Abstract

Wheat germ shows the highest nutritional value of the kernel. It is highly susceptible to rancidity due to high content of unsaturated fat and presence of oxidative and hydrolytic enzymes. In order to improve its shelf life, it is necessary to inactivate these enzymes by a thermal process. In this work the functional properties and some characteristics of the protein fraction of treated wheat germ were evaluated. Sequential extraction of proteins showed loss of protein solubility and formation of aggregates after heating. DSC thermograms showed that wheat germ treated for 20 min at 175 °C reached a protein denaturation degree of ~ 77%. The stabilization process of wheat germ affected significantly some functional properties, such as foaming stability and protein solubility at pH 2 and pH 8. Nevertheless, heating did not affect the water holding, oil holding and foaming capacity of protein isolates.

Keywords: Wheat germ, Protein, Functional property, Thermal processing

Introduction

Wheat germ is one of the by-products of milling industry. Separating the germ in its early stages of milling negatively affects flour quality and reduces storage stability (Zhu et al., 2006). Compared to other vegetable sources, wheat germ proteins are richer in essential amino acids, especially lysine, methionine and threonine (Zhu et al., 2006). Wheat germ also contains dietary fibre, minerals and vitamins with high antioxidant activity (Hettiarachchy et al., 1996).

Wheat germ is removed from the endosperm during milling due to its rapid deterioration despite excellent nutritional qualities. The widespread use of wheat germ in food products is limited by the action of lipases and lipoxygenases as well as the high content of unsaturated fat. Hydrolytic and oxidative enzymes causes a rapid rancidity of wheat germ during storage (less than 10 days) (Gili et al., 2017).

Since lipoxygenases are more sensitive to thermal inactivation, lipases have been the main focus for germ thermal stabilization. Several thermal processes have demonstrated to be effective in stabilizing wheat germ (Gili et al., 2017; Gili et al., 2018; Kermasha et al.,1993; Srivastava et al., 2007).

The stabilization of this by-product would allow incorporating wheat germ in the industrial formulation of food products or cosmetics due to its high content of tocopherols.

Proteins are essential components in the human diet. They also play a major role in the nutritional and sensory properties of food. Proteins possess specific functional properties, such as emulsification, foaming, gelation and water retention capacities, which facilitate processing and serve as the basis of product performance. The native structure of a protein is the net result of various attractive and repulsive interactions resulting from intramolecular and intermolecular forces as well as interaction with surrounding solvent water. Changes in the protein environment, such as temperature, solvent composition, pH and ionic strength, force the molecule to assume a new equilibrium structure. Information on protein structures and their interaction is central to understand changes in their physicochemical properties, which can be obtained through sequential-extraction procedures and electrophoresis studies (Ryan et al., 2012).

The study of the effect of stabilisation process on wheat germ proteins is relevant not only in terms of nutrition but also in term of the structure of proteins in food matrix. Liu et al. (2014a) described the calcium-induced disaggregation of wheat germ globulin under acid and heat conditions; Añón and Lupano (1986) reported the effect of heating wheat at low temperatures to preserve seed viability; and Wang et al. (2017) studied the effect of electron beam on defatted wheat germ proteins. To the best of our knowledge, no studies into the effect of thermal stabilization on the physicochemical and functional properties of wheat germ protein fraction were reported in the literature. However the effect of heat treatment on protein fraction has already been researched in other vegetal proteins such as oat (Runyon et al., 2015), pea (Peng et al., 2016), corn (Malumba et al., 2008), soy (Wang et al., 2012), and coconut (Thaiphanit and Anprung, 2016).

Thus, the aim of this work was to evaluate the extension of thermal treatment by convective heating at high temperature on enzyme inactivation and on physicochemical and functional properties of germ protein fraction. This is justified by the fact that many operations in food processing involve temperature changes; hence, it is important to reveal protein behaviour and structural changes caused by thermal processes in order to recognize the best way to incorporate wheat germ in food formulation.

Materials and methods

Materials

Raw wheat germ was kindly supplied by a local milling industry (Jose Minetti y Cia. Ltda. S.A.C.I., Córdoba, Argentina) and was sieved through a 20-mesh screen (0.841 mm), packed in polyethylene bags and stored at − 18 °C. The proximate chemical composition of the germ determined according to the standards methods of AACC (2000) was: 13.43% moisture, 27.09% protein (N × 5.25), 9.03% total lipids, ash 3.72% and 46.73% carbohydrates (by difference). All chemicals and reagents used were analytical grade.

