Abstract

Waiting impulsivity is a risk factor for many psychiatric disorders including alcohol use disorder (AUD). Highly impulsive individuals are vulnerable to alcohol abuse. However, it is not well understood whether chronic alcohol use increases the propensity for impulsive behavior. Here, we establish a novel experimental paradigm demonstrating that continuous binge-like ethanol exposure progressively leads to maladaptive impulsive behavior. To test waiting impulsivity, we employed the 5-choice serial reaction time task (5-CSRTT) in C57BL/6J male mice. We assessed premature responses in the fixed and variable inter-trial interval (ITI) 5-CSRTT sessions. We further characterized our ethanol-induced impulsive mice using Open Field, y-maze, 2-bottle choice, and an action-outcome task. Our results indicate that continuous binge-like ethanol exposure significantly increased premature responses when mice were tested in variable ITI sessions even during a prolonged abstinent period. Ethanol-induced impulsive mice exhibited anxiety-like behavior during chronic exposures. This behavior was also observed in a separate cohort that was subjected to twenty days of abstinence. Ethanol-treated mice were less motivated for a sucrose reward compared to air-exposed control mice, while also demonstrating reduced responding during action-outcome testing. Overall, ethanol-treated mice demonstrated increased impulsive behavior, but a reduced motivation for a sucrose reward. Although waiting impulsivity has been hypothesized to be a trait or risk factor for AUD, our findings indicate that maladaptive impulse control can also be potentiated or induced by continuous chronic ethanol exposure in mice.

Keywords: Alcohol, Motivation, AUD, Impulsivity, Operant

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a prevalent and highly disabling disorder, associated with many physical and psychiatric comorbidities (Grant et al., 2015; Rehm et al., 2014; Wittchen et al., 2011). A major feature of AUD is the culmination of excessive drinking resulting in withdrawal symptoms upon cessation of alcohol consumption (Association, 2013; Day et al., 2015). Several medications have been approved for the treatment of AUD, but only a fraction of patients respond to the treatment (Bouza et al., 2004; Rosner et al., 2008). Prevention of AUD has proven challenging, but several risk factors have been identified. Impulsivity is known as an inherent trait and an important risk factor associated with AUD and other addictive behaviors. (Crews and Boettiger, 2009; Ginley et al., 2014; Jakubczyk et al., 2013). Impulsivity is a multifaceted, measurable phenomenon, commonly described as acting with little or no forethought (Bari and Robbins, 2013; Jentsch et al., 2014). Substantial experimental evidence suggests that impulsivity contributes to the development of substance use disorder and AUD and impacts the progression of these disorders (de Wit, 2009; Koob and Volkow, 2010). For instance, maladaptive impulsive behavior has been shown to increase the likelihood of binge alcohol drinking, aggression, and even suicide (Kreek et al., 2005).Cumulatively, more studies are demonstrating that impulsivity is strongly correlated with binge alcohol drinking in AUD patients (Westman et al., 2017; Yarmush et al., 2016). However, if binge alcohol drinking induces or exacerbates innate impulsivity has yet to be thoroughly investigated.

AUD has a wide range of disease comorbidities, such as depression and anxiety, that can decrease the quality of life and increase the risk of suicide (Oliveira et al., 2018; Saha et al., 2018; Samokhvalov et al., 2018). One such comorbidity is anhedonia, the decreased ability or inability to feel pleasure, which usually coincides with symptoms of depression and has been heavily evaluated in rodent models (Liu et al., 2018). Furthermore, decreased motivation for sucrose rewards has been shown in rats after prolonged ethanol exposure schedules suggesting a developed anhedonic response to a once desired natural reward (Slawecki, 2006). Thus, ethanol may have an inherent dampening on reward-seeking. Additionally, AUD patients suffer from a preoccupation with alcohol and habitual consumption leading to repetitive alcohol-seeking behavior (O’Tousa and Grahame, 2014). Lastly, binge drinking has been shown to induce neurodegeneration in various ways, such as changes in neuroimmune signaling and the loss of myelination (Crews and Vetreno, 2014; Harper, 2009). Indeed, binge or chronic ethanol exposure is known to dampen cognitive function (Coleman et al., 2014; Crews et al., 2017; Vetreno et al., 2017). Due to the aforementioned disorders, prevention of AUD development is of critical importance.

Trait impulsivity is a major concern when predicting future alcohol or substance abuse. Thus, it is of great importance that we begin to understand the role alcohol may play in promoting impulsive behavior for a natural reward. In chronic intermittent ethanol (CIE) exposure models, ethanol consumption increases in CIE mice if they had learned to consume ethanol prior to treatment (Becker and Lopez, 2004). Thus, in this study, we present a novel ethanol treatment schedule intended to model binge-like exposure by utilizing short durations within ethanol vapor. Concurrently, we utilized the 5-CSRTT to model relevant human waiting impulsivity in mice while they faced their ethanol treatment schedule (Robbins, 2002). This paradigm displays humanistic challenges of waiting impulsivity in the face of chronic binge-like ethanol exposures. Consequently, after a period of abstinence from ethanol exposures, we assessed ethanol consumption and preference in our paradigm. Further, we explored the effect of ethanol-induced impulsivity on goal-directed behavior to investigate the risk of binge-like ethanol exposure to the formation of habitual behavior. Using our model, we hypothesized that ethanol-exposed mice will exhibit increased impulsivity, decreased sucrose seeking, and anxiety-like behavior compared to air-exposed mice. Our approach demonstrated that daily binge alcohol exposure promotes maladaptive impulsive behavior as well as a decrease in motivation for a natural reward.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories Inc. Mice were group housed in standard Plexiglas cages with ad libitum access to food and water until food restriction began at eight weeks of age. Mice were maintained on a 12h:12h light and dark cycle. Animal care and handling procedures were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees in accordance with NIH guidelines.

5-Choice Serial Reaction Time Task (5-CSRTT)

A detailed description of the experimental training and ethanol treatment schedule is described in the supplementary methods. Importantly, for the “continuous cohort”, mice received ethanol treatments every day even through impulsivity testing. For the “abstinent cohort”, ethanol treatments were stopped three days prior to their first impulsivity test.

Action-Outcome Test

Goal-directed and sucrose seeking behavior was observed using s 2-hole operant chamber (MED-307A-B2, Med-Associates). A detailed description of the test is outlined within the Supplementary Methods.

