Abstract

Purpose

Although there is increasing interest in using structural priming as a means to ameliorate grammatical encoding deficits in persons with aphasia (PWAs), little is known about the precise mechanisms of structural priming that are associated with robust and enduring effects in PWAs. Two dialogue-like comprehension-to-production priming experiments investigated whether lexically independent (abstract structural) priming and/or lexically (verb) specific priming yields immediate and longer, lasting facilitation of syntactic production in PWAs.

Method

Seventeen PWAs and 20 healthy older adults participated in a collaborative picture-matching task where participant and experimenter took turns describing picture cards using transitive and dative sentences. In Experiment 1, a target was elicited immediately following a prime. In Experiment 2, 2 unrelated utterances intervened between a prime and target, thereby allowing us to examine lasting priming effects. In both experiments, the verb was repeated for half of the prime–target pairs to examine the lexical (verb) boost on priming.

Results

Healthy older adults demonstrated abstract priming in both transitives and datives not only in the immediate (Experiment 1) but also in the lasting (Experiment 2) priming condition. They also showed significantly enhanced priming by verb overlap (lexical boost) in transitives during immediate priming. PWAs demonstrated abstract priming in transitives in both immediate and lasting priming conditions. However, the magnitude of priming was not enhanced by verb overlap.

Conclusions

Abstract structural priming, but not lexically specific priming, is associated with reliable and lasting facilitation of message–structure mapping in aphasia. The findings also suggest that implicit syntactic learning via a dialogue-like comprehension-to-production task remains preserved in aphasia.

Decades of psycholinguistic research have established that structural priming—a speaker's tendency to echo previously encountered (heard or produced) message–structure associations—is pervasive in unimpaired speakers, reflecting cognitive processes that support efficient language processing and the mechanisms of language learning (Chang, Dell, & Bock, 2006; Ferreira & Bock, 2006; Mahowald, James, Futrell, & Gibson, 2016; Pickering & Ferreira, 2008). There is a growing interest in studying structural priming as a means to ameliorate impaired grammatical encoding processes in persons with aphasia (PWAs). As yet, little is known about the precise mechanisms of structural priming that are associated with robust and/or enduring effects in PWAs. This study aims to address this significant gap by investigating the effects of verb overlap on immediate and lasting structural priming in a dialogue-like comprehension-to-production priming task.

Structural priming is multifactorial in normal language processing, modulated by various factors. Earlier studies have identified that the locus of priming is at the level of abstract structural representations dictating the order of sentential constituents, independent of lexical–semantic content (i.e., abstract priming, henceforth; Bock, 1989; Bock & Loebell, 1990). For example, speakers are equally likely to produce passive structures (the mailman was chased by a dog) whether primed with a passive construction (the man was struck by lightning) or a sentence with a locative prepositional phrase (the man drove the car to the office). This indicates that the phrasal combinatorial nodes of a prime are sufficient to bias future production preferences in speakers, even in the absence of shared lexical–semantic content between prime and target (Bock & Loebell, 1990). However, later studies have shown that structural priming implicates levels of nonsyntactic representations, such as lexical items (e.g., Hartsuiker, Bernolet, Schoonbaert, Speybroeck, & Vanderelst, 2008; Pickering & Branigan, 1998; Scheepers, Raffray, & Myachykov, 2017) and event semantic content (Gruberg, Ostrand, Momma, & Ferreira, 2019; Gruberg, Wardlow, & Ferreira, 2019; Lee, Man, Ferreira, & Gruberg, 2019, for aphasic data).

Most relevant to the current study, a body of literature clearly demonstrates that the magnitude of priming becomes significantly greater when lexical items, in particular, lexical heads (e.g., verb), are repeated between prime and target compared to when there is no lexical overlap (Branigan & McLean, 2016; Branigan, Pickering, Stewart, & McLean, 2000; Cleland & Pickering, 2003; Hartsuiker et al., 2008; Pickering & Branigan, 1998; Schoonbaert, Hartsuiker, & Pickering, 2007). This lexical boost effect indicates the presence of a separate mechanism of priming that is lexically driven in nature and that the production system benefits from repeated lexical information. Importantly, however, these lexically specific and independent priming mechanisms differ in their time courses. Abstract priming is overwhelmingly consistent over intervening linguistic materials and time intervals, suggesting that it creates sustaining changes in the system (Bock, Dell, Chang, & Onishi, 2007; Bock & Griffin, 2000; Cleland & Pickering, 2006; Kaschak, 2007). In contrast, at least in the domain of sentence production, the lexical boost effect is generally short lived, dissipating over just a few intervening utterances (Branigan & McLean, 2016; Hartsuiker et al., 2008, and others, but see Pickering, McLean, & Branigan, 2013, for evidence of lasting lexical boost in sentence comprehension).

Researchers have proposed that these effects of structural priming are consequences of language learning (Bock et al., 2007; Chang et al., 2006; Chang, Janciauskas, & Fitz, 2012; Fine & Jaeger, 2013; Reitter, Keller, & Moore, 2011; see Pickering & Ferreira, 2008, for a discussion of other accounts of structural priming). The dual-path model, instantiated by Chang and colleagues, holds that error-based implicit learning in the syntactic sequencing (word order) system underlies abstract priming effects (Chang et al., 2006, 2012; see also Bock & Griffin, 2000). During incremental comprehension of a prime sentence, the individual predicts the next word. When a different word order is encountered (e.g., V NP PP when V NP NP is predicted), this discrepancy (error) is used to adjust connection weights in the system, causing small but persisting changes in future production choices. On the other hand, the lexical boost is attributed to short-term memory–based retrieval in the lexical–semantic system. The repeated lexical item serves as a retrieval cue for the lemma and its link to the associated structural representations in short-term memory, yielding a temporary increase in priming.

In a different model, Reitter et al. (2011) attribute structural priming to activation-based learning in declarative memory. Lasting abstract priming is a result of both base-level learning and spreading activation in the memory system. When a linguistic representation is retrieved from memory, there is spreading activation to related representations. Although the activation decays to some degree over time, repeated retrieval of a structure changes its base-level activation, resulting in persisting facilitation over time. However, a lexical boost effect is purely due to spreading activation from a retrieved lexical item to its related syntax, facilitating their subsequent use only. Although these models differ in terms of specific cognitive constructs that are assumed to underlie the priming effects, they agree that both lexically independent and specific mechanisms of structural priming operate in the normal system (see also Branigan & McLean, 2016). However, it has not yet been clearly examined if this holds true in the aphasic production system.

Structural priming operates not only across linguistic levels but also across different communicative experiences. Nonlinguistic factors, such as communication contexts or the speaker's participation role in conversations, also influence magnitudes of priming (Branigan et al., 2000; Branigan, Pickering, McLean, & Cleland, 2007; Pickering & Garrod, 2004; Reitter & Moore, 2014). Speakers show a particularly strong tendency to align syntactic structures with their interlocutor in a dialogue-like task, the most natural form of communication, compared to a single-speaker priming task. Branigan et al. (2000), for example, used a confederate scripted task where the participant and a confederate partner took turns describing dative action-depicting picture cards with the goal of finding identical pictures. After just hearing their interlocutor's sentences during the “game,” the participants showed 55% and 17.5% priming effects in the same-verb and different-verb prime conditions, respectively. These effects were notably greater than 17.5% and 4.4 % priming effects found in Pickering and Branigan's (1998) single-speaker task, where the participants were presented with booklets of sentence fragments to silently read and complete, including sequences of a same- versus different-verb prime fragment followed by a target fragment designed to elicit a dative structure. This robust priming in dialogue is proposed to support ease of information transfer in a goal-based interactive task by creating shared “routines” or situational models between interlocutors (Pickering & Garrod, 2004; see also Reitter & Moore, 2014) or by reducing the discrepancy between the structures that conversational partners expect to hear and the structures that they actually encounter (T. F. Jaeger & Snider, 2013). The strong priming effects in dialogue also revealed that structural priming does not require speakers to produce the prime structure prior to target production. Instead, comprehension (or listening)–based input is sufficient to modify preferences in message-syntactic associations in the production system, indicating a strong parity in the syntactic processing system between comprehension and production modalities (Bock et al., 2007; Branigan et al., 2000; Chang et al., 2006).

Impaired ability to map a message onto a syntactic structure is pervasive in PWAs, regardless of aphasia types (Caramazza & Berndt, 1985; Caramazza & Miceli, 1991; Lee & Thompson, 2004, 2011a, 2011b; Lee, Yoshida, & Thompson, 2015; Maher et al., 1995; Miceli, Silveri, Romani, & Caramazza, 1989; Saffran, Schwartz, & Marin, 1980a; Thompson, Faroqi-Shah, & Lee, 2015, for review). Sentences requiring rather complex grammatical computations to represent event relationships (e.g., who is doing what to whom) are particularly difficult to comprehend and/or produce for PWAs. Those sentences include, for example, semantically reversible sentences (e.g., the girl is chasing after the boy as opposed to irreversible sentences such as the girl is chasing after the ball), sentences with a noncanonical word order (e.g., passives vs. actives), and sentences involving projection of complex verb argument structures (e.g., datives vs. intransitives; Bastiaanse & Zonneveld, 2005; Cho-Reyes & Thompson, 2012; McAllister, Bachrach, Waters, Michaud, & Caplan, 2009; Saffran et al., 1980a; Saffran, Schwartz, & Marin, 1980b; Thompson, 2003; Thompson, Lange, Schneider, & Shapiro, 1997; Webster, Franklin, & Howard, 2001, 2004, 2007). Consequently, identifying ways to ameliorate the mapping deficits has been an important question in both experimental and intervention studies with PWAs. However, only a few empirically well-tested treatment approaches are available so far. For example, Mapping Therapy and Treatment of Underlying Forms were developed to explicitly teach PWAs to use linguistic rules (e.g., syntactic movement) to “remap” underlying semantic representations onto surface syntactic representations (e.g., Rochon, Laird, Bose, & Scofield, 2005; Schwartz, Saffran, Fink, Meyers, & Martin, 1994; Thompson & Shapiro, 2005; Thompson, Shapiro, Kiran, & Sobecks, 2003).