Wheat germ stabilization

Wheat germ was treated on a convective oven (Memmert model 600 D06062, Germany). The trials were carried out at 175 ± 1 °C for 5, 10, 15 and 20 min with a fixed air velocity of 0.1 m/s. Raw wheat germ (250 g) was placed on a 25 cm diameter aluminum pan to form a uniform thin layer of about 1 cm thick. After each treatment, the material was stored in polyethylene bags and kept at −18 °C until used. Treatments were made in triplicate.

Lipase and lipoxygenase activity

Determination of lipase activity was performed as described by Gili et al. (2017). Since the hydrolytic action of lipases generates free fatty acids (FFA) from triglycerides, increase in FFA on wheat germ oil over time was considered proportional to lipase activity. To obtain the increase of FFA, germ was first moistened to get the optimal water concentration for lipase activity (17% db). Then, 8 g of wheat germ samples were twice extracted with hexane (1:10 w/v) and the free fatty acid content (g oleic acid/100 g oil) of oil was measured (AOCS, 2009). The increase in acidity measured before and after incubation of wheat germ for 48 h at 40 ± 1 °C was used to quantify lipase activity. It was expressed as g oleic acid/100 g oil. The lipoxygenase (LOX) activity was estimated following Xu et al. (2012) with modifications. Briefly, an enzyme extract was prepared by mixing 1 g of wheat germ with 10 mL of acetate buffer (pH 4.5, 0.1 M) for 30 min at 4 °C and then centrifuged at 12,000×g for 30 min. The substrate solution was prepared with 0.05 M sodium phosphate dibasic, linoleic acid (approximate concentration of 2.53 mM) and 0.08% w/v of Tween 20. The reaction system was prepared by mixing 2350 μL of phosphate buffer (pH 6.5, 0.1 M), 100 μl of substrate solution and 250 μl of diluted enzyme extract. One unit of LOX activity was defined as an increase in absorbance of 0.01 at 234 nm per minute per mg of protein under the assay conditions.

Color attributes

Color measurement of wheat germ was performed using a chroma meter (CM600d, Konica-Minolta®) through a low reflectance glass. Color was expressed according to CIE L*a*b* coordinates (Pathare et al., 2013). The browning index (BI) was calculated as:

Measurements on raw and treated samples were repeated 10 times.

Sequential extraction of proteins

Protein fractionation was performed from 300 mg of defatted wheat germ flour, following the method proposed by Steffolani et al. (2010) with modifications. Each extraction step was carried out with constant stirring, and centrifugation was done first at 10,000×g for 30 min and then for 10 min. Sequential protein extraction was performed using 3 mL of phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 6.4; F1), phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 6.4) containing 2% w/v of SDS (F2) and sample buffer (0.063 M Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 1.5% w/v SDS, 3% v/v 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% v/v glycerol and 0.01% w/v bromophenol blue; F3), for 2 h respectively in each step. The content of protein in each fraction was determined by micro-Kjeldahl method (AACC, 2000) (Nx5.45) and the protein bands were separated and characterized by SDS-PAGE.

SDS-PAGE

Electrophoresis of the fractions F1, F2 and F3 was performed using the method described by Laemmli (1970). The fractions were resuspended in sample buffer (0.063 M Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 1.5% w/v SDS, 3% v/v BME, 10% v/v glycerol and 0.01% w/v bromophenol blue) using the following quantities: 200 µL of F1 or F2, 100 mg of F3 were mixed with 100 µL of sample buffer. In the case of F3, distilled water (200 µL) was added to 100 µL of sample buffer to reach final dilution. Then, all samples were heated at 100 °C for 5 min, cooled and centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min (25 °C). The resulting supernatants comprised the protein extractions of F1, F2 and F3 under reducing conditions. Electrophoresis was performed on 70 × 80 × 0.75 mm gels using a Mini Protein II cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA). A stacking gel and a separator, with 4% and 12% acrylamide respectively, were used. Molecular weight standards were purchased from Bio-Rad (unstained SDS-PAGE Standards, broad range, #1610317). The bands were stained with 0.25% v/v Coomassie Brilliant Blue in a methanol, water and acetic acid (4:5:1 v/v) solution, and distained with methanol, water and acetic acid (4:5:1 v/v) solution.

