Abstract

Colonic epithelial cells comprise the mucosal barrier, and their dysfunction promotes microbial invasion from the gut lumen and induces the development of intestinal inflammation. The EP4 receptor is known to mediate the protective effect of prostaglandin (PG) E2 in the gastrointestinal tract; however, the exact role of epithelial EP4 in intestinal pathophysiology remains unknown. In the present study, we aimed to investigate the role of epithelial EP4 in maintaining colonic homeostasis by characterizing the intestinal epithelial cell-specific EP4 knockout (EP4 cKO) mice. Mice harboring the epithelial EP4 deletion showed significantly lower colonic crypt depth and lower numbers of secretory cell lineages, as well as impaired epithelial cells in the colon. Interestingly, EP4-deficient colon epithelia showed a higher number of apoptotic cells. Consistent with the defect in mucosal barrier function of colonic epithelia and secretory cell lineages, EP4 cKO colon stroma showed enhanced immune cell infiltration, which was accompanied by increased production of inflammatory cytokines. Furthermore, EP4-deficient colons were susceptible to dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis. Our study is the first to demonstrate that epithelial EP4 loss resulted in potential “inflammatory” status under physiological conditions. These findings provided insights into the crucial role of epithelial PGE2/EP4 axis in maintaining intestinal homeostasis.

Subject terms: Ulcerative colitis, Experimental models of disease, Chronic inflammation

Introduction

Intestinal homeostasis is regulated by the cross-talk between epithelial cells and stromal cells, including immune cells, fibroblasts, and vascular cells, which occurs concomitantly with the interactions between dietary nutrients and microorganisms. Prostaglandin (PG) E2 is one of the key mediators in complicated cross-talk in intestinal homeostasis. PGE2 is synthesized by cyclooxygenase 1 and 2 and acts by binding to four PGE receptors (EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4). Among these EP receptors, EP4 is known to be expressed in both colonic epithelial cells1 and in lamina propria cells, such as TH17 cells2 and naive CD4+ T cells3.

PGE2 plays a pivotal role in colonic pathophysiology, such as inflammation and cancer4–8. Indeed, multiple researchers reported the protective roles of PGE2 and EP4 in mouse experimental colitis or human inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs)9,10. For example, EP4 global knockout (KO) mice showed the more severe dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis relative to mice deficient for other EP receptor subtypes9. Administration with EP4 agonists was reported to ameliorate colitis in mouse experimental models by inhibiting the production of inflammatory cytokines from infiltrating immune cells9. Results of a phase 2 clinical trial of an EP4-selective agonist demonstrated its potential beneficial effect for ulcerative colitis patients10. However, while PGE2/EP4 signaling is known to affect many cell types, including both epithelial and stromal cells, to regulate the immune system in a pleiotropic manner, these previous studies have not clarified the role of epithelial cell-specific function of EP4 for the maintenance of colonic homeostasis under physiological conditions. Whether epithelial EP4 itself is involved in the repression of the intestinal inflammation, such as IBD, has not yet been explored. Here, we examined the colonic mucosa of epithelial cell-specific EP4 knockout (EP4 cKO) mice and showed that the lack of epithelial EP4 leads to alterations in intestinal crypt architecture and causes the inflammatory phenotype under both physiological and pathological conditions.