There is growing evidence that implicit structural priming could also facilitate grammatical encoding processes in aphasia (Cho-Reyes, Mack, & Thompson, 2016; Hartsuiker & Kolk, 1998a; Lee & Man, 2017; Lee, Man, et al., 2019; Rossi, 2015; Saffran & Martin, 1997; Verreyt et al., 2013; Yan, Martin, & Slevc, 2018). Immediately following prime sentences, PWAs show increased production of moderately complex sentences (e.g., passives, datives), although the priming effects are not always statistically reliable (Hartsuiker & Kolk, 1998a; Saffran & Martin, 1997; Yan et al., 2018). For example, in the seminal studies of structural priming in aphasia, Saffran and Martin (1997) found significant priming for transitives but not for datives in a group of participants with mixed aphasia types, whereas Hartsuiker and Kolk (1998a) found significant priming effects for both transitives and datives in participants with agrammatic aphasia. More recent evidence suggests that priming can create enduring effects in PWAs (Cho-Reyes et al., 2016; Lee & Man, 2017; see also Lee, Man, et al., 2019; cf. Schuchard, Nerantzini, & Thompson, 2017). Cho-Reyes et al. (2016) reported persistent abstract priming over as many as four intervening fillers in agrammatic aphasia. Lee and Man (2017) reported an individual with agrammatic aphasia (M. J.), who showed a significantly improved ability to spontaneously produce prepositional object (PO) dative sentences following structural priming training. In addition, the improvement was maintained at 4 weeks posttraining.

Collectively, the emerging evidence from the prior studies suggests that syntactic representations are preserved in PWAs, though they may not be easily accessible for PWAs during sentence production (Kolk, 1995; Kolk & Heeschen, 1992; Kolk & Van Grunsven, 1985; Lee et al., 2015; Linebarger, Schwartz, Romania, Kohn, & Stephens, 2000; Linebarger, Schwartz, & Saffran, 1983). Structural priming could facilitate activation and selection of target syntactic structures in PWAs, suggesting that it could be used as an intervention technique for remediating grammatical encoding deficits in aphasia. However, as yet, it remains largely unknown what linguistic and nonlinguistic factors modulate strength and longevity of structural priming in aphasia. Without this knowledge established, effective use of structural priming as a remediation strategy for PWAs would be limited.

We do not know, for example, whether a dialogue-like comprehension-to-production task effectively generates positive and enduring priming in PWAs, as shown in unimpaired speakers. Most previous studies in aphasia used a single-speaker experimental task where the participant would orally repeat or read a prime sentence prior to target production (Cho-Reyes et al., 2016; Hartsuiker & Kolk, 1998a; Lee & Man, 2017; Saffran & Martin, 1997; Yan et al., 2018; but see Rossi, 2015; Verreyt et al., 2013, for nonproduction tasks). In a recent study, Lee, Hosokawa, Meehan, Martin, and Branigan (2019) found that PWAs could reuse their interlocutor's syntactic structures in their own production in a collaborative picture-matching game involving a blocked priming design. Interestingly, the priming effect was found when the PWAs orally repeated the prime sentences they heard (interlocutor's picture descriptions) during the picture matching (prime) block prior to the production block, but not when the primes were processed in listening only, that is in a comprehension-to-production task. However, the use of a blocked priming design in Lee et al.'s study naturally created a lag of approximately 10–12 intervening utterances between the prime and the target (see Lee, Hosokawa, et al., 2019, for details). The participants first processed a block of 12 different prime sentences (a mix of four transitive, four dative, and four locative alternations) prior to their turn to produce 12 target sentences (production block). This lag is substantially greater than zero to two lags used in most dialogue-based priming studies in young adults and children (e.g., Branigan & McLean, 2016; Peter, Chang, Pine, Blything, & Rowland, 2015; Rowland, Chang, Ambridge, Pine, & Lieven, 2012). Thus, it remains unclear whether the null results from Lee et al.'s comprehension-to-production task were due to the experimental design or if prior linguistic experiences based solely on comprehension are insufficient to modify message–structure mappings in the production system of PWAs. A dialogue task involving a shorter lag would allow us to tease this apart.

We also do not know if and to what extent short-term and longer term priming effects are modulated by lexically specific and independent primes in aphasia. There is only one study by Yan et al. (2018), who has examined and found a lexical boost effect during sentence production in PWAs. Their PWAs demonstrated a significantly greater priming effect on production of transitive sentences when the verb was repeated between prime and target. In addition, the magnitudes of lexical boost effects (as well as abstract priming effects) were comparable between PWAs and healthy older adults (HOAs). However, the study examined only sentences with transitive (active/passive) alternations, and the target sentence was elicited immediately following the prime. In addition, they used a single-speaker priming task where the participant orally repeated an auditorily presented prime sentence and then read a written version of the prime to verify if their repetition was correct. This two-step priming might have encouraged the participant to better encode and reuse the lexical–semantic materials of the prime. Different from Yan et al.'s findings, we (Lee, Hosokawa, et al., 2019) failed to find a lexical boost effect during comprehension of syntactically ambiguous sentences. However, the PWAs still demonstrated abstract priming not only in the immediate priming condition (0-lag) but also over two intervening utterances (2-lag). Therefore, further investigation is needed to better understand if the lexical boost and/or abstract structural priming are truly preserved and persistent mechanisms in aphasia.

The purpose of this study was, therefore, to systematically investigate a set of important questions on structural priming in aphasia, with the long-term goal of delineating factors associated with robust and/or long-lasting priming effects in aphasia. We first asked whether PWAs demonstrate significant structural priming in a dialogue-like comprehension-to-production task. We used a collaborative picture-matching task in both experiments, where the participant took turns describing pictures with an experimenter with the goal of finding identical (“Bingo”) picture cards. It was predicted that PWAs would show significant priming in our task, if comprehension-based priming is sufficient to change their structural preferences during sentence production.

If PWAs showed priming in dialogue, our second question was to examine whether both lexical boost and abstract priming are preserved in PWAs, as found in Yan et al. (2018), or whether they demonstrate only abstract priming, as found in Lee, Hosokawa, et al. (2019). Thus, Experiment 1 examined the effects of same- versus different-verb primes on the production of transitive and dative alternations when the target sentence was elicited immediately after the prime, that is, immediate priming (0-lag). Importantly, we included not only transitive but also dative target sentences, thereby allowing us to further examine the generalizability of the priming effects across different structures. PWAs were expected to demonstrate abstract priming effects in immediate priming, consistent with previous structural priming studies in production (Cho-Reyes et al., 2016; Hartsuiker & Kolk, 1998a; Saffran & Martin, 1997) and comprehension (Lee, Hosokawa, et al., 2019). If lexically specific immediate priming is also preserved in aphasia, PWAs were predicted to show a significantly greater priming effect in the same-verb prime condition than in the different-verb prime condition (Yan et al., 2018). Finally, we examined the time courses of abstract priming and lexical boost effects to elucidate learning of grammatical encoding in aphasia. To address this question, Experiment 2 replicated Experiment 1 with one modification: Two filler trials interceded between prime and target, thereby allowing examination of lasting priming effects. Following Lee, Hosokawa, et al., it was predicted that our PWAs might show persistent abstract priming but no lexical boost over intervening fillers.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 used a dialogue-like picture-matching game to examine if comprehension-to-production priming is preserved in aphasia when the target was elicited immediately following the prime. Participants took turns with the experimenter describing picture cards with the goal of finding matching (Bingo) pictures. To test if HOAs and PWAs show a lexical boost effect, half of the prime–target pairs contained the same verb, whereas the other half contained different verbs.

Method

Participants

Seventeen PWAs (four women, 13 men; M age = 63.1 years, range: 52–80 years; education mean = 14.5 years, range: 10–20 years) were included in this study. In addition, 20 HOAs (13 women, seven men; M age = 70.7 years, range: 60–82 years; education mean = 16.5 years, range: 12–23 years) were recruited as control participants. All participants were monolingual native speakers of English and reported no history of neurological or psychological disorders prior to stroke or study participation that could affect communication. All reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision and passed a hearing screening at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz at 40 dB in at least one ear. HOAs' cognitive–linguistic abilities were screened using the Cognitive Linguistic Quick Test (Helm-Estabrooks, 2001). All HOAs scored within normal limits for their age, indicating that there were no significant age-related changes in their attention, memory, executive function, language, and visuospatial skills (composite severity rating mean = 3.98, SD = 0.06, normal range: 3.5–4.0). Participants were compensated for their time and provided informed consent prior to the study. All HOAs were tested at Purdue University, whereas PWAs were tested at Purdue University and Temple University. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of these universities.

