Using the 2014 IBM MarketScan commercial database, we compared antibiotic selection for pharyngitis, sinusitis, and acute otitis media in retail clinics, emergency departments, urgent care centers, and offices. Only 50% of visits for these conditions received recommended first-line antibiotics. Improving antibiotic selection for common outpatient conditions is an important stewardship target.

KEYWORDS: acute otitis media, antibiotic stewardship, outpatient, pharyngitis, sinusitis

ABSTRACT

Using the 2014 IBM MarketScan commercial database, we compared antibiotic selection for pharyngitis, sinusitis, and acute otitis media in retail clinics, emergency departments, urgent care centers, and offices. Only 50% of visits for these conditions received recommended first-line antibiotics. Improving antibiotic selection for common outpatient conditions is an important stewardship target.

TEXT

Improving antibiotic selection is important to optimize treatment and to minimize the risks of antibiotic resistance and adverse events and is a key stewardship target according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) core elements of outpatient antibiotic stewardship (1). The most common diagnoses for which antibiotics are prescribed in outpatient settings are sinusitis, acute otitis media (AOM), and pharyngitis, diagnoses for which antibiotics are sometimes indicated. In a previous study of antibiotic prescribing for these conditions in emergency department (ED) and office visits, first-line antibiotics (according to treatment guidelines) were prescribed in only one-half of visits when antibiotics were prescribed (2). Additionally, a previous study showed that antibiotic prescribing for conditions for which antibiotics are never appropriate (e.g., colds) varied among outpatient settings in the United States, with the highest rates of prescribing for such conditions in urgent care settings (3). However, evidence is lacking regarding antibiotic selection patterns for common conditions in retail health and urgent care settings, which are growing sites of U.S. outpatient care. Here, we compare antibiotic selection for pharyngitis, sinusitis, and AOM in retail clinics, EDs, urgent care centers, and offices, in order to target outpatient antibiotic stewardship efforts.

We used the 2014 IBM MarketScan commercial database (IBM Watson Health). Exclusion criteria and methods for linking dispensed outpatient antibiotics to visits were described previously (3). Diagnoses were determined using a previously described system (4). We included pediatric (<18 years of age) and adult (18 to 64 years of age) visits for pharyngitis and sinusitis and pediatric visits for AOM (specifically, suppurative otitis media), because there are evidence-based guidelines recommending first-line antibiotics for these conditions (4). Antibiotics were categorized using the 2016 IBM Micromedex Red Book (https://www.ibm.com/us-en/marketplace/micromedex-red-book) national drug codes and therapeutic classes.

Among antibiotic visits, we calculated the percentages of visits with first-line antibiotic therapy, defined as amoxicillin or penicillin for pharyngitis and amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate for sinusitis and pediatric AOM (2), according health care setting. To focus on uncomplicated visits, visits with parenteral antibiotics for sinusitis or AOM or antibiotics from multiple subcategories listed in Table 1 were excluded. However, pharyngitis visits with parenteral antibiotics were included, because intramuscular penicillin is a recommended first-line treatment option. The study did not require institutional review board approval, because the data were deidentified and were deemed nonhuman subject data by the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases advisor on human subjects research. Analyses were conducted using DataProbe 5.0 (IBM Watson Health) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

TABLE 1.

Antibiotic selection for pharyngitis, sinusitis, and pediatric AOM visits, according to setting, in 2014

| Condition and druga | No. (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retail clinic (n = 13,889) | ED (n = 107,820) | Urgent care (n = 474,378) | Medical office (n = 4,268,329) | Total (n = 4,864,416) | |

| Pharyngitis (pediatric and adult) | |||||

| First-line total | 3,420 (72.2) | 24,709 (51.0) | 83,994 (46.1) | 604,395 (46.3) | 716,518 (46.5) |

| Amoxicillin | 2,410 (50.9) | 20,173 (41.6) | 74,725 (41.0) | 543,659 (41.6) | 640,967 (41.6) |

| Penicillin | 1,010 (21.3) | 4,536 (9.4) | 9,269 (5.1) | 60,736 (4.6) | 75,551 (4.9) |

| Non-first-line total | 1,314 (27.8) | 23,760 (49.0) | 98,203 (53.9) | 702,066 (53.7) | 825,343 (53.5) |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 273 (5.8) | 4,614 (9.5) | 19,571 (10.7) | 133,361 (10.2) | 157,819 (10.2) |

| Macrolide | 739 (15.6) | 13,095 (27.0) | 50,553 (27.7) | 329,236 (25.2) | 393,623 (25.5) |

| Cephalosporin | 225 (4.8) | 3,362 (6.9) | 22,822 (12.5) | 195,562 (15.0) | 221,971 (14.4) |

