Abstract

Early environmental exposure is recognized as a key factor for long-term health based on the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease hypothesis. It considers that early-life nutrition is now being recognized as a major contributor that may permanently program change of organ structure and function toward the development of diseases, in which epigenetic mechanisms are involved. Recent researches indicate early-life environmental factors modulate the microbiome development and the microbiome might be mediate diet-epigenetic interaction. This review aims to define which nutrients involve microbiome development during the critical window of susceptibility to disease, and how microbiome modulation regulates epigenetic changes and influences human health and future prevention strategies.

Keywords: disease development, fetal reprogramming, gut microbiome, nutrition

Introduction

In 1986, David Barker proposed the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis, denoted fetal reprogramming, that the environmental stimuli such as nutrients during vulnerable development stages may permanently program change of organ structure and function of the offspring toward the development of non-communicable diseases [1]. Since Barker’s observation, denoted fetal programming, it is widely recognized that nutrient during pregnancy and lactation is one of the modifiable risk factors for adult chronic diseases including diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [2]. Following the DOHaD concept, early-life environmental factors such as nutrients may modulate the development of the gut microbiota [3]. It is postulated that the gut microbiome can be shaped by nutrients, which induce epigenetic changes prior to fetal and infant programming of disease.

In this review, we describe how early nutrients link microbiome modulation and influence the early epigenome. We refer the term “early-life” to the period from pregnancy to 2 years of age. Moreover, we assess the early-life gut microbiome as epigenetic modifiers are associated with early-onset or adult diseases including metabolic disorders. In detail, section 2 reviews the regulation of epigenetic mechanisms for metabolic signaling through nutrients and their metabolites as epigenetic substrates or cofactors. Section 3 provides several early environmental factors that may modulate early microbial communities. Section 4 describes the effects of each nutrient on gut microbiome changes in early-life through epigenetic mechanisms and the potential role of the gut microbiome in adult disease.

The Link between Dietary Epigenetic Modulator and Metabolic Processes

Epigenetic changes by environmental conditions enhance cellular plasticity [4]. Genomic DNA is packed into chromatin with histone protein and the changes of chromatin structure participate in the cellular processes in response to physiological signals. Chromatin structure is determined by epigenetic modification resulting in transcription and replication types of machinery and therefore influences biological consequences [5]. Epigenetic changes produce DNA, histone and chromatin modifications including methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, sumoylation, and ubiquitination with modifying enzymes (e.g., methyltransferases) [6]. Non-coding RNA is an epigenetic mark that mediates epigenetic modification by environmental factors such as diet. Modification of chromatin architecture by epigenetic marks can be heritable and modify the risks of disease in later life (Table 1) [7-17].

Table 1.

Epigenetic modifications and their functions with nutrients

| Target | Residue | Modification | Major function | Related nutrients | Related microbiome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | CpG | me | Transcriptional repression | Folate, choline, omega3-PUFA, polyphenols, proteins, high-fat diet | Bifidobacterium | [7,8] |

| Lactobacterium | ||||||

| Bacteroids | ||||||

| K4 | me1, me2, me3 | Transcriptional activation, poised to transcriptional activation | Low-fat diet, riboflavin, polyphenols, cobalamin | Firmicutes | [9,10] | |

| Lachnospiraceae | ||||||

| K27 | me1 | Transcriptional activation | Omega3-PUFA | Firmicutes | [11-13] | |

| high-fat diet | Bacteroidestes | |||||

| Nicotinamide | Akkermansia | |||||

| me2 | Transcriptional activation, enhancer silencing | Verrucomicrobia | ||||

| me3 | Transcriptional repression | Bifidobacteriaceae | ||||

| K9, K4, K14, K36 | ac | Transcriptional activation | Omega3-PUFA, selenium, SCFAs, ellagic acid, high-fat diet | Bifidobacterium | [9,14,15] | |

| Anaerostipes | ||||||

| Eubacterium | ||||||

| Histone H4 | K16 | ac | Transcriptional activation and repression for DNA repair | Curcumin | Clostridium | [16] |

| Firmicutes | ||||||

| Bacteriodetes | ||||||

| K4, K8, K12 | ac | Transcriptional activation | SCFAs, folate, biotin | Bifidobacterium | [17] | |

| Lactobacillus | ||||||

| Bacteroides |

me, methylation (1, mono; 2, bi; 3, tri); PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; ac, acetylation; SCFA, short chain fatty acid.