Preparation of protein isolates

Wheat germ was defatted with hexane (1:3 w/v) for 4 h and air-dried at room temperature. Isolated proteins were obtained from defatted wheat germ by solubilization in alkaline medium (pH 9.5), followed by isoelectric precipitation (pH 4) as described by Zhu et al. (2006) The precipitate was afterwards dispersed in distilled water, neutralized, dialyzed against distilled water and freeze-dried and stored at − 18 °C. The protein isolate was used to determine protein content by micro-Kjeldahl method, thermal denaturation parameters by DSC and functional properties as detailed below. All experiments were performed in duplicate and averages were reported.

Differential scanning calorimetry

Thermal protein properties were evaluated using a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC-821e, Mettler Toledo, Switzerland). Wheat germ protein isolate was directly weighed into the aluminum pan. Then, phosphate buffer (0.01 M, pH 7.5) was added (20% w/v). Samples were heated from 30 to 120 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min. Onset temperature (To), denaturation temperature (Td), peak width at half-peak height (W) and denaturalization enthalpy (∆H) were obtained using Software STARe version 9.0x (Mettler Toledo, Switzerland).

The percentages of native protein remaining after each heat treatment were obtained from the areas under the thermogram peaks. Denaturation degree was calculated according to the following equation (Dima, et al., 2012):

where is the denaturation degree, represents the denaturation enthalpy of the raw wheat germ protein isolate, and is the denaturation enthalpy of the protein treated for different times at 175 °C.

Functional properties

Nitrogen solubility index (NSI)

NSI was determined at 0, 5 and 20 min by following the method proposed by Zhu et al. (2010). Samples (125 mg) were dispersed in 25 mL of distilled water and pH was adjusted (pH range 2–10). The suspension was shaken for 30 min at room temperature and then was centrifuged (6000×g for 20 min). The protein content was determined in the supernatant by the micro-Kjeldahl method (N×5.45). The nitrogen solubility index (NSI) was calculated from:

Water holding (WHC) and oil holding capacity (OHC)

WHC and OHC were evaluated by the modified method of Zhu et al. (2010). Wheat germ protein isolates were suspended in water or oil at 10% w/v. The suspension was mixed, held at room temperature for 30 min and centrifuged (9880×g, 20 min). WHC and OHC were calculated by weight difference per gram of dry sample, as follows:

where is weight of the dry sample and denotes weight of the sediment.

Foaming capacity (FC) and foaming stability (FS)

FC and FS were determined according to the method proposed by Zhu et al. (2010). A dispersion of protein isolate at 2% w/v in phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 7) was prepared. An aliquot of this dispersion (50 mL) was homogenized in an immersion blender (Braun MQ 700, Poland) for 1 min at room temperature, and immediately transferred to a 100 mL graduated cylinder. The total volume was registered after 0, 2, 5, 8, 10, 30, 40, 50 and 60 min and FC and FS were calculated from the following equations:

where is the original volume (50 mL), is the volume after whipping (ml) and is the initial foaming capacity.

Statistical analysis

All tests were carried out at least in duplicate. The data obtained were statistically treated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the means were compared by the Fisher LSD test at a significance level of 0.05, using INFOSTAT statistical software (FCA, UNC, Argentina).

Results and discussion

Wheat germ stabilization

The objective of wheat germ thermal treatment was to reduce the endogenous enzymes activity to avoid loss of nutritional or sensory attributes. Table 1 shows the effect of convective heating on enzyme activity. Severe toasting appearance on wheat germ was observed after stabilization process. After 20 min at 175 ± 1 °C the residual activity of lipase was 1.33% while for lipoxygenase the final value was 6.71%. These results agree with those reported by Srivastava et al. (2007) and Marti et al. (2014). These authors stabilized wheat germ by different methods, concluding that thermal treatment was successful to reduce enzyme activity and preserve wheat germ properties.

Table 1.

