten population in Vietnam exhibited risk for DLD. Results highlight the importance of parent and teacher report and the value of multiple measures to identify DLD. We discuss potential clinical markers for DLD in the Vietnamese language and outline future directions.

Developmental language disorder (DLD; Bishop, Snowling, Thompson, Greenhalgh, & CATALISE-2 Consortium, 2017), also referred to as specific language impairment (Leonard, 2014) among other names, is defined as low language performance not secondary to obvious neurological, cognitive, or sensory impairment. Approximately 7% of kindergartners in the United States have DLD (Tomblin et al., 1997), with similar rates presumed globally. Children with DLD are four times more likely to develop reading problems (Catts, Fey, Tomblin, & Zhang, 2002) and are at risk for poorer academic and vocational attainment (Conti-Ramsden & Durkin, 2012). Early identification and intervention are needed to ameliorate long-term negative effects (Law, Garrett, & Nye, 2004).

Cross-linguistic research has shown that the relative strengths and weaknesses of children with DLD are influenced by the characteristics of the ambient language (Leonard, 2014). Features that are challenging for all learners of a given language are areas of particular weakness for children with DLD (Leonard, 2014). Much of the empirical literature on DLD has focused on English. However, there has been an increase in studies of DLD in Romance languages including Italian, Spanish, and French; Germanic languages including German, Dutch, and Swedish; Uralic languages including Hungarian and Finnish; and Sino-Tibetan languages including Mandarin and Cantonese (for a review, see Leonard, 2014). Recently, DLD has been studied in additional linguistic families, including Semitic languages (e.g., Friedmann & Novogrodsky, 2011) and Slavic languages (e.g., Vukovic & Stojanovik, 2011). Such work allows for the comparison of DLD across a range of typologies. Notably missing are languages from the Austroasiatic family.

Vietnamese is the most widely spoken Austroasiatic language and should be included among the languages in which DLD is described. In particular, Vietnamese combines a complex tonal system with analytic morphology. Vietnamese grammar primarily consists of word order and the use of particles that can change in function, depending on their clausal distribution (Duffield, 2017). Thus, it differs from other languages in the DLD literature, and it is of interest whether children show errors in tones, word order, or in the use of multifunctional particles. Adding a Vietnamese profile of DLD allows for further testing of theories of language and practical application. If we are to understand how to support Vietnamese-speaking children, both monolingual and bilingual, with and without DLD, we must first understand the language features of Vietnamese that are notably difficult for children to learn and then begin to use this information to differentiate typical development from impairment.

We undertake this study within the broader context of the state of the field in Vietnam and in the Vietnamese diaspora. In the United States, there are 1.5 million Vietnamese people, of whom nearly 400,000 are children (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Despite this growing population, fewer than 3% of speech-language pathologists are of Asian descent (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2017), and even fewer are familiar with the Vietnamese language and culture. Normative information is highly limited, and there are no standardized language assessments in Vietnamese.

In Vietnam, there is no college degree program in speech-language pathology, although clinical training is emerging with the support of international collaborations (Eitel, Tran, & Management Systems International, 2017). The related field of special education began in Vietnam in 1995, with the foundation of the Training and Development Center for Special Education at Hanoi National University of Education, followed by the establishment of the first college department of special education in 2001 at the same university (Kim, Kim, Le, & Hoang, 2013). To date, DLD is not a recognized disability in Vietnam. The first comprehensive law for persons with disabilities in Vietnam was passed in 2010 and recognized six types of disability: physical, hearing–speaking, visual, mental, intellectual, and other (Vietnam National Assembly, 2010). Whereas “hearing–speaking” (nghe và nói) is listed as a type of disability, this term most commonly refers to hard-of-hearing and deaf populations. Language disorders such as DLD are not mentioned. Indeed, there is much work to be done to raise public awareness about language disorders, train clinical practitioners, and build the research base on DLD in Vietnamese (Eitel et al., 2017). Here, we take the initial steps in constructing a knowledge base on Vietnamese DLD by focusing on identification.

Identifying Language Disorders

Children with DLD can be considered as falling on the low end of a language ability continuum when compared to same-age peers (Leonard, 1991, 2014). Poor language performance that goes beyond a certain point gives rise to a condition that is culturally devalued (Tomblin, 2006). That is, low language performance may not be considered problematic until there is a negative effect on a child's social well-being or academic attainment; classification of DLD at that point could lead to identification and appropriate treatment. Therefore, understanding how parents, educators, and care providers perceive whether a child is meeting environmental expectations is an integral part of defining what constitutes a language disorder in a given cultural context (Tomblin, 2006). Consistent with these conceptual frameworks of DLD (Leonard, 1991; Tomblin, 2006), identification depends on direct measures of a child's language skills, comparisons to peers, and measures of social evaluation.

Clinical practitioners and researchers alike rely on parent and teacher ratings, standardized assessments, and language sample analysis to identify children with DLD (Bishop et al., 2017). Particularly for languages in which there is limited information on normal acquisition and for which assessments have yet to be standardized, parent and teacher ratings paired with language sampling measures have been viewed as the gold standard for identification (e.g., Restrepo, 1998). Furthermore, the creation of standardized tests often begins with a multidimensional approach in which children are assessed in receptive and expressive modalities across language domains (e.g., Tomblin, Records, & Zhang, 1996).

Parent and Teacher Ratings

Parents and teachers are reliable reporters of children's language abilities (e.g., Bedore, Peña, Joyner, & Macken, 2011), and their reports should be included as part of clinical decision making (Bishop, Snowling, Thompson, Greenhalgh, & CATALISE Consortium, 2016). One specific measure of parent and teacher report is the Instrument to Assess Language Knowledge (ITALK), which is part of the Bilingual English–Spanish Assessment (Peña, Gutierrez-Clellen, Iglesias, Goldstein, & Bedore, 2014). The goal of the ITALK is to identify parent and teacher perception of a child's performance and to highlight areas of possible concern. In Bedore et al. (2011), teachers and parents rated children's language performance using the ITALK, and ratings were compared to performance on subtests of the Bilingual English–Spanish Assessment. Results revealed that both teacher and parent reports were significantly correlated to child language ability. Specifically, teacher ratings correlated with morphosyntax performance, whereas parent ratings correlated with their child's broad language performance.

Another tool, the Focus on the Outcomes of Communication Under Six (FOCUS; Thomas-Stonell, Oddson, Robertson, & Rosenbaum, 2010), is a survey measure that is available in many languages and is based on the World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework. This survey has demonstrated high internal consistency and construct validity in evaluating changes in English-speaking children's communication over time (Thomas-Stonell, Oddson, Robertson, & Rosenbaum, 2013), and validation studies are underway for other languages (e.g., Neumann, Salm, Rietz, & Stenneken, 2017).

It is worth noting that it may be easier for parents to report on children's current skills than to report retrospectively on early language milestones. One specific tool used to measure early milestones is Section A of the Alberta Language and Development Questionnaire (ALDeQ: Paradis, Emmerzael, & Duncan, 2010). The ALDeQ was originally designed for parents of children in the process of learning English as a second language in cases where it may not be feasible to measure children's first language directly. In a sample of 168 English language learners in Canada, aged 4–6 years, who spoke a variety of first languages, Paradis et al. (2010) found that the ALDeQ differentiated children with typical development from those with language impairment. Group differences on the two sections on early milestones and on current first language skills showed large effect sizes. The tool showed high specificity and poor sensitivity, suggesting that it could be used to identify children as typically developing but was less helpful in identifying DLD.

Results on the predictive value of early milestones in distinguishing between children with and without DLD have been mixed. In a retrospective study on early language milestones and DLD classification, Rudolph and Leonard (2016) found that all the children who had produced no words by 15 months of age and no two-word combinations by 24 months of age were later classified as having DLD in preschool. However, nearly half the sample of preschool children identified as having DLD (45%) showed no delays in early milestones. If a large proportion of children with DLD do not experience delays in early language development, the utility of early milestones as a report measure for DLD identification is questionable.