Several metabolites or cofactors of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycles involved in methylation or demethylation of histone [18]. The epigenetic modifying enzymes use some energy metabolites in one-carbon metabolism with S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) and TCA cycles. SAM is generated through one-carbon metabolism and a key factor for epigenetic processes. DNA methylation requires the SAM as a methyl donor, while ten-eleven translocation and Jumonji C domain-containing proteins-mediated demethylation requires TCA cycle metabolite α-ketoglutarate and Fe2+ as a cofactor. DNA and histone demethylation have the potential to regulate diverse physiological functions, including metabolic signaling [19].

There are several known dietary methyl donors including folate, choline, and vitamin B12 participate in one-carbon metabolism and these nutrients have been examined for the epigenetic regulation in animal and human studies [2]. Methyl donors are related to energy production and amino acid metabolism, therefore nutritional imbalance as the disruption of the one-carbon cycle may participate in the development of metabolic diseases. Besides, many studies have shown that the mechanism of developmental reprogramming is involved in dietary availability of methyl donors [2].

Histone (de)methylation is one of the mechanisms involved in several diseases including metabolic syndrome and cancer [20]. Lysine methylation of a specific site of H3 acts both transcriptional activation (H3K4) and silencing (H3K9, H3K27) for regulating gene expression by a degree of methylation within the histone tail. The H3K9 specific demethylase JmjC domain-containing histone demethylase 2A (JHDM2A) was well known to an important regulator of fatty acid metabolism, therefore loss of function of JHDM2A resulted in obesity and hyperlipidemia [21,22]. H3K4 demethylase LSD1 using flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) as a cofactor, epigenetically represses energy expenditure, which facilitates energy storage as triglycerides in white adipocytes [23]. FAD is also related to the TCA cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, and fatty acid β-oxidation with riboflavin (vitamin B2) in the cytoplasm and mitochondria [24].

Arginine methylation of histone has been rapidly highlighted over the years for the role of diseases [9]. Protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) with SAM as a methyl donor, transfer of methyl groups to specific arginine residues in histone and nonhistone protein substrates, resulting in the byproduct S-adenosyl-homocysteine (SAH). The SAM/SAH ratio can reflect the cellular methylation potential, which interacted with PRMTs. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α (PGC-1α; encoded by the PPARGC1A) serves as a transcriptional coactivator in mitochondria and has a function in oxidative metabolism. PRMT1 mediated cytosine methylation in PGC-1α which is expressed in brown adipose tissue involved in energy metabolism and diabetes [25].

Acetylation of histone H3 and H4 is mediated by acetyl-CoA and NAD+ for cellular metabolism. Lysine acetylation occurs in proteins involved in glycolysis, pyruvate metabolism and the TCA cycle [26]. Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a deacetylase depending on NAD+ has emerged as a key metabolic sensor linking to metabolic homeostasis, and SIRT1 participates the regulation of glucose homeostasis under nutrient deficiency [27]. For example, SIRT1 modulates acetylation on H3K9/K14 at circadian clock-controlled gene promoters through a high-fat diet [28]. It is reported that acetyl-CoA dependent histone acetylation may have an important role in the cellular assessment of metabolic states and circadian clock [29]. Therefore, nutrients (e.g., pyruvate, fatty acids, or branched-chain amino acids) involved in acetyl-Co A levels can modulate metabolic signaling.

