Abstract

Background

Ceftolozane/tazobactam (C/T) efficacy and safety in ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is being evaluated at a double dose by several trials. This dosing is based on a pharmacokinetic (PK) model that demonstrated that 3 g q8h achieved ≥90% probability of target attainment (50% ƒT > minimal inhibitory concentration [MIC]) in plasma and epithelial lining fluid against C/T-susceptible P. aeruginosa. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of different C/T doses in patients with lower respiratory infection (LRI) due to MDR- or XDR-P. aeruginosa considering the C/T MIC.

Methods

This was a multicenter retrospective study of 90 patients with LRI caused by resistant P. aeruginosa who received a standard or high dose (HDo) of C/T. Univariable and multivariable analyses were performed to identify independent predictors of 30-day mortality.

Results

The median age (interquartile range) was 65 (51–74) years. Sixty-three (70%) patients had pneumonia, and 27 (30%) had tracheobronchitis. Thirty-three (36.7%) were ventilator-associated respiratory infections. The median C/T MIC (range) was 2 (0.5–4) mg/L. Fifty-four (60%) patients received HDo. Thirty-day mortality was 27.8% (25/90). Mortality was significantly lower in patients with P. aeruginosa strains with MIC ≤2 mg/L and receiving HDo compared with the groups with the same or higher MIC and dosage (16.2% vs 35.8%; P = .041). Multivariate analysis identified septic shock (P < .001), C/T MIC >2 mg/L (P = .045), and increasing Charlson Comorbidity Index (P = .019) as independent predictors of mortality.

Conclusions

The effectiveness of C/T in P. aeruginosa LRI was associated with an MIC ≤2 mg/L, and the lowest mortality was observed when HDo was administered for strains with C/T MIC ≤2 mg/L. HDo was not statistically associated with a better outcome.

Keywords: ceftolozane/tazobactam, multidrug-resistant, pneumonia, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, tracheobronchitis

This study evaluates the efficacy of different doses of ceftolozane/tazobactam in patients with respiratory infections due to resistant P. aeruginosa. Ceftolozane/tazobactam (C/T) effectiveness was associated with a minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) ≤2 mg/L. The lowest mortality was observed when high doses were administered for C/T MIC ≤2 mg/L strains.

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) P. aeruginosa are frequently associated with severe health care–related infections and high mortality rates [1–4]. Until recently, therapeutic options for β-lactam-resistant P. aeruginosa were limited to potentially nephrotoxic agents like colistin or aminoglycosides [5–7]. Nevertheless, the development of ceftolozane-tazobactam (C/T) offers a new option for infections caused by many of these resistant strains.

Ceftolozane is a third-generation cephalosporin with improved activity against derepressed AmpC ß-lactamase-producing P. aeruginosa, and its effectiveness is not affected by efflux pump expression or deletion of the membrane protein OprD [8]. Tazobactam is a ß-lactamase inhibitor that improves ceftolozane activity against extended-spectrum ß-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and some anaerobes. Currently, C/T is indicated for the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections (cIAIs) and urinary tract infections (cUTIs) at a dose of 1.5 g q8h [9, 10]. However, the frequency and severity of MDR- and XDR-P. aeruginosa pneumonia have led physicians to off-label use of C/T with preliminary good results [11–17], although to date there is no consensus about the proper dose considering the C/T minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) for the infecting strain.

Recently, a population pharmacokinetic (PK) model demonstrated that doubling the current Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA)–approved dose to 3 g q8h in patients with normal renal function increases the probability of target attainment (PTA) in the epithelial lining fluid (ELF) for P. aeruginosa with MICs of up to 8 mg/L, although for susceptible strains (MIC ≤ 4 mg/L), the regular dosage (1.5 g q8h) still had a 90% PTA for a 50% fT > MIC and virtually a 100% PTA for 1-log kill target (32.2% fT > MIC) [18]. The efficacy and safety of high-dose C/T are being assessed in a trial on subjects with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02070757). In the meantime, we conducted a retrospective multicenter study to evaluate the efficacy of different C/T doses in a cohort of patients with lower respiratory infection (LRI) due to MDR- or XDR-P. aeruginosa considering the C/T MIC.