PWAs had a diagnosis of aphasia following a left cerebrovascular accident at least 6 months prior to the study, except for one PWA who suffered a stroke 2 months prior (M = 75 months, SD = 46). A battery of cognitive–linguistic tests was administered with PWAs, as shown in Table 1. Given the nature of the current experimental task, participants with mild–moderate fluent or nonfluent aphasia, as demonstrated by an Aphasia Quotient of greater than 60 on the Western Aphasia Battery–Revised (WAB-R Aphasia Quotient range: 66.8–97.4; Kertesz, 2006), were included. All participants demonstrated preserved ability to comprehend single words and simple sentences, as indicated by an average score of 5/10 in the Auditory Comprehension section of the WAB-R, 80% on the Verb Comprehension Test, and above chance level on the comprehension of canonical sentences of the Sentence Comprehension Test of the Northwestern Assessment of Verbs and Sentences (NAVS; Thompson, 2012). In order to ensure that the participants have preserved ability to produce at least some canonical sentences, we included those who scored at least 4/10 on the Fluency section of the WAB-R, minimum 50% correct on the Verb Naming Test and the Argument Structure Production Test of the NAVS. On the Sentence Production Priming subtest of the NAVS, as a group, PWAs produced canonical sentences more correctly than noncanonical sentences (72% vs. 47%), consistent with marked difficulty with syntactically complex sentences in both fluent and nonfluent aphasia (Cho-Reyes & Thompson, 2012).

Table 1.

Language testing results for persons with aphasia (PWAs).

| PWA | WAB-R |

NAVS |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQ (100) |

Fluency (10) |

AC (10) |

VNT (100) |

VCT (100) |

ASPT (100) |

SPPT_C (100) |

SPPT_NC (100) |

SCT_C (100) |

SCT_NC (100) |

|

| A1 | 92.9 | 9 | 9.4 | 91 | 100 | 97 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| A2 | 75.7 | 4 | 8.5 | 86 | 100 | 94 | 73 | 33 | 87 | 93 |

| A3 | 78.6 | 6 | 9.0 | 96 | 100 | 88 | 60 | 7 | 93 | 100 |

| A4 | 84.6 | 6 | 9.1 | 100 | 100 | 97 | 93 | 80 | 100 | 93 |

| A5 | 70.3 | 8 | 5.3 | 80 | 100 | 69 | 13 | 0 | 60 | 33 |

| A6 | 82.9 | 6 | 8.9 | 86 | 100 | 91 | 47 | 20 | 47 | 60 |

| A7 | 91.6 | 9 | 8.7 | 73 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 33 | 87 | 100 |

| A8 | 77.0 | 6 | 8.8 | 50 | 100 | 94 | 80 | 7 | 80 | 60 |

| A9 | 75.0 | 8 | 6.7 | 77 | 86 | 66 | 20 | 27 | 73 | 47 |

| A10 | 97.4 | 9 | 10.0 | 96 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| A11 | 83.0 | 5 | 10.0 | 97 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 93 | 100 | 100 |

| A12 | 69.6 | 5 | 8.7 | 73 | 100 | 100 | 13 | 0 | 93 | 27 |

| A13 | 93.1 | 9 | 9.9 | 95 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| A14 | 89.2 | 8 | 9.6 | 95 | 100 | 100 | 87 | 93 | 100 | 93 |

| A15 | 74.3 | 4 | 8.4 | 79 | 82 | 53 | 60 | 40 | 60 | 60 |

| A16 | 66.8 | 4 | 8.3 | 55 | 100 | 91 | 93 | 60 | 53 | 27 |

| A17 | 83.0 | 6 | 8.8 | 64 | 100 | 94 | 80 | 13 | 100 | 80 |

| M | 81.5 | 6.6 | 8.7 | 82 | 98 | 90 | 72 | 47 | 84 | 75 |

| SD | 9.1 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 15 | 5 | 14 | 31 | 39 | 19 | 28 |

Note. WAB-R = Western Aphasia Battery–Revised; NAVS = Northwestern Assessment of Verbs and Sentences; AQ = Aphasia Quotient; AC = Auditory Comprehension; VNT = Verb Naming Test; VCT = Verb Comprehension Test; ASPT = Argument Structure Production Test; SPPT_C = Sentence Production Priming Test (Canonical); SPPT_NC = Sentence Production Priming Test (Noncanonical); SCT_C = Sentence Comprehension Test (Canonical); SCT_NC = Sentence Comprehension Test (Noncanonical).

In addition, participants' lexical–semantic short-term memory was measured using two subtests of the Temple Assessment of Language and Short-Term Memory in Aphasia (TALSA; Martin, Kohen, & Kalinyak-Fliszar, 2010) as shown in Table 2: Category Probe Span and Synonym Triplet Three-Word and Two-Word. These tests assess one's ability to hold a set of words in short-term memory while judging semantic category membership of a target word or selecting a semantically related word to a target word (see Martin, Kohen, Kalinyak-Fliszar, Soveri, & Laine, 2012; Martin, Minkina, Kohen, & Kalinyak-Flizsar, 2018, for detailed descriptions of the tests). Three of 17 PWAs could not complete the TALSA due to time constraints. PWAs performed significantly worse than HOAs on all three subtests, ts(30) < 2.3, ps < .05. This pattern is consistent with previous findings that lexical–semantic short-term memory impairments are common in aphasia (Allen, Martin, & Martin, 2012; Barde, Schwartz, Chrysikou, & Thompson-Schill, 2010; Martin & Ayala, 2004; Pettigrew & Martin, 2016).

Table 2.

Persons with aphasia's (PWA) performance on selected lexical–semantic short-term memory subtests of the Temple Assessment of Language and Short-Term Memory in Aphasia (TALSA).

| Participant | TALSA |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category Probe (7) |

Synonym Triplet 3-Item (40) |

Synonym Triplet 2-Item (40) |

|

| A1 | 3.8 | 37 | 40 |

| A2 | 1.8 | 32 | 36 |

| A3 | 1.8 | 30 | 29 |

| A4 | 4.6 | 38 | 39 |

| A5 | 0.0 | 27 | 32 |

| A6 | 2.7 | 29 | 39 |

| A7 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| A8 | 4.0 | 32 | 40 |

| A9 | 1.2 | 27 | 32 |

| A10 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| A11 | 4.3 | 39 | 38 |

| A12 | 2.6 | 38 | 35 |

| A13 | 2.3 | 39 | 40 |

| A14 | 3.9 | 39 | 39 |

| A15 | 1.9 | n/a | n/a |

| A16 | 3.4 | 32 | 37 |

| A17 | 2.5 | 27 | 32 |

| PWA, M (SD) | 2.7 (1.3) | 33 (5) | 36 (4) |

| HOA, M (SD) | 6.3 (1.0) | 39 (1) | 40 (0.2) |

Note. The group means (SDs) are provided for healthy older adults (HOAs). n/a = unable to complete.

Materials and Design

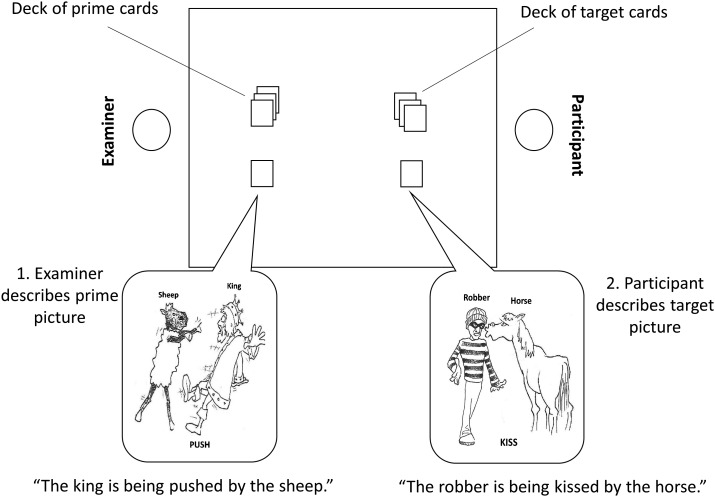

For transitive stimuli, a set of 48 target and 48 prime sentences and their corresponding black-and-white line drawings were taken from Branigan and McLean (2016). The pictures depicted an animal agent and human theme in one of the six actions (bite, chase, kiss, lift, pull, push; see Figure 1 for an example stimulus). Each verb was used eight times in the prime pictures and eight times in the target pictures with different agent–theme pairs. For dative stimuli, another set of 96 (48 target and 48 prime) sentences and associated pictures were taken from Branigan's stimuli bank. These stimuli effectively elicited priming effects in young adults in previous studies (e.g., Branigan, Pickering, & Cleland, 2000). The dative pictures depicted a human agent and goal and an inanimate theme in one of the six actions (give, hand, offer, sell, show, and throw). Each verb was used in eight prime pictures and in eight target pictures. The target verb and nouns were written on the picture card in order to minimize confounding effects on sentence production from word retrieval difficulties of PWAs (see Figure 1). The picture stimuli were printed as 4 1/2 in. × 3 2/3 in. cards on card stock paper.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup, demonstrating a transitive prime–target pair in Experiment 1 (0-lag). Two filler trials intervened between prime and target in Experiment 2 (2-lag).

Each transitive target picture was paired once with an active prime and once with a passive prime. Likewise, each dative picture was paired once with a PO prime and once with a double-object (DO) prime. In addition, within the target structure, half of the prime–target pairs had the same verb, and the other half had different verbs. Therefore, each target picture was elicited four times across four different prime conditions, as demonstrated in Table 3. Prime and target items were paired carefully so that there was no overlap in the phonological and semantic content of the nouns used between prime and target. In addition, 192 intransitive sentences and corresponding pictures were prepared for fillers. Of these 192 fillers, 31 were used as the Bingo items. The Bingo items involved identical picture cards between the experimenter and the participant's card stacks and were included to ensure that the participants actively attended to the task.

Table 3.