Nutrients driven O-GlcNAc (N-acetylglucosamine) glycosylation has emerged as an important chromatin modification process [30,31]. O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) is a key enzyme through protein glycosylation in the Hexosamone Biosynthetic Pathway. Several studies reported that nutrients-sensing GlcNAcylation of histone proteins has involved in chromatin remodeling and regulation of biological processes [32]. Chromatin GlcNAcylation depend on the cellular processes with glucose, glutamine, fatty acid and ATP metabolism. High fat diet induced insulin resistance, hyperphagia and obesity through O-GlcNAc cycling [33,34]; thus, OGT can be a sensor for adipose to brain axis to target obesity [34].

Environmental Factors Involved in Early-Life Development of Microbiome

The early-life microbiota contains a unique microbial communities consisting of numerous bacteria and viruses. This microbiota has identified by using different kinds of technologies including 16S rRNA sequencing. The gut microbiota is linked to risk for various conditions in inflammatory diseases, asthma, obesity, glucose intolerance, and type 2 diabetes [35-37].

Over the last decades, the paradigm of a sterile condition in utero is shifting to the possibility of the prenatal maternal-fetal coexist with commensal and symbiotic microbes [38]. Recent studies also support a prenatal microbial milieu through bacterial presentation in placenta, amniotic fluid, umbilical cord, and meconium [39]. In addition, there are emerging reports of the prenatal microbial composition on fetal and postnatal development. However, concerns have raised by molecular based approaches, therefore it is needed for appropriate controls to account for DNA contamination or bacterial viability [40].

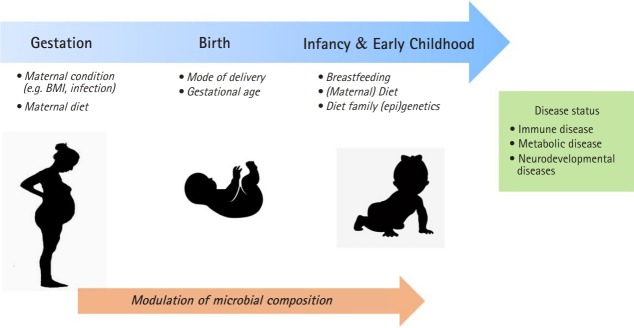

A maternal condition during pregnancy and postnatal period can provide a critical window for susceptibility to microbiome development through the environmental factors such as mode of delivery and maternal diet (Fig. 1). The delivery mode has a crucial function in the early gut microbiota composition. Infants by vaginally delivery have higher levels of intestinal Bacteroides, Lactobacilli, and Bifidobacterium, which are commonly present in vaginal route, whereas infants by caesarean section (C-section) have higher level of Enterococcus, and Clostridium from skin, oral or hospital environment [41]. C-section born infants have shown to an increased risk of immune disorder such as asthma and allergy and obesity [42,43]. It has been revealed that neonates born by C-section exhibited significantly higher global DNA methylation levels in leucocytes [44] and CD34+ cell [45] compared with those born vaginally.

Fig. 1.

The critical window in early-life for microbiome modulation may influence on development of diseases later in life. BMI, body mass index.

Gestational age is another important influencer for gut microbiome development [7,8]. It was reported that the gut microbiota of preterm infants has shown to delayed colonization by limited microbial diversity and ths risk of gut dysbiasis. The gut microbiota composition of preterm infants has Enterobacter, Enterococcus, Escherichia, and Klebsiella predominantly and relatively low level of gammaproteobacteria than those in full term infants [46].

Breastfeeding have been reported to influence the infant microbiota. It was reported that microbiome involved the effects of DNA methylation through breast milk, which influences the gut microbiome community composition. Breastfeeding during this period is associated with greater Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium, which are folate producers, thereby affecting DNA methylation regulated by methyl-donor [47]. Also, breast milk oligosaccharides alter hut microbiome community that secrete short-chain fatty acid. Therefore, the strain of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus by breastfeeding could make intestinal contents more acidic with short-chain fatty acids, which modulate a defense mechanism against pathogens and epigenetic effects [48].