Open Field Test, Spontaneous Alternation, Blood Ethanol Content, and Drinking Behavior

Locomotor activity and working memory were measured by using the Open Field and y-maze, respectively. Ethanol consumption and preference were determined using a 2-bottle choice protocol. Plasma blood ethanol concentration (BEC) was measured using the Analox AM1 system. Detailed procedures are described in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Statistical Analysis

5-CSRTT and ethanol drinking testing were analyzed by two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, where appropriate. All ANOVAs where a main effect is reported without being followed with an interaction represent comparisons where the interaction was non-significant. Student’s t-tests were used for comparison of fixed ITI impulsivity test to variable impulsivity test of AE and EE mice. A two-way ANOVA was used to compare AE and EE fixed and variable impulsivity testing. Fixed and variable impulsivity testing was calculated by averaging three days for each session type. Anxiety-like behavior and spontaneous alternation was analyzed by using a student’s t-test. Sucrose-seeking behavior was analyzed by two-way repeated measures ANOVA, with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons tests, for CSF and RI data. A two-way ANOVA was used for comparing valued and devalued sessions between AE and EE mice. Student’s t-tests were used for comparison of trough latency, time spent in the trough, and tone trough latency. Linear regression analysis was utilized for the comparison of sucrose-seeking behavior to premature responding. All statistical analysis was calculated using Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

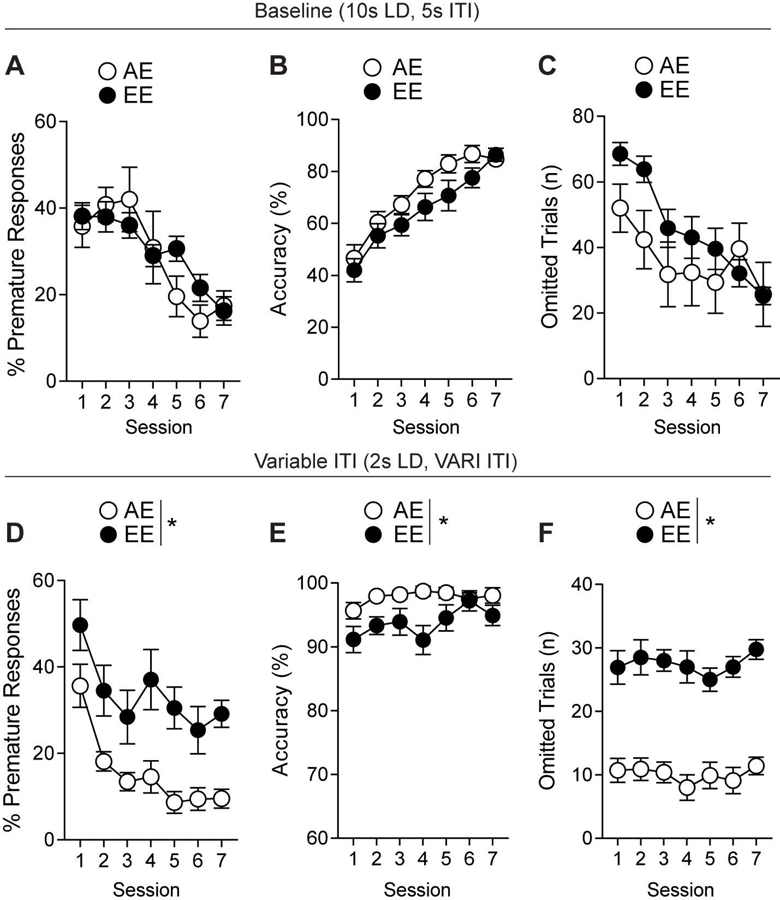

Daily Ethanol Exposure Induces Maladaptive Waiting Impulsivity

To examine chronic binge ethanol exposure, we subjected our “continuous cohort” of mice to daily four hour ethanol vapor exposures. Baseline, AE (n=9) and EE (n=12) mice prior to ethanol treatment, testing showed no differences in premature responses (F1,20=0.039, p=0.846, Fig. 1A), with a main effect on session (F6,120=10.94, p<0.01, Fig. 1A). Both groups displayed similar accuracy in the task (F1,19=1.959, p=0.178, Fig. 1B), with a main effect seen on session (F6,120=23.5, p<0.01, Fig. 1B). Baseline omissions showed no difference between groups (F1,20=0.424, p=0.523, Fig. 1C) and had a main effect on session (F6,120=25.76, p<0.01, Fig. 1C), an interaction was seen between groups and time (F6,120=3.756, p=0.002, Fig. 1C), post-hoc analysis revealed no time points to be significant. During variable ITI impulsivity testing, EE mice displayed increased premature responding (F1,20=12.67, p<0.01, Fig. 1D) with the main effect on session (F6,120=12.7, p<0.01). These mice also displayed decreased overall accuracy (F1,20=7.585, p<0.01, Fig. 1E) and higher omission rates (F1,20=58.21, p<0.01, Fig. 1F) compared to AE mice. EE mice showed a significant decrease in perseverative responding (F1,20=5.309, p=0.032, Fig. S2A). No differences in magazine entries (F1,20=0.557, p=0.464, Fig. S2B) between the groups was observed, but a main effect on session was present (F6,120=3.76, p=002, Fig. 2B). No differences were observed in reward latency (F1,20=1.507, p=0.234, Fig. S2C). Without correcting for omissions, both groups displayed similar levels of premature responses (F1,20=13.4, p=0.08, Fig. S5A). However, day to day comparison shows significant differences on the fifth [t(18)=2.925, p<0.01, Fig. S5B] and seventh days [t(18)=2.435, p=0.025, Fig. S5B] of impulsivity testing. Lastly, we found that there was no significant difference in overall nosepoke activity between the groups during the variable sessions [t(12)=2.036, p=0.06, Fig. S5C]

Figure 1.

Continuous ethanol vapor treatments increase impulsive responding in mice. (a) Pre-treatment baseline testing for showing no differences in percent premature responses, (b) accuracy, (c) or omitted trials. (d) Variable ITI impulsivity testing revealed differences in percent premature responses, (e) accuracy, and (f) omitted trials. n=8–10/group. *p<0.05 for effect of treatment. All data are expressed as ± s.e.m.

Figure 2.

Ethanol-induced impulsivity remains during abstinence. (a) Pre-treatment baseline testing for percent premature trials, (b) accuracy, (c) and omitted trials. (d) mice showed differences in percent premature, (e) accuracy, and (f) omitted trials during impulsivity testing through treatment abstinence. *p<0.05 for effect of treatment. n= 9–12/group. All data are expressed as ± s.e.m.