Results

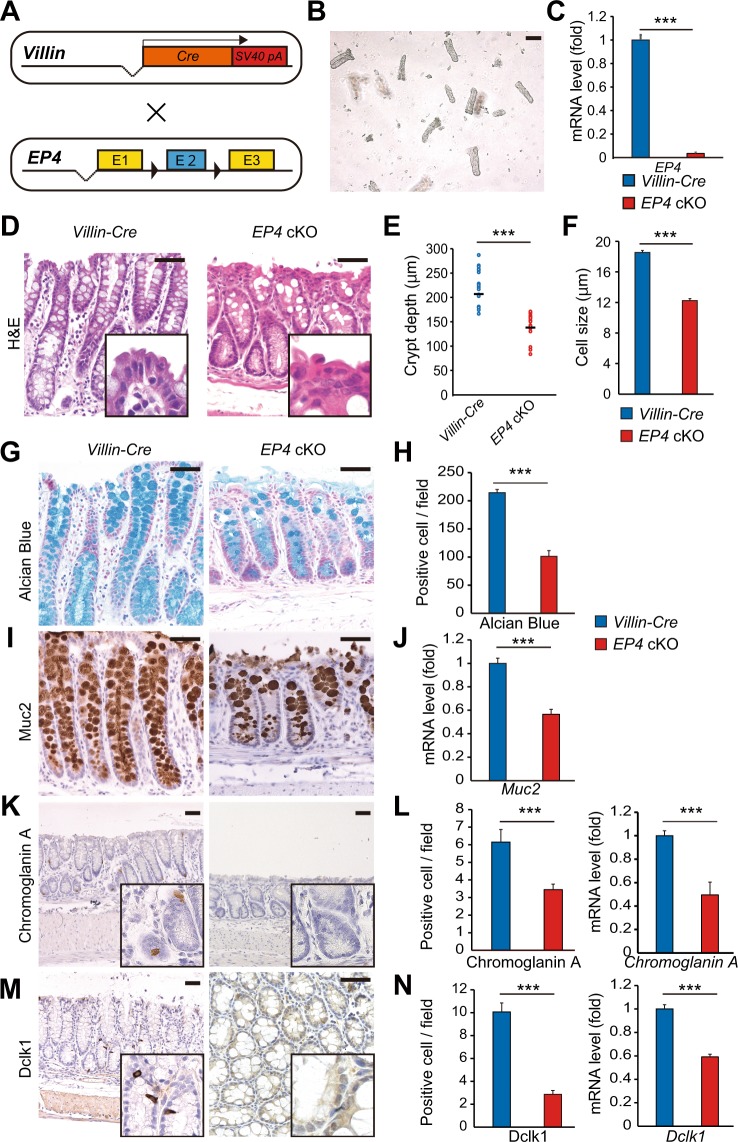

Epithelial-specific deletion of EP4 impairs colon homeostasis

Consistent with the previous reports, nearly ubiquitous expression of EP4 was observed throughout both small intestine and colon with enrichment on surface tips1,11 (Supplementary Fig. S1A). To elucidate the role of epithelial EP4 in maintaining homeostasis of the colonic epithelium, we crossed Villin-Cre and EP4flox/flox mice to generate Villin-Cre; EP4flox/flox mice (EP4 cKO) (Fig. 1A)12. Colonic epithelia were isolated from EP4 cKO mice, and EP4 deletion was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 1B,C). EP4 cKO mice were fertile, and their lifespans were comparable to control Villin-Cre mice. In addition, EP4 cKO mice were macroscopically indistinguishable from Villin-Cre mice in terms of body weight and colon length (Supplementary Fig. S1B–D). However, in histology, the depths of crypts in the distal colon were significantly lower in EP4 cKO mice than those in control Villin-Cre mice (Fig. 1D,E). Furthermore, the surface epithelial cells located at the top of crypts were smaller, irregular, and more disorganized in EP4 cKO mice compared to those in control mice (Fig. 1D,F). PGE2 coupled to EP4 receptors stimulates cAMP-dependent mucin exocytosis in the colon13,14. Therefore, we next examined the effect of epithelial EP4 deletion on secretory cell lineages in the colonic epithelium. Interestingly, results of Alcian Blue staining showed that the number of goblet cells was approximately 50% lower in EP4 cKO mice relative to that in control mice (Fig. 1G,H). EP4 cKO mice were found to have a significantly lower number of colonic epithelial cells expressing Muc2 (Fig. 1I,J). In addition, the numbers of enteroendocrine and tuft cells were significantly lower in EP4 cKO mice based on immunohistochemistry results for chromogranin A and Dclk1, respectively (Fig. 1K–N). Consistent with the above results, qRT-PCR analyses indicated downregulated expression levels of Chromogranin A and Dclk1 in EP4 cKO colons (Fig. 1L,N). Collectively, these phenotypes suggested the crucial role of epithelial EP4 in maintaining crypt structure and secretory cell lineages in the colon.

Figure 1.

Colon homeostasis is impaired in epithelial EP4-deficient mouse. (A) Schema of recombination in Villin-Cre; EP4flox/flox mice. (B) Representative microscopic view of isolated crypts. Scale bars = 100 μm. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of EP4 mRNA levels in Villin-Cre (n = 5) and EP4 cKO (n = 5) colon crypts from the mice at 8 weeks of age. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin (H,E) staining of colon for Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice. Scale bars = 50 μm. (E) Crypt length in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mouse colons (n = 4). (F) Cell size of colonic epithelial cells located in the top of colon crypts in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice (n = 3). (G,H) Alcian Blue staining and quantification in the colons from Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice at 8 weeks of age (n = 3). Scale bars = 50 μm. (I) Muc2 staining of colons in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice at 8 weeks of age. Scale bars = 50 μm. (J) qRT-PCR analysis of Muc2 mRNA levels in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice (n = 5). (K) Chromogranin A staining of colon in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice at 8 weeks of age. Scale bars = 50 μm. (L) Quantification of (K) (n = 3) and mRNA expression levels of Chromogranin A in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice (n = 4) analyzed by qRT-PCR on colon crypts. (M) Dclk1 staining of colon in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice at 8 weeks of age. Scale bars = 50 μm. (N) Quantification of (M) (n = 3) and mRNA expression levels of Dclk1 in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO colon crypts (n = 4) analyzed by qRT-PCR. Results are shown as mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.005.

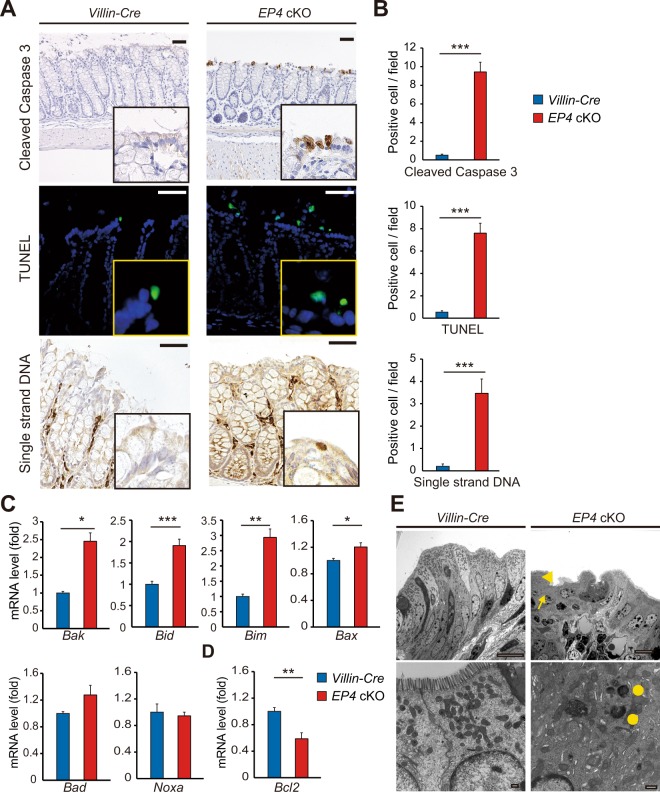

EP4 deficiency increases colonic epithelial cell death

To determine the underlying mechanisms by which epithelial EP4 loss impaired colonic homeostasis, we next examined apoptosis and proliferation status of EP4 cKO colon epithelia. Interestingly, immunohistochemistry for cleaved caspase 3 demonstrated an increase in the number of apoptotic cells, especially on the luminal surface of the colonic epithelium in EP4 cKO mice (Fig. 2A,B). Furthermore, results of TUNEL staining and single-stranded DNA staining showed a marked increase in the number of apoptotic cell as in the case of cleaved caspase 3 (Fig. 2A,B). Importantly, mRNA expression levels of apoptosis-associated genes, including Bak, Bid, Bim, and Bax, were significantly upregulated, whereas that of an anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2 was downregulated in EP4 cKO mouse colons (Fig. 2C,D). Consistent with the observed changes in apoptosis-associated genes and their roles in a mitochondrial cytochrome c-mediated cell apoptosis pathway, electron microscopy analyses revealed fewer and denatured mitochondria and irregular apical cell surface and abnormal cell polarity in EP4-deficient colonic epithelia (Fig. 2E). On the other hand, Ki67 staining revealed that proliferation was not significantly altered in EP4 cKO mouse colons (Supplementary Fig. S2A,B). Consistent with this result, we observed no significant differences in the immunostainings for β-catenin that play pivotal roles in epithelial proliferation in the intestines and the expression levels of Myc (encoding c-Myc) and Ccnd1 (encoding Cyclin D1), representative target genes of Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Supplementary Fig. S2C,D). These results also keep in line with the findings that there was no significant difference between Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice in the expression of Lgr5 and Sox9, well-established markers for intestinal stem cells (ISCs) or progenitor cells and also known as Wnt/β-catenin targets (Supplementary Fig. S2D). These results indicated the importance of epithelial EP4 for crypt cell survival but not for proliferation in colonic epithelia.