Characteristics of wheat germ treated at 175 °C for different times. Residual enzyme activity, moisture content and browning index evolution

| TT (min) | Residual enzyme activity LI (%) |

Residual enzyme activity LOX (%) |

Browning Index | Moisture content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100e ± 4.85 | 100d ± 1.95 | 43.99a ± 1.88 | 13.43d ± 1.50 |

| 5 | 38.28d ± 9.59 | 70.84c ± 2.48 | 48.99b ± 1.73 | 8.97c ± 2.01 |

| 10 | 31.09c ± 7.41 | 34.76b ± 1.73 | 50.55c ± 1.72 | 6.12b ± 1.07 |

| 15 | 17.35b ± 1.37 | 6.37a ± 0.54 | 52.33d ± 1.75 | 2.72a ± 1.74 |

| 20 | 1.33a ± 0.09 | 6.71a ± 0.01 | 55.13e ± 1.67 | 2.19a ± 1.70 |

Values are means of duplicate ± SD

TT treatment time, LI lipase, LOX lipoxygenase

Numbers in the same column follow by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Evolution of color parameters

Table 1 shows the browning index values for different treatment times. The values ranged from ~ 44 for raw germ to ~ 55 for germ treated for 20 min. A significant and continuous increase in BI as a function of treatment time was observed (p < 0.05). The variation of color during heat treatment can be attributed to non-enzymatic reactions that occur at temperatures higher than 100 °C.

Sequential extraction of proteins

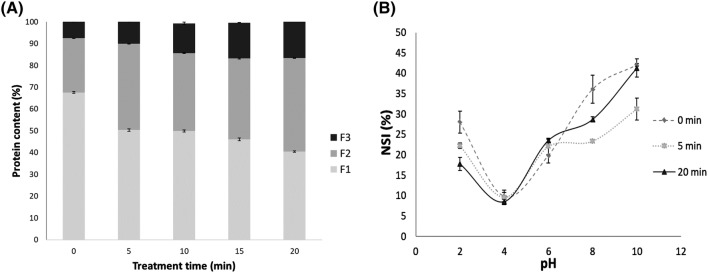

Sequential extraction with different solvents of wheat germ proteins can provide information about the effect of thermal processing on protein structure and interaction. Figure 1A shows the results of protein content in the three fractions (F1, F2 and F3) for different heating times. Raw wheat germ contained a large percentage of proteins in their soluble native state F1 (67.5%), and a 24.9% (F2) were soluble when noncovalent bonds were disrupted (hydrophobic and electrostatic). Some differences were found between raw and heat-treated samples; yet the general distribution (F1 > F2 > F3) remained constant at all heating times tested, with variations only in their relative values.

Fig. 1.

(A) Sequential extraction of wheat germ proteins treated for different times at 175 °C. Protein content in different fractions (%) vs. heating time (min). F1: Fraction extracted with phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 6.9), F2: phosphate buffer + SDS, and F3: sample buffer. (B) Nitrogen solubility index (NSI) of wheat germ protein isolate treated for different times at 175 °C. Influence of pH on NSI

The F1 fraction decayed continuously up to 28% after 20 min of treatment. This loss of solubilization could be attributed to thermal denaturation that exposes hydrophobic groups buried in globular proteins increasing their tendency to form aggregates. This behavior was also observed in pea and soy proteins (Peng et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2012).

Fractions F2 and F3 showed the opposite: they increased over heating time. F2 almost doubled their quantity after 20 min of thermal treatment and F3 grew from 7.6 to 18.6%. The increase in time of F2 and F3 could result from the fact that the accumulation of heat induced larger-sized aggregates that were originally in the F1 fraction.

Malumba et al. (2008) observed a similar heat effect on corn kernel: a substantial decrease in salt-soluble protein and an increase in protein solubilized by dissociating agents such as SDS.

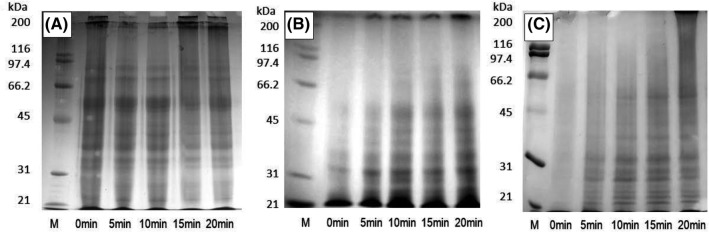

Figure 2 shows the electrophoretic patterns of wheat germ corresponding to F1, F2 and F3 fractions. Nine bands were identified in soluble native state (F1): ~ 81,000, ~ 67,400, 49,600–46,200, ~ 38,000, ~ 34,800, ~ 32,000, ~ 30,600, ~ 27,500 and ~ 25,900. Some soluble polypeptides with low molecular weight (< 35,000) disappeared after 10 min of thermal treatment. As the disappearance started at early stages, these fractions could be attributed to albumin, the most heat-sensitive protein mainly responsible for enzyme activity (Malumba et al., 2008).