METHODS

Study Design

This is a retrospective, observational study of all consecutive patients with a diagnosis of LRI (pneumonia or purulent tracheobronchitis) due to MDR- or XDR-P. aeruginosa who received treatment with C/T between 2016 and 2018. The study was conducted at 13 hospitals in 4 countries (United States, n = 6; Spain, n = 5; France, n = 1; United Kingdom, n = 1). To be eligible, patients had to have resistant P. aeruginosa isolation from at least 1 of the following samples: sputum, pleural fluid, tracheobronchial aspirate, bronchoalveolar lavage, or blood culture. Some of them have been previously published [12–14, 16, 17, 19]. The following data were recorded: age, sex, comorbidities (diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic hepatocellular disease, chronic kidney disease, hematologic and solid malignancy, cystic fibrosis), solid organ or bone marrow transplant, severity of underlying disease calculated by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), ventilator-associated infection, presence of septic shock and bacteremia, glomerular filtration, renal replacement therapy requirement, previous active antibiotherapy, days from LRI diagnosis to start of C/T, dose and duration of therapy, and concomitant active antibiotic therapy. Patients’ epidemiological and clinical data were collected from the electronic medical records of each participant hospital. Patients with any of the following criteria were excluded: (a) duration of therapy shorter than 72 hours, (b) nonavailability of MIC, or (c) documented resistance to C/T. Each investigator obtained approval from the ethics committee of the corresponding institution.

Microbiological Data

The identification of P. aeruginosa was performed according to the standard criteria of each center. P. aeruginosa was classified as MDR or XDR, as previously defined [20]. C/T susceptibility was determined by e-test [21]. The strain was classified as susceptible if the C/T MIC was ≤4 mg/L, according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST).

Definitions

All eligible patients met the clinical diagnosis of pneumonia or tracheobronchitis, as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Healthcare Safety Network. Thereby, pneumonia was identified by using a combination of imaging; clinical and laboratory criteria consisting of new and persistent infiltrate; consolidation or cavitation on chest imaging; at least 2 of the following: fever (>38.0°C), leukopenia (≤4000 white blood cell count [WBC]/mm3), or leukocytosis (>12 000 WBC/mm3); for adults >70 years old, altered mental status with no other recognized cause; at least 3 of the following: new onset of purulent sputum or change in character of sputum, increased respiratory secretions, increased suctioning requirements, new-onset or worsening cough, dyspnea, tachypnea, rales or bronchial breath sounds, or worsening gas exchange (eg, O2 desaturation, increased oxygen requirements, or increased ventilator demand); and isolation of P. aeruginosa in at least 1 sample: sputum, tracheal aspirate, broncoalveolar aspiration or bronchoalveolar lavage, pleural fluid, or blood culture. Tracheobronchial infection must include at least 1 of the following criteria: patient had no clinical or radiographic evidence of pneumonia and patient had at least 2 of the following signs or symptoms with no other recognized cause: fever (>38.0°C), cough, new or increased sputum production, rhonchi, wheezing; and at least 1 positive culture for P. aeruginosa obtained by deep tracheal aspirate or bronchoscopy on respiratory secretions [22]. Impaired renal function was defined as an estimated creatinine clearance (CrCl) ≤50 mL/min in those patients without renal replacement therapy requirement. The standard dose was considered when C/T was administered at the FDA/EMA-approved dosage for cIAI and cUTI: 1.5 g q8h for patients with a CrCl >50 mL/min; 750 mg q8h for patients with a CrCl of 30–50 mL/min; 375 mg q8h for patients with a CrCl of 15–29 mL/min; and a single loading dose of 750 mg followed by a 150-mg maintenance dose q8h for patients with end-stage renal disease or on intermittent hemodialysis. SDo for patients on continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) was 1.5 g q8h [23, 24]. High-dose was defined as the administration of double (or more) the FDA/EMA-approved dose for C/T. These means a patient with a CrCl of 30–50 mL/min who received 750 mg q8h would be included in the SDo group, whereas another patient with the same CrCl who received 1.5 g q8h would be included in the HDo group. The antibiotic dosage was selected at the discretion of the attending physician. Combination therapy was considered when another active antipseudomonal drug (aminoglycoside, colistimethate or quinolone) was given intravenously and simultaneously with C/T. Adverse events were defined as any untoward effect starting during the course of treatment that could be attributable to C/T. Clinical success was defined as resolution of clinical signs and symptoms of infection, absence of recurrence, and 30-day survival from the beginning of C/T therapy. Thirty-day mortality was considered when the patient died within 30 days after C/T onset.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was 30-day mortality. The Student t test was used to compare continuous variables. The chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to identify risk factors associated with mortality. All variables that showed significance in the univariate analysis (<.10) were included in a stepwise backward multivariate logistic regression analysis. Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 23.0). All analyses were 2-tailed, and a P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Cohort Description