A set of example target and prime stimuli used in both experiments.

| Target structure | Example stimuli | Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Transitive | A horse pulling a girl The tiger is pulling the soldier. The soldier is being pulled by the tiger. The dog is chasing the queen. The queen is being chased by the dog. |

Target transitive picture Same verb, active prime Same verb, passive prime Different verb, active prime Different verb, passive prime |

| Dative | A nun throwing a mug to a swimmer The chef is throwing the gun to the boxer. The chef is throwing the boxer the gun. The thief is giving the hat to the priest. The thief is giving the priest the hat. |

Target dative picture Same verb, PO prime Same verb, DO prime Different verb, PO prime Different verb, DO prime |

Note. Each target picture can be described in alternating syntactic structures (active/passive for transitive; PO/DO for dative). PO = prepositional object; DO = double object.

Four lists were created for the experiment. Each list consisted of a total of 96 experimental trials, including 48 transitive prime–target pairs and 48 dative prime–target pairs, and 192 filler trials. Each target picture was presented only once within the list, paired with one of the four different primes across the four lists. For example, the target transitive picture the tiger is biting the fireman was paired with the same verb-active prime the rabbit is biting the doctor in List 1, but with a same-verb, passive prime the doctor is being bitten by the rabbit in List 2, and so on. The order in which experimental trials were presented within each list was pseudorandomized, such that no same-prime condition (transitive or dative primes) was presented in two consecutive trials. In addition, two filler trials were presented after each experimental trial. Each participant received only one list. The order of the list was counterbalanced across the participants.

Procedure

Prior to the experimental task, all participants were familiarized with the target and filler nouns and verbs as singletons using a stimulus book. This was done to minimize the influence of aphasic participants' word retrieval difficulties on the sentence production task. For nouns, the participants were shown a stimuli book, including a set of black-and-white drawings of the characters and objects with their names written (e.g., “rabbit”) underneath, and were asked to name them. For verbs, participants were asked to read written verbs (“bite”) without any associated drawings. Feedback was provided for any errors produced.

For the experimental task, the experimenter and participant played a picture–card matching game, with the goal being to find the matching (Bingo) pictures, as demonstrated in Figure 1. The experimenter and the participant each had a stack of cards in front of them face down on the table. The experimenter's stack contained the prime and filler cards, and the participant's stack contained the target and filler cards. The participants were told that they would be playing a card game called Bingo, where they would take turns turning over their top card and describing each picture with a single complete sentence using all the words on the card. When the experimenter and the participant had cards that were identical, the participant was required to say “Bingo!” The experimenter always described their picture first and produced different types of prime sentences following a color cue marked on the bottom right corner of the prime picture card (pink = PO, blue = DO, green = active, orange = passive). There was no color cue on the participant's picture cards, such that the participant was unaware of the prime manipulation. A set of four practice trials preceded the game. The participants' responses were audio-recorded for data analysis.

Data Coding and Analyses

Participants' responses were transcribed verbatim, and each response was coded as a “correct” or “incorrect” target response. A response was considered as “correct” if it included all the target nouns and the verb in one of the alternating target structures (active or passive for transitives; PO or DO for datives). When multiple attempts were made, the final sentential response was scored. When a subject noun phrase and a verb predicate were produced minimally (e.g., the man was chased), the response was considered as a sentential response. Production of synonyms (e.g., boy for man), intelligible phonological paraphasias, omission of articles, and disfluencies (e.g., fillers, self-corrected responses) were accepted. For actives, the response had to be in the NP (agent) V NP (theme) constituent order to be considered “correct,” with variances in verb tense forms (lifted, is lifting, lifts) permitted. A correct passive response had to contain the theme in the preverbal position, the agent in the postverbal position preceded by the preposition “by.” With regard to the verbal morphology of passive responses produced by PWAs, we accepted omission of an auxiliary verb (the doctor lifted by the lion) or production of non–past participle form of the verb (e.g., pushing, push for pushed), following prior studies using “lenient” scoring with PWAs (Hartsuiker & Kolk, 1998a, Saffran & Martin, 1997; see also Branigan & McLean, 2016, with children). 1 For HOAs, only responses with correct passive verbal morphology (auxiliary + past participle) were considered as “correct.” For a PO structure, production of semantically legitimate prepositions in the prepositional phrase that can be used with an animate noun (for, to, with) were accepted but not the prepositions that are more generally used with an inanimate noun (in, on). Phonological paraphasias were accepted if 50% or more phonemes of a target word were intelligible.

The following responses were considered as “incorrect” responses: role reversal errors in which thematic roles were reversed in the target structure (e.g., lion is being lifted by doctor for the doctor is being lifted by the lion), verb argument structure errors including omitted or incorrectly produced arguments (e.g., pushed by a cat for the fireman is being pushed by a cat; a priest is handing a pitcher a boxer for a priest is handing a pitcher to the boxer), and off-target verb and noun substitutions (e.g., feeding for handing; chef for artist). Nonsentence responses (e.g., professor is apple…apple a doctor) and sentence responses with a nontarget structure (e.g., the soldier is being handed a pitcher by a ballerina for the PO target the ballerina is handing a pitcher to the soldier) were also excluded, as well as unintelligible or “I don't know” responses.

The analysis of priming effects was conducted based on “correct” target responses only. The priming effect was defined as the increased production of an arbitrarily selected structural alternative (i.e., active for transitive targets; PO for dative targets in this study) following the same versus the alternative prime structures. In other words, the priming effect for transitives was the increased proportion of active sentences produced following an active prime versus following a passive prime. The proportion of active responses in each prime condition was calculated for each participant by dividing the number of active responses in that condition by the total number of active plus passive responses in that condition. Similarly, the priming effect for dative targets was the increased proportion of PO sentences produced following a PO prime versus following a DO prime. The proportion of PO responses in each prime condition was calculated for each participant by dividing the number of PO responses in that condition by the total number of PO and DO responses in that condition.

Statistical Analysis

To compare group differences on production of “correct” responses, we used a 2 (group) × 2 (prime type) × 2 (verb type) mixed analysis of variance within each target structure. Statistical analyses of priming effects were conducted using mixed-effects logistic regression to compare probability of a specific response (an active response for transitives; a PO response for datives) in the different prime conditions (lme4 package; Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, 2014; F. T. Jaeger, 2008). A series of models were used for each target structure. Data were first modeled including both groups in order to compare priming effects between the groups. These models included prime, verb, group, and their two- and three-way interactions as fixed factors. Second, a separate model was used for each participant group in order to test for priming effects across conditions. In these models, prime, verb, and their interactions were entered as fixed factors. For all the models, the random effects structure included by-participant and by-item intercepts as well as by-participant and by-items slopes for all main effects. In addition, whenever relevant, we calculated effect sizes of the priming effects (Cohen's d) for each condition within participant group to directly compare magnitudes of priming between the groups while factoring out differences in variability (Cohen, 1992; Dunlap, Cortina, Vaslow, & Burke, 1996).

Results and Summary

For HOAs, we excluded 15 responses from a total of 1,920 responses due to experimental errors, resulting in a total of 1,905 scorable responses. For PWAs, eight responses were excluded from a total of 1,632 due to experimental errors, resulting in a total of 1,624 scorable responses.

Accuracy Analysis

Table 4 summarizes proportions of accurate target responses produced for each participant group for different prime conditions. For transitive targets, only the group effect was significant, indicating that PWAs produced significantly fewer accurate target responses in general (PWA: 77% vs. HOA: 99%), F(1, 35) = 16.34, p < .001. The main effects of verb and prime and any of the two- and three-way interactions were not reliable (Fs < 0.97). Similarly, for dative targets, PWAs produced fewer accurate responses compared to HOAs in general (PWA: 87% vs. HOA: 99%), F(1, 35) = 8.79, p = .005. No other main effects or two-way interactions were significant (Fs < 2.45). The three-way interaction was significant, F(1, 35) = 13.22, p = .001, indicating a larger group difference in accuracy for same-verb trials in the PO prime condition, but a larger group difference in accuracy for different-verb trials in the DO prime condition. However, this interaction has no theoretical bearing; thus, we do not discuss it further.

Table 4.

Proportions of “correct” target responses produced under each prime condition for Experiments 1 and 2.

| Verb | Prime | Experiment 1 |

Experiment 2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOA | PWA | HOA | PWA | ||

| Transitive targets | |||||

| Same verb | Active | 100% | 77% | 100% | 80% |

| Passive | 100% | 75% | 100% | 79% | |

| Different verb | Active | 99% | 77% | 100% | 82% |

| Passive | 100% | 77% | 100% | 80% | |

| Dative targets | |||||

| Same verb | PO | 100% | 85% | 99% | 88% |

| DO | 99% | 90% | 99% | 86% | |

| Different verb | PO | 98% | 88% | 99% | 87% |

| DO | 100% | 88% | 99% | 86% | |

Note. HOA = healthy older adult; PWA = person with aphasia; PO = prepositional object; DO = double object.

Error types were tallied. For transitive targets, the most common errors produced by PWAs were role reversal errors (61%; e.g., the boy is biting the rabbit for the rabbit is biting the boy) followed by noun substitution errors (8%; e.g., bear pulling a boy for the bear is pulling the girl). For dative targets, PWAs produced incorrect argument structure errors (41%; e.g., cowboy…offers…banana…thief for the cowboy is offering the banana to the thief) and noun substitution errors (16%; e.g., The ballerina…hands…the pitcher to the sailor for the ballerina is handing the pitcher to the soldier) most frequently.