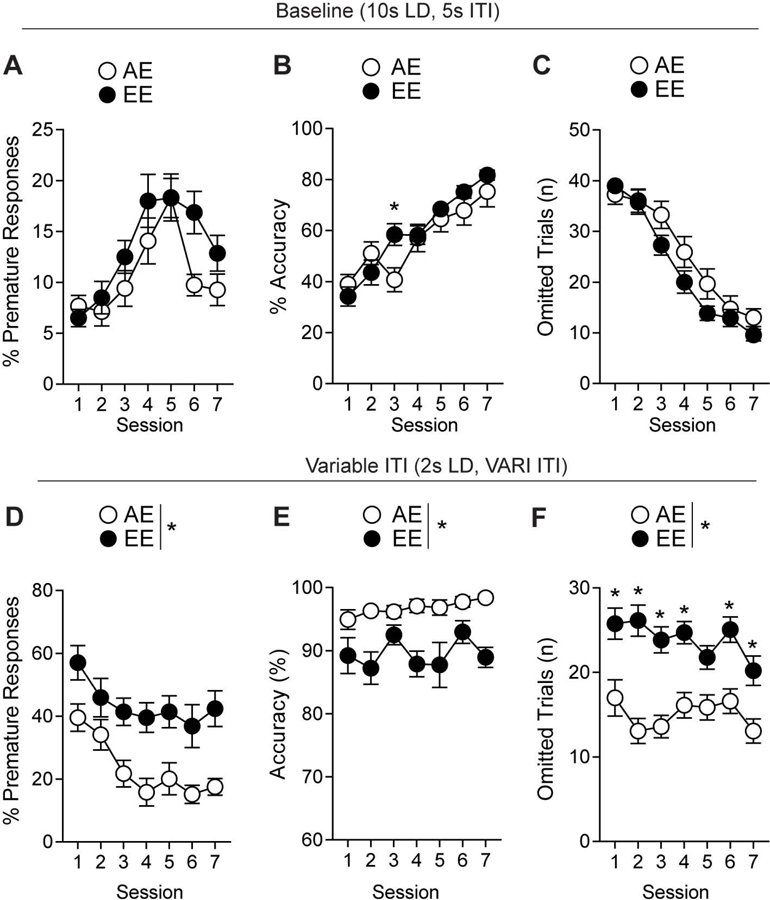

Maladaptive Waiting Impulsivity Persists After Cessation of Ethanol Exposures

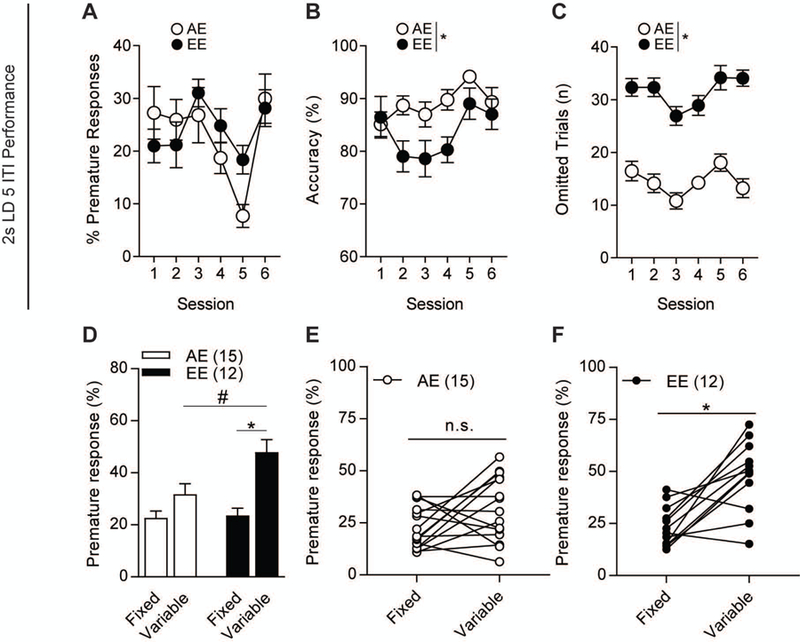

In order to distinguish acute withdrawal behavior from lasting neurobehavioral changes, we sought to eliminate ethanol treatment in our experimental schedule to show maladaptive impulsivity through chronic withdrawal. A separate “abstinent cohort” of mice was subjected to the experimental paradigm previously described (Fig. S1A-D). AE (n=15) and EE (n=12) mice displayed no differences in baseline premature responses (F1,25=3.91, p=0.059, Fig. 2A), with a main effect over sessions (F6,150=14.43, p<0.01). Groups displayed similar accuracy (F1,25=0.046, p=0.83, Fig. 2B) and improved over subsequent sessions (F6,150=39.06, p<0.01, Fig. 2B). An interaction between groups and session was seen on accuracy during baseline (F6,150=2.239, p=0.043, Fig. 2B), with post-hoc analysis showing significance on the third day. Omissions remained similar (F1,25=1.823, p=189, Fig. 2C) between groups while also improving over sessions (F6,150=111.1, p<0.01, Fig. 2C). An interaction was observed between groups and session (F6,150=2.613, p=0.019, Fig. 2C) for omissions, but no significance was found in the post-hoc analysis. Ethanol treatments ended three days prior to the first variable ITI session to observe impulsivity during abstinence. We observed similar results as the previous cohort with increased premature responding (F1,25=12.55, p<0.01, Fig. 2D) and a main effect over sessions (F6,150=10.96, p<0.01, Fig. 2D). The overall accuracy decreased significantly in the EE mice compared to AE mice (F1,25=21.98, p<0.01, Fig. 2E). These mice also had significantly higher omissions during impulsivity testing (F1,25=22.65, p<0.01, Fig. 2F). An interaction between groups and session was seen in increased omissions of the EE mice (F1,150=2.535, p<0.023, Fig. 2F), with the fifth day being the only non-significant day as determined by post-hoc analysis . Without correcting for omissions, EE mice displayed significantly higher premature nosepoking than AE mice (F1,25=7.573, p=0.011, Fig. S5D). Separately, the second, third, fifth, sixth, and seventh days displayed increased premature nosepoking in the EE mice [t(25)=2.075, p=0.048, t(25)=2.642, p=0.014, t(25)=2.149, p=0.041, t(25)=2.928, p<0.01, t(25)=2.817, p<0.01, respectively, Fig. S5E]. Additionally, there was no difference seen in overall nosepoking behavior [t(25)=0.115, p=0.91, Fig. S5F).Further, unlike the “continuous cohort”, the “abstinent cohort” displayed no differences in perseverative responses (F1,25=0.303, p=0.587, Fig. S2D) and magazine entries between the groups (F1,25=0.442, p=0.512, Fig. S2E). A significant increase in reward latency (F1,25=11.66, p<0.01, Fig. S2F) was observed. The differences in premature responding were not seen in the final stage of fixed ITI training (2s LD, 5s ITI, F1,25=22.65, p<0.01, Fig. 3A), with only a main effect over sessions (F5,110=6.359, p<0.01, Fig. 3A). A significant difference in overall accuracy was found (F1,25=22.65, p<0.01, Fig. 3B) between groups and a main effect was observed over sessions (F6,125=4.511, p<0.01, Fig. 3B). The EE mice were also displaying increased omissions during fixed ITI training with the main effect on groups (F1,25=22.65, p<0.01, Fig. 3C) and over the sessions (F5,125=8.158, p<0.01, Fig. 3C). In order to fully visualize the impact of ethanol treatment on impulsive behavior, we compared the impulsivity baseline test (7s ITI) prior to treatments with their variable ITI testing post-treatments. Mice were separated into groups evenly based on percentage of premature responses of the baseline impulsivity test [t(25)=0.247, p=0.807, Fig. 3D]. There was no significant difference between AE mice performance comparing their fixed and variable testing [t(14)=1.832, p=0.09, Fig. 3E]. However, the EE mice displayed a significant increase in the change in impulsiveness [t(11)=4.294, p<0.01, Fig. 3F] when comparing their baseline impulsivity test and main impulsivity test.