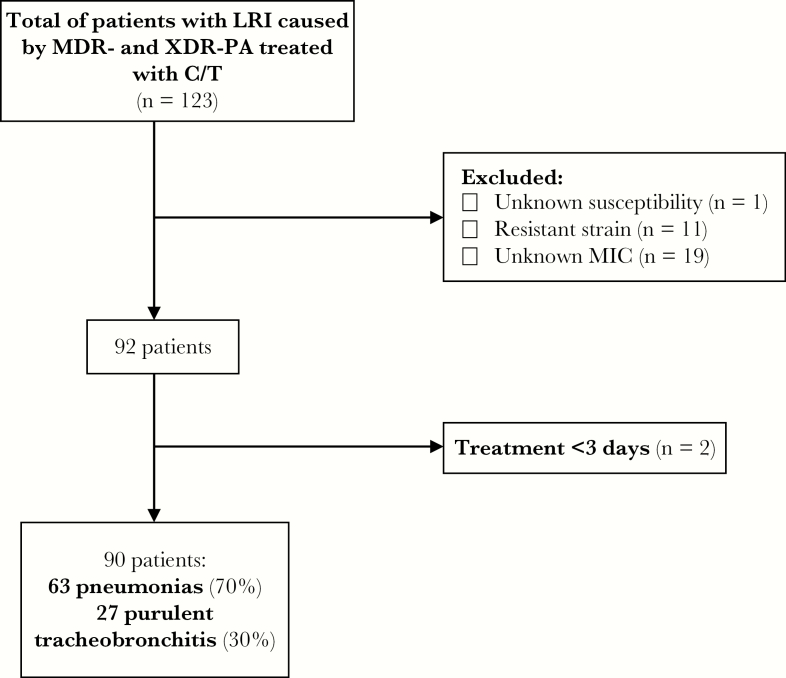

Of the 123 patients with LRI due to resistant P. aeruginosa who received treatment with C/T, 90 (73.2%) patients were eligible for the study. The flowchart of the inclusion process is shown in Figure 1. Sixty-five (72.2%) were male, and the median age (interquartile range [IQR]) was 65 (51–74) years. The main comorbidities were chronic lung disease (43.3%), vascular disease (28.9%), and diabetes (16.7%). Eight (8.9%) patients were solid organ transplant recipients (5 lung transplant). Six (6.7%) patients had cystic fibrosis. The median CCI (IQR) was 5 (2–6). The respiratory infection was pneumonia in 63 (70%) patients, of whom 4 had bacteremia and 3 empyema, and purulent tracheobronchitis in the remaining 27 (30%). In 33 (36.7%) patients, the infection was ventilator-associated and 31 (34.4%) presented with septic shock. Twenty-five (27.8%) subjects had impaired renal function, and 11 (12.2%) required CRRT.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients’ inclusion criteria. Abbreviations: C/T, ceftolozane/tazobactam; LRI, lower respiratory infection; MDR, multidrug-resistant; MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration; XDR-PA, extensively drug-resistant P. aeruginosa.

Microbiology and Treatment

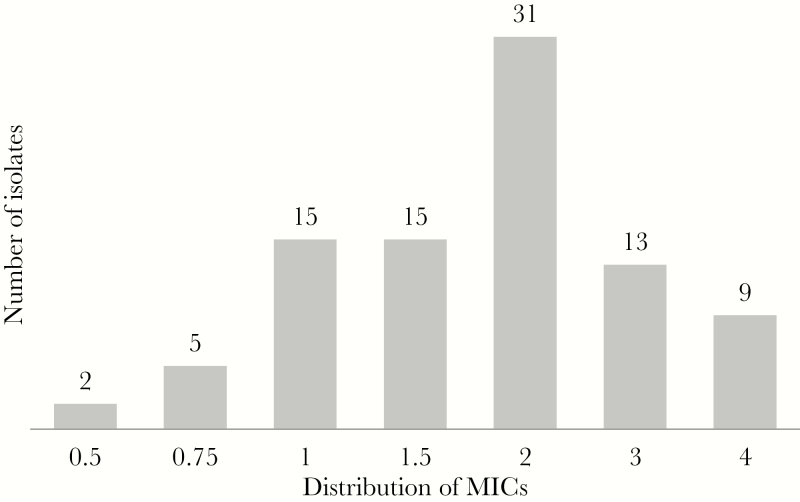

Sixty-nine (76.7%) isolates of P. aeruginosa were XDR. The median C/T MIC (range) was 2 (0.5–4) mg/L. The distribution for C/T MICs is shown in Figure 2. Thirty-six (40%) patients received SDo of C/T, and 54 (60%) received HDo according to the definition described in the “Methods” section. Thirty-seven out of 68 (54.4%) patients with an MIC ≤2 mg/L for P. aeurginosa received HDo, whereas 17 out of 22 (77.2%) patients with an MIC >2 mg/L received HDo (P = .080). In the SDo group, 77.7% (28/36) of patients had pneumonia, and in the HDo group 64.8% (35/54; P = .243). The median duration of therapy (IQR) was 14 (10–16) days. Sixty (40%) patients received concomitant intravenous and/or nebulized active antibiotics, which were intravenous colistimethate, aminoglycosides, or fluoroquinolones in 36 (40%) and nebulized colistimethate or aminoglycosides in 30 (33.3%). Follow-up samples to document eradication were obtained in 67 cases.