Figure 2.

Increased apoptosis in EP4 cKO colons. (A,B) Staining (A) and quantification (B) of Cleaved Caspase 3 (top), TUNEL (middle), and Single strand DNA staining (bottom) in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO colons (n = 3). Scale bars = 50 μm. (C) mRNA expression levels of apoptotic markers in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO colon crypts (n = 4) analyzed by qRT-PCR. (D) mRNA expression levels of an anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2 in Villin-Cre and EP4 colon crypts (n = 4) analyzed by qRT-PCR. (E) Representative electron microscopic views of surface epithelial cells in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO colons. Irregular apical cell surface (arrowhead), abnormal cell polarity, fewer mitochondria (arrow), and denatured mitochondria (circles) in EP4 cKO colons. Scale bars = 10 μm (top), 500 nm (bottom). Results are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005.

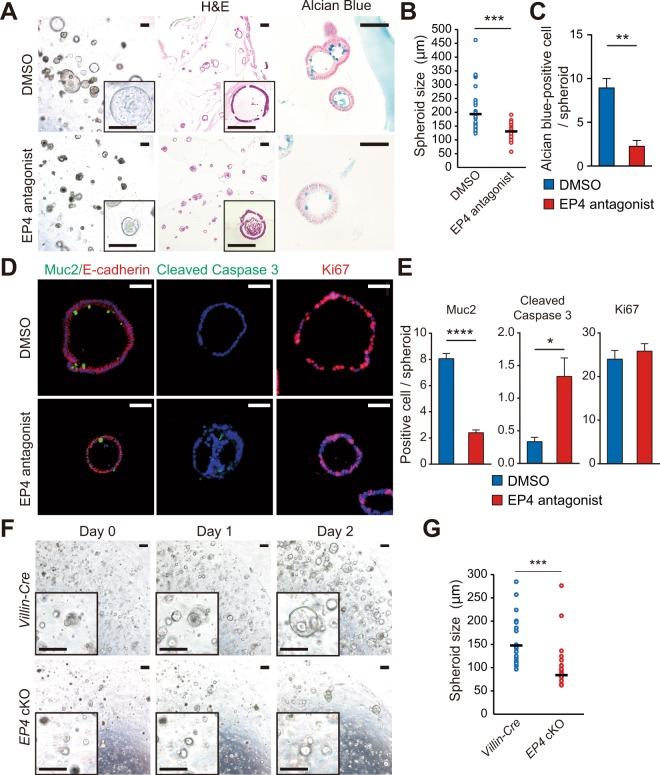

To further validate the effect of EP4 deletion on epithelial cell apoptosis, we isolated WT mouse colonic epithelia and performed 3D-spheroid culture with or without administration of the EP4 antagonist, L-161,982. At 48 h after administration with the EP4 antagonist, we observed significant defects in the spheroid growth in the EP4 antagonist-treated group (Fig. 3A,B). Consistent with the findings in the in vivo system, the numbers of Alcian blue- (Fig. 3A,C) or Muc2-positive cells (Fig. 3D,E) representing secretory cell lineages was significantly lower in mice treated with EP4 antagonist. In addition, Cleaved caspase 3 staining showed a higher number of apoptotic cells in spheroids when treated with EP4 antagonist, whereas the number of Ki67-positive proliferating cells were not altered (Fig. 3D,E). Consistent with these results, spheroids that were generated from EP4 cKO mouse colonic epithelia showed significantly impaired growth compared to those obtained from control Villin-cre mice (Fig. 3F,G). Taken together, our results clearly indicated that epithelial EP4 is required for cell survival and the maintenance of colonic epithelial cell homeostasis.

Figure 3.

Increased apoptosis in 3D-spheroid cultures of EP4 cKO colons. (A) Representative images of colon spheroids treated with or without EP4 antagonist for 48 h. 3D-culture images (left), (H,E) (middle), and Alcian blue staining (right). Scale bars = 200 μm (left, middle), 50 μm (right). (B) Diameter of spheroids treated with or without EP4 antagonist for 48 h (n = 29). (C) Quantification of Alcian blue-positive cells in (A) (n = 3). (D) Representative staining of Muc2/E-cadherin (left), Cleaved Caspase3 (middle), and Ki67 (right) on spheroids treated with or without EP4 antagonist for 48 h. Scale bars = 50 μm. (E) Quantification of Muc2, Cleaved Caspase 3, and Ki67 staining in (D) (n = 3). (F) Time-course images of spheroids generated from Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO colon crypts. Scale bars = 200 μm. (G) Quantification of day 2 spheroids in (F) (n = 50). Results are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.005, ****P < 0.001.

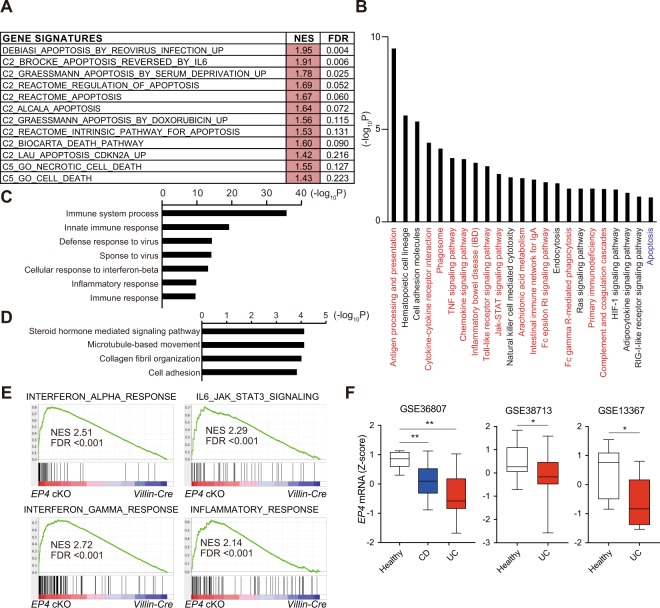

Microarray analyses indicated that deletion of epithelial EP4 enhances immune responses