| Quinolone | 12 (0.3) | 464 (1.0) | 1,804 (1.0) | 19,493 (1.5) | 21,773 (1.4) |

| Other | 65 (1.4) | 2,225 (4.6) | 3,453 (1.9) | 24,414 (1.9) | 30,157 (2.0) |

| Pharyngitis total | 4,734 | 48,469 | 182,197 | 1,306,461 | 1,541,861 |

| Sinusitis (pediatric and adult) | |||||

| First-line total | 5,448 (68.3) | 16,543 (48.9) | 114,047 (46.8) | 1,018,773 (45.4) | 1,154,811 (45.6) |

| Amoxicillin | 991 (12.4) | 6,205 (18.4) | 40,601 (16.7) | 401,935 (17.9) | 449,732 (17.8) |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 4,457 (55.9) | 10,338 (30.6) | 73,446 (30.2) | 616,838 (27.5) | 705,079 (27.9) |

| Non-first-line total | 2,530 (31.7) | 17,262 (51.1) | 129,480 (53.2) | 1,226,137 (54.6) | 1,375,409 (54.4) |

| Macrolide | 1,023 (12.8) | 10,541 (31.2) | 71,563 (29.4) | 613,835 (27.3) | 696,962 (27.5) |

| Cephalosporin | 405 (5.1) | 2,152 (6.4) | 32,175 (13.2) | 321,306 (14.3) | 356,038 (14.1) |

| Quinolone | 206 (2.6) | 2,119 (6.3) | 12,359 (5.1) | 163,586 (7.3) | 178,270 (7.0) |

| Other | 896 (11.2) | 2,450 (7.2) | 13,383 (5.5) | 127,410 (5.7) | 144,139 (5.7) |

| Sinusitis total | 7,978 | 33,805 | 243,527 | 2,244,910 | 2,530,220 |

| AOM (pediatric only) | |||||

| First-line total | 922 (78.3) | 20,003 (78.3) | 33,806 (69.5) | 504,098 (70.3) | 558,829 (70.5) |

| Amoxicillin | 771 (65.5) | 17,404 (68.1) | 28,302 (58.2) | 408,561 (57.0) | 455,038 (57.4) |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 151 (12.8) | 2,599 (10.2) | 5,504 (11.3) | 95,537 (13.3) | 103,791 (13.1) |

| Non-first-line total | 255 (21.7) | 5,543 (21.7) | 14,848 (30.5) | 212,860 (29.7) | 233,506 (29.5) |

| Macrolide | 139 (11.8) | 3,012 (11.8) | 6,257 (12.9) | 67,747 (9.4) | 77,155 (9.7) |

| Cephalosporin | 108 (9.2) | 2,278 (8.9) | 8,239 (16.9) | 139,014 (19.4) | 149,639 (18.9) |

| Quinolone | 0 (0.0) | 14 (0.1) | 22 (0.0) | 248 (0.0) | 284 (0.0) |

| Other | 8 (0.7) | 239 (0.9) | 330 (0.7) | 5,851 (0.8) | 6,428 (0.8) |

| AOM total | 1,177 | 25,546 | 48,654 | 716,958 | 792,335 |

First-line therapy included amoxicillin or penicillin for pharyngitis and amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate for sinusitis and AOM. Non-first-line therapy included all antibiotics not considered first-line therapy for the diagnosis of interest. To focus on uncomplicated visits, visits with multiple antibiotics were excluded if the antibiotics were from more than one of the antibiotic subcategories listed (subcategories for sinusitis and AOM included amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, macrolide, cephalosporin, quinolone, and other; pharyngitis had an additional penicillin subcategory). For example, a visit for which both a macrolide and a cephalosporin were prescribed (two different categories of non-first-line agents) would be excluded.

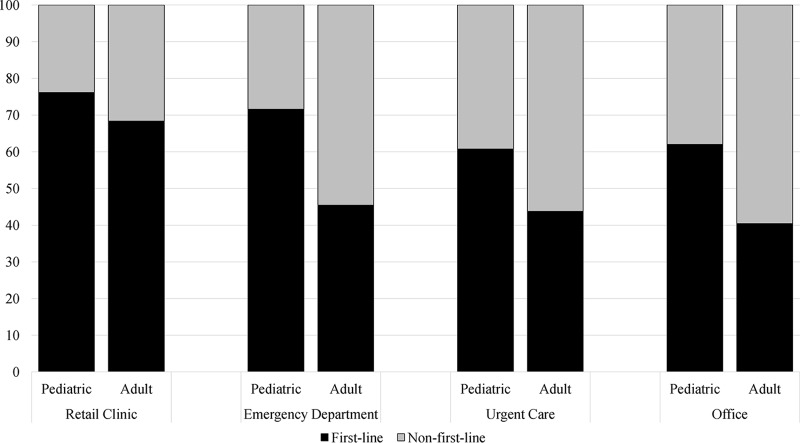

Among antibiotic visits to retail clinics (n = 13,889), EDs (n = 107,820), urgent care centers (n = 474,378), and offices (n = 4,268,329) for these three conditions, 50% received first-line antibiotics. The percentages of visits for all three conditions with first-line therapy were 70% in retail clinics, 57% in EDs, 49% in urgent care centers, and 50% in offices. In all settings, rates of first-line therapy were higher for children (62%) than for adults (41%). The rate of first-line therapy for adults was highest in retail clinics, at 68% of visits, compared with 45% in EDs, 44% in urgent care centers, and 40% in offices (Fig. 1). For pediatric AOM, rates of first-line therapy ranged from 78% in retail clinics and EDs to 69% in urgent care centers. For pharyngitis and sinusitis, retail clinics had the highest rates of first-line therapy (72% and 68%, respectively), compared with 45 to 51% of visits in the other settings (Table 1). Macrolides were the most common non-first-line therapy.