Figure 2.

Ceftolozane/tazobactam minimal inhibitory concentration distribution for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Abbreviation: MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration.

Outcomes and Adverse Events

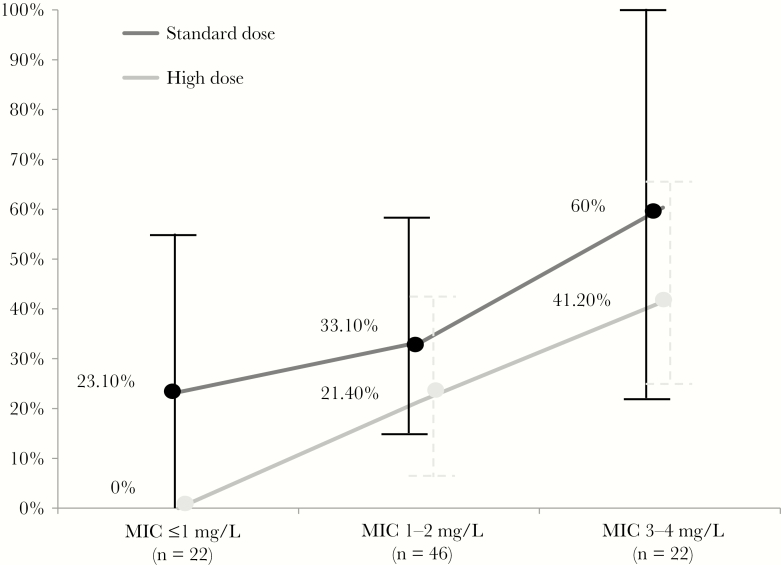

The overall 30-day mortality rate was 27.8% (25/90), 33% (21/63) in pneumonia and 14.8% (4/27) in tracheobronchitis. Clinical success was reached in 56.7% of patients (51/90). Factors associated with 30-day mortality in the univariate analysis included a high CCI (P = .029), septic shock (P < .001), and an MIC ≤2 mg/L (P = .033). A trend toward higher mortality was observed in patients with pneumonia (P = .072), ventilator-associated LRI (P = .061), and CRRT (P = .066). Renal failure, bacteremia, use of intravenous combination therapy, C/T administered within the first 48 hours of the infection diagnosis, and time to initiation of C/T or HDo were not significantly associated with 30-day mortality. For the analysis of the interaction between the MIC and C/T doses, we created a new combined variable using dichotomized MIC (≤ or >2 mg/L) and C/T dose (SDo or HDo) to describe the outcome (Table 1). Interestingly, mortality was significantly lower in those patients receiving HDo and having P. aeruginosa with a C/T MIC ≤2 mg/L than in the rest of the groups (6 out of 37, 16.2%, vs 19 out of 53, 35.8%; P = .041) and progressively increased from 29% (9 out of 31) in the MIC ≤2 mg/L and SDo group to 41.2% (7 out of 17) in the MIC >2 mg/L and HDo group, and to 60% (3 out of 5) in the MIC >2 mg/L and SDo group (Table 1). Mortality trend according to C/T dosing and MIC is shown in Figure 3. The best multivariable model predicting 30-day mortality is shown in Table 2. Factors independently associated with mortality were septic shock (P < .001), C/T MIC >2 mg/L (P = .045), and increasing CCI (P = .037).

Table 1.

Univariate Analysis of Factors Associated With 30-Day Mortality in the 90 Patients With MDR- and XDR-Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lower Respiratory Tract Infection

| Variable | Survivors (n = 65) | Nonsurvivors (n = 25) | P Value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 48 (73.8) | 17 (68) | .579 | 1.3 (0.5–3.6) |

| Age (SD), y | 61 (18.8) | 63 (13.5) | .626 | 1 (0.9–1) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | 11 (16.9) | 4 (16) | 1 | 0.9 (0.9–3.2) |