To thoroughly understand the phenotype of EP4 cKO mouse colon under physiological conditions, we performed cDNA microarray analyses to compare the gene expression profiles between control Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO colon tissues. Consistent with the increased apoptosis observed in EP4 cKO epithelia, gene-set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed a significant enrichment of genes involved in apoptosis-related pathways in the EP4 cKO colons (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, results of KEGG pathway analysis using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) functional annotation tool showed significant enrichment of the “apoptosis” pathway in the genes dysregulated by EP4 deletion (Fig. 4B). However, more importantly, results of KEGG pathway analysis demonstrated that inflammation-associated pathways were highly enriched and revealed more than half of the top 20 pathways related to immune response (Fig. 4B). These findings suggested that the defects in mucosal barrier function caused by elevated epithelial apoptosis and decreased secretory cell lineages led to enhanced inflammatory activity in the EP4-deficient colonic mucosa. In support with this notion, results of gene ontology (GO) analyses suggested that biological processes, such as immune system process, innate immune response, defense response to virus, inflammatory response, and immune response, were enriched in EP4 cKO mouse colons (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, microtubule-based movement, collagen fibril organization, and cell adhesion were suppressed in EP4 cKO mouse colons (Fig. 4D). In addition, results of GSEA showed the positive enrichment of gene signatures associated with inflammatory pathways and immune reactions in EP4 cKO mice (Fig. 4E). These pathway analyses were highly consistent with the observed skewed crypt architecture and suggested the potent inflammatory phenotype in the EP4 cKO colon.

Figure 4.

Gene expression profiling revealed the potential inflammatory status of EP4 cKO colons. (A) GSEA of transcriptomic data from microarray on EP4 cKO versus Villin-Cre colons. (B) KEGG pathways positively enriched in EP4 cKO mouse colons analyzed with DAVID. (C) Biological processes (GO) positively enriched in EP4 cKO mouse colons analyzed with DAVID. (D) Biological processes (GO) negatively enriched in EP4 cKO mouse colons analyzed with DAVID. (E) GSEA plots of enrichment of the indicated gene signatures in EP4 cKO versus Villin-Cre colons using the “Hallmarks” compilation from Molecular Signature Database (MSigDB, Broad Institute). NES, normalized enrichment score; FDR, false discovery rate. (F) EP4 mRNA levels in the indicated IBD datasets. Box and whiskers graphs indicate the median and the 25th and 75th percentiles, with minimum and maximum values at the extremes of the whiskers. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

To evaluate the relevance of our findings to human patients, we compared the genes that were altered by EP4 depletion to a 92 IBD-associated gene panel that was recently reported15. Interestingly, a total of 29 genes that showed altered expression patterns in EP4-deficient colons (log2 fold change >1) was included in the IBD-associated gene panel (Supplementary Table S2). These overlapping genes encoded the molecules such as cytokines (Il1b, Il21, Il33, and Tnf), chemokines (Ccl4, Ccl2, Cxcl9, and Cxcl10), immune cell surface or derived molecules (Cd4, Cd86, S100a8, S100a9, and Nos2), bacterial sensing-associated genes (Nod2 and Lcn2), intracellular signaling molecules (Gata3 and Stat1), components of the complement system (C3 and Cd55), and adhesion factor (Icam1). Consistent with the above findings, human IBD dataset analyses demonstrated significant downregulation of EP4 mRNA expression levels in both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis patient samples relative to those in the healthy controls (Fig. 4F). Taken together, EP4-deficient colons harbored genetic alterations associated with increased apoptosis and enhanced inflammatory phenotype.