Assessments of Receptive and Expressive Language

Tomblin, Records, and Zhang (1996) developed a diagnostic system of DLD that employed standardized measures across three language domains (vocabulary, grammar, and narratives) and two modalities (comprehension and production) to form five composite scores. In their sample of 1,502 kindergarteners, children with DLD were operationally defined by two or more composite scores that were 1.25 SDs below the mean. Classification was then verified by speech-language pathologists who rated children's abilities on a severity rating scale, with 0 reflecting typical language and 4 representing severe language disorder. Notably, 77% of the children receiving severity ratings of 3 or 4 were diagnosed as having a language disorder using this diagnostic system of direct language measures, and 91% of children who received ratings of 0, 1, or 2 were identified as having typical language skills. Of course, such an undertaking requires valid and reliable standardized assessments and well-trained clinical practitioners, neither of which is readily available for Vietnamese. Nonetheless, we are able to emulate the approach of comparing performance across domains and modalities as a first step in our effort to diagnose DLD in Vietnamese-speaking children.

Language Sampling

Language sampling has become a vital component of child language assessments, particularly when standardized tests are not available and/or are regarded as inappropriate for a given population (e.g., Gutiérrez-Clellen, Restrepo, Bedore, Peña, & Anderson, 2000). In language sampling, a child's spontaneous language is collected in realistic settings (e.g., in conversation, storytelling, and play) to allow for the demonstration of functional communication skills. Dozens of measures can be generated from transcribed language samples using software programs such as Child Language Analysis (MacWhinney, 2000) or Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT; Miller & Iglesias, 2012).

At the sentence level, three language sampling measures that have been useful in distinguishing between children with and without DLD include mean length of utterance (MLU; e.g., Hewitt, Hammer, Yont, & Tomblin, 2005), subordination index (SI; e.g., Miller & Iglesias, 2012; Tsimpli, Peristeri, & Andreou, 2016), and grammaticality (Gram; e.g., Bedore, Peña, Gillam, & Ho, 2010). In English, MLU is calculated as the total number of morphemes divided by the total number of utterances to assess children's morphosyntactic development (Brown, 1973). However, for highly inflected languages such as Spanish, MLU in words is recommended for consistency across raters and comparability across languages (Gutiérrez-Clellen et al., 2000). Indeed, the basis for MLU calculation needs to reflect the characteristics of the language or language typology (see Vietnamese Language section below). SI is a measure of syntactic complexity and is calculated as the total number of clauses divided by the total number of utterances. SI has been used in the language acquisition literature to document complex sentence development (Loban, 1963) and, more recently, has been applied to bilingual children with and without DLD (e.g., Tsimpli et al., 2016). Gram, calculated as the number of grammatically correct utterances divided by the total number of utterances, has been positively associated with other language sampling measures such as MLU and has been used with bilingual children across ability levels (e.g., Bedore et al., 2010). Calculating Gram can also lead to an analysis of error patterns for a more in-depth language assessment (e.g., Ebert & Pham, 2017). Beyond the sentence level, language samples can be analyzed in terms of narrative or story structure. A variety of macrostructural measures have been employed to analyze children's storytelling skills. The Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives (MAIN; Gagarina et al., 2012), for example, is freely available in many languages, including Vietnamese. The MAIN includes picture stimuli, story models for retell, and a rubric to score for elements such as setting, internal state terms, and complete episodes (i.e., goal, attempt, and outcome). Story structure scores from the MAIN have been found to distinguish between typical and language-impaired groups across monolingual and bilingual children (Tsimpli et al., 2016).

Vietnamese Language and Related Research

Vietnamese is an isolating tonal language that uses a Romanized orthography (D. H. Nguyen, 1997). There are many mutually intelligible dialects spoken in the northern, central, and southern regions of Vietnam (for a review, see B. Phạm & McLeod, 2016). This study was conducted in Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam, where people speak either the Hanoi dialect or similar dialects from the northern region.

There continues to be disagreement among linguists and educators as to what constitutes a word in Vietnamese (e.g., Cao, 1988). For example, native speakers may consider a sequence of syllables that represents a single concept as either one or two words, for example, ham học [desire to-study] “studious” and đọc sách [read book] “read.” The syllable (i.e., tiếng/ âm tiết), on the other hand, is uncontroversial and widely agreed upon in Vietnamese because each individual syllable is separated by a space in the orthography. Therefore, measures of sentence length (e.g., MLU) calculated in syllables may resonate with native Vietnamese speakers more than words or morphemes.

Canonical sentence structure in Vietnamese is subject–verb–object. Subjects can be omitted particularly in conversation when the agent is understood (D. H. Nguyen, 1997). Compound sentences can be a string of simple sentences separated by commas; connectives are not required for a set of simple sentences to become a compound sentence (e.g., Tôi chạy, tôi nhảy, tôi múa [I run, I jump, I dance] “I run, I jump, (and) I dance”) but can be used to clarify the relation between simple sentences (e.g., D. H. Nguyen, 1997: Trời mưa, tôi ở nhà [Sky rain, I at home] “It's raining I am at home” can be clarified with a connective: Nếu trời mưa, (thì) tôi ở nhà “If it rains I will stay home”). Complex sentence structures in Vietnamese include embedding (e.g., Tôi nghĩ anh nói đúng [I think you-brother say correct] “I think you are right”) or relative clauses (e.g., Tôi thích bài thơ cô viết. [I like classifier-poem you-miss write.] “I like the poem you wrote”). Like compound sentences, complex sentences do not require conjunctions before relative clauses (e.g., mà, rằng “that”) in most cases (D. H. Nguyen, 1997).

One distinct feature of Vietnamese is the use of classifiers, namely, lexical items that precede nouns and indicate salient features of the noun such as animacy or shape (Tran, 2010). The number of classifiers in Vietnamese is debatable, from as few as three (Cao, 1988) to as many as 200 (D. H. Nguyen, 1957), primarily because words considered to be classifiers have been shown to have multiple meanings in actual language use (G. Pham & Kohnert, 2009). Although the number of classifiers may be uncertain, the use of classifiers in certain grammatical contexts is obligatory (Tran, 2010) such as following quantifiers within a noun phrase (e.g., ba con mèo [three animacy-classifier cat]).

Another feature of Vietnamese is the use of aspect markers that express the timing and progression of activities. There are preverbal markers that indicate anteriority (đã), progressive action (đang), or future reference (sẽ) and postverbal markers that express completion (e.g., xong, hết; for a review, see Phan, 2013). Vietnamese aspect markers are optional and can be omitted when the timing or progression of activities is understood in context (Duffield, 2017; Phan, 2013). The optionality of aspect markers may make their acquisition difficult (Tran & Deen, 2009), particularly among children with DLD (for a similar argument in Cantonese, see Fletcher, Leonard, Stokes, & Wong, 2005).

There are a limited number of studies on monolingual Vietnamese acquisition published in English (i.e., Tran, 2010; Tran & Deen, 2009) or in Vietnamese (e.g., Luu, 1996). Tran (2010) examined classifier acquisition using longitudinal and cross-sectional data from monolingual Vietnamese children aged 1–5 years. She found that animacy classifiers (i.e., con, cái) were acquired before the age of 2 years, and the most common error type was classifier omission. Tran and Deen (2009) examined aspect acquisition in the naturalistic speech of a toddler aged 1 year 9 months, in a total of 118 declarative utterances. They found that 45 verbs (38%) were marked for aspect but that the only aspect marker produced was the perfective marker (rồi); the three main aspect markers (đã, đang, sẽ) were not produced at all.

Luu (1996) examined vocabulary and grammatical development of preschoolers in Hanoi, Vietnam. She collected spontaneous utterances from 62 children, ages 2–6 years, during school interactions and diary entries for a total of over 98,000 utterances. Children in this study used an array of sentence types from a noun or noun phrase (i.e., phrase-level utterance) and simple sentences (i.e., subject–predicate) to expanded simple sentences (e.g., subject–predicate and relative clause) and complex sentences (e.g., main clause connected to a subordinating clause). On average, approximately 72% of the utterances produced were grammatically correct, a lower Gram score than reported from other language groups (e.g., > 80% for typically developing children in Restrepo, 1998); however, criteria for defining a correct versus incorrect utterance were not included, and it was unclear whether lexical–semantic errors were included in these percentages.