| Chronic renal failure | 11 (16.9) | 2 (8) | .503 | 0.4 (0.1–2.1) |

| Vascular disease | 17 (26.2) | 9 (36) | .356 | 1.6 (0.6–4.3) |

| Cirrhosis | 3 (4.6) | 1 (4) | 1 | 0.9 (0.1–8.7) |

| Asthma/COPD | 28 (43.1) | 11 (44) | .937 | 1 (0.4–2.6) |

| Cystic fibrosis | 6 (9.2) | 0 | .181 | - |

| Solid cancer | 9 (13.8) | 4 (16) | .749 | 1.2 (0.3–4.3) |

| Hematological cancer | 3 (4.6) | 1 (4) | 1 | 0.9 (0.9–8.7) |

| Solid organ transplant recipient | 6 (9.2) | 2 (8) | 1 | 0.9 (0.2–4.5) |

| Charlson index score (SD) | 4.2 (2.6) | 5.56 (2.8) | .029 | 1.2 (1–1.4) |

| Pneumonia | 42 (64.6) | 21 (84) | .072 | 2.9 (0.9–9.4) |

| Ventilator-associated infection | 20 (30.8) | 13 (52) | .061 | 2.4 (0.9–6.3) |

| Bacteremia | 3 (4.6) | 1 (4) | .899 | 0.9 (0.9–8.7) |

| Septic shock | 15 (23.1) | 16 (64) | <.001 | 5.9 (2.2–16.1) |

| Glomerular filtration ≤50 mL/min | 19 (29.2) | 6 (24) | .620 | 0.8 (0.3–2.2) |

| CRRT | 5 (7.7) | 6 (24) | .066 | 3.8 (1–13.8) |

| XDR | 48 (73.8) | 21 (84) | .308 | 1.9 (0.6–6.2) |

| MIC ≤ 2 mg/L | 53 (81.5) | 15 (60) | .033 | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) |

| MIC (SD), mg/L | 1.8 (0.9) | 2.4 (1.1) | .019 | 1.8 (1.1–3) |

| HDo | 41 (63.1) | 13 (52) | .349 | 0.6 (0.3–1.6) |

| C/T MIC and dose interaction | ||||

| MIC ≤ 2 mg/L + HDo | 31 (47.7) | 6 (24) | .041 | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) |

| MIC ≤ 2 mg/L + SDo | 22 (33.8) | 9 (36) | .847 | 1.1 (0.4–2.9) |

| MIC > 2 mg/L + HDo | 10 (15.4) | 7 (28) | .229 | 2.1 (0.7–6.4) |

| MIC > 2 mg/L + SDo | 2 (3.1) | 3 (12) | .129 | 4.3 (0.7–27.4) |

| C/T within 48 h (55 out of 78)a | 32 (58.2) | 13 (56.5) | 1 | 0.9 (0.4–2.5) |

| Previous active antibiotherapy (33 out of 78)b | 11 (47.8) | 8 (80) | .131 | 1.8 (0.8–2.2) |

| Mean time to C/T (SD), da | 3.6 (5.7) | 3.7 (5.8) | .971 | 1 (0.9–1.1) |

| Mean duration of C/T (SD), d | 14 (5.8) | 12.8 (5.8) | .363 | 0.9 (0.8–1) |

| Concomitant intravenous treatment | 23 (35.4) | 13 (52) | .150 | 2 (0.8–5) |

| Adverse reactions | 3 (4.6) | 1 (4) | 1 | 1.2 (0.1–11.7) |

Abbreviations: C/T, ceftolozane/tazobactam; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; HDo, pharmacokinetics-based dose; MDR, multidrug-resistant; MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration; OR, odds ratio; SDo, standard dose; XDR, extensively drug-resistant.

aWithin the first 48 hours after P.aeruginosa was isolated. This information was available in 78 cases.

bInformation available in 78 cases. The 45 cases where C/T was the initial antibiotic were also excluded.

Figure 3.

Thirty-day mortality rates according to ceftolozane/tazobactam dosing and minimal inhibitory concentration. Abbreviation: MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration.

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated With 30-Day Mortality in the 90 Patients With MDR- and XDR-Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lower Respiratory Tract Infections

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Septic shock | 7.96 | 2.59–24.54 | <.0001 |

| C/T MIC > 2 mg/L | 3.33 | 1.02–10.86 | .045 |

| Charlson index score | 1.27 | 1.04–1.55 | .019 |

Abbreviations: C/T, ceftolozane/tazobactam; CI, confidence interval; MDR, multidrug-resistant; MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration; OR, odds ratio; XDR, extensively drug-resistant.

Four episodes of adverse reactions were attributable to C/T: leukopenia, encephalopathy plus myoclonus, renal failure, and hepatitis.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the largest cohort study evaluating the outcome of patients with LRI due to MDR- and XDR-P. aeruginosa treated with C/T. The overall 30-day mortality rate was 27.8% (25/90), and 33% (21/63) for patients with pneumonia. These figures were lower than the 40%–50% previously reported in patients with pneumonia due to resistant and nonresistant P. aeruginosa treated with other antibiotics [1–4]. In recent retrospective studies of patients with resistant P. aeruginosa infections who received C/T, 30- and 90-day mortality rates for LRI ranged between 11% (2/18) and 33% (2/6) [14, 15, 17] and 21% (3/14) [13], respectively. Despite the small size, retrospective nature, and potential indication bias in these studies, the low mortality rate is noteworthy, particularly in a cohort like ours, characterized by a median age of 65 years, a median CCI of 5, and the presence of septic shock in 34% of the cases.