Figure 3.

Fixed baseline impulsivity testing comparison to variable ITI impulsivity testing. 2s LD, 5s ITI performance shows no differences in (a) percent premature responses. (b) Overall accuracy and (c) omitted trials were significantly different between groups. (d) Percent premature responses of AE and EE mice during pre-treatment fixed 7s ITI and post-treatment variable ITI testing. (e) AE mice did not show differences in changes in impulsivity between fixed and variable testing. (f) However, EE mice showed a significant change in impulsiveness between the testing sessions. n=12–15/group. #p<0.05 for effect of treatment. *p<0.05 for effect within the group. All data are expressed as ± s.e.m.

Ethanol-Induced Impulsive Mice Exhibit Anxiety-like Behavior

We tested both cohorts (continuous and abstinent) of mice in Open Field chambers to observe locomotion and centralized exploratory activity. However, to assess the longevity of any developed phenotype, we tested each cohort at different time points in the schedule. The “continuous cohort” was tested the day before the variable testing began. There were no differences between AE and EE mice in overall locomotion [t(18)=0.955, p=0.352, Fig. S3A], but the EE mice spent a significantly lower amount of time in the center of the arena [t(18)=2.364, p=0.03, Fig. S3B]. The “abstinent cohort” was tested in the Open Field twenty days after the last ethanol treatment. AE and EE mice did not display differences in overall locomotion [t(24)=0.316, p=0.755, Fig. S3D], but the EE mice still displayed significantly lower time within the center of the arena [t(24)=2.393, p=0.025, Fig. S3E].

Ethanol-induced Impulsivity Did Not Alter Cognitive Function

We tested whether our ethanol exposure paradigm affected cognition through assessing spontaneous alternation behavior within a y-maze. Briefly, this task allowed mice to explore each arm freely. An error was scored if the animal backtracked to a previous arm instead of a subsequent one. Testing occurred approximately sixteen hours post-ethanol vapor. EE and AE mice showed no difference in spontaneous alternation behavior (SAB) scores within both cohorts [t(20)=0.367, p=0.747, t(25)=0.442, p=0.361, Fig. 3C & F].

Ethanol Exposure Does Not Increase Ethanol Drinking

An important question to ask is whether impulsivity increases ethanol drinking. To test this, the “abstinent cohort” of AE (n=5) and EE (n=12) mice followed a 2-bottle choice paradigm to measure ethanol consumption and preference. Ethanol consumption as well as preference were similar between AE and EE mice (F1,14=1.719, p=0.211, Fig. S4A for consumption; F1,14=0.036, p=0.852, Fig. S4B for preference). Consumption and preference showed a main effect over session (F7,98=98.99, p<0.01, Fig. S4A for consumption; F7,98=16.52, p<0.01, Fig. S4B for preference).