Maternal Nutrients Influence on Microbiome and Epigenetic Modulation

As mentioned above, early environmental factors such as nutrition may have interacted with gut microbiome. Also, the microbial metabolites such as B vitamins, short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), polyphenols (ellagic acid, urolithin, equol, isothiocyanate), and omega3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) are reported to influence epigenetic mechanisms [49,50]. Maternal gut microbe metabolites can change the host cellular levels of important epigenetic modifiers like histone acetyl transferases (HATs), histone deacetylases (HDACs), DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), and DNA demethylases [51].

A number of the vitamins cannot be synthesized by the human body, therefore must be obtained by the diet. The gut microbiome is one of the important sources of B vitamins for the host [52]. Vitamins B2, B6, B9, and B12 are important cofactors for the enzymes in the folate cycle where the conversion from homocysteine to methionine is required for the availability of SAM. Therefore, these vitamins could affect histone methyl transferasess and DNMTs for histone and DNA methylation. The other gut microbial metabolites such as vitamins B3, B5, and SCFAs are sources of acetyl-CoA or NAD, which affect histone acetylation via sirtuin inhibition or HAT activation [51].

The microbial SCFAs from the fermentation of dietary fiber were shown to maintain the nervous and immune systems through epigenetic modification [17,53]. The SCFA acetate and butyrate are the most abundant in the intestinal tract and can be produced with acetyl-CoA which is universal acetyl group donor for histone acetylation. Maternal acetate suppressed asthma by Treg and Foxp3 through HDAC9 inhibition [54]. Besides, the SCFA butyrate induced global histone acetylation and activation in FOXO3A and MT2 by inhibiting HDAC1 and HDAC2 [55]. The SCFA pentanoate produced by gut microbiota such as Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus affects the use of the acetyl-CoA pool for histone acetylation [56] that inhibits HDAC1 and HDAC8 in CD4+ T cell, thereby reduce interleukin (IL)-17A production and enhance IL-10 production [56].

Polyphenols have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immune-modulatory effects. Maternal supplementation of polyphenols improved the early development of the risk of intrauterine growth restriction [57]. Urolithins are microbial metabolites from ellagic acid (one of the polyphenols) that are reported to have a protective effect on chronic diseases such as metabolic syndrome [58] and decrease triglyceride accumulation in adipocytes [14]. Ellagic acid was reported to inhibit reduction of HDAC activity and urolithins prevented HAT activity [15]. Recent studies were shown that urolithin bacteria are Bifidobacterium, pseudocatenulatum, Lactobacilli, and Coriobacteriaceae (Gordonibacter) [59] and Eggerthellaceae family [60]. Equol produced by the intestinal bacterium Lactococcus reduced the risk of cardiovascular diseases including low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and arterial stiffness [61].

Omega-3 PUFAs are also obtained by the diet and have been interacted with gut microbiota. Maternal omega-3 PUFAs are a key role in the immune system of the infant through the epigenetic mechanism for DNA and histone methylation [11,62]. For the epigenetic mechanism, it was reported that maternal omega-3 PUFA induced changing of methylation level in differentially methylated regions [12] and the promoter methylation level of Interferon γ and IL13 [62]. Maternal omega-3 PUFAs regulated offspring obesity through recomposition of the gut microbiota, Epsilonproteobacteria, Bacteroides, Akkermansia, and Clostridia [63]. High- fat diet promotes intestinal epithelial HDAC3 level and SCFA butylate supplementation reduced HDAC3 activity [64]. Similarly, maternal high fat diet decreased fecal SCFA propionate and butylate level and increased Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio, Akkermansia, and Verrucomicrobia in the offsprings related to blood pressure [65].