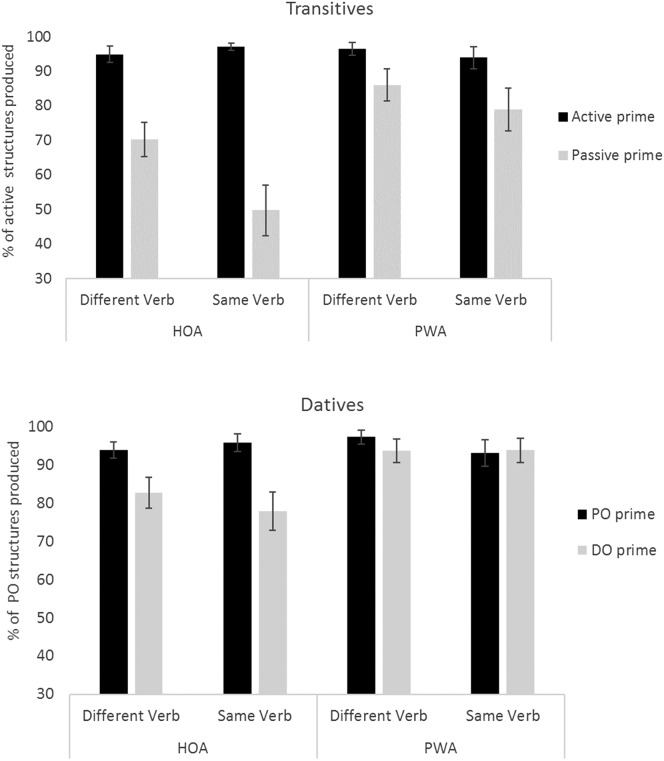

Priming Analysis 2

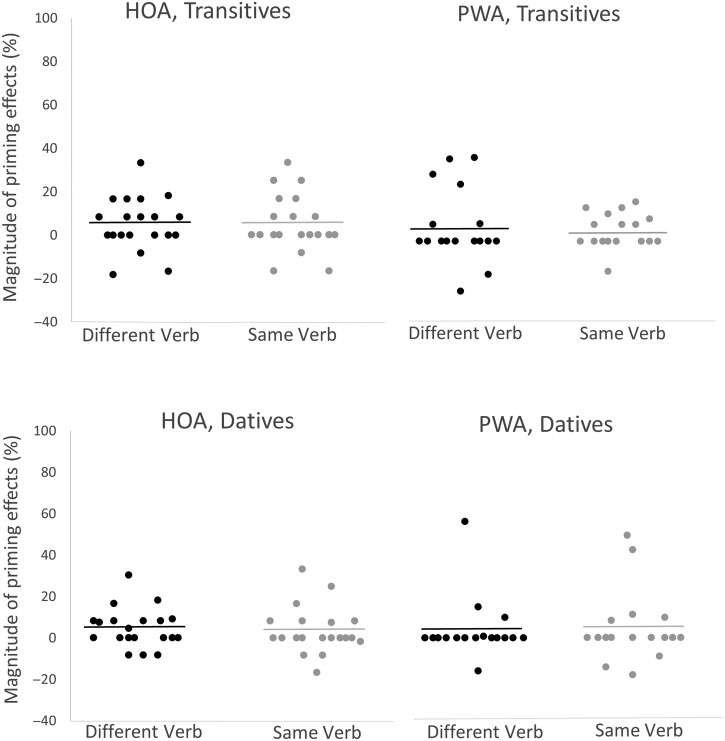

Figure 2 shows priming effects for transitive and dative targets in each group for Experiment 1. Figure 3 shows individual participants' magnitudes of priming effects for both PWAs and HOAs. The results of the mixed-effects models are summarized in Table 5. We first discuss the results from a mixed-effects model comparing the groups, followed by the results of a mixed-effects model for each participant group individually. For the transitive targets, the model comparing the group effects revealed a significant effect of prime type, indicating that participants were more likely to produce active structures following active than following passive primes. A significant effect of verb type indicated more active responses in the same-verb than in the different-verb prime condition. A main effect of group indicated greater production of active structures in PWAs than in HOAs. These two main effects provide no theoretical challenges. Among two-way interactions, only the Prime × Verb interaction was significant, indicating increased priming for the same- versus different-verb primes. Importantly, the three-way (Prime × Verb × Group) interaction was significant at α = .05, indicating the lexical boost may be significant only in one group.

Figure 2.

Priming results (with standard error bars) for transitive (top) and dative (bottom) targets for healthy older adults (HOAs) and persons with aphasia (PWAs) in Experiment 1 (0-lag). For transitive targets, increased percentage of active structures produced following active versus passive primes indicates the priming effect. For dative targets, increased percentage of prepositional object (PO) structures produced following PO versus double-object (DO) primes indicates the priming effect.

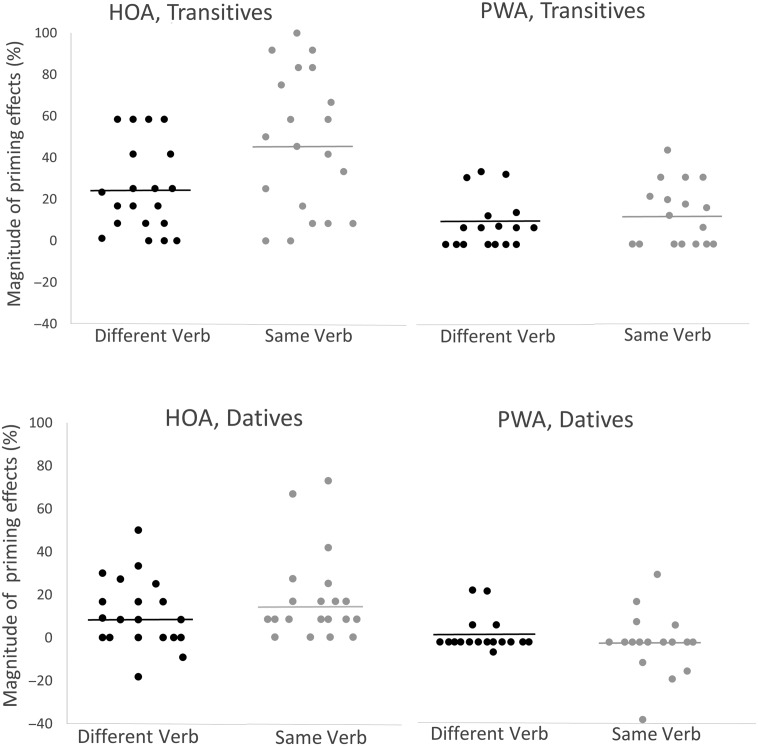

Figure 3.

Magnitudes of priming in individual persons with aphasia (PWAs) and healthy older adults (HOAs) for Experiment 1. For transitive targets, magnitude of priming corresponds to the difference in proportions of active structures produced between active and passive prime conditions. For dative targets, magnitude of priming corresponds to the difference in proportions of prepositional object structures produced between prepositional object and double-object prime conditions.

Table 5.

Summary of logistic mixed-effects models, Experiment 1.

| Predictors | Log odds estimate | SE | z | Pr (> |z|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transitive: HOA vs. PWA | ||||

| (Intercept) | 1.10 | 0.35 | ||

| Prime Type | 2.25 | 0.47 | 4.75 | < .0001 |

| Verb | −1.11 | 0.24 | −4.59 | < .0001 |

| Group | 1.48 | 0.66 | 2.24 | < .05 |

| Prime Type × Verb | 1.62 | 0.55 | 2.95 | < .01 |

| Prime Type × Group | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.89 | .37 |

| Verb × Group | 0.26 | 0.45 | 0.58 | .56 |

| Prime Type × Verb × Group | −1.73 | 0.89 | −1.93 | .05 |

| Transitive: HOA | ||||

| (Intercept) | 1.11 | 0.37 | ||

| Prime Type | 2.19 | 0.48 | 4.55 | < .0001 |

| Verb | −1.13 | 0.26 | −4.34 | < .0001 |

| Prime Type × Verb | 1.56 | 0.55 | 2.85 | < .01 |

| Transitive: PWA | ||||

| (Intercept) | 2.42 | 0.49 | ||

| Prime Type | 2.59 | 0.64 | 4.07 | < .001 |

| Verb | −0.63 | 0.38 | −1.68 | .09 |

| Prime Type × Verb | 0.13 | 0.71 | 0.18 | .86 |

| Dative: HOA vs. PWA | ||||

| (Intercept) | 4 | 0.33 | ||

| Prime Type | 1.57 | 0.45 | 3.48 | < .001 |

| Verb | −0.32 | 0.28 | −1.14 | .25 |

| Group | 2.00 | 0.75 | 2.67 | < .01 |

| Prime Type × Verb | 0.91 | 0.53 | 1.72 | .08 |

| Prime Type × Group | −0.45 | 0.90 | −0.49 | .62 |

| Verb × Group | −0.06 | 0.60 | −0.10 | .92 |

| Prime Type × Verb × Group | −1.97 | 1.00 | −1.97 | .05 |

| Dative: HOA | ||||

| (Intercept) | 1.85 | 0.32 | ||

| Prime Type | 1.54 | 0.44 | 3.53 | < .001 |

| Verb | −0.32 | 0.27 | −1.20 | .23 |

| Prime Type × Verb | 0.89 | 0.53 | 1.69 | .09 |

| Dative: PWA | ||||

| (Intercept) | 4.68 | 1.01 | ||

| Prime Type | 1.39 | 1.05 | 1.33 | .18 |

| Verb | −1.30 | 0.77 | −1.68 | .09 |

| Prime Type × Verb | −1.14 | 0.97 | −1.18 | .24 |

Note. HOAs = healthy older adults; PWA = persons with aphasia.