Alongside acquisition studies, the literature on disorders in Vietnam is developing. A handful of empirical studies published in Vietnamese has reported a wide range of prevalence rates for kindergarten children with speech-language problems. In a sample of 360 kindergarteners, A. Q. T. Nguyen (2017) reported that 30 children (8.3%) had speech-language problems based on a translated version of the Ages & Stages Questionnaires–Third Edition (Squires & Bricker, 2009). Using observational ratings of 200 kindergarteners from the Yen Bai province of Vietnam, Doan (2010) reported 8%–23% of children had problems in verbal expression and 10% of children had problems in language comprehension. Finally, a handful of recent papers published in Vietnamese have begun to recognize DLD (chậm phát triển ngôn ngữ đơn thuần; A. Q. T. Nguyen, 2017). However, these initial reports consist of descriptions of cases that include speech and language problems. Reported language profiles also seemed too severe and may have included confounding factors such as neurological or cognitive impairments. Furthermore, erroneous claims have been perpetuated, namely, that DLD is caused by poor educational environment and/or poor parenting (e.g., A. Q. T. Nguyen, 2017).

Although this emerging literature published in Vietnamese is important to recognize, several limitations are noted. These studies did not distinguish between speech versus language problems, nor do most studies distinguish between DLD and language disorders that are secondary to other conditions (e.g., intellectual disability). Studies have primarily relied on observational ratings (good, average, poor) rather than direct language measures, and rating scales often did not include scoring criteria. Furthermore, interrater reliability was not reported, nor was information on the raters' educational background and years of work experience. Clearly, much work remains to clarify misconceptions, distinguish between speech and language disorders, and systematically examine DLD in Vietnamese.

Study Purpose and Research Questions

The overall goals of this study were to identify cases of DLD in Vietnam and explore potential clinical markers for the Vietnamese language. There were three main research questions. The first question focused on the measures employed in the study. Because all measures were created or adapted for the Vietnamese language and culture, we first examined the convergence and divergence of these measures and how well they functioned to classify children as at risk or not for DLD. Specifically, we asked:

1.Is there convergence among parent report, teacher report, and direct language measures?

Based on studies in other languages, we anticipated positive associations between teacher and parent report and between report and direct language measures (e.g., Bedore et al., 2011; Restrepo, 1998). We anticipated that there would be a subset of children who would be detected by multiple measures and could be assigned with high confidence to the DLD group. There would also be a subset of children undetected by any measure, and this subset would become our minimal to no-risk group (i.e., No Risk). Finally, we anticipated that some children would be identified based on some measures (i.e., Some Risk) but would not meet criteria for DLD. Research Questions 2 and 3 relate to children's performance on the direct language measures:

2.How do the groups compare on direct language measures?

3.What types of errors do children with DLD make in Vietnamese?

We predicted that the DLD group would perform poorly on all language tasks in comparison to those in the No Risk and Some Risk groups. We anticipated that children with DLD in this study would produce shorter sentences, use more basic sentence structures, and produce fewer story elements in their narratives than their typical age-matched peers (e.g., Tsimpli et al., 2016). Similar to DLD studies in other languages, children with DLD may make a greater number of errors than their typical peers, but the types of errors may be similar across groups (Leonard, 2014). Based on the limited number of studies of Vietnamese language acquisition, potential areas of difficulty may include the production of classifiers (e.g., Tran, 2010) and aspect (e.g., Tran & Deen, 2009).

Method

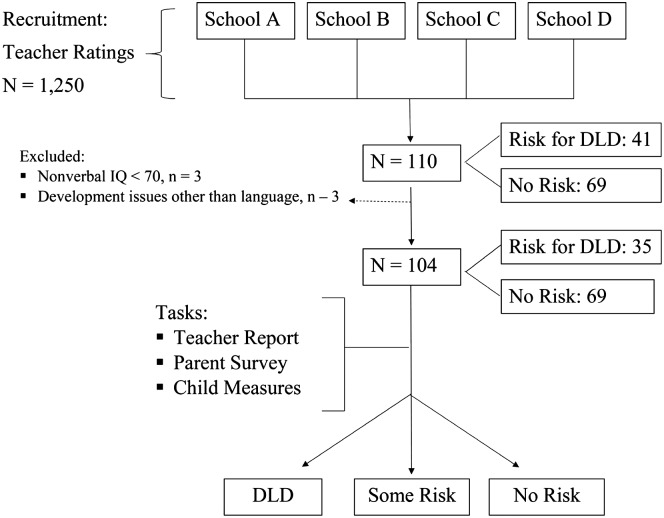

Figure 1 presents an overview of the project. We collaborated with teachers from four schools in Hanoi, Vietnam, to recruit participants from a pool of 1,250 kindergartners. Following our recruitment efforts, 110 children with and without risk for DLD and their parents completed a set of surveys and direct language measures. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the university of the first author and the collaborating university and kindergarten schools in Vietnam.

Figure 1.

Flow chart representing the steps of the study including recruitment, exclusionary criteria, assessment types, and classification into three groups: children with developmental language disorder (DLD), children with some level of risk for developmental language disorder (Some Risk), and children with no risk (No Risk; i.e., typically developing).

Survey Translation and Adaptation

This study included teacher and parent report measures that were available in English and were translated and adapted to the Vietnamese language with permission from the original authors. Translation procedures involved a three-step process. First, survey items were translated literally from English to Vietnamese and then back-translated into English again by two independent reviewers who were fluent in Vietnamese and had a college degree in speech-language pathology. Once literal translation accuracy was established, expert consultants reviewed survey items using a decentering process; items were reworded to ensure that the original constructs were conveyed in a culturally meaningful way (Peña, 2007). Expert consultants were educators living in Hanoi, Vietnam, with a college or graduate degree in special education, psychology, or related field and prior experience working with Vietnamese parents. Finally, survey items were retranslated back into English by a separate independent reviewer who was fluent in Vietnamese and had a graduate degree in speech-language pathology. Near-final translations in Vietnamese and in English were again reviewed by the first author to ensure that items remained faithful to the original English version and remained accessible to a Vietnam-based audience.

Recruitment Procedure

Children were recruited to participate in the study based on teacher report. Specifically, we translated and adapted the ITALK (Peña et al., 2014), which consisted of 5-point rating scales for the areas of speech, vocabulary, sentence production, grammar, and listening comprehension. Similar to the original ITALK, a brief definition of each language area was provided (e.g., Vốn từ là số lượng từ trẻ có thể hiểu và nói “Vocabulary is the amount of words children can understand and say”). Then, teachers were asked to rate the proficiency of the child in each area (e.g., for vocabulary, ratings were from 1 = Rất ít từ “very few words” to 5 = Vốn từ rất rộng “extensive vocabulary”). Finally, the teacher survey included a yes/no question (“Do you have any concerns about the child?”) and space to provide comments.

Surveys were completed in groups with all participating teachers from a given school in attendance. Teachers brought a class roster to the meeting and were instructed to assign each child an ID code. Forms were created to allow teachers to rate all students in their classroom in one language area at a time (e.g., speech) before proceeding to the next area (e.g., vocabulary). Teacher responses were later scanned into Remark Office OMR software (Gravic, 2015) to export for analysis.

Teachers also completed an exit survey to provide information about their teaching experience and confidence level for rating each language area. Based on exit survey data, teachers had completed 2–4 years of college education (M = 3.7 years). Teachers had an average of 6 years of teaching experience (range of 2–7 years or more) and 5 years of teaching kindergarten (range of 1–7 years or more). All teachers rated themselves as confident or very confident in completing each language area of the ITALK.

Using ITALK results, we recruited children based on the following operational criteria. First, we excluded children with severe speech problems, namely, those who were rated less than 3 out of 5 in the area of speech (e.g., When asked “Do you understand the child's speech?” teachers responded with 1 = never or 2 = rarely). Although DLD can co-occur with speech sound disorders (e.g., Shriberg, Tomblin, & Sweeney, 1999), this first step toward DLD identification in Vietnamese excluded children with low speech intelligibility. Then, we considered children to be at risk for DLD if they (a) were rated 3 or lower in at least two of the four remaining areas (listening comprehension, grammar, vocabulary, and sentence production) and (b) had a total mean score of less than 4.0 across all five areas. Once children at risk for DLD were selected, we identified typically developing children for recruitment from the same classrooms and of the same gender. Children who were rated 4 or 5 in all language areas of the ITALK and had no teacher concerns were considered typically developing, namely, at minimal to no risk for DLD.