Maternal over-nutrition and undernutrition have shown to increase predisposition to obesity and epigenetic changes in offspring [2,66]. Such maternal malnutrition disrupted the stable microbial community, and less bacterial richness and diversity, which is linked to increased risk of inflammatory diseases and obesity [67-70]. The maternal high fat diet was associated with alterations in the gut microbiome profiles of offspring for Coprococcus, Coriobacteriacae, Helicobacterioceae, and Allobaculum [71], the ratio of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes [72] in mice, Campylobacter in Macaca fuscata [13] and Bacteroides in humans [73]. For the epigenetic mechanism, it was reported that the high-fat diet affected HNF4ɑ binding sites at acetylated histone H3K27 in colon epithelium [10] and decreased Bifidobacteriaceae [74]. Similarly, over-weighted woman during pregnancy had higher Bacteroids and lower Phascolarctobacterium than a normal-weighted woman during pregnancy [75]. Under-nutrition group in school-age children had a higher level of the Firmicutes and Lachnospiraceae [76]. Besides, maternal supplementation of probiotics with Lactobacillus rhamnousus or Bifidobacterium lactis induced interferon-gamma production on cord blood compared to controls [77].

Conclusion

The interaction between the developing gut microbiome and epigenetic processes is an important mechanism of developmental reprogramming of immune disorder, obesity, and metabolic disorders. There are mounting evidence supporting that gut microbiota may modify the pattern of DNA methylation and histone modification. Recent studies have shown that the gut microbiome produces plenty of metabolites come from maternal nutrients that have the potential to modulate DNA methylation and histone modification. Maternal nutrients may have a crucial role in early development and long term health consequences. This review explored the impact of maternal nutrients on epigenetic mechanisms that regulate the early-life microbiome profile. The importance of individual nutrients induced by epigenetic modulation will help achieve optimal gut microbiota and strategy for improving health consequences.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Barker DJ, Osmond C. Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischaemic heart disease in England and Wales. Lancet. 1986;1:1077–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee HS. Impact of maternal diet on the epigenome during In utero life and the developmental programming of diseases in childhood and adulthood. Nutrients. 2015;7:9492–9507. doi: 10.3390/nu7115467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stiemsma LT, Michels KB. The role of the microbiome in the developmental origins of health and disease. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20172437. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vineis P, Chatziioannou A, Cunliffe VT, Flanagan JM, Hanson M, Kirsch-Volders M, et al. Epigenetic memory in response to environmental stressors. FASEB J. 2017;31:2241–2251. doi: 10.1096/fj.201601059RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid MA, Dai Z, Locasale JW. The impact of cellular metabolism on chromatin dynamics and epigenetics. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:1298–1306. doi: 10.1038/ncb3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011;21:381–395. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho NT, Li F, Lee-Sarwar KA, Tun HM, Brown BP, Pannaraj PS, et al. Meta-analysis of effects of exclusive breastfeeding on infant gut microbiota across populations. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4169. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06473-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korpela K, Blakstad EW, Moltu SJ, Strommen K, Nakstad B, Ronnestad AE, et al. Intestinal microbiota development and gestational age in preterm neonates. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2453. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20827-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanc RS, Richard S. Arginine methylation: the coming of age. Mol Cell. 2017;65:8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin Y, Roberts JD, Grimm SA, Lih FB, Deterding LJ, Li R, et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome reprograms the intestinal epigenome and leads to altered colonic gene expression. Genome Biol. 2018;19:7. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1389-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costantini L, Molinari R, Farinon B, Merendino N. Impact of omega-3 fatty acids on the gut microbiota. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E2645. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dijk SJ, Zhou J, Peters TJ, Buckley M, Sutcliffe B, Oytam Y, et al. Effect of prenatal DHA supplementation on the infant epigenome: results from a randomized controlled trial. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:114. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0281-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma J, Prince AL, Bader D, Hu M, Ganu R, Baquero K, et al. High-fat maternal diet during pregnancy persistently alters the offspring microbiome in a primate model. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3889. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang I, Kim Y, Tomas-Barberan FA, Espin JC, Chung S. Urolithin A, C, and D, but not iso-urolithin A and urolithin B, attenuate triglyceride accumulation in human cultures of adipocytes and hepatocytes. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016;60:1129–1138. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang I, Buckner T, Shay NF, Gu L, Chung S. Improvements in metabolic health with consumption of ellagic acid and subsequent conversion into urolithins: evidence and mechanisms. Adv Nutr. 2016;7:961–972. doi: 10.3945/an.116.012575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Z, Chen Y, Xiang L, Wang Z, Xiao GG, Hu J. Effect of curcumin on the diversity of gut microbiota in ovariectomized rats. Nutrients. 2017;9:E1146. doi: 10.3390/nu9101146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stiemsma LT, Turvey SE. Asthma and the microbiome: defining the critical window in early life. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2017;13:3. doi: 10.1186/s13223-016-0173-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salminen A, Kauppinen A, Hiltunen M, Kaarniranta K. Krebs cycle intermediates regulate DNA and histone methylation: epigenetic impact on the aging process. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;16:45–65. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cardaci S, Ciriolo MR. TCA cycle defects and cancer: when metabolism tunes redox state. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:161837. doi: 10.1155/2012/161837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mentch SJ, Mehrmohamadi M, Huang L, Liu X, Gupta D, Mattocks D, et al. Histone methylation dynamics and gene regulation occur through the sensing of one-carbon metabolism. Cell Metab. 2015;22:861–873. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inagaki T, Tachibana M, Magoori K, Kudo H, Tanaka T, Okamura M, et al. Obesity and metabolic syndrome in histone demethylase JHDM2a-deficient mice. Genes Cells. 2009;14:991–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tateishi K, Okada Y, Kallin EM, Zhang Y. Role of Jhdm2a in regulating metabolic gene expression and obesity resistance. Nature. 2009;458:757–761. doi: 10.1038/nature07777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hino S, Nagaoka K, Nakao M. Metabolism-epigenome crosstalk in physiology and diseases. J Hum Genet. 2013;58:410–415. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2013.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssen JJ, Grefte S, Keijer J, de Boer VC. Mito-nuclear communication by mitochondrial metabolites and its regulation by B-vitamins. Front Physiol. 2019;10:78. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tzika E, Dreker T, Imhof A. Epigenetics and metabolism in health and disease. Front Genet. 2018;9:361. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu W, Li Y, Liu C, Zhao S. Protein lysine acetylation guards metabolic homeostasis to fight against cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33:2279–2285. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang F, Kume S, Koya D. SIRT1 and insulin resistance. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:367–373. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eckel-Mahan KL, Patel VR, de Mateo S, Orozco-Solis R, Ceglia NJ, Sahar S, et al. Reprogramming of the circadian clock by nutritional challenge. Cell. 2013;155:1464–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aguilar-Arnal L, Sassone-Corsi P. Chromatin landscape and circadian dynamics: Spatial and temporal organization of clock transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:6863–6870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411264111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navarro E, Funtikova AN, Fito M, Schroder H. Prenatal nutrition and the risk of adult obesity: long-term effects of nutrition on epigenetic mechanisms regulating gene expression. J Nutr Biochem. 2017;39:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terasaka T, Otsuka F, Tsukamoto N, Nakamura E, Inagaki K, Toma K, et al. Mutual interaction of kisspeptin, estrogen and bone morphogenetic protein-4 activity in GnRH regulation by GT1-7 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;381:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardiville S, Hart GW. Nutrient regulation of gene expression by O-GlcNAcylation of chromatin. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2016;33:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olivier-Van Stichelen S, Wang P, Comly M, Love DC, Hanover JA. Nutrient-driven O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) cycling impacts neurodevelopmental timing and metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:6076–6085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.774042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li MD, Vera NB, Yang Y, Zhang B, Ni W, Ziso-Qejvanaj E, et al. Adipocyte OGT governs diet-induced hyperphagia and obesity. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5103. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07461-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, Li S, Zhu J, Zhang F, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature11450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perry RJ, Peng L, Barry NA, Cline GW, Zhang D, Cardone RL, et al. Acetate mediates a microbiome-brain-beta-cell axis to promote metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2016;534:213–217. doi: 10.1038/nature18309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanca A, Abbondio M, Palomba A, Fraumene C, Manghina V, Cucca F, et al. Potential and active functions in the gut microbiota of a healthy human cohort. Microbiome. 