Fig. 2.

SDS-PAGE profiles of sequential extraction of wheat germ proteins treated for different times at 175 °C. F1: Fraction extracted with phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 6.9) (A), F2: phosphate buffer + SDS (20 g L-1) (B) and F3: sample buffer (C). First line (M) contains molecular weight standard

The most significant protein bands on wheat germ protein isolate observed by Hettiarachchy et al. (1996) appeared in F1 fraction. The 49,600–46,200 band could also be attributed to 8S-like globulin, while “11-S globulin” or tricticins could be arrogated to the 38,000 band and a minor monomer with lower molecular mass (20,000), which could not be clearly distinguished in these gels (Zhu et al., 2006).

The disappearance of high-molecular mass fractions that did not enter the gel during the first stages of heating could be attributed to solubilization of fractions that re-appeared as aggregates after 15 min of heating (Fig. 2A). These aggregates also evidence irreversibility. In oats a similar behavior was observed with solubilization at early heating stages due to dissociation of proteins, followed by formation of soluble aggregates that induced the formation of insoluble aggregates at prolonged heating treatments (Runyon et al., 2015).

Liu et al. (2014) suggested that thermal aggregates of wheat germ globulins contain mostly noncovalent interactions (hydrophobic, van der Waals and ionic interactions).

Fraction F2 contains 6 low intensity bands, observed after 20 min of heating treatment (Fig. 2B): ~ 62,700, ~ 49,000, ~ 44,900, ~ 42,100, ~ 39,200 and ~ 36,900, ~ 36,900 being the stronger dyed band. In all cases the intensity of the lower molecular band increased in time, indicating that most of the proteins of raw wheat germ were soluble proteins in their native state and tended to form soluble and insoluble aggregates when denatured. According to the results found during the treatment of insoluble fraction with SDS, these polypeptides mainly comprised small- (< 50,000) and large-sized (> 200,000) polypeptides. The same tendency was seen in F3, where 4 light bands could be distinguished in heat-treated germ (Fig. 2C): ~ 45,300, ~ 30,200, ~ 27,200 and ~ 25,300. The precipitate fraction showed a significant increase of band intensity with heating treatment time. Zhu et al. (2006) found that the molecular weight of wheat germ prolamines and glutenins was lower than 48,000; therefore, F3 could include these fractions.

Heat treatment caused the appearance of new bands of higher molecular weight in F3 fraction due to the destruction of the ordered structure of native proteins, leading to dissociation of subunits, unfolding of proteins, exposure of hydrophobic groups and protein aggregation (Liu et al., 2014a).

Protein content of the protein isolate

Table 2 shows the total protein content of the isolates obtained at different times of treatment at 175 °C. A variation between 80.57% and 84.93% (db) was found. The extractability of proteins significantly (p < 0.05) increased after 20 min of heat treatment, which could be ascribed to the modification of protein configuration induced by heat, making them more available to be extracted by this method.

Table 2.

Characteristics of protein isolates from wheat germ samples treated at 175 °C for different times. Thermal denaturation characteristics and functional properties of wheat germ protein isolates

| TT (min) | PC (g/100 g PI) | Thermal properties | Functional properties | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To (°C) | Td (°C) | ΔH (J/g) bs | W (°C) | DDeg (%) | WHC (g/g) | OHC (g/g) | FC (%) | FS60 (%) | ||

| 0 | 80.57a ± 0.84 | 76.6a ± 0.20 | 90.3b ± 0.59 | 1.54a ± 0.20 | 9.6b ± 0.45 | 0 | 2.23a ± 0.10 | 1.80b ± 0.07 | 85b ± 1.41 | 94.13c ± 1.57 |