The mixed-effects model for HOAs revealed significant main effects of prime type and verb type. Importantly, the interaction between prime type and verb type was significant, indicating a significantly greater priming effect in the same-verb condition compared to the different-verb condition. HOAs produced on average 47% more active responses following active compared to passive primes in the same-verb condition (d = 2.02). When different verbs were used between prime and target, HOAs produced on average 25% more active responses following active compared to passive primes (d =1.40). For PWAs, however, only the effect of prime type was significant. They showed numerically greater priming following the same-verb primes (mean 15% difference, d = 0.74) compared to the different-verb primes (mean 10% difference, d = 0.72), but this difference was not significant. Although there was substantial individual variability in magnitude of priming (see Figure 3), PWAs, in general, showed relatively similar priming effects between the same- and different-verb conditions. HOAs also showed substantial variability in magnitude of priming overall but demonstrated greater priming effects for the same-verb versus different-verb condition.

For the dative targets, the mixed-effects model comparing groups revealed a significant effect of prime type, indicating overall increased PO responses following PO versus DO primes. Overall, there was increased production of PO responses in PWAs compared to HOAs, as indicated by a significant group effect. The main effect of verb type was not significant. There was a significant Prime × Group interaction, indicating greater priming effects in HOAs than in PWAs. No other two-way interaction was significant. Lastly, there was a significant Prime Type × Verb × Group interaction.

The results of a mixed-effects model for HOAs revealed a significant effect of prime type only, but no effect of verb type. The interaction between prime type and verb type did not reach significance, although HOAs showed a larger effect size in priming when the same-verb condition (mean 18% difference, d = 1.03) compared to the different-verb condition (mean 11% difference, d = 0.76). On the other hand, PWAs failed to show any significant effect of prime type, verb type, or interaction between the two in datives. PWAs showed a negative priming effect in the same-verb condition (mean −0.67% difference, d = 0.00) and a small priming effect in the different-verb condition (mean 4% difference, d = 0.35; see Figure 3 for HOA and PWA individual data).

To summarize the results from Experiment 1, PWAs showed clearly different patterns of results from HOAs. For HOAs, both abstract priming and lexical boost were significant in transitive targets, and only abstract priming was significant for dative targets. However, PWAs demonstrated only abstract priming in transitive targets and no priming in dative targets.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 examined whether PWAs and HOAs demonstrate persisting priming effects over intervening utterances. Thus, two intransitive filler items were embedded between the prime and the target. The rest of the experiment remained the same as in Experiment 1.

Method

Participants

The same 17 PWAs and 20 HOAs who participated in Experiment 1 participated in Experiment 2 with a minimum of 2 weeks between experiments. The order in which the participants completed the two experiments was counterbalanced.

Materials, Procedure, and Data Analyses

The same experimental materials, procedures, and data analyses were followed from Experiment 1 with one modification: Each prime–target pair included two intervening filler items. That is, during the picture-matching game, each trial consisted of a prime picture described by the experimenter, a filler picture described by the participant, a filler picture described by the experimenter, and a target picture described by the participant.

Results and Summary

For HOAs, eight responses were excluded from a total of 1,920 responses due to experimental errors, resulting in 1,912 scorable responses. For PWAs, 12 responses were excluded from a total of 1,632 responses due to experimental errors, resulting in 1,624 scorable responses.

Accuracy Analysis

Table 4 shows proportions of accurate target responses for Experiment 2. For transitive targets, only the group effect was significant, indicating that PWAs produced significantly fewer accurate target responses overall (PWA: 80% vs. HOA: 99%), F(1, 35) = 1447.600, p < .001. The main effects of verb and prime and any of the two- and three-way interactions were not significant (Fs < 0.63). Similarly, for dative targets, PWAs produced fewer accurate responses compared to HOAs overall (PWA: 87% vs. HOA: 99%), F(1, 35) = 2170.98, p < .001. No other effects were significant (Fs < 2.56). Error analysis revealed that PWAs produced role reversal errors (65%) and “other” type errors (12%) most frequently for transitive targets. They produced incorrect argument structure errors (43%) and noun substitution errors (18%) most frequently for dative targets, similar to Experiment 1.

Priming Analysis

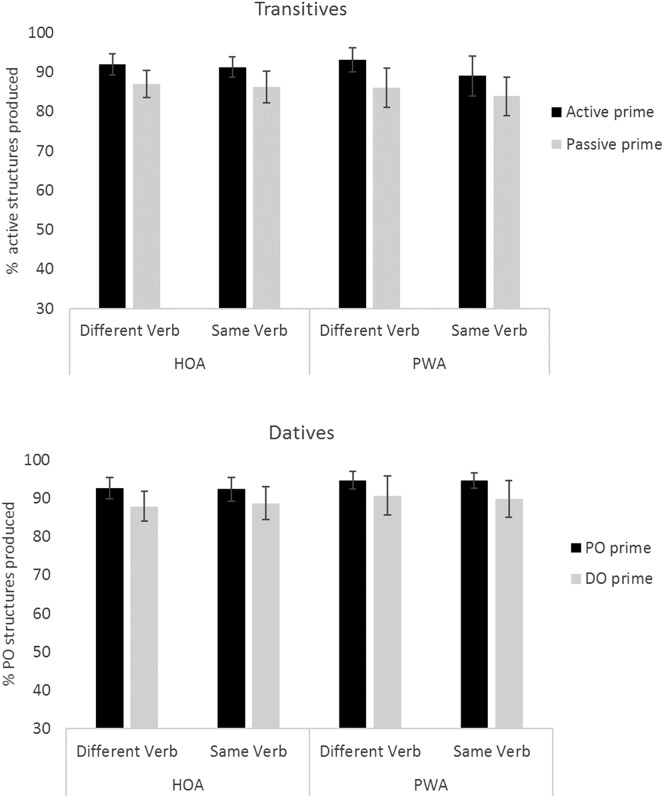

The priming effects for HOAs and PWAs across different priming conditions are presented for each target structure in Figure 4. Figure 5 shows individual participants' magnitudes of priming effects. The results of the mixed-effects models are presented in Table 6. For transitive targets, the model comparing groups revealed that there was only a significant effect of prime type, indicating that more active responses were produced overall after active rather than after passive primes. No other main effects or two- and three-way interactions were significant, indicating that the priming effect did not vary as an effect of participant group or verb type. In the mixed-effects model of HOAs, only prime type was significant. HOAs showed a small but significant priming effect regardless of verb overlap, that is, no lexical boost (5% difference for same-verb primes, d = 0.33; 5% difference for different-verb primes, d = 0.36). Similarly, PWAs demonstrated a significant effect of prime type, but no effects of verb type or interaction between the two. They showed comparable priming effects between the same-verb (mean 5% difference, d = 0.25) and different-verb (mean 7% difference, d = 0.41) conditions, with individual variability being greater in the different- versus same-verb condition (see Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Priming results (with standard errors) for transitive (top) and dative (bottom) targets for healthy older adults (HOAs) and persons with aphasia (PWAs) in Experiment 2 (2-lag). For transitive targets, increased percentage of active structures produced following active versus passive primes indicates the priming effect. For dative targets, increased percentage of prepositional object (PO) structures produced following PO versus double-object (DO) primes indicates the priming effect.

Figure 5.

Magnitudes of priming in individual persons with aphasia (PWAs) and healthy older adults (HOAs) for Experiment 2. For transitive targets, magnitude of priming corresponds to the difference in proportions of active structures produced between active and passive prime conditions. For dative targets, magnitude of priming corresponds to the difference in proportions of prepositional object structures produced between prepositional object and double-object prime conditions.

Table 6.

Summary of logistic mixed effects models, Experiment 2.

| Predictors | Log odds estimate | SE | z | Pr (> |z|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transitive: HOA vs. PWA | ||||

| (Intercept) | 2.46 | 0.42 | ||

| Prime Type | 1.13 | 0.47 | 2.42 | < .05 |

| Verb | −0.12 | 0.34 | −0.35 | .72 |

| Group | 0.10 | 0.73 | 0.14 | .89 |

| Prime Type × Verb | 0.04 | 0.49 | 0.09 | .93 |

| Prime Type × Group | 0.55 | 0.71 | 0.78 | .43 |

| Verb × Group | 0.09 | 0.53 | 0.16 | .87 |

| Prime Type × Verb × Group | −0.26 | 0.77 | −0.34 | .74 |

| Transitive: HOA | ||||

| (Intercept) | 2.47 | 0.42 | ||

| Prime Type | 0.96 | 0.41 | 2.38 | < .05 |

| Verb | −0.12 | 0.33 | −0.34 | .73 |

| Prime Type × Verb | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.01 | .99 |

| Transitive: PWA | ||||

| (Intercept) | 2.56 | 0.62 | ||

| Prime type | 2.65 | 0.82 | 3.21 | < .01 |

| Verb | −0.17 | 0.41 | −0.41 | .68 |

| Prime Type × Verb | −0.22 | 0.62 | −0.35 | .73 |

| Dative: HOA vs. PWA | ||||

| (Intercept) | 2.57 | 0.43 | ||

| Prime Type | 0.10 | 0.45 | 2.22 | < .05 |

| Verb | 0.37 | 0.35 | 1.05 | .29 |

| Group | 1.44 | 0.90 | 1.60 | .11 |

| Prime Type × Verb | −0.02 | 0.5 | −0.05 | .96 |

| Prime Type × Group | −1.10 | 0.72 | −1.54 | .12 |

| Verb × Group | −0.59 | 0.59 | −1.01 | .31 |

| Prime Type × Verb × Group | 0.05 | 0.87 | 0.06 | .95 |

| Dative: HOA | ||||

| (Intercept) | 2.61 | 0.45 | ||

| Prime Type | 1.00 | 0.39 | 2.54 | < .05 |

| Verb | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.38 | .70 |

| Prime Type × Verb | −0.19 | 0.53 | −0.37 | .71 |

| Dative: PWA | ||||

| (Intercept) | 5.10 | 1.3 | ||

| Prime Type | −0.92 | 0.81 | −1.14 | .25 |

| Verb | −1.27 | 0.61 | −2.10 | < .05 |

| Prime Type × Verb | 0.30 | 0.70 | 0.43 | .67 |

Note. HOAs = healthy older adults; PWA = persons with aphasia.