2017;5:79. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0293-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DiGiulio DB, Romero R, Amogan HP, Kusanovic JP, Bik EM, Gotsch F, et al. Microbial prevalence, diversity and abundance in amniotic fluid during preterm labor: a molecular and culture-based investigation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perez-Munoz ME, Arrieta MC, Ramer-Tait AE, Walter J. A critical assessment of the "sterile womb" and "in utero colonization" hypotheses: implications for research on the pioneer infant microbiome. Microbiome. 2017;5:48. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0268-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milani C, Duranti S, Bottacini F, Casey E, Turroni F, Mahony J, et al. The first microbial colonizers of the human gut: composition, activities, and health implications of the infant gut microbiota. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2017;81:e00036–17. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00036-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kristensen K, Henriksen L. Cesarean section and disease associated with immune function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:587–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huh SY, Rifas-Shiman SL, Zera CA, Edwards JW, Oken E, Weiss ST, et al. Delivery by caesarean section and risk of obesity in preschool age children: a prospective cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:610–616. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schlinzig T, Johansson S, Gunnar A, Ekstrom TJ, Norman M. Epigenetic modulation at birth - altered DNA-methylation in white blood cells after Caesarean section. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:1096–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Almgren M, Schlinzig T, Gomez-Cabrero D, Gunnar A, Sundin M, Johansson S, et al. Cesarean delivery and hematopoietic stem cell epigenetics in the newborn infant: implications for future health? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:502. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arboleya S, Binetti A, Salazar N, Fernandez N, Solis G, Hernandez-Barranco A, et al. Establishment and development of intestinal microbiota in preterm neonates. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012;79:763–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rossi M, Amaretti A, Raimondi S. Folate production by probiotic bacteria. Nutrients. 2011;3:118–134. doi: 10.3390/nu3010118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamburini S, Shen N, Wu HC, Clemente JC. The microbiome in early life: implications for health outcomes. Nat Med. 2016;22:713–722. doi: 10.1038/nm.4142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hullar MA, Fu BC. Diet, the gut microbiome, and epigenetics. Cancer J. 2014;20:170–175. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gerhauser C. Impact of dietary gut microbial metabolites on the epigenome. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2018;373:20170359. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2017.0359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krautkramer KA, Dhillon RS, Denu JM, Carey HV. Metabolic programming of the epigenome: host and gut microbial metabolite interactions with host chromatin. Transl Res. 2017;189:30–50. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoshii K, Hosomi K, Sawane K, Kunisawa J. Metabolism of dietary and microbial vitamin B family in the regulation of host immunity. Front Nutr. 2019;6:48. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dalile B, Van Oudenhove L, Vervliet B, Verbeke K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:461–478. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thorburn AN, McKenzie CI, Shen S, Stanley D, Macia L, Mason LJ, et al. Evidence that asthma is a developmental origin disease influenced by maternal diet and bacterial metabolites. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7320. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shimazu T, Hirschey MD, Newman J, He W, Shirakawa K, Le Moan N, et al. Suppression of oxidative stress by beta-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor. Science. 2013;339:211–214. doi: 10.1126/science.1227166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luu M, Pautz S, Kohl V, Singh R, Romero R, Lucas S, et al. The short-chain fatty acid pentanoate suppresses autoimmunity by modulating the metabolic-epigenetic crosstalk in lymphocytes. Nat Commun. 2019;10:760. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08711-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vazquez-Gomez M, Garcia-Contreras C, Torres-Rovira L, Pesantez JL, Gonzalez-Anover P, Gomez-Fidalgo E, et al. Polyphenols and IUGR pregnancies: maternal hydroxytyrosol supplementation improves prenatal and early-postnatal growth and metabolism of the offspring. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu S, Tian L. Diverse phytochemicals and bioactivities in the ancient fruit and modern functional food pomegranate (Punica granatum) Molecules. 