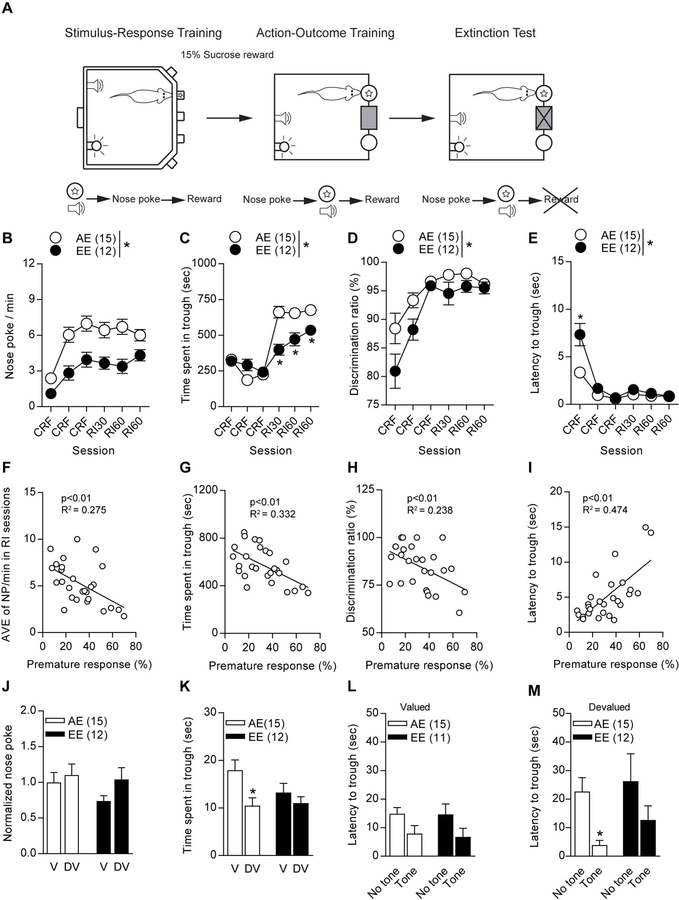

Ethanol Exposed Mice Display Decreased Sucrose Seeking Behavior

After being reinstated to the ethanol treatments for seven days, the “abstinent cohort” was trained in the action-outcome task in order to observe reward-seeking behavior (Fig. 4A). During continuous schedule of reinforcement (CSR) and random interval (RI) sessions, EE mice displayed a significant reduction in nose-pokes per min (F1,25=23.29, p<0.01, Fig. 4B) as well as a main effect over sessions (F1,125=17.82, p<0.01, Fig. 4B). Time spent in reward trough was significantly reduced as there was a main effect between groups (F1,25=7.123, p=0.013, Fig. 4C) and in sessions (F5,130=63.13, p<0.01, Fig. 4C) in EE mice. An interaction was found between groups and sessions (F5,130=10.58, p<0.011, Fig. 4C). EE mice were shown to have a significant decrease in discrimination ratio percentage (F1,25=7.579, p=0.011, Fig. 4D) and had a main effect over the sessions (F5,130=22.82, p<0.01, Fig. 4D). Interestingly, EE mice took significantly longer to retrieve their reward with the main effect observed between groups (F1,25=13.4, p<0.01, Fig. 4E) and sessions (F5,125=61.86, p<0.01, Fig. 4E). Interaction between groups and sessions was also found (F5,125=11.35, p<0.01, Fig. 4E) Linear regression analyses show a correlation of reward-seeking behavior and premature responding in the 5-CSRTT. We found a significant correlation between 5-CSRTT percent premature responses and nose-pokes per min (F1,25=9.504, p<0.01, R2=0.275, Fig. 4F), time spent in trough (F1,25=12.42, p<0.01, R2= 0.332, Fig. 4G), discrimination ratio percentage (F1,25=7.787, p<0.01, R2=0.238, Fig. 4H) and latency to trough (F1,25=22.53, p<0.01, R2=0.474, Fig. 4I). Additionally, we aimed to correlate sucrose seeking behavior with omission rates during the 5-CSRTT. We found a significant correlation between 5-CSRTT omissions and nose-pokes per min (F1,25=16.68, p<0.01, R2=0.400, Fig. S6A), time spent in trough (F1,25=18.55, p<0.01, R2= 0.426, Fig. S6B), discrimination ratio percentage (F1,25=6.734, p<0.01, R2=0.212, Fig. S6C) and latency to trough (F1,25=6.79, p<0.01, R2=0.214, Fig. S6D).

Figure 4.

Action-outcome testing displays decreased sucrose seeking behaviors toward the sucrose reward. (a) Schematic describing experimental training timeline from 5-CSRTT to action-outcome task. (b) EE mice showed decreased nose-poking per min, (b) time spent in the trough, (d) lower discrimination ratio, and (e) higher latency to trough. Linear regression analysis showed significant correlation with the percent premature response rate in the 5-CSRTT in (f) average nose-pokes per min, (g) time spent in trough, (h) discrimination ratio, and (i) latency to trough. Devaluation testing revealed no differences within or between groups in (j) nose-poking behavior. (k) AE mice showed significantly less time spent in the trough during devalued testing, but no differences in EE performance. (l) Latency to trough did not differ within or between groups during devaluation testing. (m) AE mice displayed decreased latency to the trough when a tone was presented during devaluation testing, where EE mice did not display this difference. *p<0.05 for effect of treatment. All data are expressed as ± s.e.m.

Next, the mice were subjected to a devaluation test to investigate whether they show goal-directed or habitual seeking behavior toward the sucrose reward. Interestingly, AE and EE mice showed habitual seeking behavior since neither group showed significant difference between their valued and devalued states [t(28)=0.498, p=0.623 for AE, t(22)=1.678, p=0.108 for EE, Fig. 4J]. However, AE mice spent less time in the reward trough during their devalued test [t(14)=2.396, p=0.031, Fig. 4K], whereas the EE mice did not show this difference between testing sessions [t(11)=0.914, p=.380, Fig. 4K]. Furthermore, both groups show similar latency to the reward trough with or without a tone being sounded during the valued testing session [t(14)=1.779, p=0.097, t(10)=1.495, p=0.166, AE, EE respectively, Fig. 4L]. In contrast, AE mice showed significantly lowered latency to the reward trough whenever a tone was presented during the devalued session [t(14)=3.411, p<0.01, Fig. 4M], while the EE mice still showed no difference [t(11)=1.081, p=0.303, Fig. 4M].

DISCUSSION

Our findings provide strong evidence that binge-like ethanol exposure induces maladaptive waiting impulsivity. Impulsivity is regarded as a trait or endophenotype that may predispose individuals to AUD development, as opposed to being derived from a learned behavior (Robbins et al., 2012). Our findings suggest that maladaptive impulsivity can be induced, or exacerbate an innate impulsivity trait. This is consistent with the evidence of development of disruptive impulsive behavioral changes in human subjects who had no maladaptive impulsivity prior to AUD (Sanchez-Roige et al., 2016).

Several studies show that a waiting impulsivity trait can be induced with ethanol exposure in animal models. For example, repeated ethanol intraperitoneal injections during adolescence increases waiting impulsivity in mice (Sanchez-Roige et al., 2014). In rats, both intragastric gavage and a liquid diet ethanol exposure promotes waiting impulsivity (Irimia et al., 2015; Semenova, 2012). In contrast to our study, Irimia et al used a 14-day repeated ethanol liquid diet and 9-day abstinent periods to induce impulsivity. However, following the standard 5-CSRTT training protocol (~40 days) and completing their exposure experiments (~81 days), they achieved their results after 120 days. In the present study, we streamline 5-CSRTT training and ethanol vapor exposures in order to induce impulsivity phenotype within 40 days. Additionally, mice may vary in their overall consumption of the ethanol liquid diet, leading to differing blood ethanol levels, whereas the vapor model has greater control over this variable. Semenova et al provides a strong series of experiments that focus on adolescent rats that are given intragastric gavage every 8 h for 4 days before testing for impulsivity. In our study, we focus on a repeated 4 h binge-like vapor exposure schedule. Our study describes how early adulthood exposure to ethanol vapor affects subsequent manifestation of adult impulsivity. Overall, our study builds on these findings by focusing on the effects of ethanol on impulsivity, anxiety, and sucrose seeking behavior in a time-efficient method in adult mice. These experimental paradigms had long periods of ethanol exposure and abstinence to examine impulsive-like behaviors and, therefore, have seldom been able to investigate possible links to habitual behaviors or provide evidence for brain-region specific neural activity. Our study provides a straight-forward experimental paradigm that allows for the development of ethanol-induced impulsivity. In the ethanol vapor-induced impulsivity model outlined in our report, mice are trained to perform the 5-CSRTT while also receiving ethanol vapor treatments to produce an ethanol-induced impulsive phenotype. These series of experiments allows the resulting impulsive phenotype to form within four weeks, marking a reduced time commitment compared to traditional behavior and ethanol-impulsive protocols (Bhandari et al., 2016). Although the mice face only fifty trials as opposed to one hundred, learning this demanding cognitive task occurs in an effective manner. Throughout testing, three mice showed signs of ethanol sensitivity (decreased movement and loss of weight) and subsequently died within 16 hours of ethanol vapor treatment. These mice were excluded from the study. All of the remaining EE mice faced withdrawal symptoms such as increased anxiety-like behavior, which became more apparent as testing progressed. Notably, we observed that the omission rate is higher in EE mice, which is likely due to decreased overall movement from ethanol withdrawal (Perez and De Biasi, 2015) but not observed in our Open Field data. Nonetheless, these mice still performed above eighty percent accuracy, while still exhibiting higher percentage of premature responses than the control group. Percentage of premature responses was calculated to correct for the increased amount of omissions.