C/T current approved dosage is 1.5 g q8h, and a population pharmacokinetic model indicated that this exposure had a ≥90% probability of attaining a 50% ƒT > MIC target in plasma and ELF against P. aeruginosa with an MIC of up to 4 mg/L (EUCAST breakpoint) [18]. However, SDo was far from achieving the 50% ƒT > MIC ELF target for strains with MICs of up to 8 mg/L (59% PTA), which only could be approached with HDo (87.7% PTA). Even if in Europe, a strain with an MIC of 8 mg/L would be considered resistant, and hence the use of C/T strongly discouraged. Clinicians may still consider it more reliable to resort to high-dose C/T when treating patients with pneumonia due to C/T-susceptible P. aeruginosa because in about 25% of cases the MIC may be higher than 2 mg/L, and therefore anywhere within a double dilution of the actually measured 3–4 mg/L MIC value. Although there are no clinical data supporting the use of higher doses of C/T considering the MIC value [11–17], 2 studies showed a relationship between clinical failure and a higher MIC [13, 17].

To investigate these questions, we analyzed 90 patients treated with C/T. The main finding was the association of an increasing MIC with mortality. A relative 82% increase in mortality per each point of increment in MIC was noted after adjusting for the most relevant prognostic factors (septic shock and CCI) (Table 2). We also noted what seems to be an influence of dosage on mortality, as is shown in Figure 3 by the rather parallel disposition of the SDo and HDo lines. However, the 12%–20% greater 30-day mortality between patients receiving SDo and HDo observed across the entire MIC range did not reach statistical significance. Indeed, the lowest mortality rate was observed in those patients receiving HDo when the C/T MIC was ≤2 mg/L (16%), supporting the recommendation of HDo for patients with P. aeruginosa LRI. On the other hand, even using HDo, the mortality rate when the C/T MIC was >2 mg/L was high (Figure 3). These results agree with a recent study in which the authors evaluated the outcome of P. aeruginosa bacteremia treated with cefepime and observed that the use of a high dose (2 g q8h) did not improve the outcome when the MIC was >2 mg/L [25]. We cannot provide a definitive explanation of the relationship between increasing MIC and mortality. In the neutropenic mouse infection model, the MIC value does not affect the microbiological response when the appropriate %fT > MIC is attained [26]. Obviously, an increase in MIC will diminish the magnitude of any PK-PD parameter, including the fT > MIC. However, for MICs ≤1 mg/L, a 100% PTA in ELF for the 50% fT > MIC target is expected with SDo, and we still found a 23% greater mortality in patients infected with these strains when treated with SDo vs HDo. The majority of animal models have demonstrated that fT > MIC values of ≥60%–70% for cephalosporins, ≥50% for penicillins, and ≥40% for carbapenems provide maximal bactericidal effect [27]. However, some clinical studies have indicated that a 100% fT > MIC for ceftazidime and cefepime, or even a 95% 4.3*T > MIC for cefepime, is necessary for optimal response in patients with infections due to gram-negative bacilli [28, 29]. In the neutropenic mouse infection model, P. aeruginosa T > MIC targets for C/T in plasma are lower than for other cephalosporins and similar to those for carbapenems (about 40% fT > MIC for maximal bactericidal activity) [26, 30]. However, even for carbapenenems, more stringent PK-PD targets have been associated with improved clinical or microbiological response in febrile neutropenic patients with bacteremia (>75% T > MIC) and patients with LRI (fCmin/MIC > 5) [31, 32]. Aditionally, MICs > 2 mg/L may reflect the presence of first-step (low-level) resistance mechanisms (such as AmpC overexpression) that could favor the emergence of high-level (clinical) resistance (such as mutations leading to the structural modification of AmpC) leading to treatment failure [33]. In any case, we encourage the use of HDo in all patients with MDR-P. aeruginosa, as well as additional actions when MIC >2 mg/L. In the latter circumstance, administration of C/T as an extended or continuous infusion and/or in combination with other active agents may be worth considering [34].