2017;22:E1606. doi: 10.3390/molecules22101606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tomas-Barberan FA, Selma MV, Espin JC. Interactions of gut microbiota with dietary polyphenols and consequences to human health. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2016;19:471–476. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Selma MV, Beltran D, Luna MC, Romo-Vaquero M, Garcia-Villalba R, Mira A, et al. Isolation of human intestinal bacteria capable of producing the bioactive metabolite isourolithin A from ellagic acid. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1521. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thakur VS, Gupta K, Gupta S. Green tea polyphenols increase p53 transcriptional activity and acetylation by suppressing class I histone deacetylases. Int J Oncol. 2012;41:353–361. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee HS, Barraza-Villarreal A, Hernandez-Vargas H, Sly PD, Biessy C, Ramakrishnan U, et al. Modulation of DNA methylation states and infant immune system by dietary supplementation with omega-3 PUFA during pregnancy in an intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:480–487. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.052241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robertson RC, Kaliannan K, Strain CR, Ross RP, Stanton C, Kang JX. Maternal omega-3 fatty acids regulate offspring obesity through persistent modulation of gut microbiota. Microbiome. 2018;6:95. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0476-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whitt J, Woo V, Lee P, Moncivaiz J, Haberman Y, Denson L, et al. Disruption of epithelial HDAC3 in intestine prevents diet-induced obesity in mice. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:501–513. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hsu CN, Hou CY, Lee CT, Chan JY, Tain YL. The interplay between maternal and post-weaning high-fat diet and gut microbiota in the developmental programming of hypertension. Nutrients. 2019;11:E1982. doi: 10.3390/nu11091982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parlee SD, MacDougald OA. Maternal nutrition and risk of obesity in offspring: the Trojan horse of developmental plasticity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:495–506. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Connor KL, Chehoud C, Altrichter A, Chan L, DeSantis TZ, Lye SJ. Maternal metabolic, immune, and microbial systems in late pregnancy vary with malnutrition in mice. Biol Reprod. 2018;98:579–592. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stanislawski MA, Dabelea D, Wagner BD, Sontag MK, Lozupone CA, Eggesbo M. Pre-pregnancy weight, gestational weight gain, and the gut microbiota of mothers and their infants. Microbiome. 2017;5:113. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0332-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vatanen T, Kostic AD, d'Hennezel E, Siljander H, Franzosa EA, Yassour M, et al. Variation in microbiome LPS immunogenicity contributes to autoimmunity in humans. Cell. 2016;165:1551. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wankhade UD, Zhong Y, Kang P, Alfaro M, Chintapalli SV, Thakali KM, et al. Enhanced offspring predisposition to steatohepatitis with maternal high-fat diet is associated with epigenetic and microbiome alterations. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soderborg TK, Clark SE, Mulligan CE, Janssen RC, Babcock L, Ir D, et al. The gut microbiota in infants of obese mothers increases inflammation and susceptibility to NAFLD. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4462. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06929-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chu DM, Antony KM, Ma J, Prince AL, Showalter L, Moller M, et al. The early infant gut microbiome varies in association with a maternal high-fat diet. Genome Med. 2016;8:77. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0330-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aagaard-Tillery KM, Grove K, Bishop J, Ke X, Fu Q, McKnight R, et al. Developmental origins of disease and determinants of chromatin structure: maternal diet modifies the primate fetal epigenome. J Mol Endocrinol. 2008;41:91–102. doi: 10.1677/JME-08-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sugino KY, Paneth N, Comstock SS. Michigan cohorts to determine associations of maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index with pregnancy and infant gastrointestinal microbial communities: late pregnancy and early infancy. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0213733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mendez-Salazar EO, Ortiz-Lopez MG, Granados-Silvestre ML, Palacios-Gonzalez B, Menjivar M. Altered gut microbiota and compositional changes in firmicutes and proteobacteria in Mexican undernourished and obese children. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2494. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Prescott SL, Wickens K, Westcott L, Jung W, Currie H, Black PN, et al. Supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus or Bifidobacterium lactis probiotics in pregnancy increases cord blood interferon-gamma and breast milk transforming growth factor-beta and immunoglobin A detection. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1606–1614. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]