Neurobehavioral addictive phenotypes have been shown in the well-established chronic intermittent ethanol (CIE) treatment schedule in rodents (Lee et al., 2016; Walker et al., 2010). Though initially designed for rats, ethanol vapor has proven quite useful in mouse studies (Ayers-Ringler et al., 2016; Hinton et al., 2012). Our study does not utilize pyrazole, an alcohol dehydrogenase inhibitor, so that the mice can quickly recover from the ethanol treatment before the next 5-CSRTT session. Importantly, acute ethanol withdrawal (<12h since last exposure) can bring a plethora of short term behavioral changes (Becker, 2000). Thus, 5-CSRTT sessions always occurred at least 16h from exiting the ethanol vapor. We also demonstrate the lasting effect of the ethanol treatments by eliminating it three days prior to variable impulsivity testing in the “abstinent cohort”. By the end of the impulsivity tests, the mice had been ten days off of the treatment, which is a substantial duration for mice to experience withdrawal and begin recovering (Becker, 2000; Lee et al., 2016). The increase in premature responding became stable across the last five days of testing, suggesting that this behavior is connected to changes within brain inhibitory circuitry as opposed to being a reaction to the short withdrawal period after an ethanol treatment. Furthermore, the anxiety-like behavior seen in the continuous cohort was also demonstrated in the “abstinent group” twenty days after the last ethanol exposure. Prior to the initiation of ethanol treatments, the mice were tested to evaluate baseline impulsiveness using a 7s ITI (Isherwood et al., 2017). In contrast to the “continuous cohort”, baseline premature responses faced an irregular pattern in the “abstinent cohort”. Responses overall were much lower than the “continuous cohort” initially (40% vs 10%). Despite this difference, both groups ended baseline training with a stable percentage below 20%. Importantly, the mice were distributed evenly into two groups based on the 7s ITI test and the treatment schedule commenced. We chose to compare AE and EE 7s ITI impulsive performance to their variable ITI performance since the amount of training given and the decreases in light duration (LD) would severely affect the retesting at the 10s LD 7s ITI parameters. This data suggests that initial impulsiveness may have little influence on the possible trigger effect ethanol has on maladaptive impulsivity.

Several significant interactions were found within our data between treatment and testing sessions. First both the “continuous” and “abstinent” cohorts displayed an interaction within their omission rates. Since there was no main effect on treatment, at which there was no ethanol exposure at this point for either group, these results are a product of behavioral variance of the mice. Ultimately, over time both groups had omission rates that were similar and acceptable for 5-CSRTT performance. Second, the omission rates of the “abstinent” cohort displayed an interaction in which there were several significant time points in the post-hoc analysis. We may infer that the EE mice may start to perform more trials during variable testing as they adjust to ethanol withdrawal. The final testing day there is a stronger decrease in omission rate that may support this claim. Finally, within the action-outcome test, there was a significant difference in time mice spent in the trough during CSR and RI testing. An interaction was found and showed that the EE mice displayed less time in the trough during RI sessions. However, over time it shows that the EE mice are increasing time spent in the trough though still spending less time than the AE mice. EE mice might be becoming increasingly more interested in the sucrose reward.

One concern is the effect ethanol exposure or undergoing withdrawal has on learning. This is the main reason to expose mice to only 4 h per day, with the highest blood alcohol levels of approximately 200mg/dl. Baseline performance displayed stable accuracy and low omission rates, indicating that the mice understood how to perform the task. When the LD and ITI changed, the number of omissions increased in concurrence with the ethanol vapor exposures. The key portion of data during the time where the mice were being trained as well as being given ethanol is the percent accuracy. The percent accuracy displays correct nose pokes divided by the summation of correct and incorrect nose pokes. The EE mice may have displayed a significant drop in overall accuracy compared to the AE mice, but the accuracy does not drop below 80% which is the minimum requirement in 5-CSRTT training from standard protocols (Bari et al., 2008). During their final week of training at 2s LD 5s ITI, no differences in percent premature responding, suggesting that EE and AE mice had the similar ability when the waiting period was predictable. Additionally, the spontaneous alternation behavior is supplied to support the notion that the groups did not display significant cognitive performance issues. We do not rule out the possibility that other cognitive functions are altered. For a more robust cognitive task, the Morris water maze or Barnes maze could be used. These additional mazes can be used in a separate cohort to further characterize our ethanol vapor exposure paradigm in the future.

Interestingly, EE mice did not consume or have a higher preference for ethanol when tested in the 2-bottle choice task. It is important to note that the described long-term forced ethanol treatment method does not give any voluntary motivation for ethanol drinking. In contrast to a liquid diet, gavage, or sucrose-ethanol rewards, there is no learned association between the ethanol taste and its rewarding (or detrimental) effect since the mice do not consume or seek ethanol. Therefore, we speculate that the ethanol vapor method can induce neuronal changes involved in impulsivity without influencing motivational circuits for ethanol-drinking behavior. The impulsivity shown is not affected by learned ethanol-seeking and expectation, but is controlled toward deciphering neutral impulsivity seen in day to day activities within humans.

After completion of the 2-bottle choice task, “abstinent mice” were reinstated to their original treatment schedule for one week. These mice were then taken off of the treatments before beginning training for an action-outcome task. There have been several studies showing affective behavior alteration within animals that experience repeated ethanol treatments (Olney et al., 2018; Slawecki, 2006; Walker et al., 2010). Unlike the current study, traditional CIE exposures are designed to be 14 h in and 10 h out of the chamber (O’Dell et al., 2004). However, when mice were trained for the action-outcome task, we discovered decreased sucrose seeking behavior for the same reward given in the 5-CSRTT. This may suggest a decreased motivation due to the diminished rewarding effects of the sucrose. However, we must consider that the mice with higher omissions were the EE mice and also the ones with higher percent premature responding (Fig. S6). On the other hand, determining motivation within the 5-CSRTT is challenging, especially in our paradigm since ethanol withdrawal is affecting performance as well. In the 5-CSRTT, omission rates and accuracy are the common assessments of attention (Fizet et al., 2016). Thus, the EE mice have a deficit in attentional vigilance as it appears they are attempting to participate as described by accuracy and premature responses but do not have the ability to pay attention during longer ITI lengths (variable testing is random between 1s to 60s). This has been previously described in rats with cortical lesions in performance is largely unaffected at a short ITI but significantly altered when facing a longer ITI (Dalley et al., 2004). Thus, it is difficult to determine if decreased motivation in the action-outcome task can be indicative of motivation within the 5-CSRTT, but it is plausible that motivation could be a critical factor. Furthermore, within the devaluation task, we found higher motivation in the AE mice when hearing a reward-associated tone, while the EE mice remained indifferent. The same difference was seen in the time spent in the reward tough. It is important to note that the “abstinent cohort” faced many operant-based challenges that could explain how the nose-pokes/min during valued and devalued tests did not change in either group. Accordingly, we have found subtle differences between the groups from the tone-association data. These results imply that cue-induced retrieval of conditioned reward may facilitate collection of the reward in spite of automatic motivational driving force toward nose-poking; however, EE-potentiated impulsivity may strengthen habitual-seeking behavior.