| 5 | 80.67ª ± 0.92 | 81.5b ± 1.85 | 89.6ab ± 0.42 | 1.25b ± 0.01 | 7.8a ± 0.03 | 18.73 | 2.31a ± 0.04 | 1.48ab ± 0.04 | 76ab ± 5.66 | 63.75b ± 15.91 |

| 10 | 81.88ab ± 1.95 | 81.4b ± 1.17 | 89.8ab ± 0.43 | 1.21b ± 0.07 | 7.7a ± 0.36 | 21.40 | 2.29a ± 0.11 | 1.45a ± 0.03 | 70a ± 5.66 | 68.53b ± 8.02 |

| 15 | 83.13ab ± 1.68 | 82.4b ± 0.38 | 89.2a ± 0.19 | 1.13b ± 0.01 | 7.8a ± 0.19 | 26.76 | 2.25a ± 0.34 | 1.55ab ± 0.23 | 68a ± 5.66 | 73.44bc ± 2.21 |

| 20 | 84.93b ± 0.26 | 82.5b ± 0.89 | 88.8a ± 0.32 | 0.35c ± 0.01 | 7.0a ± 0.80 | 77.26 | 2.27a ± 0.26 | 2.11c ± 0.13 | 68a ± 2.83 | 32.47a ± 5.51 |

Values are means of duplicate ± SD

TT treatment time, PC total protein content of the protein isolate, PI Protein isolate, To onset temperature, Td denaturation temperature, ΔH denaturation enthalpy, W width at half-peak height of wheat germ protein isolate, DDeg protein denaturation degree, WHC water holding capacity, OHC oil holding capacity, FC foaming capacity, FS60 foaming stability at 60 min

Numbers in the same column follow by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05)

The percentage of total protein content was in the range of 75.38–88.50%, found in the literature for raw wheat germ protein isolate (Hassan et al., 2010; Hettiarachchy et al., 1996; Pathare et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2006).

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Thermograms had an endothermic peak between 88 and 90 °C, which was related to the protein denaturation process as already reported by other authors for raw wheat germ (Añón and Lupano, 1986; Zhu et al., 2006). Table 2 shows the DSC results obtained for different heating times. As heating time increased, thermogram peaks were considerably narrowed, as shown by the values of width at half-peak height (W). The onset temperature (To) increased significantly as a consequence of heating treatment and no significant influence of heating time. Denaturation temperature (Td) showed a slight decrease after 15 min of heat treatment. Finally, denaturation enthalpy (ΔH) significantly decreased as a result of heating treatment. Denaturation enthalpy varied from 1.54 J/g for raw wheat germ to 0.35 J/g for the longest heating treatment (20 min). This variation corresponded to a 77.26% degree of protein denaturation in relation to untreated wheat germ, while less than 30% of DDeg was reached after 15 min. This behavior was attributed to the loss of the ordered secondary structure of the sample proteins, indicating irreversibility of the process of protein denaturation (Ge et al., 2000).

Lupano and Añón (1986) and Zhu et al. (2006) reported ΔH values for raw wheat germ protein isolate in the range of 0.76 to 1.48 J/g. Lupano and Añón also found that ΔH of wheat seeds decreased with heating treatment.

Functional properties

Nitrogen solubility index (NSI)

Figure 1B shows protein solubilization as a function of pH, with a minimum at pH 4 (isoelectric point of wheat germ proteins). For pH values higher than the isoelectric point, solubility increased continuously. Other authors (Ge et al., 2000; Hassan et al., 2010; Hettiarachchy et al., 1996) reported, for raw wheat germ, a NSI of 50–70% between pH 6 and pH 10, reaching 80% NSI at pH 12. The values obtained in the present study were lower than those reported with a maximum NSI of 40% at pH 10.

In general, the NSI of wheat germ was not affected by heat treatment. Only at pH 2 and pH 8, protein solubility decreased significantly (p < 0.05). Thermal protein denaturation is expected to cause protein aggregation due to strong protein–protein interaction, with the consequent solubility reduction. This effect was observed on oats subjected to long treatments (Runyon et al., 2015). In other matrices, like coconut, an increase in NSI was observed with heat treatment due to the exposure of previously buried hydrophilic groups (Thaiphanit and Anprung, 2016).

As NSI is an excellent index of protein functionality, it is important to underline that high temperature (175 ± 1 °C) thermal treatment did not affect significantly the solubility of wheat germ proteins at general food pH range, which may not promote the formation of precipitate when added to food formulation (Ge et al., 2000; Liu F et al., 2014).