On the other hand, selection of C/T-resistant mutants was evaluated in a hollow-fiber infection model that exposed 2 strains of P. aeruginosa with C/T MICs of 0.5 and 4 mg/L to a range of C/T doses [35]. No resistant mutant was selected for the low-MIC strains, but only the 3 g q8h simulated dosage avoided the emergence of resistance from the strain with an MIC of 4 mg/L. This hollow-fiber model simulated the plasma concentrations but not the concentration achieved in the ELF, respiratory secretions, cerebrospinal fluid, or abscesses. This may explain why in the clinical setting the HDo may not be enough to prevent resistance.

It is of note that neither in our series nor in others was combination of C/T with other antibiotics associated with an improved outcome or prevention of resistance emergence. However, the most common companion drugs were aminoglycosides or colistin, which are frequently underdosed and may have low diffusion to some tissues. It is necessary to prospectively evaluate the effect of combining C/T with correctly dosed aminoglycosides, colistin, or even meropenem in severe infections with a high bacterial inoculum [36–38].

Our study has some limitations. First, its retrospective nature and the relatively small size of the cohort preclude a generalization of the results; however, this is the largest cohort of LRI due to resistant P. aeruginosa treated with C/T. Second, the C/T dose was not standardized but was decided by each physician; therefore, neither the reason for receiving SDo or HDo nor the dose adjustment in case of renal failure was well defined. Nevertheless, this variability allowed us to analyze the impact of different regimens. Third, we did not assess clinical failure due to the inherent difficulties for evaluating it retrospectively and chose 30-day mortality as the most objective evaluable outcome. Finally, subsequent strains of P. aeruginosa isolated after starting C/T were not available; hence, documentation of persistence (microbiological failure) and emergence of resistance could not be assessed.

In conclusion, this study indicates that C/T is a valuable option for treating LRI caused by resistant P. aeruginosa. However, the effectiveness was associated with lower MICs and to a lesser extent with higher dosage; hence, the lowest mortality (16%) was observed when the HDo was administered for treating strains with MIC ≤2 mg/L. A randomized controlled trial is required to confirm these findings. For higher MICs (up to 4 mg/L), further actions aimed at improving prognosis, such as the administration of C/T as an extended or continuous infusion or in combination with other active antibiotics, also deserve clinical testing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marc Xipell, MD, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Solen Kernéis, MD, University Hospital of Paris, Sandrine Henard, MD, University Hospital of Nancy, Benjamin Wyplosz, MD, University Hospital of Paris, David Lebeaux, MD, University Hospital of Paris, Tristan Ferry, MD, University Hospital of Lyon, and Guillaume Béraud, MD, University Hospital of Poitiers, for their help with data collection. This work was supported by REIPI (Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases) (This study was neither financed nor carried out by the REIPI).