FIG 1.

First-line antibiotic selection for pharyngitis, sinusitis, and pediatric AOM, according to age, across settings in 2014. Pediatric visits included pediatric pharyngitis, sinusitis, and AOM visits that received an antibiotic. Adult visits included adult pharyngitis and sinusitis visits that received an antibiotic. First-line therapy included amoxicillin or penicillin for pharyngitis and amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate for sinusitis and AOM. Non-first-line therapy included all other antibiotics.

Only 50% of visits for common respiratory conditions received first-line antibiotics. Among outpatient settings, retail clinics had the largest proportion of visits (70%) with first-line antibiotics prescribed for respiratory conditions. Across all settings, children received first-line antibiotics more often than adults. However, all settings could improve antibiotic selection, as first-line therapy should be used in at least 80% of visits for these conditions. This target of 80% accounts for visits for treatment failures, in which the patient has already received a first-line antibiotic, and for visits by patients with reported allergies to first-line agents (i.e., penicillin-class antibiotics) (2, 5, 6).

Clinicians in retail clinics may be selecting more appropriate antibiotics for these conditions than those in other outpatient settings due to the use of protocols encouraging guideline-concordant prescribing (7). Protocols may also contribute to the similarities in first-line agent prescribing for children and adults in retail clinics. Furthermore, better antibiotic selection among children, compared to adults, in all settings coincides with decreasing U.S. outpatient antibiotic prescribing rates among children but not adults (8). These trends may be due in part to public health efforts to improve antibiotic use among children (8).

This study has limitations. We could not clinically validate diagnosis codes or facility codes in these deidentified claims data. Assumptions were required to link dispensed antibiotics to visits. Results from this convenience sample may not be generalizable. Additionally, these data are from 2014 and may not reflect the most current trends in antibiotic selection, especially because more recent data indicate that the overall use of broad-spectrum antibiotics may be decreasing slightly in the United States (9).

Antibiotic stewardship based on the CDC's core elements can be used to improve antibiotic selection (1). Lessons learned from retail clinics and pediatric visits may help improve health care quality for adults and for patients in all outpatient settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the CDC. The CDC was involved in the design of the study; analysis and interpretation of the data; review of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sanchez G, Fleming-Dutra K, Roberts R, Hicks L. 2016. Core elements of outpatient antibiotic stewardship. MMWR Recomm Rep 65:1–12. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6506a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hersh AL, Fleming-Dutra KE, Shapiro DJ, Hyun DY, Hicks LA. 2016. Frequency of first-line antibiotic selection among US ambulatory care visits for otitis media, sinusitis, and pharyngitis. JAMA Intern Med 176:1870–1872. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palms DL, Hicks LA, Bartoces M, Hersh AL, Zetts R, Hyun DY, Fleming-Dutra KE. 2018. Comparison of antibiotic prescribing in retail clinics, urgent care centers, emergency departments, and traditional ambulatory care settings in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 178:1267–1269. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Bartoces M, Enns EA, File TM Jr, Finkelstein JA, Gerber JS, Hyun DY, Linder JA, Lynfield R, Margolis DJ, May LS, Merenstein D, Metlay JP, Newland JG, Piccirillo JF, Roberts RM, Sanchez GV, Suda KJ, Thomas A, Woo TM, Zetts RM, Hicks LA. 2016. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010–2011. JAMA 315:1864–1873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piccirillo JF, Mager DE, Frisse ME, Brophy RH, Goggin A. 2001. Impact of first-line vs second-line antibiotics for the treatment of acute uncomplicated sinusitis. JAMA 286:1849–1856. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capra AM, Lieu TA, Black SB, Shinefield HR, Martin KE, Klein JO. 2000. Costs of otitis media in a managed care population. Pediatr Infect Dis J 19:354–355. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200004000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen-Turton T, Ryan S, Miller K, Counts M, Nash DB. 2007. Convenient care clinics: the future of accessible health care. Dis Manag 10:61–73. doi: 10.1089/dis.2006.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008. Progress in introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine–worldwide, 2000–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 57:1148–1151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King LM, Bartoces M, Fleming-Dutra KE, Roberts RM, Hicks LA. 2019. Changes in US outpatient antibiotic prescriptions from 2011–2016. Clin Infect Dis 68:ciz225. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]