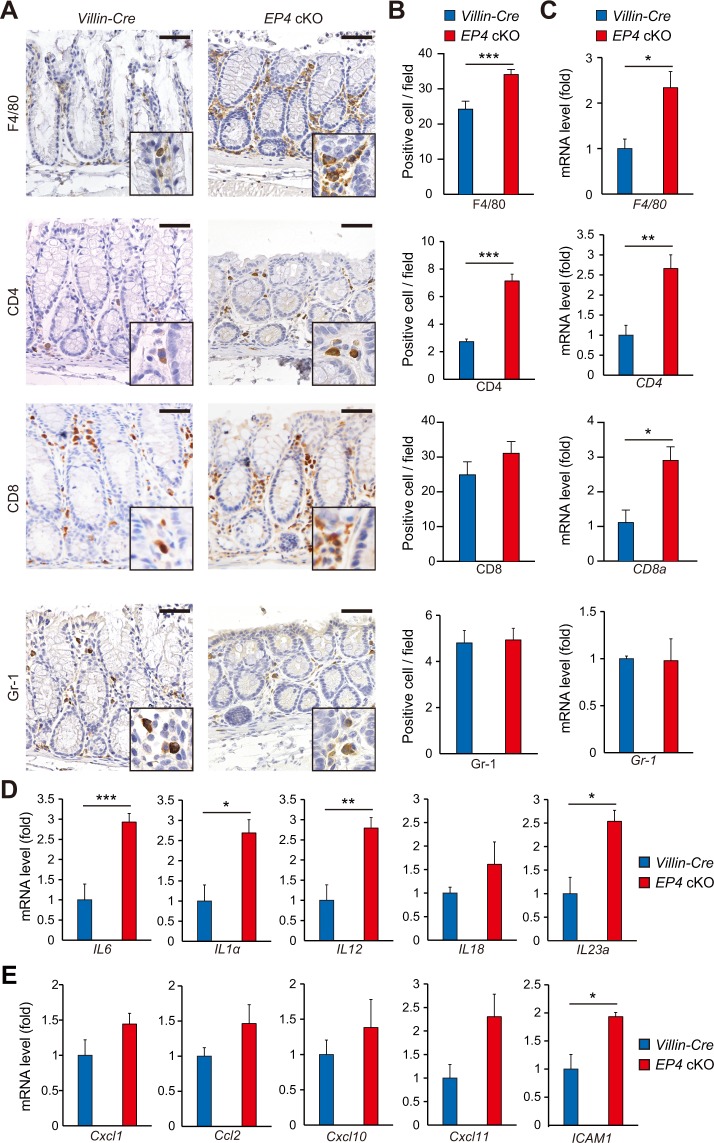

Deletion of epithelial EP4 increases immune cell infiltration in colonic stroma

To better characterize the inflammatory responses in the EP4 cKO colon, we first examined immune cell infiltrations by immunohistochemical analysis. The numbers of F4/80+ macrophages and CD4+ T cells were higher in EP4 cKO mouse colons, whereas numbers of CD8+ T cells and Gr-1+ neutrophils were not significantly different from those of control Villin-Cre mice (Fig. 5A,B). Furthermore, results of qRT-PCR analyses also showed upregulated F4/80, CD4 and CD8a mRNA expression levels in EP4-deficient colons (Fig. 5C). These data suggested that deletion of EP4 in colonic epithelia affects the stroma and leads to potential inflammatory status. Consistent with this notion, mRNA expression levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were elevated by the deletion of EP4 in the colonic epithelium (Fig. 5D,E).

Figure 5.

Immune cell infiltration in EP4 cKO colons. (A,B) Staining for F4/80, CD4, CD8, and Gr-1 (A) in colons from Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice, and quantification (B; n = 3). Scale bars = 50 μm. (C) mRNA expression levels of indicated genes in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO colons analyzed by qRT-PCR (n = 4). (D) mRNA expression levels of inflammatory cytokines in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO colons analyzed by qRT-PCR (n = 4). (E) mRNA expression levels of chemokines in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO colons analyzed by qRT-PCR (n = 4). Results are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005.

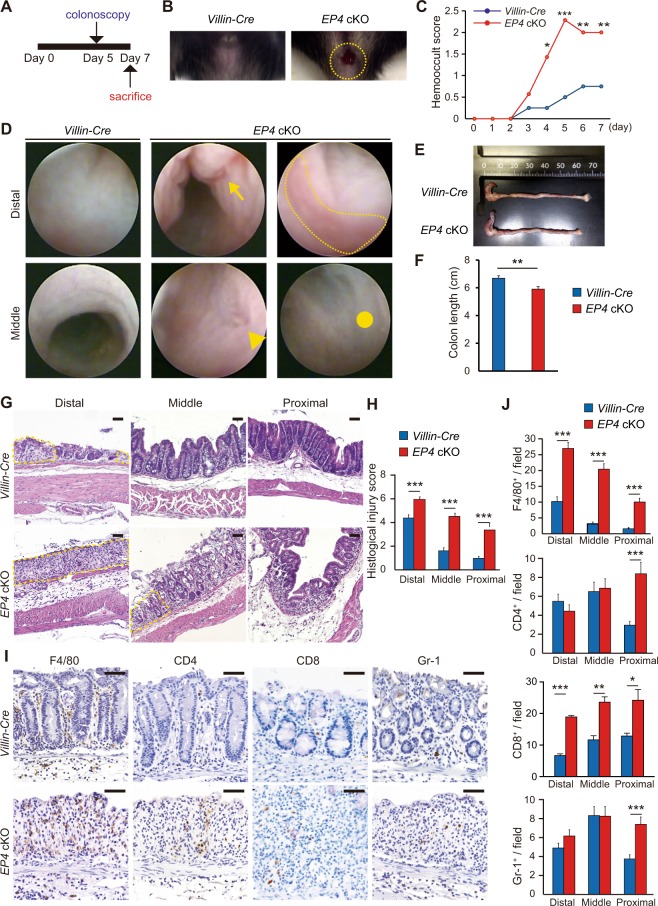

Epithelial EP4 deficiency exacerbates DSS-induced colitis

Given the potential inflammatory status of the EP4 cKO colon, we next examined a DSS-induced colitis model. To induce colitis, mice were administered with 2% DSS for 7 days and subsequently analyzed by colonoscopy, followed by macroscopic and histological analyses (Fig. 6A). EP4 cKO mice developed bloody stools after 5 days of DSS treatment (Fig. 6B). Thereafter, most DSS-treated EP4 cKO mice presented gross bleeding, whereas hemoccult was the most severe condition observed in control Villin-Cre mice treated with DSS (Fig. 6C). Results of mouse colonoscopy demonstrated multiple erosions or ulcers in DSS-treated EP4 cKO mouse colons (Fig. 6D). On day 7, macroscopic examination of the dissected colons showed that colon lengths were significantly shorter in EP4 cKO mice (Fig. 6E,F). Histologically, EP4 cKO mouse colons displayed more severe epithelial destruction and extensive intestinal ulceration relative to control Villin-Cre mouse colons (Fig. 6G). Furthermore, histological injury scores were higher in all parts of EP4 cKO colons (Fig. 6H). Infiltration with inflammatory cells, especially F4/80-positive macrophages and CD8-positive T cells, was more prominent in EP4 cKO mice (Fig. 6I,J). Thus, in addition to the potential inflammatory status under physiological conditions, EP4 cKO mice were susceptible to DSS administration and developed severe colitis.

Figure 6.

Inflammation was severely exacerbated in EP4 cKO mice in DSS-colitis model. (A) Strategy of experimental colitis with 2% DSS treatment. (B) Representative macroscopic views of the mouse anus at day 5 after starting DSS treatment. Yellow dashed circle denotes the active bleeding of EP4 cKO mice. (C) Hemooccult score at indicated time points in Villin-Cre (n = 8) and EP4 cKO mice (n = 7). (D) Colonoscopic images of distal or middle colons from Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice. Arrow denotes longitudinal erosion, arrowhead denotes ulcer, dotted line outlines inflammatory mucosa, and circle marks fibrotic region. (E,F) Representative macroscopic image (E) and length (F) of the colon from Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice at day 7 after starting DSS treatment. (n: Villin-Cre = 8 and EP4 cKO mice = 7). (G) H&E staining of colons from Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice at day 7 after starting DSS treatment. Dotted line outlines ulcerations. Scale bars = 50 μm. (H) Histlogical injury scores in Villin-Cre (n = 8) and EP4 cKO mice (n = 7) at day 7 after starting DSS treatment. (I,J) Staining (I) for F4/80, CD4, CD8, and Gr-1 of colons in Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice at day 7 after starting DSS treatment, and quantification (J). Scale bars = 50 μm. (n: Villin-Cre = 8 and EP4 cKO mice = 7). Results are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005.