Table 1 displays the number of children identified for No Risk and Risk for DLD groups. A total of 87 of 1,250 children (7.0%) were identified for the Risk group using our operational definition of ITALK scores. This percentage based on teacher report was consistent with prevalence rates of DLD in other languages such as English (Tomblin et al., 1997) that have been calculated using direct measures. Children were matched with No Risk peers, who were recruited at twice the rate (n = 133), to serve as a reference point of typical development. Teachers were provided recruitment packets with children's ID codes to distribute to parents. When parents provided written consent, teachers provided the child's identifying information (e.g., name, classroom) to the research team. Average response rate across schools was 50% (range: 45%–55%) with comparable response rates across No Risk and Risk groups.

Table 1.

Teacher ratings by school.

| Schools | A | B | C | D | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of classrooms | 6 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 23 |

| Kindergarten population | 364 | 380 | 361 | 145 | 1,250 |

| Average class size | 61 | 63 | 52 | 36 | 53 |

| No. of participating teachers | 12 (2/class) | 11 (~2/class) | 14 (2/class) | 4 | 41 |

| No. of risk for DLD (% of population) | 23 (6.3%) | 27 (7.1%) | 26 (7.2%) | 11 (7.5%) | 87 (7.0%) |

| Response rate (%) | 44.8 | 51.6 | 52.3 | 54.5 | 50.5 |

| Risk for DLD ITALK, M (range) | 3.16 (2.8–3.6) | 3.00 (1.4–3.4) | 3.15 (2.2–3.8) | 3.04 (2.8–3.4) | 3.09 (1.4–3.8) |

| No risk ITALK, M (range) | 4.80 (4.2–5.0) | 4.64 (4.0–5.0) | 4.79 (4.0–5.0) | 4.71 (4.2–5.0) | 4.75 (4.0–5.0) |

Note. Response rate is the percentage of recruited children whose parents agreed to participate in the study. DLD = developmental language disorder; ITALK = Instrument to Assess Language Knowledge Survey (Peña et al., 2014).

Participants

One hundred ten parents provided written consent, and 110 children provided written assent to participate in the study. Of the 110 children, there were 69 in the No Risk group and 41 in the Risk group (see Figure 1). Child participants completed the Primary Test of Nonverbal Intelligence (PTONI; Ehrler & McGhee, 2008) to measure nonverbal intelligence. This study included children with average to low average scores on the PTONI (i.e., standard scores ≥ 70; cf. American Psychiatric Association, 2013; see also CATALISE report, Bishop et al., 2016). We relied on parent and teacher report to exclude children with developmental concerns other than language (e.g., hearing loss, motor problems, frank neurological injury, autism). Based on this preliminary information, six children from the Risk group were excluded from the study. Three children were excluded due to low PTONI scores (< 70), and three children were excluded because either the teacher or parent had concerns for developmental problems other than language. There were 104 remaining child participants who completed direct language measures.

General Procedure

General procedures included teacher ratings, parent surveys, and child assessments. Teacher ratings were gathered using the ITALK, the measure used for participant recruitment. Parents returned written surveys to a research team member who would follow up by telephone to complete any missing or unclear items. Surveys were scanned into Remark Office OMR software (Gravic, 2015) to export data for analysis.

Individual children completed the study in a quiet area of the school. To maintain high reliability across testers, all audio stimuli were prerecorded by a female Vietnamese native speaker of the target (Hanoi) dialect. Children and research assistants listened simultaneously to the audio stimuli using headphones that were connected by a headphone splitter, and tasks were administered using a laptop. For the tasks in which children responded by pointing to pictures, picture stimuli were numbered, and research assistants entered children's responses using an external keypad. Keypad entries were entered directly using E-Prime 2.0 software (Schneider & Zuccoloto, 2007) and were later exported to Excel for analysis.

Five trained research assistants collected child data, and four additional research assistants collected parent surveys. All research assistants were native speakers of the northern Vietnamese dialect and had a college or graduate degree in education, special education, or related field. Data collection took place in Hanoi, Vietnam, over a 4-month time period in 2017, under the direct supervision of the first author.

Teacher Ratings

Teacher report was quantified using the ITALK. Originally, we applied operational criteria to the ITALK to recruit children with and without risk for DLD (see Recruitment Procedure). For the children who agreed to participate in the study, the dependent measure for teacher report was the mean across all five areas of speech, vocabulary, sentence production, grammar, and listening comprehension. Cronbach's alpha for the ITALK mean was .91, indicating excellent internal consistency.

Parent Survey

Family background information was gathered using a parent survey that included the language(s) spoken in the home, father and mother's level of education, and an estimate of socioeconomic status (SES). Parents in this study confirmed that no language other than or in addition to Vietnamese was regularly used in the home. SES was measured using the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (Adler & Stewart, 2007), a freely available measure that was designed to estimate SES in developing countries. Parents were provided a picture of a ladder with 10 rungs and were asked to mark an X in relation to where their family stands in comparison to others in Vietnam.

Survey results indicate that the majority of fathers (83%) and mothers (85%) had a college degree or higher. The majority of parents (66%) self-rated their SES as average compared to their country (i.e., 5 or 6 of 10); 18% of parents self-rated their SES as above average (i.e., 7–10), and 15% of parents self-rated their SES as below average (i.e., 1–4). It was noted that the percentage of parents with a college education in this sample was much higher than Vietnam's national average, which hovers at 12% in urban areas and 15% in the highest income bracket (Vietnam General Statistics Office, 2010). Kindergarten is part of the preschool education system in Vietnam and is not compulsory (Vietnam National Assembly, 2005). The sample of families that have the capacity to pay for kindergarten may not represent the average family in Vietnam in income or education.

Information on children's language history and current language skills was gathered using two parent report measures. First, we translated Section A of the Alberta Development and Language Questionnaire (Paradis et al., 2010) to measure early milestones (Milestones). A total of four items asked parents to report the approximate age in which their child started to walk, produced his or her first words, and combined two words in an utterance. The final item asked parents to compare the development of the target child to other children his or her age (e.g., slower or faster development). Using the scoring system outlined in Paradis et al. (2010), responses were scored using rating scales of up to 3 or 6 points per item. To illustrate, for Item 2 (the onset of first words), a score of 6 corresponded to responses that were < 15 months, a score of 4 corresponded to responses between 16 and 24 months, and responses of ≥ 25 months were scored as 0. The dependent measure was the proportion of given points out of 18, the total for the four items. Cronbach's alpha was .75, indicating acceptable internal consistency. For the second parent report measure, we translated and adapted the short version of the FOCUS (Thomas-Stonell et al., 2010) to measure children's current language skills. In 34 items, parents were asked to rate children's communication and interactions at home, school, and community settings using a 7-point rating scale. Cronbach's alpha was .95, indicating excellent internal consistency.

Child Measures

As part of the larger project, children completed three tasks: expressive vocabulary (ExpVoc), receptive vocabulary (RecVoc), and story retell.

ExpVoc

Children completed a picture-naming task to measure ExpVoc in which they were asked to label 60 pictures depicting objects. Picture stimuli consisted of black and white line drawings from the International Picture Naming Project (Szekely et al., 2004) and freely available line drawings from Google images. Items were selected from picture-naming tasks used with bilingual children who spoke Vietnamese and English (G. Pham & Kohnert, 2014) or Chinese and English (Sheng, Lu, & Kan, 2011). Using word frequency counts from the Corpora of Vietnamese Texts (G. Pham, Kohnert, & Carney, 2008), we selected items that ranged from low to high frequency. There were 12 items with high frequency (Ln = 6.43–8.80), 18 items with mid-high frequency (Ln = 4.17–5.90), 19 items with mid-low frequency (Ln = 1.95–3.97), and 11 items with low frequency (Ln = 0–1.79). The order of items was randomized, and children completed all 60 items of the task. Cronbach's alpha was .85, indicating good internal consistency.