For dative targets, the model comparing groups revealed that only the effect of prime type was significant, indicating more PO responses were produced overall after PO primes than after DO primes. No other main effect or interaction was significant. Within-group models revealed that HOAs showed comparably significant priming between the same-verb (4% difference, d = 0.22) and different-verb conditions (5% difference, d = 0.32), as indicated by the effect of prime type in the absence of a significant interaction between verb and prime type. Both effect sizes were small (Cohen, 1992). For PWAs, the effect of prime type failed to reach significance again, similar to Experiment 1, although their mean magnitudes of priming effects appear to be similar to those seen in HOAs (5% difference, d = 0.30 for same-verb primes; 4% difference, d = 0.24 for different-verb primes). This may be due to increased variability in the data from PWAs (see Figure 5). In addition, there was a significant effect of verb type, but no significant Verb × Prime interaction.

To summarize, when two unrelated utterances intervened between prime and target, HOAs demonstrated small but significant abstract priming effects, but no lexical boost, for both transitive and dative target structures. Hence, the lexical boost effect that HOAs showed for transitives in Experiment 1 dissipated over two intervening sentences in Experiment 2. PWAs showed significant abstract priming in transitives, with the effect being comparable to HOAs. However, as in Experiment 1, PWAs failed to show significant priming for dative targets. We now turn to implications of the current findings.

General Discussion

Structural priming effects have played a central role in revealing cognitive processes supporting efficient grammatical encoding and language learning in unimpaired speakers. Despite increasing interest in studying structural priming with PWAs as a means to ameliorate their grammatical encoding deficits, it remains largely unknown if and how linguistic and nonlinguistic factors influence the strength and longevity of priming in aphasia. To answer a set of important questions regarding the mechanisms of structural priming in aphasia, this study examined the effects of same- versus different-verb primes on the production of transitive and dative sentences in a group of PWAs and HOAs. We examined these mechanisms in both immediate (0-lag, Experiment 1) and lasting (2-lag, Experiment 2) priming conditions.

The first question examined whether structural priming in aphasia remains preserved in a dialogue-like comprehension-to-production task. Our PWAs showed significant priming effects at least for transitive sentences. This priming was observed not only in Experiment 1 but also over intervening linguistic material in Experiment 2. These findings provide the first evidence suggesting that comprehension-to-production priming remains preserved and operative in the context of dialogue for PWAs beyond a single-speaker experimental task (as used in most previous studies with aphasia). The findings also inform our previous study (Lee, Man, et al., 2019), where we failed to find significant priming for PWAs in a comprehension-based dialogue task. Because the current results demonstrated that the priming mechanism in a comprehension-to-production dialogue-like task is operative at least up to two intervening utterances for our participants with aphasia, it is most likely that the null results from Lee, Man, et al. (2019) are caused by the increased intervening linguistic material associated with the blocked priming paradigm. Further investigation is needed in order to more precisely delineate the extent to which priming is persistent in PWAs in dialogue-like tasks. Nonetheless, the current findings overall suggest that comprehension-based prior linguistic experiences could effectively bias preferences in syntactic production in PWAs indicating that abstract syntactic representations remain intact and are shared between modalities in aphasia (Branigan & Pickering, 2017; Lee, Man, et al., 2019). Furthermore, the ability to extract and reuse the message–syntax mappings from incoming auditory linguistic input remains preserved in PWAs, consistent with previous evidence suggesting that the grammatical encoding deficits in aphasia are a result of inefficient information processing rather than a loss of linguistic representations (de Roo, Kolk, & Hofstede, 2003; Haarmann & Kolk, 1991; Kolk & Van Grunsven, 1985; Lee et al., 2015; Linebarger et al., 2000).

The second question examined the mechanisms at work if PWAs demonstrate priming in a dialogue-like context. More specifically, it was examined whether PWAs show both lexically independent abstract priming and the verb-specific lexical boost when primes and targets are processed consecutively in Experiment 1, as shown in priming studies with unimpaired speakers, including young adults and children. The results revealed that only abstract priming is preserved for PWAs, whereas both abstract priming and lexical boost (for transitives) are operative for HOAs. HOAs showed significant abstract priming in both transitives and datives. They also showed a robust lexical boost in transitives as evidenced by an average of 23% boost in priming following same- versus different-verb primes. This is comparable to a 26.1% lexical boost found in older adults (Hardy, Messenger, & Maylor, 2017) and a 20% lexical boost seen in children (Branigan & McLean, 2016) using a similar dialogue-like task. HOAs showed a trend for lexical boost (7% increase) in datives, though the difference was not statistically significant.

In contrast to HOAs, PWAs did not show evidence of a lexical boost. Even when PWAs showed robust abstract priming for transitives in Experiment 1, they showed an average of only 4% of verb-specific enhancement on priming. These results are consistent with our previous comprehension priming study, wherein PWAs showed only abstract priming during interpretation of syntactically ambiguous sentences (Lee, Hosokawa, et al., 2019). Furthermore, the findings suggest that the lexically independent and lexically specific structural priming effects are associated with distinctive cognitive processes (Chang et al., 2012; Reitter et al., 2011) and can be selectively affected in PWAs. The lack of lexical boost may be attributed to PWAs' deficits in spreading activation of lexical information (Reitter et al., 2011) or maintaining lexical–semantic information in short-term memory (Chang et al., 2006, 2012). Of relevance, our PWAs showed significantly lower performance than HOAs on the lexical–semantic short-term memory tests of the TALSA (see Table 2; see also Allen et al., 2012; Barde et al., 2010; Martin & Ayala, 2004). However, Yan et al. (2018) found a significant lexical boost in PWAs whose lexical–semantic short-term memory was impaired, highlighting the need for caution on this interpretation. As noted in the introduction, Yan et al. used a priming task where their PWAs orally repeated the heard prime sentence and then read a written version to verify if their repetition was correct. This increased depth of encoding for the prime sentences in their study might have allowed PWAs to better activate and maintain the lexical information in memory and reuse it in subsequent sentence production more effectively than in the current study, compensating for their limitations in lexical–semantic short-term memory. Further investigation is needed to better delineate how task complexity and individuals' nature and severity in lexical–semantic processing modulate a lexically specific boost in priming.

Third, in Experiment 2, we investigated if priming effects are persistent over intervening linguistic material to determine if comprehension-induced priming in a dialogue setting reflects enduring facilitation or “learning” in syntactic production as proposed by previous studies with unimpaired speakers (Bock & Griffin, 2000; Chang et al., 2006, 2012; Reitter et al., 2011; see also T. F. Jaeger & Snider, 2013). The results of Experiment 2 by and large supported this view. For transitive targets, both HOAs and PWAs showed significant abstract priming effects over intervening utterances, though the effects were substantially smaller compared to Experiment 1 for both groups. The lexical boost effect that was significant in Experiment 1 for HOAs dissipated over the intervening fillers in Experiment 2, consistent with previous production priming studies showing a short-lived time course of lexical boost in young adults and children (Branigan & McLean, 2016; Hartsuiker et al., 2008; Kaschak & Borreggine, 2008; Malhotra, Pickering, Branigan, & Bednar, 2008). Similarly, PWAs continued to show abstract priming in transitives, and notably, they did not differ from HOAs in the magnitude of priming, suggesting that lasting abstract priming in PWAs is as effective as that in HOAs. For dative targets, HOAs continued to show small but reliable abstract priming, whereas the priming effect for PWAs did not reach significance in the mixed-effects models (see below for discussion of the absence of priming effects in datives).

The preserved abstract priming effect over a lag found in our PWAs, at least for transitives, suggests that simply hearing (and likely comprehending) the interlocutor's sentences could create enduring changes in the syntactic production system of PWAs. It is beyond the scope of the current study to determine if the lasting priming effect in PWAs is a consequence of implicit error-based learning in the sequencing system (Chang et al., 2006, 2012) or changes in base-level activation for the target message–structure associations (Reitter et al., 2011). However, the findings clearly show that priming effects are persistent and reflect more than a temporary boost of syntactic structures in PWAs, extending previous priming studies that have proposed use of structural priming as an intervention strategy for syntactic deficits in aphasia (Cho-Reyes et al., 2016; Lee, Hosokawa, et al., 2019; Lee & Man, 2017; Lee, Man, et al., 2019). Furthermore, the present results suggest that the dialogue priming paradigm can be employed as a treatment of syntactic processing that approximates conversational interaction, departing from existing treatment approaches (e.g., Treatment of Underlying Forms and Mapping Therapy) involving explicit training of linguistic representations and operations (Rochon et al., 2005; Schwartz et al., 1994; Thompson et al., 2003; Thompson & Shapiro, 2005).