Discussion

Our current findings demonstrated that intestinal epithelium-specific EP4 deletion led to a skewed crypt architecture and increased apoptosis of colonic epithelial cells, leading to a potential inflammatory phenotype that is associated with higher susceptibility to experimental colitis. These results shed light on the pivotal function of epithelial EP4 in maintaining colonic homeostasis and in suppressing the development of inflammation.

We observed no gross alterations in the appearance of intestines between control Villin-Cre and EP4 cKO mice; however, the depth of crypts in the distal colon was significantly lower in EP4 cKO mice. The intestinal epithelium is characterized by its rapid cell turnover, and equilibrium is maintained between proliferation of crypt cells and apoptosis of surface epithelial cells. In the present study, the deletion of epithelial EP4 did not affect cell proliferation in the colonic crypt. Consistent with this, factors that regulate crypt cell proliferation, such as β-catenin, c-Myc, and cyclin D1, showed no significant changes in mRNA expression levels or protein localization. These findings also keep in line with that there was no significant alteration (although slight decrease was observed in the case of Lgr5) in the expressions of ISC markers such as Lgr5 and Sox9 between EP4-deficient and -sufficient colons. However, since there is a gradient in EP4 expression in intestinal epithelium with more enrichment in surface tip than crypt bottom as we and others showed1,11, the loss of epithelial EP4 could affect more on upper part of crypt than the stem cell zone. Given that Villin-cre mouse line is an adequate model only to investigate epithelial cell biology, further studies with the selective inactivation of EP4 in stem or progenitor cell population using an ISC-specific Cre mouse targeting such as Lgr5 and Sox9 would be necessary to robustly understand the role of EP4 in ISC functions. While proliferation was not changed, the number of apoptotic cells was significantly higher in the surface epithelial cells of EP4-deficient colons. This could be explained by alterations in the mitochondrial cytochrome c-mediated cell apoptosis pathway induced by the deletion of epithelial EP4 and suggested that EP4 is required to suppress this pathway, although the detailed mechanisms by which EP4 regulates this pathway remain to be explored. Furthermore, our findings suggested that increased cell apoptosis can lead to crypt shortening, even with preserved cell proliferation potential in EP4 cKO mice. This notion is supported by our spheroid experiments showing that treatment with an EP4 antagonist did not affect spheroid proliferation but increased the rate of apoptosis, resulting in impaired spheroid growth.

The other finding of our in vivo and ex vivo models is that epithelial-EP4 loss leads to the reduction in the numbers of secretory cell lineages including goblet, tuft, and enteroendocrine cells. Secretory cells are central to control intestinal biology, and their dysfunction leads to the pathological conditions such as inflammation. Mucus, secreted by goblet cells, forms layers that separates the bulk of the luminal contents from the intestinal epithelium, whereas intestinal tuft cells regulate a type-2 immune reaction in a response to IL13 secreted by ILC2s16. Consistent with our results, recent report demonstrated the importance of PGE2/EP4 axis in mucin secretion from goblet cells in response to IL1317. Mechanistically, binding of PGE2 to EP4 receptors stimulates cAMP-dependent exocytosis in the colon. Moreover, PGE2 induced cAMP response element-binding protein/ATF1 phosphorylation, which further activates Muc2 transcription in colon epithelial cells18. On the other hand, PGE2/Cox2/Dclk1 axis is shown to be an important mediator of tuft cell function under bacterial-induced colitis by enhancing epithelial repair responses19. We here proposed the new underlying mechanism whereby PGE2/EP4 regulates secretory cell proportions possibly through inhibiting cell apoptosis. Given the crucial functions of secretory cell lineages and PGE2/EP4 signaling pathway to suppress colitis, our study has provided with an impactful evidence that links these two important regulators in control of the development of intestinal inflammation.

In addition to increased epithelial cell apoptosis, microarray analysis demonstrated that the deletion of epithelial EP4 enhanced immune and inflammatory responses. In agreement with the defect of mucosal barrier functions in EP4-deficient colons due to increased epithelial apoptosis and reduced secretory lineages, we observed greater immune cell infiltration in colonic stroma accompanied by upregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in EP4 cKO mice even though the mice were comparable to WT mice in gross appearance with normal gaining weight and life span under basal conditions. These findings suggest that epithelial EP4-deficient colons are predisposed to inflammatory phenotype. This latent inflammation of the mice with epithelial EP4-deficiency is manifested by the treatment with inflammatory stimuli such as DSS. Our observations are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that global EP4 KO mice showed downregulated expression of genes associated with tissue defense, remodeling, and immunosuppression, and upregulated expression of genes induced by IFN-γ, and revealed severer inflammation when treated with DSS9. Thus, we for the first time demonstrated that intestinal epithelium deficient for EP4 is already in pre-inflammatory condition and epithelial EP4 loss alone is sufficient to induce this phenotype in mouse colons. Although further studies are required to determine the role of stromal EP4 in the intestines, it is highly likely that the preparatory status for inflammatory stimuli is associated with increased epithelial apoptosis in EP4 cKO mice. Namely, epithelial cell apoptosis induced by EP4-deficiency, which causes defects in the intestinal barrier, might precede potential and imperceptible inflammatory status in the microenvironment. If so, it is also reasonable that EP4 cKO mice are highly susceptible to DSS treatment. Previous studies indicated that global knockout of EP4 or administration with EP4 antagonists exacerbates DSS-induced colitis9. In those experiments, EP4 receptors were deleted or inhibited in both epithelial cells and stromal cells. In epithelial cells, activation of EP4 signaling promotes mucin and bicarbonate secretion from epithelial cells13,14. In stromal cells, activation of EP4 signaling suppresses cell proliferation and Th1 cytokine production of isolated lamina propria mononuclear cells9. In fact, EP receptors are expressed in naive CD4+ T cells3, and EP4 is one of the most abundant and potent EP receptors expressed in Th17 cells2. Our current findings indicated that EP4 is required for epithelial cell survival and that EP4 deletion in epithelial cells is involved in the initiation and/or maintenance of intestinal inflammation. These findings, together with the results of our bioinformatic analyses on human IBD datasets, may contribute to a better understanding of how EP4 exerts a protective effect in human IBD10,20.