Three basic types of impulsivity are tested in humans and rodents: waiting, stop-signal, and delay-related impulsivity (Jentsch et al., 2014). In the current study, the 5-CSRTT is used to examine waiting impulsivity, which is mainly regulated in the NAc (Moreno et al., 2013). Our paradigm could be used to investigate various brain regions and their associations with impulsive behavior. Recently, the orbitofrontal cortex has come into the spotlight in impulsivity studies, specifically for mediating control over inhibition of impulse action within stop-signal based tasks (Bryden and Roesch, 2015). Further, lesion studies have revealed that the infralimbic, anterior cingulate, orbitofrontal cortex, and NAc core significantly increase impulsive action when tested in motor disinhibition studies (Jupp et al., 2013), which is relevant to stop-signaling impulsivity. On the other hand, delay-relayed impulsivity studies, in which a larger reward is given after a longer wait period, have been mainly focused on striatal processes (Tedford et al., 2015). The delayed-discounting task is a description of cognitive-based choice impulsiveness. Several pharmacological studies have shown the role of dopaminergic, serotoninergic, noradrenergic, and glutamatergic receptor signaling in modulating impulsive action and choice through systemic or microinjection into the aforementioned neural substrates (Jupp et al., 2013). Therefore, although we need to further characterize the nature of activated neurons, our paradigm could also be useful to investigate two other forms of impulsivity; a stop-signal or delayed-discounting task.

In the present study, we used only male mice because preclinical studies show that males are generally more susceptible to maladaptive impulsivity than females, however, the specific study of sex differences of impulsivity remains understudied (Hammerslag et al., 2017). Although a significant gap exists in knowledge regarding sex differences in risk-taking behavior, some studies have reported gender differences in terms of risk-taking behavior during manic phases of bipolar disorder, a disease typified by impulsivity (Azorin et al., 2013). Thus, in the near future, sex differences need to be considered when evaluating cellular and behavioral outcomes of impulsivity. A comparison of impulsivity in male and female mice throughout our proposal can reveal critical findings that can be generalized and potentially clinically utilized to help both men and women suffering from impulse control disorders. In summary, using a novel method, we provide strong evidence that chronic binge ethanol exposure induces maladaptive waiting impulsivity in mice which remains during abstinence. We found anxiety-like behavior resulting from withdrawal lasting twenty days after the last ethanol treatment. Our method of inducing increased impulsive behavior has had no effect on ethanol preference or cognitive performance. Lastly, we discovered that the “abstinent cohort” displayed decreased motivation for the sucrose reward while exhibiting habitual-like behaviors during the devaluation testing. Though the molecular underpinnings of how exacerbated impulsivity confer vulnerability for the development of maladaptive habit formation during reward-seeking are awaiting additional research, our findings offer new insights in our understanding of AUD and maladaptive impulsive control.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by the Samuel C. Johnson for Genomics of Addiction Program at Mayo Clinic, the Ulm Foundation, the Godby Foundation, and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA018779). We thank Jonathan Calvert and Glancis Luzeena Raja Arul for additional editing of the paper.

Abbreviations:

- 5-CSRTT

5-choice serial reaction time task

- ITI

inter trial interval

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. DS Choi is a scientific advisory board member to Peptron Inc. and the Peptron had no role in preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; nor decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All the other authors declare no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Supplementary information is available at the Addiction Biology website.