It is worth noting that PWAs failed to show reliable priming effects for datives in both experiments, in contrast with the significant abstract priming effects seen in transitives. Some prior studies with young adults also reported discrepancies between the transitive and dative structures (see Bock & Griffin, 2000, for a review; Bock, 1986; Bock & Loebell, 1990; Hartsuiker & Kolk, 1998b). The PWAs tested in Saffran and Martin (1997; see also Yan et al., 2018) showed priming only in transitives, but not in datives in the experimental testing session, although they showed some increase in use of datives in spontaneous speech in a postexperimental session (cf. Hartsuiker & Kolk, 1998a). The disparity in the priming effects between transitives and datives may be a consequence of prediction error-based learning mechanisms of structural priming wherein unexpected word orders instantiate greater priming or “learning” in the individual (Chang et al., 2006, 2012; T. F. Jaeger & Snider, 2013). Passive sentences are considerably less frequent than active sentences, and PWAs would therefore not expect them to occur during comprehension (St. John & Gernsbacher, 2013). Moreover, our transitive alternations involved semantically reversible sentences (both agent and theme were animate), which are difficult to produce spontaneously in PWAs (Cho & Thompson, 2010; Saffran et al., 1980a, 1980b). Thus, our PWAs would experience greater prediction errors during comprehension of the passive primes, resulting in a stronger priming effect for transitives. In contrast, because DO sentences are only slightly less frequent than PO sentences, the error between what the individual would predict and what they actually hear is smaller, which in turn might have resulted in nonsignificant priming for datives in our PWAs. Another reason for this discrepancy could be due to greater pragmatic saliency associated with transitive, passive/active alternations compared to dative, PO/DO alternations (Hartsuiker & Kolk, 1998b; see Bock & Griffin, 2000, for other accounts). Because transitive alternations involve change of subjecthood, shifting focus of attention among interlocutors, these alternations may highlight pragmatic aspects of the task to a greater extent than dative alternations. This increased pragmatic saliency might have nicely aligned with the goal-driven interactive nature of our dialogue-like task, encouraging our participants to echo the experimenter's syntactic choices to a greater extent than in the case of datives. Further research is needed to better test these hypotheses.

In conclusion, although there is increasing interest in using structural priming to facilitate syntactic production in aphasia, the extent to which the mechanisms of structural priming are preserved and enduring remains largely unknown. This study was a systematic investigation of the mechanisms of lexically independent and lexically specific priming in a dialogue-like comprehension-to-production task, above and beyond previous structural priming studies in aphasia. A set of important findings were obtained. Our PWAs demonstrated preserved comprehension-to-production priming in a dialogue-like task, at least for transitive targets. In Experiment 1, when prime and target were processed consecutively, only abstract priming was preserved. The abstract priming persisted over intervening fillers, indicating that dialogue-based structural priming creates enduring effects in the grammatical encoding system of aphasia, possibly reflecting intact syntactic learning in PWAs. Collectively, the current findings indicate that syntactic representations are shared between modalities and remain intact in aphasia and that it may be feasible to use a dialogue-like comprehension-to-production priming as a means to strengthen weakened message–syntax mapping in aphasia.

Acknowledgments

This research was, in part, supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R21DC015868 (awarded to J. L.). We thank our participants with aphasia and their caregivers for their participation and members of the Purdue Aphasia Lab, specifically Joslyn Burke, Alayna Ging, Hannah Haworth, and Linnea Rohrsen, for their assistance with data analysis.

Funding Statement

This research was, in part, supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R21DC015868 (awarded to J. L.).

Footnotes

These “lenient” criteria applied to only 4% (6/153) of all correct passive responses produced by PWA.

Because the participants completed both experiments (although the order of the experiments was counterbalanced and there was at least a 2-week interval between experiments), we ran a set of additional models to rule out the significant priming effects being influenced by some participants' prior completion of a similar experiment (practice effect). Experiment order and prime and their interaction were included as fixed factors. Only for the transitive targets of Experiment 2, experiment order interacted with prime, but in the direction that those who completed Experiment 2 first showed greater priming effects than those who completed Experiment 1 first (p < .01). Therefore, the results are unlikely to be due to practice effects.

References

- Allen C. M., Martin R. C., & Martin N. (2012). Relations between short-term memory deficits, semantic processing, and executive function. Aphasiology, 26(3–4), 428–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barde L. H., Schwartz M. F., Chrysikou E. G., & Thompson-Schill S. L. (2010). Reduced short-term memory span in aphasia and susceptibility to interference: Contribution of material-specific maintenance deficits. Neuropsychologia, 48(4), 909–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaanse R., & van Zonneveld R. (2005). Sentence production with verbs of alternating transitivity in agrammatic Broca's aphasia. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 18(1), 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D., Maechler M., Bolker B., & Walker S. (2014). lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R Package Version, 1(7), 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bock K. (1986). Syntactic persistence in language production. Cognitive Psychology, 18(3), 355–387. [Google Scholar]

- Bock K. (1989). Closed-class immanence in sentence production. Cognition, 31(2), 163–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock K., Dell G. S., Chang F., & Onishi K. H. (2007). Persistent structural priming from language comprehension to language production. Cognition, 104(3), 437–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock K., & Griffin Z. M. (2000). The persistence of structural priming: Transient activation or implicit learning? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 129(2), 177–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock K., & Loebell H. (1990). Framing sentences. Cognition, 35(1), 1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branigan H. P., & McLean J. F. (2016). What children learn from adults' utterances: An ephemeral lexical boost and persistent syntactic priming in adult–child dialogue. Journal of Memory and Language, 91, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Branigan H. P., & Pickering M. J. (2017). Structural priming and the representation of language. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branigan H. P., Pickering M. J., McLean J. F., & Cleland A. A. (2007). Syntactic alignment and participant role in dialogue. Cognition, 104(2), 163–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branigan H. P., Pickering M. J., & Cleland A. A. (2000). Syntactic co-ordination in dialogue. Cognition. Cognition, 75(2), B13–B25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branigan H. P., Pickering M. J., Stewart A. J., & McLean J. F. (2000). Structural priming in spoken production: Linguistic and temporal interference. Memory & Cognition, 28(8), 1297–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramazza A., & Berndt R. S. (1985). A multicomponent deficit view of agrammatic Broca's aphasia. In Agrammatism (pp. 27–63). Orlando, FL: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caramazza A., & Miceli G. (1991). Selective impairment of thematic role assignment in sentence processing. Brain and Language, 41(3), 402–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang F., Dell G. S., & Bock K. (2006). Becoming syntactic. Psychological Review, 113(2), 234–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang F., Janciauskas M., & Fitz H. (2012). Language adaptation and learning: Getting explicit about implicit learning. Language and Linguistics Compass, 6(5), 259–278. [Google Scholar]

- Cho S., & Thompson C. K. (2010). What goes wrong during passive sentence production in agrammatic aphasia: An eyetracking study. Aphasiology, 24(12), 1576–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho-Reyes S., Mack J. E., & Thompson C. K. (2016). Grammatical encoding and learning in agrammatic aphasia: Evidence from structural priming. Journal of Memory and Language, 91, 202–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho-Reyes S., & Thompson C. K. (2012). Verb and sentence production and comprehension in aphasia: Northwestern Assessment of Verbs and Sentences (NAVS). Aphasiology, 26(10), 1250–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland A. A., & Pickering M. J. (2003). The use of lexical and syntactic information in language production: Evidence from the priming of noun-phrase structure. Journal of Memory and Language, 49(2), 214–230. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland A. A., & Pickering M. J. (2006). Do writing and speaking employ the same syntactic representations? Journal of Memory and Language, 54(2), 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roo E., Kolk H., & Hofstede B. (2003). Structural properties of syntactically reduced speech: A comparison of normal speakers and Broca's aphasics. Brain and Language, 86(1), 99–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap W. P., Cortina J. M., Vaslow J. B., & Burke M. J. (1996). Meta-analysis of experiments with matched groups or repeated measures designs. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 170–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira V. S., & Bock K. (2006). The functions of structural priming. Language and Cognitive Processes, 21(7–8), 1011–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine A. B., & Florian Jaeger T. (2013). Evidence for implicit learning in syntactic comprehension. Cognitive Science, 37(3), 578–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruberg N., Ostrand R. O., Momma S., & Ferreira V. S. (2019). Syntactic entrainment: Repetition of syntactic structure in event descriptions. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gruberg N., Wardlow L., & Ferreira V. S. (2019). Learning syntactic restrictions in childhood and adulthood. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Haarmann H. J., & Kolk H. H. (1991). Syntactic priming in Broca's aphasics: Evidence for slow activation. Aphasiology, 5(3), 247–263. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy S. M., Messenger K., & Maylor E. A. (2017). Aging and syntactic representations: Evidence of preserved syntactic priming and lexical boost. Psychology and Aging, 32(6), 588–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartsuiker R. J., Bernolet S., Schoonbaert S., Speybroeck S., & Vanderelst D. (2008). Syntactic priming persists while the lexical boost decays: Evidence from written and spoken dialogue. Journal of Memory and Language, 58(2), 214–238. [Google Scholar]

- Hartsuiker R. J., & Kolk H. H. (1998a). Syntactic facilitation in agrammatic sentence production. Brain and Language, 62(2), 221–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartsuiker R. J., & Kolk H. H. (1998b). Syntactic persistence in Dutch. Language and Speech, 41(2), 143–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm-Estabrooks N. (2001). Cognitive Linguistic Quick Test: Examiner's manual (CLQT). New York: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger F. T. (2008). Categorical data analysis: Away from ANOVAs (transformation or not) and towards logit mixed models. Journal of Memory and Language, 59, 434–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]