Water holding (WHC) and oil holding capacity (OHC)

Table 2 shows WHC and OHC obtained for wheat germ protein isolate at room temperature. The values for WHC and OHC for raw wheat germ were 2.23 g/g and 1.80 g/g, respectively. The WHC obtained in this work is in agreement with those reported in the literature, whilst OHC values are higher, ranging between 1.50 and 1.04 g/g (Hassan et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2010). No significant difference (p < 0.05) was found on the WHC of wheat germ protein isolate resulting from thermal treatment at 175 °C. On the other hand, OHC showed a small but significant increase after 20 min of treatment, attributed to the conformational protein changes during heating treatment. OHC is a measurement of the interaction of non-polar residues of proteins with lipid molecules. This could be a positive characteristic considering food formulation since the binding of flavour compounds (particularly aroma compounds) has been correlated with the hydrophobic residues of proteins (Gurrieri, 2004).

Foaming capacity (FC) and foaming stability (FS)

Table 2 illustrates FC and FS for wheat germ isolates. FC for raw wheat germ was 85% and decreased to 68% after 20 min of thermal treatment. These values were lower than those obtained by Zhu et al. (2010) and Wang et al. (2017), which ranged between 100 and 260%. The progressive reduction of FC over heating time is related to the degree of protein denaturation, resulting from the loss of structure due to thermal treatment. The formation of aggregates prevents proteins from be dissolved and avoids the formation of a cohesive layer of protein around gas (Wang et al., 2017).

As expected, FS was also severely affected by thermal treatment. Less stable structures were formed with partially denatured proteins. The decay of stability is notable from 5 min of thermal treatment.

In conclusion, the present work showed the heat-induced changes of wheat germ protein fraction during thermal stabilization. Thermal treatment for 20 min at 175 °C led a considerable enzyme inactivation of lipase and lipoxygenase. Isolates with high protein content were obtained by isoelectric precipitation after different heating times. Denaturation degree of proteins reached about 77% after 20 min of treatment at 175 °C. Sequential extraction procedure reveals the presence of noncovalent bonds in native proteins and the loss of protein solubility and formation of aggregates after heating. Some heat-induced aggregates had a high molecular weight (> 200,000). However, this tendency to form aggregates did not affect significantly the nitrogen solubility index. In general, the evaluation of the functional properties of heat-treated wheat germ showed that the stabilized germ at 175 °C by convective heating is a suitable ingredient for food formulation.

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly acknowledge Consejo Nacional de Investigación Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Universidad Nacional de Córdoba-Argentina (UNC) and Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica for financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Silvina Patricia Meriles, Email: silvinameriles@agro.unc.edu.ar.

Maria Eugenia Steffolani, Email: eusteffolani@agro.unc.edu.ar.

Alberto Edel León, Email: aeleon@agro.unc.edu.ar.

Maria Cecilia Penci, Phone: ++ 54 351 156287171, Email: cecilia.penci@unc.edu.ar.

Pablo Daniel Ribotta, Email: pribotta@agro.unc.edu.ar.

References

- AACC. Approved method of the AACC. 10th ed. St Paul, MN. USA (2000)

- AOCS. Official methods and recommended practices of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 5th ed. AOCS Press. Champaign, Il, USA (2009).

- Añón MC, Lupano CE. Denaturation of wheat germ proteins during drying. Cereal Chemistry. 1986;63:259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Dima JB, Barón PJ, Zaritzky NE. Mathematical modeling of the heat transfer process and protein denaturation during the thermal treatment of Patagonian marine crabs. Journal of Food Engineering. 2012;113:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2012.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y, Sun A, Ni Y, Cai T. Some nutritional and functional properties of defatted wheat germ protein. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2000;48:6215–6218. doi: 10.1021/jf000478m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gili RD, Palavecino PM, Penci MC, Martinez ML, Ribotta PD. Wheat germ stabilization by infrared radiation. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2017;54:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s13197-016-2437-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gili RD, Torrez Irigoyen RM, Penci MC, Giner SA, Ribotta PD. Wheat germ thermal treatment in fluidised bed. Experimental study and mathematical modelling of the heat and mass transfer. Journal of Food Engineering. 2018;221:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2017.09.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gurrieri N. Cereal Proteins. pp. 176–192. In: Proteins in Food processing. Publishing Limited,Whashington, USA (2004)