In conclusion, our study is the first to demonstrate the latent and potential inflammatory status in the colons induced by epithelial-specific EP4 deletion under physiological conditions. Notably, disruption of epithelial EP4 signaling is sufficient to produce such a phenotype. These data provide us with a clue to understand the mechanisms underlying the maintenance of colon homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Villin-Cre mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (#004586)21, and EP4 flox mice were generated as previously described12. Animals were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Animal Facilities of Kyoto University. Eight-week-old mice were used. All experiments were approved by the animal research committee of Kyoto University and performed in accordance with Japanese government regulations.

Histological analyses

Mouse colonic tissues were fixed with 4% buffered paraformaldehyde solution, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned (5 µm in thickness). Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or alcian blue. For immunohistochemistry, sections were incubated with primary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature, then with biotinylated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature; immunoperoxidase labeling was visualized with avidin/biotin complex (VECTASTAIN Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and sections were colored with diaminobenzidine substrate (Dako, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and counterstained with hematoxylin. For immunofluorescence, sections were incubated with primary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature and washed with PBS. Washed sections were incubated with fluorescent dye-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature, stained with Hoechst dye for 10 min at room temperature, and embedded with 50% glycerol. For quantitative analyses, cell numbers were counted in at least five random high-power fields from three animals for each genotype. Primary antibodies used in this study were obtained from the indicated suppliers: rabbit anti-Dclk1 (ab31704, Abcam), rabbit anti-Chromogranin A (ab15160, Abcam), rat anti-Ki67 (652402, BioLegend), rabbit anti-Muc2 (SC15334, Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-cleaved Caspase 3 (9664S, Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-E-cadherin (610182, BD Transduction Laboratories), rabbit anti-F4/80 (ab6640, Abcam), rat anti-CD4 (14-0041-85, eBioscience), rat anti-Gr1 (14-5931-85, eBioscience), mouse anti-Ctnnb1 (610153 BD Biosciences), rat anti-CD8 (550281, eBioscience), and rabbit anti-EP4 (ab133170, Abcam). TUNEL staining was performed using In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, TMR red (Roche).

Colitis model and histological injury score

To analyze the severity of colitis, mice were sacrificed after seven-days administration of 2% DSS. The colon was divided into the proximal, middle, and distal portions. Histological injury was scored as described previously20. Two parameters were measured: the extent of inflammation (0, none; 1, slight; 2, moderate; 3, severe) and the extent of crypt damage (0, none; 1, the basal one-third portion damaged; 2, the basal two-thirds portion damaged; 3, the entire crypt damaged but the surface epithelium intact; 4, the entire crypt and epithelium lost). Each score was added to determine the severity of colitis.

Colon crypt isolation

Colonic crypts were isolated according to the previous protocols22. In brief, excised colonic tissues were incubated in TrypLE™ Express Enzyme (1x) and phenol red (#12605036) for 30 min at 37 °C. After the incubation, epithelium was separated by vigorous shaking, and the remaining intestinal tissue was placed in a new tube for collection of subsequent fractions. After the isolation, crypt cells were pelleted, and passed through 100 µm cell strainers. Then, colonic crypts were collected for either spheroid culture or RNA analyses.

Spheroid culture

Conditioned medium of L-cell line secreting Wnt3a, R-spondin3, and Noggin (L-WRN CM) was prepared as described previously23. L-WRN cells were purchased from ATCC (ATCC; CRL3276). Isolated crypts of the proximal colon were embedded in Matrigel (BD Biosciences). For spheroid culture of normal epithelium, 50% L-WRN CM supplemented with 5 µM Y-27632 (Tocris Bioscience) was added to each well. For EP4 antagonist experiment, spheroids generated from control (Villin-Cre) mice were treated with or without specific EP4-antagonist L161,982 (100 µM, Sigma) for 48 h and then analyzed.

RNA extraction and analysis

Total RNA was subsequently extracted using the RNA mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA was either processed for microarray or quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Single-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using a Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche Applied Science, Basel, Switzerland). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green I Master (Roche Applied Science) and a Light Cycler 480 (Roche Applied Science). All reactions were performed in duplicate, and expression levels of mRNAs were normalized comparing to those of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA. Primers were designed using the MGH primer bank, and primer sequences are described in Supplementary Table S1.

Microarray analysis

Total RNAs from Villin-Cre and Villin-Cre; EP4flox/flox mouse whole colon tissues (n = 3, respectively) were subjected to the SurePrint G3 Mouse GE v2 8 × 60 K Microarray (Agilent). Processed signal intensities were normalized by the global scaling method. A trimmed mean probe intensity was determined by removing 2% of the lower and the higher end of the probe intensities to calculate the scaling factor. Normalized signal intensities were then calculated from the target intensity on each array using this factor, such that the trimmed mean target intensity of each array was arbitrarily set to 2500. Data were analyzed to identify gene probes that showed more than a two-fold change. The accession number for the complete microarray data reported in this paper is GEO: GSE 135859.

Bioinformatic analysis

KEGG and GO analyses on mouse microarray data (see above “Microarray analysis”) was performed by uploading the data to DAVID. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed using GSEA 3.0 software (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp) with 1000 gene-set permutations using the signal-to-noise gene-ranking metric with the collections h.all.v6.1.symbols (H), c2.all.v6.1.symbols (C2), or c5.all.v6.1.symbols (C5). Raw gene expression data inflammatory bowel disease sample datasets (GSE36807, GSE38713, and GSE13367) were directly accessed through the GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Electron microscope

The mouse colon tissues were placed in 4% paraformaldehyde with 2% glutaraldehyde for a minimum of 12 h, and cut into 1 mm thick coronal sections. Next, sections were post-fixed in 1.0% osmium tetraoxide in 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, for 2 h at room temperature, and dehydrated in a series of graded ethanol solutions. After immersion in propylene oxide, samples were immersed in a mixture (1:1) of propylene oxide and Epon812 (LUVEAC-812, Nacalai Tesque, Japan) for 1.5 h. Samples were then immersed in a mixture (1:3) of propylene oxide and Epon812 for 1.5 h and finally immersed in only Epon812 for 12 h. After immersion, samples were embedded in Epon812 resin according to the inverted beam capsule procedure and polymerized at 60 °C for 3 days. The tissue samples were cut into ultrathin sections (70 nm) on an EM UC6 ultramicrotome (Leica, Germany). The ultrathin sections were examined with an H7650 electron microscope (Hitachi, Japan).