RecVoc

Children completed a picture identification task to measure RecVoc in which they were presented with a 2 × 2 picture array, heard a word, and pointed to the corresponding picture. Picture stimuli were black and white line drawings from the International Picture Naming Project (Szekely et al., 2004) and free images from Google. Each array included the target word, a phonological foil, a semantic foil, and an unrelated foil. Sixty items were selected from a picture–word verification task previously used with Vietnamese–English bilingual children (G. Pham & Kohnert, 2014) and a picture identification task used with Chinese–English bilingual children (Sheng et al., 2011). Based on the Corpora of Vietnamese Texts (G. Pham et al., 2008), we selected 14 items with high frequency (Ln = 5.68–7.09), 16 items with mid-high frequency (Ln = 4.13–5.61), 20 items with mid-low frequency (Ln = 2.64–3.76), and 10 items with low frequency (Ln = 0.69–2.30). Items were randomized, and children completed all 60 items of the task. None of the items overlapped between ExpVoc and RecVoc tasks. Cronbach's alpha was .71, indicating acceptable internal consistency. Stimuli and record forms from both vocabulary tasks are available from the first author upon request.

Story Retell

Children completed the Cat Story from the MAIN (Gagarina et al., 2012). In this task, children were instructed to listen to a story and retell the story as close to the adult model as possible. Children listened to the prerecorded story along with the research assistant via headphones. They viewed a set of six pictures, whereas the research assistant pointed to the target picture for each portion of the story. Then, the child retold the story while viewing the pictures. Verbal prompting was limited to open-ended questions such as “What's next?” and “Tell me more.”

Stories were digitally audio-recorded and later transcribed using SALT software (Miller & Iglesias, 2012). Transcribers had either a college or graduate degree and were fluent in Vietnamese. Language samples were divided into modified communication units, which is recommended over conventional communication units when transcribing a language that permits subject omission (Miller & Iglesias, 2012) such as Vietnamese. Analysis excluded incomplete or unintelligible utterances, word or phrase repetitions, false starts, filler words, reformulations, and commentaries.

This task included a total of four dependent measures, three measures of sentence organization and one narrative measure. The three sentence-level measures were MLU, SI, and Gram. Recall that MLU was calculated based on syllables (see Vietnamese Language section) to be the average number of syllables per utterance. SI was calculated as the total number of clauses divided by the total number of modified c-units. Using the SI coding function in SALT (Miller & Iglesias, 2012), a trained research assistant determined the number of clauses for each modified c-unit. Following the SALT manual, utterances that were incomplete or that contained mazes or unintelligible words were excluded (i.e., SI = X). Utterances with omitted subjects in which the subject was unclear or utterances with an omitted main verb were included in SI calculations but were considered as not comprising a clause (i.e., SI = 0).

Consistent with scoring procedures by Bedore et al. (2010), Gram was calculated as the number of grammatically correct utterances divided by the total number of utterances. Unlike Bedore et al. (2010), there was no preset list of grammatical errors given the limited information on Vietnamese language development and disorders. Rather, utterances were judged as correct or incorrect by an expert rater, fluent in Vietnamese and English, with a master's degree in speech-language pathology. Incorrect utterances were then categorized by error type and verified by a second rater, fluent in Vietnamese, with a master's degree in speech-language pathology. Lexical errors including imprecise or incorrect word choice were excluded from Gram calculations. The fourth dependent measure from language sampling was story structure (Story). Consistent with procedures outlined by Gagarina et al. (2012), Story was scored using the MAIN rubric that allotted points for story elements (e.g., setting, episodes, internal states). The dependent measure was the number of story elements included, according to the rubric (maximum score of 17).

To ensure transcription accuracy, we followed procedures outlined in Ebert and Pham (2017) in which one research assistant transcribed samples and a second independent transcriber relistened to audio recordings and reviewed all transcripts for accuracy. Interrater reliability was calculated using 20% of the transcripts (22 language samples). Percent agreement between raters was 90.7% for modified c-units, 97.8% for Gram, 95.3% for SI, and 95.7% for Story scores.

Results

Convergence Across Measures

Research Question 1 examined convergence among the measures employed in the study. To address this question, we calculated bivariate Pearson correlations (see Table 2) and considered significant correlations less than .30 as small, between .30 and .50 as moderate, and greater than .50 as large (Cohen, 1988). Among the report measures, there was a moderate positive correlation between the ITALK and FOCUS (r = .46, p < .001), indicating good convergence between teacher and parent reports. There was a moderate correlation between the two parent report measures, FOCUS and Milestones (r = .30, p = .002). However, parent report of early milestones was not related to teacher report (Milestones and ITALK: r = .14, p = .17).

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations of teacher, parent, and child measures.

| Measure | ITALK | FOCUS | Milestones | ExpVoc | RecVoc | MLU | Gram | SI | Story |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITALK | — | .460** | .137 | .452** | .322** | .271** | .417** | .292** | .360** |

| FOCUS | — | .301** | .392** | .257** | .230* | .236* | .242* | .260** | |

| Milestones | — | −.002 | .056 | .101 | .092 | .050 | .044 | ||

| ExpVoc | — | .659** | .302** | .507** | .418** | .427** | |||

| RecVoc | — | .326** | .429** | .423** | .520** | ||||

| MLU | — | .572** | .768** | .405** | |||||

| Gram | — | .641** | .486** | ||||||

| SI | — | .593** | |||||||

| Story | — |

Note. Teachers completed the Instrument to Assess Language Knowledge (ITALK: Peña et al., 2014). Parents completed two measures: Focus on the Outcomes of Communication Under Six (FOCUS: Thomas-Stonell et al., 2010) and early language milestones (Milestones) from the Alberta Language and Development Questionnaire (Paradis et al., 2010). Children completed three tasks of expressive vocabulary (ExpVoc), receptive vocabulary (RecVoc), and story retell (Gagarina et al., 2012) that yielded four variables: mean length of utterance (MLU), grammaticality (Gram), subordination index (SI), and story structure (Story).*p < .05; **p < .01.

Regarding associations between report and direct measures, there were small to moderate correlations between all direct language measures and the ITALK (ranging from r = .27, p = .007 to r = .45, p < .001), indicating convergence between teacher report and child language measures. As anticipated, children whose language skills were rated high by teachers also performed well on the direct measures, whereas children whose language skills were rated low by teachers performed more poorly on direct measures. Similarly, there were small to moderate correlations between all direct measures and the FOCUS (ranging from r = .23, p = .02 to r = .39, p < .001), indicating convergence between parent report of children's current language skills and corresponding direct measures. In contrast, Milestones was not related to any direct measure, suggesting a disassociation between parents' report of early milestones and children's current language skills.

Among the direct language measures, ExpVoc and RecVoc were strongly related (r = .66, p < .001), indicating strong convergence between the vocabulary tasks. Similarly, the three grammatical measures (MLU, Gram, and SI) were strongly related (ranging from r = .57, p < .001 to r = .77, p < .001), indicating strong convergence between measures of sentence organization. Finally, performance on vocabulary tasks was moderately to strongly related to sentence-level performance (ranging from r = .30, p = .002 to r = .51, p < .001) and to story structure (ranging from r = .43, p < .001 to r = .52, p < .001).

Group Comparisons

A critical step in this initial study of Vietnamese language disorders was to identify cases of DLD. To this end, each dependent measure served as a potential risk indicator, and detection of risk was operationally defined as 1 SD or more below the sample mean. Children were classified as having DLD if they met three criteria: (a) detected by one or more report measures (i.e., parent and/or teacher concern); (b) detected by at least three of six direct language measures (ExpVoc, RecVoc, MLU, Gram, SI, and Story); and (c) the direct measures used for detection spanned at least two of three language domains of vocabulary, grammar, and narratives. Children who were not detected by any indicator were classified as typically developing (i.e., No Risk). Children detected by at least one indicator but who did not meet the criteria for DLD were considered to have some level of risk (i.e., Some Risk). Based on these operational criteria, 10 children were classified as having DLD, 49 children were classified as having Some Risk, and 45 children were classified as having No Risk.