- Hassan HMM, Afify AS, Basyiony AE, Ahmed GT, Ghada AT. Nutritional and Functional Properties of Defatted Wheat Protein Isolates. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences. 2010;4:348–358. [Google Scholar]

- Hettiarachchy NS, Griffin VK, Gnanasambandam R. Preparation and functional properties of a protein isolate from defatted wheat germ. Cereal Chemestry. 1996;73:363–367. [Google Scholar]

- Kermasha S, Bisakowski B, Ramaswamy H, Van der Voort F. Comparison of microwave, conventional and combination heat treatments on wheat germ lipase activity. International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 1993;28:617–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1993.tb01313.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during Assembly of Head of Bacteriophage-T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Wang L, Wang R, Chen Z. Calcium-induced disaggregation of wheat germ globulin under acid and heat conditions. Food Research International. 2014;62:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Ogiwara Y, Fukuoka M, Sakai N. Investigation and modeling of temperature changes in food heated in a flatbed microwave oven. Journal of Food Engineering. 2014;131:142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.01.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malumba P, Vanderghem C, Deroanne C, Béra F. Influence of drying temperature on the solubility, the purity of isolates and the electrophoretic patterns of corn proteins. Food Chemistry. 2008;111:564–572. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.04.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pathare PB, Opara UL, Al-Said FAJ. Colour Measurement and Analysis in Fresh and Processed Foods: A Review. Food and Bioprocess Technology. 2013;6:36–60. doi: 10.1007/s11947-012-0867-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W, Kong X, Chen Y, Zhang C, Yang Y, Hua Y. Effects of heat treatment on the emulsifying properties of pea proteins. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016;52:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Runyon JR, Sunilkumar BA, Nilsson L, Rascon A, Bergenståhl B. The effect of heat treatment on the soluble protein content of oats. Journal of Cereal Science. 2015;65:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2015.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan KJ, Homco-Ryan CL, Jenson J, Robbins KL, Prestat C, Brewer MS. Lipid extraction process on texturized soy flour and wheat gluten protein-protein interactions in a dough matrix. Cereal Chemistry. 2012;79:434–438. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.2002.79.3.434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava AK, Sudha ML, Baskaran V, Leelavathi K. Studies on heat stabilized wheat germ and its influence on rheological characteristics of dough. European Food Research and Technology. 2007;224:365–372. doi: 10.1007/s00217-006-0317-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steffolani ME, Ribotta PD, Pérez GT, León AE. Effect of glucose oxidase, transglutaminase, and pentosanase on wheat proteins: relationship with dough properties and bread-making quality. Journal of Cereal Science. 2010;51:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2010.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thaiphanit S, Anprung P. Physicochemical and emulsion properties of edible protein concentrate from coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) processing by-products and the influence of heat treatment. Food Hydrocolloids. 52: 756–765 (2016)

- Wang J, Xia N, Yang X, Yin S, Qi J, He X, Yuan DB, Wang L. Adsorption and Dilatational Rheology of Heat-Treated Soy Protein at the Oil − Water Interface: relationship to Structural Properties. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2012;60:3302–3310. doi: 10.1021/jf205128v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Ding Y, Zhang X, Li Y, Wang R, Luo X, Li Y, Li J, Chen Z. Effect of electron beam on the functional properties and structure of defatted wheat germ proteins. Journal of Food Engineering. 2017;202:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2017.01.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Miao WJ, Guo K, Hu QS, Li B, Dong Y. An improved method to characterize crude lipoxygenase extract from wheat germ. Quality Assurance and Safety of Crops and Foods. 2012;4:26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1757-837X.2011.00120.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu KX, Zhou HM, Chen ZC, Peng W, Qian HF, Zhou HM. Comparison of functional properties and secondary structures of defatted wheat germ proteins separated by reverse micelles and alkaline extraction and isoelectric precipitation. Food Chemistry. 2010;123:1163–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.05.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu KX, Zhou HM, Qian HF. Proteins extracted from defatted wheat germ: nutritional and structural properties. Cereal Chem. 2006;83:69–75. doi: 10.1094/CC-83-0069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]