REFERENCES

- Association AP (ed). (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers-Ringler JR, Oliveros A, Qiu Y, Lindberg DM, Hinton DJ, Moore RM, Dasari S, Choi DS (2016) Label-Free Proteomic Analysis of Protein Changes in the Striatum during Chronic Ethanol Use and Early Withdrawal. Front Behav Neurosci 10:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azorin JM, Belzeaux R, Kaladjian A, Adida M, Hantouche E, Lancrenon S, Fakra E (2013) Risks associated with gender differences in bipolar I disorder. J Affect Disord 151:1033–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari A, Dalley JW, Robbins TW (2008) The application of the 5-choice serial reaction time task for the assessment of visual attentional processes and impulse control in rats. Nat Protoc 3:759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari A, Robbins TW (2013) Inhibition and impulsivity: behavioral and neural basis of response control. Prog Neurobiol 108:44–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC (2000) Animal models of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Res Health 24:105–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, Lopez MF (2004) Increased ethanol drinking after repeated chronic ethanol exposure and withdrawal experience in C57BL/6 mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28:1829–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari J, Daya R, Mishra RK (2016) Improvements and important considerations for the 5-choice serial reaction time task-An effective measurement of visual attention in rats. J Neurosci Methods 270:17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouza C, Angeles M, Munoz A, Amate JM (2004) Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction 99:811–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryden DW, Roesch MR (2015) Executive control signals in orbitofrontal cortex during response inhibition. J Neurosci 35:3903–3914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman LG Jr., Liu W, Oguz I, Styner M, Crews FT (2014) Adolescent binge ethanol treatment alters adult brain regional volumes, cortical extracellular matrix protein and behavioral flexibility. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 116:142–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Boettiger CA (2009) Impulsivity, frontal lobes and risk for addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 93:237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Vetreno RP (2014) Neuroimmune basis of alcoholic brain damage. Int Rev Neurobiol 118:315–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Walter TJ, Coleman LG Jr., Vetreno RP (2017) Toll-like receptor signaling and stages of addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 234:1483–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Theobald DE, Bouger P, Chudasama Y, Cardinal RN, Robbins TW (2004) Cortical cholinergic function and deficits in visual attentional performance in rats following 192 IgG-saporin-induced lesions of the medial prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex 14:922–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day E, Copello A, Hull M (2015) Assessment and management of alcohol use disorders. Bmj 350:h715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H (2009) Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addict Biol 14:22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fizet J, Cassel JC, Kelche C, Meunier H (2016) A review of the 5-Choice Serial Reaction Time (5-CSRT) task in different vertebrate models. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 71:135–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginley MK, Whelan JP, Meyers AW, Relyea GE, Pearlson GD (2014) Exploring a multidimensional approach to impulsivity in predicting college student gambling. J Gambl Stud 30:521–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B, Hasin DS (2015) Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 72:757–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerslag LR, Belagodu AP, Aladesuyi Arogundade OA, Karountzos AG, Guo Q, Galvez R, Roberts BW, Gulley JM (2017) Adolescent impulsivity as a sex-dependent and subtype-dependent predictor of impulsivity, alcohol drinking and dopamine D2 receptor expression in adult rats. Addict Biol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper C (2009) The neuropathology of alcohol-related brain damage. Alcohol Alcohol 44:136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DJ, Lee MR, Jacobson TL, Mishra PK, Frye MA, Mrazek DA, Macura SI, Choi DS (2012) Ethanol withdrawal-induced brain metabolites and the pharmacological effects of acamprosate in mice lacking ENT1. Neuropharmacology 62:2480–2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irimia C, Wiskerke J, Natividad LA, Polis IY, de Vries TJ, Pattij T, Parsons LH (2015) Increased impulsivity in rats as a result of repeated cycles of alcohol intoxication and abstinence. Addict Biol 20:263–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isherwood SN, Robbins TW, Nicholson JR, Dalley JW, Pekcec A (2017) Selective and interactive effects of D2 receptor antagonism and positive allosteric mGluR4 modulation on waiting impulsivity. Neuropharmacology 123:249–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubczyk A, Klimkiewicz A, Mika K, Bugaj M, Konopa A, Podgorska A, Brower KJ, Wojnar M (2013) Psychosocial predictors of impulsivity in alcohol-dependent patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 201:43–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Ashenhurst JR, Cervantes MC, Groman SM, James AS, Pennington ZT (2014) Dissecting impulsivity and its relationships to drug addictions. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1327:1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jupp B, Caprioli D, Dalley JW (2013) Highly impulsive rats: modelling an endophenotype to determine the neurobiological, genetic and environmental mechanisms of addiction. Dis Model Mech 6:302–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND (2010) Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 35:217–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Nielsen DA, Butelman ER, LaForge KS (2005) Genetic influences on impulsivity, risk taking, stress responsivity and vulnerability to drug abuse and addiction. Nat Neurosci 8:1450–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KM, Coelho MA, McGregor HA, Solton NR, Cohen M, Szumlinski KK (2016) Adolescent Mice Are Resilient to Alcohol Withdrawal-Induced Anxiety and Changes in Indices of Glutamate Function within the Nucleus Accumbens. Front Cell Neurosci 10:265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu MY, Yin CY, Zhu LJ, Zhu XH, Xu C, Luo CX, Chen H, Zhu DY, Zhou QG (2018) Sucrose preference test for measurement of stress-induced anhedonia in mice. Nat Protoc 13:1686–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M, Economidou D, Mar AC, Lopez-Granero C, Caprioli D, Theobald DE, Fernando A, Newman AH, Robbins TW, Dalley JW (2013) Divergent effects of D(2)/(3) receptor activation in the nucleus accumbens core and shell on impulsivity and locomotor activity in high and low impulsive rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 228:19–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell LE, Roberts AJ, Smith RT, Koob GF (2004) Enhanced alcohol self-administration after intermittent versus continuous alcohol vapor exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28:1676–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Tousa D, Grahame N (2014) Habit formation: implications for alcoholism research. Alcohol 48:327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira LM, Bermudez MB, Macedo MJA, Passos IC (2018) Comorbid social anxiety disorder in patients with alcohol use disorder: A systematic review. J Psychiatr Res 106:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JJ, Marshall SA, Thiele TE (2018) Assessment of depression-like behavior and anhedonia after repeated cycles of binge-like ethanol drinking in male C57BL/6J mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 168:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez EE, De Biasi M (2015) Assessment of affective and somatic signs of ethanol withdrawal in C57BL/6J mice using a short-term ethanol treatment. Alcohol 49:237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Dawson D, Frick U, Gmel G, Roerecke M, Shield KD, Grant B (2014) Burden of disease associated with alcohol use disorders in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38:1068–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW (2002) The 5-choice serial reaction time task: behavioural pharmacology and functional neurochemistry. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 163:362–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Gillan CM, Smith DG, de Wit S, Ersche KD (2012) Neurocognitive endophenotypes of impulsivity and compulsivity: towards dimensional psychiatry. Trends Cogn Sci 16:81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner S, Leucht S, Lehert P, Soyka M (2008) Acamprosate supports abstinence, naltrexone prevents excessive drinking: evidence from a meta-analysis with unreported outcomes. J Psychopharmacol 22:11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha TD, Grant BF, Chou SP, Kerridge BT, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ (2018) Concurrent use of alcohol with other drugs and DSM-5 alcohol use disorder comorbid with other drug use disorders: Sociodemographic characteristics, severity, and psychopathology. Drug Alcohol Depend 187:261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samokhvalov AV, Probst C, Awan S, George TP, Le Foll B, Voore P, Rehm J (2018) Outcomes of an integrated care pathway for concurrent major depressive and alcohol use disorders: a multisite prospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 18:189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Roige S, Pena-Oliver Y, Ripley TL, Stephens DN (2014) Repeated ethanol exposure during early and late adolescence: double dissociation of effects on waiting and choice impulsivity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38:2579–2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Roige S, Stephens DN, Duka T (2016) Heightened Impulsivity: Associated with Family History of Alcohol Misuse, and a Consequence of Alcohol Intake. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40:2208–2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenova S (2012) Attention, impulsivity, and cognitive flexibility in adult male rats exposed to ethanol binge during adolescence as measured in the five-choice serial reaction time task: the effects of task and ethanol challenges. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 219:433–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slawecki CJ (2006) Two-choice reaction time performance in Sprague-Dawley rats exposed to alcohol during adolescence or adulthood. Behav Pharmacol 17:605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedford SE, Persons AL, Napier TC (2015) Dopaminergic lesions of the dorsolateral striatum in rats increase delay discounting in an impulsive choice task. PLoS One 10:e0122063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetreno RP, Yaxley R, Paniagua B, Johnson GA, Crews FT (2017) Adult rat cortical thickness changes across age and following adolescent intermittent ethanol treatment. Addict Biol 22:712–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker BM, Drimmer DA, Walker JL, Liu T, Mathe AA, Ehlers CL (2010) Effects of prolonged ethanol vapor exposure on forced swim behavior, and neuropeptide Y and corticotropin-releasing factor levels in rat brains. Alcohol 44:487–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westman JG, Bujarski S, Ray LA (2017) Impulsivity Moderates Subjective Responses to Alcohol in Alcohol-Dependent Individuals. Alcohol Alcohol 52:249–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jonsson B, Olesen J, Allgulander C, Alonso J, Faravelli C, Fratiglioni L, Jennum P, Lieb R, Maercker A, van Os J, Preisig M, Salvador-Carulla L, Simon R, Steinhausen HC (2011) The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 21:655–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrenn CC, Turchi JN, Schlosser S, Dreiling JL, Stephenson DA, Crawley JN (2006) Performance of galanin transgenic mice in the 5-choice serial reaction time attentional task. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 83:428–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarmush DE, Manchery L, Luehring-Jones P, Erblich J (2016) Gender and Impulsivity: Effects on Cue-Induced Alcohol Craving. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40:1052–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.