Colonoscopy procedures

To analyze the severity of colitis in the mouse colon, we used a high-resolution miniaturized endoscopic system24–26. This system is composed of a miniature rigid endoscope, a xenon light source, a triple chip high resolution CCD camera, and an operating sheath with 3 Fr. instrument channel and water injection bulb to regulate inflation of the mouse colon (all from Karl Storz). Endoscopic images were viewed with high resolution on a flat panel color monitor.

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as mean ± SEM. Significant differences between groups were determined using a Student’s t test (two-tailed unpaired) when the data met the normal distribution tested by D’Agostino test. If the data did not meet this test, a Mann-Whitney test was used. The significance level for statistical testing was set at P < 0.05.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid KAKENHI (25112707, 26293173, 14J03460, 15J00986, 16K09394, 16K15427, 17J05511, 17H04157, and 19K16712), a research program as part of the Project for Development of Innovative Research on Cancer Therapeutics (P-Direct) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and Project for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Evolution (P-CREATE) from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. It was also supported by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, the Project for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Evolution (18cm0106142h0001), AMED-PRIME (17cm0106XXXh0001), the Kobayashi Foundation for Cancer Research, the Naito Foundation, Princess Takamatsu Cancer Research Fund, the Mochida Foundation, the Mitsubishi Foundation, the Shimizu Foundation for Immunology and Neuroscience, the Japan Foundation for Applied Enzymology, the Takeda Foundation, the Kanehara Foundation, and the Uehara Foundation. We thank Prof. Tatsuaki Tsuruyama in Department of Drug Discovery Medicine at Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine for critical assistance to analyze electron microscopy images.

Author contributions

Y.M., Y.N., A.F. and H.S. coordinated the project and designed the experiments. Y.M., T.Y., Y.Y., T.M., Y.F., M.S., T.Y., M.N., O.A., S.O., N.G. and Y.H. performed the experiments. R.M.B. provided materials that made the study possible. Y.M., Y.N., A.F. and H.S. analyzed the data. Y.M., Y.N., A.F. and H.S. wrote the manuscript with help from R.M.B.

Competing interests

Y.F. is employed by Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-51639-2.

References

- 1.Morimoto K, et al. Cellular localization of mRNAs for prostaglandin E receptor subtypes in mouse gastrointestinal tract. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G681–687. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.3.G681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boniface K, et al. Prostaglandin E2 regulates Th17 cell differentiation and function through cyclic AMP and EP2/EP4 receptor signaling. J Exp Med. 2009;206:535–548. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagamachi M, et al. Facilitation of Th1-mediated immune response by prostaglandin E receptor EP1. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2865–2874. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharon P, Ligumsky M, Rachmilewitz D, Zor U. Role of prostaglandins in ulcerative colitis. Enhanced production during active disease and inhibition by sulfasalazine. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:638–640. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(19)31672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheng H, Shao J, Washington MK, DuBois RN. Prostaglandin E2 increases growth and motility of colorectal carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18075–18081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009689200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niho N, et al. Suppression of azoxymethane-induced colon cancer development in rats by a prostaglandin E receptor EP1-selective antagonist. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:260–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mutoh M, et al. Involvement of prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP(4) in colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narumiya S, Sugimoto Y, Ushikubi F. Prostanoid receptors: structures, properties, and functions. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1193–1226. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kabashima K, et al. The prostaglandin receptor EP4 suppresses colitis, mucosal damage and CD4 cell activation in the gut. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:883–893. doi: 10.1172/JCI14459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakase H, et al. Effect of EP4 agonist (ONO-4819CD) for patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis refractory to 5-aminosalicylates: a randomized phase II, placebo-controlled trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:731–733. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyoshi H, et al. Prostaglandin E2 promotes intestinal repair through an adaptive cellular response of the epithelium. EMBO J. 2017;36:5–24. doi: 10.15252/embj.201694660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider A, et al. Generation of a conditional allele of the mouse prostaglandin EP4 receptor. Genesis. 2004;40:7–14. doi: 10.1002/gene.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeuchi K, Yagi K, Kato S, Ukawa H. Roles of prostaglandin E-receptor subtypes in gastric and duodenal bicarbonate secretion in rats. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1553–1559. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeuchi K, et al. Impaired duodenal bicarbonate secretion and mucosal integrity in mice lacking prostaglandin E-receptor subtype EP(3) Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1128–1135. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70398-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holgersen K, et al. High-resolution gene expression profiling using RNA sequencing in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and in mouse models of colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:492–506. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steele SP, Melchor SJ, Petri WA., Jr. Tuft Cells: New Players in Colitis. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22:921–924. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akaba T, et al. Activating prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP4 increases secreted mucin from airway goblet cells. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hokari R, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide upregulates MUC2 intestinal mucin via CREB/ATF1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G949–959. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00142.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yi J, et al. Dclk1 in tuft cells promotes inflammation-driven epithelial restitution and mitigates chronic colitis. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:1656–1669. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0237-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakatsuji M, et al. EP4 Receptor-Associated Protein in Macrophages Ameliorates Colitis and Colitis-Associated Tumorigenesis. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madison BB, et al. Cis elements of the villin gene control expression in restricted domains of the vertical (crypt) and horizontal (duodenum, cecum) axes of the intestine. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33275–33283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato T, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyoshi H, Stappenbeck TS. In vitro expansion and genetic modification of gastrointestinal stem cells in spheroid culture. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:2471–2482. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker C, et al. TGF-beta suppresses tumor progression in colon cancer by inhibition of IL-6 trans-signaling. Immunity. 2004;21:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker C, et al. In vivo imaging of colitis and colon cancer development in mice using high resolution chromoendoscopy. Gut. 2005;54:950–954. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.061283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seno H, et al. Efficient colonic mucosal wound repair requires Trem2 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:256–261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803343106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.