Research Question 2 examined group differences on the direct language measures. To address this question, we first compared the three groups (DLD, Some Risk, and No Risk) on the independent variables using a multivariate analysis of variance omnibus test followed by pairwise comparisons with an Least Significant Difference adjustment. As shown in Table 3, the three groups differed on chronological age, F(2, 101) = 9.32, p < .001, ηp 2 = .16, and PTONI, F(2, 101) = 6.41, p = .002, ηp 2 = .11. Pairwise comparisons revealed that the No Risk group was older than the DLD group (d = 1.39) and the Some Risk group (d = 0.60) and that the Some Risk group was older than the DLD group (d = 0.81). Regarding nonverbal intelligence, the cutoff for this study was a standard score of 70 (cf. Bishop et al., 2016). The No Risk group had the highest score on the PTONI compared to the DLD group (d = 1.22) and the Some Risk group (d = 0.49). The Some Risk and DLD groups did not differ in PTONI scores (p = .08). We anticipated group differences on PTONI scores as children with DLD, as a group, have been found to score lower on nonverbal intelligence tests than their typically developing peers (e.g., Leonard et al., 2007). Nonverbal intelligence was considered part of the DLD profile (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Bishop et al., 2017) and was not statistically controlled for in this study.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics by participant group.

| Variables | Group |

Omnibus test |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLD n = 10 |

Some Risk n = 49 |

No Risk n = 45 |

Total N = 104 |

||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | p | |

| Age in months | 64.5a | 3.2 | 67.2b | 3.4 | 69.3c | 3.6 | 67.8 | 3.8 | < .001 |

| Girls/boys | 5/5 | 17/32 | 21/24 | 43/61 | .73 | ||||

| PTONI standard score | 87.0a | 10.8 | 97.8a | 15.9 | 106.8b | 20.4 | 100.7 | 18.5 | .002 |

| Father's education (6 max) | 3.8 | 1.1 | 4.1 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 1.0 | .71 |

| Mother's education (6 max) | 3.8 | 0.8 | 3.9 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | .79 |

| SES (10 max) | 5.7 | 1.6 | 5.4 | 1.4 | 5.8 | 1.3 | 5.5 | 1.4 | .32 |

Note. We used pairwise comparisons to compare groups (a, b, c). Father's and mother's education were each on a 7-point scale (0 = elementary school or less, 6 = doctoral degree). DLD = developmental language disorder; PTONI = Primary Test of Nonverbal Intelligence (Ehrler & McGhee, 2008); SES = socioeconomic status (cf. Adler & Stewart, 2007).

Because the groups differed in chronological age, we analyzed group differences on the dependent measures using a multivariate analysis of covariance omnibus test and with age as the covariate followed by pairwise comparisons with an Least Significant Difference adjustment. To examine the magnitude of group differences, we calculated effect sizes using Cohen's d and considered values of 0.20 as small, 0.50 as medium, and 0.80 as large (Cohen, 1988). As shown in Table 4, the three groups differed on two of three report measures, ITALK and FOCUS, with very large effect sizes between the DLD and No Risk groups (d = 2.64–5.11). For Milestones, the DLD group did not differ from the No Risk or Some Risk groups.

Table 4.

Group comparisons on dependent measures.

| Variables | Group |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLD |

Some Risk |

No Risk |

Total |

Cohen's d

|

|||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | DLD vs. No Risk | DLD vs. Some Risk | Some Risk vs. No Risk | |

| ITALK (max = 5) | 3.08a | 0.33 | 3.97b | 0.84 | 4.75c | 0.33 | 4.24 | 0.81 | 5.11 | 1.40 | 1.23 |

| FOCUS (max = 238) | 141.90a | 25.65 | 184.97b | 38.79 | 202.27c | 19.67 | 188.48 | 34.77 | 2.64 | 1.31 | 0.56 |

| Milestones | 0.91a | 0.09 | 0.85a, b | 0.25 | 0.95a, c | 0.09 | 0.90 | 0.19 | NA | NA | 0.52 |

| ExpVoc (max = 60) | 35.10a | 6.23 | 46.14b | 4.79 | 49.58c | 3.82 | 46.59 | 6.15 | 2.80 | 1.99 | 0.79 |

| RecVoc (max = 60) | 46.90a | 6.19 | 52.61b | 3.06 | 54.58c | 2.11 | 52.93 | 3.82 | 1.66 | 1.17 | 0.75 |

| MLU | 4.77a | 2.22 | 6.65b | 1.43 | 7.47c | 1.42 | 6.83 | 1.70 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 0.57 |

| Gram | 0.49a | 0.33 | 0.76b | 0.16 | 0.88c | 0.11 | 0.79 | 0.20 | 1.54 | 1.03 | 0.84 |

| Correct utterances | 4.80a | 3.39 | 8.77b | 3.97 | 12.96c | 3.78 | 10.27 | 4.67 | 2.27 | 1.08 | 1.08 |

| Total utterances | 9.80a | 3.91 | 11.52a | 4.68 | 14.80b | 4.08 | 12.84 | 4.69 | 1.25 | NA | 0.75 |

| SI | 0.71a | 0.42 | 1.13b | 0.18 | 1.24c | 0.15 | 1.14 | 0.25 | 1.66 | 1.30 | 0.63 |

| Story (max = 17) | 3.60a | 2.22 | 7.27b | 2.67 | 9.51c | 1.85 | 7.92 | 2.90 | 2.89 | 1.50 | 0.97 |

Note. Pairwise comparisons (a, b, c) were conducted following significant omnibus tests. Proportions are displayed for Milestones (out of 18), Gram, and SI. DLD = developmental language disorder; ITALK = Instrument to Assess Language Knowledge (Peña et al., 2014); FOCUS = Focus on the Outcomes of Communication Under Six (Thomas-Stonell et al., 2010); NA = not applicable; ExpVoc = expressive vocabulary; RecVoc = receptive vocabulary; MLU = mean length of utterance; Gram = grammaticality, calculated as the number of utterances without grammatical errors (i.e., correct utterances) divided by the total number of utterances (i.e., total utterances); SI = subordination index; Story = story structure (Gagarina et al., 2012).

The three groups differed on all direct language measures, with the DLD group performing the lowest and the No Risk group performing the highest. The largest differences were between the DLD and No Risk groups with very large effect sizes (d = 1.45–2.89), followed by the DLD and Some Risk groups with large to very large effect sizes (d = 1.01–1.99). The smallest group differences—although still medium to large in magnitude—were between the No Risk and Some Risk groups (d = 0.57–0.97).

To further examine group differences, we selected 10 children from the No Risk group and 10 children from the Some Risk group to match individual children with DLD in age (± 1 month) and gender. Figure 2 displays individual child profiles from the three groups to illustrate performance on all report and direct measures (displayed as z scores). As shown in Figure 2, children in the DLD group performed substantially lower than their age-matched peers in both Some Risk and No Risk groups. As anticipated, children in the No Risk group showed consistently high performance across measures. In contrast, profiles from the Some Risk group showed wide variability across measures; no single measure consistently showed low (or high) performance. We conducted a multivariate analysis of variance with this subset of participants, which yielded the same group differences found in the full sample: Children with DLD performed lower than those in the No Risk group on all measures (p values ranging from < .001 to .014), with the exception of Milestones (p = .15).

Figure 2.

Individual child profiles are displayed from the three groups of DLD (top), Some Risk (middle), and No Risk (bottom). Profiles consist of z scores from the three report measures (ITALK, FOCUS, and Milestones) and six direct measures (ExpVoc, RecVoc, MLU, Gram, SI, and Story). Profiles are displayed from youngest to oldest and are labeled by age (in months) and gender (M = male; F = female). Individual children from the Some Risk and No Risk groups were selected to match the individual DLD profiles by age (±1 month) and gender. DLD = developmental language disorder; ITALK = Instrument to Assess Language Knowledge; FOCUS = Focus on the Outcomes of Communication Under Six; ExpVoc = expressive vocabulary; RecVoc = receptive vocabulary; MLU = mean length of utterance; Gram = grammaticality; SI = subordination index; Story = story structure.