Financial support. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Potential conflicts of interest. A.S. and A.O. have received fees as speakers for MSD; O.G. has received fees as a speaker for Pfizer; C.J.J. and X.N. have received fees as speakers for MSD & Pfizer. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Tumbarello M, De Pascale G, Trecarichi EM, et al. . Clinical outcomes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39:682–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peña C, Gómez-Zorrilla S, Oriol I, et al. . Impact of multidrug resistance on Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia outcome: predictors of early and crude mortality. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; 32:413–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Combes A, Luyt CE, Fagon JY, et al. . Impact of piperacillin resistance on the outcome of Pseudomonas ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med 2006; 32:1970–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Micek ST, Wunderink RG, Kollef MH, et al. . An international multicenter retrospective study of Pseudomonas aeruginosa nosocomial pneumonia: impact of multidrug resistance. Crit Care 2015; 19:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Akajagbor DS, Wilson SL, Shere-Wolfe KD, et al. . Higher incidence of acute kidney injury with intravenous colistimethate sodium compared with polymyxin B in critically ill patients at a tertiary care medical center. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:1300–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oliveira JF, Silva CA, Barbieri CD, et al. . Prevalence and risk factors for aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity in intensive care units. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:2887–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sader HS, Farrell DJ, Flamm RK, Jones RN. Antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-negative organisms isolated from patients hospitalised with pneumonia in US and European hospitals: results from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Suerveillance Program, 2009–2012). Int J Antimicrob Agents 2014; 43:328–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moyá B, Zamorano L, Juan C, et al. . Activity of a new cephalosporin, CXA-101 (FR264205), against beta-lactam-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants selected in vitro and after antipseudomonal treatment of intensive care unit patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54:1213–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Solomkin J, Hershberger E, Miller B, et al. . Ceftolozane/tazobactam plus metronidazole for complicated intra-abdominal infections in an era of multidrug resistance: results from a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial (ASPECT-cIAI). Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1462–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huntington JA, Sakoulas G, Umeh O, et al. . Efficacy of ceftolozane/tazobactam versus levofloxacin in the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections (cUTIs) caused by levofloxacin-resistant pathogens: results from the ASPECT-cUTI trial. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 71:2014–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gelfand MS, Cleveland KO. Ceftolozane/tazobactam therapy of respiratory infections due to multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:853–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xipell M, Paredes S, Fresco L, et al. . Clinical experience with ceftolozane/tazobactam in patients with serious infections due to resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2018; 13:165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Escolà-Vergé L, Pigrau C, Los-Arcos I et al. . Ceftolozane/tazobactam for the treatment of XDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Infection 2018; 46:461–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Castón JJ, De la Torre A, Ruiz-Camps I, et al. . Salvage therapy with ceftolozane-tazobactam for multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haidar G, Philips NJ, Shields RK, et al. . Ceftolozane-tazobactam for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: clinical effectiveness and evolution of resistance. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:110–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Munita JM, Aitken SL, Miller WR, et al. . Multicenter evaluation of ceftolozane/tazobactam for serious infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:158–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Díaz-Cañestro M, Periañez L, Mulet X et al. . Ceftolozane/tazobactam for the treatment of multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: experience from the Balearic Islands. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2018; 37:2191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xiao AJ, Miller BW, Huntington JA, Nicolau DP. Ceftolozane/tazobactam pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic-derived dose justification for phase 3 studies in patients with nosocomial pneumonia. J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 56:56–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dinh A, Wyplosz B, Kernéis S, et al. . Use of ceftolozane/tazobactam as salvage therapy for infections due to extensively drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2017; 49:782–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, et al. . Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18:268–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bailey AL, Armstrong T, Hari-Prakash D, et al. . Multicenter evaluation of the etest gradient diffusion method for ceftolozane-tazobactam susceptibility testing of Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol. 2018; 27:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control 2008; 36:309–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bremmer DN, Nicolau DP, Burcham P, et al. . Ceftolozane/tazobactam pharmacokinetics in a critically ill adult receiving continuous renal replacement therapy. Pharmacotherapy 2016; 36:e30–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oliver WD, Heil EL, Gonzales JP, et al. . Ceftolozane-tazobactam pharmacokinetics in a critically Ill patient on continuous venovenous hemofiltration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 60:1899–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Su TY, Ye JJ, Yang CC, et al. . Influence of borderline cefepime MIC on the outcome of cefepime-susceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia treated with a maximal cefepime dose: a hospital-based retrospective study. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2017; 16:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lepak AJ, Reda A, Marchillo K, et al. . Impact of MIC range for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Streptococcus pneumoniae on the ceftolozane in vivo pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic target. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:6311–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Craig WA. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 26:1–10; quiz 11–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McKinnon PS, Paladino JA, Schentag JJ. Evaluation of area under the inhibitory curve (AUIC) and time above the minimum inhibitory concentration (T>MIC) as predictors of outcome for cefepime and ceftazidime in serious bacterial infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2008; 31:345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tam VH, McKinnon PS, Akins RL, et al. . Pharmacodynamics of cefepime in patients with gram-negative infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 2002; 50:425–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Craig WA, Andes DR. In vivo activities of ceftolozane, a new cephalosporin, with and without tazobactam against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae, including strains with extended-spectrum β-lactamases, in the thighs of neutropenic mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57:1577–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ariano RE, Nyhlén A, Donnelly JP, et al. . Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of meropenem in febrile neutropenic patients with bacteremia. Ann Pharmacother 2005; 39:32–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li C, Du X, Kuti JL, Nicolau DP. Clinical pharmacodynamics of meropenem in patients with lower respiratory tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007; 51:1725–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fraile-Ribot PA, Cabot G, Mulet X et al. . Mechanisms leading to in vivo ceftolozane/tazobactam resistant development during the treatment of infections caused by MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017; 73:658–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Terracciano J, Rhee EG, Walsh J. Chemical stability of ceftolozane/tazobactam in polyvinylchloride bags and elastomeric pumps. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 2017; 84:22–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. VanScoy BD, Mendes RE, Castanheira M, et al. . Relationship between ceftolozane-tazobactam exposure and selection for Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistance in a hollow-fiber infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:6024–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rico-Caballero V, Almarzoky Abuhussain S, Kuti JL, Nicolau DP. Efficacy of human-simulated exposures of ceftolozane-tazobactam alone and in combination with amikacin of colistin against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Noel AR, Bowker KE, Attwood M, MacGowan AP. Antibacterial effect of ceftolozane/tazobactam in combination with amikacin against aerobic gram-negative bacilli studied in an in vitro pharmacokinetic model of infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73:2411–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Montero M, VanScoy BD, López-Causapé C et al. . Evaluation of ceftolozane-tazobactam in combination with meropenem against Pseudomonas aeruginosa sequence type 175 in a hollow-fiber infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]