Error Patterns

Research Question 3 explored the number and types of errors produced by the DLD group as compared to their typical age-matched peers (i.e., No Risk group). As shown in Table 4, the DLD group produced a fewer number of grammatically correct utterances and a fewer total number of utterances, which resulted in a substantially lower Gram score (49%) than the No Risk group (88%). These scores corresponded to an average of 5.80 errors per child in the DLD group and 2.02 errors per child in the No Risk group.

Table 5 displays the types of errors produced by the DLD and No Risk groups and the percentage of each error type per group. Errors that occurred the most frequently for the DLD group were predicate omission, classifier omission, argument omission, and subject omission. Most frequent errors for the No Risk group were argument omission, classifier omission, and errors with word order. Aspect errors were not frequently found (≤ 2% across groups).

Table 5.

Error types produced by developmental language disorder (DLD) and No Risk groups.

| Error type | Example | % Errors |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| DLD | No Risk | ||

| Predicate omission | Child: Con mèo. Gloss: [Classifier-animacy cat] |

48 | 0 |

| Classifier omission | Child: Cậu bé làm rơi bóng. Correct: Cậu bé làm rơi quả bóng. Gloss: [Boy drop (missing classifier) balloon] |

31 | 35 |

| Argument omission | Child: Con mèo bắt. Gloss: [cat catch] |

7 | 43 |

| Subject omission | Child: Sau đó lấy được quả bóng. Correct: Sau đó cậu bé lấy được quả bóng. Gloss: [Afterwards (boy) take able-to classifier + balloon] |

7 | 4 |

| Preposition omission | Child: Con mèo bị ngã cây. Correct: Con mèo bị ngã vào bụi cây Gloss: [Cat fall into shrub] |

3 | 1 |

| Clause omission | Child: Khi cậu bé lấy được quả bóng. Gloss: [When boy take able-to classifier + balloon] |

2 | 6 |

| Aspect error | Child: Cậu bé đang câu cá xong. Gloss: [Boy aspect-progressive fish aspect-completed]. Correct: Cậu bé đã câu cá xong. Gloss: [Boy aspect-anteriority fish aspect-completed] |

2 | 0 |

| Word order | Child: Cậu bé đến nỗi giật mình rơi quả bóng. Correct: Cậu bé giật mình đến nỗi rơi quả bóng. Gloss: [Boy shocked to-point-of drop classifier + balloon] |

0 | 7 |

| Classifier commission | Child: Ăn một cái cá. Correct: Ăn một con cá. Glass: [Eat one animate classifier fish.] |

0 | 4 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | |

Note. Examples include a child's utterance in Vietnamese (Child), the adult target when applicable (Correct), and the literal translation to English (Gloss). Target grammatical features are in bold when applicable. Percentages of errors were calculated for each group separately.

One error type that occurred in the DLD group but not in the No Risk group was predicate omission. Although predicate omission comprised 48% of total errors in the DLD group, this error was exhibited by three children who labeled pictures instead of retelling stories. Despite listening to the model and confirming that they understood the instructions, these children produced utterances that consisted of a noun or noun phrase (e.g., Con mèo [classifier-animacy cat ] “A cat”). An error type that occurred in both groups but with low frequency (7% or less) was subject omission. Although subject omission is permissible in Vietnamese when the agent is known (D. H. Nguyen, 1997), subject omission errors occurred when the subject had not been introduced, making it difficult to understand which character(s) were involved.

Two error types that occurred in the No Risk group that were not found in the DLD group were word order and classifier commission. As shown in Table 5, errors of word order occurred when children were attempting to make a complex sentence using an embedded clause. Because children with DLD produced simple sentences (see SI scores in Table 4), their utterances may not have afforded the opportunity to make this type of error. Classifier commission occurred when children produced the inanimate classifier (cái) instead of the animate classifier (con). Children with DLD omitted classifiers rather than substituting one classifier for another. Two error types that were frequently produced by both groups (> 30% of total errors) were classifier omission and argument omission. These two errors are further evaluated in the Discussion section.

Discussion

This initial effort to identify DLD in the Vietnamese language has established a number of important phenomena:

In Vietnamese as in other languages studied so far, about 7% of kindergarten children were classified as at risk for DLD.

Parents and teachers are reliable reporters of children's language skills.

An array of direct and report measures is helpful in distinguishing children with DLD from their typically developing peers. An intermediate group, which may include children at some risk or may simply be misidentified, also exists.

Vietnamese children with DLD produce similar types of grammatical errors as their typically developing peers but with greater frequency.

In order to identify cases of DLD in Vietnam, we began with teacher ratings of 1,250 kindergartners in Hanoi, Vietnam. Children who were rated low in two or more language areas were considered at risk for DLD. An average of 7% of the kindergarten population met these criteria with a range of 6.3%–7.5% per school (see Table 1). Because kindergarten is not compulsory in Vietnam (Vietnam National Assembly, 2005), our estimate might be conservative as it does not include representation from 5-year-olds in Vietnam who are not enrolled in kindergarten. In addition, given the comorbidity of speech sound disorders and DLD (e.g., Shriberg et al., 1999), the prevalence of DLD in Vietnam might be higher than our estimate because we excluded children who were rated as having extremely low speech intelligibility. Nonetheless, it is notable that an empirically driven approach using teacher report with no a priori target yielded a percentage of risk for DLD that is highly consistent with estimates of DLD in kindergarten populations worldwide (e.g., Tomblin et al., 1997).

Parents and teachers are reliable sources of information on children's language skills due to their regular interactions with children across naturalistic contexts (Bishop et al., 2016). In our results, we found general agreement between parent and teacher reports and between report and direct measures. Notably, the Vietnamese adaptations of the FOCUS and ITALK that were created for this study had high internal consistency and were effective in gathering systematic input from parents and teachers.

Previous studies of DLD in kindergarten children have prioritized parent report over teacher report (e.g., Bedore et al., 2011). However, teachers may be a more reliable source of information in the context of Vietnam. Because kindergarten is part of the preschool educational system that includes all-day day care and educational programming for children, ages 2–5 years (Vietnam National Assembly, 2005), participants in this study attended school 5 days a week from approximately 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Kindergarten teachers in Vietnam may be keen reporters because they have many opportunities to observe and interact with children in various activities throughout the day. This experience with a large number of children of the same age may enable teachers to accurately rate children's language skills in comparison to their peers.

Notably, we found that the parent report measure of early milestones (Milestones) diverged from other indicators. Although the two parent report measures (FOCUS and Milestones) were moderately related (see Table 2), Milestones was not related to teacher report (ITALK), nor to any direct language measure. In contrast to previous studies (e.g., Paradis et al., 2010), early milestones did not distinguish between groups of children with and without DLD in this sample (see Table 4). There are at least two potential reasons for this finding. First, Rudolph and Leonard (2016) suggested that the type of milestone matters and that late production of word combinations had more predictive value for DLD identification than late production of first words. Another explanation for these results might be related to cultural differences. It remains an open question whether the timing of early milestones is salient for Vietnamese parents. In addition, first words and combinations can be defined differently across cultures, particularly when the concept of a Vietnamese word continues to be debated (see the Vietnamese Language and Related Research section). Further study is needed, perhaps using qualitative or mixed methods, to better understand how questions about early milestones are interpreted and answered in the Vietnamese culture.

The classification process employed in this study included multiple report and direct language measures to reflect a multidimensional approach to assessment (e.g., Tomblin et al., 1996). As a first step in the exploration of DLD in Vietnamese, we used a cutoff of 1 SD below the mean, and children were classified as having DLD if they had teacher and/or parent concern and low performance on at least three direct language measures that spanned two or more domains of vocabulary, grammar, and narratives.

When comparing across groups, there were large differences between children with and without DLD. As shown in Table 4, children in the DLD group produced shorter stories as measured by fewer utterances (Total Utterances) and shorter utterance length (MLU) than children in the No Risk group. Furthermore, utterances produced by the DLD group were often incomplete (see Table 5 for error types) and consisted of less than one clause (SI = 0.71), whereas an average utterance produced by the No Risk group consisted of at least one main clause and, at times, a subordinate clause (SI = 1.24).

Clearly, the work reported here can make no incontrovertible claims about child classifications. Further study is needed to refine measures and empirically derive cutoffs to calculate diagnostic accuracy (Spaulding, Plante, & Farinella, 2006). In addition, future studies will examine longitudinal data with this cohort. Following these groups over time will confirm whether those classified here as DLD or No Risk indeed follow consistently different developmental trajectories.

In the classification process, we found a large number of children who could not be neatly placed into DLD or No Risk groups (i.e., Some Risk). As shown in Figure 2, children in the Some Risk group showed mixed profiles of performance across measures. The presence of this intermediate group supports the notion that children fall on a language ability continuum and that children with DLD are at the extreme low end (Leonard, 1991). Follow-up data are needed to establish whether children in the Some Risk group show intermediate growth patterns that fall between the other two groups or greater within-group heterogeneity, with some children moving into the DLD group and others catching up with the No Risk group. The fact that the Some Risk group scores between the DLD and the No Risk groups on all dependent measures (see Table 4) and that the standard deviations in that group are not greater than in the other two groups suggests that they might represent a mildly impaired sample, again confirming the difficulty of drawing firm boundaries between children who have DLD and those who do not (Leonard, 1991, 2014).

In general, children with and without DLD exhibited similar types of errors, and the frequency of errors varied across groups (see Table 5). This result is consistent with cross-linguistic work that has shown that features in a given language that are difficult for all children are especially challenging for children with DLD (Leonard, 2014; although for qualitative differences, see Hansson & Nettelbladt, 1995; Van der Lely & Ullman, 2001). Two frequent error types shared across No Risk and DLD groups were classifier omission and argument omission. Argument omission occurred at a greater proportion in the No Risk group than in the DLD group (43% vs. 7% of total errors/group). Children in the No Risk group may have produced a larger proportion of argument errors because they were using a larger variety of verbs, particularly verbs that require objects. A smaller proportion of argument errors in the DLD group may reflect a limited use of verb types rather than a more sophisticated grammatical system. It should be noted that the spontaneous language samples analyzed here may not have provided adequate opportunity for children to produce complex syntactic structures. For example, one grammatical feature that children rarely used in retelling stories was aspect markers. Given the optionality of aspect markers in Vietnamese (D. H. Nguyen, 1997) and their limited spontaneous production in early acquisition (Tran & Deen, 2009), future studies that include specific probes may be needed to capture aspect use (see Fletcher et al., 2005, for exemplar tasks in Cantonese).

One error type that has the potential to be a clinical marker in Vietnamese is classifier omission, which comprised over 30% of total errors in DLD and No Risk groups alike. Errors with classifiers have been found among typically developing Vietnamese children, with relatively more errors with omission than substitution (Tran, 2010). Similar to studies of DLD in other languages (Leonard, 2014), Vietnamese children with DLD may experience a prolonged stage of making errors with classifiers as compared to age-matched peers. Further analysis is needed to examine whether classifier omission persists among children with DLD over time.

To conclude, the collective effort presented here is the first step of many to investigate DLD in Vietnamese. Longitudinal goals of this project include measuring growth trajectories over time and connecting language to literacy in Vietnamese children with and without DLD. Overall findings from this series of studies will contribute to building a framework for DLD identification and to refining language assessment tools for Vietnamese, a language still greatly underrepresented in the empirical literature.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant K23DC014750, awarded to the first author. Portions of this article were presented at the 2017 American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Convention in Los Angeles, California. We acknowledge the child assessors and staff at Hanoi National University of Education Training and Development Center for Special Education: Net Ho, Khoi Lang, Chinh Le, Mai Nguyen, Sinh Pham, Van Pham, and Yen Hai Pham; San Diego State University Bilingual Development in Context Research Laboratory members: Jessica Abalos, Kristine Thuy Dinh, Ngoc Anh Do, Judit Limon Hernandez, KimAnh Nguyen, Tina Nguyen, Harsh, and Christine Melcher; San Diego State University technical support: Brian Lenz, Wesley Quach, Zena Hovda, and Marlo Martinez; and collaborating schools, principals, teachers, parents, and children.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant K23DC014750, awarded to the first author. Portions of this article were presented at the 2017 American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Convention in Los Angeles, California.

References

- Adler N., & Stewart J. (2007). The MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status. MacArthur Research Network on SES & Health. Retrieved from http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/research/psychosocial/subjective.php

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2017). ASHA summary membership and affiliation counts, year-end, 2016 Retrieved from http://www.asha.org [Google Scholar]

- Bedore L. M., Peña E. D., Gillam R. B., & Ho T.-H. (2010). Language sample measures and language ability in Spanish–English bilingual kindergarteners. Journal of Communication Disorders, 43, 498–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedore L. M., Peña E. D., Joyner D., & Macken C. (2011). Parent and teacher rating of bilingual language proficiency and language development concerns. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 14, 489–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D. V., Snowling M. J., Thompson P. A., Greenhalgh T., & CATALISE Consortium. (2016). CATALISE: A multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study. Identifying language impairments in children. PLOS ONE, e0158753, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D. V., Snowling M. J., Thompson P. A., Greenhalgh T., & CATALISE-2 Consortium. (2017). Phase 2 of CATALISE: A multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58, 1068–1080. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. (1973). A first language: The early stages. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cao X. H. (1988). The count/mass distinction in Vietnamese and the concept of “classifier.” STUF–Language Typology and Universals, 41, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Catts H. W., Fey M. E., Tomblin J. B., & Zhang X. (2002). A longitudinal investigation of reading outcomes in children with language impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 45, 1142–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analyses for the social sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Conti-Ramsden G., & Durkin K. (2012). Postschool educational and employment experiences of young people with specific language impairment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 43, 507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan P. T. (2010). Thực Trạng phát triển ngôn ngữ của trẻ 5–6 tuổi tại tỉnh Yên Bái [Language development of children 5–6 years old in Yen Bai province] (Unpublished master's thesis). Viện khoa học giáo dục Việt Nam. [Google Scholar]

- Duffield N. (2017). On what projects in Vietnamese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics, 26, 351–387. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert K. D., & Pham G. (2017). Synthesizing information from language samples and standardized tests in school-age bilingual assessment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 48, 42–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrler D., & McGhee R. (2008). Primary Test of Nonverbal Intelligence (PTONI). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Eitel S., Tran H. V., & Management Systems International. (2017). Speech and language therapy assessment in Vietnam. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID): Vietnam Evaluation, Monitoring and Survey Services Project (VEMSS). Retrieved from https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00MJHP.pdf

- Fletcher P., Leonard L. B., Stokes S. F., & Wong A. M. (2005). The expression of aspect in Cantonese-speaking children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48, 621–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann N., & Novogrodsky R. (2011). Which questions are most difficult to understand?: The comprehension of Wh questions in three subtypes of SLI. Lingua, 121, 367–382. [Google Scholar]

- Gagarina N., Klop D., Kunnari S., Tantele K., Välimaa T., Balčiūnienė I., … Walters J. (2012). Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives (MAIN). In ZAS papers in linguistics (p. 56). Retrieved from http://www.zas.gwz-berlin.de/zaspil56.html

- Gravic. (2015). Remark office OMR [Computer software]. Malvern, PA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Clellen V. F., Restrepo M. A., Bedore L., Peña E., & Anderson R. (2000). Language sample analysis in Spanish-speaking children: Methodological considerations. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 31, 88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson K., & Nettelbladt U. (1995). Grammatical characteristics of Swedish children with SLI. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 38, 589–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt L. E., Hammer C. S., Yont K. M., & Tomblin J. B. (2005). Language sampling for kindergarten children with and without SLI: Mean length of utterance, IPSYN and NDW. Journal of Communication Disorders, 38, 197–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. Y., Kim H. G., Le T. M. H., & Hoang T. N. (2013). Giáo dục đặc biệt: Lịch sử và sự phát triển [Special education: History and development]. In Chung D. Y. & Le T. M. H. (Eds.), Nhập môn giáo dục đặc biệt [Introducing special education] (pp. 15–47). Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam: University of Pedagogy Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Law J., Garrett Z., & Nye C. (2004). The efficacy of treatment for children with developmental speech and language delay/disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 47, 924–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]